Abstract

Sustaining important public or grant-funded services after initial funding is terminated is a major public health challenge. We investigated whether tobacco treatment services previously funded within a statewide tobacco control initiative could be sustained after state funding was terminated abruptly. We found that 2 key strategies—redefining the scope of services being offered and creative use of resources—were factors that determined whether some community agencies were able to sustain services at a much higher level than others after funding was discontinued. Understanding these strategies and developing them at a time when program funding is not being threatened is likely to increase program sustainability.

PUBLIC FUNDS OFTEN support innovative public health policies and services at the community level, but many times these policies and services are not sustainable when funding is discontinued. Several models have been developed that identify sustainability factors important to funders and community agencies who are considering the long-term institutionalization and sustainability of a program’s services at that program’s inception.1–6 However, if planning efforts are to be better informed, models also are needed to understand the factors most critical to program sustainability at the time when funding is discontinued.

In the field of public health, sustainability has been defined as the capacity to maintain program services at a level that will provide ongoing prevention and treatment for a health problem7 after termination of major financial, managerial, and technical assistance from an external donor.8 An entire service may be continued under its original or an alternate organizational structure, parts of the service may be continued, or there may be a transfer of some or all services to local service providers. In contrast to the notions of institutionalization and routinization, “sustainability” does not imply either that a service continues within its original organizational structure or that no changes are made in the service.4

The Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program (MTCP) of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, launched in 1993, sought to change smoking policies at the community level, to motivate smokers to quit via a statewide media campaign, and to provide tobacco treatment services for smokers who wanted to quit,9 including community-based individual or group behavioral counseling combined with pharmacological treatment according to the guidelines published by the Public Health Service.10,11 The MTCP also funded “counseling-only” services via a statewide quit line.

The MTCP lost 90% of its funding in early to mid-2002 during a nationwide recession, and community-based tobacco treatment programs were defunded beginning in late summer 2002. Immediately after defunding occurred, investigators at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, including ourselves and others on a project team funded by the National Cancer Institute to investigate Massachusetts’ state and community tobacco control initiatives, sought answers to a pair of questions in an effort to explore factors associated with program sustainability: What strategies enhance sustainability of services after public funds have been discontinued, and what variations exist in the ability of organizations to sustain services?

STUDY DESIGN AND PROCEDURES

We used qualitative analyses of state- and community-level programs to investigate factors contributing to sustainability of services after defunding and to examine varying levels and patterns of sustainability. We examined 77 of the 86 (89.5%) agencies that had received tobacco treatment funding from MTCP and subsequently been defunded: 21 hospitals, 27 community health centers, 9 substance abuse treatment agencies, 6 mental health agencies, and 14 agencies falling in other categories. Of the 11 agencies not included in the sample, 10 declined to be interviewed and 1 had a conflict of interest. Half-hour interviews were conducted with 4 MTCP state-level informants. One informant directly involved in administering or delivering services at each of the 77 community-based programs assessed was interviewed 3 months and 9 months after defunding. We were unable to gather data over a longer time span because we were nearing completion of our 4-year grant funding.

We developed interview scripts that were designed to assess factors and strategies facilitating or inhibiting program sustainability and to determine the level of services being sustained. Staff from agencies other than the MTCP were interviewed via telephone; MTCP staff still employed at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health were interviewed in person, and those no longer employed at the department were interviewed by telephone.

All interviews were taped and transcribed for ease of analysis (as described by LaPelle12). After considering 3 types of qualitative data analysis—immersion/ crystallization, editing, and template13–15—we decided to use immersion/crystallization to identify themes derived from interview responses, after which we developed a theme codebook to guide the coding. This code-book defined each theme category, assigned a numerical code, and specified limitations on the text that should be coded with each theme code. Coding, sorting, and code validation procedures followed the guidelines described by LaPelle.12 Themes and related observations were summarized in modifiable data tables to allow comparisons across cases.16

We used a grounded theory technique,17,18 theoretical coding, to examine and code relationships between themes that emerged from the interviews. In the initial phase of theoretical coding, we used hierarchical thematic analysis; that is, we iteratively grouped thematically related subcategories into higher level categories.19 After hierarchical analysis reduced the possible strategy categories to 2 key categories, we used theoretical coding to identify causal relationships between these 2 interdependent strategies and sustainability.

ESSENTIAL SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGIES

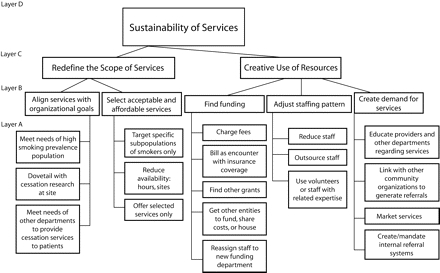

Thematic analyses and data coding resulted in a hierarchical grouping of strategies in layers, from A to D (Figure 1 ▶). At the most detailed layer, layer A, were a list of substrategies identified by informants from agencies that had been able to sustain services after defunding. These substrategies were collapsed to form layer B, which was composed of 5 more general strategies: (1) aligning services with organizational goals, (2) selecting acceptable and affordable services, (3) locating funding, (4) adjusting staffing patterns, and (5) assigning resources to create demand for services. Subsequent hierarchical grouping of theme codes resulted in 2 key strategies (layer C) for promoting sustainability (layer D): redefining the scope of services and engaging in creative use of resources.

FIGURE 1—

Essential strategies for sustainability after funding is discontinued.

Layer C strategies were found to have interdependent causal relationships with sustainability (layer D), suggesting that agencies that successfully sustained programs performed well in terms of both redefining the scope of the services they offered to align with their mission and their clients’ needs and engaging in creative use of resources to fund, staff, and create demand for services. We assessed community organizations in Massachusetts and the state-level MTCP in terms of their use of these strategies and the levels at which they were able to sustain programs after defunding.

Redefining Service Scope

Aligning services with organizational goals.

Programs that were able to sustain services after defunding served populations with high smoking prevalence rates. Their tobacco treatment services were aligned with their mission to address the health care needs of their target populations, and these treatment services had received strong organizational support in the past. Some of these programs based their decision to sustain services on their need to adhere to Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations requirements, offering tobacco treatment services as a supplement to inpatient treatment of pneumonia or cardiovascular disease. Others were instituting smoke-free workplaces and needed tobacco treatment support for staff members, and still others were conducting research related to tobacco treatment. The MTCP sustained statewide tobacco treatment services and supported other Massachusetts Department of Public Health divisions (e.g., cancer control and maternal and child health) by providing quit-line services.

Selecting acceptable or affordable services.

Some sustained programs provided services only to specific populations for which they could obtain targeted grant funding (e.g., Latinos, HIV/AIDS patients) or inpatient services for which insurance companies offered coverage. Others cut the number of site locations or hours of service, moved from offering individual sessions to offering group treatment, or eliminated free or subsidized nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Some agencies integrated tobacco treatment services with other outpatient services.

In partnership with 8 major health plans (both HMOs and the state Medicaid agency), the MTCP continued to develop its tobacco treatment service collaboration, QuitWorks, which embedded the statewide quit line services within a provider referral and quit line feedback framework promoted by the health plans.20 These quit line services were affordable, available to a large number of people statewide, provided in several languages, and modeled after evidence-based Public Health Service treatment guidelines.

Engaging in Creative Use of Resources

Locating funding.

Two thirds of programs that were able to sustain services after defunding charged fees for counseling, NRT (in relevant instances), or both. Some billed for tobacco treatment services in conjunction with other services (e.g., treatment for respiratory disease) for which insurance coverage was available. Sustained programs generally had staff who could effectively identify funding sources and apply for grants. In 3 cases, services and staff were transferred to a related group (e.g., a corporate education group or a community coalition) with available funding. At the state level, the QuitWorks collaboration with health plans was sustained with remaining MTCP funding.

Adjusting staffing patterns.

Many sustained programs retained at least one trained tobacco treatment specialist, establishing additional roles to help obtain funding for the position. In other cases, tobacco treatment specialists left programs, becoming external service providers to whom referrals were channeled. Some organizations began to offer tobacco treatment through another staff member such as a substance abuse counselor, social worker, psychology intern, or nurse educator. The MTCP shifted from a Massachusetts-only quit line to a telephone counseling service staffed by a national contractor.

Assigning resources to create demand for services.

Informants stressed how essential it was that clinicians be committed to making tobacco treatment referrals. Sustained programs often had institutionalized the referral system previously required by the MTCP and continued to inform providers about treatment services to generate internal referrals. In some agencies, other established programs such as hypnotherapy, diabetes management, and asthma management served as referral sources. Most informants also stressed the importance of engaging in community outreach to generate demand for services. At the state level, the QuitWorks collaboration created a systematic outreach, referral, and feedback process as health plans educated affiliated primary care physicians in using the system.

Levels of Sustainability

We used the ways in which redefining scope and engaging in creative use of resources can be combined to create 4 levels of sustainability (Table 1 ▶): (1) no sustainability, (2) low sustainability, (3) moderate sustainability, and (4) high sustainability. Table 1 ▶ also shows the percentage of agencies at each sustainability level. At level 1 (no sustainability), 25 agencies (33% of the originally funded programs) were able to sustain only external referrals for tobacco treatment services 9 months after defunding as a result of their commitment to other agency priorities.

TABLE 1—

Variation in Substrategies Among the Levels of Sustainability

| Substrategy | Level 1: No Sustainability | Level 2: Low Sustainability | Level 3: Moderate Sustainability | Level 4: High Sustainability |

| Redefining scope of services | ||||

| Alignment with organizational goals | Drop tobacco treatment— low priority | Serve high–smoking prevalence populations where possible | Gradually restore services available to all smokers and ethnic groups | Continue to provide services to all smokers |

| Selection of acceptable and affordable services only | Refer externally | Limited services for specific populations No NRT unless covered by insurance Integrate with other treatment services |

Provide only group services Provide all previous service except NRT Provide only phone- or Web-based services |

Continue to offer the same level of services as when funded |

| Creative use of resources | ||||

| Funding | Fees not acceptable to clients No grant-writing resources |

Limited grant-writing resources | Seek alternate funding sources for counseling and NRT | Use existing grant-writing resources to develop funding sources |

| Staffing | No staff to deliver services | TTS staff provide fewer sessions at fewer sites Services provided by interns, volunteers, and nonspecialists |

Use contract staff Share staff with other departments Transfer program to related groups with more resources |

Maintain required staff |

| Creating demand for services | No staff to create demand | No outreach Internal referral systems not optimized |

Emphasize use of internal referral system | Provide marketing and outreach support Encourage agency-wide internal referrals |

Note. NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; TTS = tobacco treatment services. Of the 77 originally funded agencies, 33% (25) operated at level 1, 34% (26) operated at level 2, 27% (21) operated at level 3, and 7% (5) operated at level 4.

Level 2 (low sustainability) included 26 agencies (34%) offering only minimal tobacco treatment services. These agencies provided services for less than 20% of their former number of clients. In addition to screening at intake, organizations often attempted to integrate brief tobacco treatment into other routine outpatient services covered by insurance providers. In other cases, services were offered only in the form of a single consultation after a regular visit. Many programs were able to sustain limited services to subpopulations such as patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, diabetes, and asthma. In other instances, services were available only to inpatients or day surgery patients. Generally, NRT was not offered unless it was covered in conjunction with inpatient services. These agencies did not have staff available to seek funding or market services. They tended to use volunteers, interns, or health care staff who were not trained tobacco treatment specialists but whose services were covered by insurance providers.

At level 3 (moderate sustainability), 21 agencies (27%) were able to identify partial funding sources and sustain some of the services they offered, after which they sought additional funding to expand the range of services available. These agencies were able to provide services at a level representing 20% to 50% of their former volume. In some instances, funding initially covered only services offered to uninsured individuals or members of certain ethnic or socioeconomic groups. Some agencies laid off staff but continued to use them on a fee-for-service basis. Many began charging fees for services, ranging from a low of $2 per session for smokers with MassHealth and Medicaid coverage to as much as $20 for group sessions, $27 for NRT sessions, and $50 for individual sessions. A few of these agencies had been awarded grants through which they could provide NRT at no charge. Most had effective referral systems in place.

Finally, at level 4 (high sustainability), 5 agencies (7%) did not narrow their scope of services and sustained these services at more than 50% of their former volume. One of these agencies provided group and individual services at no charge to clients, whereas 4 charged fees of $4 to $20 for counseling sessions. One provided NRT via grant funding to those unable to pay. The other agencies provided NRT for $5 to $18 per session. All 5 agencies laid off only minimal staff. Most had ongoing grant-writing capabilities and marketing mechanisms.

Table 2 ▶ shows the number of agencies of each type at each sustainability level as defined by the percentages of service volumes available before defunding that could be sustained at 3 months and 9 months after defunding (i.e., 0% for level 1, less than 20% for level 2, 20%–50% for level 3, more than 50% for level 4). At both of these intervals, approximately 67% of defunded agencies were able to sustain some level of programs or services. Overall, among agencies at the top 2 sustainability levels, slightly more were sustaining services after 9 months (34%) than after 3 months (31%). There was significant movement of individual agencies among sustainability levels during this 6-month time frame. Five agencies increased their sustainability level, and 7 agencies decreased their level.

TABLE 2—

Types of Defunded Agencies at Each Sustainability Level After 3 and 9 Months

| Level 1: No Sustainability, No. (%a) | Level 2: Low Sustainability, No. (%a) | Level 3: Moderate Sustainability, No. (%a) | Level 4: High Sustainability, No. (%a) | |||||

| Agency Type | 3 Months | 9 Months | 3 Months | 9 Months | 3 Months | 9 Months | 3 Months | 9 Months |

| Hospital (n = 21) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 9 (43) | 8 (38) | 5 (24) | 9 (43) | 6 (29) | 3 (14) |

| Community health center (n = 27) | 8 (30) | 8 (30) | 12 (44) | 12 (44) | 4 (15) | 6 (22) | 3 (11) | 1 (4) |

| Substance abuse treatment agency (n = 9) | 5 (56) | 5 (56) | 3 (33) | 3 (33) | 1 (11) | 1 (11) | 0 | 0 |

| Mental health treatment agency (n = 6) | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| Other (n = 14) | 10 (71) | 10 (71) | 1 (7) | 0 | 2 (14) | 3 (21) | 1 (7) | 1 (7) |

| Total (n = 77)b | 25 (34) | 25 (33) | 28 (36) | 26 (34) | 14 (18) | 21 (27) | 10 (13) | 5 (7) |

Note. See text for descriptions of levels.

aPercentage of agency type total.

bPercentages refer to total number of agencies.

At 9 months, 95% of hospitals, 70% of community health centers, 44% of substance abuse treatment centers, 83% of mental health centers, and 29% of other types of agencies were able to sustain services to at least some degree. Fifty-seven percent of hospitals, 26% of community health centers, 11% of substance abuse centers, 33% of mental health centers, and 29% of other types of agencies were able to sustain services above levels 1 and 2. At level 4, 14% of hospitals were able to sustain services, whereas no more than one agency in the other categories was still offering services.

Relation of Findings to Other Models

Other researchers have investigated sustainability or the closely related concept of institutionalization either of a single program or across many programs.1–6 Whereas institutionalization generally refers to programs that are continued without adaptation, sustainability includes possible adaptation of a program within or beyond an organization. Comparison of our model (Figure 1 ▶) with models outlined in previous research provides some insight into factors supporting institutionalization versus sustainability.

Goodman and Steckler developed an institutionalization model in a case study of 10 health promotion programs.3 Their model defined 6 factors associated with institutionalization: standard operating routines, conditions leading to perceived benefits over costs, mutual adaptation of stakeholders’ aims (e.g., those of administrators, program staff, and program clients) into program advocacy, actions of a program champion, mutual adaptation of program and organizational norms, and alignment of the organizational mission with core operations. All of Goodman and Steckler’s factors were observed in our target agencies, but one was not identified as a sustainability factor: the standard operating routines required by the MTCP provided a useful foundational system, but adaptation of operating routines was constant after defunding. Standard operating procedures were identified, rather, as a factor associated with success in the early phases of a program.

Bracht and colleagues investigated 9 factors related to institutionalization of programs associated with a heart health demonstration project after termination of federal funding.1 They defined success in this instance as a combination of 3 of these factors: first, a local service provider is operating the program; second, this local provider is operating the program in a modified form; and, third, the provider is operating the program but offering it intermittently. Modifications included redefining program scope to serve different target groups, instituting changes in content to broaden or narrow focus, repackaging programs to sustain their appeal, and dropping programs no longer aligned with the organization’s mission.

Bracht and colleagues found that the programs that had been discontinued had not attracted enough client demand or had not located alternative funding. In addition, their study informants reported that some of these discontinued programs were later reinstated or that new agencies picked them up. Their findings support our strategies of redefining scope and engaging in creative use of resources, and they also support an expanded definition of sustainability that entails more than simply institutionalization within a specific setting.

Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone developed a conceptual framework and operational definitions related to planning for sustainability.4 They suggested that potential influences stemmed from 3 major groups of factors: (1) project design and implementation, (2) organizational setting, and (3) broader community environment. In our study, organizational setting and broader community environment were important factors in fostering sustainability after defunding because internal referral systems integrated tobacco treatment with other agency services and community outreach created a demand for services. However, one of our major findings was that informants did not identify program design and staff capacity to deliver services as fostering sustainability. These factors were emphasized by the MTCP before defunding, and both contributed to the ability of agencies to implement programs successfully. After defunding, the scope of services was often adapted to a significant degree in sustained programs, and many capable tobacco treatment specialists were laid off.

Using a structured questionnaire based on the Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone model, Evashwick and Ory studied 20 organizations nationwide that had sustained innovative gerontological health care programs.2 They found that some programs focused on one successful component from the original service components available (our “selecting acceptable and affordable services” category). Over time, services were institutionalized within the existing funding system because they were perceived as part of the organization’s core values and mission (“aligning services with organizational goals” in our model). Evashwick and Ory found that financing was the greatest challenge to organizations, but creative ways were found to keep projects afloat, including use of volunteers and lean administrative staffs (our creative funding and staffing strategies). They also found that marketing and communication concepts were important in terms of continuation and expansion (our “creating a demand for services” category).

At the international level, the US Agency for International Development has proposed that organizational vision, local institutional support, institutional capacity, and demand for services are prerequisites for institutional sustainability. Furthermore, the agency has suggested that sustainability is improved when local organizations raise revenues through fees charged for products or services rather than being fully dependent on grants.6 These stipulations support our “align services with organizational goals” substrategy as well as the substrategies falling under creative use of resources.

Limitations

Because we examined 90% of the tobacco treatment programs that had previously been funded by the MTCP, our sample was highly representative. However, as mentioned, we were able to gather data only at 3 and 9 months after defunding because our grant funding was nearing completion. We are not able to predict whether some of the organizations that have been able to sustain services will continue to do so in the long term, nor can we foresee whether nonsustaining programs will be able to reinstitute services in the future. A longer term study is necessary to examine sustainability over time.

Another limitation of our study is that considerable variability exists in the scope of services offered at each agency and in the methods used in tracking these services. While funding was in place, specific units of service were tracked, and this information was reported to funders; after defunding, however, there was less incentive or administrative support for consistent tracking. Our reported percentages in terms of service volumes offered after defunding are best-guess estimates rather than actual values, and they may involve inaccuracies.

Implications and Conclusions

In relation to promoting sustainability after defunding occurs, one of our key findings was the importance of redefining the scope of services offered so that these services are the most acceptable and affordable options and fit best with an agency’s mission and the needs of at-risk clients. In addition, we found that engaging in creative use of resources and creating a demand for services are key factors in ensuring that the necessary resources are in place. Clearly, resourcing must be appropriate in terms of providing funding for staff if it is to create a demand for and provide the services included in the redefined scope.

Our study, with its focus on the factors most relevant at the time of defunding, reinforces findings from other investigations and contributes unique insights into program sustainability. Also, it highlights the need to understand effective sustainability strategies at the time of defunding in addition to program planning. Organizational contexts are also an important consideration at both points. We can infer, from the variations apparent in our results, that such contexts are associated with the likelihood of a program’s sustainability.

For example, hospitals were clearly in a better position to sustain services at higher levels than other types of agencies. Substance abuse treatment centers were least able to sustain services at high levels. Their mission had historically not included tobacco as an addiction, and tobacco cessation had not been seen as an aid to cessation of alcohol and other drug abuse. Community health and mental health centers and other types of community service agencies were better able to align tobacco treatment with their agency missions than substance abuse centers but did not have the necessary resources to sustain services as well as did hospitals. The resulting public health implication is that funding more hospitals may increase sustainability but may not guarantee that the individuals most at risk will receive treatment.

In addition, we found that some of the factors identified in other studies as sustainability factors, such as program design, capacity building, and administrative system support, appeared to be more related to successful implementation and institutionalization than to sustainability after defunding. Because the MTCP required good program design and administrative support and provided capacity building in the form of tobacco treatment training and certification programs before defunding, sustaining programs had a solid foundation on which to build, so they did not simply return to business as usual when defunding occurred. We also found that engaging in creative funding and staffing and creating a demand for services were more important in relation to the adaptations needed for early sustainability after defunding than in relation to institutionalization. Thus, our results point to the need for program planners to understand the differences between factors supporting institutionalization and those promoting sustainability.

Our findings further suggest that funders may want to require prospective service agencies to have grant-writing and marketing capabilities as well as administrative system support before funding occurs. These capabilities can be shared with other services offered by an agency, and they appear to be more effective in terms of program sustainability when they are in place before the time of funding than when they are funded within a grant.

Redefining scope of services and engaging in creative use of resources influence why certain community agencies are able to sustain services at a much higher level than others after defunding occurs. Programs can plan for sustainability by understanding these strategies and developing them at a time when program funding is not being threatened. Among other possible steps, programs may want to periodically review and consider making adjustments to the scope of the services they offer, along with developing a diversified funding base to increase their likelihood of sustainability.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute’s State and Community Tobacco Control Initiative (grant NIH R01-CA86282).

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors N. R. LaPelle assisted with study design, completed all data collection and analyses, and led the writing of the article. J. Zapka assisted in conceptualization of ideas, interpretation of findings, and the writing of the article. J. K. Ockene supervised all aspects of study implementation. All of the authors reviewed drafts of the article.

References

- 1.Bracht N, Finnegan JR, Rissel C, et al. Community ownership and program continuation following a health demonstration project. Health Educ Res. 1994; 9:243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evashwick C, Ory M. Organizational characteristics of successful innovative health care programs sustained over time. Fam Community Health. 2003;26:177–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman RM, Steckler AB. A model for the institutionalization of health promotion programs. Fam Community Health. 1989;11:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res. 1998;13:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steckler A, Goodman R. How to institutionalize health promotion programs. Am J Health Promotion. 1989;3:34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Agency for International Development. Maximizing program impact and sustainability: lessons learned in Europe and Eurasia. Available at: http://dec.usaid.gov/index.cfm. Accessed May 16, 2006.

- 7.Claquin P Sustainability of EPI: Utopia or Sine Qua Non Condition of Child Survival. Arlington, Va: Resources for Child Health Project; 1989.

- 8.Sustainability of Development Programs: A Compendium of Donor Experience. Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development; 1998.

- 9.Robbins H, Krakow M, Warner D. Adult smoking intervention programmes in Massachusetts: a comprehensive approach with promising results. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 2):II4–II7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, Md: Public Health Service; 2000.

- 11.Targeted Community Smoking Intervention Program (TCSIP). Boston, Mass: Massachusetts Dept of Public Health, Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program; 2000.

- 12.LaPelle N. Simplifying qualitative data analysis using general purpose software. Field Methods. 2004;16:85–108. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Using codes and code manuals. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999:163–177.

- 14.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Clinical research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1994:340–352.

- 15.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999:179–194.

- 16.Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. London, England: Sage Publications; 1994.

- 17.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. Case histories and case studies. In: Glaser BG, ed. More Grounded Theory Methodology. Mill Valley, Calif: Sociology Press; 1994:233–245.

- 18.Glaser BG. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Mill Valley, Calif: Sociology Press; 1998.

- 19.Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1995.

- 20.Warner D, Meneghetti A, Pbert L, et al. QuitWorks: public health/health plan collaboration in Massachusetts, linking providers and patients to telephone counseling. In: Abstracts of the National Conference on Tobacco or Health; November 2002; San Francisco, Calif. Abstract CESS-147.