Abstract

Bioinformatics tools have the potential to accelerate research into the design of vaccines and diagnostic tests by exploiting genome sequences. The aim of this study was to assess whether in silico analysis could be combined with in vitro screening methods to rapidly identify peptides that are immunogenic during Mycobacterium bovis infection of cattle. In the first instance the M. bovis-derived protein ESAT-6 was used as a model antigen to describe peptides containing T-cell epitopes that were frequently recognized across mammalian species, including natural hosts for tuberculosis (humans and cattle) and small-animal models of tuberculosis (mice and guinea pigs). Having demonstrated that some peptides could be recognized by T cells from a number of M. bovis-infected hosts, we tested whether a virtual-matrix-based human prediction program (ProPred) could identify peptides that were recognized by T cells from M. bovis-infected cattle. In this study, 73% of the experimentally defined peptides from 10 M. bovis antigens that were recognized by bovine T cells contained motifs predicted by ProPred. Finally, in validating this observation, we showed that three of five peptides from the mycobacterial antigen Rv3019c that were predicted to contain HLA-DR-restricted epitopes were recognized by T cells from M. bovis-infected cattle. The results obtained in this study support the approach of using bioinformatics to increase the efficiency of epitope screening and selection.

The importance of gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-secreting CD4+ T cells in the immune responses to tuberculous infections has been well established in small-animal models as well as in natural host species (15). For example, experimental infection of cattle with Mycobacterium bovis, the causative agent of bovine tuberculosis (TB), results in strong and sustained IFN-γ responses as early as 2 weeks postinfection (46). This observation is the basis of novel diagnostic tests based on the in vitro production of IFN-γ following stimulation of whole blood with tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) (50). However, the use of PPD is associated with specificity constraints, especially in the face of vaccination with M. bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) (3, 6). Protein cocktails based on antigens that are present in M. bovis but absent in BCG can be used to differentiate between BCG-vaccinated and M. bovis-infected cattle (5, 48). An alternative approach to using recombinant proteins is the application of synthetic peptides derived from antigens such as those described above. We have provided proof of principle that this is a promising approach by demonstrating that a cocktail of 10 peptides derived from ESAT-6 and CFP-10 detected around 80% of cattle naturally infected with M. bovis tested, whereas T cells from noninfected or BCG-vaccinated calves did not recognize this peptide cocktail (49). However, peptides from additional mycobacterial antigens will have to be identified and incorporated into such diagnostic reagents to improve sensitivity to a level similar to or better than that achieved with PPD. The elucidation of the genome sequence of M. tuberculosis (10) and M. bovis will greatly facilitate this endeavor.

Peptides suitable for inclusion into diagnostic reagents targeted at highly major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-heterogeneous populations will have to be recognized promiscuously, i.e., in the context of more than one MHC. Such promiscuous determinants can be found readily in mycobacterial antigens and have been described in the context of human, murine (reviewed in reference 45), and bovine (22, 23, 35, 36, 47) MHC class II molecules. The bovine MHC complex (BoLA) is highly polymorphic, with one DR gene pair (monomorphic DRA and polymorphic DRB3 with more than 70 described alleles) and one or two DQ gene pairs (with around 40 described alleles) expressed per haplotype (reviewed in references 14 and 21). Interestingly, it has been found that despite controlled breeding, cattle still exhibit high MHC diversity (14).

The conventional method for identifying peptides recognized by T cells is the empirical experimental screen of sets of highly overlapping peptides, which, in the case of larger antigens, can be a costly and time-consuming undertaking. However, the discovery of MHC-binding motifs has lead to the development of a number of pattern-matching programs predicting MHC class I- and class II-restricted T-cell epitopes. Algorithms predicting mainly human and murine class I- and class II-restricted epitopes have been based on MHC-binding motifs (24, 27, 39) and artificial neural networks (19), as well as structural approaches (1, 24, 27, 39). A refinement of prediction algorithms using binding motifs, called matrix-based selection, has been described for both class I- and class II-restricted epitopes. This is based on the construction of a matrix of all possible amino acid side chain interactions for individual MHC-binding motifs (12, 18, 40). Advances in this approach, using so-called virtual matrices, are based on the observation that most pockets in the HLA-DR groove are shaped by clusters of polymorphic residues and that each HLA-DR pocket can be characterized by the representation of the interaction of all natural amino acid residues with a given pocket (pocket profiles). Sturniolo and coworkers (43) demonstrated that pocket profiles are almost independent of the remaining HLA-DR cleft and that a relatively small database of profiles was sufficient to generate a large number of virtual HLA-DR matrices, representing the majority of human HLA-DR peptide-binding specificities. Prediction programs applying virtual matrices to predict human DR-restricted epitopes have been described previously (41, 43) and have been used to predict potential HLA-DR-restricted determinants in, e.g., tumor antigens (8, 42). However, only a few binding motifs for BoLA class I-restricted epitopes have been described, and none have been described for BoLA class II-restricted determinants. Thus, no prediction tools are available to predict BoLA class II-restricted peptides.

In this study we used the small M. bovis-derived protein ESAT-6 as a model antigen and were able to describe peptides containing T-cell epitopes that were frequently recognized across different mammalian species (humans, mice, cattle, and guinea pigs). Based on these observations we postulated that human prediction programs could also identify peptides recognized by bovine T cells. By employing the virtual-matrix-based prediction program ProPred (41) we could show that this was indeed possible because it predicted epitopes on ca. 73% of the described empirically defined BoLA promiscuous peptides from 10 M. bovis antigens. Validating this observation, we could show that three of five peptides predicted to contain HLA-DR-restricted epitopes from Rv3019c, a mycobacterial antigen not previously described in bovine TB, were recognized by T cells from M. bovis-infected cattle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. bovis infections. (i) Cattle.

Calves ca. 6 months old (Friesian, Friesian cross-breeds, Limousin, and Angus) were infected with an M. bovis field strain from Great Britain (AF 2122/97) by intratracheal instillation of 2 × 104 CFU as described previously (7, 48). Bovine TB was confirmed in these animals by the presence of visible lesions in lymph nodes and lungs found at postmortem examinations, by the histopathological examination of lesioned tissues, and by the culture of M. bovis from tissue samples collected from lymph nodes and lungs. Heparinized blood samples were obtained between 14 and 20 weeks after infection when strong and sustained in vitro tuberculin responses were observed. Data from a total of 30 experimentally infected cattle are presented in this study. One naturally infected animal was also included in the study.

(ii) Mice.

Groups of three to five C57BL/10 (H-2b), C57BL/10.BR (H-2k), and C57BL/10.D2 (H-2d) mice (Charles River UK Ltd., Margate, United Kingdom) were infected with 104 CFU of M. bovis AF2122/97 in a 50-μl volume by the intravenous route. Splenocytes were prepared 4 weeks postinfection from the infected animals, pooled, and used in lymphocyte transformation assays (see below).

(iii) Guinea pigs.

Outbred female Duncan-Hartley guinea pigs weighing 350 to 400 g (Charles River UK Ltd.) were infected with 100 CFU of M. bovis AN5 in a 0.25-ml volume of phosphate-buffered saline by intramuscular injection into the flexor muscles of the right hind leg. Heparinized blood was obtained 3 weeks postinfection by cardiac puncture.

Antigens and peptides. (i) Antigens.

Bovine (PPD-B) and avian (PPD-A) tuberculin were obtained from the Tuberculin Production Unit at the Veterinary Laboratories Agency-Weybridge (VLA, Addlestone, United Kingdom) and used in culture at 10 μg/ml. Recombinant Rv3019c protein was obtained from Lionex Ltd. (Braunschweig, Germany).

(ii) Peptides.

Peptides were either synthesized at the VLA by solid-phase peptide synthesis as described previously (49) or purchased from Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom. Purchased peptides were synthesized in the same way as those produced at the VLA. Peptide purity (at least 90%, but generally >95%) and sequence fidelity were confirmed by analytical reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and by electron-spray mass spectrometry, respectively. Peptides were used at 10 to 25 μg/ml in the in vitro assays described below.

Preparation of bovine PBMC.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from heparinized blood by Histopaque-1077 (Sigma Aldrich, Poole, United Kingdom) gradient centrifugation and suspended in tissue culture medium (cattle TCM) composed of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% CPSR-1 (controlled process serum replacement type-1; Sigma Aldrich), nonessential amino acids (Sigma Aldrich), and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/ml) (Sigma Aldrich).

Peptide-specific short-term bovine T-cell lines.

A method developed to study human T-cell responses (2) was modified for use with bovine lymphocytes. Briefly, adherent cells were prepared from bovine PBMC by incubation of 106 cells in 0.1-ml aliquots for 2 h in 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates, after which nonadherent cells were removed by at least three washes with cattle TCM warmed to 37°C. Adherent cells were then kept in culture for an additional 14 days as a source of antigen-presenting cells. In parallel, PBMC in TCM were stimulated in 24-well plates (106 PBMC/ml; 1-ml aliquots) with synthetic peptides derived from ESAT-6 at 20 μg/ml. PBMC cultures were fed every 3 to 4 days with recombinant human interleukin-2 (to a final concentration of 10 U/ml; Sigma Aldrich). After 2 weeks in culture, short-term lines were harvested and washed four times by centrifugation in cattle TCM and resuspended in cattle TCM. Cells (105/well) were added to the adherent cells cultured in 96-well plates. Synthetic peptides were then added to these cultures to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. After 2 days in culture at 37°C with 5% CO2, supernatants were harvested and the level of IFN-γ in these supernatants was determined using the BOVIGAM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Biocore AH, Omaha, Nebr.) as described in the kit instructions.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay.

Direct enzyme-linked immunospots (ELISPOTs) were enumerated as described previously (49). Briefly, ELIPSOT plates (Immobilon-P polyvinylidene fluoride membranes; Millipore, Molsheim, France) were coated overnight at 4°C with the bovine IFN-γ-specific monoclonal antibody 2.2.1. Unbound antibody was removed by washing, and the wells were blocked with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies). PBMC (2 × 105 to 4 × 105/well suspended in cattle TCM) were then added and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator for 24 h. Peptides were used at concentrations of 10 to 25 μg/ml. Spots were developed with rabbit serum specific for IFN-γ followed by incubation with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated monoclonal antibody specific for rabbit immunoglobulin G (Sigma Aldrich). The spots were visualized with BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate)-nitroblue tetrazolium substrate (Sigma Aldrich). The monoclonal antibody 2.2.1 was kindly supplied by D. Godson (VIDO, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada).

Guinea pig and murine lymphocyte transformation assays. (i) Mice.

Splenocytes (4 × 105 cells/well) from M. bovis-infected mice were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, nonessential amino acids, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Mononuclear cells were cultured in triplicate (0.2-ml volumes) for 3 days at 37°C and 5% CO2 in flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates in the presence of antigen and radiolabeled during the final 4 h of culture with [3H]thymidine (37 kBq/well; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). The cultures were harvested onto glass fiber filters and counted on a beta counter. Results were expressed as the stimulation index (SI), defined as counts per minute observed in antigen-stimulated culture/counts per minute observed in medium control (definition of positive response: SI ≥ 2).

(ii) Guinea pigs.

PBMC were isolated from heparinized blood and purified by Histopaque-1090 gradient centrifugation for 45 min at 840 × g. Histopaque-1090 was prepared by mixing 68.4 ml of Histopaque-1077 with 31.6 ml of Histopaque-1119. PBMC were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% FCS, nonessential amino acids, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). PBMC were cultured in triplicate at 2 × 105 cells/well for 5 days at 37°C and 5% CO2 in flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (Life Technologies) in the presence of antigen and radiolabeled during the final 18 h of culture with [3H]thymidine (37 kBq/well; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The cultures were harvested onto glass fiber filters. Results were expressed as SI (definition of positive response: SI ≥ 2).

Bioinformatics.

The protein sequences of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv antigens discussed in this work were obtained from the TubercuList database (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/). Prediction of human HLA-DR-restricted determinants within these antigens was performed using the ProPred computer program (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred) (41).

RESULTS

ESAT-6-derived synthetic peptides are recognized across mammalian species.

Eleven synthetic peptides derived from the sequence of the M. tuberculosis-M. bovis protein ESAT-6 (16 amino acid residues long, overlapping by eight residues) were incubated with PBMC from 14 experimentally M. bovis-infected cattle, and their ability to stimulate IFN-γ responses was assessed by ELISPOT assays. The animals were obtained from four different farms and comprised several different breeds and crossbreeds of cattle (Holstein-Friesian, Limousin, Angus, or crosses thereof). We were therefore confident that we were testing animals with heterogeneous BoLA class II genotypes. As our modus operandi, we defined peptides that were recognized by more than 50% of the cattle tested as being “BoLA promiscuous.” As the results in Fig. 1A show, 6 of 11 of the tested peptides fell into this category (peptides 1, 3, 7, 8, 9, and 11). As expected, the responding cells belonged to the CD4+-T-cell subset (data not shown). Short-term T-cell lines raised against peptides 8 or 9 from two animals did not recognize peptides 7 and 9 or peptides 8 and 10, respectively, suggesting that separate nonoverlapping epitopes reside within peptides 7, 8, or 9 (data not shown).

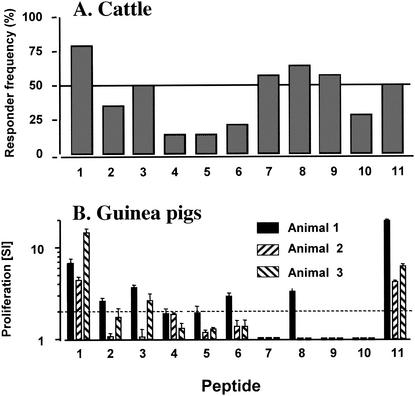

FIG. 1.

Identification of peptides from ESAT-6 recognized frequently by cattle and guinea pig T cells. (A) The ability of 11 ESAT-6-derived overlapping peptides to induce IFN-γ production by PBMC from 14 experimentally M. bovis-infected cattle was determined by ELISPOT assay. Results are expressed as a percentage (responder frequency) of animals producing IFN-γ (measured by ELISPOT assay) after peptide stimulation (tested at 20 μg/ml). Definition of responders: SFC with peptide − SFC without peptide ≥ 10, and SFC with peptide/SFC without peptide ≥ 2, where SFC is the number of spot-forming cells. The horizontal line indicates the cutoff for our definition of frequently (promiscuously) recognized peptides (50% responder frequency). (B) Proliferative responses of PBMC form three M. bovis-infected outbred guinea pigs to stimulation with ESAT-6-derived peptides (tested at 20 μg/ml). Positive response: SI (cpm with peptide/cpm without peptide) ≥ 2 (indicated by dashed horizontal line).

Since guinea pigs are the small-animal model of choice to test both novel TB vaccines and the potency of diagnostic skin test reagents, we decided to identify the T-cell determinants within ESAT-6 that are recognized by M. bovis-infected outbred guinea pigs. PBMC were prepared from infected animals and incubated with the ESAT-6-derived peptides described above. Two peptides were strongly recognized by all three guinea pigs tested (peptides 1 and 11, Fig. 1B), while PBMC from one animal also responded weakly to stimulation with peptides 2, 3, 6, and 8 (Fig. 1B). When we compared the recognition of ESAT-6-derived peptides by bovine- and guinea pig-derived T cells, we noted a specificity overlap in that both the N-terminal and C-terminal peptides (peptides 1 and 11, respectively) were strongly recognized by both species. Interestingly, the single epitope recognized by T cells after M. bovis infection of C57/BL10 (H-2b) and C57BL/10.D2 (H-2d) mice was also located within peptide 1, whereas the single epitope recognized by T cells from C57BL/10.BR (H-2k) was localized within peptide 8 (data not shown). Splenocytes from noninfected mice did not respond to any of these peptides (data not shown).

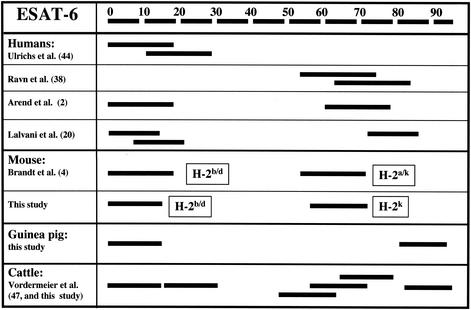

ESAT-6 is a major human and murine T-cell target antigen during tuberculous infections, and its determinants recognized by T cells from human TB patients and from M. tuberculosis-infected mice have been described. Comparing these published reports with the experimental data described in the present study allowed us to assess whether cross-species T-cell promiscuity existed across all four of these mammalian species. The results of this evaluation are shown in Fig. 2, where we have graphically represented the ESAT-6-derived epitopes frequently recognized by human, murine, bovine, and guinea pig T cells. Significantly, the N terminus of ESAT-6 was recognized across all four mammalian species (residues 1 to 16). In addition, we also observed a region towards the C terminus that was recognized by humans, bovine, and murine T cells (around amino acid residues 52 to 72).

FIG. 2.

Hierarchy of ESAT-6 epitope recognition in humans, cattle, mice, and guinea pigs. The positions of the most frequently recognized immunodominant peptide determinants described are shown (2, 4, 20, 38, 44, 47). Presented are peptides recognized by PBMC from ≥50% of human TB patients and M. bovis-infected cattle tested, the majority of M. bovis-infected outbred guinea pigs tested, and of T cells from the mouse inbred strains with the H-2 haplotypes indicated that were infected with either M. bovis or M. tuberculosis.

A program predicting human HLA-DR-binding determinants can predict BoLA class II-restricted epitopes.

In silico approaches to the prediction of bovine class II-restricted determinants are not yet available. However, based on the observations of cross-species recognition of nearly identical sequence regions of ESAT-6, in particular by human and bovine T cells, we postulated that algorithms predicting human T-cell determinants might also predict peptides recognized by bovine T cells. We chose to explore this notion by applying the ProPred prediction program that predicts human HLA-DR-restricted epitopes on the basis of virtual matrices to the prediction of bovine class II-restricted epitopes. The ESAT-6-derived epitopes predicted in this way were compared with the peptides frequently recognized by M. bovis-infected cattle described in Fig. 1. A high degree of agreement was observed between the positions of epitopes predicted to be recognized in the context of human HLA-DR and peptides actually recognized frequently by bovine T cells, i.e., four of six of these ESAT-6-derived peptides contained predicted determinants (data not shown). Single epitopes were predicted in two of six of the empirically defined peptides, while two predicted motifs were located each in two of six of these peptides (data not shown).

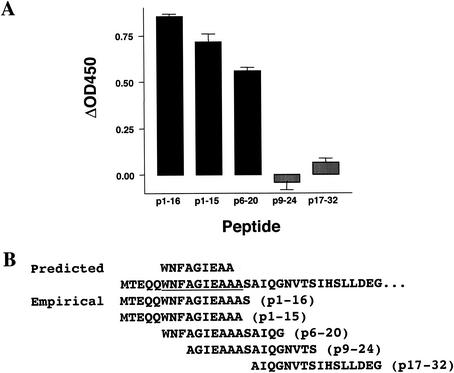

We next investigated whether the ProPred predicted sequences overlapped exactly with epitopes recognized by bovine lymphocytes by experimentally defining the minimal epitope recognized within ESAT-6 peptide 1 (residues 1 to 16). A short-term T-cell line from an M. bovis-infected calf responding to peptide 1 was established by stimulating its PBMC with this peptide. This T-cell line was then tested with four overlapping peptides covering the sequence from position 1 to 24; a peptide adjacent to the sequence region of peptide 1 was used as negative control (p17-32). The results of this experiment are shown in Fig. 3A. Peptides p1-16, p1-15, and p6-20 induced strong IFN-γ responses, whereas peptide p9-24 (and the negative control peptide p17-32) did not. This allowed us to define the epitope in p1 to be located within residues 6 and 15 (WNFAGIEAAA) (Fig. 3). The minimal epitope structure within p1 almost completely overlapped with the ProPred predicted sequence within p1 (WNFAGIEAA) (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Prediction of epitope recognized by bovine CD4+ T cells. (A) An ESAT-6 peptide 1 (residues 1 to 16) specific short-term T-cell line-derived from an M. bovis-infected calf was incubated with the overlapping peptides (tested at 20 μg/ml) indicated, and the production of IFN-γ after 4 days of culture was established. (B) The location of the experimentally defined epitope is shown in relation to the predicted sequence.

The next objective was to establish whether ProPred motifs were also located in nine other mycobacterial antigens whose immunodominant peptides had been determined experimentally in M. bovis-infected cattle. Data from eight of these were collated from the published literature; the determinants of another antigen, TB10.4, were identified in our laboratory during this study using a complete set of overlapping peptides (20-mer peptides; overlap, 12 residues [data not shown]). The same operational criteria as for ESAT-6 were applied to define immunodominance (i.e., peptides had to be recognized by ≥50% of cattle tested). The results of this analysis are compiled in Table 1. In total, 22 of 30 of the experimentally identified peptides (73.3% overall; 50 to 100% of the determinants defined in individual proteins) contained ProPred motifs. Sixty-seven peptides containing ProPred motifs were unlikely to have caused T-cell stimulation, which is a significant improvement on empirical screening using overlapping peptides, where 158 failed to induce T-cell stimulation (chi-square, P < 0.05; odds ratio, 1.73).

TABLE 1.

Efficiency of predicting bovine BoLA class II promiscuous peptides from mycobacterial antigens with ProPred

| Antigen | Rv desig- nationa | No. of peptides experimentally definedb | No. (%) of peptides contain- ing predicted epitopesc | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESAT-6 | Rv3875 | 6 | 4 (66) | 48, 47, this study |

| CFP-10 | Rv3874 | 5 | 4 (80) | 49 |

| MPB83 | Rv2873 | 1 | 1 (100) | 47 |

| MPB70 | Rv2875 | 2 | 2 (100) | 22 |

| MPB59 | Rv1886c | 2 | 2 (100) | 23 |

| MPB64 | Rv1980c | 2 | 1 (50) | 22 |

| MPB57 | Rv3418c | 1 | 1 (100) | 35 |

| 19 kDa | Rv3763 | 2 | 1 (50) | 35 |

| 38 kDa | Rv0934 | 3 | 2 (66) | 36 |

| TB10.4 | Rv0288 | 6 | 4 (66) | This study |

| Total | 30 | 22 (73.3) |

Prediction of peptide determinants from Rv3019c.

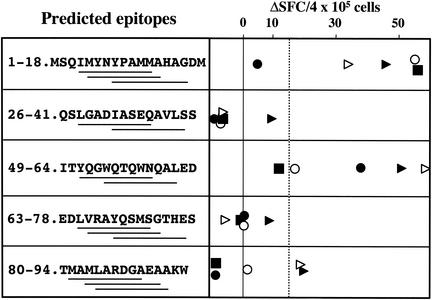

The retrospective analysis of published promiscuous peptides described above suggested that almost three-quarters of these peptides contained ProPred motifs (Table 1). We therefore set out to determine whether this finding could be applied to predict immunogenic peptides within other mycobacterial proteins. We selected RV3019c, because our preliminary results indicated that it induced strong IFN-γ responses in M. bovis-infected cows when tested as recombinant protein (data not shown). Five peptides were selected and synthesized on the basis that they contained at least two ProPred motifs each (Fig. 4). These peptides were tested in vitro using PBMC isolated from five infected calves that had previously responded to recombinant Rv3019c protein (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4, two of these peptides were recognized by four of five calves tested, while one more peptide induced IFN-γ responses in two of five animals.

FIG. 4.

Identification of determinants from Rv3019c recognized by PBMC from M. bovis-infected cattle. The ability of five peptides (tested at 25 μg/ml) predicted to contain two to three ProPred motifs (underlined sequence regions) to induce IFN-γ production by PBMC from five experimentally M. bovis-infected cattle was determined by ELISPOT. Data are expressed as ΔSFC, calculated as SFC with peptide − SFC without peptide, where SFC is the number of spot-forming cells; each symbol represents responses of one animal to the indicated peptide. Cutoff for positive responses (mean ΔSFC plus 3 × standard deviation when noninfected animals were tested with peptides [shown as a vertical dotted line): ΔSFC > 15.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have demonstrated overlaps in the recognition of some ESAT-6-derived determinants by T cells from four different mammalian species. Such overlaps between the repertoires of, e.g., human and murine T cells have been described before in the case of mycobacterial antigens (reviewed in reference 45). However, this is, to our knowledge, the first report comparing T-cell specificity towards mycobacterial antigens in two natural hosts of TB (humans and cattle) as well as in the two main small-animal models of this disease (guinea pigs and mice). This overlap between ESAT-6 determinants recognized by bovine and human CD4+ T cells led us to the hypothesis that programs predicting epitopes recognized by human T cells could also predict a proportion of those recognized by bovine T cells. We chose to explore this notion by using the virtual-matrix-based prediction program ProPred (41) because it covered a large number of human HLA-DR alleles (51 alleles) and therefore allowed a comprehensive analysis. In addition, ProPred is freely available electronically(http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred). This program is based partially on the original matrix-based computer program TEPITOPE (43), which has been used several times recently to correctly predict promiscuous human DR-restricted epitopes not only in melanoma cell antigens (8, 26), and allergens (13) but also in the M. tuberculosis antigen Mce (34).

BoLA-DR and HLA-DR are structurally related orthologous loci and both DRA and DRB genes were relatively quickly identified due to their sequence similarities with HLA-DR (reviewed in reference 14). We therefore felt justified in attempting to predict bovine epitopes using a computer program targeted at human HLA-DR. Nevertheless, we also had to make assumptions that were not supported by our data and we were somewhat surprised by the success of ProPred to correctly predict the presence of HLA-DR-restricted motifs in a high percentage of peptides recognized by bovine T cells. One assumption that we had to make was that the majority of determinants that we analyzed were associated with bovine DR. In humans most antigen-specific peripheral blood-derived CD4+ T cells, and in particular those specific for mycobacterial antigens, have been found to be HLA-DR restricted (25, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33). However, both BoLA-DR- and DQ-restricted responses to, e.g., foot-and-mouth disease virus antigens have been reported (16, 17), and one cannot a priori assume that the mycobacterial determinants discussed in the present study were mainly BoLA-DR restricted. However, due to the complexity of the bovine restriction element usage, it is difficult to link particular T-cell responses to specific restriction elements, and to attempt this was beyond the scope our analysis. It is conceivable that some of the 27% of experimentally defined bovine epitopes not carrying ProPred motifs (Table 1) were BoLA-DQ restricted. However, when we compared the sequences of these peptides no obvious common sequence characteristics were found (data not shown).

Using overlapping peptide analysis we were able to demonstrate that the ProPred predicted epitope sequence overlap with the actual bovine epitopes mapped within the N-terminal peptide of ESAT-6. However, more studies defining further epitopes recognized by bovine CD4+ T cells have to be performed to establish clearly the overall efficacy of ProPred to predict actual bovine epitopes. We therefore refer throughout the text of this manuscript to ProPred motifs within peptides recognized frequently by bovine T cells and not to actual epitopes (with the exception of the p1 epitopes that we have defined in this study). Interestingly, a recent study has defined 12 bovine DRB3*2002- and DRB380701-restricted peptides from two bovine viral diarrhea virus proteins (11). When we analyzed these proteins with ProPred we found the presence of between 1 and 5 motifs in 11 of 12 of these 18-mer BoLA-DR-restricted peptides. Furthermore, ProPred motifs overlapped strikingly with eight of twelve of the minimal epitopic stimulatory sequences (9 to 17 residues long) that this study defined within these peptides (11) (six of seven of DRB3*0701- and 2/5 of DRB3*2002-restricted epitopes). Superimposing the predicted motifs over these minimal sequences and the N-terminal ESAT-6 epitope that we defined in Fig. 3 allowed us to conclude that, at least at position 1 of these epitopes, highly overlapping sets of anchor residues (either L, V, I, M, or W, respectively; data not shown) interact with pocket 1 of bovine DR molecules. This is in line with the described presence of a hydrophobic anchor residue at this position in the overall majority of human and murine class II ligands (reviewed in reference 37).

In recent years we and others have used synthetic peptides not only as diagnostic reagents for the differential diagnosis of BCG-vaccinated and M. bovis-infected cattle (47, 48, 49) but also as rapid screening reagents to identify novel immunogenic antigens (9, 28). For this purpose, we prepared sets of overlapping peptides from candidate antigens identified by comparative genome analysis (e.g., using the published M. tuberculosis genome [10]). These peptides were then tested as pools of 10 to 20 individual peptides (9, 28). This approach requires large numbers of peptides and results in high production costs. However, ProPred prescreening of antigens could reduce the number of peptides that have to be synthesized. For example, to identify the 30 empirically defined peptides listed in Table 1, 188 peptides were needed. This number would have fallen to 89 if one had prepared only peptides carrying predicted motifs. Therefore, we envisage that the advantages of using ProPred to predict cattle determinants will be best realized by reducing the numbers of peptides required by concentrating on pools containing only peptides with predicted motifs rather than screening pools of fully overlapping peptides.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) of Great Britain.

We express our appreciation to the staff of the Animal Services Unit at the VLA for their dedication to animal welfare. We also thank Shelley Rhodes for critical and helpful comments.

Editor: S. H. E Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Altuvia, Y., O. Schueler, and H. Margalit. 1995. Ranking potential binding peptides to MHC molecules by a computational threading approach. J. Mol. Biol. 249:244-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arend, S. M., A. Geluk, K. E. Van Meijgaarden, J. T. Van Dissel, M. Theisen, P. Andersen, and T. H. M. Ottenhoff. 2000. Antigenic equivalence of human T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis specific RD1-encoded protein antigens ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10 and to mixtures of synthetic peptides. Infect. Immun. 68:3314-3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berggren, S. A. 1981. Field experiment with BCG vaccine in Malawi. Br. Vet. J. 137:88-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt, L., T. Oettinger, A. Holm, A. B. Andersen, and P. Andersen. 1996. Key epitopes on the ESAT-6 antigen recognized in mice during the recall of protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 157:3527-3533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buddle, B., N. A. Parlane, D. L. Keen, F. E. Aldwell, J. M. Pollock, K. Lightbody, and P. Andersen. 1999. Differentiation between Mycobacterium bovis BCG-vaccinated and M. bovis infected cattle using recombinant mycobacterial antigens. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buddle, B. M., G. W. de Lisle, A. Pfeffer, and F. E. Aldwell. 1995. Immunological responses and protection against Mycobacterium bovis in calves vaccinated with a low dose of BCG. Vaccine 13:1123-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buddle, B. M., D. Keen, A. Thomson, G. Jowett, A. R. McCarthy, J. Heslop, G. W. De Lisle, J. L. Stanford, and F. E. Aldwell. 1995. Protection of cattle from bovine tuberculosis by vaccination with BCG by the respiratory or subcutaneous route, but not by vaccination with killed Mycobacterium vaccae. Res. Vet. Sci. 59:10-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cochlovius, B., M. Stassar, O. Christ, L. Raddrizzani, J. Hammer, I. Mytilineos, and M. Zoller. 2000. In vitro and in vivo induction of a Th cell response toward peptides of the melanoma-associated glycoprotein 100 protein selected by the TEPITOPE program. J. Immunol. 165:4731-4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cockle, P. C., S. V. Gordon, A. Lalvani, B. Buddle, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2002. Identification of novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens with potential as diagnostic reagents or subunit vaccine candidates by comparative genomics. Infect. Immun. 70:6996-7003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry, 3rd, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, B. G. Barrell, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collen, T., V. Carr, K. Parsons, B. Charleston, and W. I. Morrison. 2002. Analysis of the repertoire of cattle CD4 T cells reactive with bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 87:235-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Groot, A. S., B. M. Jesdale, E. Szu, J. R. Schafer, R. M. Chicz, and G. Deocampo. 1997. An interactive Web site providing major histocompatibility ligand predictions: application to HIV research. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 13:529-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lalla, C., T. Sturniolo, L. Abbruzzese, J. Hammer, A. Sidoli, F. Sinigaglia, and P. Panina-Bordignon. 1999. Cutting edge: identification of novel T cell epitopes in Lol p5a by computational prediction. J. Immunol. 163:1725-1729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis, S. A., and K. T. Ballingall. 1999. Cattle MHC: evolution in action? Immunol. Rev. 167:159-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flynn, J. L., and J. Chan. 2001. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:93-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Briones, M. M., G. C. Russell, R. A. Oliver, C. Tami, O. Taboga, E. Carrillo, E. L. Palma, F. Sobrino, and E. J. Glass. 2001. Association of bovine DRB3 alleles with immune response to FMDV peptides and protection against viral challenge. Vaccine 19:1167-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass, E. J., R. A. Oliver, and G. C. Russell. 2000. Duplicated DQ haplotypes increase the complexity of restriction element usage in cattle. J. Immunol. 165:134-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer, J., E. Bono, F. Gallazzi, C. Belunis, Z. Nagy, and F. Sinigaglia. 1994. Precise prediction of major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide interaction based on peptide side chain scanning. J. Exp. Med. 180:2353-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honeyman, M. C., V. Brusic, N. L. Stone, and L. C. Harrison. 1998. Neural network-based prediction of candidate T-cell epitopes. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:966-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalvani, A., A. A. Pathan, H. McShane, R. J. Wilkinson, M. Latif, C. P. Conlon, G. Pasvol, and A. V. Hill. 2001. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by enumeration of antigen-specific T cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 163:824-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewin, H. A., G. C. Russell, and E. J. Glass. 1999. Comparative organization and function of the major histocompatibility complex of domesticated cattle. Immunol. Rev. 167:145-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lightbody, K. A., R. M. Girvin, D. P. Mackie, S. D. Neill, and J. M. Pollock. 1998. T-cell recognition of mycobacterial proteins MPB70 and MPB64 in cattle immunized with antigen and infected with Mycobacterium bovis. Scand. J. Immunol. 48:44-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lightbody, K. A., R. M. Girvin, D. A. Pollock, D. P. Mackie, S. D. Neill, and J. M. Pollock. 1998. Recognition of a common mycobacterial T-cell epitope in MPB59 of Mycobacterium bovis. Immunology 93:314-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipford, G. B., M. Hoffman, H. Wagner, and K. Heeg. 1993. Primary in vivo responses to ovalbumin. Probing the predictive value of the Kb binding motif. J. Immunol. 150:1212-1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundin, K. E. A., L. M. Solid, and E. Throsby. 1996. Class-II restricted T cell function, p. 329. In M. J. Browning and A. J. McMicael (ed.), HLA and MHC: gene, molecules and function. BIOS Scientific, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 26.Manici, S., T. Sturniolo, M. A. Imro, J. Hammer, F. Sinigaglia, C. Noppen, G. Spagnoli, B. Mazzi, M. Bellone, P. Dellabona, and M. P. Protti. 1999. Melanoma cells present a MAGE-3 epitope to CD4+ cytotoxic T cells in association with histocompatibility leukocyte antigen DR11. J. Exp. Med. 189:871-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meister, G. E., C. G. Roberts, J. A. Berzofsky, and A. S. De Groot. 1995. Two novel T cell epitope prediction algorithms based on MHC-binding motifs; comparison of predicted and published epitopes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and HIV protein sequences. Vaccine 13:581-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustafa, A. S., P. C. Cockle, F. Shaban, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2002. Immunogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RD1 region gene products in infected cattle. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 130:37-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustafa, A. S., K. E. Lundin, R. H. Meloen, T. M. Shinnick, and F. Oftung. 1999. Identification of promiscuous epitopes from the Mycobacterial 65-kilodalton heat shock protein recognized by human CD4+ T cells of the Mycobacterium leprae memory repertoire. Infect. Immun. 67:5683-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustafa, A. S., K. E. Lundin, and F. Oftung. 1993. Human T cells recognize mycobacterial heat shock proteins in the context of multiple HLA-DR molecules: studies with healthy subjects vaccinated with Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium leprae. Infect. Immun. 61:5294-5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mustafa, A. S., F. A. Shaban, A. T. Abal, R. Al-Attiyah, H. G. Wiker, K. E. Lundin, F. Oftung, and K. Huygen. 2000. Identification and HLA restriction of naturally derived Th1-cell epitopes from the secreted Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85B recognized by antigen-specific human CD4+ T-cell lines. Infect. Immun. 68:3933-3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oftung, F., A. Geluk, K. E. Lundin, R. H. Meloen, J. E. Thole, A. S. Mustafa, and T. H. Ottenhoff. 1994. Mapping of multiple HLA class II-restricted T-cell epitopes of the mycobacterial 70-kilodalton heat shock protein. Infect. Immun. 62:5411-5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ottenhoff, T. H., S. Neuteboom, D. G. Elferink, and R. R. de Vries. 1986. Molecular localization and polymorphism of HLA class II restriction determinants defined by Mycobacterium leprae-reactive helper T cell clones from leprosy patients. J. Exp. Med. 164:1923-1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panigada, M., T. Sturniolo, G. Besozzi, M. G. Boccieri, F. Sinigaglia, G. G. Grassi, and F. Grassi. 2002. Identification of a promiscuous T-cell epitope in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mce proteins. Infect. Immun. 70:79-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollock, J. M., A. J. Douglas, D. P. Mackie, and S. D. Neill. 1994. Identification of bovine T-cell epitopes for three Mycobacterium bovis antigens: MPB70, 19,000 MW and MPB57. Immunology 82:9-15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollock, J. M., A. J. Douglas, D. P. Mackie, and S. D. Neill. 1995. Peptide mapping of bovine T-cell epitopes for the 38 kDa tuberculosis antigen. Scand. J. Immunol. 41:85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rammensee, H. G., T. Friede, and S. Stevanoviic. 1995. MHC ligands and peptide motifs: first listing. Immunogenetics 41:178-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravn, P., A. Demissie, T. Eguale, H. Wondwosson, D. Lein, H. A. Amoudy, A. S. Mustafa, A. K. Jensen, A. Holm, I. Rosenkrands, F. Oftung, J. Olobo, F. von Reyn, and P. Andersen. 1999. Human T cell responses to the ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 179:637-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rotzschke, O., K. Falk, S. Stevanovic, G. Jung, P. Walden, and H. G. Rammensee. 1991. Exact prediction of a natural T cell epitope. Eur. J. Immunol. 21:2891-2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sette, A., J. Sidney, C. Oseroff, M. F. del Guercio, S. Southwood, T. Arrhenius, M. F. Powell, S. M. Colon, F. C. Gaeta, and H. M. Grey. 1993. HLA DR4w4-binding motifs illustrate the biochemical basis of degeneracy and specificity in peptide-DR interactions. J. Immunol. 151:3163-3170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh, H., and G. P. Raghava. 2001. ProPred: prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics 17:1236-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stassar, M. J., L. Raddrizzani, J. Hammer, and M. Zoller. 2001. T-helper cell-response to MHC class II-binding peptides of the renal cell carcinoma-associated antigen RAGE-1. Immunobiology 203:743-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sturniolo, T., E. Bono, J. Ding, L. Raddrizzani, O. Tuereci, U. Sahin, M. Braxenthaler, F. Gallazzi, M. P. Protti, F. Sinigaglia, and J. Hammer. 1999. Generation of tissue-specific and promiscuous HLA ligand databases using DNA microarrays and virtual HLA class II matrices. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:555-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ulrichs, T., M. E. Munk, H. Mollenkopf, S. Behr-Perst, R. Colangeli, M. L. Gennaro, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1998. Differential T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT6 in tuberculosis patients and healthy donors. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:3949-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vordermeier, H. M. 1995. T-cell recognition of mycobacterial antigens. Eur. Respir. J. Suppl. 20:657s-667s. [PubMed]

- 46.Vordermeier, H. M., M. A. Chambers, P. C. Cockle, A. O. Whelan, and R. G. Hewinson. 2002. Correlation of ESAT-6 specific IFN-γ production with pathology in cattle following BCG vaccination against experimental bovine tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70:3026-3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vordermeier, H. M., P. C. Cockle, A. Whelan, S. Rhodes, and R. G. Hewinson. 2000. Towards the development of diagnostic assays to discriminate between Mycobacterium bovis infection and BCG vaccination in cattle. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:S291-S298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vordermeier, H. M., P. C. Cockle, A. Whelan, S. Rhodes, N. Palmer, D. Bakker, and R. G. Hewinson. 1999. Development of diagnostic reagents to differentiate between Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination and M. bovis infection in cattle. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:675-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vordermeier, H. M., A. Whelan, P. J. Cockle, L. Farrant, N. Palmer, and R. G. Hewinson. 2001. Use of synthetic peptides derived from the antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 for differential diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis in cattle. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:571-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wood, P. R., and J. S. Rothel. 1994. In vitro immunodiagnostic assays for bovine tuberculosis. Vet. Microbiol. 40:125-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]