Abstract

In vertebrate embryos, maternal determinants are thought to preestablish the dorsoventral axis by locally activating zygotic ventral- and dorsal-specifying genes, e.g., genes encoding bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and BMP inhibitors, respectively. Whereas the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway fulfills this role dorsally, the existence of a reciprocal maternal ventralizing signal remains hypothetical. Maternal noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ signaling may promote ventral fates by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin dorsalizing signals; however, whether any maternal determinant is directly required for the activation of zygotic ventral-specifying genes is unknown. Here, we show that such a function is achieved, in part, in the zebrafish embryo by the maternally encoded transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling molecule, Radar. Loss-of-function experiments, together with epistasis analyses, identify maternal Radar as an upstream activator of bmps expression. Maternal induction of bmps by Radar is essential for zebrafish development as its removal results in larval-lethal dorsalized phenotypes. Double-morphant analyses further suggest that Radar functions through the TGF-β receptor Alk8 to initiate the expression of bmp genes. Our results support the existence of a previously uncharacterized maternal ventralizing pathway. They might further indicate that maternal TGF-β/Rdr and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways complementarily specify ventral cell fates, with the former triggering bmps expression and the latter indirectly repressing genes encoding BMP antagonists.

The degree to which the maternal genome contributes to vertebrate embryogenesis is a classical issue in developmental biology that remains largely unresolved. Pioneering work in amphibians, however, has led to models stressing its importance, especially in the control of early embryonic dorsoventral (DV) patterning (1, 2). Smith (3), for example, advanced a classical model for mesoderm induction that relied, in part, on two maternal signals: (i) a ventralizing signal emanating from ventral vegetal blastomeres inducing ventral mesoderm; and (ii) a reciprocal vegetal dorsalizing signal, inducing the Spemann organizer in the overlying prospective dorsal mesoderm. Since the establishment of this model, substantial efforts have been made to identify the molecules involved in both induction processes.

Studies in Xenopus and zebrafish have shown that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway likely underlies the maternal dorsalizing signal. Members of the pathway, including Dishevelled and β-catenin, are dorsally enriched as soon as the first cell cycle of Xenopus development (4, 5). In zebrafish, β-catenin and the ichabod (ich) gene product, which ensures nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, are essential for dorsal specification. In heterozygous embryos derived from ich homozygous mutant mothers, the activation of zygotic dorsal-specifying genes (e.g., chordino (din)/chordin, goosecoid, the homeobox gene bozozok (boz)/dharma, and the nodal gene squint) is abolished. As a consequence, ich mutants fail to form a dorsal organizer and develop as ventralized embryos in which dorsal structures are lost whereas ventral tissues expand (6). Because boz and din synergistically interact to inhibit zygotic ventralizing morphogens, namely bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), the ich phenotype is likely due in part to bmps gain-of-function (7–11). Indeed, the expression of bmp2b and bmp4 ectopically expands from ventrolateral regions into dorsal regions of ich gastrulae, thereby promoting ventral fates in cells that would normally give rise to dorsal mesoderm (6). Xenopus embryos depleted of β-catenin phenocopy ich as they are ventralized, and as they fail to express Chordin, nodal-related Xnr3, and the homeobox gene Siamois (2). Similarly, mice deficient for β-catenin fail to develop primary axes (12). Thus, the predicted maternal dorsalizing signal operates in the early embryo through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, the role of which is to trigger the expression of zygotic dorsal-specifying genes.

The existence of a reciprocal maternal determinant required for the activation of zygotic ventral-specifying genes has remained highly controversial (1, 2). The current assumption is that ventral, as opposed to dorsal, is the default state of the early embryo (13). However, this concept is in disagreement with the fact that dorsalized phenotypes may result from ventral vegetal blastomere ablations in frog embryos at stages prior to the activation of zygotic transcription (14). In addition, maternal Wnt signaling, acting through a noncanonical pathway increasing intracellular calcium levels (the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway), has been proposed to influence cells to adopt ventral fates in Xenopus by promoting nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor XNF-AT (15–17). This event would in turn suppress canonical Wnt/β-catenin dorsalizing signals and result in embryonic ventralization (17). However, whether XNF-AT directly induces the expression of zygotic ventral-specifying genes such as bmps is not known.

We have previously argued against the idea that the onset of bmps expression does not require induction because it could be enhanced on misexpression of zebrafish radar (rdr) mRNA, which encodes a secreted transforming growth factor (TGF)-β molecule homologous to mammalian GDF6 (18, 19). Interestingly, rdr mRNA is maternally supplied in the zebrafish egg (18). Together with its gain-of-function phenotype, its early expression suggests that maternal rdr (Mrdr) could play a role in the early regulation of bmps. The loss-of-Mrdr function studies and epistasis analyses presented here show that this is indeed the case in vivo and also strongly suggest that Mrdr specifically activates bmps expression through an MRdr (ligand)/Alk8 (receptor) signaling pathway. Our results identify zebrafish Radar (Rdr) as the first vertebrate maternal activator of zygotic ventral-specifying genes, and thus support pioneer models stressing that ventral specification requires maternal induction (3).

Materials and Methods

Genetics.

Mutant alleles used were bmp2b (swrta72), bmp7 (snhty68a), smad5 (sbndtc24), and chordin (dintt250) (20, 21). Maternal-zygotic (MZ) lost-a-fin (MZlaf) loss-of-function mutations in alk8 were phenocopied by using alk8 morphants (22) (23). Dorsalized and ventralized phenotypes have been described (C1–C5 and V1–V5, respectively, with 1 the mildest and 5 the strongest; refs. 20 and 24).

Morpholinos.

Morpholino (MO) antisense oligonucleotides rdratgMO (5′-ATcatGGGTGTTACTATCCTCCAAAGA-3′) and rdrgtMO (5′-GCAATACAAacCTTTTCCCTTGTCC-3′) were provided by Gene Tools (Corvallis, OR). rdr exon/intron boundaries were determined using the zebrafish genome draft assembly (www.ensembl.org/Daniorerio/). The exon 1/intron 1 boundary (coding nucleotide +463) was selected for MO targeting. rdratgMO specificity tests were carried out according to ref. 25. The in vivo specificity and efficiency of rdrgtMO were monitored via semiquantitative RT-PCR. Briefly, mRNA was extracted from uninjected and rdrgtMO-injected embryos at 24–30 h postfertilization (hpf), reverse transcribed, and PCR amplified by using primers located in exons 1 and 2, respectively. PCR products were gel-eluted and sequenced.

cDNAs and Synthetic mRNAs.

rdrDN cDNA was generated by removing the terminal 156 bp of the coding 3′ end of rdr cDNA. The truncated RdrDN isoform is predicted to lack, in its C terminus, 52 aa that are critical for ligand activity. Injections of rdr and rdrDN mRNAs reproducibly led to a small proportion of embryos (20%) exhibiting abnormal gastrulation movements that could reflect a requirement for Rdr or a related molecule in gastrulation movements. These embryos were omitted in our calculations of frequencies of rdr- and rdrDN-induced DV patterning phenotypes.

Injections and Whole Mount in Situ Hybridization.

RNA transcriptions, mRNA/MO injections, and in situ hybridization were performed as described (18, 23).

In Vitro Translation.

rdr full-length mRNA (1 μg) or alk8 mRNA (1 μg) were translated in vitro by using a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system in the presence or absence of rdrMO or alk8 MO in a reaction volume of 25 μl. The translation products were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and detected by autoradiography.

Results and Discussion

Zebrafish Rdr is supplied as a maternal RNA deposited in the egg, and is later on expressed zygotically during early embryogenesis. However, zygotic rdr transcripts are first detectable at the end of gastrulation, i.e., a few hours after the first time point of embryonic DV patterning (onset of gastrulation; refs. 18 and 19); and haploid embryos carrying a deletion that encompasses rdr (rdrΔ1) develop a normal DV axis (26). Together, these observations indicate that zygotic rdr (Zrdr) activity is not essential for embryonic DV patterning. To further confirm this notion, we analyzed the phenotypes of embryos injected with an MO targeted to a splice donor site of the rdr premature mRNA. Such “gtMOs” interfere with splicing of newly synthesized (i.e., zygotic) mRNAs but leave maternal mRNAs intact (27). rdrgtMO, which is targeted to the first exon/intron boundary of rdr, is expected to prevent splicing of intron 1. The resulting frameshift generates a Rdr variant truncated within the pro-domain (K112fsX156) and leads to a zygotic strong loss-of-function situation whereby no C-terminal mature protein is produced. Injections of rdrgtMO in WT embryos led to a fully penetrant (95%, n = 99) phenocopy of the rdrΔ1 haploid phenotype. The morphants developed a normal DV axis but exhibited reduced eyes and massive cell death in the head and in the dorsal neural tube starting at late somitogenesis (Fig. 1B), fully consistent with the zygotic expression of Rdr in the dorsal tube from the end of gastrulation (19). Furthermore, this phenotype was reversed by coinjection of WT Rdr RNA (data not shown), arguing for specificity. The morphant phenotype was correlated, as predicted, with a retention of intron 1 in rdr morphant transcripts (Fig. 1C). Together, the absence of DV patterning defects in Zrdr null mutants (rdrΔ1 haploids) and morphants (referred to as ZrdrMO embryos) demonstrates that embryonic rdr products are not required for DV axis formation.

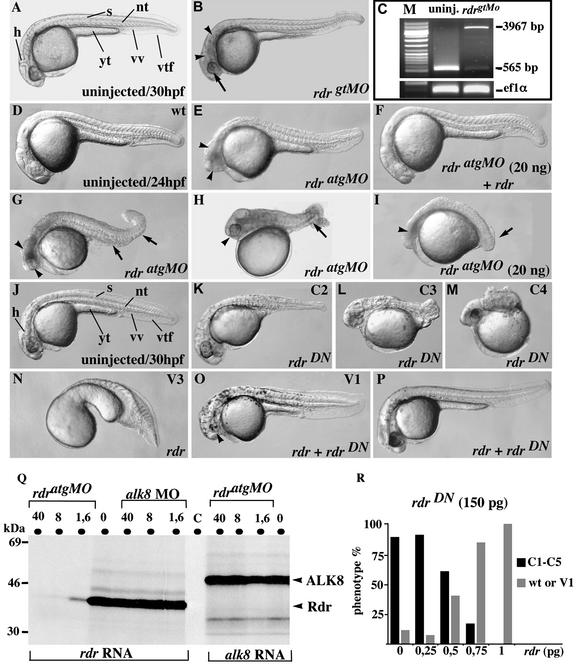

Figure 1.

Loss-of-Mrdr function specifically results in dorsalized phenotypes. (A and B) Live embryos at 30 hpf, either uninjected (A) or injected with rdrgtMO (10 ng; B) showing all characteristics of rdrΔ1 zygotic mutant haploids, including reduced eyes (arrow) and neural cell death (arrowheads). (C) RT-PCR products of transcripts from uninjected and rdrgtMO-injected embryos using primers amplifying the region of the targeted splicing event were run on a 3% agarose gel. The morphant PCR product has the expected size (3,967 kb) and sequence of a transcript retaining intron 1. ef1α amplimers are shown as reverse transcription quantitative controls. (D–P) Live embryos at 24 hpf (D–I) and 30 hpf (J–P) either uninjected (D and J) or injected (E–I and K–P) with the MOs/mRNAs described in each right lower corner. Unless stated otherwise, doses used per embryo were rdr (1 pg), rdrDN (150 pg), and rdratgMO (15 ng). Arrowheads and arrows in E and G–I denote ZrdrMO and MrdrMO features, respectively. (K–M) C2–C4 dorsalized rdrDN-injected embryos. (N and O) V3 (strong) and V1 (mild) ventralized embryos. Arrowhead in O marks the V1-characteristic reduced eye size. All views are lateral, anterior to the left. h, head; s, somite; nt, notochord; yt, yolk tube; vv, ventral vein; vtf, ventral tail fin. (Q) rdratgMO specifically blocks rdr mRNA but not alk8 mRNA translation in vitro. rdr (Left) or alk8 (Right) mRNAs (1 μg) were translated in vitro in the presence of rdratgMO or alk8MO at the indicated concentrations (40, 8, 1.6, or 0 μM), then translation products were resolved. (C) No mRNA added in the translation reaction. (P and R) Rescue of rdrDN phenotypes with rdr mRNA.

To investigate whether Mrdr (which is ubiquitously expressed in the early embryo; ref. 18) could be required in this process, we sought to carry out loss-of-Mrdr function experiments. In contrast to gtMOs, MOs targeted to the 5′ end of transcripts (“atgMOs”) have been shown to interfere not only with zygotic, but also with maternal gene function in zebrafish (23, 28). Injections of rdratgMO abolished Zrdr function and led to a fully penetrant phenocopy (96%, n = 457) of the rdrΔ1 and ZrdrMO phenotypes (Fig. 1 B and E). Strikingly, however, nearly 50% of rdratgMO-injected embryos differed from rdrΔ1 and rdrgtMO embryos in that they displayed an additional, superimposed dorsalized phenotype (Fig. 1 G–I). The strength of the rdratgMO-specific dorsalized phenotype was moderate (C1–C3) compared with the strong dorsalized traits (C4–C5) produced by null alleles of bmp2b and bmp7 (see below). The dorsalized phenotype of rdratgMO embryos could arise either from a removal of Mrdr activity, consistent with the ventralized phenotype produced by rdr gain-of-function (18), or could result from unspecific effects of the atgMO.

To decide between both hypotheses, we tested the specificity of rdratgMO toward the rdr transcript. We first carried out mRNA rescue experiments. Whereas coinjection of rdratgMO with gfp mRNA had no effect on the frequency of the dorsalized and ZrdrMO phenotypes and on GFP activity (data not shown), a complete rescue of both phenotypes was observed on coinjection with rdr mRNA devoid of the MO target site (97% WT, n = 102; Fig. 1, compare F with I). In addition, rdratgMO specifically interfered, in an in vitro translation assay, with Rdr but not with Alk8 protein synthesis (Fig. 1Q). Altogether, these results demonstrated that rdratgMO specifically knocks down rdr function in vivo. Hence, it is very likely that both maternal and zygotic contributions are removed in those rdratgMO morphants exhibiting both dorsalized and ZrdrMO phenotypes, which we refer to as maternal-zygotic rdr morphants (MZrdrMO). Similarly, we hereafter refer to the dorsalized phenotype alone as the maternal morphant phenotype (MrdrMO). The incomplete penetrance (overall average of 47%; n = 457; Table 1) and the variable expressivity (C1–C3) of the MrdrMO condition suggest that some MRdr protein is present before MO injection, and may partially compensate for the depletion of the maternal mRNA supply. Alternatively, MRdr may be partially redundant with another early provided ventralizing factor.

Table 1.

Injection studies in WT and DV mutant backgrounds

| Cross (female × male) | mRNA, pg per embryo or MO, ng per embryo | Phenotypes† | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ × +/+ | rdr (1) | 56% V1–V2, 44% V3–V4 | 78 |

| swr/swr × swr/swr | — | 100% C5 | 133 |

| rdr (1) | 100% C5 | 61 | |

| snh/snh × snh/snh | — | 100% C4 | 119 |

| rdr (1) | 100% C4 | 79 | |

| sbn/+ × +/+ | — | 100% C4–C5 | 33 |

| rdr (15) | 80% C4–C5, 20% C2–C3 | 25 | |

| +/+ × +/+ | rdratgMO (5) | 47% C1–C3, 53% WT | 457 |

| alk8MO (5) | 86% C4–C5, 14% C2–C3 | 41 | |

| alk8MO (5) + rdr (1) | 81% C4–C5, 19% C3 | 88 | |

| bmp2b (1) | 100% V3–V4 | 30 | |

| rdratgMO (15) + bmp2b (1) | 95% V3–V4, 5% V1–V2 | 40 | |

| alk3* (5) | 100% V3–V4 | 31 | |

| rdratgMO (15) + alk3* (5) | 100% V3–V4 | 44 | |

| din/din × din/+ | — | 48% V1–V2, 52% WT | 150 |

| rdratgMO (15) | 5% V1, 46% C1–C3, 49% WT | 76 | |

| +/+ × +/+ | alk8MO (1) | 11% C1, 89% WT | 48 |

| rdratgMO (1) | 3% C2, 3% C1, 94% WT | 39 | |

| alk8MO (1) + rdratgMO (1) | 38% C5, 53% C4, 9% C3 | 66 |

For simplicity, ZrdrMO phenotypes are not indicated. n, number injected.

To further confirm that MRdr is required for DV pattern formation, we generated a truncated version of rdr cDNA encoding a Rdr isoform, RdrDN, devoid of 52 aa in its C-terminal mature domain. Such truncated TGF-β variants may exhibit dominant-negative (DN) properties when injected in vivo, probably by forming inactive heterodimers with endogenous WT monomers (29). To directly address this issue, we tested the ability of RdrDN to abolish the ventralizing effects of ectopic Rdr activity by coinjecting both mRNAs. As expected from rdr ventralizing activity (18), 100% (n = 78) of embryos injected with rdr were strongly ventralized (Fig. 1N). In contrast, only 11% (n = 76) of embryos coinjected with rdr and rdrDN still showed some ventralized features (Fig. 1O), and 89% displayed a completely rescued WT phenotype (Fig. 1P). These results showed that RdrDN behaves as a dominant inhibitor of Rdr activity in vivo. We then analyzed the phenotype of WT embryos overexpressing rdrDN mRNA alone. Consistent with the MrdrMO dorsalized phenotype, rdrDN overexpression led to dorsalized phenotypes of variable strength (C1–C5) in a dose-dependent fashion (highest efficiency: 150 pg mRNA per embryo, 87% dorsalized, n = 377; Fig. 1 J–M). These phenotypes, similarly to the MrdrMO phenotypes, were completely rescued by rdr mRNA (Fig. 1R). Taken together, the dorsalizing effects of both rdratgMO and rdrDN strongly suggest that Mrdr is required to promote ventral cell fates during DV axis formation.

To understand how Mrdr regulates DV patterning, we first analyzed rdratgMO- and rdrDN-injected gastrulae for modifications in the expression patterns of ventral and dorsal markers by in situ hybridization. Fig. 2 A–H shows strongly affected rdrDN injected embryos in which the characteristic ventrolateral bmps expression pattern is virtually abolished, whereas the expression of the dorsal antagonist chordin expands ventrolaterally. Therefore, rdrDN acts at or before gastrulation to regulate the size of the dorsal and the ventral domains. In contrast to rdrDN gastrulae, rdratgMO gastrulae exhibited normal levels of bmp7 expression and only a moderate decrease in bmp2b levels (50%, n = 45; data not shown). bmp4 transcripts, however, were also virtually absent in morphant gastrulae. The expression of bmps during gastrulation relies on BMP activity (30–32). Therefore, either a loss of bmps expression or an increase in the expression of bmp antagonists before gastrulation could account for the down-regulation of bmp expression observed in injected gastrulae. Consistent with the former idea, a strong down-regulation of bmp2b and -4 genes was observed in an average of 50% of morphants in late blastulae (Fig. 2 I–K, M, and N; n > 40 for each probe). Similarly, the expression of all bmp genes, including bmp7 (Fig. 2O), was abolished in an average of 70% of rdrDN blastulae. In contrast, the onset of the bmp antagonists din/chordin and boz/dharma expression was unaffected in both morphants and antimorphs (Fig. 2 L and P and data not shown). Likewise, the expression of other regulators of the DV axis, like the ventralizing homeobox genes vega1/vega2 (33) or the dorsalizing genes cyclops and squint (34, 35), were not affected in morphants (data not shown). We conclude that the dorsalization induced by rdratgMO and rdrDN is an early phenomenon, and is likely the result of an early reduction of bmp expression rather than the consequence of an increase in the levels of bmp antagonists.

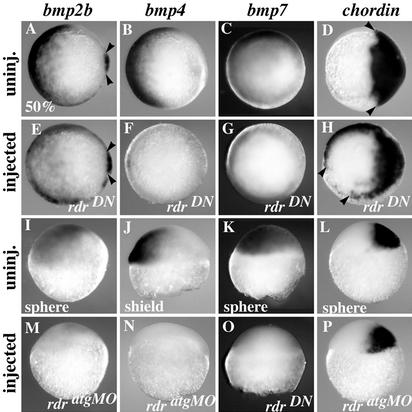

Figure 2.

Loss-of-Mrdr function results in down-regulation of early bmp expression. Expression profiles of bmp2b (Left), bmp4 (Center Left), bmp7 (Center Right), and chordin (Right) in uninjected (A–D) and rdrDN-injected (E–H) early gastrulae (50% epiboly), and in uninjected (I–L) and injected (M–P) embryos at indicated stages of initiation of gene expression. (M, N, and P) rdratgMO-injected and (O) rdrDN-injected are shown. Arrowheads in A and E point to the dorsal (shield) territory of bmp2b expression (24), which, in contrast to the ventrolateral territory, was not affected by rdrDN. Arrowheads in D and H indicate the limits of chordin expression domain. A–H and I–P are animal pole and lateral views, respectively, dorsal to the right.

There are significant differences between the rdr morphant and DN dorsalized phenotypes. First, the initiation and the maintenance of bmp7 are affected only in rdrDN-injected embryos. Second, although the initiation of bmp2b and bmp4 are similarly affected in both morphants and antimorphs, the maintenance of bmp2b seems only slightly affected in morphants whereas it is nearly abolished in antimorphs. Third, and probably the consequence of these differences in bmps expression profiles, rdrDN-induced morphological dorsalization (C1–C5) is stronger than that observed in rdratgMO-injected embryos (C1–C3). These differences might result from the interference of rdrDN with related molecules (29). Hence, we cannot rule out that the RdrDN stronger effects on bmps expression observed during gastrulation are caused by unspecific interference with BMP2b/4/7-positive autoregulatory loops (30–32). Importantly, however, the expression of bmps at earlier stages (i.e., blastula) does not rely on BMP2b/4/7 activity (24, 30–32, 36). Thus, the lack of initiation of bmps observed in rdrDN embryos implies that MRdr activity, and/or an MRdr-related signal, is required for the onset of bmps expression. Because the onset of bmp7 expression was not affected in rdratgMO embryos, this gene probably requires an MRdr-related factor rather than MRdr itself. Importantly, however, the lack of initiation of bmp2b and bmp4 in MrdrMO embryos strongly supports the notion that rdr encodes a maternal ventralizing factor essential for the induction of specific zygotic ventralizing genes.

To directly test whether rdr acts upstream of the canonical zygotic bmp pathway as a positive regulator, we carried out a series of epistasis analyses. Mutations in bmp pathway genes, encoding either BMP ligands, receptors (Alks), or intracellular transducers (Smads), all produce dorsalized phenotypes resulting from the removal of BMPs ventral influences and BMPs→Alks→Smads→bmps positive feedback loops (22–24, 30–32, 36). We first injected rdr mRNA into these dorsalized mutants. We reasoned that if Mrdr were specifically required for the induction of bmp expression, then its ventralizing properties would not rescue downstream bmp pathway mutant phenotypes.

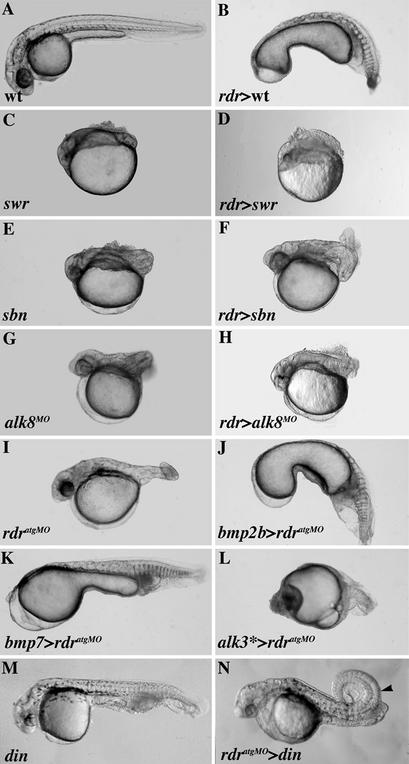

The swirl (swr) and snailhouse (snh) mutations inactivate bmp2b and bmp7, respectively. Similarly, the somitabun (sbn) mutation generates a dominant maternal-effect smad5 antimorphic allele (sbndtc24). Ectopic rdr expression in swr and snh homozygotes or in embryos from sbn heterozygous mothers did not rescue their dorsalized phenotype (Table 1; Fig. 3 C–F). Similarly, rdr misexpression had no influence on the phenotype of alk8 morphants (Table 1; Fig. 3 G and H). Furthermore, misexpression of bmp2b, bmp4, and bmp7, and of a constitutively active isoform of alk3 (alk3*) fully reversed the dorsalized phenotype of MZrdrMO embryos (Table 1; Fig. 3 I–L; data not shown). Finally, we analyzed the phenotypes of rdr;chordin double loss-of-function embryos, obtained by injecting rdratgMO in chordino (din) mutants. din mutant phenotypes were rescued to WT or dorsalized phenotypes in response to loss-of-Mrdr function (Table 1; Fig. 3 M and N), indicating that rdratgMO-mediated dorsalization persists when Chordin is removed. This result is consistent with MRdr acting on early bmp2b expression in a step prior to initial BMP2b activity that is normally up-regulated in din homozygous mutants (8, 9). Altogether, these experiments clearly place rdr upstream of the bmp pathway.

Figure 3.

rdr acts upstream of the bmp pathway. (A) Uninjected WT embryo. (B) rdr-injected embryo showing a V3 phenotype. (C–H) Indicated dorsalized mutants or morphants (Left) do not respond to rdr ventralizing activity (Right). (I) rdratgMO-injected embryo showing the MZrdrMO phenotype. (J–L) MZrdrMO phenotypes were reversed to strongly ventralized phenotypes by raising BMP levels via injections of the indicated mRNAs. (M) din-ventralized mutant. (N) rdratgMO-injected din mutant showing some dorsalized features (arrowhead). All embryos were photographed alive at 30 hpf.

Based on our loss-of-function and epistasis results, we propose that Rdr is a maternal ventralizing factor that exerts its function by triggering bmp2b and bmp4 expression. This scheme raises the question of Rdr's identity of Rdr's receptor(s). Interestingly, the TGF-β receptor Alk8 is maternally supplied in the zebrafish blastula, and MZlost-a-fin/alk8 mutants and alk8 morphants are strongly dorsalized (22, 23). In addition, alk8 is epistatic to rdr (Table 1). Together, these observations indicated that MRdr could signal through Alk8 to induce bmp2b/4 expression.

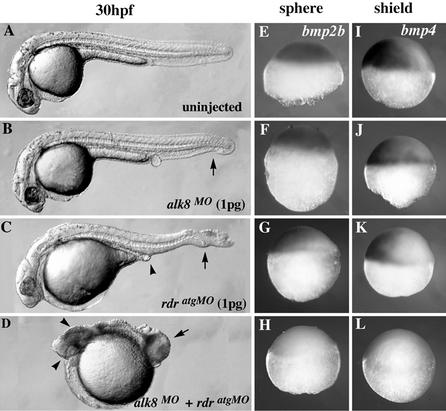

As a first step to test this possibility, we compared the phenotypes of rdratgMO and alk8MO single- and double-morphants at subinhibitory concentrations of MOs (Table 1 and Fig. 4). In striking contrast to the occasional (<10%) appearance of C1–C2 phenotypes within clutches of low-dose single-morphants (Table 1 and Fig. 4 B and C), all coinjected embryos exhibited severe dorsalized features ranging from C3 to C5 (Table 1 and Fig. 4D). Furthermore, whereas the initiation of bmp2b and bmp4 was not obviously affected in low-dose single-morphants (Fig. 4 F, G, J, and K), it was eliminated in rdr;alk8 double-morphants (Fig. 4 H and L). Together, these results show that Mrdr and alk8 strongly interact to positively regulate the onset of bmp2b/4 expression. The nature of this interaction is clearly synergistic because simple additive effects would have produced a frequency of C3–C5 double-morphant phenotypes equal to the sum of the frequencies of C1–C2 single-morphant phenotypes (<20%). Although it cannot be ruled out that the synergistic Mrdr/alk8 interaction results from both partners acting through redundant parallel pathways, it is tempting to explain this synergy by an MRdr/Alk8 ligand/receptor direct interaction.

Figure 4.

Synergistic loss of the initiation of bmp2b/4 in rdr;alk8 double-morphants. WT embryos were injected with indicated MO(s) at subinhibitory concentrations and pictured live at 30 hpf (A–D) or were processed for in situ hybridization with bmp2b (E–H) or bmp4 (I–L) probes at sphere (4 hpf) and shield (6 hpf) stages, respectively. All views are lateral, anterior (A–D) or ventral (E–L) to the left. (A) Uninjected control. (B and C) A minority of low-dose single-morphants showed C1–C2 phenotypes (Table 1). Arrows in B and C show loss of ventral tail fin; arrowhead in C shows absence of ventral vein and yolk tube. (D) Double-morphants displayed a C4–C5 phenotype ventroposteriorally (arrow) and a ZrdrMO phenotype anteriorally (arrowheads). (E–I) WT expression patterns of bmp2b and bmp4. (F and J) All low-dose alk8 morphants examined (n = 45) initiated bmps properly. (G and K) Only 4% (n = 50) of rdrMO-injected embryos were slightly affected in the initiations of bmp2b and bmp4, correlating with the frequency of C2 phenotypes among rdr morphants observed at 30 hpf (C, Table 1). (H and L) All double-morphants examined (n = 50) failed to initiate bmp.

Interestingly, sbn is epistatic to rdr (Table 1), suggesting that Smad5 might transduce MRdr/Alk8 signals. However, two observations show that this is not the case. First, rdr morphants are less dorsalized (C1–C3) than sbn embryos (C4–C5; see Table 1 and refs. 32 and 37). Second, it has recently been reported that several null alleles of sbn/smad5 affect the initiation of bmp7 expression but have no effect on the initiation of bmp2b, which contrasts with the effects of rdratgMO (37). The sbn allele we used, however, encodes an antimorph that inhibits not only Smad5 but also other Smads that might also be epistatic to rdr. Rdr could, for example, function through Smad1 or Smad8 to initiate bmps. This hypothesis of a maternal rdr→alk8→smad1/8 pathway is supported by a recent study (38) in Xenopus demonstrating that early Smad1/5/8 activity is independent of the onset of zygotic transcription. This observation is also in agreement with (i) the timing of bmp2b expression triggering by MRdr, and (ii) the involved BMP ligand and receptor being maternally supplied, which is the case for Rdr and Alk8. Finally, this study might further indicate that a MRdr-like pathway operates in the amphibian blastula. Whether Xenopus GDF6 (an rdr homolog) could be involved seems unlikely because XGDF6 transcripts are first detected after the onset of zygotic transcription (39). Yet it is possible that maternal XGDF6 proteins translated during oogenesis are active in the early frog embryo. Alternatively, maternally supplied BMPs (1, 2) could fulfil the function of MRdr in amphibians.

To our knowledge, MRdr seems to date as the first vertebrate maternal ventralizing factor with assigned target genes, bmps. The existence of such a factor strongly argues against the widely held assumption that ventral is the ground state of the early vertebrate embryo (13). Our results support classical models instead, which propose that ventral fates, like dorsal fates, require maternal induction (3). Our conclusions in zebrafish further meet those of recent studies suggesting that a maternal ventralizing signal also operates in Xenopus (15–17). The frog embryo seems to use the maternal Wnt/Ca2+ pathway to regulate early ventral specification. However, whereas MRdr directly promotes ventral fates by inducing the expression of zygotic ventral-specifying genes, Wnt/Ca2+ signals ventralize by suppressing maternal dorsalizing Wnt/β-catenin signals (17). Further studies will establish whether the MRdr and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways reciprocally operate in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos, respectively, and whether they cooperatively interact to induce ventral fates.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Steinbeisser, M. Hammerschmidt, and M. Mullins for helpful discussions, and B. Schmid, H. Roehl, S. Holley, and members of our laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript, as well as M. Hammerschmidt for sharing data before publication. We acknowledge F. Bouallague for fish care. We are grateful to the many colleagues who provided probes and mutants. This work was supported by a grant from Ministère de la Recherche et de l'Espace (to S.S.) and by grants from Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, Association Française Contre les Myopathies, and Ministère de la Recherche et de l'Espace Actions Coordonnées Incitatives (to F.M.R.).

Abbreviations

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- Rdr

Radar

- MZ

maternal-zygotic

- DN

dominant-negative

- MO

morpholino

- DV

dorsoventral

- hpf

hours postfertilization

- TGF

transforming growth factor

References

- 1.Harland R, Gerhart J. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:611–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heasman J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:4179–4191. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith J C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1989;105:665–677. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larabell C A, Torres M, Rowning B A, Yost C, Miller J R, Wu M, Kimelman D, Moon R T. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1123–1136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller J R, Rowning B A, Larabell C A, Yang-Snyder J A, Bates R L, Moon R T. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:427–437. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly C, Chin A J, Leatherman J L, Kozlowski D J, Weinberg E S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:3899–3911. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez E M, Fekany-Lee K, Carmany-Rampey A, Erter C, Topczewski J, Wright C V, Solnica-Krezel L. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3087–3092. doi: 10.1101/gad.852400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammerschmidt M, Serbedzija G N, McMahon A P. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2452–2461. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulte-Merker S, Lee K J, McMahon A P, Hammerschmidt M. Nature. 1997;387:862–863. doi: 10.1038/43092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koos D S, Ho R K. Dev Biol. 1999;215:190–207. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fekany K, Yamanaka Y, Leung T, Sirotkin H I, Topczewski J, Gates M A, Hibi M, Renucci A, Stemple D, Radbill A, et al. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:1427–1438. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.7.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huelsken J, Vogel R, Brinkmann V, Erdmann B, Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:567–578. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munoz-Sanjuan I, Brivanlou A H. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:271–280. doi: 10.1038/nrn786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kageura H. Dev Biol. 1995;170:376–386. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh K, Sokol S Y. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2328–2336. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhl M, Sheldahl L C, Malbon C C, Moon R T. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12701–12711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saneyoshi T, Kume S, Amasaki Y, Mikoshiba K. Nature. 2002;417:295–299. doi: 10.1038/417295a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goutel C, Kishimoto Y, Schulte-Merker S, Rosa F. Mech Dev. 2000;99:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00470-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rissi M, Wittbrodt J, Delot E, Naegeli M, Rosa F M. Mech Dev. 1995;49:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)00320-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullins M C, Hammerschmidt M, Kane D A, Odenthal J, Brand M, van Eeden F J, Furutani-Seiki M, Granato M, Haffter P, Heisenberg C P, et al. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;123:81–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammerschmidt M, Pelegri F, Mullins M C, Kane D A, van Eeden F J, Granato M, Brand M, Furutani-Seiki M, Haffter P, Heisenberg C P, et al. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;123:95–102. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mintzer K A, Lee M A, Runke G, Trout J, Whitman M, Mullins M C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2001;128:859–869. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauer H, Lele Z, Rauch G J, Geisler R, Hammerschmidt M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2001;128:849–858. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishimoto Y, Lee K H, Zon L, Hammerschmidt M, Schulte-Merker S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:4457–4466. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heasman J. Dev Biol. 2002;243:209–214. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delot E, Kataoka H, Goutel C, Yan Y L, Postlethwait J, Wittbrodt J, Rosa F M. Mech Dev. 1999;85:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Draper B W, Morcos P A, Kimmel C B. Genesis. 2001;30:154–156. doi: 10.1002/gene.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasevicius A, Ekker S C. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–220. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawley S H, Wunnenberg-Stapleton K, Hashimoto C, Laurent M N, Watabe T, Blumberg B W, Cho K W. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2923–2935. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmid B, Furthauer M, Connors S A, Trout J, Thisse B, Thisse C, Mullins M C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:957–967. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dick A, Hild M, Bauer H, Imai Y, Maifeld H, Schier A F, Talbot W S, Bouwmeester T, Hammerschmidt M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:343–354. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hild M, Dick A, Rauch G J, Meier A, Bouwmeester T, Haffter P, Hammerschmidt M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:2149–2159. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawahara A, Wilm T, Solnica-Krezel L, Dawid I B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12121–12126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rebagliati M R, Toyama R, Haffter P, Dawid I B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9932–9937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sampath K, Rubinstein A L, Cheng A M, Liang J O, Fekany K, Solnica-Krezel L, Korzh V, Halpern M E, Wright C V. Nature. 1998;395:185–189. doi: 10.1038/26020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen V H, Schmid B, Trout J, Connors S A, Ekker M, Mullins M C. Dev Biol. 1998;199:93–110. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramer C, Mayr T, Nowak M, Schumacher J, Runke G, Bauer H, Wagner D S, Schmid B, Imai Y, Talbot W S, et al. Dev Biol. 2002;250:263–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faure S, Lee M A, Keller T, ten Dijke P, Whitman M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:2917–2931. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.13.2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang C, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:3347–3357. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]