Abstract

Objectives. Botswana has one of the world’s highest HIV-prevalence rates and the world’s highest percentages of orphaned children among its population. We assessed the ability of income-earning households in Botswana to adequately care for orphans.

Methods. We used data from the Botswana Family Health Needs Study (2002), a sample of 1033 working adults with caregiving responsibilities who used public services, to assess whether households with orphan-care responsibilities encountered financial and other difficulties. Thirty-seven percent of respondents provided orphan care, usually to extended family members. We applied logistic regression models to determine the factors associated with experiencing problems related to orphan caregiving.

Results. Nearly half of working households with orphan-care responsibilities reported experiencing financial and other difficulties because of orphan care. Issues of concern included caring for multiple orphans, caring for sick adults and orphans simultaneously, receiving no assistance, and low income.

Conclusions. The orphan crisis is impoverishing even working households, where caregivers lack sufficient resources to provide basic needs. Neither the public sector nor communities provide adequate safety nets. International assistance is critical to build capacity within the social welfare infrastructure and to fund community-level activities that support households. Lessons from Botswana’s orphan crisis can provide valuable insights to policymakers throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

The AIDS pandemic is creating a generation of orphaned children who have lost 1 or both parents to the deadly disease. By 2004, an estimated 15 million children between the ages of 0 and 17 years had been orphaned by HIV/AIDS,1 and the rate of orphaning is increasing. Worldwide, the number of orphans increased by 23% between 2001 and 2003, although it would have declined in the absence of HIV.1

Almost 80% of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS, or 12.3 million infants and youth, are living in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Nearly 1 in 5 children in Zimbabwe and Lesotho, and 15% of children in Zambia, Swaziland, and Mozambique, require fostering and care.1 In Botswana, the nation with the highest rate of orphanhood (20%), an estimated 120000 children aged 0 to 17 years had lost their mother, father, or both parents to AIDS by the end of 2003.2 In addition, an estimated 200 000 children in Botswana will be orphaned by 2010.3

Twenty-five million people in sub-Saharan Africa are infected with HIV, and the orphan population is likely to expand as parents with HIV/AIDS continue to die. Botswana has the second-highest rate of HIV in the world.4 In 2003, 37% of adults aged 15 to 49 were HIV-positive,5 placing Botswana in danger of losing one third of its adult population by 2010.6 Although antiretroviral treatment is becoming more accessible in countries such as Botswana, Zambia, and South Africa, still only a portion of the people requiring treatment receives it.7 Even with declines in the rate of orphaning because of uptake in access to antiretroviral treatment, the orphan population in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to increase to 18 million children younger than 18 years by 2010.1

Historically, the fostering of children by extended family members, including aunts, uncles, grandparents, and other relatives, is common throughout sub-Saharan Africa.8 Extended family members have fostered children for a variety of reasons including the deaths of mothers in childbirth, for youth to gain access to education, and so that the children could be used for domestic labor.8 The tradition of fostering by extended family continues today and is a vital coping mechanism in nations with high HIV prevalence and growing orphan populations. Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 90% of orphaned children in households live with extended family members,9 and the working or income-earning households are considered to be in the best financial position to meet the costs of care, including providing basic needs such as food and shelter.

The advantages of extended-family fostering are that it is culturally acceptable and assumed to be sustainable throughout a child’s development, partially because communities will band together to support these households.8,10,11 In most cases, children can find stability, love, and emotional support in relatives’ homes.

By contrast, institutional care in orphanages or residential facilities is recommended only in desperate situations, such as when there is abuse, child-headed households without support, or homelessness.9,12 Institutional care generally lacks the capacity to meet emotional needs,9,13 costs more per child than family care, and is potentially unsustainable in the long term because of a reliance upon charitable giving.9,12

Consequently, fostering by extended-family households is the preferred choice guiding policy,1,14–18 even when it is unclear whether households are able to provide adequate care. In truth, the African tradition of strong extended-family networks sustaining households in times of need may no longer be viable.9,19 In some nations, urbanization has diminished the strength of extended-family networks and kinship obligations have become less compelling.20 Moreover, reports of breakdown in family ties have emerged when adults have expressed reluctance to care for orphans, fearing that additional children will be a drain on household finances.21 Subsequently, there are growing gaps for children to slip through in what were previously thought to be impermeable traditional extended-family networks.22

Furthermore, community members are commonly believed to provide the resources that sustain AIDS- and orphan-affected households.13,23 In reality, communities are often providing little or no support to individual households.10 In Botswana, rapid development has eroded the custom of reciprocity among community members.20 Families in Lesotho and Malawi reported that the burden of care lay with extended family households despite care policies stressing the role of communities.24 Community-based and nongovernmental organizations are also credited with supporting orphan households. However, one study from Uganda revealed that only 5% of orphans were reached by the combined efforts of nongovernmental organizations, government, and other donors, and community-based organizations reached only 0.4% of orphans.10

In 2004, 20% of sub-Saharan African households with children were caring for orphans,23,25 even though 2001 data shows that nearly 50% of households in the region were living on less than US $1 per day.26 Ample evidence confirms that households living in extreme poverty, such as those headed by nonworking and elderly grandparents, lack the resources to adequately care for orphans10 and that orphan care provided by destitute families can be disastrous for all concerned.17,27,28 Therefore, given that large-scale institutional care is impractical, impoverished households provide inadequate care, and communities and organizations lend minimal assistance, it would appear that economically productive, working households represent the greatest hope for providing adequate orphan care. Still, the feasibility of working households providing care and economically surviving over time is unclear. Nonetheless, there is a paucity of scientific research describing the impact of fostering on households.

Several existing studies examining orphan households have used snowball sampling and small sample sizes, which frequently capture the poorest of households.29,30 Analyses of national household surveys have provided insight into aspects of orphan care, yet these data sources may underrepresent working households where 1 or more adults are in the workplace during daytime hours when surveys are administered.23 In addition, much of the existing literature is based on data from the early- to mid-1990s, which may not be relevant given the rapid rate of HIV transmission and orphaning.30,31 In this study, working households are defined as those in which at least 1 adult had both working and caregiving responsibilities in the previous year.

Human and social development throughout sub-Saharan Africa is contingent upon the ability of working households to survive economically while caring for orphans. The purpose of this study is to assess whether, in light of current realities and policies, working households can adequately care for orphans without becoming impoverished. We examined whether working households encountered problems and whether they received assistance with orphan care.

METHODS

The Botswana Family Health Needs Study was conducted in 2002. A questionnaire was administered to adults waiting for services at government outpatient health centers in Gaborone, a major city; Molepolole, an urban village; and Lobatse, a small town. The number of surveys administered at each site was based on population estimates from the 2001 census.32 The sample was designed to reflect Botswana’s population distribution, where 40% live in cities, 44% live in urban villages, and 16% live in small towns. Adults who were aged at least 18 years, worked in the past year, and had caregiving responsibilities were included in the study.

Respondents were recruited at general, maternal and child health, and pediatric outpatient clinics in government hospitals. Many of the participants were seeking routine services for themselves or dependents, rather than treatment for an illness. Respondents were asked to list all household members, the vital status of each child’s parents, where each child’s surviving parents lived, and the reason for each child living away from the home, if applicable. Data were collected on income, housing characteristics, and problems caring for orphans and adults. Respondents were also asked if they received any financial or material support from other household members, relatives, community volunteers, or the government to assist with orphan care.

The overall response rate for the Botswana Family Health Needs Study was 96% resulting in 1033 surveys. Children aged 0 to 17 years who had reportedly survived their mother or their father, or both parents, were categorized as orphans. Orphan households were those where working adults provided care for at least 1 child whose parent had died. Of the 1033 working households surveyed, 379 or 37% were providing orphan care and these comprised the final sample for this study.

Household problems because of orphan caregiving were modeled with 2 outcomes. The first outcome was reported financial difficulties because of orphan care. The second outcome was a combined measure of 3 reported difficulties because of orphan care: financial difficulties, household shortages in basic needs, or trouble meeting household and community responsibilities, such as housework or other caregiving. This outcome serves as a combined measure of orphan-related financial, resource, and time restraints that might negatively affect the health and well-being of other household family members or the respondent.

The relation between reporting difficulties because of orphan care and key household characteristics was estimated in logistic regression models. The models were built stepwise and covariates were added if parameter estimates were significant at P < .05 in bivariate models. Differences in the −2 log likelihood statistic between models were calculated and the resulting χ2 statistics were used to determine the best model. The functional form of each model was checked graphically and was found to have met the assumption of linearity in the log odds. Data were analyzed using SAS Statistical Software, Version 8.02 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Working, Orphan Household Characteristics

Eighty percent of respondents in the Botswana Family Health Needs Study were female, which is not surprising given that women may be more likely than men to accompany their dependents when seeking health services. Forty percent of respondents were living with a spouse or partner, whereas 60% were single, separated, divorced, or widowed. The mean age of respondents was 35 years.

Of the 379 working households providing orphan care, 50% had electricity and 78% had running water, and 64% of household heads had completed secondary school or higher. Mean monthly household income was 1981 pula (US $396).

The mean household size was 5.84 persons and households ranged from caring for 1 to 9 orphans, with 54% caring for 1, 29% caring for 2, and 17% caring for 3 or more orphans. Extended family members provided the vast majority of orphan care. Fifty-nine percent of households reported caring for nieces and nephews, 28% cared for another relative, 6% cared for siblings, 5% cared for grandchildren, and 7% cared for a friend, neighbor, or had some other relationship to the orphan.

In many households, caregivers had additional responsibilities beyond providing orphan care and working. Forty-one percent also cared for sick adults and 45% cared for someone who had died in the past 5 years.

Caregiving Assistance

Only 2% of households reported receiving assistance from friends or neighbors and less than 1% reported receiving any type of support from community volunteers. Orphan households typically received support from other household members (43%), from relatives (39%), or from the government (34%). However, 15% of households received no assistance.

Problems Because of Caregiving

Forty-seven percent of working households reported financial difficulties because of orphan care and 48% reported financial problems; trouble providing food, shelter, or transportation; or difficulties meeting household and community responsibilities.

Logistic regression models illustrate the relation between household problems and the caregiving burden, income, and assistance (Table 1 ▶). Working households receiving no outside help were more than 3 times as likely to report financial difficulties as households receiving assistance. Households with high caregiving burdens, such as those caring for 3 or more orphans, were more than twice as likely to report financial difficulties as households that cared for a single orphan. The burden of caring for someone who met the clinical diagnosis for AIDS also showed a strong association with household difficulties, making these households nearly twice as likely to have problems. As expected, higher income reduced the likelihood of reported difficulties.

TABLE 1—

Logistic Regression Analyses of the Fitted Relationship Between Reporting Financial and Other Problems From Orphan Care, Household Characteristics, and Receiving Assistance (n = 376): Botswana, 2002

| Model 1: Financial Difficulties, OR (95% CI) | Model 2: Any Problems Because of Caring for Orphans,a OR (95% CI) | |

| Income | ||

| 0–1000 pula | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1001–2000 pula | 0.71 (0.42, 1.22) | 0.73** (0.42, 1.25) |

| 2001–13 500 pula | 0.31** (0.18, 0.55) | 0.31 (0.17, 0.54) |

| Number of orphans cared for | ||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.20 (0.72, 1.97) | 1.19 (0.72, 1.97) |

| ≥ 3 | 2.02* (1.10, 3.68) | 2.09* (1.14, 3.82) |

| Caring for adults and orphan assistance | ||

| Caring for adult who meets the World Health Organization clinical definition for AIDS | 1.95* (1.14, 3.34) | 1.98* (1.15, 3.41) |

| No orphan assistance provided | 3.34** (1.75, 6.36) | 3.54** (1.84, 6.83) |

| Model diagnostics | ||

| −2 log likelihood | 476.71 | 475.23 |

| −2 log likelihood from null model | 519.71 | 520.57 |

| C index | 0.68 | 0.69 |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

aCombined measure of 3 reported difficulties because of orphan care: financial difficulties, household shortages in basic needs, or trouble meeting household and community responsibilities, such as housework or other caregiving.

*P < .05; **P < .001.

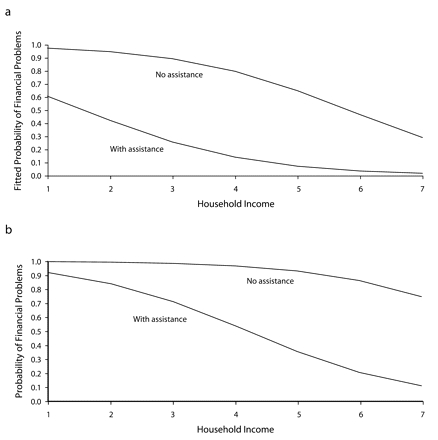

Figure 1a ▶ displays the fitted probability of having financial difficulties in households caring for 2 orphans and an adult with AIDS, at each level of income, depending on whether assistance was received. These households are bearing overwhelming care-giving responsibilities, and the lower-income households are nearly guaranteed to have problems in the absence of outside assistance. In working households with average monthly incomes of 1500 to 2000 pula, the probability of having financial difficulties drops from about 97% to 54% with orphan assistance. The fitted probability of having financial difficulties in households that care for 2 orphans and no adults is about 75% in households with average incomes, but drops to about 14% when assistance is provided (Figure 1b ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Fitted probability that a household will have financial difficulties because of orphan care based on income level and receiving orphan assistance in households not caring (a) and caring (b) for adults.

Figure 2a ▶ displays the fitted probability that a household that receives orphan assistance will experience problems at low, middle, and high levels of income depending on the number of orphans cared for in the home. Low-income households (monthly income < 1000 pula) are 62% more likely to face problems when they care for more than 1 orphan, whereas middle- (1001 to 2000 pula) and high- (> 2000 pula) income families are able to care for 2 and 4 orphans, respectively, before being more than 50% likely to have problems. The probability of experiencing problems in working households that do not receive orphan assistance is illustrated in Figure 2b ▶. Low- and middle-income households will assuredly experience problems without orphan assistance when caring for even a single orphan.

FIGURE 2—

Fitted probability that a household will have financial difficulties because of orphan care based on the number of orphans cared for in low-, middle-, and high-income households with assistance (a) and without assistance (b).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis demonstrates that even Botswana’s working households are struggling with orphan caregiving responsibilities and that low- and middle-income households lack the resources to provide basic needs. However, households receiving financial or material assistance have a greatly reduced probability of experiencing difficulties because of orphan care. Thus, extended-family caregiving may be sustainable with the support of an adequate public-sector safety net.

Regrettably, though, Botswana’s public sector lacks system capacity to fulfill existing duties as well as to respond to new AIDS- and orphan-related demands because of severely limited resources and inadequately developed infrastructure.33 The limited capacity of Botswana’s Social Welfare Division diminishes the effectiveness of the National Orphan Care Programme. Although an estimated 120 000 children are orphaned in Botswana, the Social Welfare Division had registered only 47 725 by March 2005 (Program Coordinator, Orphans and Vulnerable Children, Social Welfare Division, oral communication, March 2005). This large discrepancy is important because registration is a precursor to the receipt of public-sector material and financial support. Additional problems are surfacing as well. In 2005, only 42 social workers were responsible for care of more than 100 000 orphans in the 15 districts of Botswana (Program Coordinator, Orphans and Vulnerable Children, Social Welfare Division, oral communication, February 2005). According to department officials, capacity is far exceeded, retention is low, frustration is high, and the number of orphans is growing.

In the fiscal year 2003/2004, the government of Botswana spent an estimated US $50 million on activities related to the HIV/AIDS epidemic,34 but orphan care accounted for a mere 2% of the budget. Orphan care must compete with other priorities, including the scaling up of antiretroviral treatment distribution. Subsequently, the portion of resources allotted to orphan care is not commensurate with the costs of meeting the needs of orphans and caregiving households. Botswana’s District and Village Multisectoral AIDS Committees have proposed community-level interventions, including income-generating projects, support centers, and activities aimed at improving orphan registration. However, there is a desperate lack of funding for these activities despite the fact that they are frequently touted as the “orphan response.”

Our study captured a broad sector of households that use public services, thus including working households that might not be proportionally represented in home-based surveys administered during working hours. Though this study is building upon previous qualitative research, a limitation of this clinic-based sample is that findings can only be generalized to others in a position to use public services, rather than the entire population.

Additionally, the cross-sectional study design did not allow us to measure changes that occurred in caregiving households over time. Furthermore, we did not collect expenditure data or other information that would permit us to describe the actual mechanisms that result in household problems. This is a limitation in our study as well as in the national household surveys, which provide much of the data used in other research on orphan households. For example, do households become impoverished because caregiving duties reduce employment options or simply because orphan-related expenses exceed resources? Future studies should collect income and expenditure data, along with other theory-driven explanatory variables that help explain the mechanisms by which orphan care affects households. Longitudinal studies are essential if policymakers are to understand how orphan caregiving affects households through different stages of fostering.

These data were collected in 2002. At that time, many households lacked the capacity to provide basic needs. Since then, the social and economic crisis caused by HIV/AIDS has worsened as more households have lost family members to AIDS and have begun caring for orphans. If current trends continue, the number of orphans requiring care will surpass the material ability of households with limited resources to absorb children, regardless of their willingness.10,15

Furthermore, when households lose food security30 and sink into debt,10 children may lose access to health services and schools,23,35,36 enter the labor force,23 trade sex for money, and suffer from malnutrition and psychological distress.37 The long-term negative consequences of these impacts is immeasurable. Child welfare deteriorates in households where orphanhood is compounded by poverty.11,38 The high percentage of financially destabilized households identified in this study can potentially tip Botswana’s economic and social stability with implications for years to come.

The findings from the Botswana Family Health Needs Study have implications for households in all high HIV-prevalence countries, particularly those where the number of orphans has overwhelmed traditional support networks. Botswana has a history of good governance and investments in health and social welfare,7 and yet the public sector is unable to provide an adequate safety net. Furthermore, Botswana has 2 to 4 times the per capita gross domestic product of other nations with high orphan rates in sub-Saharan Africa (US $9200 in Botswana vs US $3200 in Lesotho, US $5200 in Swaziland, US $900 in Zambia, and US $1900 in Zimbabwe, in 2004).26 The prospects for southern Africa are of tremendous concern when, even in Botswana, working households are unable to provide adequate care and the public sector is unable to offer sufficient support.

Results from this study demonstrate that an immediate allocation of funds from the international community is necessary to improve public sector safety nets so that households can adequately care for orphans. Action is crucial to prevent growing orphan-based disparities in health and education, the financial collapse of households, the unraveling of communities, and, within several generations, the descent of national economies, and the emergence of failed states.

The world community recognizes that the orphan crisis has the potential to cause vast reversals in human and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa, where already one third of children do not finish primary school, 40% of adults are illiterate, and 1 in 6 children dies before reaching age 5.39 In 2001, the United Nations General Assembly Special Session Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS set specific targets for all participating nations, including, “ . . . implement national policies and strategies to build and strengthen governmental, family and community capacities to provide a supportive environment for orphans . . . affected by HIV/AIDS.”40 In June 2005, at the summit in Gleneagles, Scotland, Group of Eight nations acknowledged the crisis and declared their commitment to support all children orphaned and left vulnerable by AIDS.41 The Group of Eight leaders pledged to increase official development assistance for Africa by US$25 billion per year by 2010,41 with a portion of these resources directed at improving the situation of orphans by increasing home support and cash transfers. Although these resources would be divided among governance, economic, and human development goals, if truly delivered, they would have great potential for improving public services that can support orphan households.

Furthermore, at the United Nations World Summit in New York City in September 2005, the world community agreed to “[e]nsure that the resources needed for prevention, treatment, care and support . . . in particular [for] orphan children . . . are universally provided . . . ”42 Although previous international assistance has included some contributions and technical support, the international community’s response to the orphan crisis has been sorely limited, with efforts largely entailing unheeded calls for action.35 The degree to which these and other funding requests—such as The Africa Commission’s call for US$2 billion per year to meet orphans’ material and psychosocial needs43—are heeded will have an enormous impact on the health and development of a generation of children and the households that care for them.

The weight of orphan responsibilities is destabilizing working households in sub-Saharan Africa, and in Botswana in particular, where one third of the population may die within 8 to 12 years. Even in Botswana, where there is a strong policy framework, gaps in the social welfare infrastructure leave orphan households lacking basic needs and nearly impoverished. Social welfare infrastructures require immediate capacity building, management training, additional staff, and increased budgets to provide the safety net that stabilizes households.

Caregivers, community-based organizations, the public sector, and international partners must collaborate in implementing long-term solutions. A combination of funding and technical assistance is required to strengthen public-sector infrastructure and ultimately support orphan households. In addition, community-level responses must be supported, funded, evaluated, and replicated when successful.

Supporting orphan households is critical to the future of sub-Saharan Africa and urgent action is essential. Both national and international responses must be proportional to the gravity of the situation. With a long-standing commitment to policies promoting human development and economic growth, Botswana is poised to be a leader in developing and sustaining a viable orphan response, but desperately needs technical and financial resources to overcome substantial obstacles.

Acknowledgments

S.V. Subramanian is supported by the National Institutes of Health Career Development Award (1 K25 HL081275).

Our warm thanks to members of the research and administration teams at the Botswana–Harvard School of Public Health AIDS Initiative Partnership in Botswana and the Project on Global Working Families at the Harvard School of Public Health who facilitated and contributed to this study. We are particularly grateful to our diligent and conscientious data collection team; to the Mashi study teams in Lobatse, Mochudi and Molepolole; to Ria Madison for administrative support; to Karen Bogan for assistance with data management and programming; and to the staff of the clinics where we conducted interviews.

We are most indebted to those who took the time to participate in the study.

Human Participant Protection The Human Subjects Committee at the Harvard School of Public Health deemed the Botswana Family Health Needs Study exempt because of its confidential and anonymous nature.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors C. M. Miller conceptualized the research questions, conducted the data analysis, interpreted results, and wrote and revised the article. D. Rajaraman helped to draft the survey instrument and managed the data collection. S. Gruskin helped to conceptualize ideas and interpret findings, and reviewed drafts. S. V. Subramanian contributed to data analysis. S. J. Heymann developed the survey instrument, oversaw the fielding of the survey, helped to conceptualize ideas and interpret results, and reveiwed drafts.

References

- 1.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Children’s Fund, US Agency for International Development. Children on the Brink 2004: A Joint Report of New Orphan Estimates and a Framework for Action. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2004.

- 2.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund. Epidemiological Fact Sheets on HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infections: 2004 Update Botswana. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004.

- 3.MacFarlan M, Sgheri S. The Macroeconomic Impact of HIV/AIDS in Botswana. Working paper 01/80. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund; 2001.

- 4.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund. Epidemiological Fact Sheets on HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Infections: 2002 Update Botswana. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002.

- 5.Botswana 2003 Second Generation HIV/AIDS Surveillance. Gaborone, Botswana: The National AIDS Coordinating Agency; 2003.

- 6.Botswana Human Development Report 2000. Gaborone, Botswana: United Nations Development Programme; 2000.

- 7.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. AIDS Epidemic Update December 2004. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/wad2004/EPI_1204_pdf_en/EpiUpdate04_en.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2005.

- 8.Madhavan S. Fosterage patterns in the age of AIDS: continuity and change. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58: 1443–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Africa’s Orphaned Generations. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2003.

- 10.Deininger K, Garcia M, Subbarao K. AIDS-induced orphanhood as a systemic shock: magnitude, impact, and program interventions in Africa. World Dev. 2003; 31:1201–1220. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster G, Williamson J. A review of current literature on the impact of HIV/AIDS on children in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 3):S275–S284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subbarao K, Mattimore A, Plangemann K. Social Protection of Africa’s Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children. Washington, DC: The World Bank, Human Development Sector, Africa Region; 2001.

- 13.United Nations Children’s Fund, The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Children Orphaned by AIDS: Frontline Responses From Eastern and Southern Africa. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund; 1999.

- 14.Bhargava A, Bigombe B. Public policies and the orphans of AIDS in Africa. BMJ. 2003;326: 1387–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter SS. Orphans as a window on the AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa: initial results and implications of a study in Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31: 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muchiru S. The Rapid Assessment of the Situation of Orphans in Botswana. Gaborone, Botswana: Oakwood Management and Development Consultants, AIDS/STD Unit, Ministry of Health; 1998.

- 17.Smart R. Policies for Orphans and Vulnerable Children: A Framework for Moving Ahead. Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development, Futures Group International, Policy Project; 2003.

- 18.Social Welfare Division. Short Term Plan of Action on Care of Orphans in Botswana 1999–2001. Gaborone, Botswana: Ministry of Local Government; 1999.

- 19.Kamali A, Seeley JA, Nunn AJ, Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Ruberantwari A, Mulder DW. The orphan problem: experience of a sub-Saharan Africa rural population in the AIDS epidemic. AIDS Care. 1996;8:509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milligan A, Williams G. Botswana: Towards National Prosperity: Common Country Assessment 2001. Gaborone, Botswana: United Nations System in Botswana; 2001.

- 21.Botswana Ministry of Health, AIDS/STD Unit. The Rapid Assessment on the Situation of Orphans in Botswana. Gaborone, Botswana: Republic of Botswana; 1998.

- 22.Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. Extended family’s and women’s roles in safeguarding orphans’ education in AIDS-afflicted rural Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60: 2155–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monasch R, Boerma J. Orphanhood and childcare patterns in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. AIDS. 2004;18(suppl 2): S55–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ansell N, Young L. Enabling households to support successful migration of AIDS orphans in southern Africa. AIDS Care. 2004;16:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AIDS Education and Research Trust Web site. Available at: http://www.avert.org/aidsmoney.htm. Accessed March 12, 2005.

- 26.World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/data/wdi2005/pdfs/Table2_5.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2005.

- 27.Lewis S. UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on HIV/AIDS in Africa. Paper presented at: XIIIth International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa; September 21–26, 2003; Nairobi, Kenya.

- 28.Children in a World of AIDS. Westport, CT: Save the Children; 2001.

- 29.Situation Analysis on Orphans and Vulnerable Children. Gaborone, Botswana: United Nations Children’s Fund, Social Welfare Division; 2003.

- 30.Cross C. Sinking deeper down; HIV/AIDS as an economic shock to rural households. Soc Transition. 2001;32:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bicego G, Rutstein S, Johnson K. Dimensions of the emerging orphan crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1235–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Central Statistics Office. Population and Housing Census: Population of Towns, Villages and Associated Localities in August 2001. Gaborone, Botswana: Government of Botswana; 2001.

- 33.Simms C, Rowson M, Peattie S. The Bitterest Pill of All. The Collapse of Africa’s Health Systems. London, England: Save the Children; 2001.

- 34.National AIDS Coordinating Committee. Status of the 2002 National Response to the UNGASS Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. Gaborone, Botswana: Republic of Botswana, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Africa Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Partnership; 2003.

- 35.Miller CM. The Orphan Epidemic in Botswana. Boston, Mass: Society Human Development and Health, Harvard University; 2005.

- 36.Case A, Paxson C, Ableidinger J. Orphans in Africa: parental death, poverty, and school enrollment. Demography. 2004;41:483–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atwine B, Cantor-Graaea E, Bajunirwe F. Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urassa MB, Ng’weshemi JT, Isingo R, Schapink D, Kumogola Y. Orphanhood, child fostering and the AIDS epidemic in rural Tanzania. Health Transit Rev. 1997;7(suppl):141–153. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Human Development Report 2005. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2005. Available at http://hdr.undp.org/reports/global/2004/pdf/hdr04_HDI.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2005.

- 40.United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS. June 25–27, 2001. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/whatsnew/others/un_special/index.html. Accessed October 4, 2005.

- 41.Gleneagles Summit Documents: Signed Version of Gleneagles Communique on Africa, Climate Change, Energy and Sustainable Development: July 2005. Available at: http://www.fco.gov.uk/Files/kfile/PostG8_Gleneagles_Communique,0.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2005.

- 42.United Nations World Summit. High-level Plenary Meeting of the General Assembly 14–16 September 2005. Draft Outcome Document. Available at: http://www.un.org/ga/president/59/draft_outcome.htm. Accessed October 4, 2005.

- 43.Our Common Interest: Report of the Commission for Africa. London, England: Commission for Africa; 2005.