Three years ago, when the proportion of medical students making family medicine their first residency choice dropped below 30% for the first time, program directors called it “a blip.”

This year they will have to come up with a new word, because the proportion has dropped to 24%.

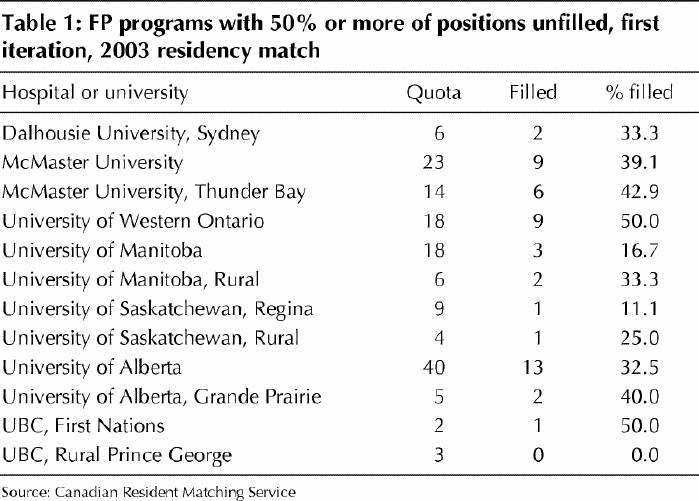

After the first round of the 2003 residency match was completed Feb. 27, 139 of 484 training positions in family medicine — 29% — remained unfilled, with one-third of the 36 programs filling 50% or less of their openings (Table 1). “Family medicine has seen a major drop in popularity,” explained Sandra Banner, executive director of the Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS).

Table 1

Data from the 2003 match tell a depressing tale. For instance, the number of unmatched students — 115 — was 3 times higher than last year, but almost all of the unmatched students were seeking specialty training. And Banner says few of them will seek a family medicine slot in the match's second iteration, since most do not consider family medicine a career option. Many will likely seek specialty training in the US.

As well, even though 114 more students registered with CaRMS for this year's first iteration, the number matched to family medicine actually declined by 35, to 296 students. “There appears to have been a complete disengagement from family medicine,” says Banner.

But not everyone has been disengaged. Danielle Martin, a fourth-year student at the University of Western Ontario and president of the Canadian Federation of Medical Students, matched with the family medicine program at the University of Toronto. “I never wanted anything else,” she says.

Martin says there are many reasons for students' declining interest in family medicine, but the perception that it is less prestigious than other specialties has become a major factor. “It all comes back to the perception that this is not a sexy field,” she says. “Most of my classmates who did rural medicine electives really enjoyed them, but then they went ahead and chose specialties.”

Martin is also concerned about the denigrating comments she has heard about family medicine during medical school. “In my clerkship year, one of my preceptors said I was way too smart to be a family doctor. And you'd hear things like ‘the family doctor screwed up, and then the patient was taken to [see] a real doctor.’ ”

She thinks student debt is also entering the equation when career choices are being made, with high debt loads encouraging students to seek out higher-paying specialties. As well, some are opting for “lifestyle” specialties that offer more regular practice hours and less onerous call duties than family medicine.

Martin says the combination of lower incomes for FPs and the message that family medicine is the least prestigious medical career is a recipe for disaster. “We have to make it affordable for people to make socially responsible choices and, yes, I consider choosing family medicine is socially responsible, because our system depends on it.”

Dr. Calvin Gutkin, CEO at the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), says the college has been developing a response since the problem first appeared about 3 years ago. Attempts so far have included meetings with medical students and a program to bring students to the CFPC's annual meeting. Meetings have also been held with deans of medicine, and in February the college met with government leaders to make them aware of the problem. “We have to act immediately,” Gutkin says. “If we accept 24%, then we're accepting that the whole system has to change. And if we fall further, it will have a significant impact on the population.”

Dr. Claude Renaud, former director of professional affairs at the CFPC, thinks family medicine “is under the gun on all sorts of levels” because of primary care reform.

“Insecurity has been building for 5 or 6 years because of talk about 24/7 coverage and increased roles for nurse practitioners and pharmacists, and I think students have started to view family medicine as less of an important role,” says Renaud, now chief medical officer at the CMA.

He thinks the future of generalists is being threatened by “the glamour of the subspecialties,” and this holds serious implications for a medicare system that relies on a 40–60 split between primary care physicians and specialists. “If we were to lose the balance we have, the system won't function,” he says. “We need the gatekeepers.”

Although most of the 139 vacant positions in family medicine will be filled in the second round of the match, which is open to international medical graduates, Renaud says this year's bleak first-round results should not be ignored by planners. “They show that family medicine is no longer being viewed as an ideal, as it used to be,” he said.

However, the family medicine brain trust can take heart from 2 other specialties that appear to have overcome low popularity. This year all 66 positions in anesthesia were filled in the first round; as recently as 6 years ago, 20% were unfilled.

And obstetrics/gynecology filled 48 of 49 positions, a distinct improvement over 1999, when 12 of 49 slots were unfilled after the first round.

Banner said the 2003 results for these 2 specialties “mark a real turnaround,” which may be attributable to the completion of hospital restructuring in most parts of the country.

“We've done very aggressive promotion this year,” added Andrée Poirier, director of communications with the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. “Our members were present during career nights, and we sent letters to second- and third-year students. I think these proactive measures have helped.”

Gutkin remains optimistic. “I think we can turn it around,” he says. — Patrick Sullivan, CMAJ

Figure. FP-to-be Danielle Martin: “Choosing family medicine is socially responsible.” Photo by: Steve Wharry