Abstract

Ovine neutrophils spontaneously underwent apoptosis during culture in vitro, as assessed by morphological changes and exposure of annexin V binding sites on their cell surfaces. The addition of conditioned medium from concanavalin A-treated ovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) could partially protect against this progression into apoptosis, but dexamethasone and sodium butyrate could not. Actinomycin D accelerated the rate at which ovine neutrophils underwent apoptosis. Neutrophils isolated from sheep experimentally infected with Anaplasma phagocytophilum showed significantly delayed apoptosis during culture ex vivo, and the addition of conditioned medium from PBMC to these cells could not delay apoptosis above the protective effects observed after in vivo infection. The ability of neutrophils from A. phagocytophilum-infected sheep to activate a respiratory burst was increased compared to the activity measured in neutrophils from uninfected sheep, but chemotaxis was decreased in neutrophils from infected sheep. These data are the first demonstration that in vivo infection with A. phagocytophilum results in changes in rates of apoptosis of infected immune cells. This may help explain how these bacteria replicate in these normally short-lived cells.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly known as Ehrlichia phagocytophila and Cytoecetes phagocytophila) is the causative agent of tick-borne fever in sheep and pasture fever in cattle. It is an obligately intracellular bacterium whose main mammalian targets are granulocytes, although it can also infect monocytes (32). The disease is common in the United Kingdom and other parts of Western Europe such as Scandinavia, where its vector is the temperate tick, Ixodes ricinus (20, 29, 33). The first case of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) was described in the United States in 1994 (7), and it has since been described in Europe. The agent of HGE is morphologically identical to E. phagocytophila and E. equi (3, 7, 19), and it has been proposed that these are variants of the same species, since they have only minor variations in their 16S rRNA genes and 100% identity in their GroESL amino acid sequences (11). It has thus been proposed that these three granulocytic members of the genus Ehrlichia be united within one species and transferred to the genus A. phagocytophilum (11) since their gene sequences were closer to those of A. marginale and E. platys than to other ehrlichiae.

Neutrophils form the first line of defense against invading bacteria and fungi, and possess a powerful array of cytotoxic enzymes, reactive oxidants, and associated processes. These include the ability to generate reactive oxidant species via the combined activities of the NADPH oxidase and myeloperoxidase (12, 13) and a range of granule proteins that include proteases, defensins, and other permeability-inducing factors (14). Neutrophils have high rates of spontaneous apoptosis and a corresponding very short half-life in the circulation of only 6 to 12 h (2, 26). However, this half-life can be considerably extended in vitro (during cytokine treatment) and in vivo during inflammation (6, 8, 22, 24). In view of this high cytotoxic potential and short half-life, the neutrophil would seem to be an unlikely and unsuitable target for intracellular pathogens such as A. phagocytophilum. To become a more suitable host, the bacterium would have to evade the antimicrobial systems of neutrophils that are normally activated upon phagocytosis and, ideally, should extend the neutrophil life span by delaying apoptosis.

It has been shown that HGE infection of the promyelocytic cell line HL-60 results in a downregulation of NADPH oxidase activity that is attributable to a decrease in cellular levels of mRNA that encodes the cytochrome b (gp91-phox) of the NADPH oxidase (4). This bacterium is also associated with a downregulation of superoxide production by human neutrophils via a process that required HGE-neutrophil contact and protein synthesis by the neutrophils (23). This inhibitory response is neutrophil specific since inhibition of superoxide production by monocytes was not affected by HGE. HGE infection induces apoptosis in cultured HL-60 cells (21) but delays apoptosis in human neutrophils (37). Thus, the organism appears to have the ability to downregulate a major neutrophil cytotoxic mechanism and delay apoptosis, thereby facilitating its survival in the host and ability to spread through the body.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether in vivo infection of sheep neutrophils with an ovine strain, A. phagocytophilum, affects ovine neutrophil function ex vivo and, in particular, whether it affected the kinetics of apoptosis and respiratory burst activation. We measured functions of ovine neutrophils before and after experimental infection with A. phagocytophilum. We have been able to demonstrate that neutrophils isolated from sheep at the height of infection (i.e., the second day of bacteremia) have significantly delayed spontaneous apoptosis compared to samples obtained before infection. Furthermore, exogenous agents that protect against apoptosis in control cells did not exert any protective effects above those afforded by in vivo infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Percoll was purchased from Pharmacia (St. Albans, United Kingdom), HEPES-supplemented RPMI 1640 medium was from ICN Biochemicals (Thame, Oxford, United Kingdom), while fetal calf serum (FCS) and l-glutamine were from Gibco-BRL (Paisley, United Kingdom). Nitrocellulose membranes were from Millipore (Bedford, Mass) and casein was purchased from Calbiochem (Nottingham, United Kingdom). Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), zymosan, concanavalin A, cycloheximide, actinomycin D, and casein were from Sigma (Poole, United Kingdom). All other reagents were of the highest purity available.

A. phagocytophilum.

Heparinized ovine blood stabilites of the Old Sourhope strain were stored at −114°C with 10% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide as a cryopreservative (32-34).

Infection of sheep with A. phagocytophilum.

Eight 1-year-old Cambridge sheep, bred and maintained in a tick-free environment, were inoculated intravenously with 1 ml of a 10% dilution of the stabilite in phosphate-buffered saline (10 mM potassium phosphate, 0.9% NaCl; pH 7.4). The sheep were then monitored for clinical and hematological changes for up to 10 days. Rectal temperatures and blood samples into EDTA-coated tubes were taken daily. The blood samples were used to measure total and differential white blood counts and were analyzed for the presence of cytoplasmic inclusions of A. phagocytophilum in granulocytes and monocytes, as described previously (32). Larger volumes (60 to 100 ml) of blood were collected on three occasions: just prior to infection, on the second day of bacteremia (peak infection), and on the fourth day of bacteremia (late infection) (32-34). These samples were used to prepare neutrophils for functional assays, as described below.

Neutrophil isolation and purification.

Purified populations of ovine neutrophils were obtained from healthy sheep and from sheep infected with A. phagocytophilum, as described previously (35). Blood samples collected into EDTA-coated vacutainers were centrifuged at 400 × g for 30 min and then the plasma and buffy coats (containing mostly mononuclear cells) were removed. Sterile distilled water was added to the packed cell pellets containing red cells and granulocytes (36 ml of water per 10-ml packed cell pellet) to lyse the red cells with gentle agitation for 20 s. Isotonicity was restored by the addition of 9% NaCl (4 ml), and the white blood cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min and washed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.2 mg of EDTA/liter. The cells were then centrifuged at 500 × g for 30 min on a cushion of 65% Percoll (density, 1.093 g/ml). Because the ovine neutrophils infected with A. phagocytophilum have a lower buoyant density than uninfected neutrophils, a 55% Percoll cushion (1.078 g/ml) was used when blood samples were obtained from sheep during the second and fourth days of bacteremia (35). After centrifugation, the supernatants were discarded and the neutrophil pellets were washed and finally suspended in RPMI 1640 medium. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion, whereas purity was determined by cytocentrifugation and differential staining. These were routinely >98% and >95%, respectively, for normal and infected cells immediately after isolation (35).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation and culture.

The buffy coat layer, which is predominantly composed of mononuclear cells, was used as sources of PBMCs. Contaminating red blood cells were lysed by osmotic shock (as described above), followed by the addition of 9% NaCl to restore isotonicity. The washed cells were suspended at 2 × 107/ml in HEPES-containing RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FCS and 2 mM l-glutamine. The cells were then incubated in the absence (control) or presence of concanavalin A (25 μg/ml) for 22 h at 37°C. After culture, supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until required.

Neutrophil culture.

Neutrophils were cultured for 22 h with gentle agitation at 37°C at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml in HEPES-containing RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FCS and 2 mM l-glutamine. Neutrophil suspensions were supplemented with PBMC-conditioned medium, cycloheximide (10 μg/ml), actinomycin D (1 μM), sodium butyrate (0.4 mM), and dexamethasone (1 μM). These agents have been shown to accelerate or delay apoptosis in human neutrophils (6, 8, 24, 35).

Measurement of apoptosis.

Purified neutrophils (2.5. × 106 cells/ml) were suspended in HEPES-containing RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FCS and 2 mM l-glutamine. As indicated, cultures were also supplemented with PBMC-conditioned medium, cycloheximide (10 μg/ml), actinomycin D (1 μM), and sodium butyrate (0.4 mM), all of which have been previously shown to affect apoptosis of human neutrophils (6, 8, 24, 27). Recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and gamma interferon were without effect on apoptosis of ovine neutrophils (data not shown). Morphological assessment of apoptosis was performed as previously described (24). Briefly, 105 cells were cytocentrifuged (Shandon Cytospin 3; Runcorn, Cheshire, United Kingdom) and May-Grünwald-Giemsa stained, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined from at least 500 cells. This method has been shown to correlate well with other markers of apoptosis (26). Apoptosis was also measured by the appearance of phosphatidylserine on the surface of cells. Neutrophils (106) were removed from culture and resuspended in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) without phenol red (Gibco-BRL), before the addition of annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Sigma) at a 1:100 dilution. After 10 min on ice, cells were pelleted at 400 × g and resuspended in HBSS without phenol red before analysis by flow cytometry with a Cytoron Absolute bench top flow cytometer system (Ortho Diagnostics) by using a protocol that samples a precisely known volume. This protocol also provides information on the cell density of the original culture. From these data, the percentage of apoptotic (annexin V-positive) and nonapoptotic (annexin V-negative) neutrophils can be determined.

NADPH oxidase activity.

Chemiluminescence was measured at 37°C in neutrophil suspensions (5 × 105/ml) in HBSS medium that was supplemented with 10 μM luminol by using a Dynatech ML-1000 luminometer (10, 15, 16). Cells were stimulated by the addition of PMA (0.1 μg/ml) or yeast zymosan (100 μg/ml) previously opsonized with ovine serum.

Statistics.

Data were analyzed by using a paired Student t test. The data shown are means ± the standard deviation (SD).

RESULTS

Infection rates of ovine neutrophils.

The neutrophils analyzed in these studies were taken from sheep before and during the second and fourth days of bacteremia. A. phagocytophilum was detected by microscopy of stained neutrophil films. On the second day of bacteremia 67.4% ± 14.1% (range, 44 to 89% [data from eight animals]) of the neutrophils were shown to contain bacteria, whereas on the fourth day of bacteremia 38.3% ± 14.8% (range, 18 to 61% [data from eight animals]) of the neutrophils were infected. These results are in broad agreement with those published previously (32).

Effects of exogenous agents on sheep neutrophil apoptosis.

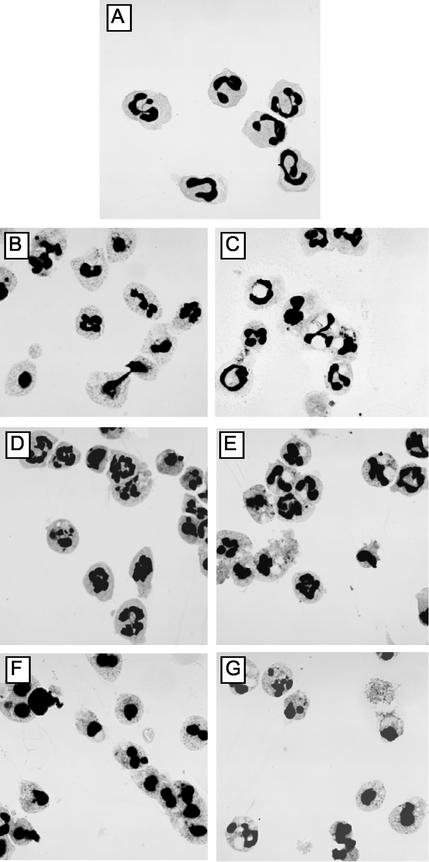

Freshly isolated neutrophils were >99% nonapoptotic, as indicated by morphology and annexin V binding. Thus, nonapoptotic cells had a distinguishable multilobed nucleus, granular cytoplasm, and negligible binding of annexin V (Fig. 1 and 2). However, after 22 h of incubation in culture in vitro, neutrophil apoptosis increased such that ca. 45% ± 5% and 75% ± 2% were apoptotic, respectively, as assessed by increased annexin V binding and morphology (Fig. 1 to 3). We then tested a number of agents that have been shown to affect rates of apoptosis in human neutrophils.

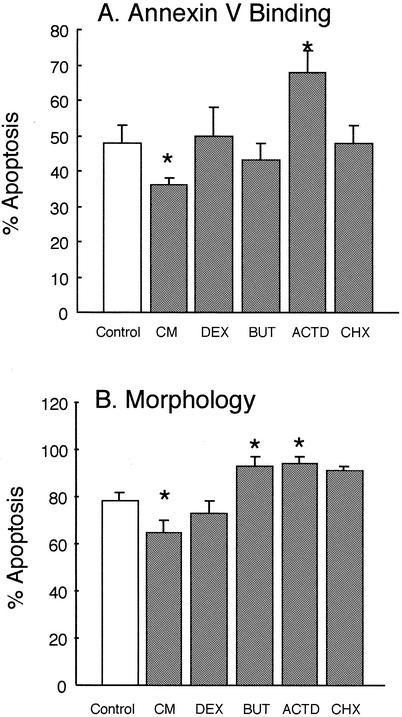

FIG. 1.

Effects of exogenous agents on apoptosis of ovine neutrophils. Purified ovine neutrophils were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM l-glutamine at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml. They were then incubated for 22 h at 37°C as follows: Control, no additions; CM, conditioned medium obtained from concanavalin A-stimulated PBMCs, as described in Materials and Methods; DEX, dexamethasone at 1 μM; BUT, sodium butyrate at 0.4 mM; ACTD, actinomycin D at 1 μM; CHX, cycloheximide at 10 μg/ml. After culture, apoptosis was assessed by binding to FITC-annexin V and flow cytometry (A) and by morphological examination of cytospins (B). Immediately after isolation, neutrophils were 100% nonapoptotic, as assessed by these criteria. Values shown are means ± the SD (n = 6). Values indicated by asterisks are significantly different from the control values (P < 0.05).

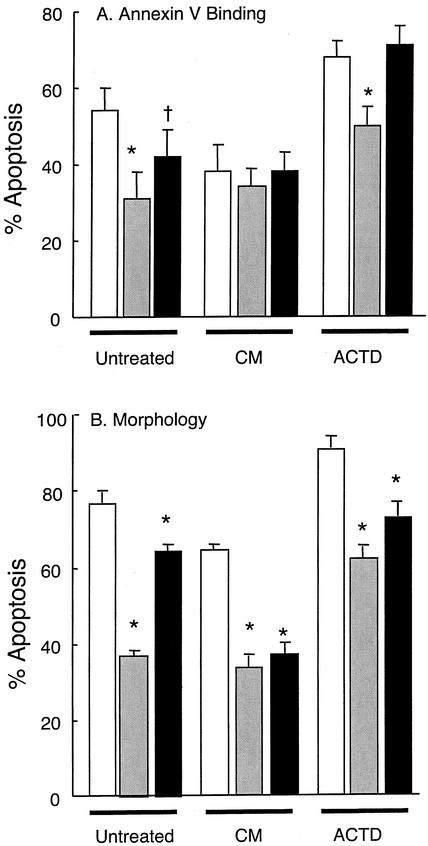

FIG. 2.

Effects of A. phagocytophilum infection on neutrophil apoptosis. Neutrophils were isolated from the venous blood of sheep prior to infection (□) and on the second (░⃞) and fourth (▪) days of bacteremia. Purified neutrophils were then incubated in RPMI 1640 medium as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Cultures contained no further additions (Untreated), PBMC conditioned medium (CM), or actinomycin D (ACTD). After culture with gentle agitation at 37°C for 22 h, apoptosis was determined by FITC-annexin V binding (A) and morphology (B). Values shown are means ± the SD (n = 6). Values statistically different to the preinfection values are indicated by an asterisk (P = 0.01) or a dagger (P = 0.05).

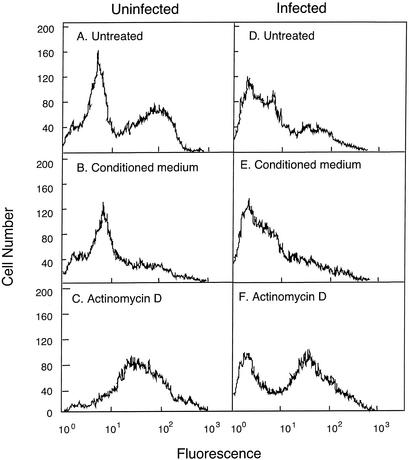

FIG. 3.

Changes in annexin V binding to ovine neutrophils. Neutrophils were isolated from ovine blood prior to infection (Uninfected) and on the second day of bacteremia (Infected) after experimental infection of the sheep with A. phagocytophilum. The purified neutrophils were then incubated in the absence (Untreated, A and D) or the presence of PBMC conditioned medium (B and E) or Actinomycin D (C and D) for 22 h at 37°C with gentle agitation, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. They were then labeled with FITC-annexin V and examined by flow cytometry. The data shown are from an individual sheep before and after infection. Similar results were obtained for five other sheep.

However, conditioned medium obtained from concanavalin A-treated ovine PBMC resulted in a small, but significant (P < 0.01) delay in apoptosis of ovine neutrophils after 22 h of incubation (Fig. 1 to 3). Dexamethasone, which has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of apoptosis in human neutrophils (9), resulted in a slight delay in apoptosis as assessed by morphology but not when annexin V binding was measured. Similarly, sodium butyrate, which also delays apoptosis in human neutrophils (24, 27) did not significantly affect apoptosis of ovine neutrophils. Actinomycin D (an inhibitor of transcription) but not cycloheximide (an inhibitor of translation) accelerated apoptosis, as has been reported previously for human neutrophils (24, 27, 31).

Effects of in vivo A. phagocytophilum infection on rates of neutrophil apoptosis.

The proportion of apoptotic cells in freshly isolated populations of ovine neutrophils obtained during the peak of bacteremia was not significantly different to that obtained prior to infection. There was no significant effect of A. phagocytophilum infection on neutrophil apoptosis of freshly isolated cells compared to those obtained from control, uninfected animals. Thus, in control and infected animals, <2% of freshly isolated neutrophils were apoptotic (Fig. 4). However, after 22 h culture in vitro, rates of apoptosis in A. phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils were significantly (P < 0.01) lower than those obtained from control, uninfected animals. Thus, for control animals, rates of neutrophil apoptosis by 22 h of incubation were 52% ± 5% and 78% ± 2% for annexin V binding and morphology, respectively, while comparable values of neutrophils isolated from sheep at the peak of bacteremia were 30% ± 7% and 35% ± 2%, respectively. Treatment of neutrophils for 22 h with conditioned medium from concanavalin A-treated PBMCs, significantly delayed the apoptosis of neutrophils from uninfected sheep, but this protective effect was not as great in A. phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils. Thus, the cytokines present in PBMC conditioned medium cannot delay ovine neutrophil apoptosis much above the protection seen during in vivo infection with A. phagocytophilum. In neutrophils isolated from sheep at the fourth day of bacteraemia, neutrophil apoptosis after 22 h of incubation in culture was higher than that seen in neutrophils isolated at the peak of infection (second day of bacteremia) but still significantly lower than that seen in control, uninfected neutrophils incubated for the same time. These cells had partially regained their sensitivity to PBMC conditioned medium, since a significantly protective effect on apoptosis was observed.

FIG. 4.

Changes in neutrophil morphology during culture. Cytospins were prepared from purified neutrophil suspensions from uninfected (A, B, D, and F) and from A. phagocytophilum-infected sheep at the second day of bacteremia (C, E, and G). Neutrophils were incubated as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (A) Neutrophil morphology immediately after isolation, with cells showing no morphological features of apoptosis. Neutrophils incubated for 22 h at 37°C in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and l-glutamine only (B and C), while panels D and E also contained PBMC conditioned medium and panels F and G were supplemented with actinomycin D. The results shown are typical of those obtained from six different sheep.

Actinomycin D treatment accelerated apoptosis of control, uninfected sheep neutrophils, but neutrophils isolated from sheep at the peak of infection (second day of bacteremia) were less sensitive to the inhibitory effects exerted by the transcriptional inhibitor. By the fourth day of bacteremia, infected neutrophils had regained their sensitivity to actinomycin D treatment.

Effects of in vivo A. phagocytophilum infection on NADPH oxidase activity.

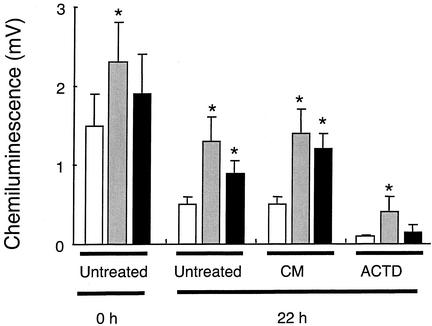

Neutrophils isolated from the blood of healthy sheep could be stimulated by PMA and opsonized zymosan to elicit a respiratory burst, as detected by luminol chemiluminescence (Fig. 5). When these neutrophils were incubated for 22 h in culture and became apoptotic, this ability to generate a respiratory burst decreased, as has previously been shown for human neutrophils (2). Treatment of neutrophils with conditioned medium from PBMC during this 22-h culture did not significantly enhance respiratory burst activity, whereas treatment with actinomycin D (which accelerated apoptosis) resulted in a significant decrease in chemiluminescence.

FIG. 5.

Changes in NADPH oxidase activity of neutrophils isolated from uninfected and A. phagocytophilum-infected sheep. Neutrophils were isolated from the venous blood of sheep prior to infection (□) and on the second (░⃞) and fourth (▪) days of bacteremia. Purified neutrophils were then incubated in RMPI 1640 medium as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Cultures contained no further additions (Untreated), PBMC conditioned medium (CM), or actinomycin D (ACTD). The activity of the NADPH oxidase was then measured after incubation for 0 and 22 h by luminol chemiluminescence after the addition of 0.1 μg of PMA/ml. Values shown are means ± the SD (n = 6), and asterisk indicates values significantly different from the value measured in neutrophils from uninfected sheep (P < 0.02).

Neutrophils isolated from sheep on the second day of bacteremia (peak infection) had rates of PMA-stimulated and opsonized zymosan-stimulated chemiluminescence that were significantly higher than levels seen in control animals (P < 0.01). Indeed, the rates of chemiluminescence seen in neutrophils isolated from sheep at the fourth day of bacteremia were also elevated above rates seen in control, uninfected neutrophils. Addition of conditioned medium from concanavalin A-stimulated PBMCs did not enhance respiratory burst activity more than that seen in A. phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils. Treatment with actinomycin D significantly decreased chemiluminescence in both control, uninfected neutrophils and neutrophils from A. phagocytophilum-infected animals.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here show for the first time that, in vivo, erhlichiosis induces delays in apoptosis in ovine neutrophils. These observations with sheep experimentally infected with A. phagocytophilum confirm data obtained after in vitro infection of human neutrophils with HGE (37). Thus, this process of delayed neutrophil apoptosis after ehrlichiosis would appear to be an important pathological mechanism that the organism employs to ensure its infection and survival within the mammalian host. This in vitro or in vivo delay of apoptosis contrasts with the effects of HGE on a neutrophil-like cell line, HL-60, in which cell cycle arrest and increased apoptosis are seen (5, 21). Thus, infection-induced apoptosis delay is a neutrophil-specific process and not a general consequence of cell infection.

In view of the diverse range of potent antimicrobial processes that it possesses, the neutrophil would appear to be an unlikely target for infection by an intracellular bacterium. However, A. phagocytophilum clearly replicates within neutrophils, as seen by the abundance of morulae seen within cytoplasmic vacuoles of neutrophils (Fig. 4). These morulae arise as a result of intracellular replication of the bacteria. The bacteria must also evade activation of the cytotoxic arsenal of neutrophils. One way in which it does this is via uptake into vacuoles in a process that does not result in granule fusion to form a phagolysosome (18), which would normally discharge the contents of these granules into the bacterium-containing vacuole. Furthermore, bacterium- neutrophil contact (which is a prerequisite to uptake) must also occur via a process that does not activate dormant NADPH oxidase complexes on the plasma membrane. Indeed, it has been shown that HGE downregulates NADPH oxidase activity of human neutrophils via an as-yet-undefined process that probably requires the synthesis by neutrophils of a short-lived inhibitory protein (37).

In our experiments, we show that after in vivo infection of sheep with A. phagocytophilum, the neutrophil respiratory burst is actually elevated above uninfected levels. The reasons for this are unclear, but we have only measured neutrophil function on the second and fourth days of bacteremia. It is possible that neutrophil function at earlier times after infection would be different, but neutrophil infection rates are low before these times. However, preliminary experiments with ovine neutrophils infected in vitro with A. phagocytophilum (unpublished observations) indicate that, like HGE and human neutrophils, the organism can similarly downregulate the activity of the NADPH oxidase within 60 min of addition to neutrophils. This downregulation of oxidase activity has been proposed to occur via the induction of expression of a protein that downregulates NADPH oxidase function. We have previously reported the existence of such a short-lived inhibitor of the NADPH oxidase (28).

In our experiments, dexamethasone and sodium butyrate, which have been shown to delay human neutrophil apoptosis (2, 27), had no significant effects on the apoptosis of sheep neutrophils. Both of these agents delay neutrophil apoptosis via molecular processes that require de novo protein biosynthesis (2). The reason why these agents do not affect apoptosis of sheep neutrophils is unclear, but it is possible that apoptosis control is different in sheep neutrophils. Conditioned medium from concanavalin A-stimulated PBMCs could delay the apoptosis of control sheep neutrophils, presumably via the effects of cytokines (mostly gamma interferon and interleukin-1β) present in this medium. Interestingly, this conditioned medium could not further delay apoptosis of A. phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils, indicating that in these infected cells the survival processes could not be further stimulated by the exogenous cytokines. It will also be of interest to determine whether neutrophil apoptosis is affected after infection of sheep with other bacteria or intracellular parasites. This would indicate if endogenously produced cytokines can alter the kinetics of neutrophil apoptosis ex vivo. Many microbes or their products accelerate neutrophil apoptosis (17, 25, 30, 36), but infection of human neutrophils with Leishmania major has been shown to result in delayed apoptosis of human neutrophils (1).

Identification of the processes by which intracellular bacteria such as A. phagocytophilum and HGE perturb neutrophil function such as respiratory burst activation and apoptosis are clearly important for the molecular pathology of ehrlichiosis. However, these bacteria (or their molecular components that interact with neutrophil receptors) should also provide new experimental tools to dissect the complex intracellular pathways that regulate such important neutrophil functions such as activation of microbial killing pathways and the regulation of cell death and survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom) for generous financial support.

The technical support of Karen Horrocks, Department of Veterinary Pathology, is gratefully acknowledged.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Aga, E., D. M. Katschinski, G. Van Zandbergen, H. Laufs, B. Hansen, K. Muller, W. Solbach, and T. Laskay. 2002. Inhibition of the spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophil granulocytes by the intracellular parasite Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 169:898-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akgul, C., D. A. Moulding, and S. W. Edwards. 2001. Molecular control of neutrophil apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 487:318-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken, J. S., J. S. Dumler, S. M. Chen, M. R. Eckman, L. L. Van Etta, and D. H. Walker. 1994. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the upper midwest United States: a new emerging species? JAMA 272:212-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee, R., J. Anguita, D. Roos, and E. Fikrig. 2000. Cutting edge: infection by the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis prevents the respiratory burst by downregulating gp91phox1. J. Immunol. 164:3946-3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedner, E., P. Burfeind, T.-C Hseih, J. M. Wu, M. E. Aguero-Rosenfeld, M. R. Melamed, H. W. Horowitz, G. P. Wormser, and Z. Darzynkiewicz. 1998. Cell cycle effects and induction of apoptosis caused by infection of HL-60 cells with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis pathogen measured by flow and laser scanning cytometry. Cytometry 33:47-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brach, M. A., S. de Vos, H.-J. Gruss, and F. Hermann. 1992. Prolongation of survival of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils by granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor is caused by inhibition of programmed cell death. Blood 80:2920-2924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, S.-M., J. S. Dumler, J. S. Bakken, and D. H. Walker. 1994. Identification of granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. Immunol. 32:589-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colotta, F., F. Re, N. Polentarutti, S. Sozanni, and A. Mantovani. 1992. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood 80:2012-2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox, G. 1995. Glucocorticoid treatment inhibits apoptosis in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 154:4710-4725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies, B., and S. W. Edwards. 1992. Chemiluminescence of human bloodstream monocytes and neutrophils: an unusual oxidant(s) generated by monocytes during the respiratory burst. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 7:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumler, J. S., A. F. Barbet, C. P. J. Bekker, G. A. Dasch, G. H. Palmer, S. C. Ray, Y. Rikihisa, and F. R. Rurangirwa. 2001. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and “HGE agent”as synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 51:2145-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards, S. W. 1995. Cell signalling by integrins and immunoglobulin receptors in primed neutrophils. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:362-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards, S. W., and M. B. Hallett. 1997. Seeing the wood for the trees: the forgotten role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol. Today 18:320-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards, S. W. 1994. Biochemistry and physiology of the neutrophil. Cambridge University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 15.Edwards, S. W. 1987. The O2-generating NADPH oxidase of phagocytes: structure and methods of detection. Methods Companion Methods Enzymol. 9:563-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards, S. W. 1987. Luminol- and lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence of neutrophils: role of degranulation. J. Clin. Lab. Immunol. 22:35-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelich, G., M. White, and K. L. Hartshorn. 2002. Role of the respiratory burst in co-operative reduction in neutrophil survival by influenza A virus and Escherichia coli. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:484-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gocke, H., G. Ross, and Z. Woldehiwet. 1999. Inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion in ovine polymorphonuclear leucocytes by Ehrlichia (Cytoecetes) phagocytophila. J. Comp. Pathol. 120:369-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman, J. L., C. Nelson, B. Vitale, J. E. Madigam, J. S. Dumler, T. J. Kurtti, and U. G. Munderloh. 1996. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon, W. S., A. Brownlee, D. R. Wilson, and L. MacLeod. 1932. Tick-borne fever (a hitherto undescribed disease of sheep). J. Comp. Pathol. 45:301-312. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh, T.-C., M. E. Aguero-Rosenfeld, J. M. Wu, C. Ng, N. A. Papanikolaou, S. A. Varde, I. Schwartz, J. G. Pizzolo, M. Melamed, H. W. Horowwitz, R. B. Nadelman, and G. P. Wormser. 1997. Cellular changes and induction of apoptosis in human promyelocytic HL-60 cells infected with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 232:298-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, A., M. K. B. Whyte, and C. Haslett. 1993. Inhibition of apoptosis and prolongaton of neutrophil functional longevity by inflammatory mediators. J. Leukoc. Biol. 54:283-289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mott, J., and Y. Rikihisa. 2000. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits superoxide anion generation by human neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 68:6697-6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moulding, D. A., J. A. Quayle, C. A. Hart, and S. W. Edwards. 1998. Mcl-1 expression in human neutrophils: regulation by cytokines and correlation with cell survival. Blood 92:2495-2502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perskvist, N., M. Long, O. Stendahl, and L. Zheng. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes apoptosis in human neutrophils by activating caspase-3 and altering expression of Bax/Bcl-xL via an oxygen-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 168:6358-6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savill, J. S., A. H. Wyllie, J. E. Henson, M. J. Walport, P. M. Henson, and C. Haslett. 1989. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 83:865-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stringer, R. E., C. A. Hart, and S. W. Edwards. 1996. Sodium butyrate delays neutrophil apoptosis: role of protein biosynthesis in neutrophil survival. Br. J. Haematol. 92:169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stringer, R. E., and S. W. Edwards. 1995. Potentiation of the respiratory burst of human neutrophils by cycloheximide: regulation of reactive oxidant production by a protein(s) with rapid turnover? Inflamm. Res. 44:158-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuomi, J. 1967. Experimental studies on bovine fever. I. Clinical and haematological data, some properties of the causative agent and homologous immunity. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 70:577-589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Usher, L. R., R. A. Lawson, I. Geary, C. J. Taylor, C. D. Bingle, G. W. Taylor, and M. K. Whyte. 2002. Induction of neutrophil apoptosis by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin pyocyanin: a potential mechanism of persistent infection. J. Immunol. 168:1861-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whyte, M. K., J. Savill, L. C. Meagher, A. Lee, and C. Haslett. 1997. Coupling of neutrophil apoptosis to recognition by macrophages: coordinated acceleration by protein synthesis inhibitors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 62:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woldehiwet, Z. 1987. The effects of tick-borne fever on some functions of polymorphonuclear cells of the sheep. J. Comp. Pathol. 97:481-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woldehiwet, Z., and G. R. Scott. 1993. Tick-Borne (Pasteur) Fever, p. 233-254. In Z. Woldehiwet and M. Ristic (ed.), Rickettsial and chlamydial diseases of domestic animals. Pergamon Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 34.Woldehiwet, Z., S. D. Carter, and C. Dare. 1991. Purification of Cytoecetes phagocytophila, the causative agent of tick-borne fever, from infected ovine blood. J. Comp. Pathol. 105:431-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woldehewit, Z., H. Scaife, C. A. Hart, and S. W. Edwards. Purification of ovine neutrophils and eosinophils: Anaplasma phagocytophilum affects neutrophil density. J. Comp. Pathol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Yamamoto, A., S. Taniuchi, S. Tsuji, M. H. Kobayashi, and Y. Kobayashi. 2002. Role of reactive oxygen species in neutrophil apoptosis following ingestion of heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 129:479-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshie, K., H.-Y. Kim, J. Mtt, and Y. Rikihisa. 2000. Intracellular infection by the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits human neutrophil apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 68:1125-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]