Abstract

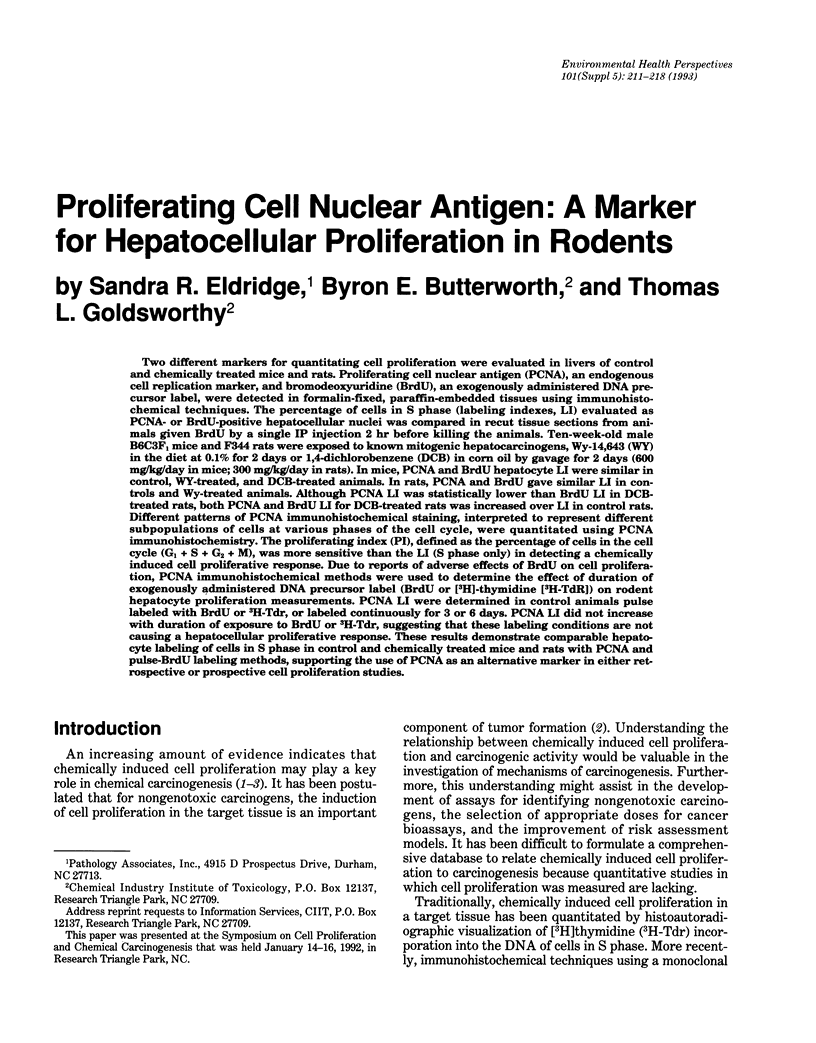

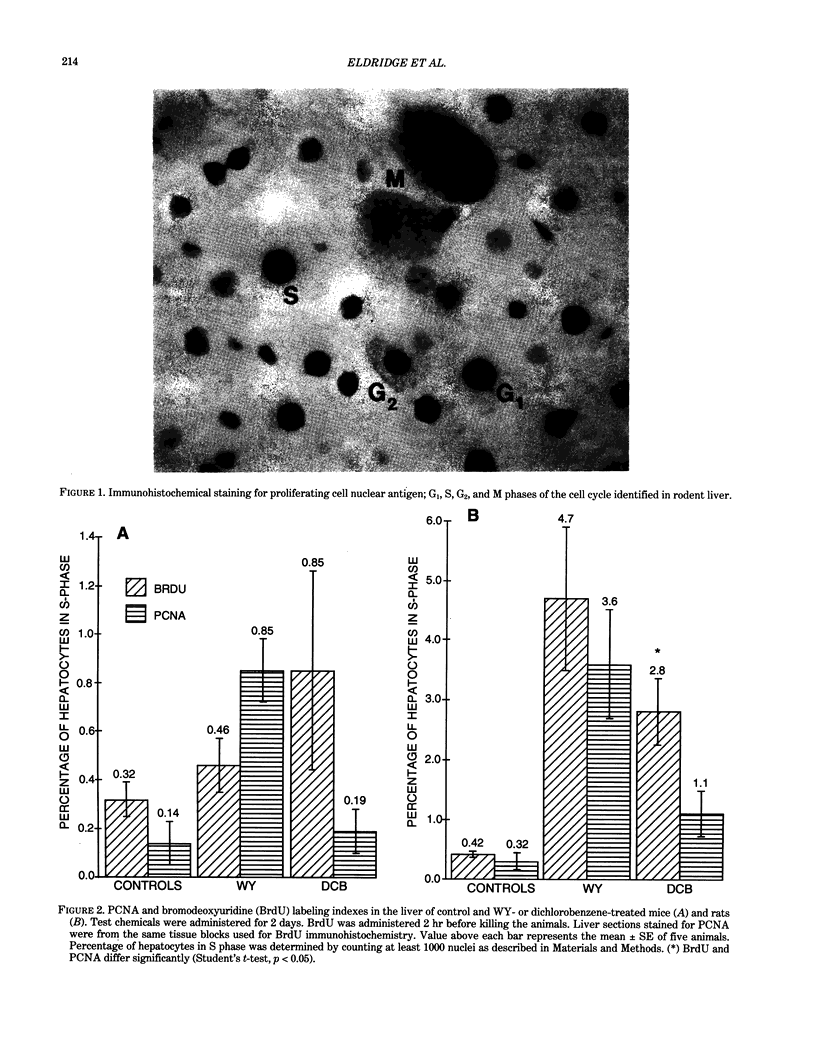

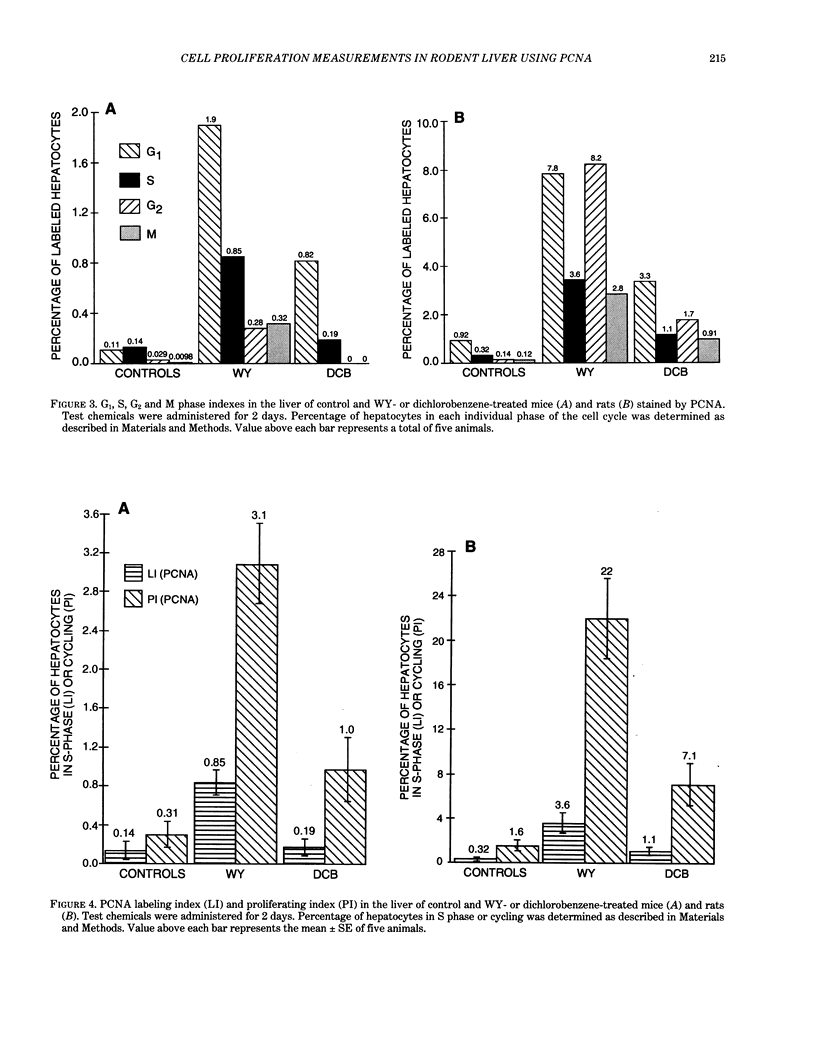

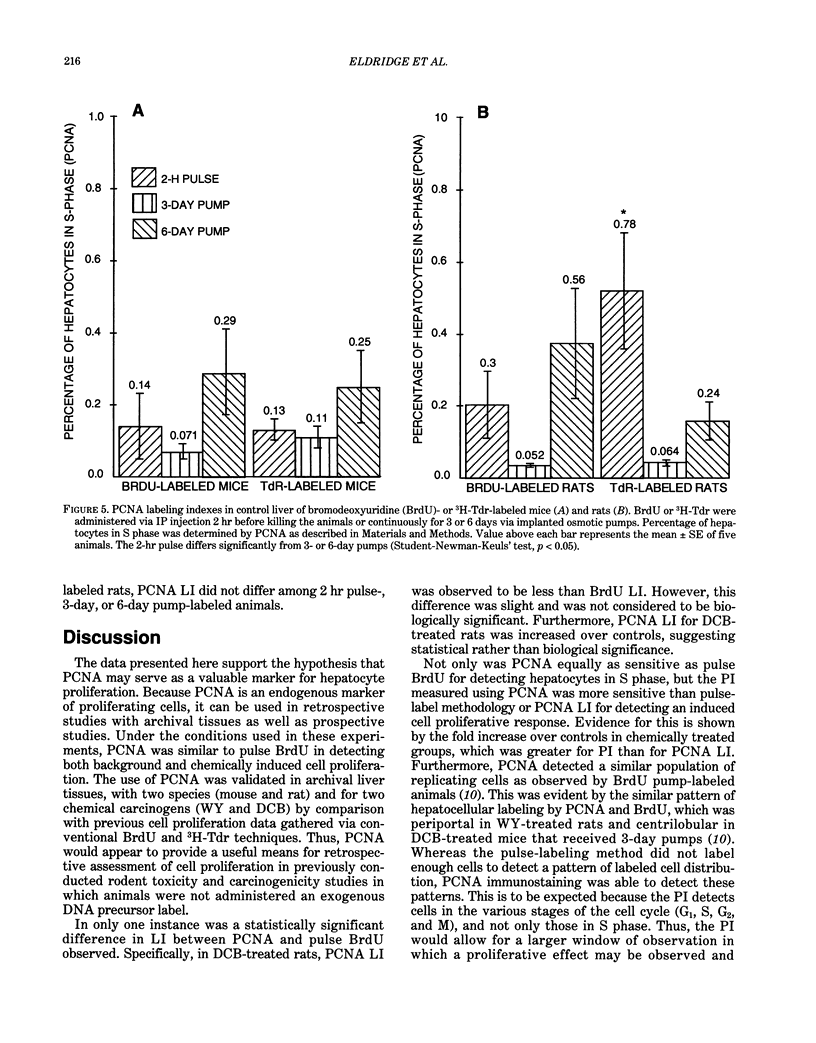

Two different markers for quantitating cell proliferation were evaluated in livers of control and chemically treated mice and rats. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), an endogenous cell replication marker, and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), an exogenously administered DNA precursor label, were detected in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using immunohistochemical techniques. The percentage of cells in S phase (labeling indexes, LI) evaluated as PCNA- or BrdU-positive hepatocellular nuclei was compared in recut tissue sections from animals given BrdU by a single IP injection 2 hr before killing the animals. Ten-week-old male B6C3F1 mice and F344 rats were exposed to known mitogenic hepatocarcinogens, Wy-14,643 (WY) in the diet at 0.1% for 2 days or 1,4-dichlorobenzene (DCB) in corn oil by gavage for 2 days (600 mg/kg/day in mice; 300 mg/kg/day in rats). In mice, PCNA and BrdU hepatocyte LI were similar in control, WY-treated, and DCB-treated animals. In rats, PCNA and BrdU gave similar LI in controls and Wy-treated animals. Although PCNA LI was statistically lower than BrdU LI in DCB-treated rats, both PCNA and BrdU LI for DCB-treated rats was increased over LI in control rats. Different patterns of PCNA immunohistochemical staining, interpreted to represent different subpopulations of cells at various phases of the cell cycle, were quantitated using PCNA immunohistochemistry. The proliferating index (PI), defined as the percentage of cells in the cell cycle (G1 + S + G2 + M), was more sensitive than the LI (S phase only) in detecting a chemically induced cell proliferative response.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baserga R. Growth regulation of the PCNA gene. J Cell Sci. 1991 Apr;98(Pt 4):433–436. doi: 10.1242/jcs.98.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo R., Frank R., Blundell P. A., Macdonald-Bravo H. Cyclin/PCNA is the auxiliary protein of DNA polymerase-delta. Nature. 1987 Apr 2;326(6112):515–517. doi: 10.1038/326515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth B. E. Consideration of both genotoxic and nongenotoxic mechanisms in predicting carcinogenic potential. Mutat Res. 1990 Sep;239(2):117–132. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(90)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celis J. E., Celis A. Cell cycle-dependent variations in the distribution of the nuclear protein cyclin proliferating cell nuclear antigen in cultured cells: subdivision of S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 May;82(10):3262–3266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltrera M. D., Gown A. M. PCNA/cyclin expression and BrdU uptake define different subpopulations in different cell lines. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991 Jan;39(1):23–30. doi: 10.1177/39.1.1670579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge S. R., Tilbury L. F., Goldsworthy T. L., Butterworth B. E. Measurement of chemically induced cell proliferation in rodent liver and kidney: a comparison of 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine and [3H]thymidine administered by injection or osmotic pump. Carcinogenesis. 1990 Dec;11(12):2245–2251. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.12.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galand P., Degraef C. Cyclin/PCNA immunostaining as an alternative to tritiated thymidine pulse labelling for marking S phase cells in paraffin sections from animal and human tissues. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1989 Sep;22(5):383–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1989.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia R. L., Coltrera M. D., Gown A. M. Analysis of proliferative grade using anti-PCNA/cyclin monoclonal antibodies in fixed, embedded tissues. Comparison with flow cytometric analysis. Am J Pathol. 1989 Apr;134(4):733–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwell A., Foley J. F., Maronpot R. R. An enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining of proliferating cell nuclear antigen in archival rodent tissues. Cancer Lett. 1991 Sep;59(3):251–256. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(91)90149-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurki P., Vanderlaan M., Dolbeare F., Gray J., Tan E. M. Expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)/cyclin during the cell cycle. Exp Cell Res. 1986 Sep;166(1):209–219. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier T. L., Berger E. K., Eacho P. I. Comparison of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine and [3H]thymidine for studies of hepatocellular proliferation in rodents. Carcinogenesis. 1989 Jul;10(7):1341–1343. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.7.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R. J., Hall P. A., Haldane J. S., van Noorden S., Price Y., Lane D. P., Wright N. A. A comparison of immunohistochemical markers of cell proliferation with experimentally determined growth fraction. J Pathol. 1991 Oct;165(2):173–178. doi: 10.1002/path.1711650213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S. R., Key M. E., Kalra K. L. Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991 Jun;39(6):741–748. doi: 10.1177/39.6.1709656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weghorst C. M., Henneman J. R., Ward J. M. Dose response of hepatic and renal DNA synthetic rates to continuous exposure of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) via slow-release pellets or osmotic minipumps in male B6C3F1 mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991 Feb;39(2):177–184. doi: 10.1177/39.2.1987261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]