Abstract

Geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins cause enhanced susceptibility, characterized primarily by an increase in viral infectivity, when expressed in transgenic plants. Here, we present genetic and biochemical evidence that enhanced susceptibility is attributable to the interaction of AL2 and L2 with SNF1 kinase, a global regulator of metabolism. Specifically, we show that AL2 and L2 inactivate SNF1 in vitro and in vivo. We further demonstrate that expression of an antisense SNF1 transgene in Nicotiana benthamiana plants causes enhanced susceptibility similar to that conditioned by the AL2 and L2 transgenes, whereas SNF1 overexpression leads to enhanced resistance. Transgenic plants expressing an AL2 protein that lacks a significant portion of the SNF1 interaction domain do not display enhanced susceptibility. Together, these observations suggest that the metabolic alterations mediated by SNF1 are a component of innate antiviral defenses and that SNF1 inactivation by AL2 and L2 is a counterdefensive measure. They also indicate that geminiviruses are able to modify host metabolism to their own advantage, and they provide a molecular link between metabolic status and inherent susceptibility to viral pathogens.

INTRODUCTION

Plants have evolved a variety of mechanisms that allow them to respond to virus challenge. Some responses, such as those mediated by salicylic acid or involving gene silencing, are the subjects of intense study, and the molecular details of how they act to limit virus replication or spread in the host are beginning to emerge. By contrast, the role of metabolic responses in defense against pathogens has received comparatively little attention, despite circumstantial evidence supporting a connection between metabolic status and resistance states. For example, it has long been known that defense gene activation is correlated with high levels of soluble sugars (Johnson and Ryan, 1990; Tsukaya et al., 1991) and that invertase mRNA levels increase rapidly after pathogen inoculation (Sturm and Chrispeels, 1990). Furthermore, the overexpression of yeast invertase in transgenic tobacco has been shown to induce a condition that resembles systemic acquired resistance (Herbers et al., 1996). Considering the potential importance of glucose and sucrose as signaling molecules in plants and other organisms (Jang and Sheen, 1997), these and other observations suggest that the alteration of metabolism may be an aspect of innate host defense.

SNF1 (SUCROSE NONFERMENTING1) was identified initially in yeast as a protein kinase required for the expression of invertase and other glucose-repressed genes (Celenza and Carlson, 1986). Subsequent studies have shown that SNF1 in yeast and plants, and the mammalian homolog AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), play a central role in the regulation of metabolism (for review, see Halford and Hardie, 1998; Hardie et al., 1998; Johnston, 1999). In response to nutritional and environmental stresses that deplete ATP, these Ser/Thr kinases turn off energy-consuming biosynthetic pathways and turn on alternative ATP-generating systems. In plants, for example, SNF1 can phosphorylate and inactivate key enzymes that control steroid and isoprenoid synthesis, nitrogen assimilation for amino acid and nucleotide synthesis, and sucrose synthesis (Sugden et al., 1999b). In yeast, SNF1 indirectly activates glucose-repressed genes (such as invertase) by altering the activity of transcriptional repressors and activators and also is capable of modulating the activity of RNA polymerase II holoenzyme by phosphorylating its C-terminal domain (Kuchin et al., 2000). That plant SNF1 kinase can complement yeast snf1 mutants indicates highly conserved function. Thus, members of the SNF1/AMPK family act in a similar and global manner to appropriately regulate metabolism in response to stress. Because virus replication constitutes a cellular stress, it is reasonable to suppose that SNF1/AMPK-mediated responses might be a component of the host response to infection. However, to our knowledge, this idea has not been investigated previously.

The geminiviruses are a family of single-stranded DNA viruses that infect a broad range of plant species and cause considerable losses of food and fiber crops. These relatively simple pathogens amplify their genomes in the nuclei of host cells by a rolling circle replication mechanism that uses double-stranded DNA intermediates as replication and transcription templates (for review, see Bisaro, 1996; Gutierrez, 1999; Hanley-Bowdoin et al., 1999). Because of their extensive reliance on host biosynthetic machinery, geminiviruses have been studied extensively as model systems for fundamental processes in plant cells, and much has been learned about virus replication and transcription. By contrast, the molecular mechanisms of viral pathogenesis are largely unknown.

We recently showed that proteins from two different geminiviruses, AL2 from Tomato golden mosaic virus (TGMV; genus Begomovirus) and L2 from Beet curly top virus (BCTV; genus Curtovirus) are pathogenicity determinants (Sunter et al., 2001). The product of the TGMV AL2 gene was first identified as a transcription factor required for the expression of late viral genes, including the coat protein gene (Sunter and Bisaro, 1992, 1997). The 15-kD AL2 (also called transcriptional activator protein) has a C-terminal activation domain, but unlike most transcription factors, it does not bind double-stranded DNA in a sequence-specific manner (Hartitz et al., 1999). The protein can be found in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments when expressed in insect and plant cells (van Wezel et al., 2001; our unpublished observations). The L2 gene occupies a position similar to that of AL2 in the BCTV genome. However, the 20-kD L2 protein shares only limited amino acid homology with AL2. It also lacks an obvious activation domain and is not required for coat protein gene expression (Stanley et al., 1992; Hormuzdi and Bisaro, 1995). Despite these differences, the two proteins share a common function in viral pathogenesis that does not involve transcriptional activation. When expressed constitutively from transgenes in Nicotiana benthamiana and N. tabacum plants, both truncated AL2 (lacking the activation domain) and full-length L2 condition a novel enhanced susceptibility phenotype. Specifically, TGMV, BCTV, and the unrelated, RNA-containing Tobacco mosaic virus exhibit greater infectivity on plants expressing the viral proteins than they do on nontransgenic control plants or plants expressing a nontranslatable version of AL2 (Sunter et al., 2001). Enhanced susceptibility is characterized by a reduction in mean latent period and a decrease in the inoculum concentration necessary to elicit infection of half of the plants (ID50), although disease symptoms and virus replication levels are not increased significantly.

To elucidate the mechanisms by which the viral proteins cause enhanced susceptibility, we searched for cellular proteins that interact with both AL2 and L2. Two proteins that met this criterion were identified from a yeast two-hybrid screen of an Arabidopsis cDNA library. One of them was adenosine kinase; the consequences of this interaction will be discussed in another report. The other protein was SNF1 kinase. Here, we present biochemical and genetic evidence that AL2 and L2 inactivate SNF1 and that the inactivation of SNF1 leads to enhanced susceptibility.

RESULTS

AL2 and L2 Interact with SNF1

Because TGMV AL2 and BCTV L2 proteins condition enhanced susceptibility when expressed in transgenic plants (Sunter et al., 2001), we were interested in identifying cellular proteins that interact with these different but related viral proteins. The yeast two-hybrid system (Fields and Song, 1989; Durfee et al., 1993) was used in a primary screen to search for proteins that interact with AL2. Using as bait GBD-AL21-83 (a fusion protein consisting of the GAL4 DNA binding domain and truncated AL2 lacking its C-terminal activation domain), a cDNA corresponding to SNF1 kinase was recovered from an Arabidopsis GAL4 activation domain fusion library (see Methods). BCTV L2 also was found to interact with SNF1, and interaction was observed when SNF1 was expressed as bait with full-length AL2 or L2 as prey (Table 1). AL2 and L2 also showed a relatively weak interaction with yeast SNF1 but not with any of a panel of negative control proteins, including lamin, CDK2, p53, and the TGMV BL1, BR1, and coat proteins (data not shown). Interestingly, both AL2 and L2 lack a consensus SNF1 phosphorylation site (Weekes et al., 1993), which suggested that the interactions were not simply a reflection of kinase-substrate relationships.

Table 1.

Regions of AL2 and L2 Required for Interaction with SNF1 in the Yeast Two-Hybrid System

| Bait | Prey | Interactiona |

|---|---|---|

| AL2 1-114 | SNF1 | ++ |

| AL2 1-83 | SNF1 | ++ |

| AL2 1-43 | SNF1 | ++ |

| AL2 1-32 | SNF1 | − |

| AL2 10-43 | SNF1 | ++ |

| AL2 20-43 | SNF1 | ++ |

| AL2 30-43 | SNF1 | ++ |

| AL2 36-43 | SNF1 | − |

| AL2 Δ33-43b | SNF1 | − |

| SNF1 | AL2 1-129 | ++ |

| SNF1 | AL2 Δ33-43c | + |

| SNF1 | L2 1-174 | ++ |

| L2 1-174 | SNF1 | ++ |

| L2 1-100 | SNF1 | ++ |

| L2 66-79 | SNF1 | ++ |

The indicated bait proteins were expressed as GAL4 DNA binding domain fusions, and the indicated prey proteins were expressed as GAL4 activation domain fusions in yeast Y190 cells (Durfee et al., 1993). All AL2 bait constructs lacked the activation domain, which was mapped previously to amino acids 115 to 129 (Hartitz et al., 1999).

Interaction was indicated by the ability of cells transformed with both bait and prey plasmids to grow on medium lacking His and containing 50 mM 3-aminotriazole. As an additional indicator of interaction, colonies were monitored for LacZ activity (blue color) using a filter-lift assay. Interaction symbols are as follows: −, no interaction; +, weak interaction, blue color developed after 2 h; ++, moderate to strong interaction, blue color developed within minutes to 2 h.

AL2 Δ33-43 expressed in a 1-83 background.

AL2 Δ33-43 expressed in a full-length (1-129) background.

The SNF1 cDNA obtained from the two-hybrid screen contained a complete open reading frame identical to one identified previously as Arabidopsis PROTEIN KINASE11 (AKIN11) (Bhalerao et al., 1999). AKIN11 is one of a small group of SNF1-related kinases (SnRKs) in Arabidopsis. It is placed in subfamily 1 (SnRK1) along with AKIN10 and kinases from other plant species that show the greatest homology with yeast SNF1 and AMPK (Le Guen et al., 1992; Halford and Hardie, 1998). Arabidopsis also contains genes for SnRK2- and SnRK3-type kinases that are considerably divergent from AKIN10 and AKIN11 (Chikano et al., 2001). AKIN10 and AKIN11, both 512 amino acids in length, display 89% amino acid identity in the N-terminal portion (1 to 343), which contains the kinase catalytic domain. Although there are numerous exchanges in the C-terminal third that contains the regulatory domain, amino acid identity in this region also is relatively high (64%). That both AKIN10 and AKIN11 are able to complement a yeast snf1 mutant suggests a similar function for these proteins (Bhalerao et al., 1999). For convenience, we refer to the AKIN11 protein identified in our screen as SNF1.

To approximately locate the domains of AL2 and L2 involved in SNF1 interaction, yeast two-hybrid assays using SNF1 and defined regions of the viral proteins were performed. These experiments showed that small conserved regions of AL2 (amino acids 30 to 43) and L2 (amino acids 66 to 79) are sufficient for interaction with SNF1, although other as yet unidentified sequences also appear to be involved (Table 1). The conserved region contains a putative zinc finger (Hartitz et al., 1999), and deletion of all or a portion of this region significantly reduced yeast two-hybrid interaction in a full-length (amino acids 1 to 129) AL2 background and abolished interaction in a truncated (amino acids 1 to 83) background.

Transgenic Plants Expressing Antisense SNF1 Show Enhanced Susceptibility to Geminivirus Infection

To examine the biological relevance of SNF1 to geminivirus infection, we created transgenic plants that contain an antisense SNF1 construct as a means of reducing its expression in vivo. N. benthamiana was selected over Arabidopsis for this study because it is an excellent host for TGMV and BCTV and because previous studies of enhanced susceptibility conditioned by AL2 and L2 transgenes were performed in this species. The high degree of homology between SnRK1 sequences in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana species, particularly within the kinase catalytic domain located in the N-terminal two-thirds of the protein, further suggested that a heterologous transgene would be effective. For example, amino acid identity in the N-terminal portions (1 to 343) of Arabidopsis SNF1 (AKIN11) and the Nicotiana homolog NPK5 (Muranaka et al., 1994) is 85%, and nucleotide sequence identity is 80% with several stretches of no or minimal mismatch.

Transgenic N. benthamiana plants containing antisense SNF1 under the control of the constitutive 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus were prepared by Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated transformation as described previously (Sunter and Bisaro, 1997). Several independent lines were established by self-fertilization of regenerated, transformed plants, and three of these lines (AS-4, AS-5, and AS-12) were selected for further analysis. The presence of the transgene in each of the lines was confirmed by PCR amplification of transgene sequences using primers complementary to flanking T-DNA (data not shown). Although transgenic plants were morphologically indistinguishable from nontransgenic plants, transgene expression was demonstrated by RNA gel blot hybridization. This analysis showed that plants from each line produced a transcript of the appropriate size and sense that was not found in wild-type nontransgenic plants (Figure 1A). Steady state levels of the 1.8-kb antisense transcript varied less than twofold between lines, with expression being greatest in line AS-12.

Figure 1.

Steady State Levels of SNF1-Related Transcripts in Transgenic Plants.

Total and poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from nontransgenic (NT) N. benthamiana plants or plants containing a sense (S-1, S-2, S-3, and S-5) or an antisense (AS-4, AS-5, and AS-12) SNF1 transgene (F2 generation). RNAs were subjected to gel blot hybridization using the indicated 32P-labeled probes. Blots were stripped and reprobed with ATPase sequences to provide a loading control. Autoradiograms are shown.

(A) Total RNA (10 μg per lane) hybridized with a probe specific for antisense SNF1 RNA.

(B) Poly(A)+ RNA (1 μg per lane) hybridized with a probe specific for sense SNF1 RNA.

(C) Sequences corresponding to SNF1 mRNA (derived from transgenes and/or endogenous genes) in nontransgenic N. benthamiana (Nb) and Arabidopsis (At) plants and plants from transgenic lines S-1, S-2, and AS-12 were detected in DNase-treated total RNA preparations by reverse transcriptase (RT)–mediated PCR. SNF1-specific products were identified subsequently by DNA gel blot analysis using a mixed probe consisting of sense and antisense SNF1 sequences. Similarly amplified rRNA products were detected by ethidium bromide staining. PCR using SNF1- and rRNA-specific primer sets produced the expected 478- and 315-bp fragments, respectively, with the exception of S-2 samples, in which the SNF1-specific product was absent. Similar results were obtained in three experiments with two independently obtained RNA preparations for each sample.

Both TGMV and BCTV were able to infect antisense SNF1 plants and elicited characteristic disease symptoms. Furthermore, the transgenic plants proved more susceptible to infection than wild-type nontransgenic plants, as judged by a reduction in the time to first appearance of symptoms (mean latent period). As shown in Table 2, plants expressing antisense SNF1 exhibited TGMV symptoms 1 to 2 days earlier than nontransgenic plants. Similarly, symptoms typical of BCTV infection appeared 3 to 5 days earlier on transgenic plants. Under the conditions of the test, TGMV showed an intrinsic latent period of 11 to 12 days on wild-type N. benthamiana plants, whereas the BCTV latent period was ∼20 days. Thus, mean latent periods on the transgenic hosts were reduced by ∼10 to 16% for TGMV and by 13 to 27% for BCTV, and analysis of the data by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's test confirmed that the reductions were statistically significant in all cases. Similar reductions in mean latent period (12 to 31%), also without enhancement of disease symptoms, were observed previously after TGMV and BCTV inoculation of transgenic N. benthamiana plants expressing TGMV AL21-100 or BCTV L2 proteins (Sunter et al., 2001). It also should be noted that although agroinoculation was used exclusively to deliver viral DNA in the studies reported here, the earlier study included agroinoculation and standard mechanical inoculation experiments with purified viral DNA (TGMV and BCTV) and purified virions (Tobacco mosaic virus) (Sunter et al., 2001). The results of that study clearly demonstrated that mean latent period reduction was independent of the inoculation method used.

Table 2.

Mean Latent Period after TGMV and BCTV Inoculation of N. benthamiana Plants Expressing an Antisense SNF1 Construct

|

N. benthamiana

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Nontransgenic | AS-4 | AS-5 | AS-12 |

| TGMV | 11.6 ± 0.5 a (37/48) |

9.7 ± 0.3 b (48/48) |

10.4 ± 0.5 b (33/33) |

10.3 ± 0.4 b (46/46) |

| BCTV | 20.4 ± 0.5 g (58/121) |

17.0 ± 0.5 h (75/79) |

17.7 ± 0.6 h (70/81) |

14.8 ± 0.4 h (57/61) |

Transgenic plants (F2 generation) expressing an antisense SNF1 transgene were agroinoculated using a mixture of Agrobacterium cells containing Ti plasmids harboring 1.5 copies of the TGMV A or B genome component (OD600 = 1.0 for each component) or with cells containing a Ti plasmid harboring a tandem dimer of the BCTV genome (OD600 = 1.0), as described in Methods. Plants were scored for the appearance of systemic symptoms typical of TGMV or BCTV infection. The significance of mean latent period differences observed between transgenic plants and nontransgenic plants (days after inoculation ± SE) was confirmed by one-way analysis of variance (P < 0.01 for agroinoculations). Lowercase letters indicate means that are significantly different from the nontransgenic control mean (P < 0.01) as determined by Dunnett's test. Numbers in parentheses indicate infectivity (number of plants infected/number of plants inoculated). The data are averages of two and four independent experiments with TGMV and three independent experiments with BCTV. Experiments included 14 to 32 plants per treatment.

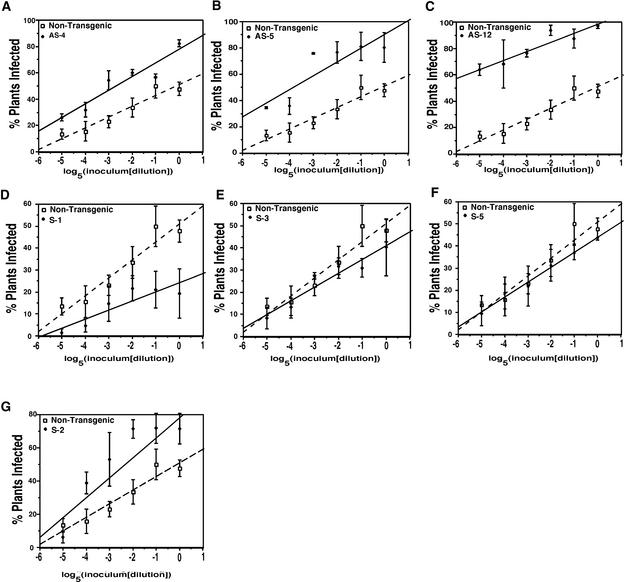

To further characterize the phenotype, the ID50 in samples of transgenic antisense SNF1 plants and nontransgenic control plants was determined. BCTV, which has a monopartite genome, was chosen over the bipartite TGMV for this study because BCTV infectivity follows simple one-hit kinetics. To perform these measurements, BCTV was agroinoculated to groups of plants beginning with a standard dose of ∼3 × 107 Agrobacterium cells per plant (30 μL of culture at OD600 = 1.0) (Sunter et al., 2001). Additional groups of plants were inoculated with serial fivefold dilutions of the standard dose. As illustrated in Figures 2A to 2C, the BCTV ID50 on antisense SNF1 plants was considerably less than that on nontransgenic plants. Approximately 50% of nontransgenic plants became infected with the standard inoculum dose, whereas a similar level of infectivity was achieved after a 60-fold dilution of the inoculum with line AS-4 and after a >300-fold dilution with line AS-5. In the case of line AS-12, infectivity of >50% was observed even at the lowest inoculum dose tested (3125-fold dilution). These reductions in BCTV ID50 are similar to, albeit somewhat greater than, those observed in transgenic plants expressing AL21-100. In plants from three transgenic lines expressing the viral protein, 50% infection was achieved at 25- to 250-fold dilution of the standard dose (Sunter et al., 2001).

Figure 2.

BCTV ID50 on Nontransgenic Plants and Transgenic Plants Containing Antisense and Sense SNF1 Transgenes.

N. benthamiana plants were agroinoculated with BCTV using a standard dose (OD600 = 1.0) or serial fivefold dilutions of the standard dose. The fraction of infected plants in each sample was plotted versus the log5 of the dilution, and the BCTV ID50 was calculated as the inoculum dose at which 50% of the plants in the sample became infected. Broken lines indicate dilution curves for nontransgenic plants. Values shown represent averages of at least three independent experiments, with 16 plants for each inoculum dose in each experiment.

(A) to (C) Nontransgenic plants and plants from transgenic lines expressing antisense SNF1 (lines AS-4, AS-5, and AS-12).

(D) to (F) Nontransgenic plants and plants from transgenic lines expressing sense SNF1 (lines S-1, S-3, and S-5).

(G) Nontransgenic plants and plants from transgenic line S-2 exhibiting cosuppression of a sense SNF transgene and the endogenous SNF1 gene.

It was concluded from these experiments that expression of an antisense SNF1 transgene in N. benthamiana plants results in enhanced susceptibility to infection by TGMV and BCTV, as measured by a decrease in mean latent period and by a decrease in the amount of virus inoculum required to infect the transgenic plants. However, enhancement of disease symptoms was not observed; once transgenic plants became infected, the infections proceeded with normal kinetics and produced symptoms typical of TGMV or BCTV infection. Because similar decreases in mean latent period and ID50, without enhancement of disease symptoms or virus load, were observed previously in N. benthamiana plants expressing AL21-100 and L2 (Sunter et al., 2001), we further concluded that the expression of antisense SNF1 phenocopies the expression of the viral proteins.

Constitutive Expression of a Sense SNF1 Transgene Results in Enhanced Resistance to Geminivirus Infection

Because the expression of antisense SNF1 leads to enhanced susceptibility, we next asked whether the constitutive expression of a sense SNF1 transgene might have the opposite effect. It proved difficult to generate transgenic N. benthamiana plants containing the sense SNF1 coding sequence under the control of the 35S promoter. Only six lines were obtained, and two of these (S-4 and S-6) had poor seed set and were not studied further. Plants from the remaining lines, with the notable exception of line S-2, grew more slowly and were smaller than wild-type nontransgenic plants. The S-2 plants were indistinguishable from the nontransgenic plants. The presence of the transgene in each of the lines was confirmed by PCR amplification of transgene sequences using primers complementary to flanking T-DNA (data not shown).

As shown in Figure 1B, gel blot hybridization analysis of poly(A)+ RNA from transgenic plants showed that lines S-1, S-3, and S-5 contained approximately equivalent amounts of the expected 1.8-kb transgene transcript, which was not present in nontransgenic plants. However, a signal was not detected in extracts from line S-2. It also proved difficult to detect endogenous SNF1 transcripts (expected size of 2.1 kb) by gel blot analysis in either N. benthamiana (Figure 1B) or Arabidopsis (data not shown), suggesting that they are present in low abundance relative to the transgene transcript. To observe the endogenous mRNAs, reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR was performed using primers designed to amplify a 478-bp fragment (nucleotides 684 to 1162) from the coding region of AKIN11 SNF1 mRNA. Unlike the SNF1 probes used in gel blot analysis, which should detect both AKIN10- and AKIN11-related transcripts in Arabidopsis, the PCR primers were expected to be specific for AKIN11 mRNA. DNA gel blot hybridization of PCR products revealed the presence of endogenous SNF1 transcripts in nontransgenic N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis as well as transcripts that could be derived from both the endogenous gene and the transgene in plants from lines S-1 and AS-12 (Figure 1C). However, there still was no evidence for either transgene-derived or endogenous SNF1 mRNA in line S-2. The simplest interpretation of this result is that both the SNF1 transgene and its endogenous counterpart are silenced, presumably by cosuppression, in line S-2. Cosuppression in this case could operate either at the transcriptional or the post-transcriptional level.

To examine the susceptibility of sense SNF1 plants, the ID50 for BCTV was determined for each line as described above. As illustrated in Figures 2D to 2F, lines S-1, S-3, and S-5 proved somewhat more resistant to infection than nontransgenic plants. In these lines, infectivity did not reach 50% even at the beginning, standard inoculum dose. By contrast, plants from line S-2 exhibited an enhanced susceptibility phenotype similar to that of antisense SNF1 plants (lines AS-4, AS-5, and AS-12; Figures 2A to 2C). In line S-2, 50% infection was achieved after a 60-fold dilution of the standard dose, whereas undiluted inoculum was required to elicit infection in 50% of nontransgenic plants (Figure 2G). As was the case in antisense lines, infections once initiated progressed normally in all sense lines (including S-2), and infected plants displayed characteristic disease symptoms with no evidence of reduced (or increased) severity.

From these experiments, we concluded that constitutive expression of a SNF1 transgene leads to enhanced resistance, although at the cost of adverse effects on plant growth. In addition, the correlation between SNF1 cosuppression and greater virus susceptibility observed in line S-2 reinforces our previous conclusion that reducing SNF1 expression results in enhanced susceptibility.

Transgenic Plants Expressing SNF1 Interaction–Defective AL2 Do Not Exhibit Enhanced Susceptibility

We previously showed that expression of AL21-100 (which lacks the activation domain) in transgenic N. benthamiana plants results in enhanced susceptibility (Sunter et al., 2001). To ascertain whether this phenotype depends on the ability of AL2 to interact with SNF1, we tested plants that express a SNF1 interaction–defective version of AL2.

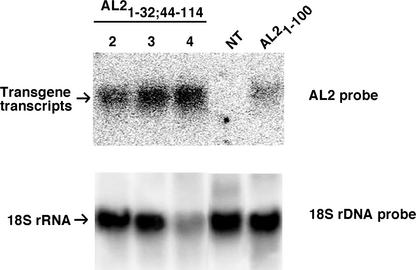

Several independent N. benthamiana lines containing an AL21-32;44-114 transgene (AL2 Δ33-43 in a 1-114 background) under the control of the 35S promoter were generated. This transgene is expected to produce an AL2 protein that lacks the activation domain (amino acids 115 to 129) and has a reduced ability to interact with SNF1 as a result of the deletion of residues 33 to 43 (Table 1). Three transgenic lines (4259-2, 4259-3, and 4259-4) were selected for further analysis. Plants from these lines were similar in appearance to nontransgenic plants and showed no obvious growth or developmental defects. Each contained the transgene, as demonstrated by PCR amplification of sequences between the flanking T-DNAs (data not shown). As shown in Figure 3, plants from each line also produced an AL2-specific transcript similar in size to transcripts found in AL21-100 plants. Transgene expression in line 4259-4 was approximately threefold greater than that in lines 4259-2 and 4259-3.

Figure 3.

AL2-Related Transcripts in Transgenic Plants.

Total RNA was isolated from nontransgenic (NT) N. benthamiana plants, plants containing an AL21-100 transgene (line 472-7) (Sunter et al., 2001), or plants containing an AL21-32;44-114 transgene (lines 4259-2, 4259-3, and 4259-4). RNA samples (10 μg per lane) were subjected to gel blot hybridization with a 32P-labeled AL2-specific probe. Blots were stripped subsequently and reprobed with labeled 18S rRNA sequences to provide loading controls.

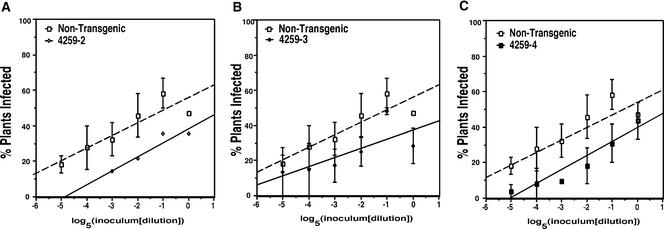

The BCTV ID50 for each of the lines was determined as described above. BCTV was able to infect the transgenic plants and produced characteristic disease symptoms. However, unlike plants expressing AL21-100 (Sunter et al., 2001), lines expressing AL21-32;44-114 showed no evidence of enhanced susceptibility (Figures 4A to 4C). Instead, the plants were more difficult to infect than nontransgenic plants, and 50% infectivity was not achieved with the undiluted inoculum dose in any of the transgenic lines. The basis for this enhanced resistance is unknown, but it is possibly attributable to a dominant negative effect of the mutant AL2 gene product on BCTV replication. In any event, it is clear that the removal of amino acids involved in SNF1 interaction (in this case, amino acids 33 to 43) from AL2 renders it unable to confer enhanced susceptibility.

Figure 4.

BCTV ID50 on Nontransgenic Plants and Transgenic Plants Containing an AL21-32;44-114 Transgene.

N. benthamiana plants were agroinoculated with BCTV using a standard dose (OD600 = 1.0) or serial fivefold dilutions of the standard dose. The fraction of infected plants in each sample was plotted versus the log5 of the dilution. The ID50 is the inoculum dose at which 50% of the plants in the sample became infected. Broken lines indicate dilution curves for nontransgenic plants. Values shown are from one experiment (line 4259-2) or represent averages of two independent experiments (lines 4259-3 and 4259-4), with 16 plants for each inoculum dose in each experiment.

(A) Nontransgenic plants and plants from AL21-32;44-114 line 4259-2.

(B) Nontransgenic plants and plants from AL21-32;44-114 line 4259-3.

(C) Nontransgenic plants and plants from AL21-32;44-114 line 4259-4.

AL2 and L2 Inhibit SNF1 Kinase Activity in Vitro

The correlation between the reduction of SNF1 expression and the enhanced susceptibility phenotype led us to hypothesize that the interaction of AL2 and L2 with SNF1 results in the inhibition of SNF1 kinase activity rather than the phosphorylation of the viral proteins. To test this hypothesis, the functional consequences of the interactions were examined in vitro.

To obtain the proteins necessary to perform these experiments, full-length SNF1 and the SNF1 kinase domain (amino acids 1 to 342) were expressed as six-His fusion proteins in insect cells using baculovirus vectors (see Methods). However, because the full-length protein proved difficult to solubilize, further work was performed with the kinase domain polypeptide (SNF1-KD). As a control, a His-tagged kinase domain mutant protein containing a substitution in the ATP binding site (K49R) also was expressed in insect cells. The comparable K84R substitution abolishes activity in the yeast enzyme (Celenza and Carlson, 1989). Both SNF1-KD and SNF1-KD K49R were purified partially by nickel-agarose chromatography and were the only species visible after PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of protein preparations (data not shown). The viral proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells and partially purified as described previously (Hartitz et al., 1999). AL2 was expressed as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein, and L2 was expressed as a His fusion protein. AL2 Δ33-43 (constructed in the full-length AL2 1-129 background), which has a reduced ability to interact with SNF1 (Table 1), also was expressed as a GST fusion protein.

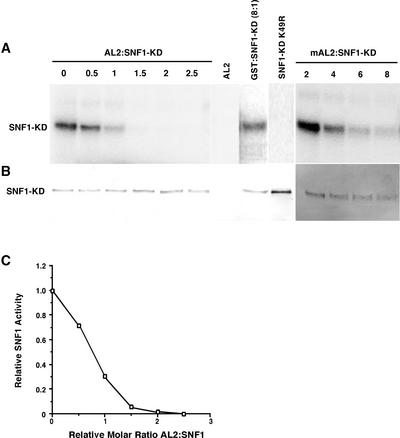

As shown in Figure 5, SNF1-KD displayed considerable autophosphorylation activity when incubated under standard assay conditions in the presence of γ-32P-ATP. That SNF1-KD K49R was not phosphorylated under the same conditions confirmed that all activity observed in SNF1-KD preparations was caused by autophosphorylation. Remarkably, the addition of AL2 protein to kinase assays resulted in a drastic reduction of SNF1-KD activity, with nearly complete inhibition observed at a 2:1 molar ratio of AL2 to SNF1-KD. By contrast, an eightfold molar excess of the similarly prepared, negative control protein GST had no effect on kinase activity. The ability of AL2 to inhibit SNF1-KD is dependent on its ability to interact with the kinase, because when AL2 Δ33-43 (mAL2) was added to kinase reactions, inhibition was observed but at a reduced level. In this case, some activity remained even after the addition of an eightfold molar excess of the mutant viral protein (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

TGMV AL2 Protein Inhibits SNF1 Kinase Activity in Vitro.

Autophosphorylation activity of the His-tagged SNF1 kinase domain (SNF1-KD) was assayed as described in Methods and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

(A) Autoradiograph of a gel blot membrane showing the products of reactions containing either SNF1-KD alone (0) or SNF1-KD with varying molar ratios of GST-AL2 (0.5- to 2.5-fold excess of AL2) or an 8-fold excess of the negative control protein GST. Other control reactions contained GST-AL2 alone or His-tagged SNF1-KD K49R. In similar experiments, reactions contained SNF1-KD with varying molar ratios of GST-mAL2 (2-fold to 8-fold excess of mAL2). mAL2 indicates a mutant AL2 protein (AL2 Δ33-43) containing an internal deletion of the SNF1 interaction domain.

(B) Immunoblot of the same gel blot membrane shown in (A) probed with anti-His antibody.

(C) Graph showing relative SNF1-KD activities plotted against increasing AL2:SNF1-KD molar ratios. SNF1 activity was quantitated using a phosphorimager.

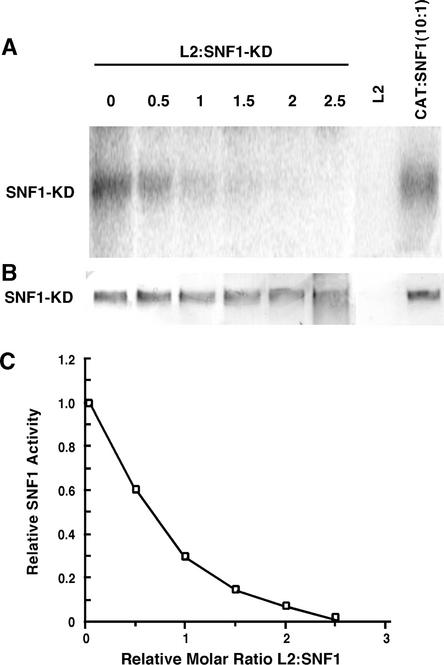

Inhibition of SNF1-KD activity also occurred when L2 was added to kinase assays. In the case of the BCTV protein, nearly complete inhibition of SNF1-KD was obtained at a molar ratio of ∼2.5:1 (Figure 6). No inhibition of SNF1-KD activity was evident after the addition of a 10-fold molar excess of an appropriate negative control protein, His-tagged chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT).

Figure 6.

BCTV L2 Protein Inhibits SNF1 Kinase Activity in Vitro.

Autophosphorylation activity of the His-tagged SNF1 kinase domain (SNF1-KD) was assayed as described in Methods and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

(A) Autoradiograph of a gel blot membrane showing the products of reactions containing either SNF1-KD alone (0) or SNF1-KD with varying molar ratios of His-tagged L2 (0.5- to 2.5-fold excess of L2) or a 10-fold excess of the negative control protein CAT.

(B) Immunoblot of the same gel blot membrane shown in (A) probed with anti-His antibody. To simplify the image, signals corresponding to His-tagged L2 are not shown.

(C) Graph showing relative SNF1-KD activities plotted against increasing L2:SNF1-KD molar ratios. SNF1 activity was quantitated using a phosphorimager.

We conclude from these experiments that the viral proteins AL2 and L2 are not phosphorylated by SNF1. Rather, the consequence of AL2 and L2 interaction with SNF1-KD is the inhibition of kinase activity, with AL2 and L2 inhibiting the kinase to a comparable extent in the assays described here. The inhibition requires direct interaction between the viral proteins and the kinase.

L2 Inhibits SNF1 Activity in Vivo

As an additional confirmation of functional interaction, we investigated whether L2 can inhibit SNF1 kinase activity in yeast cells. The L2 protein was chosen over AL2 for this study because full-length AL2 can cause slow growth and small colony size when expressed in yeast (Hartitz et al., 1999). In initial experiments, transfection of wild-type yeast with plasmids capable of expressing L2 had no effect on the ability of cells to grow on medium containing glycerol or sucrose as a carbon source, suggesting that the weak interaction between L2 and yeast SNF1 was insufficient to result in a significant inhibition of endogenous kinase activity (data not shown).

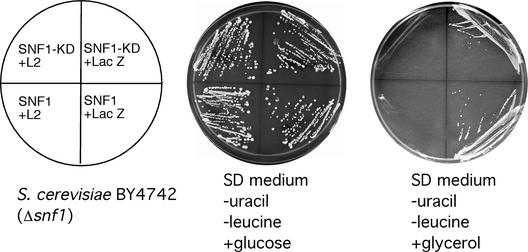

In subsequent experiments, we took advantage of the ability of SNF1 from plants to complement yeast snf1 mutants. We first confirmed that both Arabidopsis SNF1 and SNF1-KD can complement a yeast snf1 deletion strain that by itself cannot grow on medium containing a carbon source other than glucose. As illustrated in Figure 7, when plasmids expressing either SNF1 or SNF1-KD were introduced into the deletion strain, complementation occurred, as indicated by the growth of the cells on glycerol-containing medium. Complementation is a clear indication of the presence of functional SNF1 and SNF1-KD, and the activity of these proteins was unaffected by coexpression of the negative control protein LacZ. However, when the snf1 deletion strain was cotransfected with an expression plasmid containing SNF1 or SNF1-KD and a plasmid expressing L2, complementation was abolished and cells lost the ability to grow on glycerol-containing medium (Figure 7). L2 expression did not inhibit the growth of the same cells on control plates containing glucose.

Figure 7.

BCTV L2 Protein Abolishes SNF1 Complementation in Yeast.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain BY4742 (Δsnf1) was transformed with plasmids expressing the indicated proteins and streaked on synthetic defined (SD) medium containing either glucose or glycerol as a carbon source. The absence of uracil and Leu in the medium ensured the maintenance of the expression plasmids. In the experiment shown, SNF1 and SNF1-KD were expressed from a low-copy vector (YCpL), whereas L2 was expressed from a high-copy vector (YEpU). However, similar results were obtained when both SNF1-KD and L2 were expressed from high-copy vectors (YEpL and YEpU, respectively; data not shown).

In a follow-up experiment, cells from the snf1 deletion strain were cotransfected with the SNF1 and L2 expression plasmids and plated on synthetic defined (SD) medium containing glucose but lacking Leu and uracil. These conditions allow cells to survive without SNF1 activity while demanding the presence of both the SNF1 (Leu+) and L2 (uracil+) expression plasmids. Six transformants (three colonies chosen at random from each of two independent transformations) were streaked individually onto selective medium, which demands SNF1 activity but does not require maintenance of the L2 expression plasmid (SD + glycerol − Leu + uracil). Six colonies were taken from these SNF1 selection plates and replica plated onto SD + glucose − Leu + uracil or SD + glucose + Leu − uracil. All colonies had lost the L2 expression plasmid, as indicated by the inability of cells to grow after transfer to medium lacking uracil. As expected, all colonies maintained the SNF1 expression plasmid and were able to grow on medium lacking Leu (data not shown). Thus, complementation of the yeast SNF1 deletion strain by Arabidopsis SNF1 was observed only in the absence of L2.

Together, these experiments demonstrate that L2 inhibits Arabidopsis SNF1 and SNF1-KD activity when expressed with these kinase polypeptides in yeast cells and provide direct evidence for functional L2–SNF1 interaction in vivo.

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we demonstrated that the TGMV AL2 and BCTV L2 proteins condition an enhanced susceptibility phenotype when expressed in transgenic plants, as measured by a decrease in mean latent period and reduced ID50 after inoculation of plants with the cognate geminiviruses or with the unrelated Tobacco mosaic virus (Sunter et al., 2001). In this report, we extend these findings by showing that AL2 and L2 interact with Arabidopsis SNF1 kinase and that an interaction domain maps to a conserved region of the functionally related viral proteins, which otherwise show rather weak amino acid homology. Removal of this conserved region from AL2 significantly reduces its ability to interact with SNF1 and abolishes its ability to condition enhanced susceptibility in transgenic plants. Furthermore, we demonstrate that reducing SNF1 expression in plants, either through the action of an antisense SNF1 transgene or by cosuppression after introduction of a sense SNF1 transgene, reproduces the enhanced susceptibility phenotype. Conversely, constitutive overexpression of SNF1 from a sense transgene leads to enhanced resistance, a condition in which a greater inoculum concentration is required to elicit an infection. Based on these observations, we developed the hypothesis that AL2 and L2 cause enhanced susceptibility by interacting with SNF1 kinase and inhibiting its activity. Two additional lines of evidence are presented in support of this hypothesis. First, using recombinant proteins, we demonstrate that AL2 and L2 inhibit autophosphorylation of SNF1-KD in vitro. Inhibition is nearly stoichiometric and correlates with the ability of the viral protein to interact with SNF1. Second, we show that complementation of a yeast snf1 deletion strain by Arabidopsis SNF1 and SNF1-KD is blocked by coexpression of L2, directly demonstrating that a functional interaction resulting in SNF1 inhibition occurs in vivo.

Kinases of the SNF1/AMPK family are recognized as key regulators of metabolism and have been described as the “fuel gauge” of the cell (Halford and Hardie, 1998; Hardie et al., 1998; Johnston, 1999). The responses to nutritional and environmental stress (termed the cellular stress response) mediated by SNF1/AMPK include the shut down of biosynthetic pathways and the activation of alternative, energy-generating pathways. SNF1/AMPK inhibits biosynthetic pathways by phosphorylating and inactivating key regulatory enzymes such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which catalyzes the committed step in fatty acid synthesis. In addition, SNF1 kinase activities from spinach leaves have been shown in vitro to phosphorylate and inactivate 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase, nitrate reductase, and sucrose phosphate synthase (Sugden et al., 1999b). Thus, activated SNF1 appears to negatively regulate several biosynthetic pathways in plants, including fatty acid synthesis, steroid and isoprenoid synthesis, nitrogen assimilation for the synthesis of nucleotides and amino acids, and sucrose synthesis.

Perhaps the best example of the activation of alternative catabolic pathways is found in yeast, in which SNF1 is essential for the expression of glucose-repressed genes (e.g., invertase) in response to the nutritional stress of glucose limitation. Yeast SNF1 is known to phosphorylate and inactivate transcriptional repressors (e.g., Mig-1), regulate transcriptional activators (e.g., CAT8), and directly modulate RNA polymerase II holoenzyme (Carlson, 1999; Kuchin et al., 2000). That SNF1 kinase from several plant sources can complement yeast snf1 mutants indicates that SNF1-mediated responses are highly conserved and suggests that the plant kinases also can modulate transcription. In addition, the interaction of SNF1 with the kinase inhibitor PRL1 suggests a pleiotropic role in the regulation of metabolic, hormonal, and stress responses in Arabidopsis (Németh et al., 1998; Bhalerao et al., 1999). The more recent discovery of SNF1 interactions with proteosome and ubiquitin ligase components further implies a role in the regulation of essential signaling pathways (Farrás et al., 2001).

That SNF1-mediated responses, or at least a subset of them, are antagonistic to virus infection is clear from the enhanced susceptibility observed when SNF1 expression is reduced in transgenic plants and from the enhanced resistance phenotype that results when SNF1 is overexpressed constitutively. Thus, metabolic responses mediated by SNF1 appear to be a component of plant innate defense systems, and we propose that the geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins counter this defense by inhibiting SNF1 kinase activity.

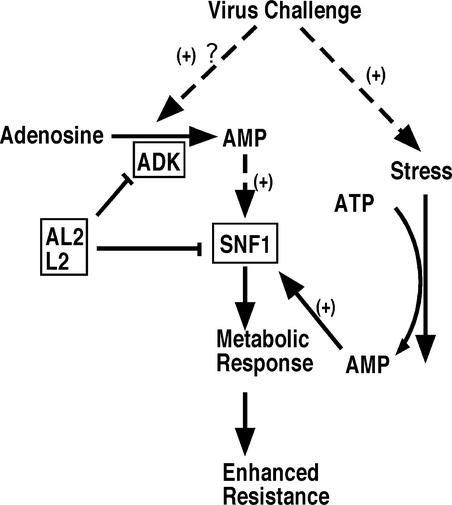

The available evidence indicates that the intracellular signal that activates SNF1/AMPK is the depletion of ATP, which is sensed as an increase in AMP:ATP ratio. In the case of plant SNF1 and mammalian AMPK, it is known that the kinases are directly bound and activated by 5′-AMP (Davies et al., 1995; Hawley et al., 1995; Sugden et al., 1999a). Thus, additional support for the idea that SNF1-mediated responses are targeted by AL2 and L2 comes from our recent finding that these same viral proteins also interact with and inactivate adenosine kinase (ADK), which phosphorylates adenosine to 5′-AMP (H. Wang, L. Hao, G. Sunter, and D.M. Bisaro, unpublished results). That AL2 and L2 interact with and inactivate both SNF1 and ADK underscores the importance of SNF1-mediated responses to host defense and suggests that geminiviruses have developed a dual approach to disabling SNF1 that involves both direct inhibition and inhibition of a potential (indirect) SNF1 activator, ADK. This finding further implies the existence of a signaling pathway that acts through ADK to stimulate SNF1 in response to virus challenge. Such a pathway might permit the more rapid activation of SNF1 than could occur otherwise if this activation depended solely on increasing AMP levels as a result of ATP depletion (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Inhibition of Stress Responses by AL2 and L2 Proteins.

The model proposes that SNF1-mediated metabolic (stress) responses lead to enhanced resistance and that the geminivirus proteins AL2 and L2 inhibit this pathway and cause enhanced susceptibility by inactivating SNF1 and ADK. This suggests that a portion of the AMP generated by ADK is involved in SNF1 activation and further implies the existence of a signaling pathway that operates through ADK to allow the rapid activation of SNF1. Virus challenge also could activate SNF1 through the established mechanism of ATP depletion. The importance of SNF1-mediated responses in antiviral defense is supported by our observation that transgenic plants expressing AL2, L2, or antisense SNF1 show enhanced susceptibility to virus infection.

Exactly how SNF1-mediated metabolic responses lead to enhanced resistance is unclear. However, because their primary effect is at the level of infectivity, we speculate that stress responses act to limit virus replication in initially infected cells, thereby reducing the probability of spread to neighboring cells in numbers sufficient to establish a systemic infection. However, if this limitation is overwhelmed, a normal infection ensues. One can imagine at least two general ways that metabolic responses might interfere with the infection process. First, active SNF1 might ensure that cellular energy charge is sufficient to enable the rapid (and possibly localized) activation of metabolically expensive defense response pathways that act more directly to limit virus replication. Thus, the ability of a potential host to mount an effective defense against an invading pathogen might depend on the ability of its cells to maintain a positive energy balance. Second, SNF1-mediated responses might limit the availability of essential precursors by turning off certain biosynthetic pathways. Efficient virus replication requires a ready supply of nucleic acid and protein precursors that must be obtained from the cellular environment, and it is possible that one or more of these becomes limiting if biosynthesis is blocked after virus challenge. Certainly, these are very general mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive, and others are possible.

It bears repeating that enhanced resistance observed after the overexpression of SNF1, or enhanced susceptibility attributable to a reduction in SNF1 activity, can be attributed primarily to altered infectivity. Once infections are initiated in transgenic plants displaying either enhanced susceptibility or enhanced resistance, they proceed with normal kinetics and produce typical disease symptoms with normal levels of virus accumulation relative to nontransgenic plants (Sunter et al., 2001; this report). That is, there is no significant effect on virulence. This distinction between virulence and infectivity is especially relevant, because closely related AL2 homologs (called AC2) from African cassava mosaic virus and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (also members of the genus Begomovirus) have been identified as suppressors of RNA silencing (Voinnet et al., 1999; van Wezel et al., 2002). However, because experimental overexpression of AC2 and other viral silencing suppressors (e.g., HC-Pro from the potyvirus Tobacco etch virus) typically results in increased disease severity accompanied by a substantial increase in virus load (Brigneti et al., 1998; Kasschau and Carrington, 1998; Voinnet et al., 1999), it is difficult to directly associate the enhanced susceptibility phenotype we have characterized with the suppression of RNA silencing.

In support of this statement, we cite the well-established role of SNF1 as a metabolic regulator and note that silencing pathways are not impaired in line S-2, in which SNF1 transcripts either are not produced or do not accumulate. Thus AL2 and its AC2 and L2 homologs could play multiple roles in pathogenesis and might interact with different cellular partners to separately suppress both SNF1-mediated responses and RNA silencing. The different phenotypic consequences of AL2, L2, and AC2 expression in this case could be the result of the different methods of experimental observation: AL2 and L2 were expressed as single-copy or low-copy transgenes in N. benthamiana (Sunter et al., 2001), whereas AC2 was expressed from a high-copy Potato virus X–based vector in the same host (Voinnet et al., 1999; van Wezel et al., 2002). Lower level transgene expression may have allowed the less obvious enhanced susceptibility phenotype to be revealed. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that SNF1-mediated metabolic responses are necessary for the timely and efficient induction of RNA silencing, which could limit virus replication in initially infected cells. Thus, the viral proteins might suppress RNA silencing indirectly by inhibiting SNF1.

A third possibility is that AL2/L2 and AC2 have distinctly different functions in pathogenesis and target SNF1 responses and RNA silencing, respectively. Our recent finding that the AC2 protein of African cassava mosaic virus also interacts with SNF1 and ADK (our unpublished data) argues in favor of the first two possibilities but does not allow us to distinguish between them. At this point, the relationship between SNF1 responses and RNA silencing pathways must be regarded as an unresolved issue that awaits further characterization and a better understanding of how they are suppressed by geminivirus proteins.

In conclusion, our discovery that modulating SNF1 expression modulates susceptibility to virus infection supports the idea that alteration of metabolism is an important, innate response to virus challenge and suggests a direct molecular link between host metabolic status and pathogen susceptibility. Our observations that geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins interact with and inactivate SNF1 and ADK support this idea and demonstrate that geminiviruses are capable of manipulating host metabolism to their own advantage. Clearly, the position of SNF1 as a key regulator of important biosynthetic and catabolic pathways would make this kinase an attractive target if modification of metabolism were the goal. Given the conservation of SNF1/AMPK, the possibility that responses mediated by these kinases are a feature of antiviral defense in other eukaryotes warrants investigation.

METHODS

Yeast Two-Hybrid Analysis

Two-hybrid screens and experiments to assess the interaction of defined regions of AL2 and L2 with SNF1 were performed using the system described by Durfee et al. (1993). Bait constructs were expressed as GAL4 DNA binding domain (amino acids 1 to 147) fusion proteins from the yeast expression plasmid pAS2 or pGBT9 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Prey constructs were expressed as GAL4 activation domain fusion proteins from plasmid pACT2. Initial screens were performed with AL2 1-83 as bait (pGBY203; Hartitz et al., 1999) and an Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA library as prey (obtained from the ABRC, Ohio State University, Columbus). The yeast reporter strain Y190 contains the lacZ and HIS3 genes under the control of the GAL1 promoter, which contains GAL4 binding sites (Harper et al., 1993). Plasmids pAS2 and pACT2, derivatives containing yeast SNF1, and yeast strain Y190 were kindly provided by Stephen Elledge (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). Positive interaction was indicated by the ability of Y190 cells cotransformed with bait and prey constructs to grow on synthetic medium lacking His and containing 50 mM 3-aminotriazole. The medium also lacked Leu and Trp to ensure the maintenance of expression plasmids. Additional confirmation and approximate quantitation of interactions was obtained by assessing β-galactosidase activity using a filter-lift assay.

A PCR product containing the complete SNF1 (AKIN11) coding region was generated from the original cDNA from the screen, using 5′-GCGCTCGAGCCATGGATCATTCATC-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-GCGGGATCCTCAGATCACACGAAGC-3′ as the reverse primer. The product was cleaved with NcoI and BamHI and inserted into similarly cleaved pAS2 and pACT2. The resulting constructs were designated pAS-aSNF1 and pACT-aSNF1. Full-length Tomato golden mosaic virus (TGMV) AL2 and Beet curly top virus (BCTV) (strain Logan) L2, and defined regions thereof, were tested for interaction with Arabidopsis SNF1. Constructs containing full-length AL2 or L2 were generated by PCR using pTGA26 as a template for the former (Sunter et al., 1990) and pCT8 as a template for the latter (Hormuzdi and Bisaro, 1995), as described elsewhere (Hartitz et al., 1999). Constructs containing defined regions of AL2 were generated by PCR using primers appropriate for the construction of AL2 open reading frames (ORFs) beginning at amino acid 1, 10, 20, 30, or 36 with a reverse primer corresponding to the 3′ end of the ORF (amino acid 129), except in the case AL2 1-32, in which the reverse primer corresponded to amino acid 32.

Deletion of the 3′ end of AL2 from constructs other than AL2 1-32 was affected by restriction enzyme digestion: truncation at amino acid 83 was produced by BamHI cleavage, and truncation at amino acid 43 was produced by PstI cleavage. Internal deletion AL2 Δ33-43 was constructed by ligating the coding region from AL2 1-32 with the PstI-BamHI fragment corresponding to amino acids 43 to 83 for insertion into pAS2 or with the PstI fragment corresponding to amino acids 43 to 129 for insertion into pACT2. A pAS-based intermediate construct containing AL2 Δ33-43 in a full-length background (amino acids 1 to 129) also was constructed. This plasmid, pTGA571, later was used for transgene construction. A construct expressing amino acids 1 to 100 of L2 was generated from the full-length construct (amino acids 1 to 174) by cleavage at an internal EcoRI site. L2 1-72 was created by PCR synthesis of the complete L2 coding region from a pCT44 template, which contains a frameshift mutation at amino acid 72 (Hormuzdi and Bisaro, 1995). L2 66-79 was created by annealing complementary oligonucleotides corresponding to this region of the L2 gene. All SNF1-, AL2-, and L2-based constructs were sequenced before use in the two-hybrid system.

Construction of Transgenic Plants

Binary Ti plasmids containing the Arabidopsis SNF1 coding region were constructed. The SNF1 coding region from pAS-aSNF1 was inserted into pET3 (Stratagene) and subsequently recovered from this plasmid by PCR using 5′-GGAGATCTACATATGCATCAC-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-GCGGGATCCTCAGATCACACGAAGC-3′ as the reverse primer. The PCR product was cleaved with BglII and BamHI and inserted into a BglII site between the 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus and the nopaline synthase polyadenylation signal in the Ti plasmid vector pMON530 (Rogers et al., 1987). The resulting constructs were examined for insert orientation. Sense and antisense constructs were identified and designated pSNF-S and pSNF-AS, respectively.

A binary Ti plasmid containing SNF1 interaction–defective AL2 (AL21-32;44-129) was constructed beginning with pTGA571, which contains AL2 Δ33-43 in a full-length background (amino acids 1 to 129). A PCR fragment with the internal deletion in a 1-114 background was generated using 5′-GCGAGATCTATGCGAAATTCGTCTTCC-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-GCGGAGCTCCTAAAGTTGAGAAATGCC-3′ as the reverse primer. The PCR product was cleaved with BglII and inserted into BglII- and SmaI-cleaved pMON530 between the 35S promoter and the nopaline synthase polyadenylation signal. The resulting construct was designated pTGA4259.

Ti plasmids pSNF-S, pSNF-AS, and pTGA4259 were transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3111SE containing the disarmed Ti plasmid pTiB36SE by triparental mating, and cultures were used to transform Nicotiana benthamiana leaf discs (Horsch and Klee, 1986). Transformed shoots were selected on the basis of kanamycin resistance (300 μg/mL), and the presence of the transgene in subsequently regenerated plants was confirmed by PCR amplification of integrated sequences (Sunter and Bisaro, 1997). Seeds derived from selfed transgenic plants were surface-sterilized and germinated on MSO medium (Murashige and Skoog [1962] salts, B5 vitamins, and 30 g/L sucrose) containing kanamycin (300 μg/mL). Seedlings were transferred to soil and used as a source of RNA or for infectivity analysis.

Analysis of Transgene Expression

RNA samples were prepared from nontransgenic N. benthamiana and Arabidopsis plants and N. benthamiana plants containing sense and antisense SNF1 transgenes. Starting material for each sample consisted of pooled leaves from five individual plants. Total RNA was obtained using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from total RNA preparations using the Oligomex kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR was performed with total RNA preparations that were treated previously with RQ1 DNase (Promega) and extracted with phenol. Reverse transcription was accomplished using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL) with randomly sheared, denatured salmon sperm DNA as primer. PCR was performed subsequently on aliquots of each cDNA preparation using primer sets specific for SNF1 (AKIN11: forward, 5′-GATGTATGGAGTTGCG-3′; reverse, 5′-CGCATAGGATTGGAACC-3′) or 18S ribosomal RNA (Ambion, Austin, TX).

RNA and reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR samples were subjected to RNA and DNA gel blot hybridization, respectively. A total (mixed) SNF1-specific probe was prepared from band-isolated SNF1 sequence using the DECAprimer II DNA labeling kit (Ambion). To prepare sense- and antisense-specific SNF1 riboprobes, the SNF1 coding region was inserted into pGEM3 (Promega) and transcribed subsequently with SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of α-32P-GTP. Gel blot signals were quantitated by phosphorimaging (Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX) and normalized using internal ATPase control signals.

To determine AL2 transgene expression levels, RNA samples were prepared from N. benthamiana plants containing AL21-100 and AL21-32;44-114 transgenes. In this case, source material consisted of ∼100 seedlings from each line germinated on MSO medium containing kanamycin (300 μg/mL). Total RNA was obtained using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples were subjected to RNA gel blot hybridization using an AL2-specific probe prepared from band-isolated AL2 sequence with the DECAprimer II DNA labeling kit (Ambion). Gel blot signals were quantitated by phosphorimaging (Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX) and normalized using internal 18S RNA controls.

Infectivity Experiments

Agroinoculation of plants with TGMV and BCTV was performed as described (Sunter et al., 2001). Transgenic seeds were germinated in MSO medium containing kanamycin (300 μg/mL) to ensure the presence of the transgene before transfer to soil. Nontransgenic seeds were germinated in the same medium lacking kanamycin. Plants were inoculated at 30 to 40 days after germination and scored for the appearance of disease symptoms typical of TGMV or BCTV infection. Latent periods (days [mean ± se] after inoculation until the onset of visible symptoms) were recorded, and statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance and Dunnett's test. Quantal assays to determine the inoculum concentration necessary to elicit infection of half of the plants were performed by agroinoculating BCTV to groups of transgenic and nontransgenic plants with serial fivefold dilutions of a standard dose (OD600 = 1 = ∼109 Agrobacterium cells/mL). A total inoculum volume of 30 μL was used per plant.

Protein Expression and Kinase Assay

GST-AL2 and His-tagged L2 were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli BL21 cells as described previously (Hartitz et al., 1999). The baculovirus expression system (Gibco BRL) was used to express His-tagged SNF1, SNF1-KD, and SNF1 K49R proteins. The full-length SNF1 sequence was obtained from pAS-aSNF1 as an NcoI-BamHI fragment (the BamHI end was rendered flush ended before NcoI digestion). The fragment then was inserted into NcoI-EcoICRI–cleaved pHTb. The kinase domain sequence (SNF1-KD, amino acids 1 to 343) was generated from full-length sequence by removal of an XbaI-SmaI fragment, and the K49R mutation was introduced into the kinase domain fragment by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using the overlapping primer set 5′-GCTATCAGAATTCTTAATCG-3′/5′-CGATTAAGAATTCTGATAGC-3′ (altered codons are underlined). The SNF1, SNF1-KD, and SNF1-KD K49R constructs were used to generate recombinant baculoviruses that were inoculated subsequently to insect (Sf9) cells. The His-tagged proteins expressed from the baculoviruses were purified using nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid agarose resin (Qiagen). Protein concentrations were estimated by comparing band intensities with BSA standards on Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250–stained polyacrylamide gels.

Kinase assays were performed essentially as described by Celenza and Carlson (1989). Reactions were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, and 10 mM MgCl2 in a total volume of 40 μL. In independent experiments, reactions contained 25 to 50 ng of SNF1-KD (or SNF1-KD K49R) with and without varying molar ratios of inhibitor proteins (AL2 or L2) or negative control proteins (GST or CAT). Reactions were initiated by the addition of γ-32P-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol; DuPont–New England Nuclear) to a final concentration of 0.05 μM and incubated for 20 min at room temperature before electrophoresis on SDS–polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane that was subjected sequentially to autoradiography and immunoblot analysis using an anti-His antibody. Labeled proteins were visualized and quantitated using a phosphorimager.

Yeast Complementation Experiments

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae snf1 deletion strain BY4742 was obtained from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL; record number 14311). The SNF1 and SNF1-KD sequences were obtained by PCR, and products were cleaved with BamHI and inserted between the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter and the 3-phosphoglycerate kinase polyadenylation signal in low-copy (YCpL) and high-copy (YEpL) plasmids that permit Leu selection. PCR used pHTb-SNF1 as a template with 5′-GCGGGATCCATGGATCATTCATC-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-GCGGGATCCTCAGATCACACGAAGC-3′ as the reverse primer for full-length SNF1 and 5′-CCTGAAACTCGGATGGATCCT-AGCC-3′ as the reverse primer for SNF1-KD. The L2 sequence from pRSET-L2 (our unpublished work) was inserted as a BamHI fragment into the similar YEpU plasmid that provides uracil selection.

Upon request, all novel materials described in this article will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenn Buckley, Erich Grotewold, and Deborah Parris for valuable discussions and advice during the course of this study and Janet Sunter for assistance with plant infectivity experiments. We also thank Stephen Elledge for providing yeast two-hybrid strains and expression plasmids and Paul Herman for providing the yeast expression plasmids YCpL, YEpL, and YEpU. The Arabidopsis cDNA library was obtained from the ABRC at Ohio State University (National Science Foundation/Department of Energy/U.S. Department of Agriculture Collaborative Research in Plant Biology Program [USDA 92-37105-7675]). This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (NRI-00-35301-9084).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.009530.

References

- Bhalerao, R.P., Salchert, K., Bakò, L., Ökrész, L., Szabados, L., Muranaka, T., Machida, Y., Schell, J., and Konz, C. (1999). Regulatory interaction of PRL1 WD protein with Arabidopsis SNF1-like protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5322–5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaro, D.M. (1996). Geminivirus replication. In DNA Replication in Eukaryotic Cells, M. DePamphilis, ed (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press), pp. 833–854.

- Brigneti, G., Voinnet, O., Li, W.-X., Ji, L.-H., Ding, S.-W., and Baulcombe, D.C. (1998). Viral pathogenicity determinants are suppressors of transgene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. EMBO J. 17, 6739–6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Carlson, M. (1999). Glucose repression in yeast. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2, 202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celenza, J.L., and Carlson, M. (1986). A yeast gene that is essential for release from glucose repression encodes a protein kinase. Science 233, 1175–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celenza, J.L., and Carlson, M. (1989). Mutational analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF1 protein kinase and evidence for functional interaction with the SNF4 protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 5034–5044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikano, H., Ogawa, M., Ikeda, Y., Koizumi, N., Kusano, T., and Sano, H. (2001). Two novel genes encoding SNF1-related protein kinases from Arabidopsis thaliana: Differential accumulation of AtSR1 and AtSR2 transcripts in response to cytokinins and sugars, and phosphorylation of sucrose synthase by AtSR2. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264, 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S.P., Helps, N.R., Cohen, P.T.W., and Hardie, D.G. (1995). 5′-AMP inhibits dephosphorylation, as well as promoting phosphorylation, of the AMP-activated protein kinase: Studies using bacterially expressed human protein phosphatase-2Cα and native bovine protein phosphatase-2Ac. FEBS Lett. 377, 421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durfee, T., Becherer, K., Chen, P.-L., Yeh, S.-H., Yang, Y., Kilburn, A.E., Lee, W.-H., and Elledge, S.J. (1993). The retinoblastoma protein associates with the protein phosphatase type 1 catalytic subunit. Genes Dev. 7, 555–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrás, R., Ferrando, A., Jásik, J., Kleinow, T., Ökrész, L., Tiburcio, A., Salchert, K., del Pozo, C., Schell, J., and Koncz, C. (2001). SKP1-SnRK protein interactions mediate proteosomal binding of a plant SCF ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 20, 2742–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields, S., and Song, O. (1989). A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 340, 245–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, C. (1999). Geminivirus DNA replication. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56, 313–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford, N., and Hardie, D.G. (1998). SNF1-related protein kinases: Global regulators of carbon metabolism in plants? Plant Mol. Biol. 37, 735–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley-Bowdoin, L., Settlage, S., Orozco, B.M., Nagar, S., and Robertson, D. (1999). Geminiviruses: Models for plant DNA replication, transcription, and cell cycle regulation. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 18, 71–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie, D.G., Carling, D., and Carlson, M. (1998). The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: Metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 821–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper, J.W., Adami, G.R., Wei, N., Keyomarsi, K., and Elledge, S.J. (1993). The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinase. Cell 75, 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartitz, M.D., Sunter, G., and Bisaro, D.M. (1999). The geminivirus transactivator (TrAP) is a single-stranded DNA and zinc-binding phosphoprotein with an acidic activation domain. Virology 263, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, S.A., Selbert, M.A., Goldstein, E.G., Edelman, A.M., Carling, D., and Hardie, D.G. (1995). 5′-AMP activates the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade, and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I cascade, via three independent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 27186–27191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbers, K., Meuwly, P., Frommer, W.B., Metraux, J.-P., and Sonnewald, U. (1996). Systemic acquired resistance mediated by ectopic expression of invertase: Possible hexose sensing in the secretory pathway. Plant Cell 8, 793–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormuzdi, S.G., and Bisaro, D.M. (1995). Genetic analysis of beet curly top virus: Examination of the roles of L2 and L3 genes in viral pathogenesis. Virology 206, 1044–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch, R.B., and Klee, H.J. (1986). Rapid assay of foreign gene expression in leaf discs transformed by Agrobacterium tumefaciens: Role of the T-DNA borders in the transfer process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83, 4428–4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.-C., and Sheen, J. (1997). Sugar sensing in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R., and Ryan, C.A. (1990). Wound-inducible potato inhibitor II genes: Enhancement of expression by sucrose. Plant Mol. Biol. 14, 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M. (1999). Feasting, fasting, and fermenting: Glucose sensing in yeast and other cells. Trends Genet. 15, 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasschau, K.D., and Carrington, J.C. (1998). A counterdefensive strategy of plant viruses: Suppression of posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell 95, 461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchin, S., Treich, I., and Carlson, M. (2000). A regulatory shortcut between the Snf1 protein kinase and RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7916–7920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guen, L., Thomas, M., Bianchi, M., Halford, N.G., and Kreis, M. (1992). Structure and expression of a gene from Arabidopsis thaliana encoding a protein related to SNF1 protein kinase. Gene 120, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranaka, T., Banno, H., and Machida, Y. (1994). Characterization of tobacco protein kinase NPK5, a homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF1 that constitutively activates expression of the glucose-repressible SUC2 gene for a secreted invertase of S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 2958–2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473.–497. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, K., et al. (1998). Pleiotropic control of glucose and hormone responses by PRL1, a nuclear WD protein, in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 12, 3059–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.G., Klee, H.J., Horsch, R.B., and Fraley, R.T. (1987). Improved vectors for plant transformation: Expression cassette vectors and new selectable markers. Methods Enzymol. 153, 253–277. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, J., Latham, J., Pinner, M.S., Bedford, I., and Markham, P.G. (1992). Mutational analysis of the monopartite geminivirus beet curly top virus. Virology 191, 396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, A., and Chrispeels, M.J. (1990). cDNA cloning of carrot extracellular β-fructosidase and its expression in response to wounding and bacterial infection. Plant Cell 2, 1107–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden, C., Crawford, R.M., Halford, N.G., and Hardie, D.G. (1999. a). Regulation of spinach SNF1-related (SnRK1) kinases by protein kinases and phosphatases is associated with phosphorylation of the T loop and is regulated by 5′-AMP. Plant J. 19, 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden, C., Donaghy, P.G., Halford, N., and Hardie, D.G. (1999. b). Two SNF1-related protein kinases from spinach leaf phosphorylate and inactivate 3-hydroxyl-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, nitrate reductase, and sucrose phosphate synthase in vitro. Plant Physiol. 120, 257–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunter, G., and Bisaro, D.M. (1992). Transactivation of geminivirus AR1 and BR1 gene expression by the viral AL2 gene product occurs at the level of transcription. Plant Cell 4, 1321–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunter, G., and Bisaro, D.M. (1997). Regulation of a geminivirus coat protein promoter by AL2 protein (TrAP): Evidence for activation and derepression mechanisms. Virology 232, 269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunter, G., Hartitz, M.D., Hormuzdi, S.G., Brough, C.L., and Bisaro, D.M. (1990). Genetic analysis of tomato golden mosaic virus: ORF AL2 is required for coat protein accumulation while ORF AL3 is necessary for efficient DNA replication. Virology 179, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunter, G., Sunter, J., and Bisaro, D.M. (2001). Plants expressing tomato golden mosaic virus AL2 or beet curly top virus L2 transgenes show enhanced susceptibility to infection by DNA and RNA viruses. Virology 285, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya, H., Oshima, T., Naito, S., Chino, M., and Komeda, Y. (1991). Sugar-dependent expression of the CHS-A gene for chalcone synthase from petunia in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 97, 1414–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel, R., Liu, H., Tien, P., Stanley, J., and Hong, Y. (2001). Gene C2 of the monopartite geminivirus tomato yellow leaf curl virus-China encodes a pathogenicity determinant that is localized in the nucleus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14, 1125–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel, R., Liu, H., Tien, P., Stanley, J., and Hong, Y. (2002). Mutation of three cysteine residues in tomato yellow leaf curl virus-China C2 protein causes dysfunction in pathogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing-suppression. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15, 203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet, O., Pinto, Y.M., and Baulcombe, D.C. (1999). Suppression of gene silencing: A general strategy used by diverse DNA and RNA viruses of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14147–14152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekes, J., Ball, K.L., Caudwell, F.B., and Hardie, D.G. (1993). Specificity determinants for the AMP-activated protein kinase and its plant homologue analysed using synthetic peptides. FEBS Lett. 334, 335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]