Abstract

In this work, the role of jasmonic acid (JA) in leaf senescence is examined. Exogenous application of JA caused premature senescence in attached and detached leaves in wild-type Arabidopsis but failed to induce precocious senescence of JA-insensitive mutant coi1 plants, suggesting that the JA-signaling pathway is required for JA to promote leaf senescence. JA levels in senescing leaves are 4-fold higher than in non-senescing ones. Concurrent with the increase in JA level in senescing leaves, genes encoding the enzymes that catalyze most of the reactions of the JA biosynthetic pathway are differentially activated during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis, except for allene oxide synthase, which is constitutively and highly expressed throughout leaf development. Arabidopsis lipoxygenase 1 (cytoplasmic) expression is greatly increased but lipoxygenase 2 (plastidial) expression is sharply reduced during leaf senescence. Similarly, AOC1 (allene oxide cyclase 1), AOC2, and AOC3 are all up-regulated, whereas AOC4 is down-regulated with the progression of leaf senescence. The transcript levels of 12-oxo-PDA reductase 1 and 12-oxo-PDA reductase 3 also increase in senescing leaves, as does PED1 (encoding a 3-keto-acyl-thiolase for β-oxidation). This represents the first report, to our knowledge, of an increase in JA levels and expression of oxylipin genes during leaf senescence, and indicates that JA may play a role in the senescence program.

Originally identified as a major component of fragrant oils, methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and its precursor jasmonic acid (JA) were first demonstrated to promote senescence in detached oat (Avena sativa) leaves (Ueda and Kato, 1980), and were subsequently shown to be a class of plant growth regulator that plays pervasive roles in several other aspects of plant development, including seed germination and pollen development, responses to mechanical and insect wounding, pathogen infection, and drought stress (for review, see Hildebrand et al., 1998; Schaller, 2001). Recent molecular genetic studies have confirmed the involvement of JA both in developmental (Xie et al., 1998; Sanders et al., 2000; Stintzi and Browse, 2000) and defense-related processes (Vijayan et al., 1998; Xie et al., 1998; Ryan, 2000). The role of JA in leaf senescence is not clear. Exogenously applied JA and MeJA led to decreased expression of photosynthesis-related genes encoding, for example, the small subunit of Rubisco, reduced translation and increased degradation of Rubisco, and rapid loss of chlorophyll in barley (Hordeum vulgare) leaves (Weidhase et al., 1987; Parthier, 1990). However, many questions remain unanswered, such as whether JA levels change in leaves undergoing senescence and whether specific genes of JA biosynthesis are induced during senescence.

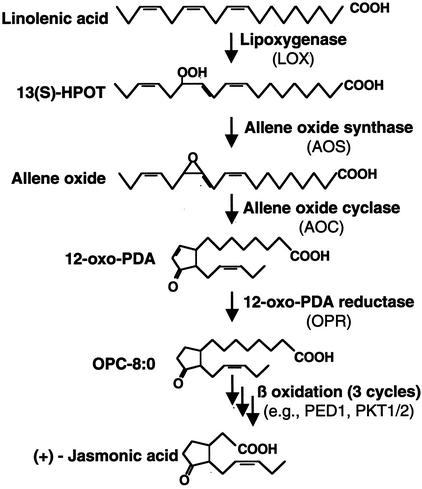

The biosynthetic pathway of JA, starting with α-linolenic acid, has been elucidated (Fig. 1; Vick and Zimmerman, 1984; Schaller, 2001). There may exist two pathways for JA biosynthesis in plant tissues, a chloroplast-localized and a cytoplasm-localized pathway (Creelman and Mullet, 1995). The existence of a cytoplasmic pathway is suggested by a transgenic study involving overexpression of a cytosolic allene oxide synthase (AOS) in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Wang et al., 1999). JA biosynthesis is tightly regulated and the concentrations of JA in uninduced plant tissues are generally very low in most plant species examined (Hildebrand et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000). In addition, JA biosynthesis is subject to inductive control by various elicitors such as wounding (Hildebrand et al., 2000; Ryan, 2000; Wang et al., 2000). The expressions of several genes, including lipoxygenase (LOX) and AOS, were increased by exogenous application of JA and associated with an increased level of endogenous JA (Bell and Mullet, 1993; Melan et al., 1993; Laudert and Weiler, 1998; Maucher et al., 2000), indicating that JA biosynthesis is also subject to auto-induction (Schaller, 2001). However, the biosynthesis of JA during leaf senescence has not been characterized.

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic pathway of JA. 13(S)-HPOT, (9Z,11E,15Z,13S)- 13-hydroperoxy-9,11,15-octadecatrienoic acid; 12-oxo-PDA, 12-oxo-10,15(Z)-octadecatrienoic acid; PED1, peroxisome defective 1, a 3-keto-acyl-thiolase; PKT1/2, 3-keto-acyl-thiolase 1 and 2; OPC-8:0, 3-oxo-2(2′(Z)-pentenyl)-cyclopentane-1-octanoic acid.

Here, we report that exogenous JA promotes typical senescence in both attached and detached Arabidopsis leaves but fails to induce precocious leaf senescence in the JA-insensitive mutant coi1, and that the endogenous JA levels in senescing Arabidopsis leaves are nearly 4-fold higher than that in fully expanded, non-senescing (NS) leaves. Consistent with an increased JA level in senescing leaves, genes encoding enzymes in the JA biosynthesis pathway are differentially activated during leaf senescence. These data suggest that JA has a role in leaf senescence in Arabidopsis.

RESULTS

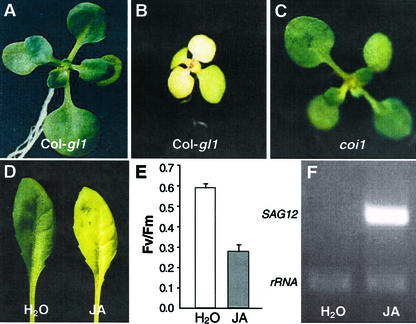

JA Induces Precocious Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis

To investigate the potential role of JA in leaf senescence, we treated Arabidopsis with JA. After growth on agar medium containing 30 μm JA for 12 d, expanding leaves (ELs) of Arabidopsis plants (ecotype Columbia-glabrous [Col-gl1]) displayed precocious senescence symptoms as indicated by visible yellowing (Fig. 2B). In contrast, leaves of Arabidopsis plants grown on the same medium without JA did not exhibit any senescence symptoms (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, coi1, a JA-insensitive mutant with the genetic background of Col-gl1 (Xie et al., 1998), did not undergo precocious senescence in the presence of JA (Fig. 2C), which demonstrated that the JA-responsive pathway is required for JA-promoted leaf senescence. It should be noted that natural leaf senescence in coi1 plants was not delayed compared with that of Col-gl1 (Y. He and S. Gan, unpublished data).

Figure 2.

Promotion of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis by JA. Wild-type Col-gl1 (A and B) and JA-insensitive mutant coi1 plants (C) were grown on phytoagar medium containing 0 (A) or 30 (B and C) μm JA for 12 d. D, Detached young Col-gl1 leaves treated with water or 30 μm JA for 4 d under darkness. E, Variable fluorescence (Fv)/maximal fluorescence (Fm) values of leaves shown in D. F, Expression of the senescence-specific marker gene SAG12 in leaves shown in D.

JA also promoted senescence in detached Arabidopsis leaves (Fig. 2D). Consistent with the visible yellowing, the photochemical quantum efficiency of photosystem II reaction center (Fv/Fm) in JA-treated leaves is much lower than that in control (Fig. 2E). To further investigate if the yellowing is a senescence process, we extracted total RNA from these leaves, and performed reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis of the expression of SAG12. SAG12 is a senescence-specific gene in Arabidopsis (Gan, 1995) that has been widely used as a molecular marker for leaf senescence (e.g. Weaver et al., 1998; Ludewig and Sonnewald, 2000; Morris et al., 2000; Hinderhofer and Zentgraf, 2001; Woo et al., 2001), but not for the hypersensitive reaction (Pontier et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 2F, SAG12 accumulated only in the leaves induced to become yellow by JA.

JA Level Increases in Senescing Leaves

The fact that JA treatment promoted senescence in attached and detached Arabidopsis leaves prompted us to investigate whether the endogenous JA level increases in senescing leaves. Total JA in fully expanded, NS leaves and in leaves at the early senescence stage (ES; these leaves showed up to 25% yellowing) of Arabidopsis was extracted and quantified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). As shown in Table I, the level of JA in ES leaves (130.0 pmol g fresh weight−1) is 4.7-fold higher than that in NS leaves (27.7 pmol g fresh weight−1). In contrast, the levels of OPDA in ES leaves (485.3 pmol g fresh weight−1) is less than one-half of that in NS leaves (1,143.0 pmol g fresh weight−1).

Table I.

Levels of JA and 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA) in Arabidopsis leaves

| Chemicals | NS (Four Replications) | ES (Three Replications) |

|---|---|---|

| pmol g fresh wt−1 | ||

| JA | 27.7 ± 4.5 | 130.0 ± 14.7 |

| OPDA | 1,143.0 ± 292.1 | 485.3 ± 134.2 |

JA-Dependent Marker Gene PDF1.2 Is Up-Regulated during Leaf Senescence

PDF1.2 has been widely used as a JA-responsive marker gene (e.g. Penninckx et al., 1996; Moran and Thompson, 2001), which might be induced in response to an elevated JA level in senescing leaves. Therefore, we performed RT-PCR analysis using PDF1.2-specific primers (compare with Table II) to assess the transcript levels of this gene in leaves at the following four developmental stages: ELs (showing one-half size of fully expanded leaves); fully expanded, NS leaves; leaves at ES (up to 25% of a leaf shows yellowing); and at late-senescence stage (LS, more than 50% of a leaf shows yellowing). As shown in Figure 3, the level of PDF1.2 transcript increased 5.1- and 6.4-fold in ES and LS leaves, respectively, relative to that in NS leaves.

Table II.

Primers used in this paper

| Primer No. | Nucleotide Sequences (from 5′ to 3′) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CCACACGGATTACGTCTGAG | Nos. 1 and 2 used for LOX1 northern-probe amplification |

| 2 | CCCTGCCGGTGACTCCGC | |

| 3 | CCGAGTTTTGACCCGTCCG | Nos. 3 and 4 used for AOS northern-probe amplification |

| 4 | ACTTGATGACCCGCCCGCC | |

| 5 | GAGGACCCTGAAGCTCATTG | Nos. 5 and 6 used for PKT1/2 northern-probe amplification |

| 6 | TCACGGGCTTTTGGGAAATC | |

| 7 | AGGACTTCCCGTTCTTGGTG | Nos. 7 and 8 used for PED1 northern-probe amplification |

| 8 | GGCTGCCACCCAAAAAATCT | |

| 9 | GACCGGAGACAGAAAGAGCG | Nos. 9 and 10 used for LOX3 RT-PCR |

| 10 | CATGCGTTTTTATCCTTCGATAA | |

| 11 | GTCGGTAGAAAACAAGAGAAG | Nos. 11 and 12 used for LOX4 RT-PCR |

| 12 | CCATGCATATTTATCCTTTGAAAC | |

| 13 | GACTAATTTTATTCACTAATTT | Nos. 13 and 14 used for AtAOC1 RT-PCR |

| 14 | CCCCAGACCAAGCAAAGT | |

| 15 | AAACAACTATTAAACAGCTAAT | Nos. 15 and 16 used for AtAOC2 RT-PCR |

| 16 | AACTCCAGACCAAGTAAGAT | |

| 17 | GATACGAGAAACATTTTAATTTCA | Nos. 17 and 18 used for AtAOC3 RT-PCR |

| 18 | CCCTAGACCAAGCAAAGTT | |

| 19 | CTCCAGACCAACTAAGATCC | Nos. 19 and 20 used for AtAOC4 RT-PCR |

| 20 | CAACAGCCCAATAAGATCC | |

| 21 | TACAGCTCAAGGATATCAAGA | Nos. 21 and 22 used for OPR1 RT-PCR |

| 22 | GAAACTTATTACATCTTATATAA | |

| 23 | CTATGGAAGCTGGTTTTGATGGAG | Nos. 23 and 24 used for OPR2 RT-PCR |

| 24 | ATAATGACTTAGAGTATAAACAA | |

| 25 | CTTCTCATGCAGTGTATCAAC | Nos. 25 and 26 used for OPR3 RT-PCR |

| 26 | CGTCCAAGTGATCTATAGCTG | |

| 27 | CAGCTGCGGATGTTGTTG | Nos. 27 and 28 used for SAG12 RT-PCR |

| 28 | CCACTTTCTCCCCATTTTG |

Figure 3.

RT-PCR analysis of the expression of JA-responsive marker gene PDF1.2 during leaf senescence. EL, About 50% of the fully expanded leaves; NS, fully expanded, NS leaves; ES, up to 25% of a leaf shows yellowing; LS, more than 50% of a leaf shows yellowing.

Genes Encoding Enzymes for JA Biosynthesis Are Differentially Activated during Leaf Senescence

We further investigated the molecular basis underlying the elevated JA level in senescing leaves. As shown in Figure 1, the biosynthesis of JA starts with α-linolenic acid, which is converted to its 13(S)-hydroperoxide by 13-LOX; the LOX product is subsequently converted to OPDA by sequential actions of AOS and allene oxide cyclase (AOC). OPDA is further reduced to form 3-oxo-2-cyclopentane-1-octanoic acid (OPC-8:0) by 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase (OPR). After three cycles of β-oxidation, (+) 7-iso-JA is formed (Vick and Zimmerman, 1984; Schaller, 2001). We used RNA gel-blot and RT-PCR analyses to examine the steady-state mRNA levels of these JA biosynthesis-related genes in leaves at the four developmental stages described for the PDF1.2 analyses.

LOX

There are at least four LOX genes in the Arabidopsis genome. The nucleic acid sequence of LOX1 is divergent from the LOX2 sequence so that probes do not cross hybridize with each other (Bell and Mullet, 1993), whereas LOX3 (GenBank accession no. AJ249794) and LOX4 (GenBank accession no. AJ302042) share high homology. Thus, we used RNA gel-blot analysis to assess the expression of LOX1 and LOX2, and RT-PCR involving gene-specific primers to analyze the transcript levels of LOX3 and LOX4. As shown in Figure 4A, LOX1, considered to be located in cytoplasm (Melan et al., 1993), was strongly up-regulated during leaf senescence. Consistent with previous reports (Bell and Mullet, 1993; Melan et al., 1993; Moran and Thompson, 2001), there were barely detectable signals in leaves before senescence (Fig. 4A). In contrast, LOX2, a plastidial stroma-localized LOX (Bell and Mullet, 1993; Creelman and Mullet, 1997), was sharply down-regulated (Fig. 4A). It is interesting that although LOX3 and LOX4, like LOX2, contain chloroplast transit peptide sequences and are believed to be plastidial, both genes (LOX3 and LOX4) were up-regulated with the progression of leaf senescence: The abundance of LOX3 transcript in ES and LS leaves is 3-fold of that in NS leaves, whereas the mRNA levels of LOX4 in ES and LS leaves are 7.3 and 5.4 times of that in NS leaves (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of LOXs during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. A, RNA gel-blot analysis of LOX1 and LOX2. B, RT-PCR analysis of LOX3 and LOX4. EL, NS, ES, and LS are as described in legend to Figure 3.

AOS

The next gene in the JA biosynthesis pathway is AOS (Fig. 1) Unlike LOX, there exists only one AOS in the Arabidopsis genome. As shown in Figure 5, AOS was expressed at a relatively high level throughout leaf development, and was slightly up-regulated during leaf senescence.

Figure 5.

Constitutive expression of AOS throughout leaf development. EL, NS, ES, and LS are as described in legend to Figure 3.

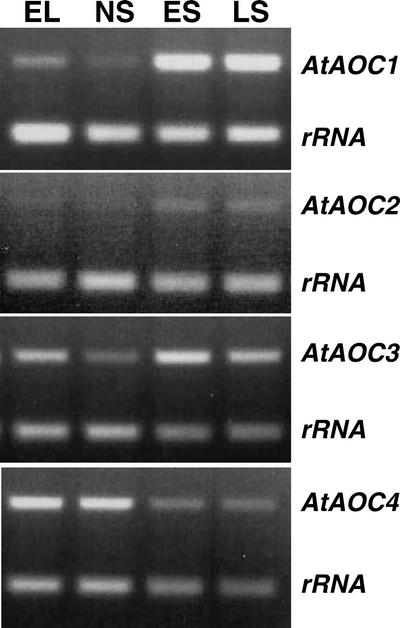

AOC

AOC catalyzes the stereospecific cyclization of allene oxide to OPDA, thus establishing the stereochemistry of OPDA and JA (Vick and Zimmerman, 1984; Ziegler et al., 2000). AOC been has recently isolated from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum; Ziegler et al., 2000). Using the amino acid sequence of tomato AOC protein to search the Arabidopsis genome database, we found four annotated AOC genes in the genome. Furthermore, using these four annotated AOC nucleotide sequences to search the Arabidopsis expressed sequence tag database, three of four were found to match related ESTs. We refer to these AOCs as AtAOC1 (accession no. BAA95763), AtAOC2 (accession no. BAA95765), AtAOC3 (accession no. BAA95764), and AtAOC4 (accession no. AAG09557). Because of high sequence similarity among the cDNA regions of these AtAOCs, a pair of primers specific for each AtAOC (compare with Table II) were synthesized for RT-PCR analysis. The RT-PCR products were directly sequenced, and the results showed that each AtAOC was specifically amplified using the corresponding pair of primers (data not shown). Figure 6 shows that during leaf senescence, AtAOC1 is strongly up-regulated, and AtAOC2 is moderately up-regulated but its transcript abundance in leaves before senescence is very low. In contrast, AtAOC4 is down-regulated. It is interesting that AtAOC3 expression in ELs is relatively high, relatively low in NS leaves, and moderately up-regulated again during leaf senescence (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

RT-PCR analysis of the expression of AOCs during leaf senescence. EL, NS, ES, and LS are as described in legend to Figure 3.

OPR

Three OPR genes (OPR1, OPR2, and OPR3) have been isolated from Arabidopsis (Biesgen and Weiler, 1999; Sanders et al., 2000; Stintzi and Browse, 2000), and it has been reported that OPR3 is the major reductase converting OPDA to OPC-8:0 (Schaller et al., 2000). Because of the high sequence similarity between OPR1 and OPR2 (Biesgen and Weiler, 1999) as well as the sequence homology among OPR1, OPR2, and OPR3 (Sanders et al., 2000; Stintzi and Browse, 2000), the gene-specific primers for each OPR (compare with Table II) were used for RT-PCR analysis. As shown in Figure 7, both OPR3 and OPR1 are up-regulated during leaf senescence, especially in ES leaves: There are 2.9-fold (OPR1) and 2.3-fold (OPR3) increases relative to respective transcript abundance in NS leaves. In contrast, OPR2 appears to be constitutively expressed through these four stages of leaf development.

Figure 7.

RT-PCR analysis of the expression of OPRs during leaf senescence. EL, NS, ES, and LS are as described in legend to Figure 3.

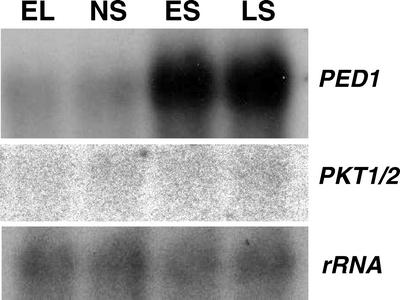

Thiolase

JA is believed to be synthesized from OPC-8:0 through three cycles of β-oxidation (Vick and Zimmerman, 1984; Schaller, 2001). Three 3-keto-acyl-thiolases, the enzyme responsible for β-oxidation, PED1, PKT1, and PKT2, have been identified from Arabidopsis (Rocha et al., 1996; Hayashi et al., 1998). PKT1 and PKT2 are encoded by the same genomic sequence (accession no. AF062589) and result from alternative splicing. PED1 (peroxisome defective) plays a key role in β-oxidation; a knockout of this thiolase causes defects in glyoxysomal fatty acid β-oxidation (Hayashi et al., 1998). PED1 has been shown to be involved in wounding-induced JA biosynthesis (M. Afitlhile and D.F. Hildebrand, unpublished data). RNA gel-blot analysis revealed that PED1 was strongly up-regulated during leaf senescence, whereas PKT1 and PKT2 were expressed at an extremely low level in these Arabidopsis leaves and could barely be detected in a 2-d exposed phosphoimage (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

RNA gel-blot analysis of thiolase genes during leaf senescence. EL, NS, ES, and LS are as described in legend to Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

A role for JA in leaf senescence has remained unclear. For example, transgenic potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants constitutively expressing a flax (Linum usitatissimum) AOS led to the overproduction of JA (Harms et al., 1995), but the authors did not report an ES phenotype in these transgenic plants. Also, the Arabidopsis triple mutant fad3-2 fad7-2 fad8 (Vijayan et al., 1998) and the OPR3 knockout mutants because of T-DNA insertion (Schaller et al., 2000; Stintzi and Browse, 2000) produced little JA, but no significantly delayed leaf senescence phenotype was reported; similarly, in our work no obvious alteration in senescence was observed in Arabidopsis mutants with impaired JA signaling (e.g. coi1). However, these facts may not necessarily contradict a senescence-promoting role of JA and derivatives. Although the transgenic potato plants accumulated a much higher level of JA, they did not display characteristic phenotypes such as the activation of JA-inducible genes. One plausible explanation is that the overproduced JA was sequestered so that it could not exert its biological action (Creelman and Mullet, 1997). On the other hand, it is not surprising that JA-underproducing Arabidopsis mutants did not exhibit a significantly retarded leaf senescence phenotype because of the plasticity of leaf senescence (Gan and Amasino, 1997). It is known that many environmental stresses and endogenous factors can induce leaf senescence; these multiple pathways interconnect to form a regulatory network to control leaf senescence (Gan and Amasino, 1997; He et al., 2001). Thus, blocking a particular pathway (e.g. the JA-induced pathway) may not have an obvious effect on the progression of senescence (Bleecker and Patterson, 1997; Gan and Amasino, 1997).

How might JA induce leaf senescence? It has been suggested that JA promotes leaf senescence at the transcriptional level by activating a subset of SAGs (senescence-associated genes; Parthier, 1990). It is generally accepted that leaf senescence is driven by the expression of SAGs (Bleecker and Patterson, 1997; Buchanan-Wollaston, 1997; Gan and Amasino, 1997; Hajouj et al., 2000; Quirino et al., 2000). Recent studies have revealed that a number of SAGs in Arabidopsis are up-regulated by JA or MeJA treatment. For example, MeJA induced expression of three SAGs (SEN4, SEN5, and rVPE; Park et al., 1998; Kinoshita et al., 1999). A micro-array analysis also revealed the induction of another six SAGs including SEN1, SAG14, and SAG15 (Schenk et al., 2000). We have identified 125 Arabidopsis enhancer trap lines in which the reporter gene GUS displayed senescence-associated expression in leaves, and we have found that GUS expression in 14 lines (14 of 125 lines or 11%) is induced upon JA treatment (He et al., 2001).

A senescence-promoting role might be associated with an elevated level of JA in senescing leaves. However, no quantitative analysis of JA pathway metabolite levels in senescing leaves has been performed (Creelman and Mullet, 1997). Our GC-MS analysis clearly showed that the JA level in early senescing leaves (up to 25% yellowing) is 5 times that in fully expanded, NS leaves in Arabidopsis (Table I).

The increase in JA level in senescing leaves is supported by our molecular findings that JA biosynthesis-related genes are differentially activated during leaf senescence (Figs. 4–8). It has been generally accepted that the initial steps of the JA biosynthesis pathway involving LOX, AOS, and AOC occur in chloroplasts (Schaller, 2001), which is well supported by studies involving the plastidial LOX2. LOX2 has been shown to play a role in wounding- and defense-related responses in Arabidopsis plants (Bell and Mullet, 1993; Creelman and Mullet, 1997); it is unlikely to be involved in JA biosysnthesis during senescence because its expression is turned off at the onset of leaf senescence (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the cytoplasmic LOX1 is strongly activated during leaf senescence (Fig. 4A), and is likely to be responsible for the increased JA production in senescing Arabidopsis leaves (Table I), although it is not known if the transcribed LOX1 is translated to active enzyme. Elevated LOX activities in senescing plant tissues have been repeatedly reported (for review, see Siedow, 1991). In addition to LOX1, the plastidial LOX3 and LOX4 are also up-regulated during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis (Fig. 4B) and thus may also contribute to JA biosynthesis in senescing leaves. Like LOX, there are four AOC genes in the Arabidopsis genome (this report), and three of them (AOC1–AOC3) are up-regulated, whereas AOC4 is down-regulated during leaf senescence (Fig. 6). To our knowledge, this is the first report on Arabidopsis AOCs, and their functionality needs to be further analyzed.

Recent studies have shown that OPR3 is involved in the biosynthesis of JA (Sanders et al., 2000; Schaller et al., 2000; Stintzi and Browse, 2000). This gene clearly is up-regulated during leaf senescence, especially at the early stage of leaf senescence (Fig. 7). In addition to OPR3, the transcript level of OPR1 also increases in senescing leaves, which is consistent with reporter gene studies that OPR1 promoter-directed reporter gene GUS accumulated in senescing Arabidopsis leaves (Biesgen and Weiler, 1999; Xie et al., 2001). Two cis elements are responsible for the accumulation of the OPR1 transcript during senescence (He and Gan, 2001). OPR2 appears to be constitutively expressed throughout the leaf development (Fig. 7). Whether OPR1 and OPR2 contribute to the accumulation of JA in senescing leaves remains unknown.

The final steps in the biosynthetic pathway of JA are believed to be three cycles of β-oxidation as supported by a study involving OPC derivatives (Miersch and Wasternack, 2000). Arabidopsis PED1 encodes a thiolase that is involved in the glyoxysomal fatty acid β-oxidation (Hayashi et al., 1998). PED1 is also involved in wound-induced JA biosynthesis (M. Afitlhile and D.F. Hildebrand, unpublished data). There are no reports as to whether other thiolase-encoding genes (e.g. PKT1 and PKT2) are involved in wounding- or defense-related JA biosynthesis. Our RNA gel-blot analysis shows that the abundance of PED1 transcripts is highly elevated in senescing leaves, whereas the mRNA of PKT1 and PKT2 is barely detectable throughout leaf development (Fig. 8), suggesting the involvement of PED1 in JA biosynthesis during leaf senescence.

In summary, our data support a role for JA in leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. This is based on the demonstration that exogenous application of JA induces leaf senescence, and this induction requires an intact JA signaling pathway. In addition, it was shown that the endogenous JA level in senescing leaves increased to nearly 500% of that in NS counterpart leaves, and this increase in JA level is apparently because of a subset of genes encoding isozymes for JA biosynthesis that are differentially activated during leaf senescence. The differential activation of these genes, especially the cytoplasmic LOX1, as discussed above indicates that the JA biosynthetic pathway in senescing leaves is mediated by different genes than those involved in the wounding and defense-related JA biosynthetic pathways involving the chloroplast-targeted LOX2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes, subject to the requisite permission from any third-party owners of all or parts of the material. Obtaining any permissions will be the responsibility of the requestor.

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The Arabidopsis mutant coi1 (Xie et al., 1998) was a gift from Dr. John G. Turner (John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK). The Arabidopsis ecotype Col-gl1 seeds were provided by Dr. Thomas Jack (Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH). Seeds were sterilized and grown in an Arabidopsis growth facility as previously described (He et al., 2001).

RNA Analysis

To minimize wounding- and dehydration-induced gene expression, leaf samples were quickly harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA extraction and northern-blot analysis were performed as described (He et al., 2001). RT-PCR was carried out by following the manufacturer's instruction (CLONTECH Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). The 18S rRNA primers and competimers of the QuantumRNA 18S Internal Standards Kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) were used as an internal standard. The competimers were specially modified primers that anneal to the 18S rRNA templates but could not be extended, resulting in the production of an attenuated 315-bp internal fragment. Products of RT-PCR were recovered from agarose gels by using the GENECLEAN III kit (BIO101, Vista, CA) and directly sequenced by using an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA). The primers used for RT-PCR analysis and for amplification of gene-specific probes of genes involved in JA biosynthesis are listed in Table II.

JA Treatments

For in planta treatment, germinated seedlings were grown on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog agar medium containing 30 μm JA (Sigma, St. Louis) for 12 d under 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle. JA treatment of detached leaves was performed as described (Xie et al., 2001). Detached young, NS rosette leaves were floated on 30 μm JA solution or water (control) for 4 d in the dark.

Quantification of JA and OPDA

JA and OPDA extraction and quantification were carried out according to a protocol modified from Albrecht et al. (1993). In brief, leaf material (about 1.0 g fresh weight) was collected from intact plants, quickly weighed, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen to minimize wound-induced JA accumulation. Samples were finely ground in a mortar while frozen. Dihydrojasmonic acid (a gift from Bedoukian Research Inc., Danbury, CT) was added to this sample at 0.2 nmol g fresh weight−1. Extracted samples were analyzed by GC-MS (GCD Plus, electron ionization mode, 30-m × 0.25-mm HP-5 column; Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA). The temperature gradient was 120°C for 1 min, 120°C to 270°C, at 6°C min−1. Quantification was by selective ion monitoring (measuring ions m/z = 224 for JA methyl ester, m/z = 226 for methyl dihydrojasmonate, and m/z = 306 for OPDA methyl ester).

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Measurements

Chlorophyll fluorescence in leaves was measured by using a portable modulated chlorophyll fluorometer (model OS1-FL, Opti-Sciences, Tyngsboro, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Fv and Fm of each leaf were directly quantified by using module 6 of the OS1-FL.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Richard Amasino (University of Wisconsin, Madison) and Drs. George Wagner and Arthur Hunt (University of Kentucky, Lexington) for stimulating and helpful discussion.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture-National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (grant nos. 2001–35304–09994 to S.G. and 9701487 to D.F.H.) and by the Tobacco and Health Research Institute's Biotechnology Program at the University of Kentucky (grants to S.G. and D.F.H.). Y.H. was supported in part by the University of Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund (Plant Sciences).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.010843.

LITERATURE CITED

- Albrecht T, Kehlen A, Stahl K, Knöfel H-D, Sembdner G, Weiler EW. Quantification of rapid, transient increases in jasmonic acid in wounded plants using a monoclonal antibody. Planta. 1993;191:86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bell E, Mullet JE. Characterization of an Arabidopsis lipoxygenase gene responsive to methyl jasmonate and wounding. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:1133–1137. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.4.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesgen C, Weiler EW. Structure and regulation of OPR1 and OPR2, two closely related genes encoding 12-oxophytodienoic acid-10,11-reductases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 1999;208:155–165. doi: 10.1007/s004250050545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleecker AB, Patterson SE. Last exit: senescence, abscission, and meristem arrest in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1169–1179. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V. The molecular biology of leaf senescence. J Exp Bot. 1997;48:181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Creelman R, Mullet J. Biosynthesis and action of jasmonates in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creelman RA, Mullet JE. Jasmonic acid distribution and action in plants: regulation during development and response to biotic and abiotic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4114–4119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S. Molecular characterization and genetic manipulation of plant senescence. PhD thesis. Madison: University of Wisconsin; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gan S, Amasino R. Making sense of senescence: molecular genetic regulation and manipulation of leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:313–319. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajouj T, Michelis R, Gepstein S. Cloning and characterization of a receptor-like protein kinase gene associated with senescence. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1305–1314. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms K, Atzorn R, Brash A, Kühn H, Wasternack C, Willmitzer L, Peña-Cortés H. Expression of a flax allene oxide synthase cDNA leads to increased endogenous jasmonic acid (JA) levels in transgenic potato plants but not to a corresponding activation of JA-responding genes. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1645–1654. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.10.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Toriyama K, Kondo M, Nishimura M. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxybutyric acid-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis have defects in glyoxysomal fatty acid beta-oxidation. Plant Cell. 1998;10:183–195. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Gan S. Identical promoter elements are involved in regulation of the OPR1gene by senescence and jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;47:595–603. doi: 10.1023/a:1012211011538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Tang W, Swain JD, Green AL, Jack TP, Gan S. Networking senescence-regulating pathways by using Arabidopsis enhancer trap lines. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:707–716. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand D, Afitlhile M, Fukushige H. Regulation of oxylipin synthesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:847–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand D, Fukushige H, Afitlhile M, Wang C. Lipoxygenases in plant development and senescence. In: Rowley A, Kuhn H, Schewe T, editors. Eicosanoids and Related Compounds in Plants and Animals. London: Portland Press Ltd.; 1998. pp. 151–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderhofer K, Zentgraf U. Identification of a transcription factor specifically expressed at the onset of leaf senescence. Planta. 2001;213:469–473. doi: 10.1007/s004250000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Yamada K, Hiraiwa N, Kondo M, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. Vacuolar processing enzyme is up-regulated in the lytic vacuoles of vegetative tissues during senescence and under various stressed conditions. Plant J. 1999;19:43–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudert D, Weiler EW. Allene oxide synthase: a major control point in Arabidopsis thalianaoctadecanoid signaling. Plant J. 1998;15:675–684. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig F, Sonnewald U. High CO2-mediated down-regulation of photosynthetic gene transcripts is caused by accelerated leaf senescence rather than sugar accumulation. FEBS Lett. 2000;479:19–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maucher H, Hause B, Feussner I, Ziegler J, Wasternack C. Allene oxide synthases of barley (Hordeum vulgarecv. Salome): tissue specific regulation in seedling development. Plant J. 2000;21:199–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melan MA, Dong X, Endara ME, Davis KR, Ausubel FM, Peterman TK. An Arabidopsis thaliana lipoxygenase gene can be induced by pathogens, abscisic acid, and methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:441–450. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.2.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miersch O, Wasternack C. Octadecanoid and jasmonate signaling in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentumMill.) leaves: Endogenous jasmonates do not induce jasmonate biosynthesis. Biol Chem. 2000;381:715–722. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PJ, Thompson GA. Molecular responses to aphid feeding in Arabidopsis in relation to plant defense pathways. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1074–1085. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris K, MacKerness SA, Page T, John CF, Murphy AM, Carr JP, Buchanan-Wollaston V. Salicylic acid has a role in regulating gene expression during leaf senescence. Plant J. 2000;23:677–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Oh S, Kim Y, Woo H, Nam H. Differential expression of senescence-associated mRNAs during leaf senescence induced by different senescence-inducing factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:445–454. doi: 10.1023/a:1005958300951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthier B. Jasmonates: hormonal regulators or stress factors in leaf senescence? J Plant Growth Regul. 1990;9:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx IA, Eggermont K, Terras FR, Thomma BP, De Samblanx GW, Buchala A, Metraux JP, Manners JM, Broekaert WF. Pathogen-induced systemic activation of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis follows a salicylic acid-independent pathway. Plant Cell. 1996;8:2309–2323. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.12.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontier D, Gan S, Amasino RM, Roby D, Lam E. Markers for hypersensitive response and senescence show distinct patterns of expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;39:1243–1255. doi: 10.1023/a:1006133311402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirino BF, Noh YS, Himelblau E, Amasino RM. Molecular aspects of leaf senescence. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:278–282. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01655-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha PSC, Topping JF, Lindsey K. Promoter trapping in Arabidopsis: one T-DNA tag, three transcripts and two thiolase genes. J Exp Bot. 1996;47:ss24. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CA. The systemin signaling pathway: differential activation of plant defensive genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:112–121. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders PM, Lee P-Y, Biesgen C, Boone JD, Beals TP, Weilerb EW, Goldberg RB. The Arabidopsis DELAYED DEHISCENCE1gene encodes an enzyme in the jasmonic acid synthesis pathway. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1041–1062. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.7.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller F. Enzymes of the biosynthesis of octadecanoid-derived signaling molecules. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller F, Biesgen C, Mussig C, Altmann T, Weiler EW. 12-Oxophytodienoate reductase 3 (OPR3) is the isoenzyme involved in jasmonate biosynthesis. Planta. 2000;210:979–984. doi: 10.1007/s004250050706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk PM, Kazan K, Wilson I, Anderson JP, Richmond T, Somerville SC, Manners JM. Coordinated plant defense responses in Arabidopsis revealed by microarray analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11655–11660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siedow JN. Plant lipoxygenase: structure and function. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:145–188. [Google Scholar]

- Stintzi A, Browse J. The Arabidopsis male-sterile mutant, opr3, lacks the 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase required for jasmonate synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10625–10630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190264497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda J, Kato J. Identification of a senescence-promoting substance from wormwood (Artemisia absinthum L.) Plant Physiol. 1980;66:246–249. doi: 10.1104/pp.66.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vick B, Zimmerman D. Biosynthesis of jasmonic acid by several plant species. Plant Physiol. 1984;75:458–461. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.2.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan P, Shockey J, Lévesque CA, Cook RJ, Browse J. A role for jasmonate in pathogen defense of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7209–7214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Avdiushko S, Hildebrand DF. Overexpression of a cytoplasm-localized allene oxide synthase promotes the wound-induced accumulation of jasmonic acid in transgenic tobacco. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;40:783–793. doi: 10.1023/a:1006253927431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Zien CA, Afitlhile M, Welti R, Hildebrand DF, Wang X. Involvement of phospholipase D in wound-induced accumulation of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2237–2246. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver LM, Gan S, Quirino B, Amasino RM. A comparison of the expression patterns of several senescence-associated genes in response to stress and hormone treatment. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:455–469. doi: 10.1023/a:1005934428906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidhase R, Kramell H, Lehmann J, Liebisch H, Lerbs W, Parthier B. Methyl jasmonate-induced changes in the polypeptide pattern of senescing barley leaf segments. Plant Sci. 1987;51:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Woo H-R, Chung K-M, Park J-H, Oh S-A, Ahn T, Hong S-H, Jang S-K, Nam H-G. ORE9, an F-box protein that regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1779–1790. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie DX, Feys BF, James S, Nieto-Rostro M, Turner JG. COI1: an Arabidopsis gene required for jasmonate-regulated defense and fertility. Science. 1998;280:1091–1094. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M, He Y, Gan S. Bidirectionalization of polar promoters in plants. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:677–679. doi: 10.1038/90296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler J, Stenzel I, Hause B, Maucher H, Hamberg M, Grimm R, Ganal M, Wasternack C. Molecular cloning of allene oxide cyclase: the enzyme establishing the stereochemistry of octadecanoids and jasmonates. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19132–19138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]