Abstract

We studied a Cryptococcus neoformans strain that caused feline chronic nasal granuloma without disseminated disease. This strain, B-4551, grows at temperatures up to 35°C and fails to cause systemic infection in mice. Many cells of B-4551 formed short hyphal elements in feline nasal tissue and occasionally at 35°C in vitro. A complementation and sequence analysis revealed that the temperature-sensitive (Ts) phenotype of B-4551 was due to deletion of a lysine residue in the cryptococcal CCN1 gene. B-4551 complemented with the wild type CCN1 gene grew at 37°C and caused fatal systemic infection in mice. The CCN1 gene encodes a protein containing 16 copies of a tetratricopeptide repeat. CCN1 is homologous to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CLF1 gene, which is required for pre-mRNA splicing, cell cycle progression, and DNA replication, and to the Drosophila melanogaster crn gene, which is involved in neurogenesis. CLF1 complemented the Ts phenotype of B-4551. CCN1, however, failed to rescue the clf1 mutant in S. cerevisiae. These results indicate that the Ccn1p may not be as functionally diverse as Clf1p in yeast.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an opportunistic pathogen that causes serious systemic infection primarily in immunocompromised patients (17). Among the major virulence factors identified (4, 5, 6, 8, 18, 26), the ability to grow at 37°C (19, 24) appears to be the most important feature that separates C. neoformans from other species of the genus Cryptococcus. C. neoformans is the only member of the genus Cryptococcus that grows well at 37°C and that causes serious systemic disease. Indeed, in order to cause systemic infection in warm-blooded hosts, microorganisms require the ability to grow at temperatures equal to or higher than 37°C. Although strains of C. neoformans that grow poorly at 37°C have been known (17), isolates from human or animal infection that completely fail to grow at 37°C have never been reported until recently. In 2000, Bemis et al. (2) reported a strain of C. neoformans (B-4551), from a localized chronic granulomatous lesion in the nasal cavity of a cat, growing at temperatures up to 35°C but not at 37°C. Unlike typical cryptococcosis cases, histological sections of the nasal tissue showed many yeast cells with hyphal elements resembling germ tube formation. These hyphal elements were also occasionally observed among the cells grown on mycological agar medium at 35°C but not at 30°C (2).

Identification of the genetic defect(s) in such a strain should unveil factors necessary for C. neoformans to grow at 37°C and cause systemic infection in warm-blooded hosts. There have been several studies concerning C. neoformans gene defects that result in temperature sensitivity and, in turn, loss of virulence in experimental animals. Disruption of the calcineurin A gene (CNA1) caused a temperature-sensitive (Ts) phenotype in C. neoformans consisting of impaired growth at 37°C and a lack of viability at 39°C (24). Upon reintroduction of wild-type CNA1, temperature tolerance and virulence were restored (24). When the RAS1 gene is disrupted in C. neoformans, the resulting mutant is viable but fails to grow at 37°C. Consequently, ras1 strains are avirulent (1).

We have identified the genetic lesion in the CCN1 (cryptococcal crooked neck 1) gene that is responsible for the Ts phenotype and formation of hyphal elements at 35°C in the cat isolate B-4551. The CCN1 gene encodes a protein containing 16 tandem copies of a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) which consists of 34 loosely conserved amino acid residues. TPR-bearing proteins are found in animals, plants, and microorganisms and function in multiple cellular processes such as transcription, peroxisome biogenesis, cell cycle progression, and pre-mRNA splicing (reviewed in references 13 and 21). The CCN1 gene shows high sequence homology to two known essential genes, CLF1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and crn of Drosophila melanogaster. The CLF1 gene encodes a protein required for pre-mRNA 5′ splice site cleavage (9). A lack of Clf1p arrests spliceosome assembly after U2 snRNP (small nuclear ribonuclear protein particle) addition and prior to U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP association (9). Interestingly, CLF1 also plays a role in cell cycle progression. When CLF1 expression was repressed, the cell cycle was arrested at G2 phase (25) and the entry into S phase was also delayed (31), indicating that the CLF1 gene may function at multiple stages of the cell cycle. The crn gene of Drosophila is involved in neurogenesis, and the loss of zygotic Crnp causes defects in proliferation of brain neuroblasts (30). crn mutants die during early embryogenesis with a variety of morphological defects including muscle and central nervous system impairments (30). The level of DNA synthesis is reduced in crn mutants; thus, the crn gene was also suggested to contribute to cell cycle progression (30). Meanwhile, Burnette and colleagues showed that, in crn heterozygous mutants, alternative splicing of the Ubx (ultrabithorax) mI exon was significantly reduced, suggesting that crn functions in Ubx RNA splicing (3).

We demonstrate here that complementation of strain B-4551 with the wild-type CCN1 gene results in the production of typical yeast morphology at 35 and 37°C. The complemented strain, ST1-4551, gained the ability to cause systemic fatal infection in mice. The CLF1 gene alleviated the temperature sensitivity in strain B-4551 and restored normal yeast morphology, but CCN1 failed to rescue the clf1-null allele, suggesting functional discrepancy between these two homologous genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and media.

B-4551 is a serotype A, MATα strain of C. neoformans that was isolated from a chronic granulomatous lesion in the nasal cavity of a cat (2). B-4551FOA is a uracil-requiring (ura5) strain isolated by plating B-4551 on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) medium (20). H99 is a C. neoformans serotype A clinical strain (24). All strains were maintained on yeast extract-peptone-glucose (YEPD) agar (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% glucose, 2% agar). YNB agar is a minimal medium containing, per liter, 6.7 g of yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), 20 g of glucose, and 20 g of agar.

Library construction and transformation.

Total genomic DNA isolated from strain H99 was partially digested with Sau3AI. Restriction fragments greater than 6 kb were gel isolated and inserted into the BamHI site of pPM8 (22). This construct was transformed into Escherichia coli strain HB101 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Transformants were screened on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing 20 μg of kanamycin/ml and 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. For transformation of C. neoformans, exponentially growing cells were transformed with linearized plasmid DNAs by the electroporation method (29).

Southern blot analysis.

Genomic DNAs were extracted from the selected transformants, electrophoresed on 0.8% agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and then hybridized with radiolabeled ([32P]dCTP; Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) probes at 65°C.

Recovery of plasmid DNAs from C. neoformans transformants.

To recover plasmid DNAs from C. neoformans, total DNAs were isolated from C. neoformans transformants, digested with NotI to remove the telomeric sequences present in the episomal plasmids (22), and ligated. This DNA was transformed into E. coli by electroporation. Strain B-4551 was transformed with the rescued plasmid, pPM22, but the transformants grew more slowly at 37°C than the original transformants. It was found that pPM22 had lost a 0.5-kb fragment containing the NotI site during the rescue process. The missing 0.5-kb BamHI-NotI fragment was amplified by PCR using total DNA of the transformant T1 clone as a template to construct pPM33. The 4-kb NotI-XbaI fragment excised from the rescued plasmid pPM22 and the 0.5-kb BamHI-NotI fragment of pPM33 were ligated and then inserted into the BamHI-XbaI sites of pCIP3 (12). We named this construct pPM34. The C. neoformans expression vector pYCC329 was constructed by inserting the blunt-ended 2.3-kb GAL7::GUS fragment isolated from plasmid pAUG-GUS (7) into the EcoRI/XbaI site of pPM8. Plasmids relevant to this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

List of plasmids relevant to this study

| Plasmid | Gene or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pCIP3 | URA5 | 27 |

| pPM8 | URA5 containing episomal cloning vector | 20 |

| pYCC329 | GAL7::GUS in pPM8 backbone | This study |

| pPM22 | Rescued plasmid from transformant T1 | This study |

| pPM33 | 0.5-kb NotI fragment in TOPO 2.1 | This study |

| pPM34a | 0.5-kb NotI fragment from pPM33 inserted into pPM22 | This study |

| pPM34 | 4.5-kb genomic DNA fragment containing the CCN1 gene in pCIP3 | This study |

| pPM35 | ccn1 carrying a deletion of the three nucleotides CAA (positions 859-861) | This study |

| pPM36 | ccn1 carrying a deletion as well as substitution mutations in the pPM34 backbone | This study |

| pSC3 | TEF::CCN1 (cDNA) | This study |

| pSC8 | GAL7p::CCN1 (cDNA) in pYCC329 backbone | This study |

| pSC9 | GAL7p::CLF1 in pYCC329 backbone | This study |

Sequencing of the dysfunctional ccn1 gene isolated from B-4551.

The genomic sequence of ccn1 from strain B-4551 was amplified by PCR with five sets of primers designed to produce five overlapping fragments spanning the 4-kb fragment (NotI-XbaI) of pPM22. All five fragments were cloned into the PCR2.1 TOPO vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and the sequences were confirmed by analyzing three independent clones from each construct. Plasmids pPM35 and pPM36 were constructed by swapping the mutated regions of ccn1 of B-4551 with pPM34 in order to detect the genetic lesions responsible for the Ts phenotype. Plasmid pPM35 contained ccn1 with a deletion of three nucleotides, CAA (nucleotides 859 to 861). Plasmid pPM36 contained ccn1 with three nucleotide substitutions (G at −324, T at −124, and G at 1173) and the deletion of CAA (nucleotides 859 to 861).

Plasmids used for complementation of the C. neoformans ccn1 mutation and the S. cerevisiae clf1 mutation.

To place the cDNAs of the CCN1 and CLF1 genes under the control of the C. neoformans GAL7 promoter, cDNAs of the CCN1 and CLF1 genes were each inserted into the BamHI/NdeI site of pYCC329, and the resulting constructs were named pSC8 and pSC9, respectively.

To construct TEF::CCN1 (pSC3), the CCN1 cDNA (2.3 kb) was inserted into the SpeI/PstI sites of plasmid vector TEF424 (23). A clf1 mutant strain of S. cerevisiae, SYC2 (MATα ura3 lys2 ade2 trp1 his3 leu2 clf1::HIS3), harboring the pBM150 rescue plasmid (with the URA3 GAL1::CLF1 insert) (9) was transformed with pSC3 and grown on selection medium with galactose as the sole carbon source. The resulting transformants were cultured on a medium with glucose as the sole carbon source in order to observe the complementation of the clf1 phenotype by TEF::CCN1.

Virulence study.

The murine systemic model was used to test the virulence of strains B-4551 and ST1-4551 as previously described (4). Male mice were injected with 0.2 ml of the yeast cell suspension (9 × 105 cells) in the lateral tail vein. Groups of 14 mice per strain were injected and then monitored for 70 days. Two mice from each group were sacrificed on days 22 and 81, and the fungal loads of various organs were determined. The fungal loads of the brain and other organs were determined by plating the organ homogenates on YEPD plates and counting the colonies after 4 days of incubation at 30°C.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number for the CCN1 sequence is AF265234.

RESULTS

Complementation of mutant phenotypes of B-4551.

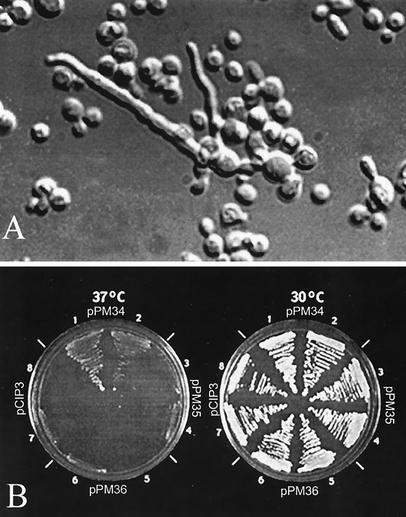

Strain B-4551 was identified as serotype A, MATα, melanin positive, and capsule positive, with the typical carbohydrate assimilation profile of C. neoformans (2). The growth of B-4551 at 30°C was normal, with typical yeast morphology (data not shown), while hyphal formation was observed among occasional cells grown at 35°C (Fig. 1A). To complement the mutant phenotype, a spontaneous ura5 mutant of B-4551 (B-4551FOA) was transformed with a genomic DNA library of H99. Of the105 transformants screened, 4 clones (T1, T2, T3, and T4) were observed to grow at 37°C. Retransformation of B-4551FOA with total DNA isolated from T1 and T4 complemented the Ts phenotype and the uracil requirement of B-4551FOA. Furthermore, the T1 and T4 clones became temperature sensitive and uracil auxotrophs as they lost the episomal plasmids by repeated transfers on YEPD medium. The plasmids rescued from T1 and T4 each contained a 6-kb insert with identical restriction enzyme digestion patterns (data not shown). Plasmid pPM22 (Fig. 2) recovered from the T1 clone was chosen for characterization of its insert. The growth rate of retransformants with recovered pPM22 was slightly lower than that of T1 or T4. We hypothesized that this was due to loss of some portion of the insert during the rescue process. In the rescue process, the DNA was digested with the NotI enzyme. We found that a 0.5-kb BamHI-NotI fragment from the 5′ end of the insert was lost (Fig. 2). The missing 0.5-kb fragment was amplified by PCR using total DNA isolated from transformant T1 as a template and was then inserted into the 5′ end of pPM22. We named this construct pPM34a. Several overlapping subclones of pPM34a were constructed and transformed into B-4551FOA. Plasmid pPM34 (Fig. 2) contained the 4.5-kb insert, required for complementation of the mutant phenotype. Transformants containing pPM34 grew normally at 37°C, though more slowly than at 30°C, as shown in Fig. 1B. These transformants also restored the normal yeast morphology at 35°C as well as at 37°C (data not shown). The optimum growth temperature of C. neoformans is 30 to 32°C (17).

FIG. 1.

(A) Yeast cells of B-4551 grown on YEPD agar at 35°C for 5 days, showing budding yeasts, elongated cells, and yeast cells with hyphal strands. (B) Complementation of the B-4551 Ts phenotype by different plasmid constructs. Two independent transformants were streaked onto minimal agar and incubated at 30 and 37°C. Only pPM34 complemented the Ts phenotype.

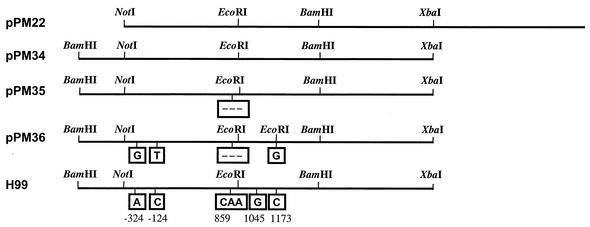

FIG. 2.

Restriction maps of the plasmids and the genomic CCN1 of H99. pPM35 contained a deletion of CAA (nucleotides 859 to 861). The CCN1 sequence of pPM36 contained three nucleotide substitutions (boxed) and deletions of CAA relative to the corresponding H99 sequence.

Characterization of the CCN1 gene.

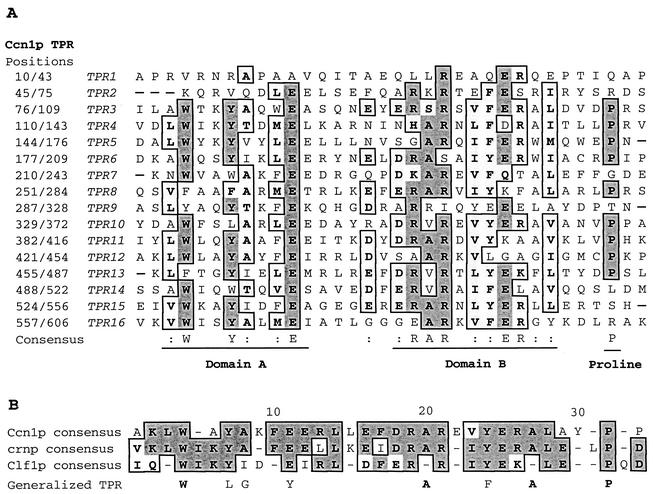

The DNA sequences of the pPM34 insert and its corresponding cDNA clones were determined. A sequence comparison of the genomic and coding regions revealed the presence of nine introns. The insert DNA of pPM34 encoded a protein of 724 amino acid residues (85 kDa). The predicted protein sequence exhibited high homology to the D. melanogaster Crnp protein (50% identity and 62% similarity) and the S. cerevisiae Clf1p protein (37% identity and 51% similarity). The D. melanogaster crn gene is known to be involved in neurogenesis (30) and alternative splicing (3). The CLF1 gene has been implicated in pre-mRNA splicing (9), cell cycle progression (25), and DNA replication in S. cerevisiae (31). Both Crnp and Clf1p are essential proteins and belong to the TPR protein family. Ccn1p contains 16 copies of the TPR (Fig. 3A), and alignment of the 16 TPR elements revealed a consensus sequence that matched well with those of Crnp and Clf1p (9, 30) (Fig. 3B). The highest degree of identity was found in three regions: domain A, domain B, and the proline at position 32 (Fig. 3A). Hybridization of pPM34 with H99 chromosomes resolved by contour-clamped homogeneous electric field (CHEF) indicated that the CCN1 gene is located on chromosome 1 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the Ccn1p TPR units. Sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTAL W (28). (A) The 16 TPR repeats in Ccn1p, showing the regions with 40 to 69% similarity (light shading) and those with >70% similarity (dark shading). (B) Alignment of the TPR consensus sequences of Ccn1p, Crnp, and Clf1p, and consensus TPR.

Determination of the genetic defects in ccn1 attributable to the mutant phenotype of B-4551.

Sequence comparison of the CCN1 genes of B-4551 and H99 revealed differences at seven positions in B-4551, five localized within the coding region and two within the promoter region (Fig. 2). Adenosine (nucleotide −324) was replaced with guanosine; cytosine (nucleotide −124) was replaced with thymine. Deletion of three successive nucleotides, CAA (nucleotides 859, 860, and 861), corresponding to the third nucleotide (C) of alanine (residue 216) and the first two nucleotides (AA) of the following lysine (residue 217), resulted in a deletion of lysine (residue 217) in TPR7. Since the nucleotide numbering includes intron sequences, nucleotides 859 to 861 correspond to amino acid residues 216 and 217. Replacement of guanosine (nucleotide 1045) with adenosine produced a silent mutation in alanine (residue 278), and the cytosine in the sixth intron (nucleotide 1173) was replaced with guanosine. To identify the regions responsible for the Ts phenotype, two kinds of mutations were introduced into the CCN1 gene of H99. The first construct, pPM36, contained all mutations except for the silent mutation in alanine (nucleotide 1045), and the second construct, pPM35, contained the three-nucleotide deletion (CAA at positions 859 to 861) of CCN1. These plasmids were transformed into B-4551FOA and tested for growth at 37°C. Unlike pPM34, neither pPM35 nor pPM36 complemented the Ts phenotype (Fig. 1B), indicating that the CAA deletion in TPR7 alone caused the Ts phenotype of B-4551.

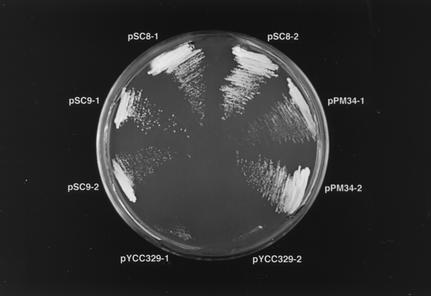

Complementation of the ccn1 phenotype with the S. cerevisiae CLF1 gene.

Since the CCN1 gene showed high sequence similarity to the S. cerevisiae CLF1 gene, we suspected that it was a functional homolog of the CLF1 gene. To address this issue, we tested whether CLF1 complemented the ccn1 mutation. Plasmid pSC9 was constructed by placing the CLF1 gene downstream of the GAL7 promoter in the C. neoformans expression vector pYCC329 and was transformed into B-4551FOA. The resulting transformants were transferred onto minimal agar containing galactose as the carbon source and were cultured at 37°C. The CLF1 gene complemented the Ts phenotype and morphological abnormality at 35°C, while the pYCC329 vector did not (Fig. 4). The growth rate of B-4551FOA complemented with pSC9 was comparable to that of the strain complemented with pPM34 (Fig. 4). We also tested whether cDNA of the CCN1 gene complemented the clf1-null allele in S. cerevisiae by transforming the SYC2 strain with pSC3 (see Materials and Methods). However, the CCN1 gene (pSC3) failed to complement the clf1 mutant strain. Transformants containing pSC3 did not grow on glucose medium (data not shown). The CCN1 cDNA was confirmed to be functional, since transformation of B-4551FOA with pSC8 not only complemented its mutant phenotype but also resulted in growth rates equal to those of the transformants with pPM34 which contained the CCN1 genomic sequence (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Growth of B-4551 transformants with pPM34, pSC8, or pSC9 at 37°C. Strain B-4551FOA was transformed with pPM34, pSC8, or pSC9, containing the wild-type CCN1 gene, the CCN1 cDNA, or the Saccharomyces CLF1 gene, respectively. Strain B-4551FOA transformed with the pYCC329 expression vector served as a negative control. Two independent transformants obtained with each plasmid were streaked onto galactose-based minimal agar and incubated at 37°C for 5 days.

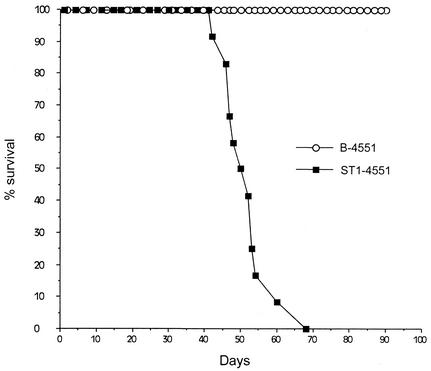

Virulence study.

Strain B-4551 was avirulent when it was introduced intravenously into mice (Fig. 5). Mice inoculated with B-4551 remained healthy 100 days postinjection, and no fungus was detected in either the brain or the testis on day 22 or in the brain, spleen, kidney, or testis on day 81. In contrast, B-4551 complemented with the CCN1 gene (ST1-4551) produced fatal infections in 100% of the mice within 68 days. In mice infected with strain ST1-4551, fungal loads of organs on day 22 were 4 × 104 and 3 × 103 yeast cells for the brain and testis, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Survival of mice infected with 9 × 105 yeast cells of B-4551 or ST1-4551. ST1-4551 is a stable transformant of B-4551FOA complemented with pPM34, containing the wild-type CCN1 gene.

DISCUSSION

An isolate of C. neoformans (B-4551) that produced a chronic granulomatous lesion in the nasal cavity of a cat was previously reported to be temperature sensitive at 37°C (2). Since strains of C. neoformans that fail to grow at 37°C and yet cause infection in warm-blooded animals have not been studied before, we attempted to characterize the genetic defect in strain B-4551. By complementation of the mutation in B-4551 with a genomic library of H99, we identified the cryptococcal CCN1 gene, which encodes a protein of 724 amino acid residues bearing 16 copies of TPR. TPR is composed of 34 loosely conserved amino acid residues and is believed to mediate protein-protein interactions (13, 21). Alignment of the 16 TPR elements of CCN1 revealed two highly conserved subdomains, A and B, and a proline at position 32. Proline 32, present at the carboxyl end of domain B, is known to induce turns between the two α-helices. According to the crystal structure of protein phosphatase 5 (15), each TPR element is composed of a pair of the antiparallel α-helices A and B. Proteins harboring multiple TPR elements would fold into a right-handed superhelical structure with a continuous helical groove, suitable for acting as a platform for the assembly of protein complexes (11).

Sequence comparison of the CCN1 genes from H99 and B-4551 revealed differences at seven positions. By transforming strain B-4551 with plasmids carrying ccn1 mutations, we determined that the Ts phenotype was attributable to the triplet (CAA nucleotides 859 to 861) deletion in domain A of TPR 7. The in-frame deletion of CAA resulted in the removal of lysine (residue 217), the 9th amino acid in domain A of TPR 7. The deletion of lysine contributed to the Ts phenotype as well as to the aberrant yeast morphology of B-4551 grown at 35°C. The locations of such mutations among other TPR proteins that produced thermolabile polypeptides have been studied for CDC23 and CDC27 of S. cerevisiae and nuc2+ of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (14, 15, 27). Interestingly, as with CCN1, the temperature sensitivity mutations in these genes were localized within the TPR block, particularly in the highly conserved domain A (15, 27). The mutation in each case was a single amino acid substitution of the 2nd, 6th, 8th, or 9th residue in domain A. These data highlight the functional importance of domain A among these TPR proteins. In strain B-4551, a single amino acid deletion may have modified the helical structure folding and resulted in a protein that is dysfunctional at high temperatures. The occasional cells producing short hyphal elements at 35°C suggest that the dysfunctional Ccn1p affects the budding process in some cells at a temperature higher than the optimal C. neoformans growth temperature of 30 to 32°C. C. neoformans grows strictly in yeast form in vivo unless the strain bears a mutation(s) in a gene(s) involved in budding, and no association has been observed between such hyphal forms and virulence (17).

The high homologies of Ccn1p to D. melanogaster Crnp and S. cerevisiae Clf1p led us to assume that Ccn1p is a functional homolog of Clf1p. In the complementation test, CLF1 cDNA rescued the temperature sensitivity and corrected the morphological aberrations of the ccn1 mutant. However, CCN1 failed to reciprocally rescue the clf1 null mutation. In S. cerevisiae, Clf1p was shown to be involved in pre-mRNA splicing (9) and also in cell cycle progression (25, 31). Russell and colleagues demonstrated that when CLF1 was repressed, 83% of the cells were arrested at the G2 phase (25). Work by Zhu et al. suggested that Clf1p was involved in the initiation of DNA replication. They observed that clf1 mutants exhibited delayed entry into S phase when released from the restrictive temperature of the G1 block (31). This delay was not suppressed by disruption of SIC1, the S-phase cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, suggesting that Clf1p may be involved in DNA replication (31). crn mutants of D. melanogaster die during early embryogenesis and show a variety of morphological defects including central nervous system impairment (30). In the crn mutants, DNA synthesis is reduced (30) and ultrabithorax alternative splicing is also inhibited (3).

Recently, the human crn homolog (hcrn) was identified and characterized. The hcrn protein was found to colocalize with the spliceosome assembly protein, and extracts depleted of hcrn protein failed to splice pre-mRNA (10). Taken together, the crn homologs characterized so far all appear to be involved in RNA splicing and/or cell cycle progression. We have attempted to investigate the role of CCN1 in splicing by Northern blot analysis of RNAs isolated from B-4551 and ST1-4551 yeast cells exposed to 37°C, according to the method used for S. cerevisiae (9). Several genes, such as GPD, CCN1, and RHO1, that contain multiple introns were used as probes for Northern blot analysis but failed to reveal any pre-mRNA accumulation (S. Chung, Y. C. Chang, and K. J. Kwon-Chung, unpublished data). It is possible that Ccn1p is involved in splicing but that the mRNA of B-4551 was too unstable at 37°C to detect pre-mRNA accumulation. It is also possible that Ccn1p is involved in splicing but that the mutation in the ccn1 gene of B-4551 does not affect the RNA splicing mechanism. We also performed fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis with B-4551, ST1-4551, and B-4551 complemented with CLF1. Unlike the clf1-null mutant, which showed complete arrest at the G2 phase (25) at 37°C, B-4551 showed a mere decrease in the population of cells at the G2 phase (Chung et al., unpublished) compared with those of ST1-4551 or B-4551 complemented with CLF1. The negative complementation of CCN1 in the S. cerevisiae clf1-null allele may reflect a functional discrepancy between CLF1 and CCN1. The mechanism by which CLF1 rescues the Ts phenotype of the ccn1 mutant is unclear. One possible scenario is that the TPR structure of Clf1p functions as a scaffolding factor in some other processes that might have suppressed the Ts phenotype of B-4551. It could also be that CLF1 substituted for the CCN1 function in cell cycle progression. The precise mechanism by which CLF1 complements the mutant phenotype of B-4551 remains to be elucidated.

The restoration of virulence with complementation of the Ts phenotype in B-4551 indicates that B-4551 was unable to spread into deeper tissues due to the Ts phenotype caused by the mutation in the CCN1 gene. The temperature in the subcutaneous tissue of the nasal cavity in cats may not exceed 35°C. B-4551 complemented with CCN1 caused fatal brain infection in mice within 68 days. Although the temperature of the testis is known to be around 35°C (16), no cells were recovered from the testes of mice infected with B-4551, even after 81 days. Since the intravenous route was used for inoculation, the Ts cells may have been quickly eliminated before they could be established in the testes. The present study suggests that genetic lesions in essential genes result in the Ts phenotype of C. neoformans, which thus causes superficial infection but not systemic disease. Routine culture procedures at 37°C in clinical laboratories, therefore, will be insufficient to isolate strains such as the ccn1 mutant.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. A. Bemis for the cat isolate B-4551 and Brian Rymond for the S. cerevisiae clf1 mutant and the TEF424 plasmid. We also thank Lisa Penoyer for excellent technical support and Ashok Varma for critical reading of the manuscript.

S. Chung and P. Mondon contributed equally to this work.

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Alspaugh, J. A., L. M. Cavallo, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. RAS1 regulates filamentation, mating and growth at high temperature of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 36:352-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bemis, D. A., D. J. Krahwinkel, L. A. Bowman, P. Mondon, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 2000. A temperature sensitive strain of Cryptococcus neoformans producing hyphal elements in a feline nasal granuloma. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:926-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnette, J. M., A. R. Hatton, and A. J. Lopez. 1999. Trans-acting factors required for inclusion of regulated exons in the ultrabithorax mRNAs of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 151:1517-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, Y. C., and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1994. Complementation of a capsule-deficient mutant of Cryptococcus neoformans restores its virulence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4912-4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, Y. C., and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1998. Isolation of the third capsule-associated gene, CAP60, required for virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 66:2230-2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, Y. C., and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1999. Isolation, characterization and localization of a capsule associated gene, CAP10, of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Bacteriol. 181:5636-5643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, Y. C., B. L. Wickes, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1995. Further analysis of the CAP59 locus of Cryptococcus neoformans: structure defined by forced expression and description of a new ribosomal protein gene. Gene 167:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, Y. C., L. A. Penoyer, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1996. The second capsule gene of Cryptococcus neoformans, CAP64, is essential for virulence. Infect. Immun. 64:1977-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung, S., M. R. McLean, and B. C. Rymond. 1999. Yeast ortholog of the Drosophila crooked neck protein promotes spliceosome assembly through stable U4/U6. U5 snRNP addition. RNA 5:1042-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung, S., Z. Zhou, K. A. Huddleston, D. A. Harrison, R. Reed, T. A. Coleman, and B. C. Rymond. 2002. Crooked neck is a component of the human spliceosome and implicated in the splicing process. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1576:287-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das, A. K., P. W. Cohen, and D. Barford. 1998. The structure of the tetratricopepetide repeats of protein phosphatase 5: implications for TPR-mediated protein-protein interactions. EMBO J. 5:1192-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edman, J. C., and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1990. Isolation of the URA5 gene from Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans and its use as a selection marker for transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:4538-4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goebl, M., and M. Yanagida. 1991. The TPR snap helix: a novel protein repeat motif from mitosis to transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci. 16:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heichman, K. A., and J. M. Roberts. 1996. The yeast CDC16 and CDC27 genes restrict DNA replication to once per cell cycle. Cell 85:39-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirano, T., N. Kinoshita, K. Morikawa, and M. Yanagida. 1990. Snap helix with knob and hole: essential repeats in S. pombe nuclear protein nuc2+. Cell 60:319-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon-Chung, K. J. 1979. Comparison of Sporothrix schenckii isolates obtained from fixed cutaneous lesions with isolates from other types of lesions. J. Infect. Dis. 139:424-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. E. Bennett. 1992. Medical mycology, p. 397-446. Lea & Febiger, Malvern, Pa.

- 18.Kwon-Chung, K. J., J. C. Edman, and B. L. Wickes. 1992. Genetic association of mating types and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 60:602-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon-Chung, K. J., I. Polacheck, and T. J. Popkin. 1982. Melanin-lacking mutants of Cryptococcus neoformans and their virulence for mice. J. Bacteriol. 150:1414-1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon-Chung, K. J., A. Varma, J. C. Edman, and J. E. Bennett. 1992. Selection of ura5 and ura3 mutants from the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans on 5-fluoroorotic acid medium. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 30:61-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamb, J. R., S. Tugendreich, and P. Hieter. 1995. Tetratricopeptide repeat interactions: to TPR or not to TPR? Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:257-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mondon, P., Y. C. Chang, A. Varma, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 2000. A novel episomal shuttle vector for transformation of Cryptococcus neoformans with positive selection in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187:41-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mumberg, D., R. Muller, and M. Funk. 1995. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene 156:119-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odom, A., S. Muir, E. Lim, D. L. Toffaletti, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1997. Calcineurin is required for virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 16:2576-2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell, C. S., S. Ben-Yehuda, I. Dix, M. Kupiec, and J. D. Beggs. 2000. Functional analyses of interacting factors involved in both pre-mRNA splicing and cell cycle progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 6:1565-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salas, S. D., J. E. Bennett, K. J. Kwon-Chung, J. E. Perfect, and P. R. Williamson. 1996. Effect of the laccase gene CNLAC1, on virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Exp. Med. 184:377-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sikorski, R. S., W. A. Michaud, and P. Hieter. 1993. P62cdc23 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a nuclear tetratricopeptide repeat protein with two mutable domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:1212-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varma, A., J. C. Edman, and K. J. Kwon-Chung. 1992. Molecular and genetic analysis of URA5 transformants of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 60:1101-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, K., D. Smouse, and N. Perrimon. 1991. The crooked neck gene of Drosophila contains a motif found in a family of yeast cell cycle genes. Genes Dev. 5:1080-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, W., I. R. Rainville, M. Ding, M. Bolus, N. H. Heintz, and D. S. Pederson. 2002. Evidence that the pre-mRNA splicing factor Clf1p plays a role in DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 160:1319-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]