Abstract

To optimize antigen delivery by Salmonella vaccine strains, a system for surface display of antigenic determinants was established by using the autotransporter secretion pathway of gram-negative bacteria. A modular system for surface display allowed effective targeting of heterologous antigens or fragments thereof to the bacterial surface by the autotransporter domain of AIDA-I, the Escherichia coli adhesin involved in diffuse adherence. A major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted epitope, comprising amino acids 74 to 86 of the Yersinia enterocolitica heat shock protein Hsp60 (Hsp6074-86), was fused to the AIDA-I autotransporter domain, and the resulting fusion protein was expressed at high levels on the cell surface of E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Colonization studies in mice vaccinated with Salmonella strains expressing AIDA-I fusion proteins demonstrated high genetic stability of the generated vaccine strain in vivo. Furthermore, a pronounced T-cell response against Yersinia Hsp6074-86 was induced in mice vaccinated with a Salmonella vaccine strain expressing the Hsp6074-86-AIDA-I fusion protein. This was shown by monitoring Yersinia Hsp60-stimulated IFN-γ secretion and proliferation of splenic T cells isolated from vaccinated mice. These results demonstrate that the surface display of antigenic determinants by the autotransporter pathway deserves special attention regarding the application in live attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains.

Besides the importance of generating defined attenuating mutations for optimal induction of an immune response by Salmonella vaccine strains (8, 44, 45), the mode of antigen delivery by such vaccine strains has been shown to play a crucial role for effective vaccination. One strategy of antigen expression is the high-level production of recombinant antigens in the cytoplasm of the vaccine strain. This basic approach was successfully improved by the introduction of promoters that are induced upon invasion of the host tissue (3, 17), two-phase antigen expression continuously generating an antigen-expressing subpopulation of the vaccine strains from a nonexpressing population (26), and systems for the stable maintenance of plasmid vectors encoding the heterologous antigens (6, 11, 33). However, conventional antigen expression in the cytoplasm of Salmonella vaccine strains might result in insufficient stimulation of the immune system (15). This phenomenon might be influenced by the intrinsic toxicity or rapid degradation of the candidate antigen or by further factors that remain to be determined. Several novel approaches have been reported to improve antigen delivery by Salmonella vaccine strains. The secretion of antigens by Salmonella vaccine strains via type I and type III secretion systems has been shown to induce protective immune responses against viral and bacterial pathogens in vaccinated animals (15, 41).

The mechanism of protection against a number of gastrointestinal pathogens has been shown to depend on the induction of protective CD4+ T cells (9, 16, 29, 32, 36). For example, peptides that bind to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules conferring at least partial protection have been defined for rotavirus (4) and Yersinia enterocolitica (36). A CD4+-T-cell dependent immune response is primarily induced when exogenous antigens are taken up by antigen-presenting cells, degraded in the phagolysosome and the derived peptide fragments are subsequently presented by MHC class II molecules to naive T cells (reviewed in reference 13). Based on this rationale, we designed an expression system based on the autotransporter concept (21) that allows the display of antigens or antigenic fragments on the surface of Salmonella vaccine strains, which should result in efficient antigen presentation via the MHC class II pathway. Autotransporter proteins are characterized by the feature that a single polypeptide chain is able to provide all functions necessary to translocate a “passenger domain” across the gram-negative cell envelope and to display this domain in a stable manner on the bacterial surface (21, 38). The natural passenger domains of several autotransporter proteins have recently been replaced by heterologous proteins or protein domains, resulting in display of these determinants on the cell surface of gram-negative bacteria (23-25, 30, 42). In the present study we generated a translational fusion of an MHC class II-restricted epitope of the Y. enterocolitica heat shock protein Hsp60 consisting of amino acids 74 to 86 (Hsp6074-86) (36) to the autotransporter domain of the E. coli adhesin involved in diffuse adherence AIDA-I (1). Surface localization of the Hsp6074-86 epitope in a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine strain and the in vivo stability of the generated constructs were analyzed. Furthermore, the cellular immune response of mice was investigated after vaccination with the Salmonella vaccine strain expressing the Hsp6074-86-AIDA-I fusion protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

All bacterial strains employed in the present study are listed in Table 1. For all purposes (except preparation of frozen stocks), the bacteria were grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates or in liquid medium supplemented with ampicillin or carbenicillin (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, Calif.; 100 mg/liter) or thymine (50 mg/liter) when required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Genotype or phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pEGE2 | Addition of Hsp6074-86 amino terminal to HA-CTB-AIDA encoded on pLAT260 | This study |

| pJM7 | Fusion protein of CTB and the autotransporter domain of AIDA-I, constitutive promoter PTK | 30 |

| pKRI22 | Fusion protein encoded on pLAT260 in a thyA stabilized backbone | This study |

| pKRI43 | Fusion protein encoded on pEGE2 in a thyA stabilized backbone | This study |

| pLAT231 | CTB-AIDA, novel unique BglII site | C. T. Lattemann, unpublished results |

| pLAT260 | Addition of the HA amino terminal to CTB-AIDA encoded on pLAT231 | This study |

| pLAT378 | pJM7 derivative containing a functional thyA gene | C. T. Lattemann, unpublished results |

| CREA0293 | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 aroA | E. A. Freissler, unpublished results |

| CREA1323 | CREA0293 thyA | E. A. Freissler, unpublished results |

| JK321 | azi-6 fhuA23 lacY1 leu-6 mtl-1 proC14 purE42 rpsL109 thi-1 trpE38 tsx-67 Δ(ompT-fepC) zih::Tn10 dsbA::Kan | 22 |

Animals.

Six- to eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Harlan Winkelmann, Borchen, Germany) were kept under a 12-h light-dark schedule in an air-conditioned animal facility in individually ventilated cages (Tecniplast) under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Mice were kept on a lattice, and sterile food and water was provided ad libitum.

Construction of an expression vector for surface display.

E. coli JK321 (22) was used for all cloning procedures. A PCR fragment was generated by using pJM7 (Table 1) (30) as the template with primers EF16 and LAT65 encoding the nine amino acid epitope YPYDVPDYA of the hemagglutinin (HA) of the influenza virus (Table 2). The plasmid vector pJM7 encodes a fusion protein of a modified Vibrio cholerae ctxB gene that contains no cysteine residues (30) and the autotransporter domain of AIDA-I (CTB-AIDA) (30), which is transcriptionally controlled by the constitutive promoter PTK (23). With EF16 and LAT65 for PCR with pJM7 as the template, the resulting fragment contains the promoter region of CTB-AIDA and the signal peptide of the ctxB gene that is used to drive secretion of CTB-AIDA into the periplasm, followed by the HA encoding sequence. Immediately upstream of the HA encoding portion, a BglII restriction site permits further insertion of additional antigenic determinants. The EF16/LAT65 PCR fragment was hydrolyzed with the restriction enzymes ClaI and BamHI and inserted into the plasmid pLAT231 (C. T. Lattemann, unpublished data) treated with ClaI and BglII. The plasmid pLAT231 represents a modification of pJM7, containing an additional BglII recognition site introduced into the ctxB gene immediately downstream of the sequence encoding the CTB leader peptide. This unique BglII site permits insertion of heterologous determinants that will be displayed at the N terminus of the mature fusion protein. The resulting plasmid vector, pLAT260, encodes a translational fusion of the HA epitope and CTB-AIDA. Subsequently, a similar PCR fragment was generated from pJM7 with primers EF16 and LAT64 encoding the Hsp6074-86 epitope. This fragment was cleaved with ClaI and BamHI and inserted into pLAT260 treated with ClaI and BglII, resulting in plasmid pEGE2. The vector pEGE2 encodes a translational fusion of the ctxB leader peptide, Hps6074-86, HA, and CTB-AIDA displaying the Hps6074-86 epitope on the N terminus of the mature fusion protein. According to the predicted molecular weight of the mature fusion proteins encoded on pLAT260 and pEGE2, the fusion proteins were termed FP63 and FP64, respectively. In order to stabilize the expression vectors without antibiotic selection and to provide a postsegregational killing signal, the expression cassettes encoded on pLAT260 and pEGE2 were transferred onto the plasmid vector pLAT378 (Lattemann, unpublished), a derivative of pJM7 that carries the thyA gene of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. In a strain devoid of a functional thyA gene, a plasmid-encoded thyA allele functionally complements the thymidylate synthase function and stabilizes expression vectors both in cultivation medium lacking thymine and in vivo (33). A PCR fragment encoding FP63 was amplified from pLAT260 by using the primers KRI64 and KRI65 hydrolyzed with XbaI and NcoI and transferred into pLAT378, yielding pKRI22. To transfer FP64 into the thyA stabilized vector backbone, a ClaI-KpnI restriction fragment of pEGE2 containing the ctxB leader sequence, Hps6074-86, HA, and the ctxB gene, was inserted into the ClaI-KpnI-treated pKRI22, resulting in pKRI43. The genetic integrity of the constructs was verified by dideoxy chain termination sequencing (4baselab GmbH, Reutlingen, Germany).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Features |

|---|---|---|

| EF16 | 5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTATCACGAGGCCCTTTCGT-3′ | Sense |

| KRI64 | 5′-TTTTTTTCTAGATAAGGATGAATTATGATTAAATT-3′ | Sense, XbaI site (italics) |

| KRI65 | 5′-TTTTTTCCATGGTCAGAAGCTGTATTTTATCC-3′ | Antisense, NcoI site (italics) |

| LAT64 | 5′-GATCAGATCTCTCGAGACCCGCAGCGTCGTTCGCTTTAGAGGCAACTTCTTTAACAGGTGTTCCGTGTGCAT-3′ | Antisense, BglII site (italics), Hsp6074-86 (boldface) |

| LAT65 | 5′-GATCGGATCCAGCGTAATCTGGCACGTCGTATGGATAAGATCTAGGTGTTCCGTGTGCAT-3′ | Antisense, BamHI and BglII sites (italics), HA epitope (boldface) |

Protein techniques.

The expression of the AIDA-I fusion proteins was analyzed by the separation of whole-cell lysates or outer membrane fractions of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and, when appropriate, this was followed by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody against the HA epitope conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany) diluted 1:500 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl; pH 7.4) supplemented with 5% skim milk powder. Unbound antibodies were removed by washing with TBS-T (0.05% Tween 20 in TBS), and bound antibodies were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany).

Surface accessibility of Hsp6074-86 to proteases.

Bacteria were collected from agar plates, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), and adjusted to an optical density at 575 nm (OD575) of 10.0 before surface-exposed protein domains were cleaved by incubation of the suspension at 37°C for 10 min with trypsin (50 mg/liter). Trypsin was removed after the reaction by gently washing the cells twice with PBS and then subjected to further manipulations.

Preparation of outer membranes.

Bacterial outer membranes were prepared as described elsewhere (25) with minor modifications. Briefly, bacteria grown overnight were harvested from agar plates and resuspended in PBS as described above. The suspension was sonicated on ice with 30 pulses (1 s each) at maximum intensity (Branson Ultrasonics Corp., Danbury, Conn.) to lyse the cells. Debris was removed from the lysate by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min. l-Laurylsarcosinate (1% [vol/vol]) was added to the cleared solution to solubilize the inner membrane. Subsequently, the outer membrane was separated from the cytoplasm and inner membrane by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

For indirect immunofluorescence, overnight bacterial cultures were harvested from agar plates, resuspended in PBS, and fixed on coverslips with paraformaldehyde (2.5%) for 20 min. Blocking was performed for 10 min in PBS containing 1% fetal calf serum (FCS). The coverslips were washed twice in 500 μl of PBS and incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against HA (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.; 1:500 in PBS containing 1% FCS) for 1 h. Unbound antibodies were removed by three washes with 500 μl of PBS for 10 min each, and the detection of surface-bound antibodies was carried out by incubation with a Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody. The coverslips were washed again three times for 10 min with 500 μl of PBS, and the labeled bacteria were visualized by oil immersion fluorescence microscopy at an excitation wavelength of 540 nm.

Preparation of freeze stocks.

To ensure reproducibility between different immunization experiments, frozen inocula of the vaccine strains were prepared as suggested by Igwe et al. (18) for Y. enterocolitica. Briefly, a single colony of Salmonella from LB agar was resuspended in cultivation medium (LB medium plus 50 μg of carbenicillin/ml), and 10-fold serial dilutions were subsequently prepared and incubated overnight at 27°C with shaking (200 rpm). A culture with an OD600 of ca. 0.5 was diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 and incubated until an OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0 was attained. The bacteria were harvested, resuspended in LB medium-10% glycerol, and stored at −80°C. The quality of each batch was controlled by comparing the viable cell count of an aliquot before and after freezing; the count was determined to be at least 90% in each case.

Immunization experiments.

Prior to oral immunization the mice were left for 12 to 18 h without food and water. Salmonella stocks were thawed prior to use, washed three times with PBS, and diluted to a concentration of 5 × 1010 CFU/ml. Doses were confirmed by plating of serial dilutions of frozen stocks. Then, 1010 CFU bacteria in 200 μl of PBS or 200 μl of PBS alone was applied intragastrically by using Minnesota olive-tipped feline catheters (Eickemeyer, Tuttlingen, Germany). Water and food were returned 2 h after immunization. For all studies, mice were immunized once. Salmonella stocks were diluted to a concentration of 5 × 106 CFU/ml of PBS for intravenous immunization. The tail veins of the mice were dilated by irradiation with red light, and 200 μl of the bacterial suspension was injected into the vein by using a 0.4-by-20-mm syringe.

In vivo colonization and stability tests.

Seven days after immunization the mice were sacrificed and the respective organs were removed. The organs were homogenized in sterile PBS with 0.5% (vol/vol) Tergitol (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) and 0.5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) by using Tenbroeck homogenizers (Wheaton Science Products). The number of viable bacteria present in the organs was determined by counting serial dilutions on LB agar plates with or without carbenicillin (50 μg/ml) antibiotic selection.

T-cell assays.

All cell cultures were carried out in Click-RPMI 1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 100 U of penicillin/ml, 10 μg of streptomycin/ml, 10 mM HEPES, 7.5% sodium bicarbonate, 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% (vol/vol) nonessential amino acids, and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (all materials were from Biochrom, Berlin, Germany). Mice were sacrificed and splenectomized 21 days after immunization. Single cell suspensions were prepared from pooled spleens of four mice from each group by passing them through a steel mesh. Erythrocytes were lysed by incubation in 0.15 M NH4Cl solution (pH 7.2), and mononuclear cells were enriched by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 20 min in Ficoll 1:1 (density, 1.077:1.090; Biochrom, Berlin, Germany). B cells were eliminated by performing two subsequent 30-min incubation steps on petri dishes coated with 1,000 μg of goat anti-rat IgG (Dako). The nonadherent cell fraction contained ca. 70% CD3+ T cells. Enriched splenic T cells (5 × 104 per well) were cultured in the presence of 2 × 105 mitomycin C (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)-treated splenic mononuclear cells and antigen in 0.2 ml of cell culture medium in round-bottom 96-well microculture plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany). The Y. enterocolitca Hsp6074-86-peptide antigen and the ovalbumin-peptide antigen Ova323-339 (both synthesized by D. Palm, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany) were used at concentrations of 10 μg/ml. Controls included cells that were stimulated with medium, concanavalin A (3 μg/ml; Amersham Pharmacia), or Ova323-339 as an irrelevant peptide. T-cell proliferation was measured by incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) or [3H]thymidine (ICN). Cultures were pulsed with BrdU during the final 16 h of a 3-day culture, and the incorporation of BrdU was measured by using a cell proliferation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the manufacturer's intructions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). Alternatively, cells were pulsed during the final 16 h of a 3-day culture with 18.5 kBq of [3H]thymidine per well. Cultures were harvested by using an automatic cell-harvester (Packard, Meriden, Conn.), and radioactivity was counted in a β-counter (Packard). Proliferative responses were expressed as stimulation indexes (SI) calculated as follows: SI = [3H]thymidine uptake (counts per minute) in the presence of the indicated antigen/[3H]thymidine uptake (counts per minute) without antigen.

Cytokine ELISA.

ELISA plates (Greiner, Nürtingen, Germany) were incubated at 4°C overnight with 0.5 μg of AN-18.17.24 monoclonal antibody for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or the monoclonal antibody 11B11 for interleukin-4 (IL-4) in 50 μl of PBS per well. Plates were washed, blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at 37°C, washed, and incubated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of test solution per well. The following day, the plates were incubated with 0.1 μg of the monoclonal antibody R4-6A2 for IFN-γ or antibody 24G2 for IL-4 in 50 μl of PBS per well for 1 h at 37°C. After a further washing, plates were incubated with a streptavidin-biotin alkaline phosphatase-conjugate solution (Dako) for 60 min at 37°C, washed, and developed with a p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution (Sigma). The plates were read with a Sunrise ELISA reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 405 nm (reference at 490 nm). Known concentrations of IL-4 and IFN-γ were included as positive controls to determine the amount of cytokines secreted by the restimulated T cells.

Statistical analysis.

Paired and unpaired two-tailed Student t tests were used to determine the statistical significance. The level of significance was set at 0.001.

RESULTS

Construction of Salmonella vaccine strains displaying antigenic determinants on the cell surfaces.

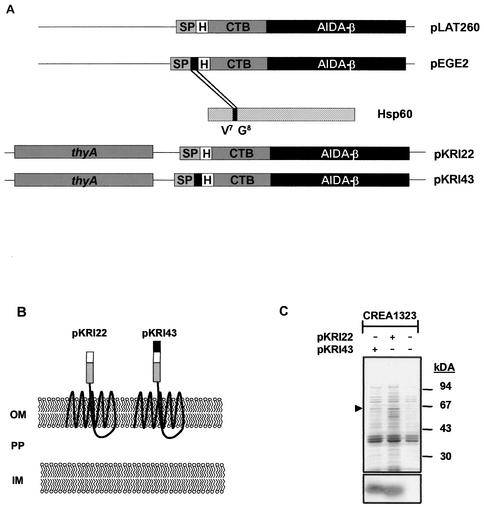

The autotransporter secretion pathway of gram-negative bacteria was employed to direct the MHC class II restricted epitope Hsp6074-86 of the Y. enterocolitica heat shock protein 60 to the surface of Salmonella vaccine strains. The autotransporter domain of the AIDA-I adhesin has been shown to efficiently target heterologous passenger domains, such as defined epitopes, CTB, and β-lactamase, to the surfaces of E. coli cells (24, 25, 30). A series of plasmid vectors was generated as described in Materials and Methods to target antigenic determinants to the surface of Salmonella vaccine strains so that the heterologous antigenic determinant would be surface displayed at the N terminus of a respective translational fusion to CTB-AIDA. To improve the accessibility of the antigenic epitope to phagolysosomal proteases, CTB was kept as a spacer element in between the autotransporter domain and the epitope. Expression of CTB-AIDA fusion protein is controlled at the transcriptional level by the constitutive promoter PTK (23). Plasmid vector pLAT260 encodes a translational fusion of the HA epitope to CTB-AIDA, whereas pEGE2 encodes a translational fusion of the Hsp6074-86 epitope to HA-CTB-AIDA (Fig. 1A). According to the predicted molecular weight, the HA-CTB-AIDA fusion was termed FP63, and the fusion protein of Hsp6074-86 to HA-CTB-AIDA was termed FP64. To guarantee genetic stability of the Salmonella vaccine strain, DNA fragments encoding both fusion proteins encoded on pLAT260 and pEGE2 were transferred into a plasmid vector backbone carrying a thyA allele of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, yielding pKRI22 and pKRI43, respectively. For vaccination purposes, pKRI22 and pKRI43 were introduced into the aroA-attenuated live vaccine strain S. enterica serovar Typhimurium CREA1323 carrying an inactivated thyA allele (E. Freissler, unpublished data). The thyA allele encoded on pKRI22 and pKRI43 functionally complements the inactivated thyA gene present in CREA1323, resulting in an efficient stabilization of the vaccine strain due to postsegregational killing of plasmidless bacteria (data not shown). Figure 1A schematically illustrates the constructed plasmid vectors, and Fig. 1B depicts the putative membrane phenotypes of the vaccine strains conferred by the corresponding plasmids according to the study by Maurer et al. (30).

FIG. 1.

Construction of a vector for surface display of antigenic determinants in Salmonella vaccine strains. (A) Schematic illustration of generated plasmid vectors. (B) Proposed membrane phenotype conferred by generated constructs. CP, cytoplasm; IM, inner membrane; PP, periplasm; OM, outer membrane. (C) Membrane preparations of Salmonella vaccine strains expressing AIDA fusion proteins FP63 and FP64 (arrowhead) analyzed by Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE (upper panel) and immunoblotting, including a monoclonal antibody against the HA tag (lower panel).

FP63 and FP64 were found to be strongly expressed in E. coli JK321 transformed with the respective plasmid vectors migrating to 63 and 64 kDa (data not shown). To demonstrate outer membrane targeting of both fusion proteins in the Salmonella vaccine strain CREA1323, outer membranes were prepared from CREA1323(pKRI22) and CREA1323(pKRI43) (Fig. 1C). FP63 and FP64 represent highly abundant proteins in the outer membrane fractions of CREA1323(pKRI22) and CREA1323(pKRI43), respectively, as assessed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C, upper panel) and Western blot with a specific monoclonal antibody against the HA tag (Fig. 1C, lower panel), demonstrating efficient outer membrane targeting of the respective fusion proteins in these strains.

Surface localization of FP63 and FP64.

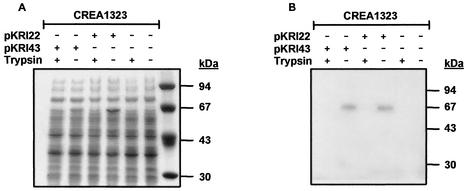

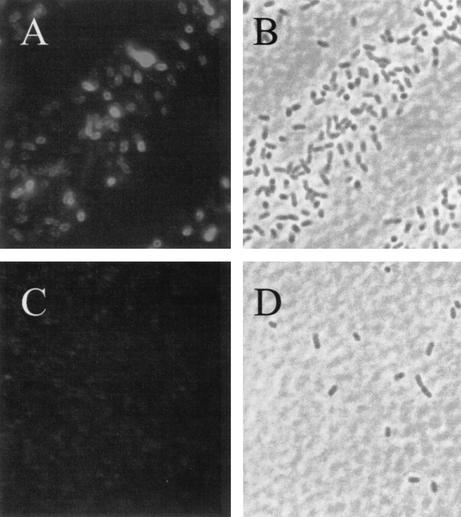

Monitoring of surface localization of FP63 and FP64 in CREA1323(pKR22) and CREA1323(pKRI43) was achieved by the treatment of viable, physiologically intact cells with trypsin. This treatment selectively removes surface-exposed protein domains, while not affecting cytoplasmic and periplasmic proteins or proteins embedded in the outer membrane that do not expose protease-sensitive structures, thus allowing to discriminate between surface and cytoplasmic or periplasmic localization of passenger domains fused to autotransporters (25, 31). Whole-cell lysates derived from overnight plate cultures of CREA1323(pKR22) and CREA1323(pKRI43) treated with or without trypsin were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. FP63 and FP64 are expressed efficiently in CREA1323 as visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (Fig. 2A) and immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2B) of SDS-PAGE-separated cell lysates of the corresponding strains. In addition, trypsin treatment of physiolgically intact CREA1323(pKR22) and CREA1323(pKRI43) led to the disappearance of FP63 and FP64 (Fig. 2), confirming surface exposure of the Hsp6074-86 epitope in CREA1323(pKRI43). Surface exposure of FP64 was further confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 3). The HA specific monoclonal antibody bound selectively to CREA1323(pKRI43) cells expressing FP64 but did not label the plasmidless parent strain.

FIG. 2.

Expression and surface accessibility of AIDA-I fusion proteins to exogenous proteases. The Salmonella vaccine strain CREA1323 was transformed with pKRI22 and pKRI43 encoding the AIDA-I fusion proteins FP63 and FP64, respectively. Expression and surface localization of FP63 and FP64 (arrowheads) in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium CREA1323 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (A) and immunoblotting with an monoclonal antibody against the HA tag (B). Surface accessibility was monitored by tryptic digestion of viable physiologically intact cells as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 3.

Surface exposure of FP64 in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine strain CREA1323(pKRI43). Indirect immunofluorescence of Salmonella strains CREA1323(pKRI43) (A and B) and CREA1323 (C and D). Physiologically intact bacteria were labeled with a monoclonal antibody against the HA epitope and a Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Labeled bacteria were visualized by fluorescence microscopy (A and C) or transmission light microscopy (B and D).

Stability of FP63- and FP64-expressing vaccine strains in vivo.

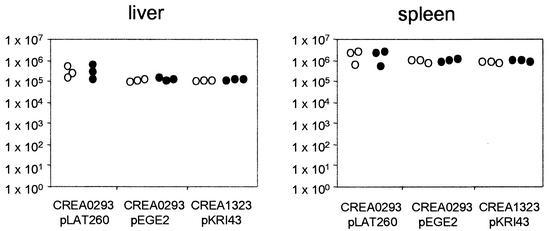

Mice were immunized intravenously with 5 × 106 CFU CREA0293(pLAT260), CREA0293(pEGE2), or CREA1323(pKRI43), and the persistence of the vaccine strains was determined 7 days postimmunization (dpi) in the spleens and livers of the immunized animals by agar plating homogenized suspensions of these organs. The stability of the heterologous plasmid vectors was determined by cultivation of isolated bacteria on selective and nonselective agar plates. A difference in the ability to grow on antibiotic-selective agar compared with growth on antibiotic-free agar served as a measure for the stability of the plasmids that coded for the AIDA fusion proteins. Figure 4 shows that for all vaccine strains the mice showed a pronounced colonization, and all expression vectors were propagated in a stable manner, regardless of whether the postsegregational killing system was present. The mean plasmid carriage rates in the spleen were 98, 109, and 116% for pLAT260, pEGE2, and pKRI43, respectively. Likewise, the mean rates in the liver were 108, 106, and 109%, respectively. No significant differences between the carriage rates of the different strains were observed. There were also no significant differences between the CFU of bacteria recovered from the organs when we compared different strains or when we compared carbenicillin-resistant or -sensitive CFU of the same strain. Notably, CREA0293(pEGE2) and CREA1323(pKRI43) expressing FP64 showed the same colonization efficacy and genetic stability, indicating that (i) the thyA system does not interfere with the colonization properties of the vaccine strain and (ii) the AIDA autotransporter system does not represent a selective disadvantage for bacterial cells bearing plasmids encoding such fusion proteins.

FIG. 4.

Persistence and genetic stability of Salmonella vaccine strains expressing AIDA fusion proteins in vivo. Groups of three C57BL/6 mice were immunized intravenously with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium CREA0293(pLAT260), CREA0293(pEGE2), or CREA1323(pKRI43). The mice were sacrificed 7 dpi, and bacterial numbers present in the spleen and liver of each animal were determined by plating of the homogenized organs on LB agar alone (○) or on LB agar containing carbenicillin (•).

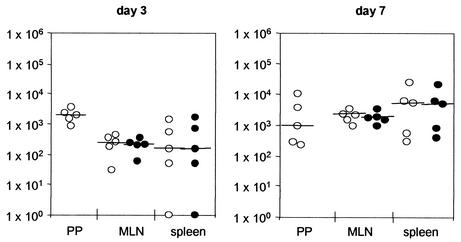

Stability of CREA0293(pEGE2) was also monitored by using an oral immunization regimen analyzing colonization and genetic stability 3 and 7 dpi in Peyer's patches (PP), mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), and spleens (Fig. 5). Bacteria colonized mice after oral immunization and showed a genetic stability that was as high as that following intravenous immunization. The mean carriage rates on day 3 were 106 and 79% in the MLN and spleens, respectively. Likewise on day 7, the rates were 109 and 92%, respectively. The determination of exact carriage rates in the spleen on day 3 was difficult due to the low numbers of CFU recovered. There were no significant differences between the CFU counted on carbenicillin-containing plates and antibiotic-free plates. Furthermore, the genetic stability was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis, demonstrating correct expression of FP64 in five randomly selected clones from a nonselective plate after recovery from the spleens of vaccinated animals (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Persistence and genetic stability of Salmonella vaccine strains expressing AIDA fusion proteins in orally immunized mice. C57BL/6 mice were immunized orally with 1010 CFU of CREA0293(pEGE2). At 3 and 7 dpi, colonization and genetic stability of the vaccine strain in Peyer's patches (PP), MLN, and spleens were assessed by plating homogenized organs on selective (○) and nonselective (•) media.

CREA1323(pKRI43) expressing surface-displayed Hsp6074-86 induces an antigen-specific immune response in vaccinated animals.

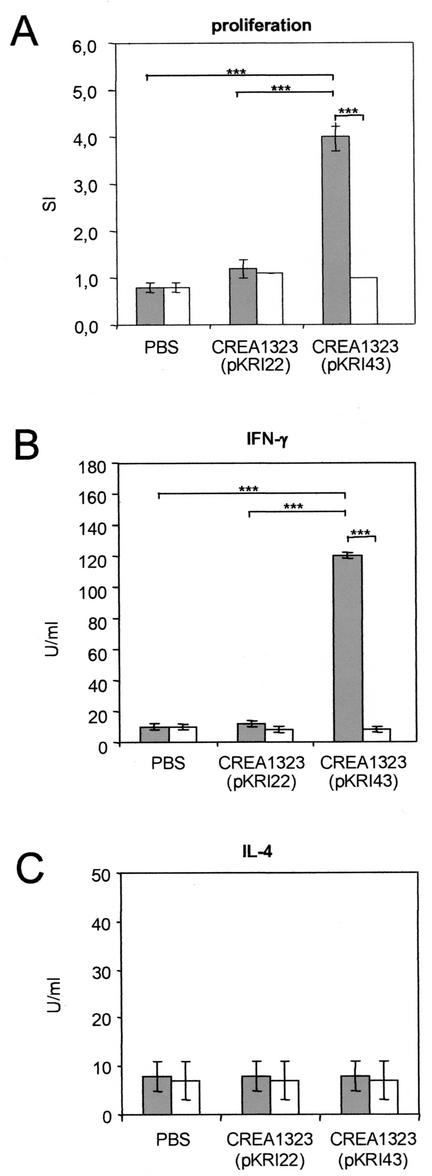

Although high genetic stability of AIDA fusion proteins was demonstrated independently of the presence of the thyA stabilization system, the strains CREA1323(pKRI22) and CREA1323(pKRI43) bearing the stabilization system were selected for vaccination experiments. C57BL/6 mice were immunized orally with 1010 CFU of CREA1323(pKR22) or CREA1323(pKR43), and the cellular immune response was determined 21 dpi. Splenic T cells were isolated and investigated for epitope-specific proliferation in the presence of mitomycin C-treated antigen-presenting cells and Hsp6074-86-peptide as a test antigen or Ova323-339 as a negative control. Vaccination of mice with CREA1323(pKRI43) resulted in specific proliferation of the isolated T cells in response to Hsp6074-86 (Fig. 6A). No proliferation was observed in the presence of the irrelevant Ova223-339 peptide or in control animals vaccinated with CREA1323(pKRI22) or treated with PBS. To analyze the type of immune response in more depth, IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion of restimulated T cells was monitored (Fig. 6B and C). In the presence of the Hsp6074-86 peptide, the T cells isolated from CREA1323(pKRI43)-vaccinated mice secreted high amounts of IFN-γ. In contrast, no IFN-γ secretion was observed in control groups or in the presence of Ova223-339. Furthermore, IL-4 secretion could not be demonstrated in any group, indicating a bias of the Hsp6074-86-specific immune reponse toward the Th1 type.

FIG. 6.

Antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production of restimulated T cells isolated from mice immunized with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain expressing AIDA-I fusion proteins. Groups of four C57BL/6 mice were immunized orally with 1010 CFU of the Salmonella vaccine strains CREA1323(pKRI22) and CREA1323(pKRI42) or with PBS. Splenocytes were harvested 21 dpi and pooled for each group. T cells were enriched by panning by using goat anti-rat IgG-coated petri dishes and restimulated in vitro for 3 days with 10 μg of either Y. enterocolitica Hsp6074-86 peptide ( ) or the unrelated ovalbumin-peptide Ova323-339 (□)/ml. (A) Antigen-specific proliferation was measured by calculating the SI. IFN-γ secretion (B) and IL-4 secretion (C) were measured by a cytokine-specific capture ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. The bars represent the means of quadruplicate wells, and error bars represent the standard deviation. The results are representative of three independent experiments. The differences between the values obtained from the vaccine group and those obtained from the control groups were statistically highly significant at P < 0.001) (✽✽✽) for the proliferation and the IFN-γ assays.

DISCUSSION

We have successfully engineered the autotransporter pathway of gram-negative bacteria to display antigenic peptides on the cell surface of a Salmonella vaccine strain. The Y. enterocolitica Hsp6074-86 epitope was translocated as part of a tripartite fusion to CTB and the AIDA-I autotransporter domain across the cell envelope of the Salmonella vaccine strain CREA1323 and presented in a stable manner on the cell surface. The AIDA-I fusion proteins FP63 and FP64 were expressed efficiently in CREA1323 and were found to localize in the outer leaflet of the outer membrane, exposing the antigenic peptide to the environment. Our approach has been designed for the delivery of MHC class II-restricted epitopes by live attenuated vaccine strains. Indeed, antigen-specific proliferation of T cells isolated from mice vaccinated with CREA1323(pKRI43) expressing the Y. enterocolitica Hsp6074-86 peptide as part of a tripartite fusion with CTB and the AIDA-I autotransporter was demonstrated. The observed T-cell proliferation was accompanied by high-level IFN-γ secretion, illustrating an effective immune stimulation by the vaccine strain. No antigen-specific secretion of IL-4 was detected. This indicates a bias of the antigen-specific immune response toward the Th1 type and is in accordance with results obtained with attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains harboring a mutation in the aroA gene (8, 46). Furthermore, preliminary immunization experiments indicate that the Hsp6074-86-specific IFN-γ secretion could be augmented by a booster immunization at day 21 and isolation of splenic T cells 35 dpi. Since antigen processing for MHC class I pathway by antigen-presenting cells infected with Salmonella strains has been demonstrated (37), it is tempting to speculate that an efficient cytotoxic immune response might also be induced by surface-displayed antigens.

Foreign genetic elements encoding heterologous proteins represent a metabolic burden for the vaccine strain, often resulting in further attenuation of the strain or in downregulation of antigen expression and suboptimal antigen delivery (reviewed by Galen and Levine [10]). This is exemplified by the rapid loss of expression vectors in Salmonella vaccine strains devoid of genetic stabilization systems when heterologous antigens at high levels or toxic antigens are expressed. It is noteworthy that the AIDA autotransporter system presented here displays a high degree of intrinsic genetic stability. Independent of the presence of the thyA system providing postsegregational killing, nearly 100% of the reisolated bacteria propagated the expression vector. Thus, the presence of high levels of the AIDA autotransporter domain in the outer membrane is apparently well tolerated by the vaccine strain and does not impose a selective pressure on plasmid-bearing cells.

Our data are supported by the recent report of Ruiz-Perez et al. (39), who demonstrated the induction of a strong humoral immune response in mice immunized with a Salmonella vaccine strain expressing an immunodominant epitope of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein displayed by the Salmonella MisL autotransporter. This system requires multiple immunizations due to the instability of the plasmid vector, as indicated by the necessity for the addition of ampicillin to the drinking water of immunized mice to avoid plasmid loss in vivo by the vaccine strain (39). Thus, it might be crucial to balance a high level of antigen expression with a well-tolerated level for the bacteria in order to achieve optimal antigen delivery.

Further systems for surface display of antigenic determinants in Salmonella vaccine strains comprise the insertion of heterologous antigenic peptides into the hypervariable region of FliC, the main flagellar component (35), or surface-exposed loops of outer membrane proteins such as the E. coli proteins LamB (2) or PhoE (43). However, drawbacks of these systems include the constrained conformation and the size limitation of the heterologous insert (5). The insertion of heterologous epitopes into surface-exposed loops of PhoE has been reported to be influenced by the importance of flanking amino acid residues on the processing of the fusion protein (20). A large number of promising results with intravenous or parenteral immunization protocols have been obtained; however, oral immunization regimens for Salmonella vaccine strains expressing such fusion proteins remain to be optimized (7, 14, 19, 27, 34). Recently, surface display of a translational fusion of a part of the hepatitis B virus surface antigen and the ice nucleating protein of Pseudomonas syringae (lnp) has been reported in the S. enterica serovar Typhi vaccine strain Ty21a (28). In vaccinated mice, antibody responses against the insert peptide were demonstrated after the cultivation of the vaccine strain at a temperature of 25°C prior to immunization.

Several other approaches to optimize antigen delivery by Salmonella vaccine strains based on the manipulation of bacterial secretion systems have been reported (10, 15, 41). These systems provide means to secrete antigens into the surrounding environment (10, 15) or to translocate the antigenic fusion protein into the cytoplasm of host cells (41). The E. coli alpha-hemolysin pathway has primarily been employed for the secretion of full-length antigens by Salmonella vaccine strains and has demonstrated its efficacy in several animal models of infectious diseases (12). These include the type III secretion system located in the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, which has successfully been employed for the delivery of MHC class I-restricted epitopes (41). Interestingly, this type III secretion system shows some degree of promiscuousness allowing the translocation of large antigen fragments fused to the amino terminus of YopE, a secreted virulence factor of Y. enterocolitica (40).

In conclusion, surface display of antigenic determinants by autotransporter proteins has been demonstrated to be an effective approach for antigen delivery by Salmonella vaccine strains, eliciting strong humoral (39) and Th1-biased MHC class II-restricted cellular immune responses (the present study) in vaccinated animals and thus merits further investigation to improve surface display with respect to the expression of full-length antigens or MHC class I-restricted epitopes.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Gerland for excellent technical assistance and J. Maurer and E. A. Freissler for expertise with the thyA system. We are grateful to P. Kyme for revising the manuscript.

U.K. and K.R. contributed equally to this study.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Benz, I., and M. A. Schmidt. 1989. Cloning and expression of an adhesin (AIDA-I) involved in diffuse adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 57:1506-1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charbit, A., A. Molla, W. Saurin, and M. Hofnung. 1988. Versatility of a vector for expressing foreign polypeptides at the surface of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70:181-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatfield, S. N., I. G. Charles, A. J. Makoff, M. D. Oxer, G. Dougan, D. Pickard, D. Slater, and N. F. Fairweather. 1992. Use of the nirB promoter to direct the stable expression of heterologous antigens in Salmonella oral vaccine strains: development of a single-dose oral tetanus vaccine. Bio/Technology 10:888-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi, A. H., M. Basu, M. M. McNeal, J. Flint, J. L. VanCott, J. D. Clements, and R. L. Ward. 2000. Functional mapping of protective domains and epitopes in the rotavirus VP6 protein. J. Virol. 74:11574-11580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornelis, P. 2000. Expressing genes in different Escherichia coli compartments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:450-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtiss, R., III, K. Nakayama, and S. M. Kelly. 1989. Recombinant avirulent Salmonella vaccine strains with stable maintenance and high-level expression of cloned genes in vivo. Immunol. Investig. 18:583-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Almeida, M. E. S., S. M. Newton, and L. C. Ferreira. 1999. Antibody responses against flagellin in mice orally immunized with attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains. Arch. Microbiol. 172:102-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunstan, S. J., C. P. Simmons, and R. A. Strugnell. 1998. Comparison of the abilities of different attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strains to elicit humoral immune responses against a heterologous antigen. Infect. Immun. 66:732-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ermak, T. H., P. J. Giannasca, R. Nichols, G. A. Myers, J. Nedrud, R. Weltzin, C. K. Lee, H. Kleanthous, and T. P. Monath. 1998. Immunization of mice with urease vaccine affords protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in the absence of antibodies and is mediated by MHC class II-restricted responses. J. Exp. Med. 188:2277-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galen, J. E., and M. M. Levine. 2001. Can a “flawless” live vector vaccine strain be engineered? Trends Microbiol. 9:372-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galen, J. E., J. Nair, J. Y. Wang, S. S. Wasserman, M. K. Tanner, M. B. Sztein, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Optimization of plasmid maintenance in the attenuated live vector vaccine strain Salmonella typhi CVD 908-htrA. Infect. Immun. 67:6424-6433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gentschev, I., G. Dietrich, S. Spreng, A. Kolb-Maurer, J. Daniels, J. Hess, S. H. Kaufmann, and W. Goebel. 2000. Delivery of protein antigens and DNA by virulence-attenuated strains of Salmonella typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes. J. Biotechnol. 83:19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germain, R. N., and D. H. Margulies. 1993. The biochemistry and cell biology of antigen processing and presentation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11:403-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes, L. J., J. W. Conlan, J. S. Everson, M. E. Ward, and I. N. Clarke. 1991. Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein epitopes expressed as fusions with LamB in an attenuated aroA strain of Salmonella typhimurium: their application as potential immunogens. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137(Pt. 7):1557-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess, J., I. Gentschev, D. Miko, M. Welzel, C. Ladel, W. Goebel, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1996. Superior efficacy of secreted over somatic antigen display in recombinant Salmonella vaccine induced protection against listeriosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1458-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess, J., C. Ladel, D. Miko, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1996. Salmonella typhimurium aroA− infection in gene-targeted immunodeficient mice: major role of CD4+ TCR-ab cells and IFN-γ in bacterial clearance independent of intracellular location. J. Immunol. 156:3321-3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohmann, E. L., C. A. Oletta, W. P. Loomis, and S. I. Miller. 1995. Macrophage-inducible expression of a model antigen in Salmonella typhimurium enhances immunogenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2904-2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igwe, E. I., H. Rüssmann, A. Roggenkamp, A. Noll, I. B. Autenrieth, and J. Heesemann. 1999. Rational live oral carrier vaccine design by mutating virulence-associated genes of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 67:5500-5507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen, R., and J. Tommassen. 1994. PhoE protein as a carrier for foreign epitopes. Int. Rev. Immunol. 11:113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen, R., M. Wauben, R. van der Zee, M. de Gast, and J. Tommassen. 1994. Influence of amino acids of a carrier protein flanking an inserted T-cell determinant on T-cell stimulation. Int. Immunol. 6:1187-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jose, J., F. Jahnig, and T. F. Meyer. 1995. Common structural features of IgA1 protease-like outer membrane protein autotransporters. Mol. Microbiol. 18:378-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jose, J., J. Krämer, T. Klauser, J. Pohlner, and T. F. Meyer. 1996. Absence of periplasmic DsbA oxidoreductase facilitates export of cysteine-containing passenger proteins to the Escherichia coli cell surface via the IgA beta autotransporter pathway. Gene 178:107-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klauser, T., J. Pohlner, and T. F. Meyer. 1990. Extracellular transport of cholera toxin B subunit using Neisseria IgA protease beta-domain: conformation-dependent outer membrane translocation. EMBO J. 9:1991-1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konieczny, M. P., M. Suhr, A. Noll, I. B. Autenrieth, and M. Alexander Schmidt. 2000. Cell surface presentation of recombinant (poly-) peptides including functional T-cell epitopes by the AIDA autotransporter system. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 27:321-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lattemann, C. T., J. Maurer, E. Gerland, and T. F. Meyer. 2000. Autodisplay: functional display of active β-lactamase on the surface of Escherichia coli by the AIDA-I autotransporter. J. Bacteriol. 182:3726-3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lattemann, C. T., Z. X. Yan, A. Matzen, T. F. Meyer, and H. Apfel. 1999. Immunogenicity of the extracellular copper/zinc superoxide dismutase of the filarial parasite Acanthocheilonema viteae delivered by a two-phase vaccine strain of Salmonella typhimurium. Parasite Immunol. 21:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leclerc, C., A. Charbit, A. Molla, and M. Hofnung. 1989. Antibody response to a foreign epitope expressed at the surface of recombinant bacteria: importance of the route of immunization. Vaccine 7:242-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, J. S., K. S. Shin, J. G. Pan, and C. J. Kim. 2000. Surface-displayed viral antigens on Salmonella carrier vaccine. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:645-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mastroeni, P., B. Villarreal-Ramos, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1992. Role of T cells, TNF alpha and IFN gamma in recall of immunity to oral challenge with virulent salmonellae in mice vaccinated with live attenuated aro− Salmonella vaccines. Microb. Pathog. 13:477-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maurer, J., J. Jose, and T. F. Meyer. 1997. Autodisplay: one-component system for efficient surface display and release of soluble recombinant proteins from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:794-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maurer, J., J. Jose, and T. F. Meyer. 1999. Characterization of the essential transport function of the AIDA-I autotransporter and evidence supporting structural predictions. J. Bacteriol. 181:7014-7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNeal, M. M., J. L. VanCott, A. H. Choi, M. Basu, J. A. Flint, S. C. Stone, J. D. Clements, and R. L. Ward. 2002. CD4 T cells are the only lymphocytes needed to protect mice against rotavirus shedding after intranasal immunization with a chimeric VP6 protein and the adjuvant LT(R192G). J. Virol. 76:560-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morona, R., J. Yeadon, A. Considine, J. K. Morona, and P. A. Manning. 1991. Construction of plasmid vectors with a non-antibiotic selection system based on the Escherichia coli thyA+ gene: application to cholera vaccine development. Gene 107:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newton, S. M., T. M. Joys, S. A. Anderson, R. C. Kennedy, M. E. Hovi, and B. A. Stocker. 1995. Expression and immunogenicity of an 18-residue epitope of HIV1 gp41 inserted in the flagellar protein of a Salmonella live vaccine. Res. Microbiol. 146:203-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newton, S. M. C., C. O. Jacob, and B. A. D. Stocker. 1989. Immune response to cholera toxin epitope inserted in Salmonella flagellin. Science 244:70-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noll, A., and I. B. Autenrieth. 1996. Yersinia-hsp60-reactive T cells are efficiently stimulated by peptides of 12 and 13 amino acid residues in a MHC class II (I-Ab)-restricted manner. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 105:231-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfeifer, J. D., M. J. Wick, R. L. Roberts, K. Findlay, S. J. Normark, and C. V. Harding. 1993. Phagocytic processing of bacterial antigens for class I MHC presentation to T cells. Nature 361:359-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pohlner, J., R. Halter, K. Beyreuther, and T. F. Meyer. 1987. Gene structure and extracellular secretion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae IgA protease. Nature 325:458-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruiz-Perez, F., R. Leon-Kempis, A. Santiago-Machuca, G. Ortega-Pierres, E. Barry, M. Levine, and C. Gonzalez-Bonilla. 2002. Expression of the Plasmodium falciparum immunodominant epitope (NANP4) on the surface of Salmonella enterica using the autotransporter MisL. Infect. Immun. 70:3611-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rüssmann, H., E. I. Igwe, J. Sauer, W. D. Hardt, A. Bubert, and G. Geginat. 2001. Protection against murine listeriosis by oral vaccination with recombinant Salmonella expressing hybrid Yersinia type III proteins. J. Immunol. 167:357-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rüssmann, H., H. Shams, F. Poblete, Y. Fu, J. E. Galán, and R. O. Donis. 1998. Delivery of epitopes by the Salmonella type III secretion system for vaccine development. Science 281:565-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimada, K., Y. Ohnishi, S. Horinouchi, and T. Beppu. 1994. Extracellular transport of pseudoazurin of Alcaligenes faecalis in Escherichia coli using the COOH-terminal domain of Serratia marcescens serine protease. J. Biochem. 116:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tommassen, J., M. Agterberg, R. Janssen, and G. Spierings. 1993. Use of the enterobacterial outer membrane protein PhoE in the development of new vaccines and DNA probes. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 278:396-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valentine, P. J., B. P. Devore, and F. Heffron. 1998. Identification of three highly attenuated Salmonella typhimurium mutants that are more immunogenic and protective in mice than a prototypical aroA mutant. Infect. Immun. 66:3378-3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.VanCott, J. L., S. N. Chatfield, M. Roberts, D. M. Hone, E. L. Hohmann, D. W. Pascual, M. Yamamoto, H. Kiyono, and J. R. McGhee. 1998. Regulation of host immune responses by modification of Salmonella virulence genes. Nat. Med. 4:1247-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang, D. M., N. Fairweather, L. L. Button, W. R. McMaster, L. P. Kahl, and F. Y. Liew. 1990. Oral Salmonella typhimurium (AroA−) vaccine expressing a major leishmanial surface protein (gp63) preferentially induces T helper 1 cells and protective immunity against leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 145:2281-2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]