Abstract

An open reading frame (ORF), US28, with homology to mammalian chemokine receptors has been identified in the genome of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). Its protein product, pUS28, has been shown to bind several human CC chemokines, including RANTES, MCP-1, and MIP-1α, and the CX3C chemokine fractalkine with high affinity. Addition of CC chemokines to cells expressing pUS28 was reported to cause a pertussis toxin-sensitive increase in the concentration of cytosolic free Ca2+. Recently, pUS28 was shown to mediate constitutive, ligand-independent, and pertussis toxin-insensitive activation of phospholipase C via Gq/11-dependent signaling pathways in transiently transfected COS-7 cells. Since these findings are not easily reconciled with the former observations, we analyzed the role of pUS28 in mediating CC chemokine activation of pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins in cell membranes and phospholipase C in intact cells. The transmembrane signaling functions of pUS28 were studied in HCMV-infected cells rather than in cDNA-transfected cells. Since DNA sequence analysis of ORF US28 of different laboratory and clinical strains had revealed amino acid sequence differences in the amino-terminal portion of pUS28, we compared two laboratory HCMV strains, AD169 and Toledo, and one clinical strain, TB40/E. The results showed that infection of human fibroblasts with all three HCMV strains led to a vigorous, constitutively enhanced formation of inositol phosphates which was insensitive to pertussis toxin. This effect was critically dependent on the presence of the US28 ORF in the HCMV genome but was independent of the amino acid sequence divergence of the three HCMV strains investigated. The constitutive activity of pUS28 is not explained by expression of pUS28 at high density in HCMV-infected cells. The pUS28 ligands RANTES and MCP-1 failed to stimulate binding of guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thiotriphosphate to membranes of HCMV-infected cells and did not enhance constitutive activation of phospholipase C in intact HCMV-infected cells. These findings raise the possibility that the effects of CC chemokines and pertussis toxin on G protein-mediated transmembrane signaling previously observed in HCMV-infected cells are either independent of or not directly mediated by the protein product of ORF US28.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a member of the β-herpesvirus family, is a slowly growing virus which causes severe birth defects and a wide spectrum of disorders in older children and adults. While HCMV infections of immunocompetent individuals are usually asymptomatic, HCMV infection of immunocompromised patients can result in disseminated disease characterized by fever and leukopenia, hepatitis, pneumonitis, esophagitis, gastritis, colitis, and retinitis (62). HCMV is one of several related species-specific viruses that cause similar diseases in various animals. In vivo, HCMV appears to replicate in a variety of cell types, including fibroblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells (75). HCMV has evolved several mechanisms to evade detection by the host immune system (47) and can latently persist in the host lifelong.

HCMV infection has long been known to be associated with changes in the activity of many cellular signaling pathways (reviewed in references 3 and 29). The cellular responses triggered by HCMV infection can be subdivided into changes emerging within minutes after the initial contact between virus and host cell, likely to be caused by the binding of the virus to and its passage through the host cell plasma membrane, and changes requiring cellular and/or viral gene expression. Increased hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate by phospholipase C into the intracellular second messengers d-myo-inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate and sn-1,2-diacyglycerol is among the earliest responses, occurring within minutes after the exposure of cells to HCMV (81). d-myo-Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate causes the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores, whereas sn-1,2-diacyglycerol activates protein kinase C. There is no requirement of infectious virus for the immediate, plasma membrane-related events, since they are not inhibited by inactivation of the virus with UV light or by inhibition of protein or RNA synthesis (3). Alterations observed after the initiation of cellular and/or viral gene expression include sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) (67), changes in the host cell cycle (40), and modulation of interferon signaling (29).

A series of recent observations suggests that, among other viral and cellular factors, chemokines and their receptors play important roles in the subversion of the host cell immune system by activating and modulating host cell signaling pathways (49, 58, 83). Chemokines constitute a growing family of small cytokines involved in regulating endothelial adhesion of leukocytes and their transendothelial migration into inflamed tissue (51, 56, 69). Transmembrane signaling of chemokines is mediated by chemokine receptors, which are members of the superfamily of heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptors (57). In most cell types, chemokine receptors are coupled to pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G proteins, which regulate the activities of a number of intracellular signal transduction components, including phospholipase C-β (PLC-β) and inositol phospholipid 3-kinase-γ (79).

Interestingly, herpesviruses, including HCMV, have adopted genes coding for homologues of mammalian chemokines and chemokine receptors (58, 68). Four open reading frames (ORFs) with homology to mammalian chemokine receptors have been identified in the genome of HCMV: US27, US28, UL33, and UL78 (68). No viral or cellular ligands have yet been described for the proteins encoded by US27, UL33, and UL78. In contrast, the protein product of ORF US28, pUS28, has been shown to bind a number of human CC chemokines, including regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), and the CX3C chemokine fractalkine, with high affinity (9, 11, 31, 44, 45, 59, 82). Furthermore, addition of CC chemokines to cells expressing pUS28 has been shown to cause increases in the concentration of cytosolic free Ca2+ (9, 31, 82) and to promote directed migration of smooth muscle cells (78).

Very recently, pUS28 was shown to mediate constitutive, PTX-insensitive activation of phospholipase C via Gq/11-dependent signaling pathways in a ligand-independent manner in transiently transfected COS-7 cells (19). Interestingly, both RANTES and MCP-1 had no effect on this activity. This finding is not easily reconciled with earlier findings showing stimulatory effects of CC chemokines, including RANTES and MCP-1, on the concentration of cytosolic free Ca2+ in transfected as well as HCMV-infected cells (9, 31, 82) and demonstrating that this effect was blocked by PTX in HCMV-infected cells (9). We therefore set out to analyze the role of pUS28 in mediating CC chemokine activation of PTX-sensitive G proteins in cell membranes and phospholipase C in intact cells in more detail. Since the ORF of HCMV encodes >200 unique proteins with mostly unknown functions (61) and since HCMV infection of human cells has been shown to result in up- or downregulation of >1,400 cellular mRNAs during a 48-h time course after infection (16), the products of which could conceivably influence the function of pUS28 during natural infection, we sought to determine the transmembrane signaling functions of pUS28 in HCMV-infected rather than transfected cells. Finally, the fact that DNA sequence analysis of ORF US28 in different laboratory and clinical strains has revealed amino acid sequence differences located predominantly, but not exclusively, in the amino-terminal, extracellular portion of pUS28 prompted us to analyze and compare two laboratory HCMV strains, AD169 and Toledo, and one clinical strain, TB40/E.

Our present results demonstrate that infection of human fibroblasts with the HCMV laboratory strains AD169 and Toledo and the clinical isolate TB40/E leads to a vigorous, constitutively enhanced formation of inositol phosphates. This effect is critically dependent on the presence of the US28 ORF in the HCMV genome but independent of amino acid sequence divergence of the three HCMV strains investigated. The pUS28 ligands RANTES and MCP-1 failed to stimulate binding of [35S]GTP[S] to membranes of HCMV-infected cells and did not enhance constitutive activation of phospholipase C in intact HCMV-infected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

PTX was obtained from List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, Calif.). Cell culture media and supplements were purchased from Gibco Invitrogen Corporation (Karlsruhe, Germany), Biochrom (Berlin, Germany), or PAA Laboratories (Cölbe, Germany). 125I-RANTES (2,200 Ci/mmol), guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thiotriphosphate) ([35S]GTP[S]) (1,250 Ci/mmol), and d-myo-[2-3H]inositol (22 Ci/mmol; NET-114A) were purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences (Boston, Mass.). The human chemokines RANTES and MCP-1 and the CX3C chemokine domain of human fractalkine (residues 1 to 76) were obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, N.J.). l-α-Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) was purchased from Sigma (Munich, Germany). Purified mouse monoclonal anti-human RANTES antibody (clone 21445.1; MAB278) and anti-human MCP-1 antibody (500-M71) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.) and Peprotech, respectively.

Cell culture.

A fibroblast cell line established from human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) was maintained in minimum essential medium with Earle's salts (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco), 10 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, and minimum essential medium nonessential amino acids (1×) (Biochrom). The cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 and were used between passages 14 and 16. HFF were infected 24 h after being seeded with either the HCMV laboratory strain AD169 or Toledo, the clinical isolate TB40/E, or mutants of AD169 lacking either US27 (AD169-ΔUS27) or US28 (AD169-ΔUS28). The endothelial-cell-adapted strain TB40/E (76) was a kind gift from Christian Sinzger, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, and AD169-ΔUS27 virus (11) was kindly provided by Thomas R. Jones (Wyeth-Ayerst Reseach, Pearl River, N.Y.). The HCMV strains AD169 and Toledo were obtained from Ulrich H. Koszinowski, University of Munich, Munich, Germany. For characterization of the transcription of US28 during viral infection, the cells were treated with 250 μg of phosphonoacetic acid (PAA)/ml, an inhibitor of herpesvirus DNA polymerase.

Construction of the recombinant HCMV AD169-ΔUS28.

The bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) mutagenesis technology (12, 53) was used to generate a recombinant virus with a deletion in the US28 gene. To generate the recombination shuttle plasmid pSTΔUS28, cosmid pCM1035 was used, containing the HindIII fragments I, A, H, and V of HCMV AD169 cloned in pHC79 after partial cleavage of the viral DNA with HindIII (27). A fragment, encompassing nucleotides (nt) 216,298 to 222,296 of the published sequence (EMBL/GenBank accession no. X17403 [20]) and including the ORFs US27, US28, and US29, as well as parts of US26 and US30, was prepared from pCM1035 by BamHI digestion, blunt ended with Klenow enzyme, and inserted into the SmaI site of pUC19. A single guanine nucleotide is missing in position 220,095 of the AD169 nucleotide sequence deposited in the EMBL/GenBank data libraries. We have confirmed this difference for the AD169 strain used in this study. Nevertheless, the nucleotide numbering used here corresponds exactly to that of the sequences deposited in the data libraries, thus ignoring the existence of the inserted nucleotide. Nucleotides 219,431 to 220,161, encoding residues 78 to 321 of the US28 polypeptide (354 residues), were released from this plasmid by partial digestion with NotI and KpnI. The remaining sequence was blunt ended and religated, resulting in pUC-ΔUS28. The insert of plasmid pUC-ΔUS28 was then isolated by partial digestion with BamHI and KpnI and inserted into the shuttle plasmid pST76-K (64) to generate pSTΔUS28. Mutagenesis of the HCMV BAC plasmid pHB5 (12) with the shuttle plasmid pSTΔUS28 was performed by a two-step replacement strategy using homologous recombination in the E. coli strain CBTS (42), already containing the HCMV BAC plasmid as described previously (53), resulting in the BAC plasmid pHCMV-ΔUS28. For reconstitution of viral progeny, HFF were transfected with 1.5 μg of pHCMV-ΔUS28 by electroporation. After electroporation, the fibroblasts were propagated for 14 days in 10-cm-diameter culture dishes and then transferred to T75 flasks. After the appearance of virus-associated cytopathic effects, supernatant medium was removed by aspiration and used for infection of fibroblasts and generation of virus stocks. Virus titers were determined prior to and at the time of inoculation (0 days postinfection [p.i.]) by counting viral plaques grown in HFF monolayers and are expressed as multiplicities of infection (MOI) in PFU inoculated per cell.

RNA analysis.

HFF were infected at an MOI of 1 with either wild-type or mutant HCMV. At various times p.i., total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), fractionated (10 μg/sample) by denaturing formaldehyde agarose (1% [wt/vol]) gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane (Zeta-Probe GT; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany), and hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe corresponding either to the deleted NotI/KpnI fragment of ORF US28 (nt 219,426 to 220,161) or to ORF US27 (nt 217,904 to 218,992). To assess the quality of the analyzed RNA, the blot was stripped and rehybridized with radiolabeled cDNA encoding rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (28).

Radioligand binding.

HFF were seeded in 24-well plates and infected as described above. At the indicated times, the medium was removed by aspiration, and the cells were incubated for 15 min at 4°C in the absence or presence of unlabeled chemokines in buffer (250 μl/well) containing 25 mM HEPES- NaOH, pH 7.0, and 1 mg of bovine serum albumin (A-4503; Sigma)/ml. 125I-RANTES diluted in water was added in a volume of 2.5 μl to a final concentration of 28 pM, and the incubation was continued for 225 min at 4°C. The binding reaction was terminated by washing the cells two times, each time at 4°C with 500 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 mM KH2PO4 and 150 mM NaCl, adjusted to pH 7.8 with NaOH. The washed cells were lysed with 0.5 ml of 500 mM NaOH, and the radioactivity contained in the cell lysates was measured in a gamma counter.

Membrane preparation.

HFF were grown in six-well plates and infected with HCMV as described above. After 48 h, the infected cells were harvested by scraping them into PBS, washed two times at room temperature with 2 ml of PBS each time, and resuspended at 1 ml per dish of ice-cold lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 3 μM GDP, 2 μg of soybean trypsin inhibitor/ml, 1 μM pepstatin, 1 μM leupeptin, 100 μM phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg of aprotinin/ml. The cells were homogenized by forcing the suspension six times through a 0.5- by 23-mm needle attached to a disposable syringe. The lysate was centrifuged at 2,450 × g for 45 s to remove unbroken cells and nuclei. A crude membrane fraction was isolated from the resulting supernatant by centrifugation at 26,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was rinsed with 300 μl of lysis buffer, resuspended in 300 μl of fresh lysis buffer, and stored at −20°C.

[35S]GTP[S] binding.

Binding of [35S]GTP[S] to membranes of HCMV-infected HFF was assayed as described previously (55). In brief, membranes (10 μg of protein/sample) were incubated for 60 min at 30°C in the absence or presence of 200 nM RANTES or 10 μM LPA in a mixture (100 μl) containing 62.5 mM triethanolamine-HCl, pH 7.4, 1.25 mM EDTA, 6.25 mM MgCl2, 95 mM NaCl, 3.75 μM GDP, and 0.34 nM [35S]GTP[S] (1,250 Ci/mmol). The incubation was terminated by rapid filtration through 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membranes (Advanced Microdevices, Ambala Cantonment, India). The membranes were washed and dried, and the retained radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Nonspecific binding was defined as the binding not competed for by 60 μM unlabeled GTP[S].

Inositol phosphate formation.

HFF were seeded in six-well plates and infected with HCMV as described above. Five hours after infection, the medium was removed by aspiration and the cells were labeled for 48 h in fresh inositol-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (11963-022; Gibco) without serum supplemented with 1× each of the following (all obtained as 100× stocks from Gibco): l-glutamine, l-cysteine, l-leucine, l-methionine, l-arginine, d-glucose, and NaH2PO4, and containing 10 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin (from PAA)/ml, and 3 μCi of d-myo-[2-3H]inositol/ml. Subsequently, the labeling medium was aspirated and the cells were washed twice, each time with 2 ml of prewarmed (37°C) DMEM without supplements, and incubated for 10 min in 1 ml of the same medium supplemented with 10 mM LiCl/well at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Where indicated, chemokines were added to a final concentration of 100 nM, and the incubation was continued for the specified time periods. The incubation was stopped by aspirating the supernatant medium and washing the cells twice, each time with 2 ml of prewarmed (37°C) 0.2-g/liter EDTA in PBS (15040-033; Gibco)/well. The cells were detached by incubation in 1 ml of prewarmed nonenzymatic cell dissociation solution (C-5914; Sigma)/well for 1 min at 37°C. Inositol phosphates were extracted from the cells according to the method of Cockcroft et al. (22), with slight variations. In brief, 1.5 ml of a mixture of chloroform and methanol (1:2 by volume) was added to 1 ml of the detached cell suspension. The samples were vigorously mixed and incubated for 10 min at room temperature prior to the addition of 0.5 ml of chloroform and centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min at room temperature to accelerate phase separation. An aliquot (1.6 ml) of the aqueous (upper) phase was applied to columns of Dowex 1 by 8 resin (0.8 ml; 100 to 200 mesh; Cl− form) (Supelco, Bellefonte, Pa.), which had been converted to the formate form as described by Camps et al. (18). Inositol, glycerophosphoinositol, and inositol phosphates were eluted as described by Camps et al. (18). The samples (3 ml each) were supplemented with 15 ml each of scintillation fluid (Quicksafe A; Zinser Analytic, Frankfurt, Germany), and the radioactivity was quantified by liquid scintillation counting.

Miscellaneous.

The radiolabeled cDNA probes were prepared using Ready-To-Go DNA Labeling Beads (−dCTP) (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany). Northern blots were hybridized with the radiolabeled probes as described previously (71). DNA was sequenced on an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, FS (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). Protein concentrations were determined according to the method of Bradford (15) using bovine immunoglobulin G as a standard.

RESULTS

Construction of the deletion mutant HCMV AD169-ΔUS28.

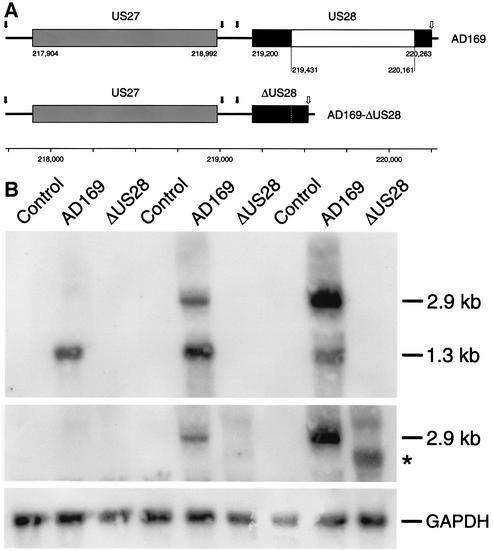

To analyze the function of the protein encoded by US28 in HCMV-infected cells, a US28-deficient variant of HCMV AD169 (AD169-ΔUS28) was generated by mutagenesis of the AD169 genome as infectious BAC in Escherichia coli (12, 53). To this end, the nucleotide sequence of US28 encoding residues 78 to 321 of pUS28 was deleted by restriction endonuclease digestion (Fig. 1A). The recombinant virus AD169-ΔUS28 was reconstituted in HFF. The time course of the expression of the mRNAs encoding US27 and US28 in infected HFF was determined by Northern blotting (Fig. 1B). As previously described (86), transcription of US27 and US28 gives rise to two overlapping 3′-coterminal transcripts with sizes of ∼2.9 and 1.3 kb. The 1.3-kb mRNA encodes pUS28, whereas the 2.9-kb mRNA represents a bicistronic transcript encoding both pUS27 and pUS28. The blot was probed either with the genomic fragment deleted in AD169-ΔUS28, a genomic fragment encoding pUS27, or cDNA encoding GAPDH. In HCMV AD169-infected cells, expression of the 1.3-kb mRNA was evident 24 h p.i., increased to a maximum 48 h p.i., and decreased at subsequent times. Expression of the 2.9-kb bicistronic mRNA was detected 48 h p.i. and was maximal 72 h p.i. No mRNA hybridizing with the fragment encoding pUS28 was detected, and the size of the bicistronic mRNA was reduced to an extent corresponding closely to the size of the deletion in cells infected with AD169-ΔUS28. Thus, transcripts encoding pUS28 are absent in cells infected with AD169-ΔUS28. Propagation of the recombinant ΔUS28 virus in HFF also revealed that the US28 gene product was not essential for virus growth in tissue culture, as the titers of wild-type and mutant virus stocks produced by infection of HFF were similar (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Construction of the deletion mutant HCMV AD169-ΔUS28. (A) Schematic representation of the protocol. The region extending from the putative TATA box located in the 5′ region of US27 to the putative site of polyadenylation in the 3′ region of US28 is shown (84, 87). The coding regions of US27 and US28 are shown as horizontal bars. The putative TATA boxes and the polyadenylation signal are marked by solid and open arrows, respectively. The noncoding region between the coding regions of US27 and US28 lacks a polyadenylation signal (87). Nucleotides 219,431 to 220,161 of US28 were removed from a plasmid carrying the ORFs US27, US28, and US29, as well as parts of US26 and US30 of HCMV AD169, resulting in an in-frame deletion of residues 78 to 321 of pUS28. Prediction of the transmembrane regions of pUS28 according to the method of Baldwin et al. (6) (not shown) suggests that the residual ΔUS28 protein, if expressed, consists of the extracellular amino terminus, the first transmembrane domain, the first intracellular loop, 8 of 18 residues constituting the second transmembrane domain, and 33 of 62 residues constituting the intracellular carboxyl-terminal domain. It is unlikely that the first intracellular loop and the distal part of the carboxyl terminus of G protein-coupled receptors are involved in G protein activation (32, 48). The nucleotide numbering corresponding to EMBL/GenBank accession no. X17403 is shown (see Materials and Methods for details). (B) Expression of mRNAs encoding pUS27 and/or pUS28 in HCMV-infected fibroblasts. HFF were infected with either wild-type HCMV AD169 or AD169-ΔUS28. Total RNA was prepared from the cells 24, 48, and 72 h p.i., fractionated (10 μg/lane) by denaturating formaldehyde-agarose (1% [wt/vol]) gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with radiolabeled cDNA probes corresponding either to the deleted NotI/KpnI fragment of ORF US28 (nt 219,426 to 220,161) (top), to ORF US27 (nt 217,904 to 218,992) (middle), or to rat GAPDH (bottom). The positions of the bicistronic transcript encoding both pUS27 and pUS28 (2.9 kb), the transcript encoding pUS28 (1.3 kb), the bicistronic transcript carrying the deletion in the US28 coding region (asterisk), and the mRNA encoding GAPDH (GAPDH) are indicated.

Binding of chemokines to HCMV-infected HFF.

DNA sequencing of the US28 ORFs of the HCMV strains AD169, Toledo, and TB40/E revealed differences in several positions. All three ORFs carried a nucleotide insertion at position 220,095, resulting in a frame shift in the carboxyl terminus at amino acid 299 that has been reported before for ORF US28 of the Towne strain of HCMV (59). While the sequence of ORF US28 of the AD169 strain used here was otherwise identical to the sequence deposited in the data libraries, the ORF of Toledo revealed nucleotide differences which alter the amino acid sequence in two positions, D19A and D170N. The amino acid sequence of ORF US28 of TB40/E differs from that of ORF US28 of AD169 in six positions: A8T, D15E, E18L, D19G, V23T, and I49V.

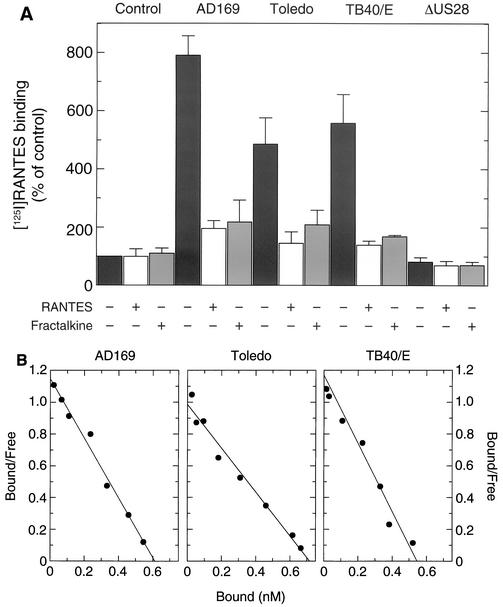

Since most of these amino acid differences are located in the extracellular amino-terminal portion of pUS28, a region known to be critically involved in mediating ligand recognition and interaction of chemokine receptors (23), we determined whether these differences have an impact on ligand binding and/or transmembrane signaling of pUS28 encoded by the HCMV strains AD169, Toledo, and, TB40/E. To this end, we analyzed the binding of the radiolabeled CC chemokine 125I-RANTES (28 pM) to HFF infected with the three HCMV strains at the same MOI. Uninfected HFF cells and cells infected with AD169-ΔUS28 were analyzed for comparison. Figure 2A shows that HFF infected with the three HCMV variants displayed high-affinity binding of 125I-RANTES, whereas no binding was observed for uninfected and AD169-ΔUS28-infected cells. Addition of both unlabeled RANTES and unlabeled fractalkine (10 nM each) caused a marked, similarly sized reduction of 125I-RANTES binding consistent with the known ligand binding specificity of pUS28 in transfected cells (44, 59), demonstrating that 125I-RANTES binding to HCMV-infected HFF was specific. Although the amount of 125I-RANTES was ∼38 and 28% lower in cells infected with HCMV Toledo and HCMV TB40/E than in cells infected with AD169 in the experiment shown in Fig. 2A, this difference was not consistently observed upon analyzing and comparing different batches of the three HCMV strains (cf. Fig. 2B). To determine whether the amino-terminal differences of pUS28 caused an alteration of the affinity of the pUS28-125I-RANTES interaction, 125I-RANTES saturation binding experiments were performed on HFF infected with HCMV AD169, Toledo, and TB40/E at the same MOI. Figure 2B shows that transformation of the binding data according to the method of Scatchard (72) resulted in linear plots, suggesting the existence of a single class of binding sites in all three cases. The equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) of 125I-RANTES binding determined for pUS28 of the three HCMV strains were very similar, ranging from 0.47 to 0.73 nM. Taken together, these results show that specific binding of 125I-RANTES to HCMV-infected HFF is dependent on pUS28 and that the differences in the amino acid sequences of the pUS28 proteins encoded by the three HCMV strains apparently do not affect 125I-RANTES binding to pUS28 in HCMV-infected cells.

FIG. 2.

Binding of 125I-RANTES to HCMV-infected human fibroblasts. (A) Specificity of 125I-RANTES binding. HFF were infected as indicated either with the laboratory HCMV strains AD169 and Toledo, the clinical isolate TB40/E, or the deletion mutant AD169-ΔUS28. Uninfected cells (Control) were analyzed for comparison. The cells were incubated with 28 pM 125I-RANTES. The incubation was performed in the absence (−) or presence (+) of unlabeled RANTES or fractalkine (both at 10 nM) to discriminate specific from nonspecific binding. 125I-RANTES binding is given as a percentage of the binding to uninfected cells. The results correspond to the means plus standard deviations of triplicate determinations. (B) 125I-RANTES saturation binding. HFF were infected as indicated with the HCMV strains AD169, Toledo, or TB40/E. The infected cells were incubated with 28 pM 125I-RANTES in the absence or presence of unlabeled RANTES (10 pM to 10 nM). Uninfected cells were incubated in parallel with 28 pM 125I-RANTES in the absence of unlabeled RANTES to determine the amount of nonspecific binding. The experimental data were transformed according to the method of Scatchard (72) and subjected to linear regression analysis. The equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) were 0.53, 0.73, and 0.47 nM, and the maximum numbers of binding sites were 612, 715, and 544 pM, corresponding to 1.5 × 106, 1.8 × 106, and 1.4 × 106 binding sites/cell for cells infected with AD169, Toledo, and TB40/E, respectively.

Receptor-mediated stimulation of [35S]GTP[S] binding.

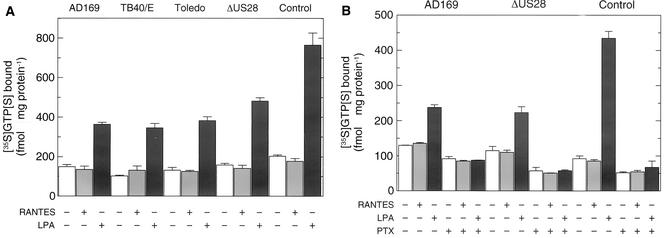

To address the question of whether agonist occupancy of pUS28 caused receptor-mediated stimulation of PTX-sensitive heterotrimeric G proteins in membranes of HCMV-infected HFF, binding of [35S]GTP[S] to these membranes was determined in the absence or presence of RANTES (200 nM) or LPA (10 μM), a known activator of PTX-sensitive heterotrimeric G proteins in primary human fibroblasts (63). Membranes of uninfected HFF were analyzed for comparison. Figure 3A shows that LPA caused a considerable increase in [35S]GTP[S] binding, which was ∼2.5- to 3-fold in HFF infected with wild-type AD169, TB40/E, Toledo, and AD169-ΔUS28 and ∼4-fold in uninfected HFF. Surprisingly, RANTES (200 nM) had no effect on [35S]GTP[S] binding to membranes of infected and uninfected cells. Likewise, MCP-1 (200 nM) and fractalkine (200 nM) were ineffective in this respect (not shown). Treatment of uninfected and AD169-infected cells with PTX for the last 16 h of the infection protocol caused a marked reduction of the effect of LPA on [35S]GTP[S] binding to membranes of these cells (Fig. 3B), strongly supporting the notion that LPA-mediated binding of [35S]GTP[S] reflects activation of PTX-sensitive Gi/o proteins in HFF cell membranes. Note that PTX caused a reduction of [35S]GTP[S] binding even in the absence of receptor ligands and in the presence of RANTES in membranes of infected and uninfected cells. The effects of PTX on functions of heterotrimeric G proteins in membrane preparations in the absence of receptor agonists have previously been attributed to the presence of unoccupied, but nevertheless active, G protein-coupled receptors (33).

FIG. 3.

Agonist-stimulated binding of [35S]GTP[S] to membranes of HCMV-infected human fibroblasts. (A) HFF were infected with the indicated strain of wild-type HCMV (AD169, TB40/E, or Toledo) or AD169-ΔUS28. Uninfected cells (Control) were analyzed for comparison. The cells were homogenized, and aliquots of the particulate fractions prepared from the postnuclear supernatants (10 μg of protein/sample) were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 200 nM RANTES or 10 μM LPA with 0.34 nM [35S]GTP[S]. The samples were analyzed for bound [35S]GTP[S] by rapid filtration and scintillation counting. (B) Effect of PTX on agonist-stimulated binding of [35S]GTP[S]. HFF were infected with wild-type AD169 or AD169-ΔUS28. Uninfected cells (Control) were analyzed for comparison. The cells were pretreated as indicated for 16 h by incubation with PTX (100 ng/ml) or carrier. The cells were then homogenized and subjected to subcellular fractionation. Binding of [35S]GTP[S] to the particulate fractions was determined as described for panel A. The results correspond to the means plus standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Inositol phosphate production.

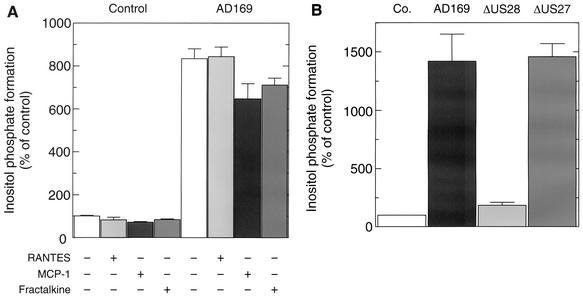

The next experiments were designed to examine whether pUS28 was capable of mediating stimulation of phospholipase C by chemokines in HCMV-infected cells. Uninfected and AD169-infected HFF were labeled with [3H]inositol for the last 43 h of the infection protocol and then analyzed for phospholipase C-mediated formation of [3H]inositol phosphates from the radiolabeled precursor phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in the absence or presence of RANTES, MCP-1, or fractalkine (100 nM each) (Fig. 4A). Most interestingly, we found a marked (∼9-fold) increase of inositol phosphate formation in AD169-infected cells. Importantly, inositol phosphate formation was not further enhanced by RANTES, MCP-1, and fractalkine (100 nM each) but instead remained unchanged by RANTES or was even reduced upon addition of MCP-1 or fractalkine. The degree of this inhibition was ∼15 to 20% when the effects of MCP-1 and fractalkine were assayed for 90 s (Fig. 4A) and was even higher (∼20 to 40%) when MCP-1 or fractalkine was present for 120 min (not shown). Figure 4B illustrates that the marked (∼15-fold) increase of inositol phosphate formation in HCMV-infected cells was strongly dependent on pUS28. Specifically, only a small increase in inositol phosphate formation was observed in HFF infected with AD169-ΔUS28. Conversely, deletion of US27 from the HCMV AD169 genome did not affect the ability of the virus to cause increased inositol phosphate formation. Treatment of HCMV-infected cells with PTX for the last 16 h of the infection protocol resulted in little, if any, change in the increased inositol phosphate formation (results not shown).

FIG. 4.

Stimulation of inositol phosphate formation in HCMV-infected fibroblasts. (A) Effect of chemokines. HFF were infected at an MOI of 1 with HCMV AD169. Five hours after infection, the cells were radiolabeled by incubation in inositol-free medium supplemented with 3 μCi of [3H]inositol/ml. Forty-eight hours after infection, the radiolabeled cells were incubated for 90 s in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 100 nM RANTES, 100 nM MCP-1, or 100 nM fractalkine and then analyzed for the accumulation of [3H]inositol phosphates as described in Materials and Methods. Uninfected cells (Control) were analyzed for comparison. The data are presented as percentages of the [3H]inositol phosphate formation measured in uninfected fibroblasts in the absence of chemokines. (B) Dependence of increased inositol phosphate formation on pUS28. HFF were infected as indicated with HCMV AD169, AD169-ΔUS28, or AD169-ΔUS27. Uninfected control cells (Co.) were analyzed for comparison. Radiolabeling of cells with [3H]inositol and analysis of [3H]inositol phosphate formation was done as described for panel A. The data are presented as percentages of the [3H]inositol phosphate formation measured in uninfected fibroblasts. In both panels, the results correspond to the means plus standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

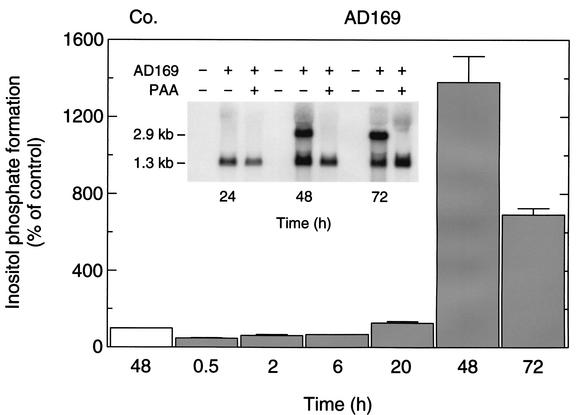

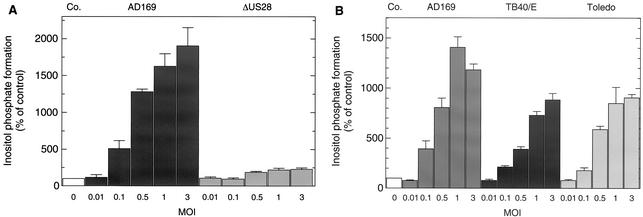

Figures 5 and 6 show that the enhanced inositol phosphate formation was strictly dependent on both the time and the MOI. Specifically, maximal inositol phosphate formation was observed 48 h after the addition of the virus particles to the cells at an MOI of 1 and decreased at later times (Fig. 5). This correlated well with the early-late expression of mRNA encoding pUS28. Thus, both the combined amount of the two 1.3- and 2.9-kb mRNA species (Fig. 5, inset) and the binding of 125I-RANTES (not shown) were maximal 48 h p.i. Treatment of HCMV AD169-infected cells with the herpesvirus polymerase inhibitor PAA prevented the appearance of the 2.9-kb bicistronic transcript (Fig. 5, inset). In additional experiments (not shown), we found that this treatment caused only small, inconsistent changes in inositol phosphate formation observed 48 h p.i. This is consistent with the notion that translation of US28 from the bicistronic transcript contributes to only a minor extent to the enhanced inositol phosphate formation at that time. Figure 6A shows that, at 48 h p.i., maximal inositol phosphate formation was observed at an MOI of 3 (Fig. 6A). Deletion of US28 from HCMV AD169 caused an almost complete loss of the increase in inositol phosphate formation in wild-type HCMV AD169-infected cells (Fig. 6A). The basis of the residual, ∼2-fold increase in inositol phosphate formation is unknown. In additional experiments (not shown), we found that the formation of inositol phosphates increased linearly with time for up to 120 min following the addition of LiCl (10 mM), an agent known to inhibit inositol phosphate monoesterase (8), to the cells. Figure 6B shows that the infection of HFF with the HCMV laboratory strains AD169 and Toledo and the clinical isolate TB40/E at increasing MOI caused similar increases of inositol phosphate formation. The maxima of inositol phosphate formation caused by infection with the three HCMV strains correlated with the levels of 125I-RANTES binding observed for cells infected with virus particles from the same batches (cf. Fig. 2), indicating that the structural differences of the US28 polypeptides encoded by the three HCMV variants do not affect stimulation of inositol phosphate formation.

FIG. 5.

Dependence of increased production of inositol phosphates in HCMV-infected fibroblasts on time of infection. HFF were seeded in six-well plates and infected at an MOI of 1 with HCMV AD169. The cells were then radiolabeled by incubation in inositol-free medium supplemented with 3 μCi of myo-[2-3H]inositol/ml. After the indicated times of infection, inositol phosphate accumulation was measured. The data are presented as percentages of the [3H]inositol phosphate formation measured in uninfected control cells (Co.) at hour 48 of the infection protocol. The results correspond to the means plus standard deviations of triplicate determinations. (Inset) Effect of PAA on the expression of mRNA encoding pUS27 and/or pUS28 in HCMV-infected fibroblasts. HFF were infected with HCMV AD169 and treated (+) with PAA (250 μg/ml). Uninfected cells were analyzed for comparison. Total RNA was prepared from the cells 24, 48, and 72 h p.i., fractionated (10 μg/lane) by denaturating formaldehyde-agarose (1% [wt/vol]) gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with a radiolabeled cDNA probe encoding pUS28. The positions of the bicistronic transcript encoding both pUS27 and pUS28 (2.9 kb) and of the transcript encoding pUS28 (1.3 kb) are indicated.

FIG. 6.

Dependence of increased production of inositol phosphates in HCMV-infected fibroblasts on MOI and HCMV strain. (A) MOI. HFF were infected as indicated at increasing MOI with either wild-type HCMV AD169 or AD169-ΔUS28. After 5 h of infection, the medium was exchanged and the infected cells were labeled for 43 h in inositol-free medium supplemented with 3 μCi of [3H]inositol/ml. Forty-eight hours after infection, inositol phosphate accumulation was measured. The data are presented as percentages of the [3H]inositol phosphate formation measured in uninfected control cells (Co.). (B) Virus strain. HFF were infected as indicated at increasing MOI with HCMV AD169, TB40/E, or Toledo. After 5 h of infection, the medium was exchanged and the infected cells were labeled for 43 h in inositol-free medium supplemented with 3 μCi of [3H]inositol/ml. Forty-eight hours after infection, inositol phosphate accumulation was measured. The data are presented as percentages of the [3H]inositol phosphate formation measured in uninfected control cells (Co.). The results correspond to the means plus standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

Effect of the incubation medium on enhanced inositol phosphate production in HCMV-infected fibroblasts.

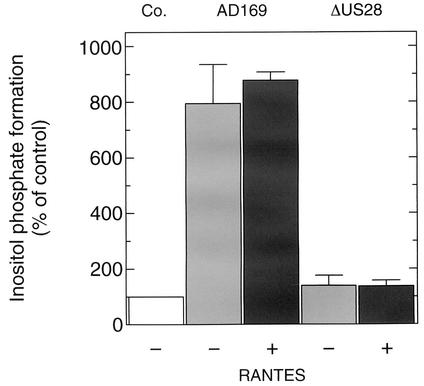

To examine whether the enhanced inositol phosphate formation in HCMV-infected fibroblasts is dependent on a factor(s) present or accumulating in the tissue culture medium during the course of the infection, infected HFF were washed three times with fresh medium at hour 48 of the infection protocol immediately prior to determination of inositol phosphate formation in the absence or presence of 200 nM RANTES. As shown in Fig. 7, a marked enhancement of inositol phosphate formation was evident even in thoroughly washed HFF. Addition of RANTES was without effect. In additional experiments (not shown), we found that the addition of conditioned medium from cells that had been infected with wild-type AD169 or AD169-ΔUS28 to washed, wild-type AD169-infected HFF did not affect inositol phosphate formation. Finally, the addition of an antiserum reactive against human RANTES at a concentration that completely inhibited the binding of 125I-RANTES to HCMV-infected HFF had no effect on inositol phosphate formation. Likewise, addition of an antibody against human MCP-1 was ineffective in this respect. Taken together, these results indicate that enhanced inositol phosphate formation observed in HCMV-infected cells is independent of extracellular factors and, rather, is due to constitutive activity of pUS28.

FIG. 7.

Effect of incubation medium on enhanced inositol phosphate production in HCMV-infected fibroblasts. HFF were seeded in six-well plates and infected with either wild-type AD169 or AD169-ΔUS28. After 5 h of infection, the medium was exchanged and the cells were labeled for 43 h in inositol-free medium supplemented with 3 μCi of [3H]inositol/ml. Thereafter, the medium (1 ml/well) was removed by aspiration, and the remaining cell layer was washed three times with 2 ml of prewarmed DMEM without supplements. Immediately after the addition of fresh medium containing 10 mM LiCl to the washed cells (1 ml/well), the medium was supplemented (+) with RANTES (100 nM final concentration) or carrier. Following incubation for 90 s, inositol phosphate formation was determined. The results correspond to the means plus standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

DISCUSSION

The protein product of US28 has previously been shown to bind CC chemokines and the CX3C chemokine fractalkine, but not CXC chemokines, when expressed as recombinant polypeptide in cDNA-transfected cells (31, 45, 59) or as virus-encoded protein in HCMV-infected human cells (9, 11, 82). Binding of CC chemokines to pUS28 has been shown to correlate with CC chemokine-mediated increases in the concentration of cytosolic free Ca2+ in transfected (31) as well as HCMV-infected (9, 82) cells. In US28 cDNA-transfected human kidney epithelial (HEK293) cells, PTX was found to block the increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration caused by RANTES and MCP-3 (9). In this study, we were unable to detect CC chemokine-mediated changes in [35S]GTP[S] binding to PTX-sensitive G proteins in membranes of HCMV-infected fibroblasts and in the intracellular concentration of free Ca2+ ions in intact HCMV-infected fibroblasts, despite the fact that these cells displayed a marked increase in the number of 125I-RANTES binding sites on their surfaces following infection. Upon examining potential reasons for this apparent discrepancy, we found that infection of HFF with HCMV AD169 caused a striking increase in the formation of inositol phosphates even in the absence of exogenous chemokines.

The enhanced inositol phosphate formation was not observed in AD169 carrying a deletion in the coding region of US28, demonstrating that this response is specifically initiated by the protein product of US28. The enhanced inositol phosphate formation observed in HCMV AD169-infected fibroblasts is not restricted to the specific variant of pUS28 encoded by AD169 but is also observed with the laboratory strain Toledo and the clinical isolate TB40/E. The fact that the levels of inositol phosphate formation were similar suggests that residues in positions 8, 15, 19, 23, 49, and 170 of pUS28 are not critically involved in this function. Recently, differences have been observed in the US28 coding regions of other clinical HCMV isolates (R. Minisini, R. Tulone, S. Gierschik, P. Gierschik, T. Mertens, and B. Moepps, unpublished data). Whether these structural changes affect the ability of pUS28 to mediate enhanced inositol phosphate formation is subject to further investigation.

Infection of fibroblasts with HCMV has been shown to cause an increase in the extracellular concentrations of certain chemokines, e.g., RANTES and MCP-1 (11, 54). Although this increase appeared to be transient and only low levels of the two chemokines were detected in the extracellular medium of HCMV-infected cells at times later than 48 h p.i., we considered the possibility that the increased formation of inositol phosphates in HCMV-infected HFF observed in this study was due to the activity of an autocrine loop made up of the secreted pUS28 ligands RANTES and/or MCP-1 and the cell surface-exposed US28 protein. This seemed a relevant concern, since the expression of mRNAs encoding RANTES and pUS28 is upregulated with similar time courses during HCMV infection of HFF (54). However, enhanced inositol phosphate formation was also observed in cells that had been thoroughly washed, and readdition of conditioned medium did not affect inositol phosphate formation by washed HFF. Furthermore, addition of RANTES- or MCP-1-neutralizing antibodies to the extracellular medium of HCMV-infected cells had no effect on inositol phosphate accumulation. Also pertinent to this issue, a mutant of pUS28 lacking the amino-terminal 21 residues failed to bind 125I-RANTES in transiently transfected COS-7 cells but still constitutively stimulated inositol phosphate formation (results not shown). This observation argues against the possibility that constitutive inositol phosphate formation is due to activation of G proteins by intracellular, agonist-activated pUS28, which would be resistant to washing maneuvers or agonist depletion by extracellular application of antibodies. This possibility seems a relevant one, since pUS28 has been suggested to undergo internalization together with bound ligand (11, 30, 82). Taken together, these findings argue against the possibility that pUS28 is activated by ligands present in the extracellular medium.

Two models, the extended ternary complex model (70) and the cubic ternary complex model (43), are currently used to explain the relationship among the density of constitutively active receptors, the constitutive response, and its sensitivity to receptor agonists. Importantly, both models predict that expression of spontaneously active receptors at very high levels may cause near-maximal or even maximal G protein activation even in the absence of receptor agonists. Under these conditions, the maximal constitutive activity may be similar or even equal to the maximal response produced by a full agonist, while the same receptor may respond to agonists, but may not produce constitutive activity, when expressed at low levels (21, 43). It therefore appeared important to us to consider the possibility that the resistance of pUS28 to stimulation by its ligands RANTES and MCP-1 is the result of very high levels of expressed receptor in infected (this study) or transfected (19) cells. Thus, the cell surface density of 125I-RANTES binding sites was found to be very high in US28 cDNA-transfected cells (∼250,000 binding sites/cell [44]) and was even higher in HCMV-infected cells (≤1.8 × 106 binding sites/cell; this study). Two observations, however, argue against this possibility. First, RANTES (100 nM) had no effect on pUS28-mediated inositol phosphate formation at early times in HCMV infection (12 and 24 h p.i.) (data not shown) and when HFF were infected with HCMV at low MOI (0.01, 0.1, and 0.5) (data not shown). Second, neither RANTES (100 nM) nor MCP-1 (100 nM) caused activation of pUS28 in COS-7 cells transiently transfected with small amounts of US28 cDNA, causing only ∼25% of the maximal constitutive inositol phosphate formation seen upon transfection with a maximally effective amount of the cDNA (not shown). Taken together, these findings not only show that the constitutive activity of pUS28 observed during natural HCMV infections is truly agonist independent but also clearly argue against the notion that this agonist independence is due to overexpression of pUS28 in HCMV-infected or US28 cDNA-transfected cells. According to both the extended ternary complex and the cubic ternary complex models, this would imply that the allosteric constant determining the equilibrium between the pUS28 conformations Ri (inactive) and Ra (active), designated J (70) or L (43), adopts a very high value. This would explain both the high constitutive activity of pUS28 and its resistance to agonist stimulation.

The functional consequences of constitutive inositol phosphate formation in HCMV-infected human cells are unknown, but it is obvious that they are of high interest. Heterologous expression of agonist-activated and/or constitutively active phospholipase C-stimulating receptors, e.g., the mas oncogene product; the serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors; the M1, M3, and M5 subtypes of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors; and certain mutants of the α1B adrenoceptor, has previously been shown to cause transformation of NIH 3T3 and Rat-1 fibroblasts (4, 35, 39, 89). Stimulation of phospholipase C by these receptors is likely to be mediated by members of the PTX-insensitive Gqα subfamily of G protein α subunits. The fact that enhanced inositol phosphate formation in HCMV-infected fibroblasts was largely insensitive to PTX suggests that it was due to pUS28-mediated activation of phospholipase C-β isozymes by one or several members of the Gqα subfamily of G protein α subunits, made up of Gqα, G11α, G14α, and G15/16α (66, 74). Results obtained by Casarosa et al. (19) in transfected COS-7 cells are consistent with this view. Interestingly, microinjection of antibodies against Gqα or against the phospholipase C substrate phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate has been shown to block DNA synthesis and mitogenesis in response to activation of Gqα-coupled bombesin and bradykinin receptors (46, 52). However, ambiguous results have been obtained with regard to the effects of constitutively active members of the Gqα subfamily on cell growth. Specifically, expression of GqαQ209L has been shown to transform NIH 3T3 cells (25, 41). Stable, inducible expression of Gqα in NIH 3T3 cells potentiated platelet-derived growth factor-stimulated mitogenesis in contact-inhibited, confluent fibroblasts (26). On the other hand, several groups observed that stable expression of constitutively active Gqα, G11α, or G16α is growth inhibitory in a number of cell types, including NIH 3T3 cells (88), Swiss 3T3 cells (65), vascular smooth muscle cells (37), human small-cell lung cancer cells (36), and COS-7, as well as CHO, cells (5). In vascular smooth muscle cells, stable expression of Gα16Q212L caused effects that resembled those observed upon prolonged exposure of cells to vasoconstrictors, e.g., hypertrophy and muscle-specific gene expression (37). While the reason for these divergent responses to enhanced expression of activated Gqα proteins are unclear, several possible explanations have been put forward, including differences in the methodology and conditions used to determine cell growth and transformation (26); differences in desensitization of the downstream signal transduction components, e.g., inositol trisphosphate receptors (60); a biphasic concentration response behavior of cell growth upon increasing the cellular levels of activated Gqα proteins (1); or cell-type-specific interaction of constitutively active members of the Gαq family with effectors other than PLC-β isozymes (41). Interestingly, HCMV infection has long been known to stimulate host cell DNA synthesis (2, 77). Recently, it became clear that HCMV infection causes cells to reenter the cell cycle but prevents them from entering S phase, where the synthesis of the cellular genome would compete with that of the virus for the available precursors for DNA replication (40). The contribution of pUS28 to any of these responses is unclear. However, our attempts at generating clones of NIH 3T3 cells stably expressing pUS28 have so far been unsuccessful, suggesting that pUS28 may be growth inhibitory in this cell type.

Little mechanistic information is available on the contribution of the pUS28-mediated activation of phospholipase C to cellular effects other than cell growth. HCMV infection of arterial smooth muscle cells has been shown to constitutively activate cell migration (78). Interestingly, activation of the migratory response was insensitive to PTX but was dependent on MCP-1 produced by the infected cells and secreted into the incubation medium. In the absence of MCP-1, addition of RANTES caused a marked, concentration-dependent increase in smooth muscle cell migration. Importantly, cellular migration induced by HCMV was specifically observed for arterial smooth muscle cells. Neither venous smooth muscle or endothelial cells nor dermal fibroblasts migrated upon HCMV infection. Thus, specific cellular or microenvironmental requirements may have to be fulfilled to allow pUS28 to express its pathophysiologically relevant role. In this context, it is interesting that stable expression of Gα16Q212L has been reported to inhibit agonist-mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+ (36, 37). It is therefore possible that one of the pathophysiological functions of pUS28 is to block the response of HCMV-infected cells to certain Ca2+-mobilizing hormones or cytokines. There are precedents in the literature for this to occur in HCMV-infected cells (38). On the other hand, Gq subfamily-coupled receptors have long been known to enhance the cellular response to activation of other receptors and to participate in this way in the detection of coincident signals (13, 14). For example, type II adenylyl cyclase can integrate regulatory signals transmitted by receptors coupled to Gs and Gq, and responses to extracellular signals acting through these two G proteins are enhanced synergistically by simultaneous signals (50). Along the same lines, the stimulatory effect of constitutively active Gαi2 on ERK2 was synergistically enhanced by constitutively active Gα11 in HEK293T cells (10). Recently, expression of constitutively active mutants of Gαq, Gα16, or Gα14 was shown to permit Gi-coupled receptors to stimulate PLC-β via Gβγ (17). It therefore appears possible that pUS28-activated members of the Gqα subfamily may also render HCMV-infected cells more sensitive to conditional activation by receptors acting through other G proteins, e.g., chemokine receptors acting through PTX-sensitive G proteins. Whether this permissive activity is the molecular basis of the enhanced effects of PTX-sensitive G proteins observed in HCMV-infected cells (9, 73) remains an intriguing question to be clarified by future experimentation.

Our present results demonstrate that infection of human fibroblasts, which are targets for HCMV infection in vivo (75, 80), with the HCMV laboratory strains AD169 and Toledo and the clinical isolate TB40/E leads to a vigorous, constitutively enhanced formation of inositol phosphates. This effect is critically dependent on the presence of the US28 ORF in the HCMV genome. The constitutive activity of pUS28 is not due to ligand-mediated activation of pUS28 and is not explained by expression of pUS28 at high density in HCMV-infected cells. The fact that the pUS28 ligands RANTES and MCP-1 failed to stimulate binding of [35S]GTP[S] to membranes of HCMV-infected cells and did not enhance activation of phospholipase C in intact HCMV-infected cells raises the possibility that the effects of CC chemokines and PTX on G protein-mediated transmembrane signaling previously observed in HCMV-infected cells are either independent of or not directly mediated by the protein product of US28.

While this paper was in preparation, two groups reported that the protein products of the rat and murine CMV ORFs R33 and M33, which are homologous to UL33 of HCMV, caused constitutive activation of the Gq-phospholipase C pathway in transiently transfected COS-7 cells (34, 85). The two proteins appear to play an important role in the dissemination and/or replication of the corresponding viruses in vivo (7, 24).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

The expert technical assistance of Ingrid Büsselmann and Susanne Gierschik is greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, J. W., Y. Sakata, M. G. Davis, V. P. Sah, Y. Wang, S. B. Liggett, K. R. Chien, J. H. Brown, and G. W. Dorn. 1998. Enhanced Gαq signaling: a common pathway mediates cardiac hypertrophy and apoptotic heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10140-10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht, T., M. Nachtigal, S. C. St Jeor, and F. Rapp. 1976. Induction of cellular DNA synthesis and increased mitotic activity in Syrian hamster embryo cells abortively infected with human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 30:167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht, T., M. P. Fons, I. Boldogh, S. AbuBakar, C. Z. Deng, and D. Millinoff. 1991. Metabolic and cellular effects of human cytomegalovirus infection. Transplant. Proc. 23(Suppl. 3):48-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen, L. F., R. J. Lefkowitz, M. G. Caron, and S. Cotecchia. 1991. G-protein-coupled receptor genes as protooncogenes: constitutively activating mutation of the α1B-adrenergic receptor enhances mitogenesis and tumorigenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:11354-11358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Althoefer, H., P. Eversole-Cire, and M. I. Simon. 1997. Constitutively active Gαq and Gα13 trigger apoptosis through different pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24380-24386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin, J. M., G. F. Schertler, and V. M. Unger. 1997. An α-carbon template for the transmembrane helices in the rhodopsin family of G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Mol. Biol. 272:144-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beisser, P. S., C. Vink, J. G. Van Dam, G. Grauls, S. J. Vanherle, and C. A. Bruggeman. 1998. The R33 G protein-coupled receptor gene of rat cytomegalovirus plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of viral infection. J. Virol. 72:2352-2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berridge, M. J., C. P. Downes, and M. R. Hanley. 1989. Neural and developmental actions of lithium: a unifying hypothesis. Cell 59:411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billstrom, M. A., G. L. Johnson, N. J. Avdi, and G. S. Worthen. 1998. Intracellular signaling by the chemokine receptor US28 during human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 72:5535-5544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaukat, A., A. Barac, M. J. Cross, S. Offermanns, and I. Dikic. 2000. G protein-coupled receptor-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation through cooperation of Gαq and Gαi signals. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6837-6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodaghi, B., T. R. Jones, D. Zipeto, C. Vita, L. Sun, L. Laurent, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, J.-L. Virelizier, and S. Michelson. 1998. Chemokine sequestration by viral chemoreceptors as a novel viral escape strategy: withdrawal of chemokines from the environment of cytomegalovirus-infected cells. J. Exp. Med. 188:855-866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borst, E. M., G. Hahn, U. H. Koszinowski, and M. Messerle. 1999. Cloning of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: a new approach for construction of HCMV mutants. J. Virol. 73:8320-8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourne, H. R., K. D. Lustig, Y. H. Wong, and B. R. Conklin. 1992. Detection of coincident signals by G proteins and adenylyl cyclase. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 57:145-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourne, H. R., and R. Nicoll. 1993. Molecular machines integrate coincident synaptic signals. Cell 72(Suppl.):65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Browne, E. P., B. Wing, D. Coleman, and T. Shenk. 2001. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J. Virol. 75:12319-12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan, J. S., J. W. Lee, M. K. Ho, and Y. H. Wong. 2000. Preactivation permits subsequent stimulation of phospholipase C by Gi-coupled receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 57:700-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camps, M., C. F. Hou, K. H. Jakobs, and P. Gierschik. 1990. Guanosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate-stimulated hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in HL-60 granulocytes. Evidence that the guanine nucleotide acts by relieving phospholipase C from an inhibitory constraint. Biochem. J. 271:743-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casarosa, P., R. A. Bakker, D. Verzijl, M. Narvis, H. Timmerman, R. Leurs, and M. J. Smit. 2001. Constitutive signaling of the human cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1133-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chee, M. S., A. T. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. M. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Horsnell, C. A. Hutchison, T. Kouzarides, and J. A. Martiggnetti. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, G., C. Jayawickreme, J. Way, S. Armour, K. Queen, C. Watson, D. Ignar, W. J. Chen, and T. Kenakin. 1999. Constitutive receptor systems for drug discovery. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 42:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cockcroft, S., G. M. H. Thomas, E. Cunningham, and A. Ball. 1994. Use of cytosol-depleted HL-60 cells for reconstitution studies of G-protein-regulated phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-β isozymes. Methods Enzymol. 238:154-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crump, M. P., J. H. Gong, P. Loetscher, K. Rajarathnam, A. Amara, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, J. L. Virelizier, M. Baggiolini, B. D. Sykes, and I. Clark-Lewis. 1997. Solution structure and basis for functional activity of stromal cell-derived factor-1: dissociation of CXCR4 activation from binding and inhibition of HIV-1. EMBO J. 16:6996-7007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis-Poynter, N. J., D. M. Lynch, H. Vally, G. R. Shellam, W. D. Rawlinson, B. G. Barrell, and H. E. Farrell. 1997. Identification and characterization of a G protein-coupled receptor homolog encoded by murine cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 71:1521-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Vivo, M., J. Chen, J. Codina, and R. Iyengar. 1992. Enhanced phospholipase C stimulation and transformation in NIH-3T3 cells expressing Q209LGq-α-subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 267:18263-18266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Vivo, M., and R. Iyengar. 1994. Activated Gq-α potentiates platelet-derived growth factor-stimulated mitogenesis in confluent cell cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 269:19671-19674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleckenstein, B., I. Muller, and J. Collins. 1982. Cloning of the complete human cytomegalovirus genome in cosmids. Gene 18:39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fort, P., L. Marty, M. Piechaczyk, S. el Sabrouty, C. Dani, P. Jeanteur, and J. M. Blanchard. 1985. Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase multigenic family. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:1431-1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortunato, E. A., A. K. McElroy, V. Sanchez, and D. H. Spector. 2000. Exploitation of cellular signaling and regulatory pathways by human cytomegalovirus. Trends Microbiol. 8:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraile-Ramos, A., T. N. Kledal, A. Pelchen-Matthews, K. Bowers, T. W. Schwartz, and M. Marsh. 2001. The human cytomegalovirus US28 protein is located in endocytotic vesicles and undergoes constitutive endocytosis and recycling. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:1737-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao, J. L., and P. M. Murphy. 1994. Human cytomegalovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional β-chemokine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 269:28539-28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gether, U. 2000. Uncovering molecular mechanisms involved in activation of G protein-coupled receptors. Endocr. Rev. 21:90-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gierschik, P. 1992. ADP-ribosylation of signal-transducing guanine nucleotide-binding proteins by pertussis toxin. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 175:69-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruijthuijsen, Y. K., P. Casarosa, S. J. Kaptein, J. L. Broers, R. Leurs, C. A. Bruggeman, M. J. Smit, and C. Vink. 2002. The rat cytomegalovirus R33-encoded G protein-coupled receptor signals in a constitutive fashion. J. Virol. 76:1328-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gutkind, J. S., E. A. Novotny, M. R. Brann, and K. C. Robbins. 1991. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes as agonist-dependent oncogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:4703-4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heasley, L. E., J. Zamarripa, B. Storey, B. Helfrich, F. M. Mitchell, P. A. Bunn, and G. L. Johnson. 1996. Discordant signal transduction and growth inhibition of small cell lung carcinomas induced by expression of GTPase-deficient Gα16. J. Biol. Chem. 271:349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higashita, R., L. Li, V. Van Putten, Y. Yamamura, F. Zarinetchi, L. Heasley, and R. A. Nemenoff. 1997. Gα16 mimics vasoconstrictor action to induce smooth muscle α-actin in vascular smooth muscle cells through a Jun-NH2-terminal kinase-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25845-25850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Himpens, B., P. Proot, J. Neyts, H. De Smedt, E. De Clercq, and R. Casteels. 1995. Human cytomegalovirus modulates the Ca2+ response to vasopressin and ATP in fibroblast cultures. Cell Calcium 18:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Julius, D., T. J. Livelli, T. M. Jessell, and R. Axel. 1989. Ectopic expression of the serotonin 1c receptor and the triggering of malignant transformation. Science 244:1057-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalejta, R. F., and T. Shenk. 2002. Manipulation of the cell cycle by human cytomegalovirus. Front. Biosci. 7:295-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalinec, G., A. J. Nazarali, S. Hermouet, N. Xu, and J. S. Gutkind. 1992. Mutated α-subunit of the Gq protein induces malignant transformation in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:4687-4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kempkes, B., R. Pich, B. Zeidler, B. Sugden, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1995. Immortalization of human B lymphocytes by a plasmid containing 71 kilobase pairs of Epstein-Barr virus DNA. J. Virol. 69:231-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kenakin, T., P. Morgan, M. Lutz, and J. Weiss. 2000. The evolution of drug receptor models: the cubic ternary complex model for G protein-coupled receptors, p. 147-165. In T. Kenakin and J. A. Angus (ed.), The pharmacology and functional, biochemical and recombinant receptor systems. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, vol. 148. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 44.Kledal, T. N., M. M. Rosenkilde, and T. W. Schwartz. 1998. Selective recognition of the membrane-bound CX3C chemokine, fractalkine, by the human cytomegalovirus-encoded broad-spectrum receptor US28. FEBS Lett. 441:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuhn, D. E., C. J. Beall, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1995. The cytomegalovirus US28 protein binds multiple CC chemokines with high affinity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211:325-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LaMorte, V. J., A. T. Harootunian, A. M. Spiegel, R. Y. Tsien, and J. R. Feramisco. 1993. Mediation of growth factor induced DNA synthesis and calcium mobilization by Gq and Gi2. J. Cell Biol. 121:91-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loenen, W. A., C. A. Bruggeman, and E. J. Wiertz. 2001. Immune evasion by human cytomegalovirus: lessons in immunology and cell biology. Semin. Immunol. 13:41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ling, K., P. Wang, J. Zhao, Y. L. Wu, Z. J. Cheng, G. X. Wu, W. Hu, L. Ma, and G. Pei. 1999. Five-transmembrane domains appear sufficient for a G protein-coupled receptor: functional five-transmembrane domain chemokine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7922-7927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lusso, P. 2000. Chemokines and viruses: the dearest enemies. Virology 273:228-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lustig, K. D., B. R. Conklin, P. Herzmark, R. Taussig, and H. R. Bourne. 1993. Type II adenylylcyclase integrates coincident signals from Gs, Gi, and Gq. J. Biol. Chem. 268:13900-13905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackay, C. R. 2001. Chemokines: immunology's high impact factors. Nat. Immunol. 2:95-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matuoka, K., K. Fukami, O. Nakanishi, S. Kawai, and T. Takenawa. 1988. Mitogenesis in response to PDGF and bombesin abolished by microinjection of antibody to PIP2. Science 239:640-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Messerle, M., I. Crnkovic, W. Hammerschmidt, H. Ziegler, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1997. Cloning and mutagenesis of a herpesvirus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14759-14763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michelson, S., P. Dal Monte, D. Zipeto, B. Bodaghi, L. Laurent, E. Oberlin, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, J. L. Virelizier, and M. P. Landini. 1997. Modulation of RANTES production by human cytomegalovirus infection of fibroblasts. J. Virol. 71:6495-6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moepps, B., R. Frodl, H. R. Rodewald, M. Baggiolini, and P. Gierschik. 1997. Two murine homologues of the human chemokine receptor CXCR4 mediating stromal cell-derived factor 1α activation of Gi2 are differentially expressed in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:2102-2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murdoch, C., and A. Finn. 2000. Chemokine receptors and their role in inflammation and infectious diseases. Blood 95:3032-3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murphy, P. M., M. Baggiolini, I. F. Charo, C. A. Herbert, R. Horuk, K. Matsushima, L. H. Miller, J. J. Oppenheim, and C. A. Power. 2000. International union of pharmacology. XXII. Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 52:145-176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy, P. M. 2001. Viral exploitation and subversion of the immune system through chemokine mimicry. Nat. Immunol. 2:116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neote, K., D. DiGregorio, J. Y. Mak, R. Horuk, and T. J. Schall. 1993. Molecular cloning functional expression and signaling characteristics of a CC chemokine receptor. Cell 72:415-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noh, D. Y., S. H. Shin, and S. G. Rhee. 1995. Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C and mitogenic signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1242:99-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Novotny, J., I. Rigoutsos, D. Coleman, and T. Shenk. 2001. In silico structural and functional analysis of the human cytomegalovirus (HHV5) genome. J. Mol. Biol. 310:1151-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pass, R. F. 2001. Cytomegaloviruses, p. 2675-2705. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 63.Pietruck, F., S. Busch, S. Virchow, N. Brockmeyer, and W. Siffert. 1997. Signalling properties of lysophosphatidic acid in primary human skin fibroblasts: role of pertussis toxin-sensitive GTP-binding proteins. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 355:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Posfai, G., M. D. Koop, H. A. Kirkpatrick, and F. R. Blattner. 1997. Versatile insertion plasmids for targeted manipulations in bacteria: isolation, deletion, and rescue of the pathogenicity island LEE of the Escherischia coli O157:H7 genome. J. Bacteriol. 179:4426-4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qian, N. X., M. Russell, A. M. Buhl, and G. L. Johnson. 1994. Expression of GTPase-deficient Gα16 inhibits Swiss 3T3 cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 269:17417-17423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rhee, S. G. 2001. Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:281-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rodems, S. M., and D. H. Spector. 1998. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity is sustained early during human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 72:9173-9180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosenkilde, M. M., M. Waldhoer, H. R. Lüttich, and T. W. Schwartz. 2001. Virally encoded 7TM receptors. Oncogene 20:1582-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rossi, D., and A. Zlotnik. 2000. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:217-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Samama, P., S. Cotecchia, T. Costa, and R. L. Lefkowitz. 1993. A mutation-induced activated state of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Extending the ternary complex model. J. Biol. Chem. 268:4625-4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 72.Scatchard, G. 1949. The attractions of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 51:660-672. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shibutani, T., T. M. Johnson, Z.-X. Yu, V. J. Ferrans, J. Moss, and S. E. Epstein. 1997. Pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins as mediators of the signal transduction pathways activated by cytomegalovirus infection of smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2054-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simon, M. I., M. P. Strathmann, and N. Gautam. 1991. Diversity of G proteins in signal transduction. Science 252:802-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sinzger, C., A. Grefte, B. Plachter, A. S. Gouw, T. H. The, and G. Jahn. 1995. Fibroblasts, epithelial cells, endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells are major targets of human cytomegalovirus infection in lung and gastrointestinal tissues. J. Gen. Virol. 76:741-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sinzger, C., K. Schmidt, J. Knapp, M. Kahl, R. Beck, J. Waldman, H. Hebart, H. Einsele, and G. Jahn. 1999. Modification of human cytomegalovirus tropism through propagation in vitro is associated with changes in the viral genome. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2867-2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.St. Jeor, S., T. Albrecht, F. Funk, and F. Rapp. 1974. Stimulation of cellular DNA synthesis by human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 13:353-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Streblow, D. N., C. Soderberg-Naucler, J. Vieira, P. Smith, E. Wakabayashi, F. Ruchti, K. Mattison, Y. Altschuler, and J. A. Nelson. 1999. The human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Cell 99:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thelen, M. 2001. Dancing to the tune of chemokines. Nat. Immunol. 2:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Toorkey, C. B., and D. R. Carrigan. 1989. Immunohistochemical detection of an immediate early antigen of human cytomegalovirus in normal tissues. J. Infect. Dis. 160:741-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Valyi-Nagy, T., Z. Bandi, I. Boldogh, and T. Albrecht. 1988. Hydrolysis of inositol lipids: an early signal of human cytomegalovirus infection. Arch. Virol. 101:199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vieira, J., T. J. Schall, L. Corey, and A. P. Geballe. 1998. Functional analysis of the human cytomegalovirus US28 gene by insertion mutagenesis with the green fluorescent protein gene. J. Virol. 72:8158-8165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vink, C., M. J. Smit, R. Leurs, and C. A. Bruggeman. 2001. The role of cytomegalovirus-encoded homologs of G protein-coupled receptors and chemokines in manipulation of and evasion from the immune system. J. Clin. Virol. 23:43-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wahle, E., and W. Keller. 1992. The biochemistry of 3′-end cleavage and polyadenylation of messenger RNA precursors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:419-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Waldhoer, M., T. N. Kledal, H. Farrell, and T. W. Schwartz. 2002. Murine cytomegalovirus (CMV) M33 and human CMV US28 receptors exhibit similar constitutive signaling activities. J. Virol. 76:8161-8168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Welch, A. R., L. M. McGregor, and W. Gibson. 1991. Cytomegalovirus homologs of cellular G protein-coupled receptor genes are transcribed. J. Virol. 65:3915-3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weston, K., and B. G. Barrell. 1986. Sequence of the short unique region, short repeats, and part of the long repeats of human cytomegalovirus. J. Mol. Biol. 192:177-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu, D. Q., C. H. Lee, S. G. Rhee, and M. I. Simon. 1992. Activation of phospholipase C by the α-subunits of the Gq and G11 proteins in transfected Cos-7 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 267:1811-1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Young, D., G. Waitches, C. Birchmeier, O. Fasano, and M. Wigler. 1986. Isolation and characterization of a new cellular oncogene encoding a protein with multiple potential transmembrane domains. Cell 45:711-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]