Abstract

The molecular mechanisms used by group A Streptococcus (GAS) to survive on the host mucosal surface and cause acute pharyngitis are poorly understood. To provide new information about GAS host-pathogen interactions, we used real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) to analyze transcripts of 17 GAS genes in throat swab specimens taken from 18 pediatric patients with pharyngitis. The expression of known and putative virulence genes and regulatory genes (including genes in seven two-component regulatory systems) was studied. Several known and previously uncharacterized GAS virulence gene regulators were highly expressed compared to the constitutively expressed control gene proS. To examine in vivo gene transcription in a controlled setting, three cynomolgus macaques were infected with strain MGAS5005, an organism that is genetically representative of most serotype M1 strains recovered from pharyngitis and invasive disease episodes in North America and Western Europe. These three animals developed clinical signs and symptoms of GAS pharyngitis and seroconverted to several GAS extracellular proteins. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of throat swab material collected at intervals throughout a 12-day infection protocol indicated that expression profiles of a subset of GAS genes accurately reflected the profiles observed in the human pediatric patients. The results of our study demonstrate that analysis of in vivo GAS gene expression is feasible in throat swab specimens obtained from infected human and nonhuman primates. In addition, we conclude that the cynomolgus macaque is a useful nonhuman primate model for the study of molecular events contributing to acute pharyngitis caused by GAS.

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is the most common cause of human acute bacterial pharyngitis (2, 39). Approximately 15 million cases of streptococcal pharyngitis occur annually in the United States, representing 15 to 30% of all childhood cases of acute pharyngitis and 5 to 10% of adult cases (2). The annual direct health care costs associated with pharyngitis are approximately 2 billion dollars in the United States (7). To colonize and cause acute pharyngitis in a host, GAS must adapt to nutrient conditions existing in the upper respiratory tract and respond to innate and acquired host defense mechanisms. Many extracellular products made by GAS have been implicated in attachment, colonization, and the persistence of infection in the upper respiratory tract, including adhesins and antiphagocytic molecules such as M protein, hyaluronic acid capsule, fibronectin-binding proteins, lipoteichoic acid, streptococcal Mac protein, and streptococcal inhibitor of complement (6, 20, 27). However, many of these molecules have been studied mainly in the context of in vitro experiments or in mouse models that are unlikely to recapitulate many aspects of GAS-human molecular interactions. In addition, very little is known about the in vivo gene transcription in GAS and other microbial pathogens. Much of the available information derives from an indirect assessment of gene expression inferred from immunologic responses to cell surface components.

In vivo gene expression studies have been limited by technical problems associated with inability to obtain sufficient quantity of material from infection sites to yield interpretable results. However, we recently reported successful in vivo GAS gene transcript analysis after subcutaneous infection of mice (16), leading us to hypothesize that methods could be developed for analyzing GAS mRNA gene expression directly from human clinical material. We report here that GAS gene expression can be monitored in throat swab specimens obtained during acute pharyngitis in humans and experimentally infected nonhuman primates. Our data document the in vivo expression of (i) genes that are part of several two-component systems, (ii) other regulatory genes, and (iii) genes encoding proven and putative virulence factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and human clinical specimens.

Throat swab specimens from the posterior pharynx were collected from 18 pediatric patients presenting with signs and symptoms consistent with acute pharyngitis at a clinic in Houston, Tex. The swabs were immediately cultured to confirm GAS pharyngitis and frozen on dry ice. The GAS strains and throat swabs were shipped on dry ice by commercial courier to Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Mont. The emm type of each GAS strain was determined by methods described previously (35). The 18 strains included emm2 (n = 1 strain), emm4 (n = 2 strains), emm6 (n = 2), emm12 (n = 3), emm28 (n = 2), emm75 (n = 3), emm77 (n = 2), and emm89 (n = 3). The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine and Affiliated Hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from all human subjects.

Strain MGAS5005 (serotype M1) was used for the nonhuman primate infection studies. This organism is genetically representative of serotype M1 isolates obtained from patients with pharyngitis and invasive infections in the United States, Canada, and western Europe (22). It has been characterized extensively genetically and used in mouse models of infections and in vitro studies (16, 20, 22, 27, 29, 42, 47).

Nonhuman primates and experimental inoculation.

The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, Rocky Mountain Laboratories. Three cynomolgus macaques were used, including a juvenile female (15 months, 2.2 kg), an adult female (6 years, 8 months; 3.3 kg), and an adult male (9 years, 6 months; 7.1 kg). Two throat swabs and one venous blood specimen were collected from each animal on days 0, 2, 4, 7, 9, and 11 of the study. Day 0 samples were obtained immediately before inoculation with GAS. One swab was used to determine the level of GAS CFU by colony count measurement after overnight growth on blood agar plates, and a second swab was used to extract GAS RNA. Bacterial colonies with a morphology consistent with GAS were verified as such by sequencing of the emm gene. Plasma was separated from whole blood by centrifugation at 200 × g for 10 min.

Preinoculation throat swab specimens were collected by swabbing the tonsils vigorously with a sterile cotton applicator and culturing overnight on sheep blood agar plates. None of these specimens grew GAS. Strain MGAS5005 (serotype M1) used for experimental inoculation was cultured overnight on sheep blood agar plates at 37°C in 5% CO2, seeded into 11-ml of prewarmed Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY), and grown overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. The overnight growth was subcultured to prewarmed THY broth and incubated for 5 h to late exponential phase (i.e., an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5). The culture was centrifuged, and the bacteria were suspended in pyrogen-free sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a concentration of 107 CFU/ml. The viable bacterial cell count was verified by plating on sheep blood agar. Each monkey was anesthetized with ketamine and inoculated by dribbling 1 ml of the bacterial suspension slowly into the nares. GAS colony counts were obtained by culturing throat swabs taken on days 0, 2, 4, 7, 9, and 11. The swabs were immersed in 300 μl of sterile PBS, diluted serially in sterile PBS, plated onto sheep blood agar, and cultured overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Clinical observations of nonhuman primates inoculated with GAS.

To investigate the cynomolgus macaque as a model of acute pharyngitis, clinical observations were made by one attending veterinarian. Pharyngeal erythema, tonsil size, presence of cervical lymphadenopathy, skin condition, weight, and eating behavior were evaluated. A grading scheme was used to estimate pharyngitis severity and tonsil size. Pharyngitis was scored as follows: mild erythema with hyperemic blood vessels (+1), more intense erythema and palatal petechiae (+2), and intense erythema with palatal petechiae and exudative tonsillitis (+3). Feinstein and Levitt (9) have established criteria for scoring tonsil enlargement during human GAS pharyngitis (0 to +4). The same criteria were used except cynomolgus macaque tonsils were scored from +1 to +4 since healthy macaque tonsils resemble slightly enlarged tonsils (+1) in humans.

Extraction of GAS RNA from throat swabs.

Total RNA was extracted from throat swabs with the FastPrep FP 120 kit (Qbiogene, Carlsbad, Calif.) by immersing the swab tips directly into the FastPrep Blue tubes containing 300 μl of 5 mM ammonium aurintricarboxylate, 500 μl of CRSR-Blue (Qbiogene), and 500 μl of acid phenol-chloroform (5:1, pH 4.5; Ambion, Austin, Tex.). The mixture was homogenized (80 s at speed 5), heated at 65°C for 20 min, and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min. The aqueous phase was collected, 250 μg of glycogen (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.) was added, and the mixture was concentrated to 100 μl with a vacuum concentrator (Eppendorf). The concentrate was purified by using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen). Contaminating DNA was removed by DNase I treatment (DNA-free; Ambion). To ensure that contaminating DNA was absent, an aliquot of RNA from each sample was subjected to 40 cycles TaqMan real-time PCR for the proS gene. All swabs analyzed yielded a PCR product for the proS gene when the proS primers were tested against cDNA synthesized from the purified swab RNAs, indicating that the proS gene primer sites were conserved in all GAS strains. The RNA was treated with DNase I (Ambion) until no signal was detected by TaqMan real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) by using the conserved proS gene as a target. None of the GAS primers (Table 1) cross-hybridized to cDNAs synthesized from RNA made from the oral flora present in the monkeys (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

TaqMan real-time RT-PCR primers, probes, and their sequences

| Gene | Spy no. | Sequence (5′-3′)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward primer | Reverse primer | TaqMan probe | ||

| fasC | 244 | CACAAAAACCAATCGTGTGGATA | CAGTCAAAAAGTGGGCTGAGTTC | 6FAM-AGCCAAACGCTTTGATGCTCAGCAG-TAMRA |

| covS | 337 | CCTGGCTTGCATGGTCCT | TGGAAAACCCACGATACTGATCT | 6FAM-TCGGTCGTGTGTATCACGACCATATCG-TAMRA |

| sycF | 529 | GCGCTTTGCGTTGAATAGG | TCCTGTTCTGTGGTGTCATGGA | 6FAM-CCACAACCAAGCCCGAAATAAAACCACT-TAMRA |

| srtK | 1082 | AATCGGTTTGGCATTTGTTAAAG | GCACCTCCTCTAGCTGGATTATTC | 6FAM-TTGCTATCAAACACGGTGGGAATCTTCAAT-TAMRA |

| ciaH | 1236 | GGTCCAGGGATAACAGATGAAGAA | CCACCTGTTTGCCGTGTTC | 6FAM-AGCTTGTCAACTCGATAAAAACGATCAAAAATCTTT-TAMRA |

| zmpR | 1556 | AAAAGAAGTATCAGCAATAGCAATGG | TGCTGAGCCAAGCTTTTTAGG | 6FAM-TCAAATCAGAATCTGCCAACCGCTCA-TAMRA |

| irr | 2027 | TCGAAAATGTATTACGCGTCTCTACT | CGCTATGTTCGGTCTCATCAAC | 6FAM-CAGATGAAAAGCGCCAAATCGGAGACTTAC-TAMRA |

| perR | 187 | GCAATGATTTAACCACCTACTATGACTT | GCAATCTTCCCACATATTTCACAA | 6FAM-CCACATTGACGTGTTGATGGCCCT-TAMRA |

| crgR | 1870 | ATATGCAAGCCTATCATCTGACATC | GGATGCTGTAATGGCAACAGT | 6FAM-AGGTTGAGTTGGAATATCGGATTGAAGTGCC-TAMRA |

| mgaa | 2019 | GCGTTTGATAGCATCAAACAAGA | CATCAAGGAGATGAACCCAGTTG | 6FAM-TCACTTTTCGACAGCCCGTTGGTGA-TAMRA |

| mgab | 2019 | TGGTGATGCTGAGATTGAGCTT | GTGCTTTTGAGATTATCRATCAAGACC | 6FAM-CCRAYATCAGGAGGCAGACAAGTAACCA-TAMRA |

| mgac | 2019 | ATGAGCTGAGAAAAACGGTGACT | AGCACCTAAAAATACTAAGCTCAGTTAACT | 6FAM-CTATTACAAGGGATACTCTGCCGTCTACGACAACA-TAMRA |

| rgg | 2042 | GATAGTAAGTCAACAAAGGAAAAGAACCT | AAATAAGTCCGCTCTGTCAGACAGT | 6FAM-TTCCTCAGTAAGAGTTGCTAATAACACCTTGACCAA-TAMRA |

| mac | 861 | AGGCCTATCACACACCTACGCT | CCCGTTAGAATCAAAGTCAGCTC | 6FAM-CGTACGCATCAACCATGTTATAAACCTGTGG-TAMRA |

| grab | 1357 | TGTTGACTCACCTATCGAACAGC | TGGAGCATTGCCAAGAAGATT | 6FAM-TCGAATTATTCCAAATGGCGGAACCTTAAC-TAMRA |

| scpA | 2010 | CGAAAGAACCTTACCGCCTAGA | TTTACAATTTCGACACGCATCAA | 6FAM-GCAATTGAGCCTCAGGCATCGCA-TAMRA |

| emm | 2018 | GCTCTTGAAAAACTTAACAAAGAGCTT | TCGCTAATTGTTCTTTGAGTGCTT | 6FAM-AAAGCTGAGCTACAAGCAAAACTTGAAGCAGA-TAMRA |

| speB | 2039 | CGCACTAAACCCTTCAGCTCTT | ACAGCACTTTGGTAACCGTTGA | 6FAM-GCCTGCGCCGCCACCAGTA-TAMRA |

| sda | 2043 | CCCAAAATGTAGGAGGTCGTG | CATTCTTGAGCTCTTTGTTCGGT | 6FAM-CCAAAAAGGCGGCATGCGCT-TAMRA |

| edin | 428 | AAAACGGCGCCATGACC | GCTGCCTTGGCCCCTTT | 6FAM-ACAGATGCGCACCTCCACCGG-TAMRA |

| bspA | 843 | AGAGCCGGTATTTTCCAAGCT | TCTCAGAGTGCGTACCTGGTTTAG | 6FAM-ATGCAGCGGCAGAAGCAGAGCAGTTA-TAMRA |

| sic | 2016 | GAGGACACCCCTCCAAGTGA | TCTTGTGGATTTTTTTGAGGAGTATG | 6FAM-CCTCGTGTGCCAGAAAAACCGCA-TAMRA |

| proS | 1962 | TGAGTTTATTATGAAAGACGGCTATAGTTTC | AATAGCTTCGTAAGCTTGACGATAATC | JOE-TCGTAGGTCACATCTAAATCTTCATAGTTG-QSY-7 |

Primers and probe were designed for the mga alleles in type M1 and M12 GAS strains.

Primers and probe were designed for the mga alleles in type M2, M4, M28, M75, M77, and M89 GAS strains.

Primers and probe were designed for the mga allele in type M6 GAS strains.

TaqMan real-time PCR assay.

The sequences of the primers and probes used in the present study are listed in Table 1. The Superscript II Choice system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) was used for cDNA synthesis as described by the manufacturer. RNA purified from each swab was divided into four aliquots, to which 0.8 μg of bacteriophage MS2 carrier RNA (Roche) was added to each aliquot, and reverse transcribed with 1.5 μg of random hexamer primers at 42°C for 1 h. The cDNA samples were treated with RNase H− (Invitrogen) for 1 h and diluted with water to 100 μl. TaqMan 5′ nuclease real-time PCR assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) were carried out in a 384-well format with an 7900HT instrument (Applied Biosystems) in 10-μl reactions containing 1× universal master mix, 100 nM 6-carboxy-4′5′-dichloro-2′7′-dimethylfluorescein (JOE) and QSY-7 labeled putative prolyl-tRNA synthetase (proS, Spy1962; Table 2), 200 nM concentrations of target forward and reverse primers, and 100 nM concentrations of the target TaqMan oligonucleotide for 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min and then for 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. All TaqMan oligonucleotide probes were labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM) at the 5′ end and the quencher carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) at the 3′ end. The comparative CT method was used to determine the ratio of target and endogenous control (Applied Biosystems) as described previously (16).

TABLE 2.

Characterized or putative GAS regulatory and virulence genes analyzed in vivo

| Functional category | Spy no.a | Gene(s)a | CovRS regulationb | Putative function in GAS | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-component regulator | 242-244-245 | fasB-fasC-fasA-fas(X) | No | Growth-phase regulation | 25 |

| 336-337 | covR-covS | Yes | Negative regulator | 8, 17, 28 | |

| 529-528 | sycF-sycG | No | Unknown | 8 | |

| 1081-1082 | srtR-srtK | No | Bacteriocin regulation | 16 | |

| 1237-1236 | ciaR-ciaHc | Yes | Unknown | 52 | |

| 1556-1553 | zmpR-zmpS | Yes | Unknown | 16 | |

| 2027-2026 | irr-ihkd | Yes | Survival response to human PMNs | 8, 55 | |

| Regulator | 187 | perR | No | Unknown | 10, 47 |

| 1870 | crgR | No | Transcriptional regulator | 36 | |

| 2019 | mga | No | trans-Acting positive regulator | 4 | |

| 2042 | rgg | Yes | Transcriptional regulator | 30 | |

| Virulence factor | 861 | mac | Yes | Inhibition of phagocytosis | 27 |

| 1357 | grab | Yes | Proteinase inhibition | 41 | |

| 2010 | scpA | No | C5a peptidase | 5 | |

| 2018 | emmd | No | Adhesin and/or antiphagocytosis | 6 | |

| 2039 | speB | Yes | Extracellular cysteine protease | 34 | |

| 2043 | sda | Yes | DNase | 40 | |

| 2016 | sicd | No | Inhibition of adherence | 20 | |

| Putative virulence factor | 428 | edine | Yes | Unknown | 57 |

| 843 | bspAf | Yes | Unknown | 42 |

Spy numbers are as described by Ferretti et al. (10). Genes (and corresponding Spy numbers) measured by TaqMan real-time RT-PCR are marked in boldface.

Refers to direct or indirect regulation by CovRS (16).

Homolog of Streptococcus pneumoniae two-component regulator system ciaRH (52).

Studied only in samples from cynomolgus macaques.

Homolog of the edinC gene in Staphylococcus aureus (57).

GAS homolog of gene (bspA) identified in Bacteroides forsythus (42).

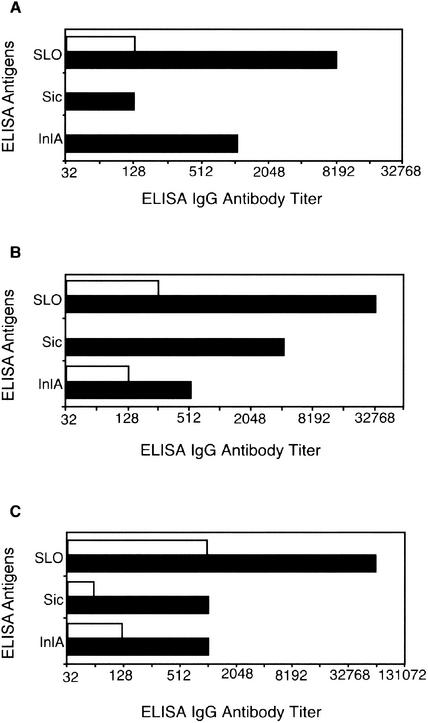

Measurement of antibody response by the nonhuman primates to GAS protein antigens.

Antibody titers to streptococcal inhibitor of complement (Sic; Spy2016), a GAS homolog of Listeria monocytogenes internalin A (InlA; Spy1361), and streptolysin O (SLO; Spy0167) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Sic and InlA were purified at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, and SLO was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Sic and InlA were diluted to 2.5 μg/ml in buffer (0.05 M Tris, pH 7.5; 0.15 M NaCl), and SLO was diluted to 10 μg/ml. Microtiter plates (Immulon-2; Dynex Technologies, Inc., Chantilly, Va.) were coated (100 μl) overnight at 4°C, washed with washing buffer (0.05 M Tris, pH 7.5; 0.15 M NaCl; 0.5% Tween 20), and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in washing buffer for 2 h at 37°C. After the washing step, 100 μl of plasma was serially diluted in washing buffer with 2% bovine serum albumin and added to the wells, and the mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Plates were washed again, and a 1:500 dilution of 100 μl of alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-monkey immunoglobulin G (Rockland, Gilbertsville, Pa.) was added to the wells, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C, and 100 μl of substrate (p-nitrophenyl phosphate; Zymed, South San Francisco, Calif.) was added. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured with an ELISA reader (Dynex Technologies, Inc.). ELISA titers are expressed as the reciprocal of plasma dilutions giving an absorbance threshold value of ≥0.3. Preinoculation plasma was used as a negative control, and the ELISA absorbance value of this sample was <0.1.

RESULTS

Expression of GAS two-component regulatory system genes in human pharyngitis.

Two-component signal transduction systems composed of a membrane-bound sensor and a cytoplasmic response regulator are important mechanisms used by pathogenic bacteria to sense and respond to environmental stimuli during interactions with the host. Pathogenic bacteria often use two-component systems to control expression of genes encoding toxins, adhesions, and other virulence-associated cell surface molecules that promote survival in vivo. The genome of a serotype M1 GAS strain that has been sequenced (10) contains genes encoding 13 two-component systems, but little is known about the function of most of these genes. Moreover, no information is available about in vivo transcription of the genes in pharyngitis episodes.

Given the importance of these genes in bacterial pathogenesis, we elected to begin our investigation by studying transcription of 6 of the 13 GAS two-component regulators (Table 2) by TaqMan real-time RT-PCR analysis of throat swab specimens obtained from 18 pediatric patients presenting with acute pharyngitis (Fig. 1). The median transcript levels of these genes were expressed as the fold difference relative to the internal normalizing gene proS. The proS gene was used as an internal reference because it is constitutively transcribed throughout the growth cycle of GAS (16). Although transcripts were detected for all six genes assayed, there was substantial variation in the relative level of transcript detected in our analysis. For example, five of the six genes (srtK, covS, zmpR, sycF, and ciaH) had a median level of relative expression that was less than the relative level of proS transcription (Fig. 1). Importantly, one gene (fasC) (25) was highly expressed, with relative transcripts being 5.8-fold higher than proS transcript levels (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Transcript levels of 17 GAS genes during human acute pharyngitis. Transcript levels of 17 GAS genes were measured from 18 pediatric throat swab RNAs with real-time RT-PCR. Gene names are listed on the left and information about each gene is presented in Table 2. GAS transcript measurements were normalized to constitutively expressed endogenous proS control gene transcript (16). The median ± two standard error transcript levels of GAS genes were expressed as a fold difference relative to the endogenous control gene proS transcript. Shown are the number of TaqMan-PCR-positive samples from the total of 18 samples analyzed.

Expression of GAS transcriptional regulators in human pharyngitis.

We next studied the level of expression of four transcriptional regulators (rgg, crgR, perR, and mga) in the throat swab specimens (Fig. 1). These genes have been characterized previously in GAS (4, 24, 30-32, 38, 44) and were selected for analysis on the basis of their potential to regulate expression of genes that may participate in host-pathogen interactions during pharyngitis. In general, expression of the positive regulator rgg was low relative to the proS gene (−13.4-fold) (Fig. 1). However, the median relative expression of rgg was 1.9-fold greater than proS in swabs recovered from one patient each infected with strains of serotype M75 and M77, a result suggesting strain-specific differences in the level of transcript of this gene. The perR gene was highly expressed (median transcript level 15.5-fold relative to proS), the recently identified cathelicidin resistance gene regulator crgR (36) had a mean transcript level of 2.5-fold relative to proS, and the median relative transcript levels of mga was 2.0-fold relative to proS (Fig. 1).

Expression of virulence genes in human GAS acute pharyngitis.

The expression level of genes encoding five proposed and two putative virulence factors was measured next (Fig. 1). Although the level of expression varied among the 18 patients, three of the genes (speB, grab, and mac) (27, 34, 41) had median relative expression levels that were less than that of proS, whereas the median relative expression level of four genes (scpA, bspA, edin, and sda) (5, 40, 42, 43, 57) exceeded the median expression level of proS. Of note, the most highly expressed gene among the 17 genes studied was sda (encoding a DNase), which had a median relative transcript level that was 61.6-fold higher than proS (Fig. 1).

Evaluation of experimental GAS pharyngitis in cynomolgus macaques.

The data presented above indicated that it was feasible to monitor transcripts of numerous GAS genes present in throat swab specimens obtained from hosts with pharyngitis. This observation, together with the lack of a small laboratory animal model that faithfully reproduces many aspects of GAS pharyngitis, led us to study gene transcript levels present in throat swabs obtained from experimentally infected nonhuman primates. An additional motivation for these studies was the capability of obtaining GAS gene transcript data during the very early phase of host-pathogen interactions in the upper respiratory tract, a goal currently not attainable in the human clinical setting.

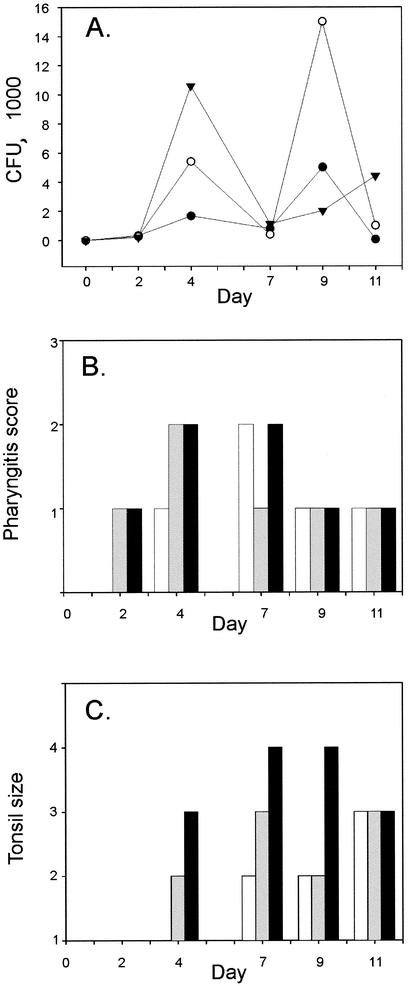

To begin this analysis, three cynomolgus macaques were inoculated with GAS strain MGAS5005 in the nares and then studied for 12 days. This strain has been studied extensively and is genetically representative of serotype M1 strains commonly causing contemporary episodes of pharyngitis and invasive disease episodes in North America and western Europe (16, 20, 22, 27, 29, 42, 47). All three monkeys were colonized with GAS 48 h after inoculation (Fig. 2A). Pharyngitis with severe erythema and palatal petechiae were observed by day 4 in the adult macaques and by day 7 in the juvenile macaque (Fig. 2B). Tonsil enlargement was evident in the adult macaques on day 4 and in the juvenile animal on day 7 (Fig. 2C). The male monkey had severe tonsil enlargement by day 7, characterized by encroachment on the midline (+4 score). Taken together, these results indicated that the animals had developed acute GAS pharyngitis with clinical findings similar to those observed in many infected humans.

FIG. 2.

Evaluation of cynomolgus macaque as model for GAS acute pharyngitis. Three cynomolgus macaques were studied on days 0, 2, 4, 7, 9, and 11 after inoculation with GAS. (A) GAS viable counting estimates were made from throat swabs collected at 6 days from a juvenile (•), an adult female (○), and an adult male (▾) macaque. (B) Pharyngitis and (C) tonsil size were scored for the juvenile (white columns), the adult female (gray columns), and the adult male (black columns) macaque after GAS inoculation on day 0. Pharyngitis was rated from 1 to 3 depending on the severity of palatal erythema. Tonsil size was scored from 1 to 4 based on the system described previously (9).

Consistent with the clinical observations, the monkeys had a significant increase in antibody titer against SLO, Sic, and the InlA homolog in serum obtained during convalescence (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Antibody response to GAS antigens in cynomolgus macaques. Antibody titers against three GAS antigens were determined by ELISA of plasma samples from juvenile (A), adult female (B), and adult male (C) macaques. Plasma titers were determined prior to GAS colonization (day 0; open bars) and 29 days after inoculation (closed columns).

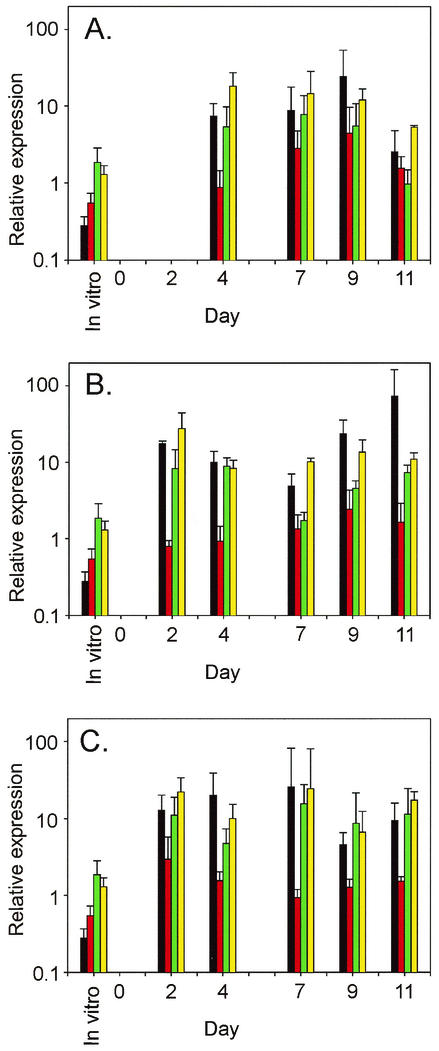

Analysis of gene expression in cynomolgus macaques.

To investigate the pattern of GAS gene expression in vivo over the course of a 12-day infection, we isolated total RNA from throat swabs obtained on days 2, 4, 7, 9, and 11 postinoculation. Relative transcript levels for the GAS genes (Table 2) were obtained by using the same techniques used for analysis of the human throat swabs. A complex pattern of transcription of the genes was detected in the three macaques (Fig. 4). For example, transcription of three genes (irr, mac, and edin) regulated directly or indirectly by the CovRS two-component system (8, 16, 17, 28), and one gene (perR) not known to be influenced by CovRS (16) was detected on days 2, 4, 7, 9, and 11 of the study in all monkeys except the day 2 sample from the juvenile animal (Fig. 4). The relative transcript levels of two gene regulators (perR and irr) varied from 1.0- to 15.6-fold and from 5.4- to 27.5-fold, respectively. Transcription of two putative virulence factors (mac and edin) also varied during the course of infection (from 2.6- to 72.8-fold and from −1.3- to 4.5-fold, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Temporal changes in GAS transcript levels during nonhuman primate model infection. Transcripts of four GAS genes were measured by real-time RT-PCR with total RNA extracted from three macaques at six time points during a 12-day acute pharyngitis study. mac (black columns), edin (red columns), perR (green columns), and irr (yellow columns) transcript levels varied during infection in juvenile (A), adult female (B), and adult male (C) macaques. Error bars indicate the standard deviation from the mean for two to four duplicate measurements.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of GAS gene expression in human clinical specimens.

To gain new insight into GAS gene expression in vivo in human patients with acute pharyngitis, we measured relative transcript levels of 17 genes in throat swab specimens by quantitative TaqMan real-time RT-PCR. Analysis of transcript levels of several genes encoding known and putative extracellular virulence factors was consistent with serological evidence that these GAS genes are expressed during infection (6, 21, 42, 43). For example, SpeB, Mac, and BspA have been shown to be synthesized in vivo in infected humans, as judged by analysis of antibody levels present in acute- and convalescent-phase sera (27, 34, 42, 43). However, our study is the first to measure transcription of GAS genes encoding two-component regulator systems and global transcriptional activators during human infection (Fig. 1). We found that the two-component regulatory system gene fasC was highly expressed during acute pharyngitis (Fig. 1). The fasBCA(X) genes have homology to agr genes of Staphylococcus aureus, a density-dependent quorum-sensing system that regulates expression of several virulence factors. Kreikemeyer et al. (25) reported that fasBCA(X) controls expression of fibronectin-binding proteins (fbp54, mrp), streptolysin S-associated genes (sagA/pel), superoxide dismutase (sod), and streptokinase (ska). The Fas regulon is upregulated under amino acid starvation (48, 49), a condition that may occur in vivo in infected hosts. Recently, Voyich et al. showed that another two-component system (irr-ihk) involved in evasion of innate immune system was also highly expressed during human pharyngitis (55).

Our studies also discovered that two regulators of gene expression (mga and perR) were highly expressed during acute pharyngitis (Fig. 1). Mga (multiple gene activator) has been studied extensively in GAS and is known to regulate several important virulence genes such as emm, scpA, mac, sic, streptococcal collagen-like protein 1 (scl1), and fibronectin-binding protein (fba), all of which have been reported to participate in adhesion to host cells or escape from host defenses (27, 29, 31, 32, 38, 51). Less is known about the role of perR in GAS gene regulation and host-pathogen interactions, although three recent studies are relevant (24, 44, 47). The GAS perR gene is homologous to the B. subtilis perR gene that is a negative regulator of response to hydrogen peroxide stress. King et al. (24) inactivated the perR gene in GAS and reported that the mutant strain was derepressed for the inducible peroxide resistance response and survived hydrogen peroxide challenge approximately 100 times better than the wild-type parental strain. More recently, Ricci et al. (44) reported that a GAS perR mutant strain was more sensitive to oxidative stress and was less virulent in a mouse air sac model than the wild-type isogenic strain. The transcript levels of perR are upregulated during growth in vitro under iron-restricted conditions (47). Hence, the identification of high levels of perR expression in vivo is consistent with the idea that this gene is highly expressed during acute pharyngitis, perhaps due to iron-restricted environmental conditions. Inasmuch as the three regulators fasBCA(X), mga, and perR were highly expressed in vivo, further studies are warranted to elucidate their contribution to human pharyngitis pathogenesis.

GAS acute pharyngitis in cynomolgus macaques.

Relevant animal models are essential to the development of a detailed understanding of the molecular interactions between pathogenic microbes and their host and to the development of new therapeutics, including vaccines. Mice can be colonized experimentally by GAS, but they do not develop an acute pharyngitis that mimics human disease (23, 29). On the basis of research conducted over decades, nonhuman primates are generally considered to be the most relevant animals for the study of experimental GAS pharyngitits (1, 12, 26, 50, 53, 56, 60). Although baboons (1) and rhesus macaques (53, 56) have been colonized successfully in the upper respiratory tract with GAS, these animals did not develop clinical signs of acute pharyngitis.

The three cynomolgus macaques inoculated with GAS developed acute pharyngitis signs similar to humans. All three monkeys were culture positive on day 2, had signs of tonsillitis and pharyngitis soon thereafter, and had an increase in serum antibody titers against the three GAS antigens tested, including SLO. The development of pharyngitis signs and increased antibody titers to extracellular secreted antigens paralled results described in earlier GAS pharyngitis studies conducted with chimpanzees, a species used previously to study GAS acute pharyngitis (12, 26, 60). In the aggregate, our results indicate that the cynomolgus macaque is a useful animal for experimental study of acute pharyngitis caused by GAS.

Use of monkeys to study the molecular processes contributing to GAS pharyngitis permits several types of analyses to be conducted that are not readily performed with human subjects. For example, GAS infection can be studied at precisely delineated times after inoculation, whereas human studies involve undefined time periods between exposure to the organism and presentation with clinical symptoms. Second, the monkey model permits analysis of infection pathogenesis with defined strains, including particular M protein serotypes of special interest in pharyngitis, and isogenic mutant strains. Third, inoculated monkeys are housed under controlled conditions; hence, they are subject to far less environmental variation than human patients. Despite reduction in the spectrum of confounding variables, significant variation was observed in GAS gene expression and the host clinical response between monkeys over the course of the infection. Variation in host response to GAS inoculation has been reported previously in a baboon model of GAS upper respiratory tract infection and was attributed to inconsistent development of opsonic antibodies and ineffectiveness in clearance of GAS (1). Expression differences in GAS transcript levels were also observed in cynomolgus macaques and humans (Fig. 1 and 4). The reasons for these differences are largely unknown; however, they may in part be due to variation in infecting GAS strains or the time of sampling.

Analysis of bacterial gene transcripts in vivo.

Analysis of quantitative bacterial gene transcript levels directly from clinical samples has been reported for relatively few pathogens (Table 3). Most studies have used real-time RT-PCR to measure transcript levels. Due to the detection limit with the real-time RT-PCR method (103 to 104 transcripts/sample) (14, 45), it has been not been possible to quantitate transcript levels of more than ∼20 genes by this method. Although the 384-well multiplexing format we used permitted us to achieve high throughput and quantitative RT-PCR results, expression microarray analysis of the complete bacterial transcriptome is clearly the preferred strategy for future experiments due to the comprehensive data set obtained. In this regard, we note that Merrell et al. (33) recently reported successful analysis of the Vibrio cholerae transcriptome by using 1 μg of RNA extracted from human stool. Studies of the complete in vivo transcriptome undoubtedly will provide many new insights into GAS host-pathogen interactions.

TABLE 3.

Publications describing direct quantitation of bacterial transcripts in vivo

| Species | Sample source | No. of genes | Method | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Tick | 7 | Light Cycler real-time RT-PCR | 13 |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Mouse and tick | 5 | TaqMan real-time RT-PCR | 19 |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Mouse and tick | 3 | Competitive RT-PCR | 11 |

| Helicobacter pylori | Human and mouse model | 4 | Light Cycler real-time RT-PCR | 45 |

| Helicobacter pylori | Mouse | 3 | Competitive RT-PCR | 3 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | Human | 7 | TaqMan real-time RT-PCR | 46 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Human and guinea pig | 2 | Light Cycler real-time RT-PCR | 14, 15, 59 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Rat | 2 | TaqMan real-time RT-PCR | 54 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Rabbit | 68 | cDNA microarray | 58 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Mouse | 17 | TaqMan real-time RT-PCR | 16 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Human | 1 | TaqMan real-time RT-PCR | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Mouse | 5 | Comparative RT-PCR | 37 |

| Vibrio cholerae | Human | 3,357 | cDNA microarray | 33 |

Acknowledgments

We thank G. J. Adams and T. Downey for assistance with statistical analysis; B. Lei and S. D. Reid for providing recombinant purified GAS proteins; M. Gutacker for translating foreign journal articles; M. Liu and D. E. Sturdevant for technical assistance; and W. Sheets, R. Larson, and D. Dale for assistance with the animal experiments. We are especially indebted to the physicians, support staff, and the patients at the Pediatric Medical Group (an affiliate of Texas Children's Pediatric Associates), Houston, Tex.

This work was supported in part by contract N01-AO-02738 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashbaugh, C. D., T. J. Moser, M. H. Shearer, G. L. White, R. C. Kennedy, and M. R. Wessel. 2000. Bacterial determinants of persistent throat colonization and the associated immune response in a primate model of human group A streptococcal pharyngeal infection. Cell. Microbiol. 2:283-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisno, A. L. 2001. Acute pharyngitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blom, K., A.-M. Svennerholm, and I. Bolin. 2002. The expression of the Helicobacter pylori genes ureA and nap is higher in vivo than in vitro as measured by quantitative competitive reverse transcriptase-PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Med. Microbiol. 32:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caparon, M. G., and J. R. Scott. 1987. Identification of a gene that regulates expression of M protein, the major virulence determinant of group A streptococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8677-8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, C. C., and P. P. Cleary. 1990. Complete nucleotide sequence of the streptococcal C5a peptidase gene of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Biol. Chem. 265:3161-3167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale, J. B. 1999. Group A streptococcal vaccines. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 13:227-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federle, M. J., K. S. McIver, and J. R. Scott. 1999. A response regulator that represses transcription of several virulence operons in the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 181:3649-3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinstein, A. R., and M. Levitt. 1970. The role of tonsils in predisposing to streptococcal infections and recurrences of rheumatic fever. N. Engl. J. Med. 282:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fikrig, E., W. Feng, S. W. Barthold, S. R. Telford III, and R. A. Flavell. 2000. Arthropod- and host-specific Borrelia burgdorferi bbk32 expression and the inhibition of spriochete transmission. J. Immunol. 164:5344-5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friou, G. J. 1950. Experimental infection of the upper respiratory tract of young chimpanzees with group A hemolytic streptococci. J. Infect. Dis. 86:264-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmore, R. D., Jr., M. L. Mbow, and B. Stevenson. 2001. Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression during life cycle phases of the tick vector Ixodes scapularis. Microbes Infect. 3:799-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goerke, C., M. G. Bayer, and C. Wolz. 2001. Quantification of bacterial transcripts during infection using competitive reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and LightCycler RT-PCR. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:279-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goerke, C., U. Fluckiger, A. Steinhuber, W. Zimmerli, and C. Wolz. 2001. Impact of the regulatory loci agr, sarA and sae of Staphylococcus aureus on the induction of α-toxin during device-related infection resolved by direct quantitative transcript analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1439-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham, M. R., L. M. Smoot, C. A. Migliaccio, K. Virtaneva, D. E. Sturdevant, S. F. Porcella, M. J. Federle, G. J. Adams, J. R. Scott, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Virulence control in group A Streptococcus by a two-component gene regulatory system: global expression profiling and in vivo infection modeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13855-13860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath, A., V. J. DiRita, N. L. Barg, and N. C. Engleberg. 1999. A two-component regulatory system, CsrR-CsrS, represses expression of three Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors, hyaluronic acid capsule, streptolysin S, and pyrogenic exotoxin B. Infect. Immun. 67:5298-5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodzic, E., D. L. Borjesson, S. Feng, and S. W. Barthold. 2001. Acquisition dynamics of Borrelia burgdorferi and the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis at the host-vector interface. Vector-Borne Zoonot. Dis. 1:149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodzic, E., S. Feng, K. J. Freet, D. L. Borjesson, and S. W. Barthold. 2002. Borrelia burgdorferi population kinetics and selected gene expression at the host-vector interface. Infect. Immun. 70:3382-3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoe, N. P., R. M. Ireland, F. R. DeLeo, B. B. Gowen, D. W. Dorward, J. M. Voyich, M. Liu, E. H. Burns, Jr., D. M. Culnan, A. Bretscher, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Insight into the molecular basis of pathogen abundance: group A Streptococcus inhibitor of complement inhibits bacterial adherence and internalization into human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7646-7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoe, N. P., P. Kordari, R. Cole, M. Liu, T. Palzkill, W. Huang, D. McLellan, G. J. Adams, M. Hu, J. Vuopio-Varkila, T. R. Cate, M. E. Pichichero, K. M. Edwards, J. Eskola, D. E. Low, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Human immune response to streptococcal inhibitor of complement, a serotype M1 group A Streptococcus extracellular protein involved in epidemics. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1425-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoe, N. P., K. Nakashima, S. Lukomski, D. Grigsby, M. Liu, P. Kordari, S. J. Dou, X. Pan, J. Vuopio-Varkila, S. Salmelinna, A. McGeer, D. E. Low, B. Schwartz, A. Schuchat, S. Naidich, D. De Lorenzo, Y. X. Fu, and J. M. Musser. 1999. Rapid selection of complement-inhibiting protein variants in group A Streptococcus epidemic waves. Nat. Med. 5:924-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Husmann, L. K., D. L. Dillehay, V. M. Jennings, and J. R. Scott. 1996. Streptococcus pyogenes infection in mice. Microb. Pathog. 20:213-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King, K. Y., J. A. Horenstein, and M. G. Caparon. 2000. Aerotolerance and peroxide resistance and PerR mutants of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 182:5290-5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreikemeyer, B., M. D. Boyle, B. A. Buttaro, M. Heinemann, and A. Podbielski. 2001. Group A streptococcal growth phase-associated virulence factor regulation by a novel operon (Fas) with homologies to two-component-type regulators requires a small RNA molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 39:392-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krushak, D. H., R. A. Zimmerman, and B. L. Murphy. 1970. Induced group A beta-hemolytic streptococcic infection in chimpanzees. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 157:742-744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei, B., F. R. DeLeo, N. P. Hoe, M. R. Graham, S. M. Mackie, R. L. Cole, M. Liu, H. R. Hill, D. E. Low, M. J. Federle, J. R. Scott, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evasion of human innate and acquired immunity by a bacterial homolog of CD11b that inhibits opsonophagocytosis. Nat. Med. 7:1298-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin, J. C., and M. R. Wessels. 1998. Identification of csrR/csrS, a genetic locus that regulates hyaluronic acid capsule synthesis in group A Streptococcus. Mol. Microbiol. 30:209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukomski, S., K. Nakashima, I. Abdi, V. J. Cipriano, R. M. Ireland, S. D. Reid, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and characterization of the scl gene encoding a group A Streptococcus extracellular protein virulence factor with similarity to human collagen. Infect. Immun. 68:6542-6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyon, W. R., C. M. Gibson, and M. G. Caparon. 1998. A role for trigger factor and an rgg-like regulator in the transcription, secretion and processing of the cysteine proteinase of Streptococcus pyogenes. EMBO J. 17:6263-6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIver, K. S., and J. R. Scott. 1997. Role of mga in growth phase regulation of virulence genes of the group A Streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 179:5178-5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIver, K. S., A. S. Thurman, and J. R. Scott. 1999. Regulation of mga transcription in the group A Streptococcus: specific binding of Mga within its own promoter and evidence for a negative regulator. J. Bacteriol. 181:5373-5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merrell, D. S., S. M. Butler, F. Qadri, N. A. Dolganov, A. Alam, M. B. Cohen, S. B. Calderwood, G. K. Schoolnik, and A. Camilli. 2002. Host-induced epidemic spread of the cholera bacterium. Nature 417:642-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musser, J. M. 1997. Streptococcal superantigen, mitogenic factor, and pyrogenic exotoxin B expressed by Streptococcus pyogenes: structure and function. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 27:143-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musser, J. M., V. Kapur, J. Szeto, X. Pan, D. S. Swanson, and D. R. Martin. 1995. Genetic diversity and relationships among Streptococcus pyogenes strains expressing serotype M1 protein: recent intercontinental spread of a subclone causing episodes of invasive disease. Infect. Immun. 63:994-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nizet, V., T. Ohtake, X. Lauth, J. Trowbridge, J. Rudisill, R. A. Dorschner, V. Pestonjamasp, J. Piraino, K. Huttner, and R. L. Gallo. 2001. Innate antimicrobial peptide protects the skin from invasive bacterial infection. Nature 414:454-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogunniyi, A. D., P. Giammarinaro, and J. C. Paton. 2002. The genes encoding virulence-associated proteins and the capsule of Streptococcus pneumoniae are upregulated and differentially expressed in vivo. Microbiology 148:2045-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez-Casal, J. F., H. F. Dillon, L. K. Husmann, B. Graham, and J. R. Scott. 1993. Virulence of two Streptococcus pyogenes strains (types M1 and M3) associated with toxic-shock-like syndrome depends on an intact mry-like gene. Infect. Immun. 61:5426-5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pichichero, M. E. 1998. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections. Pediatr. Rev. 19:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Podbielski, A., I. Zarges, A. Flosdorff, and J. Weber-Heynemann. 1996. Molecular characterization of a major serotype M49 group A streptococcal DNase gene (sdaD). Infect. Immun. 64:5349-5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasmussen, M., H. P. Müller, and L. Björck. 1999. Protein GRAB of Streptococcus pyogenes regulates proteolysis at the bacterial surface by binding α2-macroglobulin. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15336-15344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reid, S. D., N. M. Green, J. K. Buss, B. Lei, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Multilocus analysis of extracellular putative virulence proteins made by group A Streptococcus: population genetics, human serologic response, and gene transcription Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7552-7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reid, S. D., N. M. Green, G. L. Sylva, J. M. Voyich, E. T. Stenseth, F. R. DeLeo, T. Palzkill, D. E. Low, H. R. Hill, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Postgenomic analysis of four novel antigens of group A Streptococcus: growth-phase-dependent gene transcription and human serologic response. J. Bacteriol. 184:6316-6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ricci, S., R. Janulczyk, and L. Bjorck. 2002. The regulator PerR is involved in oxidative stress response and iron homeostasis and is necessary for full virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:4968-4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rokbi, B., D. Seguin, B. Guy, V. Mazarin, E. Vidor, F. Mion, M. Cadoz, and M.-J. Quentin-Millet. 2001. Assessment of Helicobacter pylori gene expression within mouse and human gastric mucosae by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR. Infect. Immun. 69:4759-4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shelburne, C. E., R. M. Gleason, G. R. Germaine, L. F. Wolff, B. H. Mullally, W. A. Coulter, and D. E. Lopatin. 2002. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of Porphyromonas gingivalis gene expression in vivo. J. Microbiol. Methods 49:147-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smoot, L. M., J. C. Smoot, M. R. Graham, G. A. Somerville, D. E. Sturdevant, C. A. Migliaccio, G. L. Sylva, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Global differential gene expression in response to growth temperature alteration in group A Streptococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10416-10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steiner, K., and H. Malke. 2000. Life in protein-rich environments: the relA-independent response of Streptococcus pyogenes to amino acid starvation. Mol. Microbiol. 38:1004-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steiner, K., and H. Malke. 2001. relA-independent amino acid starvation response network of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 183:7354-7364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taranta, A., M. Spagnuolo, M. Davidson, G. Goldstein, and J. W. Uhr. 1969. Experimental streptococcal infections in baboons. Transplant. Proc. 1:992-993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terao, Y., S. Kawabata, E. Kunitomo, J. Murakami, I. Nakagawa, and S. Hamada. 2001. Fba, a novel fibronectin-binding protein from Streptococcus pyogenes, promotes bacterial entry into epithelial cells, and the fba gene is positively transcribed under the Mga regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 42:75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Throup, J. P., K. K. Koretke, A. P. Bryant, K. A. Ingraham, A. F. Chalker, Y. Ge, A. Marra, N. G. Wallis, J. R. Brown, D. J. Holmes, M. Rosenberg, and M. K. Burnham. 2000. A genomic analysis of two-component signal transduction in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 35:566-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanace, P. W. 1960. Experimental streptococcal infection in the rhesus monkey. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 85:910-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandecasteele, S. J., W. E. Peetermans, R. Merckx, M. van Ranst, and J. van Eldere. 2002. Use of gDNA as internal standard for gene expression in staphylococci in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 291:528-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voyich, J. M., D. E. Sturdevant, K. R. Braughton, S. D. Kobayashi, B. Lei, K. Virtaneva, D. W. Dorward, J. M. Musser, and F. R. DeLeo. 2003. Bacterial pathogen genome-wide protective response to human innate immunity: molecular strategies used by group A Streptococcus to evade destruction by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1996-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Watson, R. F., S. Rothbard, and H. F. Swift. 1946. Type-specific protection and immunity following intranasal inoculation of monkeys with group A hemolytic streptococci. J. Exp. Med. 84:127-142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamaguchi, T., T. Hayashi, H. Takami, M. Ohnishi, T. Murata, K. Nakayama, K. Asakawa, M. Ohara, H. Komatsuzawa, and M. Sugai. 2001. Complete nucleotide sequence of a Staphylococcus aureus exfoliative toxin B plasmid and identification of a novel ADP-ribosyltransferase, EDIN-C. Infect. Immun. 69:7760-7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yarwood, J. M., J. K. McCormick, M. L. Paustian, V. Kapur, and P. M. Schlievert. 2002. Repression of the Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator in serum and in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 184:1095-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiong, Y.-Q., W. van Wamel, C. C. Nast, M. R. Yeaman, A. L. Cheung, and A. S. Bayer. 2002. Activation and transcriptional interaction between agr RNAII and RNAIII in Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in an experimental endocarditis model. J. Infect. Dis. 186:668-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zimmerman, R. A., D. H. Krushak, E. Wilson, and J. D. Douglas. 1970. Human streptococcal disease syndrome compared with observations in chimpanzees. II. Immunologic responses to induced pharyngitis and the effect of treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 122:280-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]