Abstract

Despite suppression of viremia in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), human immunodeficiency virus type 1 persists in a latent reservoir in the resting memory CD4+ T lymphocytes and possibly in other reservoirs. To better understand the mechanisms of viral persistence, we established a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-macaque model to mimic the clinical situation of patients on suppressive HAART and developed assays to detect latently infected cells in the SIV-macaque system. In this model, treatment of SIV-infected pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) with the combination of 9-R-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl)adenine (PMPA; tenofovir) and beta-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thia-5-fluorocytidine (FTC) suppressed the levels of plasma virus to below the limit of detection (100 copies of viral RNA per ml). In treated animals, levels of viremia remained close to or below the limit of detection for up to 6 months except for an isolated “blip” of detectable viremia in each animal. Latent virus was measured in blood, spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus by several different methods. Replication-competent virus was recovered after activation of a 99.5% pure population of resting CD4+ T lymphocytes from a lymph node of a treated animal. Integrated SIV DNA was detected in resting CD4+ T cells from spleen, peripheral blood, and various lymph nodes including those draining the gut, the head, and the limbs. In contrast to the wide distribution of latently infected cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues, neither replication-competent virus nor integrated SIV DNA was detected in thymocytes, suggesting that thymocytes are not a major reservoir for virus in pig-tailed macaques. The results provide the first evidence for a latent viral reservoir for SIV in macaques and the most extensive survey of the distribution of latently infected cells in the host.

Advances in antiretroviral therapy, particularly the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), allow control of viral replication in patients with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. HAART regimens consist of combinations of antiretroviral drugs that together successfully reduce plasma HIV-1 RNA levels in the majority of patients to below the limit of detection of current assays (20, 21, 38). However, HIV-1 persists even in successfully treated patients whose plasma virus levels have fallen to undetectable levels (12, 16, 52). The viral reservoir for which long-term persistence has been most clearly demonstrated consists of latently infected resting CD4+ T lymphocytes (10-12, 15, 16, 38, 39, 52). These have stably integrated provirus (10-12), but show no virus production until they are activated (10). These latently infected CD4+ T lymphocytes have been found in the peripheral blood (10, 11, 16) and lymph nodes (11) of infected individuals, but little is known about the presence of these cells in other lymphoid organs, such as the spleen or thymus. Reservoirs have also been postulated to exist in other cell types, such as monocytes/macrophages, and in anatomical sites such as the central nervous system (6).

Latently infected resting CD4+ T cells generally have a memory phenotype (11, 41). In light of the fact that direct productive infection of resting CD4+ T cells is difficult to demonstrate (9, 42, 54), it has been proposed that these cells may arise when productively infected, activated CD4+ T cells revert back to a resting memory state (10). However, recent studies with a SCID/hu mouse system have suggested that latently infected cells can also be generated in the thymus (8). Although the extent of thymic infection is difficult to measure because of the inaccessibility of the organ, it is well accepted that infection of thymocytes can occur during human and primate retroviral infections (2, 30, 32, 35, 45, 47, 53; reviewed in references 19 and 23). In the SCID/hu Thy/Liv model of HIV-1 infection, direct infection and depletion of thymocytes in the implanted fetal-thymus graft can be demonstrated (7). In addition, there is substantial evidence of decreased thymic function during HIV-1 infection (13, 44). During disease progression, the thymic architecture is disturbed and there is virus-related depletion of the thymocytes (49).

To study the viral reservoirs that allow persistence in the face of potent antiretroviral therapy, we developed a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-macaque model that would enable us to examine different potential viral reservoirs that are not easily accessible in humans. SIV-macaque models of AIDS are well established and have been extremely useful in HIV-1 vaccine development and in advancing the understanding of the pathogenesis of AIDS (reviewed in references 25 and 31). However, they have not been widely utilized as a model for the study of HIV-1 infection under HAART because of the lack of SIV protease inhibitors, nor have they been used for the study of latent viral reservoirs. Recently, several groups have developed combinations of reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors that can successfully suppress viremia in infected macaques to levels below the detection limit (33; D. D. Richman, personal communication). We therefore treated SIV-infected pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) with two potent RT inhibitors for 6 months and measured the persistence of latent SIV in various lymphoid compartments by using a series of novel assays. The results provided insight into the nature of viral persistence in the setting of HAART.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

SIV/17E-Fr (17, 34) is a macrophage-tropic and neurovirulent recombinant strain derived from SIVmac239 by replacement of the entire env and nef genes as well as the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) of SIVmac239 with those from SIV/17E-Br, a virus derived from SIVmac239 by serial passage in rhesus macaques and subsequent isolation from the brain of a macaque with fulminant encephalitis (48).

Animal experiments.

Four juvenile pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina), aged 3 to 4 years, were inoculated intravenously with SIV/17E-Fr (10,000 50% tissue culture infective doses). Beginning on day 50 postinoculation (p.i.), two of the animals (98P004 and 98P008) were injected once daily subcutaneously with the antiretroviral drugs 9-R-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl)adenine (PMPA; tenofovir) and beta-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thia-5-fluorocytidine (FTC) at doses of 20 and 50 mg/kg of body weight/day, respectively. Then, beginning on day 85 p.i., the dose for PMPA was increased to 30 mg/kg/day for the rest of the study. The other two animals (98P009 and 97P021) were not given any drugs and served as no-therapy controls. PMPA is a nucleotide RT inhibitor that does not cross the brain-blood barrier (1, 18), and FTC is a nucleoside RT inhibitor that crosses the blood-brain barrier (46).

Blood was drawn from each animal for plasma viral-load assays weekly until day 77 p.i. and biweekly thereafter. Axillary lymph nodes were taken from the animals at week 3 (98P004 and 98P008), week 4 (98P009 and 97P021), week 13 (all), and week 23 (all) to be examined for the presence of virus. All manipulations were done while the animals were anesthetized with ketamine-HCl (Parke-Davis). The animals were euthanatized at 29 to 33 weeks p.i. Prior to necropsy, animals were perfused with sterile phosphate-buffered saline to remove virus-containing blood from the tissues. Latently infected resting T cells were quantified in six different tissues: thymus, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, pooled retropharyngeal and cervical lymph nodes, and pooled axillary and inguinal lymph nodes. The following lymphoid tissues were examined microscopically for abnormalities: spleen, thymus, intestinal lymph nodes (mesenteric and colonic), peripheral lymph nodes (axillary and inguinal), and lymph nodes of the head (cervical, submandibular, and retropharyngeal).

Histopathology.

Spleen, thymus, peripheral (axillary and inguinal) nodes, intestinal (mesenteric and colonic) nodes, and nodes that drain the head (submandibular, retropharyngeal, and cervical) were sampled at necropsy. The tissues were fixed in Streck's tissue fixative (Streck Laboratories, La Vista, Nebr.) for 7 days, and then sectioned and routinely processed and paraffin embedded. A 5-μm section from spleen and each lymph node was stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined microscopically. Changes in lymphoid tissues included follicular hyperplasia, paracortical expansion, lymphoid depletion, and medullary fibrosis. The severity of these pathological changes was subjectively scored as mild, moderate, or severe.

Plasma viral load.

Virion-associated SIV RNA in plasma was measured by using a real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay on an Applied Biosystems Prism 7700 sequence detection system (the Taqman method), as previously described (24, 50). For each sample, three reactions were performed. Duplicate aliquots were separately reverse transcribed and amplified, and the amplification cycle during which a detectable PCR product was first observed (threshold cycle) was determined from real-time kinetic analysis of fluorescent-product generation as a consequence of template-specific amplification (50). To control for DNA contamination, one reaction was processed and amplified without addition of RT (no RT control). Nominal copy numbers for test samples were then automatically calculated by interpolation of the experimentally determined threshold cycle values onto a regression curve derived from control transcript standards, followed by normalization for the volume of the extracted plasma specimen.

Isolation of resting CD4+ T cells.

Various tissues, including the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, pooled retropharyngeal and cervical lymph nodes, and pooled axillary and inguinal lymph nodes, were teased apart with needles to form single-cell suspensions. The monocytes were depleted by adherence (incubation at 37°C overnight). Nonadherent cells were labeled with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-HLA-DR antibodies (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems) and sorted on a MoFlo (Cytomation) cell sorter for small CD4+/HLA-DR− cells. Thus, activated T cells were removed on the basis of size and expression of HLA-DR.

Isolation of CD4+/CD8− and CD4+/CD8+ T cells from the thymus.

Thymus tissue was processed to obtain a single-cell suspension as described for other tissues. Then, thymocytes were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 and PE-conjugated anti-CD4 antibodies (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems) and sorted on a MoFlo cell sorter for CD4+/CD8− single-positive and CD4+/CD8+ double-positive cells.

Quantification of latently infected cells.

Latently infected cells were quantified by using a novel limiting dilution culture assay in which highly purified resting CD4+ T cells were cocultured with CEMx174 cells (a gift from James Hoxie, University of Pennsylvania) in duplicate fivefold serial dilutions ranging from as many as 5 × 106 cells per well to as few as 320 cells per well. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 4 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin (50 U/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), and interleukin-2 (100 U/ml). For cultures containing 0.2 × 106 to 10 × 106 primary cells/well, the ratio of primary cells to CEMx174 cells was 4:1, and for cultures containing 320 to 200,000 primary cells, a constant number of 50,000 CEMx174 cells were used. The cultures were split 1:2 every 2 days, and fresh medium was added. After 21 days, growth of virus was detected by measuring p27 antigen in culture supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Beckman Coulter). Control wells with only primary cells or only CEMx174 cells were included in each assay. The frequencies of infected cells were determined by the maximum-likelihood method (36) and were expressed in terms of infectious units per million (IUPM) resting CD4+ T cells.

Assay for integrated SIV DNA.

Integrated SIV DNA was detected by using a modified version of a previously described inverse-PCR method (10). Genomic DNA (800 ng) extracted from primary cells by using the Puregene genomic DNA isolation kit (Gentra) was digested with 10 U of BsrG1 (New England Biolabs) for 3 h at 37°C and then incubated with an additional 10 U of BsrG1 for 3 h at 60°C. After heat inactivation for 20 min at 80°C, 600 ng of DNA was ligated with 5 U of T4 DNA ligase (Boehringer Mannheim) in a 60-μl total volume of 66 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM ATP for 12 h at 16°C. A portion of the digested DNA (200 ng) was incubated in a similar manner but without ligase. Tubes were then heat inactivated at 65°C for 15 min to inactivate ligase.

Approximately 200 ng of genomic DNA was used in each PCR mixture containing 1 μM concentrations of each primer, 200 μM concentrations of deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 3.5 U of the Expand Long Template PCR polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). The primers for the first PCR were as follows: 5′ primer, 5′AGACCAACAGCACCATCTAGCGGCAGAG3′, and 3′ primer, 5′TCCCTGACAAGACGGAGTTTCTCACGC3′. The primers for the second (nested) PCR were as follows: 5′ primer, 5′GAGCCGTCAGGATCAGATATTGCAGGAACAAC, and 3′ primer, 5′GCCCTTACTGCCTTCACTCAGCCGTACTC3′. The 3′ primers were at the 5′ end of the gag gene, and the 5′ primers were just 5′ of the BsrG1 restriction site in gag. The first PCR was initiated by heating at 95°C for 12 min, followed by cycling between 94°C (for 30 s) and 68°C (for 4 min) for 35 cycles. The first PCR was done in a 50-μl volume, and 1 μl of the product was used as the template in the nested PCR. The nested PCR was cycled between 94°C (for 30 s) and 68°C (for 4 min) for 25 cycles after initial heating at 95°C for 3 min. Products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The desired fragments (size greater than 900 bp) were gel purified (Qiagen) and cloned with a Zero Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen). Positive clones were sequenced by using standard cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). A BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information) search of the human genome was done to identify the location of the genomic sequences contained in the clones.

A plasmid standard was generated to measure the sensitivity of inverse PCR. The plasmid FrB/B was constructed by removing a BamHI/BlpI fragment between the middle of gag and the end of the 3′ LTR region from a plasmid containing the SIV/17E-Fr provirus. This deleted plasmid was used in a 10-fold serial dilution (into 200 ng of genomic DNA) as a control for the first and nested inverse PCRs.

Quantification of total SIV DNA.

The total number of copies of SIV DNA (including integrated and unintegrated species) was determined by using a quantitative real-time PCR method similar to that used in the viral-load assay except for the omission of the reverse transcription step. Two hundred nanograms of genomic DNA was used in each reaction, and each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Flow cytometric analysis of thymocytes.

Thymocytes were labeled with peridinin chlorophyll protein-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems), FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 antibody (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems), and PE-conjugated antibodies to CXCR4 (clone 12G5; Pharmingen) or CCR5 (clone 3A9; Pharmingen) for examination of the expression of the SIV and HIV-1 coreceptors on various subpopulations (the CD4/CD8 double positives and the CD4 and CD8 single positives). The cells were analyzed on a three-color FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

RESULTS

Suppression of SIV viremia by RT inhibitors.

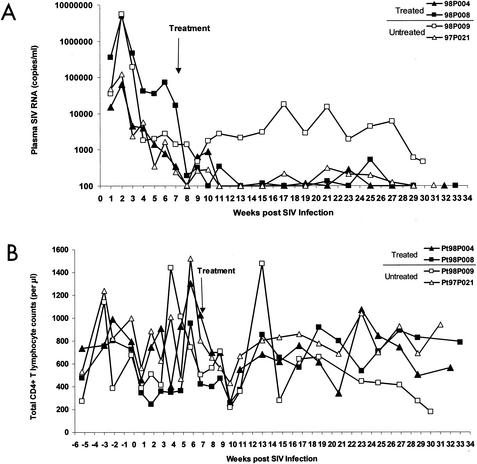

Four pig-tailed macaques were inoculated intravenously with SIV/17E-Fr, a neurovirulent SIV isolate derived from SIVmac239. All four animals developed primary viremia at 2 weeks p.i., with plasma SIV RNA levels in two animals, 98P008 and 98P009, approaching 107 copies/ml and those in two others, 98P004 and 97P021, approaching 105 copies/ml (Fig. 1A). Beginning on day 50 p.i., when the levels of viremia had declined substantially from acute-infection peaks (to approximately 105 copies/ml in animal 98P008 and 103 copies/ml in the other three macaques), two of the animals, 98P004 (low peak viremia) and 98P008 (high peak viremia), were started on a combination of two potent RT inhibitors, PMPA and FTC. The other two animals, 98P009 (high peak viremia) and 97P021 (low peak viremia), were not given any drugs and served as no-therapy controls. Because levels of viremia were still declining at the time therapy was initiated, subsequent decreases in viremia could in principle be due to immunologic mechanisms, therapy, or both. However, several lines of evidence suggest that the RT inhibitors contributed to the suppression of viremia. First, in animal 98P008, the slope of the decline in viremia became abruptly sharper coincident with the initiation of therapy. Second, this animal achieved suppression of viremia despite a high peak viremia (107 copies/ml). The untreated control animal that had a similarly high peak viremia never achieved suppression of viremia to below the limit of detection (100 copies/ml) and remained viremic (103 to 104 copies/ml) throughout the study. Third, more consistent suppression of viremia over the long term was observed in the treated animals than in the untreated controls. One untreated control animal, 97P021, had a low peak viremia and then naturally controlled viral replication to below 100 copies/ml. However, after week 13 there were four episodes of viremia in the range of 150 to 300 copies/ml. Both treated animals had suppression of viremia to close to or below the limit of detection by week 13 and only a single “blip” of detectable viremia over 150 copies/ml for the remainder of the study. Thus, although the two-drug regimen used here is not likely to be as potent as the typical three- or four-drug regimens used in humans, this system did allow suppression of viremia to levels roughly comparable to those observed in HIV-1-infected humans on HAART. An additional similarity is the occurrence of isolated blips. In patients on HAART, blips are common and do not predict impending treatment failure (22). The blips observed in the treated animals in our study were followed by decreases in viremia to below the limit of detection. We therefore conclude that this model provides a reasonable first approximation for HAART in humans.

FIG. 1.

Viral loads and CD4 counts in SIV-infected pig-tailed macaques on antiretroviral therapy. (A) Suppression of plasma virus levels in PMPA- and FTC-treated pig-tailed macaques. All animals were infected intravenously with 10,000 50% tissue culture infective doses of SIV/17E-Fr, and animals 98P004 (▴) and 98P008 (▪) were treated with PMPA and FTC starting at day 50 p.i. Animals 98P009 (□) and 97P021 (▵) were not treated. Plasma viral load, in SIV RNA copies per milliliter of plasma, was measured with a quantitative reverse transcription-PCR method (sensitivity, 100 copies/ml). The arrow indicates when the treatment began. (B) CD4 counts in treated and untreated animals.

CD4 counts fluctuated over time in each animal (Fig. 1B), as is typical in pig-tailed macaques. At later time points, significant CD4 depletion was evident in the untreated control animal, 98P009, that remained viremic throughout the study.

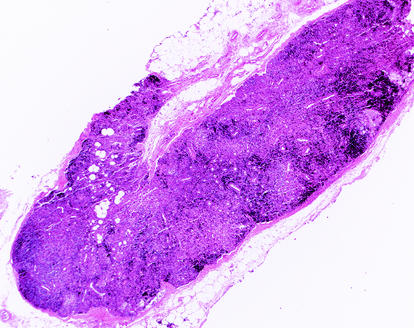

Pathological changes in lymphoid tissues.

At the time of necropsy, macaques had either mild (98P004 and 97P021) or moderate (98P008 and 98P009) depletion of lymphoid follicles in the spleen. The thymus was normal in two macaques (98P009 and 97P021) and was mildly or moderately atrophic in the remaining two macaques (98P008 and 98P004, respectively). In all animals, there was moderate lymphoid atrophy of the intestinal (mesenteric and colonic), peripheral (axillary and inguinal), and head-draining (cervical, submandibular, and retropharyngeal) lymph nodes. Lymphoid atrophy of the spleen and lymph nodes was most prominent in a treated macaque, 98P008, which had high peak viremia before starting HAART (Fig. 2). This suggests that the mechanisms that lead to lymphoid depletion were operating in this animal prior to the initiation of therapy. Taken together, these results suggest that infection with SIV/17E-Fr initiates a process of lymphoid depletion that is very similar to that seen in HIV-1 infection.

FIG. 2.

Histologic evidence for CD4 depletion. At the time of necropsy, the inguinal lymph node of macaque 98P008 demonstrated severe lymphoid atrophy with depletion of both cortical lymphoid follicles and lymphocytes from the paracortical zone. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification, ×20.

Detection of replication-competent virus in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes in various compartments by use of a virus culture assay.

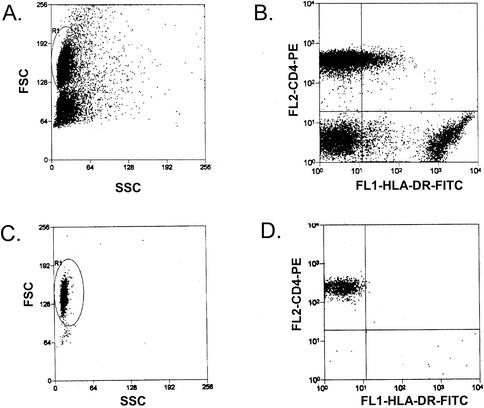

A stable reservoir for HIV-1 exists in latently infected resting CD4+ T cells (see references cited in the Introduction). To determine whether such a reservoir is present in SIV infection, resting CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated from mononuclear-cell preparations from peripheral blood, lymph nodes, and spleen. Resting cells were isolated by sorting for small CD4+/HLA-DR− cells. Prior to sorting, a substantial portion of the CD4+ T cells expressed HLA-DR, indicative of an activated state. As is shown in Fig. 3, sorting yielded a population of uniformly small CD4+/HLA-DR− cells. The purity of the sorted cell populations was at least 98.3%, with less that 0.5% contamination with activated cells. As is the case with highly purified resting CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-infected humans, purified resting CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected macaques did not produce virus without cellular activation. To induce activation, purified resting CD4+ T cells were cocultured with a human hybrid T-B-lymphocyte cell line, CEMx174, that serves both to induce contact-dependent activation of resting macaque T cells and to amplify virus released from latently infected primary cells (A. Shen et al., unpublished data). Coculturing with CEMx174 cells was sufficient to activate the resting cells as well as to rescue single-copy infectious virus from them (Shen et al., unpublished). Positive wells were identified by SIV p27 assays of the supernatant at the end of 21 days in culture. Control wells with only CEMx174 cells or sorted resting CD4+ T cells from infected animals were included in each assay and were invariably negative for p27. In some experiments, sorted resting CD4+ T cells were cultured with CEMx174 in transwells to control for release of virus without activation of resting cells. The p27 assay results for these controls were always negative. Infected-cell frequencies were determined by the maximum-likelihood method and were expressed in terms of IUPM resting CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 3.

Purification of resting CD4+ T cells from infected macaques. Representative forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) profiles (A and C) and CD4 versus HLA-DR staining (B and D) are shown before purification (A and B) and after purification by cell sorting (C and D). The purified resting CD4+-T-cell populations (CD4+/HLA-DR−) typically showed <0.5% contamination with activated cells (CD4+/HLA-DR+).

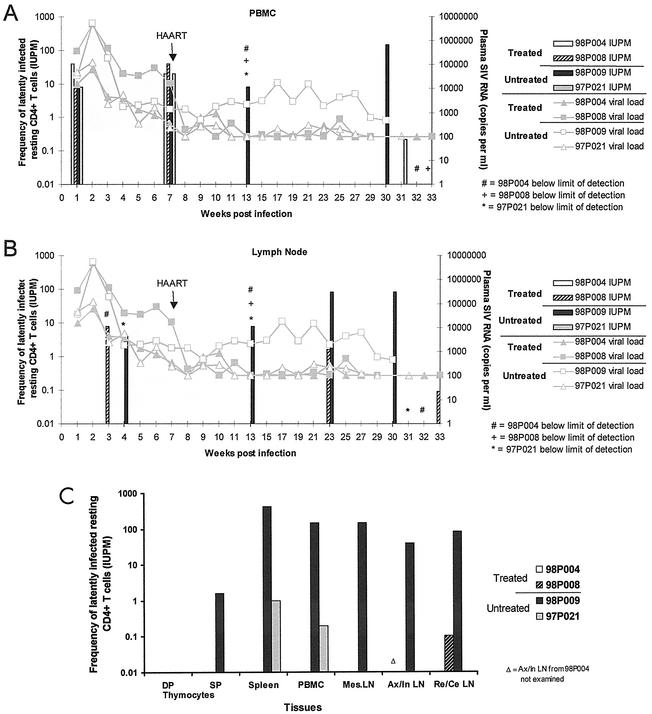

Before the initiation of treatment with PMPA and FTC, replication-competent virus was isolated from purified resting CD4+ T lymphocytes from peripheral blood of all animals (Fig. 4A). After the initiation of treatment, however, virus could no longer be recovered from resting CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood of treated animals, while cultures from untreated animals remained positive. At the last time point (necropsy), as many as 5 × 106 purified resting CD4+ T cells were cultured and cultures from treated animals were still negative, suggesting that the frequency of latently infected cells was <1 per 5 × 106 resting CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 4.

Detection of replication-competent virus in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes in various compartments by virus culture assay. Purified CD4+/HLA-DR− T lymphocytes from SIV-infected macaques were cultured in fivefold limiting dilutions with CEMx174 cells to measure the frequency of cells harboring replication-competent virus. The results are expressed in terms of IUPM resting CD4+ T lymphocytes. (A) Resting CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood were examined at weeks 1, 7, and 13 p.i. and at necropsy (weeks 30, 31, 32, and 33 p.i. for animals 98P009, 97P021, 98P004, and 98P008, respectively; same for results shown in panel C). Lines show the plasma viral load at various time points (limit of detection, 100 copies/ml), and the bars show the IUPM values. (B) Lymph nodes were examined at weeks 3 and 4, 13, and 23 p.i. and at necropsy. (C) At necropsy, the frequencies of resting CD4+ T lymphocytes harboring replication-competent virus in spleen, peripheral blood, and mesenteric (Mes), axillary (Ax), inguinal (In), cervical (Ce), and retropharyngeal (Re) lymph nodes (LN) were determined. Axillary and inguinal lymph nodes (draining the arms and legs, respectively) were pooled. Cervical and retropharyngeal lymph nodes (draining different regions of the head and neck) were also pooled. CD4 single-positive (SP) and CD4/CD8 double-positive (DP) cells from the thymus were also examined. All tissues were examined from all four animals except for pooled axillary and inguinal lymph nodes from 98P004 due to insufficient numbers available (Δ).

In the lymph nodes, virus was detected in the resting CD4+ T cells from the two animals with higher peak viremia (98P008 and 98P009) and not in the ones with lower peak viremia (98P004 and 97P021) throughout the course of study (Fig. 4B). After the initiation of treatment, there was a decrease in the frequency of detectable virus in treated animal 98P008 (similar to that observed in humans [4]). However, despite suppression of plasma viral RNA to undetectable levels for 5 months, replication-competent virus was still recovered from 98P008 at a frequency of 1.6 IUPM at the last time point at 33 weeks p.i.

At necropsy, resting CD4+ T lymphocytes were purified and cultured from various tissues including peripheral blood, spleen, and mesenteric, axillary, inguinal, cervical, and retropharyngeal lymph nodes (Fig. 4C). In this analysis, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes (draining the arms and legs, respectively) were pooled. Cervical and retropharyngeal lymph nodes (draining different regions of the head and neck) were also pooled. For the untreated viremic animal (98P009), virus was cultured from resting CD4+ T lymphocytes from all tissues. The highest frequencies were found in the spleen (420 IUPM), followed by the peripheral blood (143 IUPM), with somewhat lower frequencies in the lymph nodes (40 to 143 IUPM). CD4 single-positive and CD4/CD8 double-positive thymocytes were also studied in this culture system and were found to have extremely low levels of virus. No virus was detected in double-positive cells, and in single-positive cells from animal 98P009, the frequency was only 1.6 IUPM, almost 2 logs lower than that observed in resting CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood. In the untreated animal that naturally controlled virus (97P021), most virus was detected in resting CD4+ T cells from the spleen (1.6 IUPM), followed by the peripheral blood (0.2 IUPM). Virus levels in all of the other tissues were below the limit of detection.

Previous studies of HIV-1-infected humans have shown that latent virus in resting CD4+ T cells exists in two forms, a labile preintegration form that declines in the first 3 months of treatment and a stable integrated form that persists for years despite suppressive antiretroviral therapy. In untreated animals, virus cultured from resting CD4+ T cells could in principle be derived from infected resting cells in either pre- or postintegration latency (4, 11). Because the preintegration forms of the virus are labile and decay rapidly when new infection is arrested by HAART (4, 42), virus culture assays in the setting of long-term viral suppression with HAART reveal the postintegration form of latency. In the treated animal with higher peak viremia (98P008), virus was detected from pooled cervical and retropharyngeal lymph nodes, despite the fact that plasma virus had been undetectable in this animal for more than 5 months (Fig. 4C). The frequency of latently infected cells was approximately 0.1 per 106 cells. No virus was detected in the resting CD4+ T cells from the other treated animal with lower peak viremia (98P004) in any compartment, suggesting that the frequencies of latently infected cells with replication-competent virus were below the limit of detection with the number of input cells available (<0.1 to 1 per 106 cells).

Taken together, these results suggest that latent SIV can be recovered from resting CD4+ T cells from various lymphoid tissues of viremic animals, including spleen, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood. In sharp contrast, thymocytes showed a rate of infection that was orders of magnitude less than that of mature peripheral CD4+ T cells. Most importantly, following suppression of viremia to below the detection limit with HAART for more than 5 months, replication-competent virus still could be recovered after activation of purified resting CD4+ T cells from the lymph node, providing direct evidence for the existence of a stable viral reservoir for SIV in resting CD4+ T cells.

Detection of integrated SIV DNA in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes by inverse PCR.

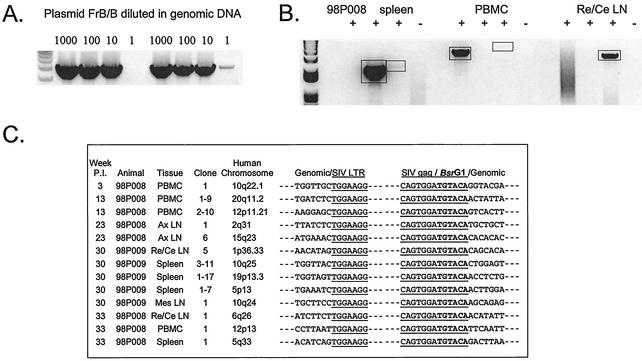

To provide definitive evidence for a stable reservoir of integrated SIV in resting CD4+ T cells, high-molecular-weight DNA was isolated from the purified resting CD4+ T lymphocytes and subjected to inverse PCR to detect SIV DNA integrated in host cell DNA. Using a plasmid standard serially diluted into 200 ng of genomic DNA, this inverse PCR was shown to be capable of detecting a single-copy viral DNA (Fig. 5A [results of two independent PCRs are shown]).

FIG. 5.

Detection of integrated SIV DNA in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes by inverse PCR. (A) Sensitivity of inverse PCR. The plasmid FrB/B was constructed by excising a BamHI/BlpI fragment between the middle of the gag gene and the end of 3′ LTR region from a plasmid containing the SIV/17E-Fr provirus. Inverse PCR amplification of this template gives a 4.5-kb product. This plasmid was serially diluted into 200 ng of genomic DNA as a control for the initial and nested PCRs. Results of two independent PCRs are shown. (B) Representative inverse PCRs from different tissues from treated animal 98P008. Lanes indicate the addition (+) and omission (−) of ligase in the ligation reaction, respectively. Bands were cloned and sequenced. Re/Ce LN, retropharyngeal and cervical lymph nodes. (C) Inverse PCR allows definitive identification of integration sites. Integration sites are shown as sequences immediately upstream of the LTR. Note that the LTR shows the characteristic loss of the terminal two nucleotides (5′AC) resulting from the cleavage by integrase of the two terminal bases from the 3′ end of each strand of the full-length linear SIV genome. The other junction results from ligation of cut BsrG1 sites in gag and in macaque DNA upstream of the integration site. The macaque sequences cloned by this method are each homologous (>90%) to the indicated sequences in the human genome. Ax LN, axillary lymph nodes; Mes LN, mesenteric lymph nodes.

Integrated SIV DNA was detected in resting CD4+ T cells from treated animal 98P008 at many time points (Fig. 5B and C). Even after 6 months on treatment, with suppression of viremia to below the detection limit, integrated SIV DNA could still be detected in resting CD4+ T cells from spleen, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood from this animal (Fig. 5B and C). Integrated SIV DNA was also detected in resting CD4+ T cells from the untreated viremic animal (98P009) at the end of the study (Fig. 5C) but was not detected in the other two animals (98P004 and 97P021). Integration sites in the macaque genome were identified by using the human genome database, and each showed >90% homology with a different sequence in the human genome. The 5′ LTR of the integrated SIV proviruses showed the characteristic loss of the terminal two nucleotides (5′AC) resulting from the cleavage by integrase during the integration reaction (Fig. 5C, column labeled “Genomic/SIV LTR”). These results demonstrate definitively that integrated SIV DNA persists in highly purified resting CD4+ T cells of macaques on combination therapy despite the absence of measurable plasma virus. In contrast, no integrated SIV DNA was found in thymocytes from any animal.

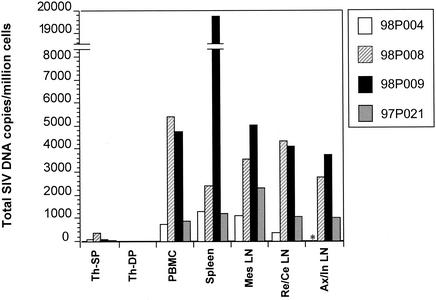

Quantification of SIV DNA in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes in various tissues and thymocytes.

Although inverse PCR allows definitive identification of integration sites, it was difficult to obtain a quantitative assessment. Therefore, real-time PCR was performed to quantify SIV DNA in purified resting CD4+ T cells from tissues examined at necropsy (Fig. 6). Although the real-time PCR used in this study did not distinguish integrated from unintegrated SIV DNA, it provided information on the total level of infection in those tissues. Moreover, in the aviremic animals, in the absence of ongoing replication, the unintegrated DNA pool should have decayed, leaving predominantly the integrated virus. The results showed that while SIV DNA was readily detected in resting CD4+ T cells from all peripheral lymphoid tissues (blood, spleen, and lymph nodes), the levels of SIV DNA in thymocytes were extremely low (Fig. 6). SIV DNA was not detected in CD4/CD8 double-positive cells from the thymus, and only a very small amount was detected in the CD4 single-positive cells from the thymus. In the animal that was viremic at the time of necropsy (98P009), the spleen had by far the most viral DNA, consistent with the results from the culture studies. In all of the aviremic animals, the amounts of viral DNA in resting CD4+ T cells from blood, spleen, and various lymph nodes were similar. Viral DNA levels in tissues did not correlate with plasma viral load (Fig. 1A and 6). Animal 98P008 had the same low level of plasma virus as did animals 98P004 and 97P021 at the time of sampling but had a higher level of viral DNA in all tissues examined except for the thymus. However, viral DNA levels in tissues did correlate with the level of peak viremia (Fig. 1A and 6). Animals 98P008 and 98P009 had higher viral loads at peak viremia than did animals 98P004 and 97P021 (Fig. 1A), and they also had higher amounts of viral DNA in the tissues (Fig. 6). The ready detection of SIV DNA in the peripheral lymphoid organs of all animals suggests that real-time PCR detects both replication-competent and defective forms of the virus in resting CD4+ T cells while the culture assay can detect only the former. The real-time PCR does provide a quantitative assessment of the level of infection of various organs and confirms the relative sparing of the thymus as a site of viral replication in vivo in this system.

FIG. 6.

Quantification of total SIV DNA in various tissues from all four macaques by quantitative real-time PCR at necropsy. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with DNA from purified cells from different tissues. Animals 98P004 and 98P008 were treated, but animals 98P009 and 97P021 were not treated. Various tissues were examined, including CD4+ single-positive (SP) cells and CD4/CD8 double-positive (DP) cells from the thymus (Th) and purified resting CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood, mesenteric lymph nodes (Mes LN), pooled retropharyngeal and cervical lymph nodes (Re/Ce LN), and pooled axillary and inguinal lymph nodes (Ax/In LN). The asterisk indicates that Ax/In LN were not available for animal 98P004.

Several additional studies were performed to provide insight into the low level of thymic infection observed. To ensure that the low level of infection observed in the single-positive and double-positive thymocyte populations by culture assay and by PCR was not due to exclusion of infected cells that had downregulated CD4, unfractionated thymocytes were also analyzed. As many as 107 thymocytes were cultured from animal 98P009, which had the highest plasma viral level, and no p27 production was detected. DNA from unfractionated thymocytes was tested with quantitative real-time PCR and was found to have levels of SIV DNA that were similar to or lower than those in the single-positive cells. To determine whether animals with end stage disease would show a higher degree of thymic infection, a terminally ill pig-tailed macaque from another study was examined by using the culture assay. Even though high levels (40 IUPM) of replication-competent virus could be recovered from resting CD4+ T cells from the peripheral blood, the level of infection of unfractionated thymocytes was substantially lower (1 IUPM).

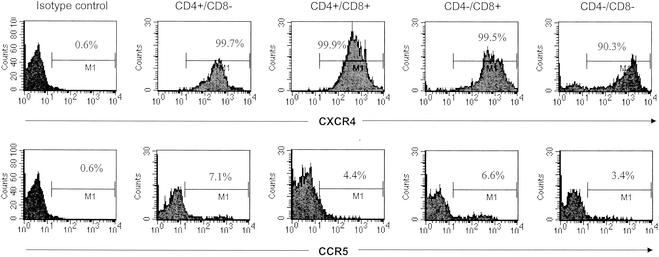

Expression of CCR5 and CXCR4 on macaque thymocytes.

To provide further insight into the apparent lack of infection of thymocytes in vivo, we examined the expression of the SIV and HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 as well as the HIV-1 coreceptor CXCR4 on different populations of thymocytes (a representative result is shown in Fig. 7). CXCR4, a coreceptor for HIV-1 but not for SIV, was expressed on almost all macaque thymocytes (>90% in four subpopulations [Fig. 7, top panels]); CCR5, the main coreceptor for all SIV strains, was expressed by only a very low percentage of the thymocytes (<10% in all subpopulations [Fig. 7, bottom panels]).

FIG. 7.

Expression of SIV and HIV-1 coreceptor CCR5 (bottom panels) and HIV-1 coreceptor CXCR4 (top panels) on the thymocytes. Data for the CD4+ single-positive cells, the CD4/CD8 double-positive cells, the CD8+ single-positive cells, and the CD4/CD8 double-negative cells are indicated with the appropriate labels above the panels. The double-negative subpopulation might include cells other than thymocytes. Percentages of expression are also indicated within the panels. The thymocytes were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 antibody and peridinin chlorophyll protein-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody to obtain the gated subpopulations and were labeled with PE-conjugated antibodies to CXCR4 or CCR5.

DISCUSSION

We have developed an animal model mimicking the situation of HIV-1-infected patients on HAART. The model involves treatment of SIV-infected macaques with potent new RT inhibitors. In this model, we demonstrated that an SIV reservoir exists in resting CD4+ T lymphocytes, both in the antiretroviral-treated and untreated animals. To our knowledge, this is the first direct demonstration of such a viral reservoir in the SIV-macaque system. We used this model to examine the persistence of virus in the blood and various lymphoid tissues. SIV DNA was readily detected in resting CD4+ T cells in tissues that harbor mature T cells, including blood, spleen, and various lymph nodes. At least a portion of this SIV DNA was integrated into the genome of host T cells as demonstrated by inverse PCR. The spleen and the lymph nodes were found to be significant reservoir sites for latently infected resting T cells along with peripheral blood. This is the first direct evidence for latently infected cells in the spleen. Given the large size of this organ, these results suggest that the spleen may harbor a substantial collection of latently infected cells. Replication-competent virus could be recovered from latently infected resting CD4+ T cells despite prolonged suppression of viremia to levels below the limit of detection. In contrast, infection in the thymocytes was extremely rare, indicating that thymocytes are not a major viral reservoir in this model. This model, if confirmed, may be useful in providing a more complete picture of viral persistence in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy and in the preclinical evaluation of novel strategies for eradicating this reservoir, such as the use of interleukin-2 and prostratin (28, 29; T.-W. Chun, D. Engel, S. Mizell, J. Metcalf, J. Hallahan, J. Kovacs, R. Davey, M. Dybul, J. Mican, C. Lane, and A. Fauci, Abstr. 6th Conf. Retrovir. and Opportunistic Infections, abstr. 496, 1999).

In humans infected with HIV-1, treatment with individual antiretroviral drugs or with two-drug combinations rarely suppresses viremia for more than several months. The fact that the animals studied here maintained suppression on two RT inhibitors for 6 months may reflect the potency of these new drugs or the fact that replication of the neurovirulent SIV clone used in this study was more easily controlled than replication of typical HIV-1 isolates. Nevertheless, pathological examination of lymphoid tissues revealed evidence of lymphoid depletion, indicating that this virus can produce immunodeficiency similar to that seen in HIV-1-infected humans. After the initiation of drug treatment, plasma virus levels in the treated animals dropped dramatically in the first week, particularly in animal 98P008. Thereafter, we observed a slower decay, similar to the second phase of decay of plasma virus observed in HIV-1-infected individuals after the initiation of HAART (38). One of the two untreated animals naturally controlled viral replication and therefore resembles those rare humans with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. The other untreated animal remained viremic throughout the study. Interestingly, even though replication of the SIV clone used here was relatively easily controlled, we were nevertheless able to demonstrate viral persistence in resting CD4+ T cells. The two treated animals occasionally had detectable virus in the plasma and therefore resemble many patients on HAART who have occasional virus blips (43). Taken together, these results suggest that this SIV-macaque model duplicates many aspects of what occurs with human patients on HAART.

From both the treated and untreated animals, replication-competent virus was recovered by activating the resting CD4+ T lymphocytes in culture, indicating that a reservoir persists in spite of drug treatment and suppression of viremia. Without T-cell activation, no virus was recovered from resting CD4+ T cells, indicating a state of latent infection. In the same resting cells, integrated SIV DNA was detected by using an assay that definitively identifies integration sites. These results suggest that postintegration latency existed in these cells. Based on studies in humans with HIV-1 infection, these latent resting cells were determined to be memory T cells (instead of naïve cells), which were most likely infected during a state of cell activation, allowing the cells to become permissive for viral integration (11). Subsequently, the activated cells return to a resting state, in which expression of viral genes is limited probably by the lack of critical host transcription factors (14, 37) or epigenetic mechanisms (27). The notion that resting T cells harboring integrated latent virus are derived from infected activated T cells is based on the observation that direct infection of resting T cells in humans is blocked prior to integration and does not result in viral gene expression (40). Direct in vitro infection of macaque resting T cells with SIV/17E-Fr in this study was also found to be similarly nonproductive (data not shown). The low level of thymic infection demonstrated here suggests that latently infected cells may arise primarily from reversion of activated peripheral CD4+ T cells to a resting state rather than from the export of infected thymocytes.

In the treated animals, replication-competent virus was isolated from resting CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood before the initiation of treatment but not after the treatment started (98P004 and 98P008) (Fig. 4A). The decreased frequency of replication-competent virus in resting cells during successful treatment probably results from a decreased number of cells harboring virus in a labile state of preintegration latency (4, 5, 42) rather than from a decreased number of cells in postintegration latency. Virus was recovered from the lymph nodes of animal 98P008 even when the infection was well suppressed (Fig. 4B). In the lymph node samples, there was a similar decrease of replication-competent virus (Fig. 4B), but virus remained recoverable after treatment, perhaps due to the fact that a greater number of purified resting lymphocytes could be obtained from the lymph nodes than from peripheral blood, facilitating virus recovery. In addition, integrated SIV DNA was readily detectible in PBMC from the successfully treated animal 98P008 (Fig. 5B and C). The recovery of replication-competent virus from lymph node cells of treated animal 98P008, along with the evidence for integrated virus in resting T cells in the lymph node of this animal (Fig. 5B and C), indicates that a latent reservoir in the resting CD4+ T lymphocytes exists in this animal model. Interestingly, macaque 98P008 was also the animal that had the most lymphoid depletion in spleen and lymph nodes. This suggests one of two possibilities: either lymphoid depletion was initiated by events occurring early in infection, prior to the initiation of treatment (98P008 had the highest set-point viral load before treatment), or there was a low level of localized viral recrudescence in the lymph nodes, resulting in ongoing lymph node damage and depletion.

Viral DNA was readily detectable in resting CD4+ T cells in tissues harboring mature T cells (Fig. 6). In the viremic animal 98P009, the spleen had the most virus (Fig. 4C and 6), while resting CD4+ T cells in the blood and lymph nodes had lower but readily measurable amounts of virus; in the aviremic animals, spleen and lymph nodes also had substantial amounts of virus (Fig. 4C, 5, and 6). These data suggest that spleen and lymph nodes along with PBMC are significant reservoir sites for the latently infected resting CD4+ T lymphocytes. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that splenectomy in HIV-1-infected patients (3) as well as SIV-infected macaques (26) results in reduced viral load, improved CD4 counts, and longer survival time. Our data also support the idea that the spleen is a major site for virus replication as well as a reservoir site.

Viral infection of the thymocytes, in contrast, was not observed to a significant degree in this model. The inaccessibility of the thymus has hindered analysis of the extent to which thymocytes are targeted by HIV-1 in vivo. Current notions of HIV-1 infection of the thymus are based on in vitro experiments (47), a model system involving SCID mice grafted with fetal-human thymus and liver (7, 8), postmortem observations (23), and studies with the SIV-macaque system. Baskin et al. demonstrated the presence of SIV in the thymi of rhesus macaques at as early as 2 weeks postinfection (2). According to culture assays, infected cells were present at frequencies of 101 to 104 IUPM, substantially higher than was observed in our study. However, these animals were not treated and were probably highly viremic, as evidenced by the presence of SIV antigenemia. Muller and colleagues demonstrated only low levels of infection of thymocytes (<1/10,000) in SIV-infected juvenile rhesus macaques (35). However, significant effects on critical thymic stromal elements were observed. Early entry of SIV into the thymi of infected rhesus monkeys has also been reported by Lackner et al. (30). Additional studies have documented complex effects on thymocyte apoptosis early in the course of SIV infection of rhesus monkeys (45, 53). Li et al. have demonstrated characteristic pathological changes and the presence of viral nucleic acid in thymi of SIV-infected cynomolgus monkeys (33). Thus, there is substantial evidence for the entry of SIV into thymic tissue in infected rhesus and cynomolgus monkeys. A critical difference is that most of the primate studies cited above have used animals that were highly viremic and even antigenemic. Ours is the first study to compare levels of infection of thymocytes and peripheral T cells in animals in which viremia was controlled to relatively low levels. We perfused the animals at necropsy to prevent contamination with cells from the blood. We found that in the setting of low viremia, persistence of the virus can be more easily demonstrated in resting peripheral CD4+ T cells than in thymocytes. It is also important to point out that some of the studies cited above have used in situ hybridization and/or immunohistochemical staining to demonstrate the infection in the thymus, without examining the different subpopulations of the thymocytes separately. In this study, we specifically examined two purified subpopulations from the thymus, the CD4 single-positive cells and the CD4/CD8 double-positive cells. No virus or viral DNA could be detected in the more immature CD4/CD8 double-positive cells (Fig. 4C and 6). The very small amount of virus and viral DNA detected in the more mature CD4 single-positive cells could represent mature T cells in the thymic medulla. In fact, several studies have noted that infection is most prominent among nonlymphoid cells in the cortex and among lymphocytes and macrophages in the medulla (2, 30, 53).

Further studies on the expression of SIV coreceptors on thymocytes suggested that the thymocytes might not be good targets for SIV infection due to low expression of CCR5 (Fig. 7). SIV mainly uses CCR5 as a coreceptor for viral infection of the host cell, but CCR5 was only expressed on very low percentages of the thymocytes. This is consistent with findings of low CCR5 expression (<5%) in human thymocytes (51, 55). Taken together, these observations suggest that, compared with mature CD4+ T cells in the peripheral lymphoid tissues, developing thymocytes do not contribute significantly to viral persistence in this system. However, it is possible that the low levels of infection in the thymocytes observed here may reflect some unique aspect of the viral clone used in this study or the pig-tailed macaque host. In addition, it should be noted that in HIV-1-infected humans, particularly those in whom X4 virus has developed, the extent of thymocyte infection may be different from that observed in this SIV model.

In summary, this study provides initial evidence for the utility of the SIV-macaque model for the analysis of viral persistence in the setting of HAART. Although the number of animals subjected to this complex protocol was by necessity small, the results confirm for another primate lentivirus the concept that latently infected resting CD4+ T cells can serve as a long-term reservoir for the virus despite effective suppression of viremia with treatment. This study also demonstrates the utility of this model in providing a complete systemic picture of the distribution and characteristics of residual virus persisting in the face of antiretroviral therapy. It is hoped that this model will be useful in the preclinical evaluation of novel strategies for targeting viral reservoirs that serve as a major barrier to HIV-1 eradication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Triangle Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for the gift of FTC and Gilead Sciences, Inc., for the gift of PMPA. We also thank Bruce Baldwin, Jennifer Bennett, Brandon Bullock, Jesse DeWitt, Laurie Queen, Suzanne Queen, Lily Lo, and Joleen Kajdas for excellent technical assistance; Douglas Richman, Christopher Buck, Ted Pierson, and R. Lee Blosser for valuable advice; and Daphne Monie and Darryl Carter for helpful discussions. We also acknowledge Russ Byrum and the excellent staff at Bioqual Inc. for exceptional animal care.

This study was funded by NIH grants to R.F.S., M.C.Z., and J.E.C. (AI43222, MH61189, NS35751, NS38008, and NS36911).

REFERENCES

- 1.Balzarini, J., L. Naesens, and E. De Clercq. 1990. Anti-retrovirus activity of 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA) in vivo increases when it is less frequently administered. Int. J. Cancer 46:337-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baskin, G. B., M. Murphey-Corb, L. N. Martin, B. Davison-Fairburn, F. S. Hu, and D. Kuebler. 1991. Thymus in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. Lab. Investig. 65:400-407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard, N. F., D. N. Chernoff, and C. M. Tsoukas. 1998. Effect of splenectomy on T-cell subsets and plasma HIV viral titers in HIV-infected patients. J. Hum. Virol. 1:338-345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blankson, J. N., D. Finzi, T. C. Pierson, B. P. Sabundayo, K. Chadwick, J. B. Margolick, T. C. Quinn, and R. F. Siliciano. 2000. Biphasic decay of latently infected CD4+ T cells in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1636-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankson, J. N., J. E. Gallant, and R. F. Siliciano. 2001. Proliferative responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antigens in HIV-1-infected patients with immune reconstitution. J. Infect. Dis. 183:657-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankson, J. N., D. Persaud, and R. F. Siliciano. 2002. The challenge of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 infection. Annu. Rev. Med. 53:557-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonyhadi, M. L., L. Rabin, S. Salimi, D. A. Brown, J. Kosek, J. M. McCune, and H. Kaneshima. 1993. HIV induces thymus depletion in vivo. Nature 363:728-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks, D. G., S. G. Kitchen, C. M. Kitchen, D. D. Scripture-Adams, and J. A. Zack. 2001. Generation of HIV latency during thymopoiesis. Nat. Med. 7:459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bukrinsky, M. I., T. L. Stanwick, M. P. Dempsey, and M. Stevenson. 1991. Quiescent T lymphocytes as an inducible virus reservoir in HIV-1 infection. Science 254:423-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun, T.-W., D. Finzi, J. Margolick, K. Chadwick, D. Schwartz, and R. F. Siliciano. 1995. In vivo fate of HIV-1-infected T cells: quantitative analysis of the transition to stable latency. Nat. Med. 1:1284-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chun, T. W., L. Carruth, D. Finzi, X. Shen, J. A. DiGiuseppe, H. Taylor, M. Hermankova, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, T. C. Quinn, Y. H. Kuo, R. Brookmeyer, M. A. Zeiger, P. Barditch-Crovo, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature 387:183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun, T. W., L. Stuyver, S. B. Mizell, L. A. Ehler, J. M. Mican, M. Baseler, A. L. Lloyd, M. A. Nowak, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13193-13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douek, D. C., M. R. Betts, B. J. Hill, S. J. Little, R. Lempicki, J. A. Metcalf, J. Casazza, C. Yoder, J. W. Adelsberger, R. A. Stevens, M. W. Baseler, P. Keiser, D. D. Richman, R. T. Davey, and R. A. Koup. 2001. Evidence for increased T cell turnover and decreased thymic output in HIV infection. J. Immunol. 167:6663-6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duh, E. J., W. J. Maury, T. M. Folks, A. S. Fauci, and A. B. Rabson. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor alpha activates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 through induction of nuclear factor binding to the NF-κB sites in the long terminal repeat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:5974-5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finzi, D., J. Blankson, J. D. Siliciano, J. B. Margolick, K. Chadwick, T. Pierson, K. Smith, J. Lisziewicz, F. Lori, C. Flexner, T. C. Quinn, R. E. Chaisson, E. Rosenberg, B. Walker, S. Gange, J. Gallant, and R. F. Siliciano. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 5:512-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finzi, D., M. Hermankova, T. Pierson, L. M. Carruth, C. Buck, R. E. Chaisson, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, R. Brookmeyer, J. Gallant, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. Richman, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flaherty, M. T., D. A. Hauer, J. L. Mankowski, M. C. Zink, and J. E. Clements. 1997. Molecular and biological characterization of a neurovirulent molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 71:5790-5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox, H. S., M. R. Weed, S. Huitron-Resendiz, J. Baig, T. F. Horn, P. J. Dailey, N. Bischofberger, and S. J. Henriksen. 2000. Antiviral treatment normalizes neurophysiological but not movement abnormalities in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected monkeys. J. Clin. Investig. 106:37-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaulton, G. N., J. V. Scobie, and M. Rosenzweig. 1997. HIV-1 and the thymus. AIDS 11:403-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulick, R. M., J. W. Mellors, D. Havlir, J. J. Eron, C. Gonzalez, D. McMahon, D. D. Richman, F. T. Valentine, L. Jonas, A. Meibohm, E. A. Emini, and J. A. Chodakewitz. 1997. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:734-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammer, S. M., K. E. Squires, M. D. Hughes, J. M. Grimes, L. M. Demeter, J. S. Currier, J. J. Eron, Jr., J. E. Feinberg, H. H. Balfour, Jr., L. R. Deyton, J. A. Chodakewitz, M. A. Fischl, et al. 1997. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:725-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havlir, D. V., R. Bassett, D. Levitan, P. Gilbert, P. Tebas, A. C. Collier, M. S. Hirsch, C. Ignacio, J. Condra, H. F. Gunthard, D. D. Richman, and J. K. Wong. 2001. Prevalence and predictive value of intermittent viremia with combination HIV therapy. JAMA 286:171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes, B. F., M. L. Markert, G. D. Sempowski, D. D. Patel, and L. P. Hale. 2000. The role of the thymus in immune reconstitution in aging, bone marrow transplantation, and HIV-1 infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:529-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsch, V. M., T. R. Fuerst, G. Sutter, M. W. Carroll, L. C. Yang, S. Goldstein, M. Piatak, Jr., W. R. Elkins, W. G. Alvord, D. C. Montefiori, B. Moss, and J. D. Lifson. 1996. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J. Virol. 70:3741-3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch, V. M., and J. D. Lifson. 2000. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of monkeys as a model system for the study of AIDS pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. Adv. Pharmacol. 49:437-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joag, S. V., E. B. Stephens, R. J. Adams, L. Foresman, and O. Narayan. 1994. Pathogenesis of SIVmac infection in Chinese and Indian rhesus macaques: effects of splenectomy on virus burden. Virology 200:436-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan, A., P. Defechereux, and E. Verdin. 2001. The site of HIV-1 integration in the human genome determines basal transcriptional activity and response to Tat transactivation. EMBO J. 20:1726-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korin, Y. D., D. G. Brooks, S. Brown, A. Korotzer, and J. A. Zack. 2002. Effects of prostratin on T-cell activation and human immunodeficiency virus latency. J. Virol. 76:8118-8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulkosky, J., D. M. Culnan, J. Roman, G. Dornadula, M. Schnell, M. R. Boyd, and R. J. Pomerantz. 2001. Prostratin: activation of latent HIV-1 expression suggests a potential inductive adjuvant therapy for HAART. Blood 98:3006-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lackner, A. A., P. Vogel, R. A. Ramos, J. D. Kluge, and M. Marthas. 1994. Early events in tissues during infection with pathogenic (SIVmac239) and nonpathogenic (SIVmac1A11) molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Pathol. 145:428-439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Letvin, N. L., D. H. Barouch, and D. C. Montefiori. 2002. Prospects for vaccine protection against HIV-1 infection and AIDS. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:73-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, S. L., E. E. Kaaya, C. Ordonez, M. Ekman, H. Feichtinger, P. Putkonen, D. Bottiger, G. Biberfeld, and P. Biberfeld. 1995. Thymic immunopathology and progression of SIVsm infection in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 9:1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lori, F., M. G. Lewis, J. Xu, G. Varga, D. E. Zinn, Jr., C. Crabbs, W. Wagner, J. Greenhouse, P. Silvera, J. Yalley-Ogunro, C. Tinelli, and J. Lisziewicz. 2000. Control of SIV rebound through structured treatment interruptions during early infection. Science 290:1591-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mankowski, J. L., M. T. Flaherty, J. P. Spelman, D. A. Hauer, P. J. Didier, A. M. Amedee, M. Murphey-Corb, L. M. Kirstein, A. Munoz, J. E. Clements, and M. C. Zink. 1997. Pathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis: viral determinants of neurovirulence. J. Virol. 71:6055-6060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller, J. G., V. Krenn, C. Schindler, S. Czub, C. Stahl-Hennig, C. Coulibaly, G. Hunsmann, C. Kneitz, T. Kerkau, A. Rethwilm, et al. 1993. Alterations of thymus cortical epithelium and interdigitating dendritic cells but no increase of thymocyte cell death in the early course of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Am. J. Pathol. 143:699-713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myers, L. E., L. J. McQuay, and F. B. Hollinger. 1994. Dilution assay statistics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:732-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nabel, G., and D. Baltimore. 1987. An inducible transcription factor activates expression of human immunodeficiency virus in T cells. Nature 326:711-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perelson, A. S., P. Essunger, Y. Cao, M. Vesanen, A. Hurley, K. Saksela, M. Markowitz, and D. D. Ho. 1997. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 387:188-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Persaud, D., T. Pierson, C. Ruff, D. Finzi, K. R. Chadwick, J. B. Margolick, A. Ruff, N. Hutton, S. Ray, and R. F. Siliciano. 2000. A stable latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4(+) T lymphocytes in infected children. J. Clin. Investig. 105:995-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierson, T., T. L. Hoffman, J. Blankson, D. Finzi, K. Chadwick, J. B. Margolick, C. Buck, J. D. Siliciano, R. W. Doms, and R. F. Siliciano. 2000. Characterization of chemokine receptor utilization of viruses in the latent reservoir for HIV-1. J. Virol. 74:7824-7833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierson, T., J. McArthur, and R. F. Siliciano. 2000. Reservoirs for HIV-1: mechanisms for viral persistence in the presence of antiviral immune responses and antiretroviral therapy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:665-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierson, T. C., Y. Zhou, T. L. Kieffer, C. T. Ruff, C. Buck, and R. F. Siliciano. 2002. Molecular characterization of preintegration latency in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 76:8518-8531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramratnam, B., J. E. Mittler, L. Zhang, D. Boden, A. Hurley, F. Fang, C. A. Macken, A. S. Perelson, M. Markowitz, and D. D. Ho. 2000. The decay of the latent reservoir of replication competent HIV-1 is inversely correlated with the extent of residual viral replication during prolonged antiretroviral therapy. Nat. Med. 6:82-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roederer, M., J. G. Dubs, M. T. Anderson, P. A. Raju, and L. A. Herzenberg. 1995. CD8 naive T cell counts decrease progressively in HIV-infected adults. J. Clin. Investig. 95:2061-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenzweig, M., M. Connole, A. Forand-Barabasz, M. P. Tremblay, R. P. Johnson, and A. A. Lackner. 2000. Mechanisms associated with thymocyte apoptosis induced by simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Immunol. 165:3461-3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schinazi, R. F., F. D. Boudinot, S. S. Ibrahim, C. Manning, H. M. McClure, and D. C. Liotta. 1992. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of racemic 2′,3′-dideoxy-5-fluoro-3′-thiacytidine in rhesus monkeys. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2432-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnittman, S. M., S. M. Denning, J. J. Greenhouse, J. S. Justement, M. Baseler, J. Kurtzberg, B. F. Haynes, and A. S. Fauci. 1990. Evidence for susceptibility of intrathymic T-cell precursors and their progeny carrying T-cell antigen receptor phenotypes TCRαβ+ and TCRγδ+ to human immunodeficiency virus infection: a mechanism for CD4+ (T4) lymphocyte depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:7727-7731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma, D. P., M. C. Zink, M. Anderson, R. Adams, J. E. Clements, S. V. Joag, and O. Narayan. 1992. Derivation of neurotropic simian immunodeficiency virus from exclusively lymphocytetropic parental virus: pathogenesis of infection in macaques. J. Virol. 66:3550-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su, L., H. Kaneshima, M. Bonyhadi, S. Salimi, D. Kraft, L. Rabin, and J. M. McCune. 1995. HIV-1-induced thymocyte depletion is associated with indirect cytopathogenicity and infection of progenitor cells in vivo. Immunity 2:25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suryanarayana, K., T. A. Wiltrout, G. M. Vasquez, V. M. Hirsch, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Plasma SIV RNA viral load determination by real-time quantification of product generation in reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor, J. R., Jr., K. C. Kimbrell, R. Scoggins, M. Delaney, L. Wu, and D. Camerini. 2001. Expression and function of chemokine receptors on human thymocytes: implications for infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:8752-8760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong, J. K., M. Hezareh, H. F. Gunthard, D. V. Havlir, C. C. Ignacio, C. A. Spina, and D. D. Richman. 1997. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science 278:1291-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wykrzykowska, J. J., M. Rosenzweig, R. S. Veazey, M. A. Simon, K. Halvorsen, R. C. Desrosiers, R. P. Johnson, and A. A. Lackner. 1998. Early regeneration of thymic progenitors in rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Exp. Med. 187:1767-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zack, J. A., S. J. Arrigo, S. R. Weitsman, A. S. Go, A. Haislip, and I. S. Y. Chen. 1990. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell 61:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zamarchi, R., P. Allavena, A. Borsetti, L. Stievano, V. Tosello, N. Marcato, G. Esposito, V. Roni, C. Paganin, G. Bianchi, F. Titti, P. Verani, G. Gerosa, and A. Amadori. 2002. Expression and functional activity of CXCR-4 and CCR-5 chemokine receptors in human thymocytes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 127:321-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]