Abstract

Water transport was examined in solution culture grown seedlings of aspen (Populus tremuloides) after short-term exposures of roots to exogenous ethylene. Ethylene significantly increased stomatal conductance, root hydraulic conductivity (Lp), and root oxygen uptake in hypoxic seedlings. Aerated roots that were exposed to ethylene also showed enhanced Lp. An ethylene action inhibitor, silver thiosulphate, significantly reversed the enhancement of Lp by ethylene. A short-term exposure of excised roots to ethylene significantly enhanced the root water flow (Qv), measured by pressurizing the roots at 0.3 MPa. The Qv values in ethylene-treated roots declined significantly when 50 μm HgCl2 was added to the root medium and this decline was reversed by the addition of 20 mm 2-mercaptoethanol. The results suggest that the response of Qv to ethylene involves mercury-sensitive water channels and that root-absorbed ethylene enhanced water permeation through roots, resulting in an increase in root water transport and stomatal opening in hypoxic seedlings.

Hypoxia, a condition of oxygen deficiency in plant roots, is the main consequence of flooding or waterlogging. Plants respond to hypoxia with reduced root permeability, closure of stomata, hypertrophy of lenticels, epinasty, formation of aerenchyma, and adventitious roots (Vartapetian and Jackson, 1997). Ethylene accumulation is often assumed to be the factor responsible for many of the responses observed in plants exposed to hypoxia (Mattoo and Suttle, 1991; Abeles et al., 1992). Hypoxia induces the formation in roots of the immediate precursor of ethylene, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid, which is transported in the xylem to the shoots and there rapidly oxidized to ethylene (Mattoo and Suttle, 1991). The synthesis of ethylene and the response of plants to ethylene differ among tissues and different plant species (Abeles et al., 1992), and can be affected by different internal and environmental factors (Sharp et al., 2000; Grichko and Glick, 2001).

The effects of ethylene on stomatal closure are not clear. Several studies on the effects of exogenous ethylene on stomatal movements demonstrated differential responses between the examined species (Taylor and Gunderson, 1986; Woodrow et al., 1988; Gunderson and Taylor, 1991; Abeles et al., 1992). Exogenous ethylene is known to increase membrane permeability in petal cells (Mayak et al., 1977; Borochov and Woodson, 1989); however, its impact on cell-to-cell water transport has not been thoroughly examined.

Water transport across intact higher plant cell membranes occurs predominantly through water channels (aquaporins; Chrispeels et al., 1997). Aquaporins are located in root cell membranes (Chrispeels and Maurel, 1994) at a high density (Johansson et al., 1998). In our previous work (Wan and Zwiazek, 1999, 2001; Kamaluddin and Zwiazek, 2001), we showed that the root water channels in aspen (Populus tremuloides) and Cornus stolonifera rapidly responded to changes in root metabolism. Phosphorylation of the aquaporins has been suggested to be the likely mechanism controlling water permeation through the cell membranes (Maurel, 1997; Johansson et al., 1998). There is evidence that plasma membrane aquaporin PM28A from spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves is a phosphoprotein and that its phosphorylation is carried out by a Ca2+-dependent membrane-bound protein kinase (Johansson et al., 1996).

Ethylene has been shown to induce very rapid and transient protein phosphorylation with the involvement of Ca2+-dependent specific protein kinases in the induction of pathogenesis related genes in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves (Raz and Fluhr, 1993), epicotyl shortening in peas (Pisum sativum; Berry et al., 1996), and in the accumulation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase transcript in pea plants (Kwak and Lee, 1997). The ethylene-induced phosphorylation in pea tissues (Berry et al., 1996; Kwak and Lee, 1997) and in mung bean (Vigna radiata) hypocotyls (Kim et al., 1997) was inhibited with the application of a protein kinase inhibitor, okadaic acid. Okadaic acid also inhibited the phosphorylation of aquaporin phosphoprotein PM28A in spinach leaves (Johansson et al., 1996). These reports suggest that, through its effect on protein phosphorylation, ethylene may be involved in the regulation of water channel activities.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of exogenous ethylene on root water transport in aspen seedlings. We studied the hypothesis that the exposure of roots to ethylene would increase the transport of water in physiologically depressed roots of hypoxic seedlings. We measured the root hydraulic conductivity (Lp), stomatal conductance (gs), and root respiration in hypoxic seedlings before and after exposing the roots to ethylene. To confirm the effect of ethylene, we used an ethylene action inhibitor, silver thiosulphate (STS), and determined its effect on Lp in ethylene-treated plants. To determine the extent to which mercury-sensitive water channels are involved in ethylene-induced water transport, we also examined the effect of mercuric chloride on pressure-induced root water flow (Qv) in ethylene-treated roots.

RESULTS

Morphology of Hypoxic and Aerated Seedlings

A decline in growth rates of hypoxic seedlings was noticeable and drooping of leaves and hypertrophy of lenticels were evident. Aerated seedlings did not show leaf drooping; however, some hypertrophy of lenticels was also observed.

Response of gs to Hypoxia and Exogenous Ethylene

Root hypoxia resulted in a decrease in gs over time (Fig. 1A). A significant decrease in gs was observed within 1 d of hypoxic treatment. The decline in gs continued to d 11 when it measured less than 25% of the rates recorded for control seedlings. The gs values of aerated seedlings remained at a similar level throughout the experimental period.

Figure 1.

Effects of hypoxia and ethylene applied to roots of hypoxic plants on gs (A), Lp (B), and root respiration (C). Each data point represents mean (n = 5) ± se. Ethylene was applied to hypoxic seedlings at 9 pm on d 10 and measurements were taken on d 11.

The hypoxic roots exposed to ethylene for 12 h, including an 8-h-dark period, showed over a 2-fold increase in gs (Fig. 1A). The gs values of hypoxic seedlings treated with ethylene remained significantly higher than those of hypoxic seedlings throughout the measurement period, although there was a gradual decline in gs, over time on d 11 in ethylene-treated hypoxic seedlings as well as in well-aerated seedlings. There was no significant change in gs in untreated hypoxic seedlings over time on d 11.

Lp in Response to Hypoxia and Ethylene

Lp significantly decreased in response to hypoxia (Fig. 1B). Similarly to gs, a significant decrease in Lp was found within 1 d of hypoxic treatment and further decline continued until d 5 (Fig. 1B). Lp of well-aerated seedlings remained little changed throughout the experimental period.

Ethylene applied to the hypoxic seedlings at the end of d 10 triggered a drastic increase in Lp. When measured 12 h after ethylene treatment, there was a 3-fold increase in Lp of hypoxic plants (Fig. 1B). Unlike gs, Lp did not change appreciably over the measurement period on d 11 in ethylene-treated hypoxic, untreated hypoxic, and aerated control seedlings.

Root Respiration in Response to Hypoxia and Ethylene

Root respiration significantly decreased as a result of hypoxia (Fig. 1C). After 3 d of hypoxic treatment, root respiration rates declined to about 50% of those measured in aerated seedlings (Fig. 1C).

Ethylene significantly enhanced root respiration in hypoxic seedlings (Fig. 1C). Within 12 h after the application of ethylene, respiration rates of hypoxic plants were at over 80% level of the respiration rates measured in well-aerated control roots (Fig. 1C). Both ethylene-treated hypoxic and untreated hypoxic seedlings showed some decline in respiration rates over time on d 11 (Fig. 1C).

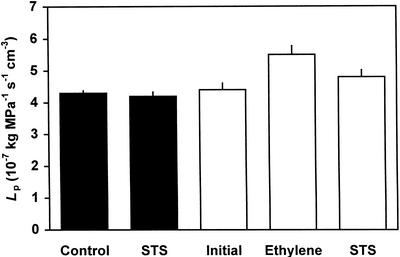

LP in Ethylene-Treated Plants Exposed to STS

Applied ethylene significantly increased LP in aerated seedlings (Fig. 2). Ethylene-treated aerated roots showed a 25% increase in LP compared with the values measured before ethylene treatment (P < 0.037). This increase in LP was observed within 15 min of pressurization. STS significantly reversed the enhancement of LP by ethylene (P < 0.044) when measured after 4 h of STS treatment. STS had no effect on LP of roots that had not been treated with ethylene (P < 0.524).

Figure 2.

Effects of STS on ethylene-enhanced Lp of aspen seedlings. Each data point represents mean (n = 7) ± se. The black bars indicate the control group and the white bars indicate the ethylene-treated group. The same root system of each group was measured after application of ethylene and/or STS.

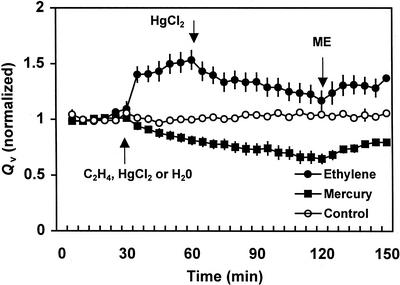

Mercurial Inhibition of Qv in Ethylene-Treated Roots

Pressure-induced Qv in ethylene-treated root systems increased by about 50% compared with the flow rate before treatment (Fig. 3). Qv in the untreated root systems remained constant throughout the measurement period (Fig. 3). Root systems treated with 50 μm HgCl2 showed a gradual decline in Qv. The decline commenced within 10 min after the addition of 50 μm HgCl2 and within 1.5 h, Qv decreased to about 65% of the pretreatment flow rates. A similar magnitude of decline in Qv was observed in ethylene-treated roots when HgCl2 was added to the bathing solution. In ethylene-treated roots, Qv decreased to about 66% of the ethylene-treated flow rate after adding 50 μm HgCl2 (Fig. 3). The inhibition in Qv by HgCl2 was partly reversed by the addition of 20 mm ME to the bathing solution. After the addition of ME, Qv increased to 80% of the pretreated flow rates in root systems not treated with ethylene within 30 min, and at the same time the recovery in ethylene-treated roots was 87% with the addition of ME.

Figure 3.

Effects of exogenous ethylene and mercuric chloride on Qv of aspen seedlings. Each data point indicates mean (n = 6) ± se. Arrows indicate the time of treatment with ethylene, mercuric chloride, 2-mercaptoethanol (ME), or water (control).

DISCUSSION

Root hypoxia brought about a substantial decrease in gs with a concomitant decline in Lp and root respiration in aspen seedlings (Fig. 1). Our data suggest that the reduction in Lp by hypoxia was likely because of the inhibition of water transport through the aquaporins. The presence of water channel proteins in the plasma membrane and the tonoplast allows a plant to regulate its water flow through the cell-to-cell pathway (Chrispeels et al., 1997). Metabolic dependence of Qv and the effects of respiration on water channel function have been reported for different plants (Tyerman et al., 1999; Wan and Zwiazek, 1999; Zhang and Tyerman, 1999; Kamaluddin and Zwiazek, 2001; Wan et al., 2001). In wheat (Triticum aestivum) root cells, the extent of inhibition of cell hydraulic conductivity was similar in roots treated with HgCl2 and hypoxia and interpreted as a result of the decreased phosphorylation of aquaporins (Zhang and Tyerman, 1999). NaN3, a potent inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation, is also known to rapidly inhibit Qv across membranes (Kamaluddin and Zwiazek, 2001). Water transport through some aquaporins is regulated by phosphorylation (Daniels et al., 1994; Maurel et al., 1995; Johansson et al., 1998). Stress-induced reduction in Lp can be caused by the decreased phosphorylation of aquaporins (Johansson et al., 1996, 1998). Therefore, it is conceivable that reduced phosphorylation of root cell aquaporins might be the cause of the decreased Lp that we observed in hypoxic seedlings.

In our study, ethylene applied to hypoxic seedlings enhanced gs with a concomitant increase in Lp and root respiration (Fig. 1). Although we did not examine the effects of ethylene on the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation of water channel proteins in this study, it is plausible that these events could be involved in this response. Under the condition of oxygen deprivation, the amount of ATP produced in the plant roots decreases (Reid et al., 1985). The decrease in Lp might be partly because of the inhibitory effects of hypoxia mediated through the decreased root respiration rates. There was a simultaneous decline in gs as a result of hypoxia (Fig. 1A). In a previous study (Wan and Zwiazek, 1999), we demonstrated that mercury-sensitive processes in roots were responsible for triggering stomatal closure in aspen leaves. It is plausible that similar processes were responsible for stomatal closure in hypoxic plants.

The role of abscisic acid (ABA) in the observed responses of plants to ethylene cannot be discounted. Ethylene has been reported to trigger ABA synthesis (Abeles et al., 1992; Hansen and Grossmann, 2000) and ABA triggers stomatal closure in stressed plants (Zeevaart and Creelman, 1988). Both ABA and gibberellic acid are also known to activate the promoter of the aquaporin PIP1b (Kaldenhoff et al., 1993, 1996) and some studies reported an increase in Lp of ABA-treated roots (Ludewig et al., 1988; Freundl et al., 1998; Hose et al., 2000), possibly by its effect on aquaporins (Abe et al., 1997; Hose et al., 2000). On the other hand, Wan and Zwiazek (2001) demonstrated that ABA applied to roots of hydroponically grown aspen seedlings reduced gs but not root Lp and other studies showed that ABA biosynthesis and transport to shoots is restricted under the oxygen shortage conditions (Zeevaart et al., 1989; Else et al., 1995). Therefore, ABA may not be the primary factor triggering changes in stomatal opening and Lp of hypoxic plants.

The effect of ethylene on phosphorylation of aquaporin proteins is yet to be investigated. There is, however, evidence that ethylene induces a rapid and transient protein phosphorylation in tobacco leaves, and a protein kinase inhibitor, H-7,1-(5-isoquinolinylsulfonyl)-2-methylpiperazine, blocked ethylene-induced pathogenesis-related protein accumulation (Raz and Fluhr, 1993). A rapid change in the pattern of protein phosphorylation was also induced by ethylene in pea epicotyls (Berry et al., 1996) and H-7-sensitive protein kinase(s) was found to be involved in ethylene-induced protein phosphorylation in pea seedlings (Kwak and Lee, 1997). In aerated roots, ethylene increased Lp within 15 min (Fig. 2), similar to the phosphorylation effect observed in tobacco leaves (Raz and Fluhr, 1993). The ethylene-induced increase in Lp of aspen was significantly reversed by the application of STS, which strongly and noncompetitively binds ethylene (Beyer, 1976). Because no changes in Lp were observed in control plants, STS action was likely due to its antagonistic action on ethylene binding. The anionic complex of STS is rapidly transported through plant tissues (Veen, 1983) and can negate the effects of ethylene even after short treatment (Reid et al., 1980). STS inhibited the ethylene binding in carnations (Sisler et al., 1986) and reversed the effects of applied ethylene on root extension growth in lettuce (Lactuca sativa; Abeles and Wydoski, 1987) and on seedling growth of barley (Hordeum vulgare; Locke et al., 2000). In our study, the application of ethylene resulted in an increase in Qv (Fig. 3) similar to the increase in Lp (Fig. 2). This increase in Qv in response to ethylene, the decline of the ethylene-induced Qv by HgCl2, and the substantial reversion by ME suggest the possible involvement of ethylene in mercury-sensitive processes, particularly the water channel activity, in the enhancement of Qv by ethylene.

In addition to increased Qv, both root respiration and gs increased in hypoxic seedlings after ethylene treatment (Fig. 1C). Respiration rates have been reported to increase in response to ethylene treatment in fruits (Frenkel et al., 1968; McGlasson et al., 1971) and roots (Kahl and Laties, 1989). Ethylene can enhance respiration via the alternative respiration pathways (Esashi et al., 1987) and increase tissue ATP content through mobilization of AMP or ADP (Perl, 1982). It is possible that similar mechanisms and the resulting effect on phosphorylation could also be partly responsible for the increase of Qv in our experiment. Phosphorylation-induced enhancement of the activity of root water channels could result in an increase in Qv rates, increase in leaf hydration, and stomatal opening. However, in our study, plants were removed from hypoxic mineral solution with dissolved oxygen levels of <2 mg L−1 and root respiration rates were measured under the oxygen levels of approximately 4 mg L−1 of the nonaerated Hoagland solution. Therefore, the measurements reflected respiration potential under somewhat elevated level of dissolved oxygen rather than the respiration under the prevailing oxygen levels of the hypoxic conditions.

In our study, hypoxic seedlings treated with ethylene for several hours showed a large increase in Lp, which was substantially higher than that observed in roots of aerated seedlings treated with ethylene for several minutes. This might be because of the pronounced responsiveness of the highly physiologically depressed hypoxic roots to ethylene rather than the difference in duration of ethylene treatment. The increased Lp (Fig. 2) and Qv (Fig. 3) as a result of short-term exposure of roots to ethylene adequately supported the water channel-mediated enhanced Lp in hypoxic seedlings. Because the duration of ethylene treatment for hypoxic seedlings was 12 h, the possibility that ethylene-induced root hair development (Taiz and Zeiger, 1998) could be the reason for the increase in Lp in hypoxic seedlings cannot be entirely ruled out. However, root hair development is often hampered in hydroponically grown plants (Fahn, 1982).

Although dissolved oxygen level of aerated solution was substantially greater than in nonaerated plants, aerated seedlings showed some signs of hypoxia by producing hypertrophic lenticels around the root collar region. In addition, the excised roots of aerated seedlings treated with ethylene in STS experiment and in Qv experiment were kept in stagnant bathing solution for about an hour before the treatment with ethylene and thus they likely experienced short-term hypoxic condition before ethylene treatment. This could explain why Lp or Qv of aerated seedlings also showed response to ethylene.

In summary, the results presented in this paper demonstrated an increase in Lp and gs of hypoxic aspen seedlings after exposing roots to ethylene. We suggest that root water channels likely mediated the ethylene-enhanced root water transport and we discuss the possibility of ethylene effects on phosphorylation of water channel proteins. We interpreted the response of gs to root-applied ethylene as a result of improved leaf hydration because of the enhancement of Qv.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Conditions and Hypoxic Treatment

Aspen (Populus tremuloides) seedlings were germinated and grown for 6 weeks in styrofoam containers filled with a peat:sand mixture (1:1, v/v) before transferring to aerated solution culture. The roots were gently washed free of soil in cold tap water and the seedlings were transferred to 10-L containers with one-half-strength modified Hoagland solution (Epstein, 1972). Ten containers, each with eight seedlings, were placed in a growth room set to a 16-h photoperiod with photosynthetic photon flux of 300 μmol m−2 s−1, 22°C/18°C (day/night) temperatures, and a constant relative humidity of approximately 70% (v/v). The seedlings were grown in solution culture for about 3 weeks before experimental treatments and the solution was replaced every 2 weeks.

The seedlings from five randomly picked containers were transferred individually into 0.5-L plastic containers containing one-half-strength Hoagland solution and hypoxia was induced by stopping aeration. The seedlings of other five containers were kept aerated and served as controls. During the hypoxic treatment, the whole root system and a part of the stem 1 cm above the root collar was always kept submerged in the solution. In the aerated containers, the concentration of dissolved oxygen in nutrient solution was always >7 mg L−1, whereas that in the nonaerated containers was <2 mg L−1.

gs Measurements

Leaf gs, was measured in hypoxic and control plants at 9 am on d 1, 3, 5, and 10 after the initiation of hypoxic treatment and at 3-h intervals on d 11 after adding ethylene to hypoxic plants. The measurements were carried out with a steady-state porometer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) in the same growth chamber where the seedlings were growing. The second fully developed leaf was measured for gs in each of the five seedlings per treatment (n = 5).

Lp Measurements

Root hydraulic conductance (Kr) was measured for excised root systems of seedlings. A high-pressure flow meter (HPFM; Dynamax Inc., Houston) was used for the measurements as described by Tyree et al. (1995). Each root system was subjected to a pressure increasing from 0 to 0.4 MPa. Kr was the slope of the regression line of the water flow over the applied pressure and expressed in kg MPa−1 s−1. Root volume of each root system was determined from the volume of displaced water and Lp was obtained by dividing the Kr value by root volume and expressed in kg MPa−1 s−1 cm−3 root volume. There were five root systems per treatment taken for all measurements (n = 5).

Root Respiration Measurements

Root respiration was measured as oxygen uptake using a Clark-type electrode (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Respiration rates were determined by placing the root system in an airtight cylinder containing nonaerated one-half-strength Hoagland solution with the initial oxygen level of approximately 4 mg L−1. The bathing solution was kept continuously stirred with a stirring bar during measurements. Oxygen uptake was monitored for 20 min by recording data every 5 min in five root systems per treatment (n = 5). Respiration rate was the average of oxygen uptake over time expressed in μg min−1 cm−3 root volume. Mean respiration rate recorded for control root systems was used to normalize the data for each root system of corresponding hypoxic seedlings.

Ethylene Treatment of Hypoxic Seedlings

The individual 0.5-L plastic containers containing hypoxic seedlings were exposed to ethylene at 21 h on d 10, just before the end of the day, 12 h before the measurements on d 11. The roots were sealed in the container with the lower two-thirds of the root system immersed in one-half-strength Hoagland solution and the upper one-third exposed to the air. Ethylene was supplied into the container from the ethylene gas cylinder through a narrow 1-mm diameter tube stretched up to the bottom of the container to a concentration of 20 μL L−1and then the tube was tightly closed. The concentration of the applied ethylene was determined by gas chromatography by comparing the peak area with that produced by pure ethylene standard. Air samples containing ethylene were injected into the 30-m-long, 0.32-mm internal diameter GS-Q column (J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA) and analyzed using a Hewlett-Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph (Hewlett-Packard, Mississauga, ON) under the following conditions: oven temperature, 60°C; injector and detector temperatures, 150°C; and carrier gas (helium) linear flow rate, 25 cm s−1.

The seedlings were placed in the growth chamber in the same growth chamber where the seedlings were growing. After 12 h, including an 8-h night period, gs, Lp, and root respiration were measured in ethylene-treated hypoxic, untreated hypoxic, and aerated seedlings (n = 5) on d 11 at 3-h intervals taking the first measurements at 9 am.

STS Treatment

An excised root system of aerated seedlings was used to record Kr with the HPFM. For ethylene treatment, the excised root system was placed in a plastic container with one-half of the container filled with one-half-strength Hoagland solution. Ethylene gas was supplied into the container following the same procedure as described above and the container was closed airtight. The container with the excised root system exposed to ethylene was then placed in a pressure chamber (PMS Instruments, Corvallis, OR) and pressurized at 0.3 MPa for 10 min. Fifteen minutes after pressurization, Kr of the ethylene-treated root systems was recorded with the HPFM. Then, STS in the form of 0.2 mm silver nitrate and 0.8 mm sodium thiosulphate, in 1:4 (w/v) molar concentration ratio (De Stigter, 1981), was added to the bathing solution and maintained at the room temperature for 4 h before measuring Kr of the root systems that had been exposed to ethylene. At the same time, the root systems that served as controls were also treated with STS and their Kr values were recorded before and after STS treatment as for the ethylene-treated roots.

Kr was measured in seven root systems (n = 7) of each treatment. Lp for individual root system was calculated from the Kr and root volume, and expressed in kg MPa−1 s−1 cm−3 root volume. Possible differences between treatment means were explored by paired Student's t test.

Measurements of Qv in Response to Ethylene and HgCl2

The steady-state root flow rate (Qv) was measured following the hydrostatic pressure method (Wan and Zwiazek, 1999; Kamaluddin and Zwiazek, 2001). A 0.25-L glass cuvette containing one-half-strength Hoagland solution was inserted into a pressure chamber (PMS Instruments). The solution was kept continuously stirred during the measurements with a magnetic stirrer. For the measurements, the stem was severed above the collar region and the roots sealed in the pressure chamber. The entire root system was immersed in the solution with the debarked part of the stem protruding through a rubber gasket secured to the lid of the pressure chamber. Chamber pressure was gradually increased to 0.3 MPa and held constant during the measurements. The protruding stem was fitted to a graduated pipette by a short piece of rubber tubing and the water expressed through the stem was collected into the pipette. Root Qv of the whole root system was monitored over time by recording the volume of sap every 5 min and the results were expressed in μL water min−1 root system−1.

Qv was measured in the root systems treated with ethylene and/or HgCl2. Qv of each root system was recorded for 30 min under constant pressure of 0.3 MPa before treatment. Then, the pressure was released and the roots were treated with ethylene or HgCl2. Ethylene treatment was given following the same procedure as described for the STS experiment. The ethylene-treated roots were then placed in the pressure chamber and the pressure of 0.3 MPa was restored. The flow was monitored for 30 min after the treatment with ethylene and then the ethylene-treated root system was treated with HgCl2. For HgCl2 treatment, the pressure was released and an appropriate amount of concentrated HgCl2 solution was injected into the bathing solution to achieve 50 μm concentration before pressurizing the roots again to 0.3 MPa. In this way, Qv of six root systems were monitored for another 1 h. For another set of six root systems, HgCl2 was added to the bathing solution after measurement of Qv over the initial 30 min and then monitored for another 1.5 h. Qv of the HgCl2-treated roots was measured for another 30 min after adding 20 mm ME to the bathing medium. Qv was also measured for six control root systems where HgCl2 or ME was replaced with distilled water and monitored over 2.5 h. Mean Qv value obtained over the initial 30 min was used to normalize the data for each root system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Mihaela Cristina Voicu for laboratory assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a research grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.010791.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abe H, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Urao T, Iwasaki T, Hosokawa D, Shinozaki K. Role of the Arabidopsis MYC and MYB homologs in drought- and abscisic acid-regulated gene expression. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1859–1868. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.10.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeles FB, Morgan PW, Saltveit ME., Jr . Ethylene in Plant Biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Abeles FB, Wydoski SG. Inhibitors of ethylene synthesis and action: a comparison of their activities in a lettuce root growth model system. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1987;112:122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Berry AW, Cowan DSC, Harpham NVJ, Hemsley RJ, Novikova GV, Smith AR, Hall MA. Studies on the possible role of protein phosphorylation in the transduction of the ethylene signal. Plant Growth Regul. 1996;18:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EM. A potent inhibitor of ethylene action in plants. Plant Physiol. 1976;58:268–271. doi: 10.1104/pp.58.3.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borochov A, Woodson WR. Physiology and biochemistry of flower of petal senescence. Hortic Rev. 1989;11:15–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels MJ, Daniels MJ, Weig A. Aquaporins and water transport across the tonoplast. Adv Bot Res. 1997;25:419–432. [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels MJ, Maurel C. Aquaporins: the molecular basis of facilitated water movement through living plant cells. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:9–13. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels MJ, Mirkov TE, Chrispeels MJ. The plasma membrane of Arbidopsis thaliana contains mercury-sensitive aquaporin that is a homolog of the tonoplast water channel protein TIP. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1325–1333. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stigter HCM. Ethephon effects in cut “sonia” roses after pretreatment with silver thiosulfate. Acta Hortic. 1981;113:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Else MA, Hall KC, Arnold GM, Davies WJ, Jackson MB. Export of abscisic acid, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid, phosphate and nitrate from roots of flooded tomato plants. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:377–384. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein E. Mineral Nutrition of Plants: Principles and Perspectives. London: John Wiley & Sons; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Esashi Y, Fuwa N, Kurota A, Oota H, Abe M. Interrelation between ethylene and carbon dioxide in relation to respiration and adenylate content in the pre-germination period of cocklebur seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 1987;28:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A. Plant Anatomy. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel C, Klein I, Dilley DR. Protein synthesis in relation to ripening in pome fruits. Plant Physiol. 1968;43:1146–1153. doi: 10.1104/pp.43.7.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freundl E, Steudle E, Hartung W. Water uptake by roots of maize and sunflower affects the radial transport of abscisic acid and the ABA concentration in xylem. Planta. 1998;207:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Grichko VP, Glick BR. Ethylene and flooding stress in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2001;39:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson CA, Taylor GE., Jr Ethylene directly inhibits foliar gas exchange in Glycine max. Plant Physiol. 1991;95:337–339. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.1.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, Grossmann K. Auxin-induced ethylene triggers abscisic acid biosynthesis and growth inhibition. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1437–1448. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.3.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hose E, Steudle E, Hartung W. Abscisic acid and hydraulic conductivity of maize roots: a study using cell- and root-pressure probes. Planta. 2000;211:874–882. doi: 10.1007/s004250000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I, Karisson M, Shukla VK, Chrispeels MJ, Larsson C, Kjellbom P. Water transport activity of the plasma membrane aquaporin PM28A is regulated by phosphorylation. The Plant Cell. 1998;10:451–459. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.3.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I, Larsson C, Ek B, Kjellbom P. The major integral proteins of spinach leaf plasma membranes are putative aquaporins and are phosphorylated in response to Ca2+ and apoplastic water potential. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1181–1191. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.7.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahl G, Laties GG. Ethylene-induced respiration in thin slices of carrot root. J Plant Physiol. 1989;134:496–503. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenhoff R, Kölling A, Richter G. A novel blue light- and abscisic acid-inducible gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encoding an intrinsic membrane protein. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:1187–1198. doi: 10.1007/BF00042352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenhoff R, Kölling A, Richter G. Regulation of the Arabidopsis thaliana aquaporin gene AthH2 (PIP1b) J Photochem Photobiol. 1996;36:351–354. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaluddin M, Zwiazek JJ. Metabolic inhibition of root water flow in red-osier dogwood (Cornus stolonifera) seedlings. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:739–745. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.357.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Kim WT, Kang BG, Yang SF. Induction of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase mRNA by ethylene in mung bean hypocotyls: involvement of both protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in ethylene signaling. Plant J. 1997;11:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S, Lee SH. The requirements of Ca2+, protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation for ethylene signal transduction in Pisum sativum L. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:1142–1149. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke JM, Bryce JH, Morris PC. Contrasting effects of ethylene perception and biosynthesis inhibitors on germination and seedling growth of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) J Exp Bot. 2000;51:1843–1849. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.352.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig M, Dörffling K, Seifert H. Abscisic acid and water transport in sunflowers. Planta. 1988;175:325–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00396337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo AK, Suttle JC. The Plant Hormone Ethylene. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C. Aquaporins and water permeability of plant membranes. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:399–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C, Kada RT, Guern J, Chrispeels MJ. Phosphorylation regulates the water channel activity of the seed specific aquaporin α-TIP. EMBO J. 1995;14:3028–3035. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayak S, Vaadia Y, Dilley DR. Regulation of senescence in carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) by ethylene, mode of action. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:591–593. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.4.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlasson WB, Palmer JK, Vendrell M, Brady CJ. Metabolic studies with banana fruit slices I changes in the incorporation of 14C-labeled compounds in response to cutting. Aust J Biol Sci. 1971;24:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Perl M. The effects of ethylene and temperature on ATP accumulation from various substances in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) seeds. J Exp Bot. 1982;33:456–462. [Google Scholar]

- Raz V, Fluhr R. Ethylene signal is transduced via protein phosphorylation events in plants. Plant Cell. 1993;5:523–530. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.5.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MS, Paul JL, Farhoomand MB, Kofranek AM, Staby GL. Pulse treatments with the silver thiosulfate complex extend the vase life of cut carnations. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1980;105:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Reid RJ, Dejaegere R, Pitman MG. Regulation of electrogenic pumping in barley by pH and ATP. J Exp Bot. 1985;36:535–549. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp RE, LeNoble ME, Else MA, Thorne ET, Gherardi F. Endogenous ABA maintains shoot growth in tomato independently of effects on plant water balance: evidence for an interaction with ethylene. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:1575–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Sisler EC, Reid MS, Yang SF. Effects of antagonists of ethylene action on binding of ethylene in cut carnation. Plant Growth Regul. 1986;4:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Taiz L, Zeiger E. Plant Physiology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GE, Jr, Gunderson CA. The response of foliar gas exchange to exogenously applied ethylene. Plant Physiol. 1986;82:653–657. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyerman SD, Bohnert HJ, Maurel C, Steudle E, Smith JAC. Plant aquaporins: their molecular biology, biophysics and significance for plant water relations. J Exp Bot. 1999;50:1055–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Tyree MT, Patino S, Bennink J, Alexander J. Dynamic measurements of root hydraulic conductance using a high-pressure flowmeter in the laboratory and field. J Exp Bot. 1995;46:83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Vartapetian BB, Jackson MB. Plant adaptations to anaerobic stress. Ann Bot. 1997;79:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Veen H. Silver thiosulphate: an experimental tool in plant science. Scientia Hortic. 1983;20:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wan X, Zwiazek JJ. Mercuric chloride effects on root water transport in aspen seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:939–946. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X, Zwiazek JJ. Root water flow and leaf stomatal conductance in aspen (Populus tremuloides) seedlings treated with abscisic acid. Planta. 2001;213:741–747. doi: 10.1007/s004250100547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X, Zwiazek JJ, Lieffers VJ, Landhäusser S. Effect of low temperature on root hydraulic conductance in aspen (Populus tremuloides) seedlings. Tree Physiol. 2001;21:691–696. doi: 10.1093/treephys/21.10.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow L, Thompson RG, Grodzinski B. Effects of ethylene on photosynthesis and partioning in tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. J Exp Bot. 1988;39:667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Zeevaart JAD, Creelman RA. Metabolism and physiology of abscisic acid. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1988;39:439–473. [Google Scholar]

- Zeevaart JAD, Heath TG, Gage DA. Evidence for a universal pathway of abscisic acid biosynthesis in higher plants from 18O incorporation patterns. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:1594–1601. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.4.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WH, Tyerman SD. Inhibition of water channels by HgCl2 in intact wheat root cells. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:849–857. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]