Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether immunohistochemically demonstrated lymph node micrometastasis has prognostic significance in patients with histologically node-negative (pN0) hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Summary Background Data

The clinical significance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastasis recently has been evaluated in various tumors. However, no reports have addressed this issue with regard to hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Methods

A total of 954 lymph nodes from surgical specimens of 45 patients with histologically node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma who underwent macroscopically curative resection were immunostained with monoclonal antibody against cytokeratins 8 and 18. The results were examined for relationships with clinical and pathologic features and with patient survival.

Results

Lymph node micrometastases were detected immunohistochemically in 11 (24.4%) of the 45 patients, being found in 13 (1.4%) of 954 lymph nodes examined. Of the 13 nodal micrometastases, 11 (84.6%) were found in the N2 regional lymph node group rather than N1. Clinicopathologic features showed no associations with lymph node micrometastases. Survival curves were essentially similar between patients with and without micrometastasis. In addition, the grade of micrometastasis showed no effect on survival. The Cox proportional hazard model identified microscopic venous invasion, microscopic resection margin status, and histologic differentiation as significant prognostic factors in patients with pN0 disease.

Conclusions

Lymph node micrometastasis has no survival impact in patients with otherwise node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The authors do not recommend extensive lymph node sectioning with keratin immunostaining for prognostic evaluation.

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma is still the most difficult type of cholangiocarcinoma to treat, 1–3 and nodal status is known to be an important predictor of survival after resection. 4–13 We have reported that para-aortic and regional lymph nodes frequently are involved in advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma, and that extended lymphadenectomy provides a survival benefit in selected patients. 14 Identification of lymph node metastasis represents an integral component of tumor staging. Traditional histologic examination involves single sectioning of nodes sampled from resected specimens, with hematoxylin and eosin staining. This practice may underestimate the incidence of micrometastasis in lymph nodes, leading to understaging of disease. Immunohistochemical techniques using antibodies against cytokeratin can identify lymph node micrometastases missed by routine hematoxylin and eosin staining. In recent years, the clinical significance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastases has been evaluated in various cancers including those of breast, 15,16 lung, 17,18 esophagus, 19–21 stomach, 22,23 colon, 24,25 and gallbladder. 26–28 However, no reports have addressed this issue in hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastasis has prognostic significance in patients with histologically node-negative (pN0) hilar cholangiocarcinoma. For this purpose a large number of lymph nodes were examined immunohistochemically, and the impact of lymph node micrometastasis on prognosis was assessed.

METHODS

Patients and Operation

Between January 1983 and December 1999, 126 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma underwent macroscopically curative resection of the primary cancer with systematic extended lymphadenectomy, including both the regional and para-aortic nodes, at the First Department of Surgery, Nagoya University Hospital. Eleven (8.7%) patients died of postoperative complications, and 10 others had invasive cancer extending from the hepatic hilum to the distal bile duct. Of the remaining 105 patients, 48 (45.7%) had no lymph node metastasis detected by routine pathologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Three patients were excluded because the archival histologic specimens of dissected lymph nodes could not be located. The remaining 45 patients represented the study population. There were 30 men and 15 women with a mean age of 61 ± 10 years (range 38–78). Patient survival was determined from the time of surgery to the time of death or most recent follow-up. No patient was lost to follow-up.

Hepatectomy was performed in 43 (95.6%) of the 45 patients. Extrahepatic bile duct resection was performed in the remaining two patients. Combined portal vein resection with reconstruction (n = 12 [26.7%]) and pancreatoduodenectomy (n = 5 [11.1%]) also were performed in selected patients (Table 1). Extended lymph node dissection was carried out as follows. After en bloc resection of the primary tumor and nodes of the hepatoduodenal ligament and head of the pancreas with skeletonization of the portal vein and hepatic artery, the para-aortic connective tissue containing lymph nodes was dissected between the levels of the celiac and inferior mesenteric arteries. The left renal vein and the right renal artery were skeletonized between the aorta and the inferior vena cava.

Table 1. SURGICAL PROCEDURES PERFORMED

* Expressed as Couinaud’s hepatic segment(s) resected.

PV, combined portal vein resection and reconstruction; PD, combined pancreatoduodenectomy.

A total of 954 lymph nodes (21.2 nodes per patient), comprising 583 regional, 328 para-aortic, and 43 paragastric or paracolic nodes, were retrieved from the 45 surgical specimens. Archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens of lymph nodes were studied immunohistochemically.

Although all our patients had no gross residual tumor, microscopic resection margin status was judged to be positive when cancer cells were apparent on the cut surface of the resected specimen.

Lymph Node Group and Staging

Lymph node group and staging were evaluated using the TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors by the International Union Against Cancer (UICC). 29 The definitions of some regional node groups in the TNM classification are obscure; accordingly, the “General Rules for Surgical and Pathologic Studies on Cancer of the Biliary Tract,” edited by the Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery, 30 were used to define the topographic relationships of lymph nodes to surrounding structures. In this study, the hilar, cystic duct, and pericholedochal nodes in the TNM system were lumped together as the pericholedochal nodes. The periportal and proper hepatic nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament were collected together. Nodes located on the posterior surface of the pancreatic head were defined as the posterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes. The common hepatic nodes were located around the common hepatic artery.

Immunohistochemistry

Five serial sections were cut from archival tissue blocks. The first and fifth 5-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic re-examination for metastatic tumor cells, and the remaining three sections were stained with CAM 5.2 monoclonal antibody (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Immunohistochemical staining was performed with a standard streptavidin-biotin method. 31 Briefly, the paraffin sections were dewaxed, hydrated, and treated with 0.1% trypsin (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) in 0.1% calcium chloride, at pH 7.8, at 37°C for 30 minutes. Endogenous peroxide activity was blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in absolute methanol. Sections were incubated with the primary monoclonal antibody CAM 5.2 at 25 μg/mL at room temperature for 1 hour. After rinsing, the sections were incubated with secondary antibody, followed by peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan). Reaction products were visualized with diaminobenzidine as the chromogen, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

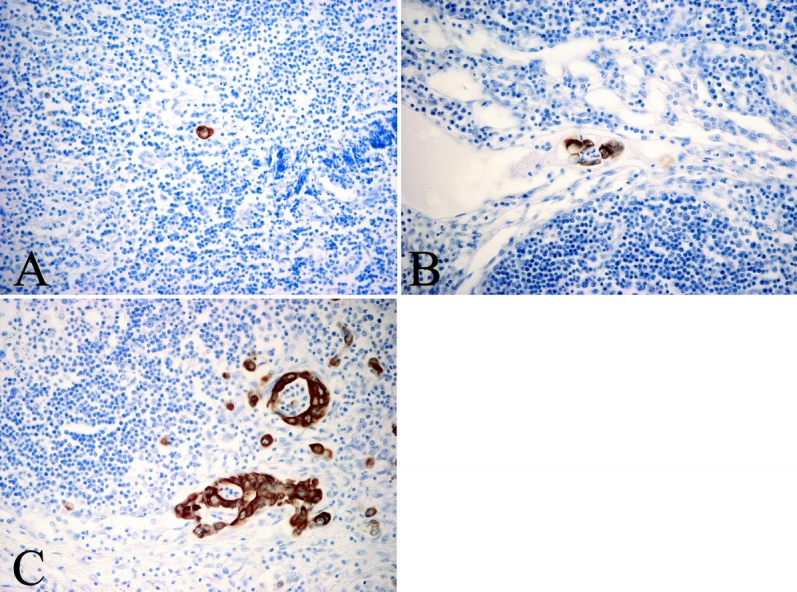

Both hematoxylin-and-eosin- and immunohistochemically stained sections were examined independently for metastasis by an experienced pathologist. Micrometastasis was recognized when tumor cells were detected only by immunostaining, having not been evident by hematoxylin and eosin staining. Lymph node micrometastases were classified into three grades (Fig. 1): grade I, single-cell metastasis; grade II, a small cluster of cancer cells; and grade III, a large cluster or multiple clusters of cancer cells.

Figure 1. Immunohistochemical staining of lymph node micrometastasis by CAM 5.2 monoclonal antibody. (A) Grade I micrometastasis. (B) Grade II micrometastasis. (C) Grade III micrometastasis.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the Fisher exact probability test and the Mann-Whitney test, where appropriate. Postoperative survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazard model was used for multivariate analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Detection of Nodal Micrometastases

Micrometastases were detected in 11 (24.4%) of the 45 patients and in 13 (1.4%) of 954 lymph nodes examined, including six grade I micrometastases, two grade II micrometastases, and five grade III micrometastases. Lymph nodes involved by micrometastasis included six periportal nodes, three common hepatic nodes, and one each among pericholedochal, posterior pancreaticoduodenal, superior mesenteric, and paragastric nodes. Of the 13 nodal micrometastases, 11 (84.6%) were found in N2 regional lymph node groups, 1 (9.1%) in N1 groups, and the remaining 1 (9.1%) in distant node groups (Table 2).

Table 2. LOCATION AND GRADE OF LYMPH NODE MICROMETASTASIS

○, single-cell metastasis (grade I); ▵, small cluster of cancer cells (grade II); □, large cluster or multiple clusters of cancer cells (grade III).

Each symbol represents one lymph node micrometastasis.

PC, pericholedochal node; PPo, periportal node; CH, common hepatic node; PPa, posterior pancreaticoduodenal node; SM, superior mesenteric node; PG, paragastric node.

Clinicopathologic details of the 45 patients with and without lymph node micrometastases are shown in Table 3; no statistically significant associations were found for the presence of lymph node micrometastases.

Table 3. CLINICOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES

* According to the TNM staging system.

Impact of Lymph Node Micrometastasis on Prognosis

The 3- and 5-year survival rates, respectively, were 63.6% and 43.6% in the 11 patients with lymph node micrometastasis, and 66.9% and 42.1% in the 34 patients without micrometastasis. Survival curves in these two patient groups were essentially similar, and the difference in survival was not statistically significant (P = .983). Of the 11 patients with lymph node micrometastasis, 4 survived more than 5 years after hepatectomy. Survival for the 45 patients with pN0 disease was significantly better than that for the 57 patients (excluding hospital death) with regional and/or para-aortic node metastasis who underwent resection during the same period (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Survival according to nodal status in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma who underwent resection including regional and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. *, by log-rank test.

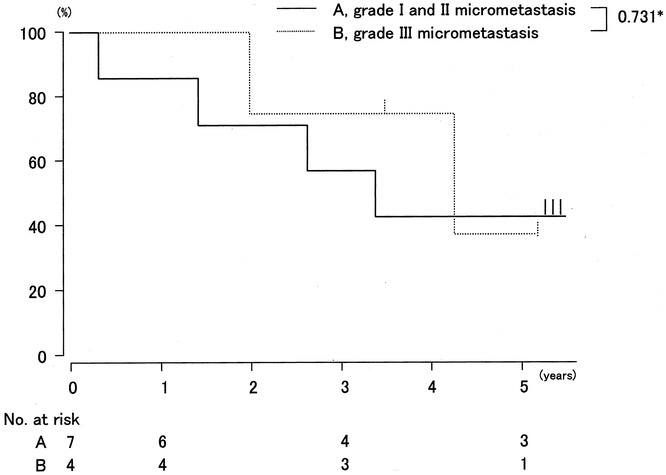

Outcomes in patients with lymph node micrometastasis were analyzed according to grade of micrometastasis. Survival rates were similar between the seven patients with grade I or II micrometastasis and the four patients with grade III micrometastasis (3-year survival, 57.1% vs. 75.0%; 5-year survival, 42.9% vs. 37.5%;P = .731;Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Survival according to grade of immunohistochemically demonstrated micrometastasis in patients with histologically negative nodes (pN0). *, by log-rank test.

Analysis of Prognostic Factors in Patients With pN0 Disease

Ten independent clinicopathologic variables were analyzed as possible prognostic factors in histologically node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma. On univariate analysis, lymphatic vessel invasion, microscopic venous invasion, histology, and microscopic resection margin status were statistically significant factors. Perineural invasion showed a marginal impact (Table 4).

Table 4. UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF SURVIVAL

* According to the TNM staging system. Parentheses indicate numbers of patients.

Multivariate analysis by the Cox proportional hazard model was performed using the above four significant and one marginal variables. On multivariate analysis, microscopic venous invasion, microscopic resection margin status, and histologic differentiation were identified as significant independent prognostic factors in patients with pN0 disease (Table 5).

Table 5. MULTIVARIATE COX REGRESSION ANALYSIS OF PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

DISCUSSION

Lymph node metastasis is known to be an important prognostic factor in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma; several authors have reported a significantly better outcome in node-negative patients than node-positive patients. 4–14 However, even in patients with pN0 disease, the 5-year survival rate following resection has been as low as 40%, 7–12,14 and tumor recurrence in such node-negative patients remains a problem. As cancer cell detection methods have developed, micrometastases that were not found by conventional histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining have been detected in various malignant tumors. We first hypothesized that the relatively low survival rate in node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma could result from the presence of lymph node micrometastasis. In the present study, lymph node micrometastasis was detected in 24% of patients with pN0 disease, but no survival impact was seen.

So far, no reports have described the significance of lymph node micrometastasis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma, perhaps because few institutions have sufficient numbers of curatively resected cases for analysis. The prognostic significance of micrometastasis has been evaluated in other gastrointestinal cancers such as esophageal, gastric, and colon cancer, but with mixed results. For instance, among three studies of lymph node micrometastasis in esophageal cancer, the authors of one report found a significant relationship between micrometastasis and decreased survival, 19 while the authors of the other two analyses failed to demonstrate a significant association. 20,21 Such contradictory patterns also have been found in gastric 22,23 and colon cancer. 24,25 In addition, several studies on breast cancer have failed to demonstrate a survival impact of lymph node micrometastasis. 15,16 Thus, no consensus on the clinical significance of lymph node micrometastasis has been reached.

A possible reason for contradictory results involves differences in the number of lymph nodes examined between studies. Wong et al. stressed that the number of nodes examined influenced staging accuracy. 32 In studies regarding esophageal cancer, mean numbers of lymph nodes examined for micrometastasis varied widely, ranging from less than 10 19,20 to 37 21 per patient. In the present study, all patients underwent systematic extended lymphadenectomy including both regional and para-aortic nodes, and a mean of 21 nodes were examined per patient, which rules out inaccuracy arising from examining insufficient numbers of nodes. Another possible reason for disagreement is different definitions of lymph node micrometastasis. In many studies micrometastasis has been defined as tumor cells detectable only by immunostaining. 19,21–23 Other authors set size criteria for micrometastasis, such as deposits less than 2 mm in diameter, 20 deposits less than 0.5 mm in diameter, 33 and deposits consisting of five cancer cells or fewer. 27,34 The 2-mm definition may include “micrometastases” detected by careful hematoxylin and eosin examination, while stricter criteria would exclude metastasis that is difficult to detect by ordinary hematoxylin and eosin staining. In the present study, lymph node metastases were classified into three grades. All micrometastases in our series were less than 0.5 mm in diameter, but included clusters with more than five cancer cells. However, no difference in prognosis was noted between grade I to II and grade III micrometastases, which indicates no effect of micrometastasis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma, irrespective of definition.

As for lymph node micrometastasis from biliary tract cancers, only three studies 26–28 were conducted in gallbladder cancer, two of which 26,27 were from the same institution. Nagakura et al. 27 examined 1,136 nodes taken from 63 gallbladder cancer patients with pN0 to 2 disease who underwent macroscopically curative resection (18 nodes examined per patient), and found micrometastases in 27 (2.3%) nodes from 19 (30.2%) patients. The total and mean number of examined nodes and the incidence of micrometastasis in their study were almost similar to the present study. However, their conclusions were different: patients with only nodal micrometastasis had a significantly decreased survival rate compared to patients with overt metastasis (18% vs. 80% 5-year survival rate). These authors concluded that lymph node micrometastasis was the strongest independent predictor of poor survival irrespective of histologic nodal status. The causes of such dramatically different results are difficult to identify even after considering possible differences in biologic behavior between gallbladder cancer and hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

We found survival rates to be nearly equal between hilar cholangiocarcinoma patients with nodal micrometastasis and those without. This might be explained by postulation that in micrometastasis the residual cancer cells may be dormant. 35 However, we suspect a different reason: the therapeutic effect of extended lymphadenectomy. Recent evidence suggests that extended lymphadenectomy may prolong survival in selected patients with gallbladder cancer 36,37 or hilar cholangiocarcinoma. 5–8,14 Boniest et al. 38 reported that regional lymphadenectomy in the hepatoduodenal ligament was effective for improving outcome in gallbladder cancer patients without overt nodal metastasis. In the present study, nodal micrometastasis occurred in about one fourth of patients with histologically node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma, while most micrometastases were found in N2 rather than N1 regional lymph node groups. Considering these observations, we recommend dissection of regional nodes including at least the pericholedochal, periportal, common hepatic, and posterior pancreaticoduodenal nodes, even if overt nodal metastasis is absent.

Multivariate analysis has shown that microscopic venous invasion, microscopic resection margin status, and histologic differentiation are significant prognostic factors in patients with node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma. To improve survival for such patients, we relied mainly on attempting to perform a microscopically curative resection. Radiotherapy may be effective when a resection margin unexpectedly is found to be positive. 10 In addition, when postoperative histologic examination reveals the presence of venous invasion or moderately or poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, adjuvant chemotherapy may be indicated despite disagreement concerning effectiveness.

In conclusion, our results indicate that lymph node micrometastasis has no survival impact in patients with histologically node-negative hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Immunohistochemical examination for lymph node micrometastasis is time-consuming and costly. We do not recommend extensive lymph node sectioning with keratin immunostaining for prognostic assessment in hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Yuji Nimura, MD, PhD, Professor and Chairman, Department of Surgery, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, 65 Tsurumai-cho, Showa-ku, Nagoya 466-8550, Japan.

E-mail: ynimura@med.nagoya-u.ac.jp

Accepted for publication June 14, 2002.

References

- 1.Tompkins RK, Saunders K, Roslyn JJ, et al. Changing patterns in diagnosis and management of bile duct cancer. Ann Surg 1990; 211: 614–621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenthaler R, Phillips TL, Castro J, et al. Carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts: The University of California at San Francisco experience. Ann Surg 1994; 219: 267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn T, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996; 224: 463–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, et al. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer: A single-center experience. Ann Surg 1996; 224: 628–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogura Y, Kawarada Y. Surgical strategies for carcinoma of the hepatic duct confluence. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishiyama S, Fuse A, Kuzu H, et al. Results of surgical treatment and prognostic factors for hepatic hilar bile duct cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 1998; 5: 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakagawa K, et al. Parenchyma-preserving hepatectomy in the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 1999; 189: 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, et al. Improved surgical results for hilar cholangiocarcinoma with procedures including major hepatic resection. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuhaus P, Jonas S, Bechstein WO, et al. Extended resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1999; 230: 808–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todoroki T, Kawamoto T, Koike N, et al. Radical resection of hilar bile duct carcinoma and predictors of survival. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsao J, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of an American and a Japanese experience. Ann Surg 2000; 232: 166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, et al. Aggressive preoperative management and extended surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2000; 7: 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhuiya MR, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Clinicopathologic factors influencing survival of patients with bile duct carcinoma: Multivariate statistical analysis. World J Surg 1993; 17: 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitagawa Y, Nagino M, Kamiya J, et al. Lymph node metastasis from hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Audit of 110 patients who underwent regional and paraaortic node dissection. Ann Surg 2001; 233: 385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuckin MA, Cummings MC, Walsh MD, et al. Occult axillary node metastases in breast cancer: their detection and prognostic significance. Br J Cancer 1996; 73: 88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clare SE, Sever SF, Wilkens W, et al. Prognostic significance of occult lymph node metastases in node-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 1997; 4: 447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein NS, Mani A, Chmielewski G, et al. Immunohistochemically detected micrometastases in peribronchial and mediastinal lymph nodes from patients with T1, N0, M0 pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohta Y, Oda M, Wu J, et al. Can tumor size be a guide for limited surgical intervention in patients with peripheral non-small cell lung cancer? Assessment from the point of view of nodal micrometastasis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001; 122: 900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izbicki JR, Hosch SB, Pichlmeier U, et al. Prognostic value of immunohistochemically identifiable tumor cells in lymph nodes of patients with completely resected esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1188–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glickman JN, Torres C, Wang HH, et al. The prognostic significance of lymph node micrometastasis in patients with esophageal carcinoma. Cancer 1999; 85: 769–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato F, Shimada Y, Li Z, et al. Lymph node micrometastasis and prognosis in patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Surg 2001; 88: 426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maehara Y, Oshiro T, Endo K, et al. Clinical significance of occult micrometastasis in lymph nodes from patients with early gastric cancer who died of recurrence. Surgery 1996; 119: 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai J, Ikeguchi M, Maeta M, et al. Micrometastasis in lymph nodes and microinvasion of the muscularis propria in primary lesions of submucosal gastric cancer. Surgery 1999; 126: 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeffers MD, O’Dowd GM, Mulcahy H, et al. The prognostic significance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastases in colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol 1994; 172: 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oberg A, Stenling R, Tavelin B, et al. Are lymph node micrometastases of any clinical significance in Dukes’ stages A and B colorectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 1244–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoyama N, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Immunohistochemical detection of lymph node micrometastases from gallbladder carcinoma using monoclonal anticytokeratin antibody. Cancer 1999; 85: 1465–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagakura S, Shirai Y, Yokoyama N, et al. Clinical significance of lymph node micrometastasis in gallbladder carcinoma. Surgery 2001; 129: 704–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tajima Y, Tomioka T, Ikematsu Y, et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of cytokeratin is useful for detecting micrometastatic foci from gall bladder carcinoma in regional lymph nodes. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1999; 29: 425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Union Against Cancer (UICC). TNM classification of malignant tumors, 5th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss, 1997.

- 30.Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery. General rules for surgical and pathological studies on cancer of biliary tract, 4th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara, 1997.

- 31.Sasaki M, Watanabe H, Jass JR, et al. Immunoperoxidase staining for cytokeratins 8 and 18 is very sensitive for detection of occult node metastasis of colorectal cancer: a comparison with genetic analysis of K-ras. Histopathology 1998; 32: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong JH, Severino R, Honnebier MB, et al. Number of nodes examined and staging accuracy in colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 2896–2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natsugoe S, Mueller J, Stein HJ, et al. Micrometastasis and tumor cell microinvolvement of lymph nodes from esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: frequency, associated tumor characteristics, and impact on prognosis. Cancer 1998; 83: 858–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komukai S, Nishimaki T, Watanabe H, et al. Significance of immunohistochemically demonstrated micrometastases to lymph nodes in esophageal cancer with histologically negative nodes. Surgery 2000; 127: 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kell MR, Winter DC, O’Sullivan GC, et al. Biological behavior and clinical implications of micrometastases. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 1629–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsukada K, Kurosaki I, Uchida K, et al. Lymph node spread from carcinoma of the gallbladder. Cancer 1997; 80: 661–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, et al. Regional and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in radical surgery for advanced gallbladder carcinoma. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boniest S, Panis Y, Fagniez P. Long-term results after curative resection for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Am J Surg 1998; 175: 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]