Abstract

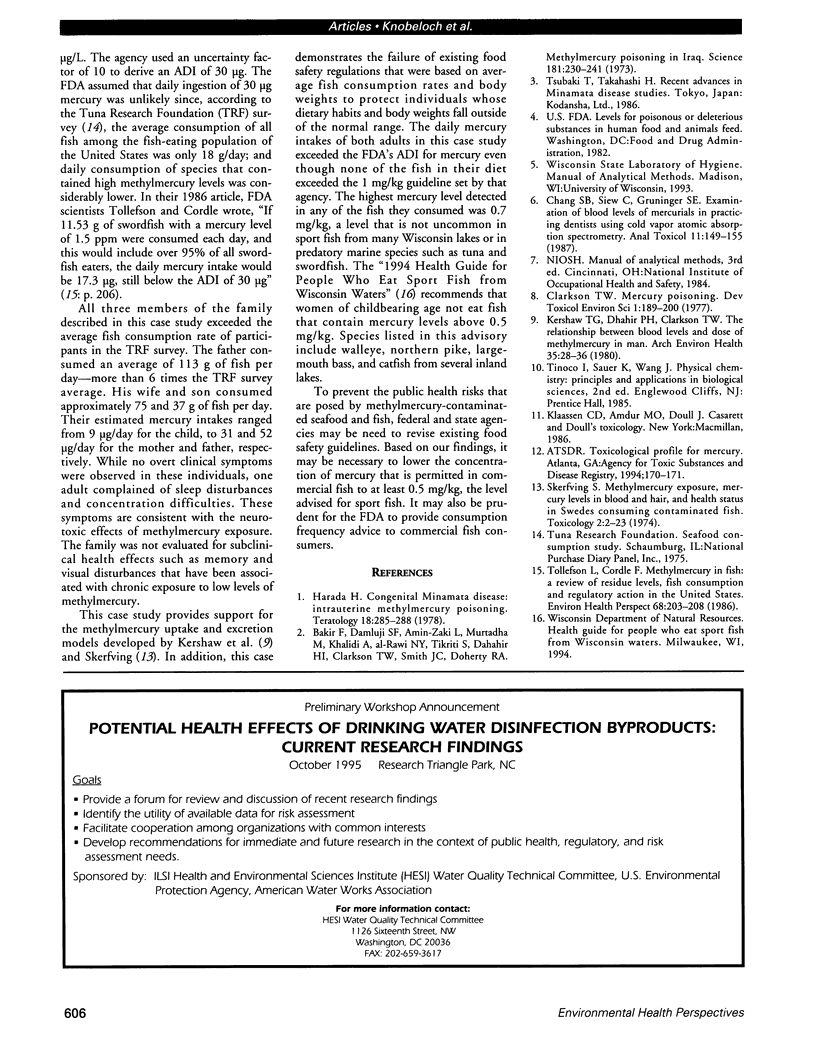

The Wisconsin Division of Health investigated mercury exposure in a 40-year-old man, his 42-year-old wife, and their 2.5-year-old son. At the time of our investigation, these individuals had blood mercury levels ranging from 37 to 58 micrograms/L (normal < 5 micrograms/L) and hair samples from the adults contained 10-12 micrograms mercury/g dry weight. A personal interview and home inspection failed to identify any occupational or household sources of mercury exposure. The family's diet included three to four fish meals per week. The fish was purchased from a local market and included Lake Superior whitefish, Lake Superior trout, farm-raised trout and salmon, and imported seabass. Analysis of these fish found that only one species, the imported seabass, contained significant mercury levels. Two samples of the seabass obtained from the vendor on different days contained mercury concentrations of 0.5 and 0.7 mg/kg. Based on consumption estimates, the average daily mercury intakes for these individuals ranged from 0.5 to 0.8 micrograms/kg body weight. Six months after the family stopped consuming the seabass, blood mercury levels in this man and woman were 5 and 3 micrograms/L, respectively. Analysis of sequential blood samples confirmed that mercury elimination followed first-order kinetics with a half-life of approximately 60 days.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bakir F., Damluji S. F., Amin-Zaki L., Murtadha M., Khalidi A., al-Rawi N. Y., Tikriti S., Dahahir H. I., Clarkson T. W., Smith J. C. Methylmercury poisoning in Iraq. Science. 1973 Jul 20;181(4096):230–241. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. B., Siew C., Gruninger S. E. Examination of blood levels of mercurials in practicing dentists using cold-vapor atomic absorption spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 1987 Jul-Aug;11(4):149–153. doi: 10.1093/jat/11.4.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M. Congenital Minamata disease: intrauterine methylmercury poisoning. Teratology. 1978 Oct;18(2):285–288. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420180216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw T. G., Clarkson T. W., Dhahir P. H. The relationship between blood levels and dose of methylmercury in man. Arch Environ Health. 1980 Jan-Feb;35(1):28–36. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1980.10667458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerfving S. Methylmercury exposure, mercury levels in blood and hair, and health status in Swedes consuming contaminated fish. Toxicology. 1974 Mar;2(1):3–23. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(74)90038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson L., Cordle F. Methylmercury in fish: a review of residue levels, fish consumption and regulatory action in the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 1986 Sep;68:203–208. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8668203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]