Abstract

In the present study, we developed a cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitope minigene-transduced dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccine against Listeria monocytogenes. Murine bone marrow-derived DCs were retrovirally transduced with a minigene for listeriolysin O (LLO) 91-99, a dominant CTL epitope of L. monocytogenes, and were injected into BALB/c mice intravenously. We found that the DC vaccine was capable of generating peptide-specific CD8+ T cells exhibiting LLO 91-99-specific cytotoxic activity and gamma interferon production, leading to induction of protective immunity to the bacterium. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the retrovirally transduced DC vaccine was more effective than a CTL epitope peptide-pulsed DC vaccine and a minigene DNA vaccine for eliciting antilisterial immunity. These results provide an alternative strategy in which retrovirally transduced DCs are used to design vaccines against intracellular pathogens.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells that patrol all tissues of the body with the possible exceptions of the brain and testes. DCs capture bacteria and other pathogens. Then they migrate to regional lymphoid organs, where they present antigens (Ags) to naïve T cells (3). DCs have a distinct ability to prime naïve helper T lymphocytes and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs); thus, there has been much interest in the use of these cells for immune modulation of diseases. A number of investigators have demonstrated that DC-based vaccines, such as those pulsed with tumor-associated Ag, can generate specific antitumor immunity in vivo in murine tumor models (6, 21). A DC vaccine genetically engineered to express tumor-associated Ags is one of the most promising methods for tumor immunotherapy as it allows constitutive expression of the Ag, leading to prolonged Ag presentation in vivo (29). In the field of infectious diseases, however, there have been a few studies exploring the efficacy of DC-based vaccines (1, 19, 20, 26, 28).

Infection with intracellular pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, poses serious health problems worldwide. Efficient protection against intracellular bacteria critically depends on induction of cellular immune responses. Administration of soluble proteins may be insufficient to stimulate such responses. So far, only live attenuated vaccines are considered to be satisfactory. However, because of the low safety level of live vaccines in immunocompromised individuals and because of the variable effectiveness of these vaccines, development of new, improved vaccines which induce cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens has become a research priority (15, 27).

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive facultative intracellular bacterium that causes life-threatening infections during pregnancy and in immunocompromised individuals (13). L. monocytogenes enters eukaryotic cells in membrane-bound vesicles, and then it escapes from the vesicles, multiplies within the cell cytoplasm, and spreads directly to adjacent cells. A well-characterized mouse model of L. monocytogenes infection has yielded significant insight into the nature of innate and acquired cell-mediated immunity primarily associated with specific CD8+ CTLs (11, 31). Murine L. monocytogenes infection can, therefore, serve as a useful model for studying protective immunity to intracellular bacteria. Among the Ags recognized by the CTLs, four different epitopes are presented to CTLs by H2-Kd molecules (4, 24, 32). These epitopes are derived from bacterial virulence factors, including a sulfhydryl-activated pore-forming exotoxin, listeriolysin O (LLO), murein hydrolase p60, and metalloprotease (Mpl). Indeed, infection of BALB/c mice with a sublethal dose of L. monocytogenes induces dominant CTL responses against LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 and subdominant responses against p60 449-457 and Mpl 84-92 (4).

Previously, Harty and Bevan (14) showed that adoptive transfer of CD8+ CTLs specific for LLO 91-99 confers protection against L. monocytogenes infection. Consistent with this observation, previous studies demonstrated that DNA immunization with a minigene plasmid encoding a single dominant CTL epitope, LLO 91-99, induces strong CTL activity and confers partial protection against murine L. monocytogenes infection (30). Although the mechanisms by which the DNA vaccine achieves immunogenicity have not been fully determined so far, many studies have clearly indicated that DCs are the principal cells initiating the immune responses after DNA vaccination. DCs may be directly transfected with plasmid DNA and present Ags to CD8+ and CD4+ T cells through major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II molecules. Alternatively, proteins exogenously produced by transfected somatic cells allow DCs to take up, process, and present Ags not only to CD4+ T cells but also to CD8+ T cells via additional mechanisms, such as cross-priming (2, 5, 17, 25). Theoretically, vaccination with DCs harboring genes encoding Ags of interest would be more effective for induction of specific immunity than naked DNA vaccination. DCs engineered genetically to express the immunodominant T-cell epitope may be a promising vaccine against intracellular bacteria. In the present study, we developed a retrovirally transduced DC-based vaccine expressing LLO 91-99 and determined the ability of this vaccine to generate specific CTLs and to elicit protective immunity to murine L. monocytogenes infection. We also compared the efficacy of this vaccine for eliciting antilisterial immunity with the efficacy of a CTL epitope peptide-pulsed DC vaccine and the efficacy of a naked minigene DNA vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant retroviral vectors.

The double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding LLO 91-99, adapted to the most frequently used codons in murine genes (22, 30), was subcloned into the SmaI site of pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.), resulting in pLLO91-IRES-EGFP. A pMX-based (23) retroviral vector, pMX-LLO91-IRES-EGFP, was constructed by using an EcoRI-NotI DNA fragment of pLLO91-IRES-EGFP. The nucleotide sequences of the plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing by using an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Large-scale purification of expression vectors was conducted by using a Qiagen Plasmid Mega kit system (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.), and endotoxin was removed by Triton X-114 phase separation. Retroviral supernatant was generated by transfecting pMX-LLO91-IRES-EGFP proviral constructs into the Phoenix ecotropic packaging cell line (purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va., and used with the permission of G. P. Nolan, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, Calif.). A control retroviral vector carried only a DNA fragment containing only the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-encoding region without the LLO 91-99-encoding region.

Mice.

BALB/c mice were purchased from SLC Japan (Hamamatsu, Japan). These mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Institute for Experimental Animals, Hamamatsu University School of Medicine. All mice used in this study were between 8 and 14 weeks old. All animal experiments were performed according to the animal care guidelines of Hamamatsu University School of Medicine.

Culture of BM-DCs and transduction with retrovirus.

Bone marrow (BM)-derived DCs (BM-DCs) were cultured by using methods described by Inaba et al. (16), with some modifications. Briefly, murine BM cells were harvested from femurs and tibias of sacrificed mice. Contaminating erythrocytes were lysed with 0.83 M NH4Cl buffer, and lymphocytes were depleted with a mixture of monoclonal antibodies (GK1.5, anti-CD4 [TIB207]; HO2.2, anti-CD8 [TIB150]; B21-2, anti-H2-Ab,d [TIB229]; and RA3-3A1/6.1, anti-B-cell surface glycoprotein [TIB146]; all obtained from the American Type Culture Collection) and rabbit complement (Cedarlane, Hornby, Canada). Cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were placed in 24-well plates in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1,000 U of recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (kindly provided by Kirin Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) per ml, and 1,000 U of recombinant murine interleukin-4 (IL-4) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) per ml (complete RPMI medium) at zero time. The cells were harvested on day 6. To determine the phenotype of cultured DCs, we stained them with phosphatidylethanolamine- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against cell surface molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86, and H2-Ab; all obtained from Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) and analyzed them with an EPICS Profile-II (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.). For retroviral transduction, 1 × 106 BM cells were cultured in complete RPMI medium for 48 h and resuspended in 1 ml of the retroviral supernatant supplemented with 8 μg of Polybrene (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml, 1,000 U of recombinant murine GM-CSF per ml, and 1,000 U of recombinant murine IL-4 per ml. These cells were centrifuged at 2,500 × g at 32°C for 2 h. After centrifugation, cells were cultured in complete RPMI medium. The transduction processes were repeated on days 3 and 4. The transduction efficiency of the BM-DCs was evaluated by measuring the expression of EGFP by flow cytometry.

Preparation of LLO 91-99 peptide-pulsed DCs (LLO91-pulsed DCs).

The LLO 91-99 peptide, GYKDGNEYI, representing an H2-Kd-restricted immunodominant CTL epitope spanning amino acid residues 91 to 99 of LLO, was synthesized by BEX (Tokyo, Japan). BM-DCs from BALB/c mice after 6 days of culture were resuspended in RPMI 1640 at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml and pulsed with 5 μM LLO 91-99 peptide and human β2-microglobulin (Sigma Chemical Co.) (21) for 2 h at room temperature with gentle mixing.

Immunization with DCs.

After two washes in phosphate-buffered saline, 105 retrovirus-transduced or LLO91-pulsed DCs in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline were injected intravenously into mice twice with a 1-week interval between the injections.

Plasmid DNA immunization with gene gun bombardment.

Construction of p91mam has been described previously (30). For DNA immunization with the Helios gene gun system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.), the cartridge containing DNA-coated gold particles was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then 0.5 mg of gold particles was coated with 2 μg of plasmid DNA, and injection was carried out by using 0.5 mg of gold/shot. To immunize mice, the shaved abdominal skin was wiped with 70% ethanol, the spacer of the gene gun was held directly against the abdominal skin, and the device was discharged at a helium discharge pressure of 400 lb/in2. Mice were injected with 2 μg of plasmid twice with a 1-week interval between the injections.

Preparation of splenocyte culture supernatants for evaluation of IFN-γ production.

Pools of spleen cell suspensions (2 × 106 cells/ml) from groups of mice immunized with DCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in 24-well plates in the presence of 5 μM LLO 91-99 peptide at 37°C in 5% CO2. Supernatants were harvested 5 days later and stored at −20°C until they were assayed for gamma interferon (IFN-γ). The IFN-γ concentration was measured by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described previously (34).

CTL assay.

Eight weeks after the last immunization, immune spleen cells were cocultured in 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 107 cells/well for 5 days with 2 × 107 syngeneic splenocytes per ml; the splenocytes had been treated with 100 μg of mitomycin C (Kyowa Hakko, Tokyo, Japan) per ml and pulsed with 5 μM LLO 91-99 peptide for 2 h at 37°C. Each well also received 10 U of human recombinant IL-2 (Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, N.J.) per ml. Cell-mediated cytotoxicity was measured by using a conventional 51Cr release assay as described previously (30). The target cells used in this study were J774 murine macrophage-like cells (H2d) pulsed with the peptide at a concentration of 5 μM for 1.5 h at 37°C. Target cells at a concentration of 104 cells/well were incubated for 5 h in triplicate at 37°C with serial dilutions of effector cells, and the level of specific lysis of the target cells was determined by using the following equation: percentage of specific lysis = [(experimental counts per minute − spontaneous counts per minute)/(total counts per minute − spontaneous counts per minute)] × 100.

Bacterial infection and evaluation of antilisterial immunity.

L. monocytogenes strain EGD, kindly provided by M. Mitsuyama (Kyoto University), was kept virulent by in vivo passage. For inoculation, a seed culture of L. monocytogenes was grown overnight in Trypticase soy broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) at 37°C in a bacterial shaker and suitably diluted with phosphate-buffered saline. The exact infection dose was assessed retrospectively by plating. Eight weeks after the last immunization, immunized mice were challenged with 3 × 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes. Seventy-two hours after the challenge infection, the numbers of bacteria in spleens were determined by plating 10-fold dilutions of tissue homogenates on Trypticase soy agar plates.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical evaluation of differences between means for experimental groups was performed by using Student's t test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Retroviral transduction of BM-DCs and their phenotype.

DCs were generated from murine BM by culturing with GM-CSF plus IL-4 as previously described (16). More than 70% of the cultured cells were determined to be DCs (data not shown).

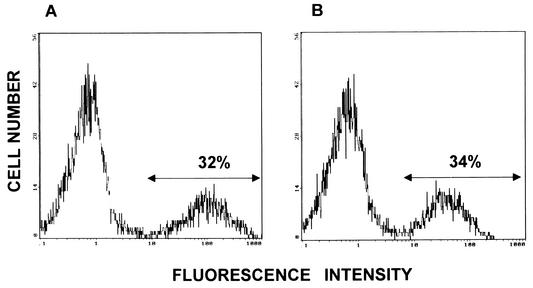

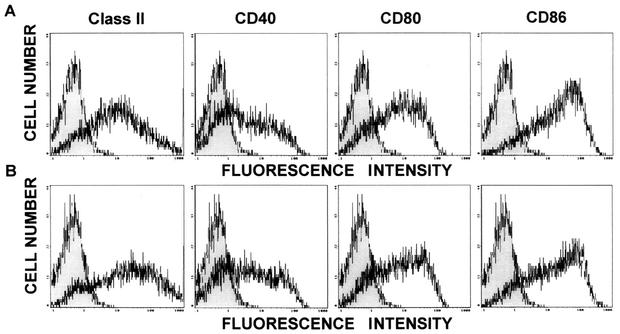

LLO91-EGFP and control EGFP retroviruses were transfected into the DCs. To assess the efficiencies of transduction of the LLO91-EGFP and control EGFP retroviruses into DCs, expression of EGFP was evaluated by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1, the levels of expression of EGFP in EGFP- and LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs were similar (26.2 to 41.2%). Then we examined the patterns of expression of various cell surface molecules by flow cytometry. DCs transduced with an LLO 91-99-encoding retrovirus (LLO91-transduced DCs) and nontransduced DCs expressed similar amounts of CD40, CD80, CD86, and MHC class II molecules (Fig. 2), indicating that retrovirus transduction into DCs does not affect the phenotype of the DCs. Furthermore, we performed CTL assays using spleen cells of mice immunized with a sublethal dose of L. monocytogenes as the effector cells and LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs as the target cells. The magnitude of the specific cell lysis of LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs was much greater than that of control DCs (data not shown), indicating that the LLO 91-99 peptide is efficiently expressed and presented on the surface of LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs.

FIG. 1.

Expression of EGFP in retrovirally transduced DCs. The transduction efficiencies were evaluated by flow cytometry of the expression of EGFP in LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs (A) and EGFP-transduced DCs (B). DCs were transduced by the centrifugal enhancement method on days 2, 3, and 4 of culture as described in Materials and Methods. EGFP expression was determined by flow cytometry on day 7. Representative results are shown.

FIG. 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of nontransduced DCs (A) and LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs (B) as determined by flow cytometry. Expression of cell surface molecules on DCs (MHC class II, CD40, CD80, and CD86) was evaluated by flow cytometry. The data are representative data for three independent experiments in which similar results were obtained. The shaded areas indicate binding by isotype-matched control antibodies.

LLO91-transduced DC vaccination generates LLO 91-99-specific IFN-γ-producing cells.

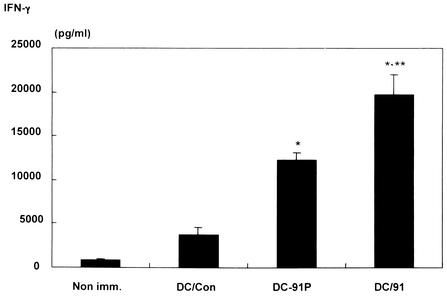

We evaluated LLO 91-99 peptide-specific IFN-γ production by spleen cells from mice immunized with the LLO91-transduced DCs and compared it with that by spleen cells from mice immunized with LLO91-pulsed DCs. Upon stimulation with LLO 91-99 peptide, spleen cells from LLO91-transduced DC-vaccinated mice produced significantly higher levels of IFN-γ than spleen cells from mice immunized with control EGFP-transduced DCs and LLO91-pulsed DCs produced (Fig. 3), suggesting that immunization with LLO91-transduced DCs efficiently generates LLO 91-99-specific IFN-γ-producing cells in vivo. Of interest is the finding that spleen cells from mice immunized with control untreated DCs produced somewhat larger amounts of IFN-γ than spleen cells from naïve mice produced (Fig. 3). We also evaluated the levels of IFN-γ production by spleen cells from mice immunized with LLO91-transduced DCs, LLO91-pulsed DCs, and control EGFP-transduced DCs without LLO 91-99 peptide stimulation. The levels were very low compared with the levels observed with peptide stimulation, but they were higher than the level of production by spleen cells from naïve mice (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ secretion by LLO 91-99-stimulated splenocytes from mice immunized with EGFP- and LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs or LLO91-pulsed DCs. BALB/c mice were immunized intravenously with EGFP- and LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs or LLO91-pulsed DCs twice with a 1-week interval between the immunizations. Spleen cells from mice immunized with EGFP- or LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs (DC/Con and DC/91, respectively) or LLO91-pulsed DCs (DC-91P) or from naïve mice (Non imm.) were harvested 8 weeks after the last immunization and stimulated in vitro by culturing in the presence of the LLO 91-99 peptide for 5 days. The concentrations of IFN-γ in the culture supernatants were determined by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The data are the means ± standard deviations for five mice for each experimental group. One asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.001) compared with DC/Con, and two asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.01) compared with DC-91P.

LLO91-transduced DC vaccination generates LLO 91-99-specific CTLs.

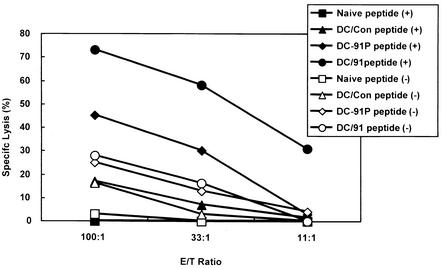

We next determined whether LLO 91-99-specific CTLs were generated in vivo following LLO91-EGFP-transduced DC or LLO91-pulsed DC vaccination. We observed less than 30% lysis of LLO 91-99-pulsed J774 target cells without in vitro peptide restimulation (data not shown). After in vitro restimulation of immune spleen cells with the LLO 91-99 peptide, the cells from LLO91-EGFP-transduced DC-immunized mice were able to lyse the peptide-pulsed J774 cells more effectively than the cells from control DC-immunized mice were (Fig. 4). The CTL activity of spleen cells from mice immunized with LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs was similar to or somewhat weaker than that of spleen cells from mice immunized with a sublethal dose (103 CFU) of L. monocytogenes (data not shown). In addition, the CTL activity of spleen cells from mice immunized with LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs was stronger than that of spleen cells from mice immunized with LLO91-pulsed DCs (Fig. 4). Furthermore, these CTL activities correlated well with the levels of LLO 91-99-specific IFN-γ production observed.

FIG. 4.

Induction of CTL activity by LLO91-EGFP-transduced DC immunization. Spleen cells from mice immunized with EGFP-transduced DCs (DC/Con) (▴ and ▵), LLO91-pulsed DCs (DC-91P) (♦ and ⋄), and LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs (DC/91) (• and ○) were harvested 8 weeks after the last immunization and stimulated in vitro with LLO 91-99 peptide-pulsed spleen cells for 5 days. The percentage of specific lysis was determined by using J774 cells (H2d) pulsed with (solid symbols) or without (open symbols) LLO 91-99 peptide as target cells. Immune spleen cells (effectors) were incubated with target cells in the effector-to-target-cell ratios (E/T Ratio) indicated on the x axis. Spleen cells from naïve mice were also harvested, and the same assay was performed simultaneously (▪ and □) as a control assay. The data are representative of data obtained in four independent experiments.

LLO91-transduced DC vaccination provides protective immunity to a subsequent challenge with viable L. monocytogenes.

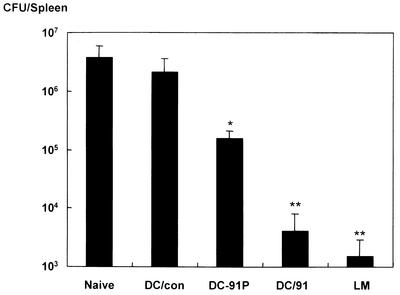

To ascertain whether immune responses in mice immunized with the DC vaccines were efficiently protective against lethal listerial infection, the vaccinated animals were challenged intravenously with L. monocytogenes, and the protection was assessed by quantifying the numbers of L. monocytogenes cells recovered from the spleens. The protection was highly significant in mice that received LLO91-transduced DCs compared with the protection in mice that received control DCs and LLO91-pulsed DCs and in untreated mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5). Although the spleens of mice vaccinated with L. monocytogenes appeared to contain fewer bacteria than the spleens of mice vaccinated with LLO91-transduced DCs, the difference in the mean bacterial numbers in the spleens of the two groups was not statistically significant.

FIG. 5.

Induction of protective immunity by immunization with LLO91-transduced DCs. Mice were immunized with EGFP-transduced DCs (DC/Con), LLO91-EGFP-transduced DCs (DC/91), or LLO91-pulsed DCs (DC-91P) twice with a 1-week interval between the immunizations or with a single sublethal dose (103 CFU) of L. monocytogenes (LM). Eight weeks after the last immunization, the mice were challenged with 3 × 104 CFU of L. monocytogenes. The numbers of bacteria in spleens from the immunized mice and naïve mice (Naive) were determined 72 h after challenge infection by plating 10-fold dilutions of tissue homogenates on plates. The data are the means ± standard deviations for five mice for each experimental group. One asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.01) compared with Naive and DC/Con. Two asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.01) compared with Naive, DC/Con, and DC-91P.

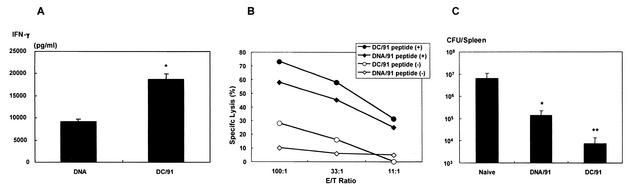

Vaccination with LLO91-DCs is more effective than vaccination with the minigene DNA vaccine administered with the gene gun system. Previously, it was reported that LLO 91-99 minigene DNA vaccination efficiently evoked the epitope-specific CTL activity and consequently protective immunity to lethal infection by L. monocytogenes (30). To compare the efficacies of the genetically modified DC-based vaccine and the minigene DNA vaccine, BALB/c mice were also immunized with plasmid DNA by using the gene gun system. Upon stimulation with the LLO 91-99 peptide, splenocytes from LLO91-DC-vaccinated mice produced significantly higher levels of IFN-γ than splenocytes from mice immunized with the minigene DNA produced (Fig. 6A). In addition, the percentage of specific lysis of LLO 91-99 peptide-pulsed target cells tended to be higher with CTLs from genetically modified DC-vaccinated mice than with CTLs from the DNA-vaccinated mice (Fig. 6B). Finally, the DC vaccine induced significantly stronger protection against lethal infection by L. monocytogenes than the minigene DNA vaccine induced (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Retrovirally transduced DC vaccination is more effective than naked DNA vaccination. (A) IFN-γ secretion by LLO 91-99 peptide-stimulated splenocytes from mice immunized with the LLO 91-99 minigene DNA vaccine (DNA) or the LLO91-EGFP-transduced DC vaccine (DC/91). IFN-γ secretion by spleen cells from the immunized mice was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The data are means ± standard deviations for five mice for each experimental group. An asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.01). (B) CTL activity of spleen cells from mice immunized with the LLO 91-99 minigene DNA vaccine (DNA/91) or the LLO91-EGFP-transduced DC vaccine (DC/91). Spleen cells from mice immunized with LLO91-transduced DCs (• and ○) or with LLO 91-99 minigene plasmid DNA (♦ and ⋄) were harvested 8 weeks after the last immunization and stimulated in vitro with LLO91-pulsed splenocytes for 5 days. Then the cells were used for the CTL assay as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The percentage of specific lysis was determined by using J774 cells (H2d) pulsed with the LLO 91-99 peptide (solid symbols) or medium alone (open symbols). Immune spleen cells (effectors) were incubated with target cells in the effector-to-target-cell ratios (E/T Ratio) indicated on the x axis. The data are representative of data obtained in four independent experiments. (C) Induction of protective immunity in mice immunized with the LLO 91-99 minigene DNA vaccine (DNA/91) or the LLO91-EGFP-transduced DC vaccine (DC/91). Mice immunized with the vaccines were examined by the in vivo L. monocytogenes protection assay as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Naïve mice (Naive) were also examined as controls. The data are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments. One asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.01) compared with Naive, and two asterisks indicate statistical significance (P < 0.01) compared with Naive and DNA/91.

DISCUSSION

As DCs are the most powerful antigen-presenting cells that initiate the primary immune responses, they have been attractive targets for developing vaccines against tumors (6, 21, 27). However, the potential of DCs for development of vaccines against intracellular bacteria has not been explored very much. Here, we evaluated DC vaccination against intracellular bacteria with a murine L. monocytogenes infection system. We analyzed a vaccination whose target is a single immunodominant CTL epitope of L. monocytogenes in order to make evaluation of the results clear.

There are several strategies for using DCs as vaccines, including ex vivo pulses with pathogen-derived peptides or Ags and transfer of genes encoding Ags to DCs. Viral and nonviral vector systems have been developed to obtain efficient gene transfer and stable gene expression in DCs. Among these systems, the retroviral transduction system is the most advantageous for long-term Ag presentation in vivo, as this system lets the transgene integrate into the chromosome, leading to gene expression throughout the life of the cell and its progeny (12, 18). In the present study, therefore, we used the retroviral transduction system to deliver Ags to DCs. We evaluated the immunizing effects of retrovirally transduced DC vaccination and compared them with those of peptide-pulsed DC vaccination. Since the transduction efficiency with retroviral vectors is relatively low, we employed the centrifugal enhancement method. Our data showed that BM-DCs were successfully transduced by recombinant retroviruses with 26.2 to 41.2% transduction efficiencies and that the transduced DCs still expressed the LLO 91-99 peptide. We found that the retrovirally transduced DC vaccine was more effective than the peptide-pulsed DC vaccine for eliciting antilisterial immunity. The stable expression of CTL epitope peptides on DCs is necessary for generating potent CTLs possessing lytic activity against infected cells. However, peptides pulsed onto DCs may stay bound to MHC molecules only transiently, and the peptide may be bound to MHC molecules in an unnatural way. In contrast, endogenous Ag synthesis within retrovirally transduced DCs ensures direct access of the Ag to the MHC class I Ag processing pathway in a natural way, efficiently stimulating Ag-specific CTLs (7, 9). In this context, retrovirally transduced DC vaccination may have important advantages over antigenic peptide-pulsed DC vaccination (29). Our data clearly demonstrate that the DC vaccine retrovirally transduced with DNA encoding a single immunodominant CTL epitope, LLO 91-99 of L. monocytogenes, protects against lethal challenge by the bacterium, and this protection is much more potent than that induced by peptide-pulsed DC vaccination.

Furthermore, we compared the efficacy of the retrovirally transduced DC vaccine with that of a naked DNA vaccine delivered with the gene gun system. Consistent with previous studies (30, 35), the present data showed that gene gun-mediated inoculation of plasmid DNA encoding LLO 91-99 induced the peptide-specific CTLs, as well as protective immunity to lethal infection by L. monocytogenes. After lethal listerial challenge, however, mice immunized with LLO91-transduced DCs had 1 log fewer CFU of L. monocytogenes in their spleens than mice immunized with the minigene DNA vaccine had. These data indicate that the antilisterial immunity induced by the genetically modified DC vaccine is much more effective than that induced by the naked DNA vaccine. The precise mechanisms responsible for the difference between the immunizing effects of the DC vaccine and the naked DNA vaccine are not clear. However, the genetically modified DC vaccine generated more CTL activity, as well as higher levels of IFN-γ secretion from splenocytes, than the naked DNA vaccine generated, which may have contributed to the enhanced protection observed in mice immunized with the DC vaccine. DCs have been shown to act as the principal cells initiating the immune responses after DNA vaccination by direct transfection and/or cross-priming (5, 8, 10, 17, 25). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that introduction of genes encoding Ags directly into DCs is superior to naked DNA vaccination into the skin for developing protective immunity. In support of our data, a recent study demonstrated that immunization with murine DCs transfected with human gp100, a human melanoma-associated Ag, elicited more potent antitumor immunity than immunization with naked DNA encoding gp100 (33). Collectively, although DNA vaccines are more manageable in clinical applications than DC-based vaccines, genetically modified DC vaccines may be more effective than naked DNA vaccines for inducing protective immunity to intracellular bacteria.

This is the first report describing a highly efficacious vaccine against intracellular bacteria in which DCs retrovirally transduced with a minigene encoding a single immunodominant CTL epitope are used. Our findings should lead to a new strategy for creating vaccines against intracellular bacteria in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. P. Nolan (Stanford University) for permission to use the Phoenix ecotropic packaging cell line and M. Mitsuyama (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) for providing L. monocytogenes strain EGD. We also thank Y. Nishioka (University of Tokushima, Tokushima, Japan) for his helpful advice concerning retrovirus transduction to DCs.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (grant 11670260 to T.N., grant 13670268 to Y.K., and grant 13670595 to T.S.) and by a grant from the Shizuoka Research and Education Foundation (to Y.K.).

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahuja, S. S., R. L. Reddick, N. Sato, E. Montalbo, V. Kostecki, W. Zhao, M. J. Dolan, P. C. Melby, and S. K. Ahuja. 1999. Dendritic cell (DC)-based anti-infective strategies: DCs engineered to secrete IL-12 are a potent vaccine in a murine model of an intracellular infection. J. Immunol. 163:3890-3897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akbari, O., N. Panjwani, S. Garcia, R. Tascon, D. Lowrie, and B. Stockinger. 1999. DNA vaccination: transfection and activation of dendritic cells as key events for immunity. J. Exp. Med. 189:169-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busch, D. H., and E. G. Pamer. 1998. MHC class I/peptide stability: implications for immunodominance, in vitro proliferation, and diversity of responding CTL. J. Immunol. 160:4441-4448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casares, S., K. Inaba, T. D. Brumeanu, R. M. Steinman, and C. A. Bona. 1997. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells after immunization with DNA encoding a major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted viral epitope. J. Exp. Med. 186:1481-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celluzzi, C. M., J. I. Mayordomo, W. J. Storkus, M. T. Lotze, and L. D. Falo, Jr. 1996. Peptide-pulsed dendritic cells induce antigen-specific CTL-mediated protective tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 183:283-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chassin, D., M. Andrieu, W. Cohen, B. Culmann-Penciolelli, M. Ostankovitch, D. Hanau, and J. G. Guillet. 1999. Dendritic cells transfected with the nef genes of HIV-1 primary isolates specifically activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes from seropositive subjects. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:196-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho, J. H., J. W. Youn, and Y. C. Sung. 2001. Cross-priming as a predominant mechanism for inducing CD8(+) T cell responses in gene gun DNA immunization. J. Immunol. 167:5549-5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Condon, C., S. C. Watkins, C. M. Celluzzi, K. Thompson, and L. D. Falo, Jr. 1996. DNA-based immunization by in vivo transfection of dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2:1122-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombes, B. K., and J. B. Mahony. 2001. Dendritic cell discoveries provide new insight into the cellular immunobiology of DNA vaccines. Immunol. Lett. 78:103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cossart, P., and J. Mengaud. 1989. Listeria monocytogenes, a model system for the molecular study of intracellular parasitism. Mol. Biol. Med. 6:463-474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunbar, C. E., N. E. Seidel, S. Doren, S. Sellers, A. P. Cline, M. E. Metzger, B. A. Agricola, R. E. Donahue, and D. M. Bodine. 1996. Improved retroviral gene transfer into murine and Rhesus peripheral blood or bone marrow repopulating cells primed in vivo with stem cell factor and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11871-11876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gellin, B. G., and C. V. Broome. 1989. Listeriosis. JAMA 261:1313-1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harty, J. T., and M. J. Bevan. 1992. CD8+ T cells specific for a single nonamer epitope of Listeria monocytogenes are protective in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 175:1531-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hess, J., U. Schaible, B. Raupach, and S. H. E. Kaufmann. 2000. Exploring the immune system: toward new vaccines against intracellular bacteria. Adv. Immunol. 75:1-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaba, K., M. Inaba, N. Romani, H. Aya, M. Deguchi, S. Ikehara, S. Muramatsu, and R. M. Steinman. 1992. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 176:1693-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwasaki, A., C. A. Torres, P. S. Ohashi, H. L. Robinson, and B. H. Barber. 1997. The dominant role of bone marrow-derived cells in CTL induction following plasmid DNA immunization at different sites. J. Immunol. 159:11-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay, M. A., J. C. Glorioso, and L. Naldini. 2001. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat. Med. 7:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikuchi, T., S. Worgall, R. Singh, M. A. Moore, and R. G. Crystal. 2000. Dendritic cells genetically modified to express CD40 ligand and pulsed with antigen can initiate antigen-specific humoral immunity independent of CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 6:1154-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manickan, E., S. Kanangat, R. J. Rouse, Z. Yu, and B. T. Rouse. 1997. Enhancement of immune response to naked DNA vaccine by immunization with transfected dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 61:125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayordomo, J. I., T. Zorina, W. J. Storkus, L. Zitvogel, C. Celluzzi, L. D. Falo, C. J. Melief, S. T. Ildstad, W. M. Kast, A. B. Deleo, and M. T. Lotze. 1995. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells pulsed with synthetic tumour peptides elicit protective and therapeutic antitumour immunity. Nat. Med. 1:1297-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagata, T., M. Uchijima, A. Yoshida, M. Kawashima, and Y. Koide. 1999. Codon optimization effect on translational efficiency of DNA vaccine in mammalian cells: analysis of plasmid DNA encoding a CTL epitope derived from microorganisms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 261:445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onishi, M., S. Kinoshita, Y. Morikawa, A. Shibuya, J. Phillips, L. L. Lanier, D. M. Gorman, G. P. Nolan, A. Miyajima, and T. Kitamura. 1996. Applications of retrovirus-mediated expression cloning. Exp. Hematol. 24:324-329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pamer, E. G., A. J. A. M. Sijts, M. S. Villanueva, D. H. Busch, and S. Vijh. 1997. MHC class I antigen processing of Listeria monocytogenes proteins: implications for dominant and subdominant CTL responses. Immunol. Rev. 158:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porgador, A., K. R. Irvine, A. Iwasaki, B. H. Barber, N. P. Restifo, and R. N. Germain. 1998. Predominant role for directly transfected dendritic cells in antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells after gene gun immunization. J. Exp. Med. 188:1075-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranieri, E., W. Herr, A. Gambotto, W. Olson, D. Rowe, P. D. Robbins, L. S. Kierstead, S. C. Watkins, L. Gesualdo, and W. J. Storkus. 1999. Dendritic cells transduced with an adenovirus vector encoding Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2B: a new modality for vaccination. J. Virol. 73:10416-10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seder, R. A., and A. V. Hill. 2000. Vaccines against intracellular infections requiring cellular immunity. Nature 406:793-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw, J. H., V. R. Grund, L. Durling, and H. D. Caldwell. 2001. Expression of genes encoding Th1 cell-activating cytokines and lymphoid homing chemokines by Chlamydia-pulsed dendritic cells correlates with protective immunizing efficacy. Infect. Immun. 69:4667-4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Specht, J. M., G. Wang, M. T. Do, J. S. Lam, R. E. Royal, M. E. Reeves, S. A. Rosenberg, and P. Hwu. 1997. Dendritic cells retrovirally transduced with a model antigen gene are therapeutically effective against established pulmonary metastases. J. Exp. Med. 186:1213-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchijima, M., A. Yoshida, T. Nagata, and Y. Koide. 1998. Optimization of codon usage of plasmid DNA vaccine is required for the effective MHC class I-restricted T cell responses against an intracellular bacterium. J. Immunol. 161:5594-5599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unanue, E. R. 1997. Study in listeriosis show the strong symbiosis between the innate cellular system and the T-cell response. Immunol. Rev. 158:11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vijh, S., and E. G. Pamer. 1997. Immunodominant and subdominant CTL responses to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J. Immunol. 158:3366-3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, S., C. E. Vervaert, J. Burch, Jr., J. Grichnik, H. F. Seigler, and T. L. Darrow. 1999. Murine dendritic cells transfected with human GP100 elicit both antigen-specific CD8(+) and CD4(+) T-cell responses and are more effective than DNA vaccines at generating anti-tumor immunity. Int. J. Cancer 83:532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida, A., Y. Koide, M. Uchijima, and T. O. Yoshida. 1995. Dissection of strain difference in acquired protective immunity against Mycobacterium bovis Calmette-Guerin bacillus (BCG). Macrophages regulate the susceptibility through cytokine network and the induction of nitric oxide synthase. J. Immunol. 155:2057-2066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida, A., T. Nagata, M. Uchijima, T. Higashi, and Y. Koide. 2000. Advantage of gene gun-mediated over intramuscular inoculation of plasmid DNA vaccine in reproducible induction of specific immune responses. Vaccine 18:1725-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]