Abstract

Background

Scientific interest in acupuncture has led numerous investigators to conduct clinical trials to test the efficacy of acupuncture for various conditions, but the mechanisms underlying acupuncture are poorly understood.

Methods

The author conducted a PubMed search to obtain a fair sample of acupuncture clinical trials published in English in 2005. Each article was reviewed for a physiologic rationale, as well as study objectives and outcomes, experimental and control interventions, country of origin, funding sources and journal type.

Results

Seventy-nine acupuncture clinical trials were identified. Twenty-six studies (33%) offered no physiologic rationale. Fifty-three studies (67%) posited a physiologic basis for acupuncture: 33 (62% of 53) proposed neurochemical mechanisms, 2 (4%) segmental nervous system effects, 6 (11%) autonomic nervous system regulation, 3 (6%) local effects, 5 (9%) effects on brain function and 5 (9%) other effects. No rationale was proposed for stroke; otherwise having a rationale was not associated with objective, positive or negative findings, means of intervention, country of origin, funding source or journal type. The dominant explanation for how acupuncture might work involves neurochemical responses and is not reported to be dependent on treatment objective, specific points, means or method of stimulation.

Conclusion

Many acupuncture trials fail to offer a meaningful rationale, but proposing a rationale can help investigators to develop and test a causal hypothesis, choose an appropriate control and rule out placebo effects. Acupuncture may stimulate self-regulatory processes independent of the treatment objective, points, means or methods used; this would account for acupuncture's reported benefits in so many disparate pathologic conditions.

Background

Clinical trials often test a causal association between intervention and outcome [1]. However, Ernst has asserted that, "Viewed from a scientific perspective, acupuncture is rarely, if ever, a causal therapy" [2]. Perhaps acupuncture is not causal – no more so than flipping a light switch "causes" illumination. However, if acupuncture is a causal intervention, investigators should be able to suggest a biological pathway, hypothesis or rationale for how it might work.

"How might acupuncture work?" is asked and answered on the website of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) of the National Institutes of Health: "It is proposed that acupuncture produces its effects through regulating the nervous system, thus aiding the activity of pain-killing biochemicals such as endorphins and immune system cells at specific sites in the body. In addition, studies have shown that acupuncture may alter brain chemistry by changing the release of neurotransmitters and neurohormones and, thus, affecting the parts of the central nervous system related to sensation and involuntary body functions, such as immune reactions and processes that regulate a person's blood pressure, blood flow, and body temperature"[3]. More detailed rationales for acupuncture are readily available [4].

The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Statement recommends that clinical trial authors "suggest a plausible explanation for how the intervention under investigation might work" [5]. Clinical trials of acupuncture might be more useful if they had not just a hypothesis about efficacy, but also a hypothesis about a mechanism. The purpose of this study was to determine to what extent contemporary acupuncture clinical trials proposed physiologic rationales and present the findings in the context of other characteristics of the studies.

Methods

The author sought a fair sample of acupuncture clinical trials and conducted a PubMed search using the keyword "acupuncture," further limiting the search to "clinical trials" published in "English" in "2005." The author obtained and reviewed a copy of every article identified from this search; articles were excluded if they were not actually clinical trials of acupuncture; letters and brief articles were also excluded as they were unlikely to have the details sought. Each article was reviewed for a physiologic rationale; that is, a description of any human physiologic process as an explanation linking the intervention to the outcome. Articles were also reviewed for their objectives (indications or experimental conditions) and outcomes of interest, the experimental and control interventions, country of origin, funding sources and type of journal. Rationales were not counted if based only on acupuncture theory or practice or on published or historical reports; a description of some physiologic process was required. This study had no external funding.

Results

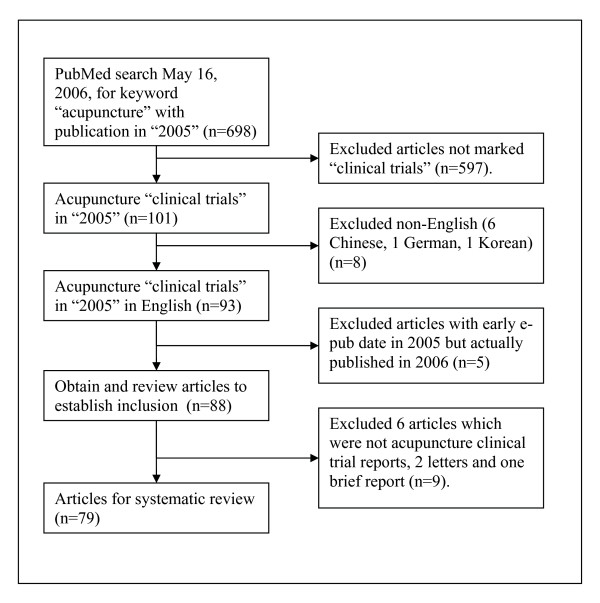

The PubMed search on May 16, 2006, using the keyword "acupuncture" yielded 698 publications in 2005; 101 were indexed as acupuncture clinical trial reports, of which 93 were published in English. Five articles had an advance e-publish date in 2005 but were formally published in 2006 and were excluded. Six articles were excluded because they were not, in fact, clinical trial reports; also, two letters and one brief article were excluded. The study sample includes all remaining articles (n = 79) [6-84]. (Figure 1) After reviewing these papers, they were categorized according to their rationale: none, neurochemical, segmental ("gate control"), autonomic regulation, local effects, functional effects in the brain or other effects.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selection of clinical trials of acupuncture.

Rationales

Twenty-six articles (33%) offered no discernible physiologic rationale for how acupuncture might work (Table 1). Indications with no rationale include addiction [42], auditory hallucinosis [35], breech presentation [13], chronic fatigue syndrome [49], chronic sinusitis [70], depression [67], irritable bowel syndrome [29], mental fatigue [32], overactive bladder syndrome [27] and stroke rehabilitation [62,80,82].

Table 1.

Rationales in clinical trials of acupuncture

| Proportion having a rationale | |

| All (N = 79) | 67% |

| Objectives | |

| Analgesia (n = 36) | 69% |

| Nausea/vomiting (n = 8) | 62% |

| Stroke (n = 3) | 0% |

| Other (n = 32) | 72% |

| Findings (positive) (n = 61) | 69% |

| Intervention | |

| Needles (n = 64) | 67% |

| Other (n = 15) | 67% |

| Country | |

| Asian (n = 19) | 74% |

| Non-Asian (n = 60) | 65% |

| Funding source | |

| None reported (n = 34) | 65% |

| NIH (n = 11) | 64% |

| German insurance (n = 4) | 50% |

| Other (n = 30) | 73% |

| Journal type | |

| Acupuncture (n = 17) | 59% |

| CAM (n = 8) | 62% |

| Medical (n = 54) | 70% |

Fifty-three articles (67%) proposed some physiologic process or mechanism attributing the effects of acupuncture to neurochemical, segmental ("gate theory"), autonomic regulation, local effects, effects on brain function or other effects. Most rationales were less specific than the NCCAM website, but at least suggested a non-metaphysical explanation, e.g., "Acupuncture functions by regulating the physiological state of the human body" [66]. Some explanations were inadequate, such as this for treating Parkinson's disease: "needles promote the release of endorphins and improve local blood flow" [20]. The best rationales were informative, albeit brief, for example, that for analgesia, "acupuncture stimuli act as a central nervous system input that can activate the descending antinociceptive pathway to release endogenous opioids to deactivate the ascending nociceptive pain pathway" [31]. Except for studies which measured specific physiologic outcomes, few studies directly tested their rationale. Studies which cited multiple rationales were assigned to the one which appeared to be primary.

The dominant rationale cited by 33 studies is that acupuncture stimulates the release of neurochemicals (usually endogenous opioids [beta endorphins, enkephalins and dynorphins] or serotonin). Among 36 studies of analgesia, this rationale was cited by 20 (56% of 36) articles [9,10,15,16,18,21,24-26,30,31,37,40,43,52-54,65,68,72]. This rationale was also used to explain the effects of acupuncture on nausea/vomiting [6,11,41,55], obesity [12], Parkinson's [20], irritable bowel [29], immune function [45], lower esophageal sphincter relaxations [84], blood pressure [71], post-menopausal vasomotor symptoms [56], colitis [83] and sleep quality [22].

Two studies identified segmental effects or "gate theory" as a primary mechanism specifically for analgesia [17,47], though five others referred secondarily to this rationale [15,24,26,30,54]. Sensory input from acupuncture is thought to block or interfere with nociceptive pain signals at a spinal level.

Six studies referred to modulatory effects of acupuncture on the autonomic nervous system [14,36,48,50,58,73]. However, several other studies that did not refer to autonomic regulation in their rationale did nonetheless measure outcomes which may reflect autonomic regulation: heart rate [21,45,48,66,82], heart rate variability [14,36,48], blood pressure [21,45,66,71,82], post-menopausal vasomotor symptoms [56] or respiration [82]. Other studies measured outcomes which also suggest possible ANS regulation: effects on smooth muscle [50], sleep quality [15,22,34], urinary continence [27], sweat rate [58], rate of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations [84] or nausea/vomiting [73].

Three studies referred to local effects of acupuncture on tissues or nerves [61] or mechanical effects on connective tissue [7,44]; other studies secondarily referred to changes in circulation [20,52,54], especially vasodilation [72], or effects on immune function[52,83].

Five studies proposed that acupuncture can have specific functional effects in the brain and used fMRI to correlate acupuncture points to specific areas of the brain with specific sensory or motor functions [38,39,63,74,78]. These raise fascinating possibilities even if no clear mechanism is posited.

Five studies suggested other rationales: that acupuncture promotes homeostasis [66], regulates brain function [59,75], affects sperm motility [64] or suggests that response to acupuncture may vary by patient genotype[60].

Objectives and outcomes

Studies used appropriate biomedical diagnostic inclusion criteria and outcome measures, although one study did rely on a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) differential diagnosis to assign subjects to a treatment group [49]. No rationale was proposed for stroke; otherwise, having a rationale was not associated with treatment objective. Sixty-one out of 79 (77%) articles had positive findings, of which 42 (70% of 61) had a rationale; having a rationale was not associated with obtaining positive findings. However, there were positive findings in 17 of 18 studies (94%) whose outcome of interest measured specific physiologic changes (brain blood flow using fMRI imaging [38,39,63,78], muscle blood flow [72], morphologic changes in sperm structure [64], association of acupuncture response to genotype [60], effect on leukocyte circulation [45], heart rate or heart rate variability [14,36,48], blood pressure [66,71], sweat rate [58], tissue impedance [7], sensations of skin piercing [61], post-menopausal vasomotor symptoms [56] or ultrasound imaging of tissue morphology [44].)

Interventions and controls

These studies utilized a variety of interventions which satisfy a textbook definition of acupuncture as "stimulation of points and channels" [85]. Sixty-four studies used some form of "puncture." Forty-seven studies used acupuncture needles [9,10,15,18-24,26,27,29,31,33,34,36-40,43-46,48,49,51-54,57,59-66,70,72,73,75-77,80,81,83]; others specified the use of electro-acupuncture [7,12,14,16,30,35,47,50,56,58,68], auricular acupuncture [42,79], plum blossom needling [28,83], or blood-letting acupuncture [82]. Fourteen studies used alternatives to needles: transcutaneous electrical stimulation [34,41,71], acupressure [8,32], toothpicks [78], small seeds [49] or wrist bands [69]; others used stimulation by low-power laser [11,25,67,74], topical ointments [6,55], or moxibustion [13]. Having a rationale was not associated with the means of intervention.

There were a variety of control procedures: "placebo" needles which do not puncture the skin, "sham" acupuncture which does puncture the skin (but at alternate points or non-points, near or far from true points), transcutaneous electrical stimulation or laser devices with the power "off", placebo ointment, usual care or alternative treatments.

Acupuncture point selection was usually based on traditional indications or functions (e.g., to balance the yin and yang). No study proposed in its rationale that the neurochemical effects of acupuncture are dependent on point selection nor were important distinctions in physiologic effects made among the various means (needles, pressure, electricity, laser, heat or ointment) or methods (depth, style, frequency or intensity) of stimulation, except for differences in sensations experienced by subjects.

Country, funding, journal type

The studies originated in 21 countries and were published in 52 different journals. No funding sources were reported in 34 studies (43%); major funding was provided by U.S. National Institutes of Health [16,19,44,76], especially NCCAM [7,9,10,32,33,38,43,47] and from German national insurance providers [46,52,54,81]. NIH-funded trials were no more likely to have a rationale than other studies. Seventeen studies were published in three journals of acupuncture or Chinese medicine [12,14,22,25,28,34-36,39,49-51,61,67,75,82,83] and eight were published in 2 journals of complementary/alternative medicine [7,32,33,41,47,60,70,73]; the remaining 54 were published in 47 medical journals. Having a rationale was not associated with country, funding source or journal type.

Discussion

Seventy-nine acupuncture clinical trials reports were reviewed and 53 (67%) had some rationale for the use of acupuncture. The study interventions stimulated points using needles, electricity, lasers, pressure, heat or ointments compared to various controls. No rationale was proposed for stroke; otherwise, having a rationale was not associated with objective, positive findings, means of intervention, country of origin, funding source or journal type. The dominant rationale involved release of neurochemicals (usually endogenous opioids [beta endorphins, enkephalins and dynorphins] or serotonin).

No study proposed that the neurochemical effects of acupuncture depend on point selection. No study claimed to select points based on neurochemical effects. However, it should be noted that the locations of traditional points are well-established and often correspond to underlying nerves; thus, the selection of traditional points over "non-points" may be justified. Also, the local and segmental effects would logically depend on the needling sites. Certainly, no study proposed that the neurochemical effects depend on means (needles, pressure, electricity, laser, heat or ointment) or method (depth, style, frequency or intensity) of stimulation. While there is great emphasis on point selection and stimulation technique in traditional acupuncture, the neurochemical response to acupuncture may not depend on them.

The neurochemical rationale was proposed not just for analgesia, but insomnia, nausea/vomiting, obesity, Parkinson's and effects on blood pressure, immune function, colitis, vasomotor symptoms and lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Further, it cannot be ruled out that other outcomes (e.g., autonomic regulation) may be secondary to neurochemical effects. Also, the same points may be stimulated for many different indications; alternatively, one indication may be treated with disparate point selections, not just between studies, but within studies, even varying by each treatment visit. This suggests that acupuncture simply stimulates self-regulatory processes and would account for acupuncture's reported benefits in so many disparate pathologic conditions.

Hypothesizing a mechanism can aid in selecting an appropriate control intervention. The sham needling with puncture may not be different in effect from "true" acupuncture and even the placebo needling is problematic: "Despite no skin penetration, the [placebo needle] tip exerted a mechanical stimulation... [which] may also excite nociceptive primary afferents. No ideal method of placebo stimulation acupuncture exists at present"[48]. In addition, placebos are also associated with neurochemical effects [24,39]. One study concluded that effects of acupuncture may well be "attributable to other mechanisms than perforation of subcutaneous tissue. Repetitive relaxation and being cared for may be just as important" [53]. In an experiment or clinical trial, the control intervention should depend on (i.e., "control for") the hypothesized mechanism and also control for so-called placebo effects. Without a theoretical mechanism and in the absence of a truly inert placebo, it can be difficult to define an appropriate control.

Finally, why is a rationale important? It is not enough to lament that "the mechanisms underlying acupuncture are still poorly understood" [80]. Understanding the physiologic basis of acupuncture may be critical to producing reliable (i.e., reproducible) results. A rationale should be offered as an explanation for the trial intervention, especially when the intervention is poorly understood. The rationale should offer a scientific hypothesis, either explanatory or pragmatic [5], to be tested explicitly or implicitly. Of course, pragmatic trials may proceed without a clear hypothesis about the mechanism involved. Ultimately, however, the effects of acupuncture must be mediated through human physiology and investigators should be able to suggest some possible mechanism(s). Proposing and testing ideas about the underlying mechanisms of acupuncture could eventually lead to a real understanding about how acupuncture does work.

Limitations

First, only articles published in English were included; six articles in Chinese were excluded [86-91] and one article in Korean was excluded [92]; but studies from Asia were well-represented: China [28,35,48-50,75,82,83], Taiwan [14,15,36], Hong Kong [17], Japan [58,78] and Korea[18,39]. Also, articles indexed in PubMed after May 16, 2006, were not included. Second, the reviewed studies were coded as "having" or "not having" a rationale, but many provided inadequate explanations linking intervention to outcome and no conclusions may be drawn as to whether any of these rationales are valid or relevant to their objectives. Also, while there were no apparent associations between having a rationale and most other characteristics (objectives, interventions, etc), no formal statistical tests were performed to confirm this. It is possible, though unlikely, that there are significant statistical associations which went unnoticed.

Conclusion

Every clinical trial should attempt to explain the use of the intervention, but many acupuncture trials fail to offer any meaningful rationale. The dominant rationale for acupuncture involves neurochemical responses which appear to be independent of objective, point selection or the means or method of stimulation; this raises questions about the beliefs underpinning this intervention and deserves further investigation. Many studies have attempted to test traditional acupuncture without a physiologic rationale, but proposing a hypothesis for how acupuncture might work is good science and costs nothing; a rationale can help investigators to develop a causal hypothesis, choose an appropriate control and rule out placebo effects. Reviewers making decisions about funding or publication of acupuncture research should seek a physiologic hypothesis from investigators.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The author conceived and designed the study; acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data; and wrote the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Bruce Fireman, Ph.D. for critical feedback and Andrew J. Karter, Ph.D., for invaluable feedback and support. This work had no funding source.

References

- Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Mayrent SL. Epidemiology in medicine. 1. Boston: Little, Brown; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst E. Acupuncture – a critical analysis. J Intern Med. 2006;259:125–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acupuncture: How might acupuncture work? 2006. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/acupuncture/#how 2-8-2006. Ref Type: Electronic Citation.

- Stux G, Hammerschlag R. Clinical Acupuncture: Scientific Basis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Lang T, CONSORT GROUP The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Dhiraaj S, Tandon M, Singh PK, Singh U, Pawar S. Evaluation of capsaicin ointment at the Korean hand acupressure point K-D2 for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1185–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn AC, Wu J, Badger GJ, Hammerschlag R, Langevin HM. Electrical impedance along connective tissue planes associated with acupuncture meridians. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2005;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkaissi A, Ledin T, Odkvist LM, Kalman S. P6 acupressure increases tolerance to nauseogenic motion stimulation in women at high risk for PONV. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:703–709. doi: 10.1007/BF03016557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assefi NP, Sherman KJ, Jacobsen C, Goldberg J, Smith WR, Buchwald D. A randomized clinical trial of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture in fibromyalgia. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:10–19. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-1-200507050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausell RB, Lao L, Bergman S, Lee WL, Berman BM. Is acupuncture analgesia an expectancy effect? Preliminary evidence based on participants' perceived assignments in two placebo-controlled trials. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:9–26. doi: 10.1177/0163278704273081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkovic D, Toljan S, Matolic M, Kralik S, Radesic L. Comparison of laser acupuncture and metoclopramide in PONV prevention in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15:37–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabioglu MT, Ergene N. Electroacupuncture therapy for weight loss reduces serum total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol levels in obese women. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:525–533. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05003132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardini F, Lombardo P, Regalia AL, Regaldo G, Zanini A, Negri MG, Panepuccia L, Todros T. A randomised controlled trial of moxibustion for breech presentation. BJOG. 2005;112:743–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Huang JL, Ting CT, Chang CS, Chen GH. Atropine-induced HRV alteration is not amended by electroacupuncture on Zusanli. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:307–314. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05002928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che-Yi C, Wen CY, Min-Tsung K, Chiu-Ching H. Acupuncture in haemodialysis patients at the Quchi (LI11) acupoint for refractory uraemic pruritus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1912–1915. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyak G, Sengupta P, Lenhardt R, Liem E, Doufas AG, Sessler DI, Akca O. The timing of acupuncture stimulation does not influence anesthetic requirement. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:387–392. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000142114.72117.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu TT, Hui-Chan CW, Chein G. A randomized clinical trial of TENS and exercise for patients with chronic neck pain. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:850–860. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr920oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Shin BC, Kim IH. Effects of myofascial-meridian stimulation therapy (mmst) on shoulder pain. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115:1175–1181. doi: 10.1080/00207450590914527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coeytaux RR, Kaufman JS, Kaptchuk TJ, Chen W, Miller WC, Callahan LF, Mann JD. A randomized, controlled trial of acupuncture for chronic daily headache. Headache. 2005;45:1113–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristian A, Katz M, Cutrone E, Walker RH. Evaluation of acupuncture in the treatment of Parkinson's disease: a double-blind pilot study. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1185–1188. doi: 10.1002/mds.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culp LB, Skarda RT, Muir WW., III Comparisons of the effects of acupuncture, electroacupuncture, and transcutaneous cranial electrical stimulation on the minimum alveolar concentration of isoflurane in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2005;66:1364–1370. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva JB, Nakamura MU, Cordeiro JA, Kulay LJ. Acupuncture for insomnia in pregnancy – a prospective, quasi-randomised, controlled study. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:47–51. doi: 10.1136/aim.23.2.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KG, Kotowski SE. Preliminary evidence of the short-term effectiveness of alternative treatments for low back pain. Technol Health Care. 2005;13:453–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs NM, Kirk K, MacSween A. The effect of real and sham acupuncture on thermal sensation and thermal pain thresholds. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1252–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebneshahidi NS, Heshmatipour M, Moghaddami A, Eghtesadi-Araghi P. The effects of laser acupuncture on chronic tension headache – a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:13–18. doi: 10.1136/aim.23.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elden H, Ladfors L, Olsen MF, Ostgaard HC, Hagberg H. Effects of acupuncture and stabilising exercises as adjunct to standard treatment in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: randomised single blind controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330:761. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38397.507014.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons SL, Otto L. Acupuncture for overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:138–143. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000163258.57895.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erqing D, Haiying L, Zhankao Z. One hundred and eighty-nine cases of acute articular soft tissue injury treated by blood-letting puncture with plum-blossom needle and cupping. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:104–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes A, Jackson S, Walter C, Quraishi S, Jacyna M, Pitcher M. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: a blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4040–4044. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gejervall AL, Stener-Victorin E, Moller A, Janson PO, Werner C, Bergh C. Electro-acupuncture versus conventional analgesia: a comparison of pain levels during oocyte aspiration and patients' experiences of well-being after surgery. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:728–735. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard G, Shen Y, Steele B, Springer N. A controlled trial of placebo versus real acupuncture. J Pain. 2005;6:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RE, Jeter J, Chan P, Higgins P, Kong FM, Fazel R, Bramson C, Gillespie B. Using acupressure to modify alertness in the classroom: a single-blinded, randomized, cross-over trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:673–679. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RE, Tian X, Williams DA, Tian TX, Cupps TR, Petzke F, Groner KH, Biswas P, Gracely RH, Clauw DJ. Treatment of fibromyalgia with formula acupuncture: investigation of needle placement, needle stimulation, and treatment frequency. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:663–671. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D, Hostmark AT, Veiersted KB, Medbo JI. Effect of intensive acupuncture on pain-related social and psychological variables for women with chronic neck and shoulder pain – an RCT with six month and three year follow up. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:52–61. doi: 10.1136/aim.23.2.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L, Cheng L. Clinical observation on treatment of auditory hallucinosis by electroacupuncture: a report of 30 cases. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:102–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ST, Chen GY, Lo HM, Lin JG, Lee YS, Kuo CD. Increase in the vagal modulation by acupuncture at neiguan point in the healthy subjects. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:157–164. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X0500276X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenin L, Brukner PD, McCrory P, Smith P, Wajswelner H, Bennell K. Effect of dry needling of gluteal muscles on straight leg raise: a randomised, placebo controlled, double blind trial. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:84–90. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.009431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Haselgrove C, Kwong KK, Kennedy DN, Makris N. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;27:479–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeun SS, Kim JS, Kim BS, Park SD, Lim EC, Choi GS, Choe BY. Acupuncture stimulation for motor cortex activities: a 3T fMRI study. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:573–578. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X0500317X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson KM, Adolfsson LE, Foldevi MO. Effects of acupuncture versus ultrasound in patients with impingement syndrome: randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2005;85:490–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabalak AA, Akcay M, Akcay F, Gogus N. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation versus ondansetron in the prevention of postoperative vomiting following pediatric tonsillectomy. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:407–413. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HC, Shin KK, Kim KK, Youn BB. The effects of the acupuncture treatment for smoking cessation in high school student smokers. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46:206–212. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Fufa DT, Gerber AJ, Rosman IS, Vangel MG, Gracely RH, Gollub RL. Psychophysical outcomes from a randomized pilot study of manual, electro, and sham acupuncture treatment on experimentally induced thermal pain. J Pain. 2005;6:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konofagou EE, Langevin HM. Using ultrasound to understand acupuncture. Acupuncture needle manipulation and its effect on connective tissue. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2005;24:41–46. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2005.1411347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou W, Bell JD, Gareus I, Pacheco-Lopez G, Goebel MU, Spahn G, Stratmann M, Janssen OE, Schedlowski M, Dobos GJ. Repeated acupuncture treatment affects leukocyte circulation in healthy young male subjects: a randomized single-blind two-period crossover study. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukuk P, Lungenhausen M, Molsberger A, Endres HG. Long-term improvement in pain coping for cLBP and gonarthrosis patients following body needle acupuncture: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Med Res. 2005;10:263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung A, Khadivi B, Duann JR, Cho ZH, Yaksh T. The effect of Ting point (tendinomuscular meridians) electroacupuncture on thermal pain: a model for studying the neuronal mechanism of acupuncture analgesia. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:653–661. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wang C, Mak AF, Chow DH. Effects of acupuncture on heart rate variability in normal subjects under fatigue and non-fatigue state. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;94:633–640. doi: 10.1007/s00421-005-1362-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lijue Z. Acupuncture and Chinese patent drugs for treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:99–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Li X, Han J, Leng J. Electro-acupuncture treatment for the upper segment ureterolithiasis under B-ultrasonography. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YC, Ly H, Golianu B. Acupuncture pain management for patients with cystic fibrosis: a pilot study. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:151–156. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05002758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde K, Streng A, Jurgens S, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes MG, Weidenhammer W, Willich SN, Melchart D. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2118–2125. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde M, Fjell A, Carlsson J, Dahlof C. Role of the needling per se in acupuncture as prophylaxis for menstrually related migraine: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchart D, Streng A, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes M, Hummelsberger J, Irnich D, Weidenhammer W, Willich SN, Linde K. Acupuncture in patients with tension-type headache: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331:376–382. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38512.405440.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra MN, Pullani AJ, Mohamed ZU. Prevention of PONV by acustimulation with capsicum plaster is comparable to ondansetron after middle ear surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:485–489. doi: 10.1007/BF03016527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedstrand E, Wijma K, Wyon Y, Hammar M. Vasomotor symptoms decrease in women with breast cancer randomized to treatment with applied relaxation or electro-acupuncture: a preliminary study. Climacteric. 2005;8:243–250. doi: 10.1080/13697130500118050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri I, Allais G, Schiapparelli P, Blasi I, Benedetto C, Facchinetti F. Acupuncture versus pharmacological approach to reduce Hyperemesis gravidarum discomfort. Minerva Ginecol. 2005;57:471–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata A, Sugenoya J, Nishimura N, Matsumoto T. Low and high frequency acupuncture stimulation inhibits mental stress-induced sweating in humans via different mechanisms. Auton Neurosci. 2005;118:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariente J, White P, Frackowiak RS, Lewith G. Expectancy and belief modulate the neuronal substrates of pain treated by acupuncture. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HJ, Kim ST, Yoon DH, Jin SH, Lee SJ, Lee HJ, Lim S. The association between the DRD2 TaqI A polymorphism and smoking cessation in response to acupuncture in Koreans. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:401–405. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Park H, Lee H, Lim S, Ahn K, Lee H. Deqi sensation between the acupuncture-experienced and the naive: a Korean study II. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:329–337. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X0500293X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, White AR, James MA, Hemsley AG, Johnson P, Chambers J, Ernst E. Acupuncture for subacute stroke rehabilitation: a Sham-controlled, subject- and assessor-blind, randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2026–2031. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish TB, Schaeffer A, Catanese M, Rogel MJ. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of real and sham acupuncture. Noninvasively measuring cortical activation from acupuncture. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2005;24:35–40. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2005.1411346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J, Strehler E, Noss U, Abt M, Piomboni P, Baccetti B, Sterzik K. Quantitative evaluation of spermatozoa ultrastructure after acupuncture treatment for idiopathic male infertility. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfab F, Hammes M, Backer M, Huss-Marp J, Athanasiadis GI, Tolle TR, Behrendt H, Ring J, Darsow U. Preventive effect of acupuncture on histamine-induced itch: a blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:1386–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohodenko-Chudakova IO. Acupuncture analgesia and its application in cranio-maxillofacial surgical procedures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quah-Smith JI, Tang WM, Russell J. Laser acupuncture for mild to moderate depression in a primary care setting – a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:103–111. doi: 10.1136/aim.23.3.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resim S, Gumusalan Y, Ekerbicer HC, Sahin MA, Sahinkanat T. Effectiveness of electro-acupuncture compared to sedo-analgesics in relieving pain during shockwave lithotripsy. Urol Res. 2005;33:285–290. doi: 10.1007/s00240-005-0473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe JA, Matteson SE, Morrow GR, Hickok JT, Bushunow P, Griggs J, Qazi R, Smith B, Kramer Z, Smith J. Acustimulation wrist bands are not effective for the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea in women with breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossberg E, Larsson PG, Birkeflet O, Soholt LE, Stavem K. Comparison of traditional Chinese acupuncture, minimal acupuncture at non-acupoints and conventional treatment for chronic sinusitis. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghaei M, Ahmadi A, Rezvani M. Clinical trial of nitroglycerin-induced controlled hypotension with or without acupoint electrical stimulation in microscopic middle ear surgery under general anesthesia with halothane. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2005;43:135–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg M, Larsson B, Lindberg LG, Gerdle B. Different patterns of blood flow response in the trapezius muscle following needle stimulation (acupuncture) between healthy subjects and patients with fibromyalgia and work-related trapezius myalgia. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Lowe B, Streitberger K. Perception of bodily sensation as a predictor of treatment response to acupuncture for postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:119–125. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siedentopf CM, Koppelstaetter F, Haala IA, Haid V, Rhomberg P, Ischebeck A, Buchberger W, Felber S, Schlager A, Golazsewski SM. Laser acupuncture induced specific cerebral cortical and subcortical activations in humans. Lasers Med Sci. 2005;20:68–73. doi: 10.1007/s10103-005-0340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Du Y, Yan L, Xia Y, Yan H, Han G, Guo Y, Shi X. Acupuncture for treatment of climacteric syndrome – a report of 35 cases. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Tong HC. Manual acupuncture for analgesia during electromyography: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1741–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Ratcliffe J, Thorpe L, Brazier J, Campbell M, Fitter M, Roman M, Walters S, Nicholl JP. Longer term clinical and economic benefits of offering acupuncture care to patients with chronic low back pain. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9:iii–x, 1. doi: 10.3310/hta9320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda Y, Hayashi K, Kuriowa K. The application of fMRI to basic experiments in acupuncture. The effects of stimulus points and content on cerebral activities and responses. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2005;24:47–51. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2005.1411348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usichenko TI, Dinse M, Hermsen M, Witstruck T, Pavlovic D, Lehmann C. Auricular acupuncture for pain relief after total hip arthroplasty – a randomized controlled study. Pain. 2005;114:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne PM, Krebs DE, Macklin EA, Schnyer R, Kaptchuk TJ, Parker SW, Scarborough DM, McGibbon CA, Schaechter JD. Acupuncture for upper-extremity rehabilitation in chronic stroke: a randomized sham-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:2248–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.07.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt C, Brinkhaus B, Jena S, Linde K, Streng A, Wagenpfeil S, Hummelsberger J, Walther HU, Melchart D, Willich SN. Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:136–143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi G, Xiuyun W, Tangping X, Zhihua D, Yunchen L. Effect of blood-letting puncture at twelve well-points of hand on consciousness and heart rate in patients with apoplexy. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Z, Zhenhui Y. Ulcerative colitis treated by acupuncture at Jiaji points (EX-B2) and tapping with plum-blossom needle at Sanjiaoshu (BL22) and Dachangshu (BL 25) – a report of 43 cases. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:83–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou D, Chen WH, Iwakiri K, Rigda R, Tippett M, Holloway RH. Inhibition of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations by electrical acupoint stimulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G197–G201. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00023.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor J, Bensky D. Acupuncture, a comprehensive text. Chicago: Eastland Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Zhang GP, Song SJ, Ding MP, Zhou JF, Bie XD, Liu JR, Zhang Y, Li ZH, Gao HF, Liu GG, Fei LT. [Clinical study on Zhuyu Tongfu serial recipe combined with acupuncture and massotherapy in treating hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage.] Chin J Integr Med. 2005;11:167–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02836498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai XS, Huang Y. [A comparative study on the acupoints of specialty of Baihui, Shuigou and Shenmen in treating vascular dementia.] Chin J Integr Med. 2005;11:161–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02836497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong ES, Deng MY, Cheng LH, Zhou S, Wang B, Zhang A, Li Y, Wang H. [Effect of vertebral manipulation therapy on vertebro-basilar artery blood flow in cervical spondylosis of vertebral artery type] Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2005;25:742–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XA, Zhu JS. [Clinical observation on hailong juanxiao recipe combined with kechuanping mounting on yongquan acupoint in treating children' bronchial asthma in the stage of attack] Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2005;25:738–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RY. [Clinical observation on treatment of cerebral infarction by combined therapy of acupuncture with extremities tissue separating manipulation] Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2005;25:496–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HT, Liu JH. [Clinical observation on treatment of peripheral facial paralysis with acupuncture and pricking-cupping therapy] Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2005;3:18, 69. doi: 10.3736/jcim20050106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SY, Jung HM. [The effects of abdominal meridian massage on constipation among CVA patients] Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2005;35:135–142. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2005.35.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]