Abstract

Three microscopic in situ techniques were used simultaneously to investigate viability and activity on a single-cell level in activated sludge. The redox dye 5-cyano-2,3-tolyl-tetrazolium chloride (CTC) was compared with microautoradiography (MAR) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to indicate activity of cells in Thiothrix filaments and in single floc-forming bacteria. The signals from MAR and FISH correlated well, whereas only 65% of the active Thiothrix cells and 41% of all single cells were detectable by CTC reduction, which mainly targeted the most active cells.

Reliable methods to detect the viable fraction of microorganisms in complex environments are of general interest in microbial ecology. Among the methods with single-cell resolution are fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (1), microautoradiography (MAR) (3), and reduction of the redox dye 5-cyano-2,3-tolyl-tetrazolium chloride (CTC) (13). In theory, FISH reflects the recent activity state of the cell, but this depends very much on species and growth conditions (7, 9, 12), so it can hardly be used in undefined, mixed communities. By using MAR, the incorporation of radioactively labeled substrate into the active bacteria in a population can be detected. The main problem here is, however, to find substrate(s) that can be taken up by all active bacteria. An easy and often used method is the reduction of CTC by the respiratory electron transport chain to insoluble, fluorescent formazan crystals (CTF). This method is commonly applied to determine respiratory activity and viability of bacteria in many different complex microbial systems (4, 6, 13). However, several studies indicate that this method is unable to detect all active cells and thus underestimate the real number if it is compared to the other two methods (e.g., references 6 and 14). The reason for this inconsistency is still unknown (5), but it has been suggested that the CTC was poisonous to the cells and that CTC targets only the most active cells (14). In this study we have visualized the signal from MAR and FISH with the reduction of CTC on the same cell in order to determine the nature of cells targeted by CTC. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate whether reduction of CTC is a reliable method for detecting the activity of cells in complex microbial systems and to improve the knowledge of the role of the physiological state of the cells targeted by the CTC redox dye.

For the investigation, activated sludge samples with a high number of the filamentous Thiothrix sp. bacteria were used (11). Incubations with 2 ml of activated sludge (1 mg of suspended matter per ml), 2 mM acetate, 10 μCi of [3H]acetate (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom), and 5 mM CTC (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, Pa.) were carried out at room temperature for 50 min in the dark. A longer incubation time did not result in any change in the total number of CTC-positive cells (data not shown). Fixation, immobilization, dehydration, and further application of the oligonucleotide probes were performed according to the procedure described by Amann et al. (1) by using the universal bacterial probe EUB338 to monitor most Bacteria, while the Tni probe specific to Thiothrix nivea (1) was used to detect Thiothrix sp. The MAR procedure and the proper controls were performed according to the procedure described by Andreasen and Nielsen (2). Semiquantitative variations in silver grain density were determined following the procedure described by Nielsen et al. (11). Visualization of the combined fluorescent signals and the MAR signals was performed using a laser-scanning microscope (LSM) (8). The number of CTC-positive cells measured by normal epifluorescence microscopy yielded estimates that were slightly lower than the number measured by image processing with the LSM. FISH in combination with CTC was carried out using 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (FLUOS)-labeled oligonucleotide probes (Interactiva, Ulm, Germany). The fluorescence signal from the FLUOS-labeled FISH probes was most easily distinguished from the fluorescence signal deriving from the CTF by usage of a band-pass filter with a window between 505 and 530 nm and excitation by an argon laser (488 nm). The formazan signal was examined by using a band-pass filter with a window between 560 and 615 nm and excitation at 543 nm by a HeNe laser.

Most Thiothrix filaments exhibited a strong fluorescence signal with both rRNA probes tested, indicating a high content of ribosomes. Almost all cells within the filaments were FISH positive, and only a few cells within the filaments (<5%) were very faint or did not hybridize with the probe. All FISH-detectable Thiothrix cells (>99%) took up the tritium-labeled acetate as indicated by formation of silver grains on top of the filaments with a single-cell resolution (MAR positive). An even distribution of silver grains along the individual filaments indicated a similar activity level and thus similar physiological state in all cells in each filament. However, up to a threefold variation in grain density was observed between the different filaments, indicating variations in the activity levels. In a few Thiothrix filaments, there were empty spaces indicating inactive or absent cells; these filaments were typically found among the filaments with the lowest uptake of radiolabeled acetate. Longer incubation times did not change the ratio between MAR-positive and MAR-negative cells.

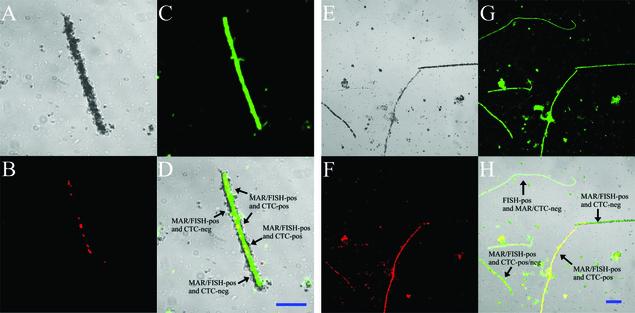

Only 65% of the FISH- and MAR-positive Thiothrix cells were also CTC positive (Fig. 1). However, when the filaments generally were CTC positive, nearly all cells within the filaments were CTC positive. Thus, most of the FISH- and MAR-positive Thiothrix filaments (75 to 78%) had a high fraction of CTC-positive single cells (>80%). In a minor part of the FISH- and MAR-positive filaments (6 to 12%), only very few CTC-positive cells were present within the filaments (<10%), indicating inability of the CTC method to show these active cells. Furthermore, the group of Thiothrix filaments with gaps of FISH- and MAR-negative cells along the filament always had very low yields of CTC-positive cells along the filament. As these filaments had the lowest density of silver grains on top of the cells, there seemed to be a correlation between a low activity and lack of a CTC signal. The intensity of the fluorescent FISH signal showed a difference of only 10 to 20% between the cells with the lowest intensity and the cells with the highest intensity. This variation correlated with the variation in the uptake of labeled acetate measured as silver grain density on top of the filaments (r2 = 0.82).

FIG. 1.

MAR-CTC-FISH combination on filamentous bacteria in activated sludge. Light microscopy showing MAR-positive cells ([3H]acetate) (A and E); CTC-positive cells (B and F); hybridization with the Thiothrix-specific probe Tni (C) and with the bacterial probe EUB338 (G), both FLUOS labeled; and the superimposed images from panels A to C and panels E to G (D and H, respectively). Panels A to D show a single Thiothrix filament containing approximately 15 cells, of which only seven cells are CTC positive. Panels E to G show the presence of various combinations of CTC-negative and -positive filamentous bacteria. Bar = 5 μm.

Optical sectioning with confocal LSM of the CTC-positive cells revealed that the number of crystals in each cell varied between one and five crystals, and variations in the size of the crystals were also observed. Most cells had only one crystal, but approximately 10% of the CTC-positive filaments had cells with two to five crystals. The number had a tendency to follow the cell volume and the silver grain density of the MAR signal. Cell sizes were determined to be between 0.8 by 1.1 μm and 1.0 by 1.3 μm. This indicates that the most active cells yielded more CTF and thus brighter CTC signals.

The presence of CTF in MAR-positive nonfilamentous floc-forming bacteria found between the filaments was similarly examined. Of the single cells that were targeted by the universal bacterial probe EUB338 and had a positive MAR signal, 41% were also CTC positive. Furthermore, as with the filaments, single cells without a positive FISH or MAR signal were never found to be CTC positive.

The results clearly showed that the CTC reduction assay did not hit all active cells within the Thiothrix filaments or all active single cells in the activated sludge investigated. Sherr et al. (14) speculated that CTC reduction detects only the most active bacteria and not the viable but inactive cells. In our work we have shown that many entire Thiothrix filaments and many single cells that were clearly MAR and FISH positive were not detected by CTC reduction. From the number of silver grains deposited on top of the active cells and the incubation conditions used, it was possible to estimate the average cell-specific uptake rate of acetate to at least 10−15 mol · cell−1 · h−1 (10). This in situ cell-specific uptake rate is comparable to that for actively growing cells in pure culture (15). The silver grain density among the weakest MAR-positive cells in the Thiothrix filaments was typically similar to or higher than that for the nonfilamentous bacteria. This indicates that the Thiothrix cells were indeed very active in the sludge despite several of them being CTC negative. The correlation between the CTC signal and the silver grain density on top of the Thiothrix cells found in this study indicates that there was some relationship between activity and the ability to reduce CTC.

The fraction of CTC-positive bacteria of all MAR-positive bacteria was within the range of the number of active cells recorded by Flood et al. (4) in a wetland system (ranging from 4 to 44% of the MAR count) and much higher than the number described in a marine system (approximately 1% of the MAR count [6]). These differences between the different environments have so far been attributed to the generally higher activity in the activated sludge, but the reasons for the poor and various CTC results are still not known. However, by using the simultaneous staining of FISH, MAR, and CTC on the very same cells, our results clearly show that CTC reduction greatly underestimates the number of active cells and that this seems only partially related to the activity level. This is in accordance with the previous finding that certain cells lack the ability to reduce CTC to CTF but is inconsistent with the suggested explanation that the discrepancy between MAR- and CTC-positive cells is caused by a toxic effect of CTC on the bacterial metabolism (5).

The best way to enumerate active bacteria in a complex microbial system seems to be by MAR, maybe combined with FISH for identification. Using several different labeled substrates and incubating under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions will in our opinion ensure the best detection of most active bacteria. In conclusion, the CTC assay can only be used to give the minimum number of (very) active cells in a certain system, as all CTC-positive cells were indeed viable because they also were FISH and MAR positive. Therefore, in complex systems CTC should be used with great care.

Acknowledgments

The Danish Technical Research Council supported this study under the framework program “Activity and Diversity in Complex Microbial Systems.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R., W. Ludwig, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen, K., and P. H. Nielsen. 1997. Application of microautoradiography to study substrate uptake by filamentous microorganisms in activated sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3662-3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brock, T. D., and M. L. Brock. 1966. Autoradiography as a tool in microbial ecology. Nature 209:734-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flood, J. A., N. J. Ashbolt, and P. C. Pollard. 1999. Complementary inde pendent molecular, radioisotopic and fluorogenic techniques to assess biofilm communities in two wastewater wetlands. Water Sci. Technol. 39:65-70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joux, F., and P. Lebaron. 2000. Use of fluorescent probes to assess physiological functions of bacteria at single-cell level. Microbes Infect. 2:1523-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karner, M., and J. A. Fuhrman. 1997. Determination of active marine bacterioplankton: a comparison of universal 16S rRNA probes, autoradiography, and nucleoid staining. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1208-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemp, P. F., S. Lee, and J. LaRoche. 1993. Estimating the growth rate of slowly growing marine bacteria from RNA content. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2594-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee, N., P. H. Nielsen, K. H. Andreasen, S. Juretschko, J. L. Nielsen, K.-H. Schleifer, and M. Wagner. 1999. Combination of fluorescent in situ hybridization and microautoradiography—a new tool for structure-function analyses in microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1289-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molin, S., and M. Givskov. 1999. Application of molecular tools for in situ monitoring of bacterial growth activity. Environ. Microbiol. 1:383-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen, J. L., and P. H. Nielsen. 2002. Enumeration of acetate-consuming bacteria by microautoradiography under oxygen and nitrate respiring conditions in activated sludge. Water Res. 36:421-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen, P. H., M. Aquino de Muro, and J. L. Nielsen. 2000. Studies on the in situ physiology of Thiothrix spp. in activated sludge. Environ. Microbiol. 2:389-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulsen, L. K., G. Ballard, and D. A. Stahl. 1993. Use of rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization for measuring the activity of single cells in young and established biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1354-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez, G. G., D. Phipps, K. Ishiguro, and H. F. Ridgeway. 1992. Use of fluorescent redox probe for direct visualization of actively respiring bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1801-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherr, B. F., P. del Giorgio, and E. B. Sherr. 1999. Estimating abundance and single-cell characteristics of respiring bacteria via the redox dye, CTC. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 18:117-131. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tempest, D. W., and O. M. Neijssel. 1992. Physiological and energetic aspects of bacterial metabolite overproduction. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 79:169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]