Abstract

Hydroxycinnamates are ubiquitous in the environment because of their contributions to the structure and defense mechanisms of plants. Additional plant products, many of which are formed in response to stress, support the growth of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 through pathways encoded by genes in the dca-pca-qui-pob chromosomal cluster. In an appropriate genetic background, it was possible to select for an Acinetobacter strain that had lost the ability to grow with caffeate, a commonly occurring hydroxycinnamate. The newly identified mutation was shown to be a deletion in a gene designated hcaC and encoding a ligase required for conversion of commonly occurring hydroxycinnamates (caffeate, ferulate, coumarate, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate) to thioesters. Linkage analysis showed that hcaC is linked to pobA. Downstream from hcaC and transcribed in the direction opposite the direction of pobA transcription are open reading frames designated hcaDEFG. Functions of these genes were inferred from sequence comparisons and from the properties of knockout mutants. HcaD corresponded to an acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) dehydrogenase required for conversion of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionyl-CoA to caffeoyl-CoA. HcaE appears to encode a member of a family of outer membrane proteins known as porins. Knockout mutations in hcaF confer no discernible phenotype. Knockout mutations in hcaG indicate that this gene encodes a membrane-associated esterase that hydrolyzes chlorogenate to quinate, which is metabolized in the periplasm, and caffeate, which is metabolized by intracellular enzymes. The chromosomal location of hcaG, between hcaC (required for growth with caffeate) and quiA (required for growth with quinate), provided the essential clue that led to the genetic test of HcaG as the esterase that produces caffeate and quinate from chlorogenate. Thus, in this study, organization within what is now established as the dca-pca-qui-pob-hca chromosomal cluster provided essential information about the function of genes in the environment.

Hydroxycinnamates are abundant in plants and are used in both structural (3, 4, 61) and chemical (6) plant defense strategies. These compounds occur freely or as components of plant polymers, such as suberin (3, 4, 23, 38, 61). Highly significant among the hydroxycinnamates is chlorogenate, which is the most abundant phenolic compound in potato tubers (37) and accounts for 1.5% of the dry weight of defatted sunflower oil (22). Chlorogenate has numerous functions, including effects on disease resistance (39) and on the palatability of leaves to insects (27). The production of animal feeds is hindered by the presence of chlorogenic acid, which binds to proteins and keeps them from being fully metabolized (22).

Chlorogenate is an ester, and hydrolysis of its most common form (5-O-caffeoylquinic acid) produces quinate and caffeate, a free hydroxycinnamate (Fig. 1). Included in the chemical family of chlorogenates are additional esters of caffeate, and these compounds are hydrolyzed with various degrees of efficiency by an extracellular chlorogenate esterase (EC 3.1.1.43) from Aspergillus niger (54, 55) or Aspergillus japonicus (45, 46). A preparation of the latter enzyme is commercially available http://www.kikkoman.co.jp/bio/j/rinsyou/enzymes/ and is used to control bitterness and to prevent enzymatic browning in the preparation of juice, wine, and coffee. Chlorogenate esterase has been identified as an intracellular enzyme in gut bacteria (7), but little is known about genes encoding this enzyme or how their expression is controlled.

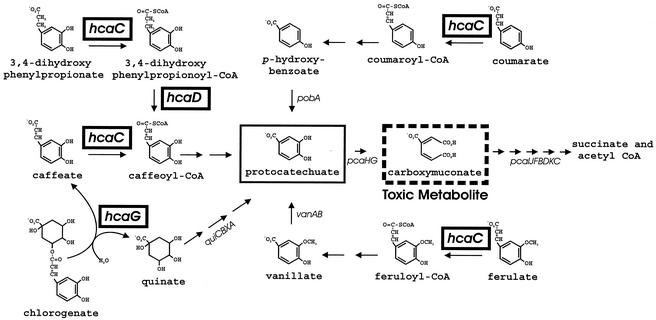

FIG. 1.

Metabolic pathways converging upon protocatechuate in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. The ΔpcaBDK1 deletion blocks metabolism of carboxymuconate (dashed box). Accumulation of this compound prevents growth in the presence of protocatechuate (box) or its metabolic precursors, and this allows selection of strains with secondary mutations that prevent metabolism of these compounds (20). Replacement of ΔpcaBDK1 with wild-type DNA produces strains in which the secondary mutation is the only genetic barrier to catabolism. In previous investigations researchers reported properties of mutants blocked in expression of pcaHG (10, 20), pobA (14, 26), and vanAB (43, 56). In this report we describe a spontaneous hcaC (box) mutant unable to metabolize caffeate. As shown here, the ΔhcaC1 mutation appears to inactivate a CoA ligase required for growth with coumarate, ferulate, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate, as well as caffeate. Between hcaC and pobA in the Acinetobacter chromosome are the structural genes hcaD (box), encoding an enzyme that oxidizes 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionyl-CoA to caffeoyl-CoA, and hcaG (box), encoding an enzyme that hydrolyzes chlorogenate to quinate and caffeate. Wild-type Acinetobacter cells exhibit doubling times ranging from 40 min to 1 h when they are grown at the expense of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate, coumarate, ferulate, quinate, caffeate, or chlorogenate.

Here we describe bacterial hca genes for catabolism of the ester chlorogenate and the free hydoxycinnamates caffeate, ferulate, coumarate, and 3,4-dihydroxypropionyl coenzyme A (3,4-dihydroxypropionyl-CoA) (Fig. 1). The genetic analysis was conducted with Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (also known as strain BD413 [31]) because of this organism's extraordinary competence for natural transformation (30). An additional convenience for study of catabolic genes was afforded by the toxicity of carboxymuconate, the product of protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase. As summarized in Fig. 1, strains unable to metabolize carboxymuconate can be used to select mutants defective in protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase and in metabolic pathways that converge upon protocatechuate (26). The initial evidence (2) for clustering of Acinetobacter genes for metabolic pathways converging through protocatechuate emerged from characterization of mutant strains blocked in expression of pcaHG, which are structural genes for protocatechuate oxygenase, and pobA, which is the structural gene for p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (Fig. 1). Chromosomal fragments containing pobA and surrounding DNA were cloned (2, 13). Analysis of open reading frames between pcaHG and pobA revealed that the quiBCXA cluster is required for conversion of quinate to protocatechuate (17, 18).

Spontaneous mutants lacking pcaHG often have large deletions (20), and some of these deletions prevent growth with straight-chain dicarboxylic acids (8). This finding led to elucidation of dca genes required for growth with the acids having chain lengths ranging from 6 to 16 carbon atoms (48). The dicarboxylic acids and hydroxycinnamates are major components of suberin (3, 4, 23, 38, 61). Thus, the overall dca-pca-qui-pob cluster was known to contain independently transcribed groups of genes that allow growth with plant products, including dicarboxylic acids (dca), protocatechuate (pca), quinate (qui), and p-hydroxybenzoate (pob). An exception to this pattern of clustering was provided by the unlinked vanAB genes encoding the demethylase that converts vanillate to protocatechuate (56).

Vanillate is an intermediate in catabolism of ferulate (11, 19, 44, 51, 58). The location of Acinetobacter genes for metabolism of ferulate and other hydroxycinnamates was unknown. As described here, a strain containing a spontaneous mutation blocking catabolism of a hydroxycinnamate, caffeate (Fig. 1), was isolated, and a cloned restriction fragment containing pobA was shown to restore wild-type function to the mutant strain. Designed mutations altering DNA within the fragment allowed identification of open reading frames required for metabolism of hydroxycinnamates, including chlorogenate (5-O-caffeoylquinate). The newly discovered genes expand our knowledge of the dca-pca-qui-pob-hca supraoperonic cluster, which makes a major contribution to the metabolic versatility of Acinetobacter. The phenotypic characterization of clustered genes provides clues about biological sources of the mixtures of nutrients used by bacteria in the natural environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

Plasmids and relevant mutants of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 are listed in Table 1. Acinetobacter strains were routinely grown at 37°C in mineral medium supplemented with 10 mM succinate, 5 mM p-hydroxybenzoate, or one of the following compounds at a concentration of 3 mM: caffeate, quinate, coumarate, 3,4 dihydroxyphenylpropionate, protocatechuate, chlorogenate (5-O-caffeoylquinate), or ferulate. These chemicals were supplied by Sigma Chemical Company. The chemical instability of caffeate, protocatechuate, and chlorogenate demanded that plates containing these carbon sources be prepared within 24 h of use. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was obtained as a frozen suspension from Gibco BRL. E. coli cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (53) broth at 37°C. Growth media were supplemented as required with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin(100 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter strains | ||

| ADP1 | Wild type (also known as Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413) | 31 |

| ADP230 | ΔpcaBDK1 | 10 |

| ADP1027 | ΔhcaC1 (spontaneous 100-bp deletion in hcaC) | This study |

| ADP9500 | ΔpobA-hcaG1 (1,126-bp deletion between most distant MfeI sites of pobA and hcaG) | This study |

| ADP9501 | ΔhcaG2 (518-bp designed chromosomal deletion in hcaG) | This study |

| ADP9502 | hcaF1::Kmr (Kmr from pRME1 in EcoRV site of hcaF) | This study |

| ADP9503 | ΔhcaF2 (155-bp chromosomal deletion) | This study |

| ADP9504 | hcaD1::Kmr (Kmr from pRME1 in MfeI site of hcaD) | This study |

| ADP9510 | hcaG3::T7 · TAG (T7 · TAG fused in frame to 3′ end of hcaG) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-3Zf(+) | Ampr | Promega |

| pRME1 | Kmr | 21 |

| pZR3 | 2,754-bp HindIII fragment containing wild-type pcaBDK | 16 |

| pZR400 | 13.5-Kb insert in pUC18 containing pobAR and DNA downstream from pobA | 13 |

| pZR9500 | PstI-XhoI fragment from pZR400 in pGEM-3Zf(+) | This study |

| pZR9501 | 3,135-bp XhoI-HindIII fragment from pZR9500 in pGEM-3Zf(+) | This study |

| pZR9502 | 3,045-bp HindIII fragment from pZR9500 in pGEM-3Zf(+) | This study |

| pZR9503 | 1,714-bp HindIII fragment from pZR9500 in pGEM-3Zf(+) | This study |

| pZR9507 | pZR9501 containing ΔpobA-hcaG1 | This study |

| pZR9508 | pZR9502 containing hcaD::Kmr (Kmr in MfeI site in hcaA) | This study |

| pZR9509 | pZR9501 containing hcaF1::Kmr | This study |

DNA manipulation.

General previously described procedures (53) were used for manipulation of DNA. Instructions from Bio-Rad were followed when InstaGene matrix was used to isolate chromosomal DNA and for PCR. PCR mixtures (50 μl) used to amplify DNA for sequencing contained 2 μl of supernatant liquid separated from the InstaGene matrix as a template, 2 U of Pfu polymerase (Stratagene), 10 pmol of each primer, 10 pmol of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and buffer. Amplification was carried out for 30 cycles under the following conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 56°C for 45 s, and elongation at 72°C for 90 s. There was a final extension step consisting of 10 min at 72°C. Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli either by alkaline lysis (5) or with Qiaprep columns (Qiagen).

Cloning of hca genes.

Plasmid pZR400 containing pobA and DNA downstream of this gene was prepared as part of an earlier investigation (2). An XhoI-PstI subclone of pZR400 was prepared in pGEM 3Zf(+) (Promega), and the resulting plasmid was designated pZR9500 (Table 1; Fig. 2). Subsequent characterization of this plasmid and other plasmids containing Acinetobacter DNA revealed that during preparation of pZR9500 a separate chromosomal fragment had been ligated into an EcoRI site 8,220 bp downstream from the XhoI site (D. Parke, unpublished data). Therefore, the rest of the present investigation was directed to DNA from the XhoI-EcoRI segment of the chromosome (Fig. 2).

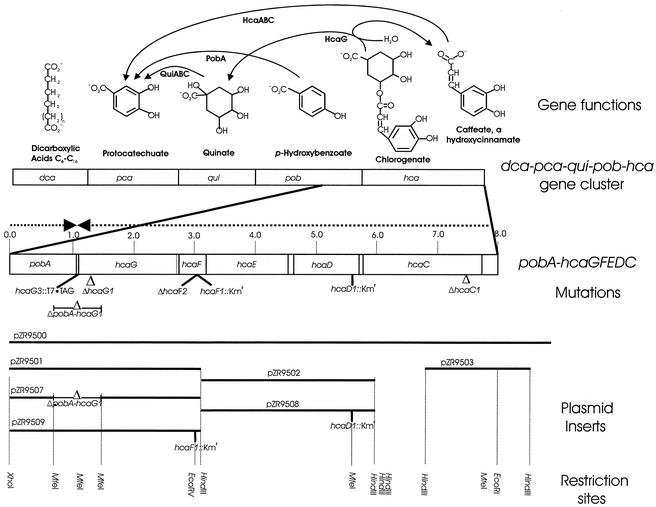

FIG. 2.

Genetic characterization of Acinetobacter hca genes associated with hydroxycinnamate catabolism. The newly discovered hca genes extend downstream from pobA in the dca-pca-qui-pob-hca cluster. As described here, HcaG hydrolyzes chlorogenate to quinate and caffeate. Metabolism of quinate to protocatechuate requires the qui genes, and HcaC initiates caffeate catabolism by converting the compound to its thioester. Upstream from hcaC and translated in the same direction is a 486-bp segment of an open reading frame encoding an aldehyde dehydrogenase. The complete open reading frame (hcaB) and an open reading frame designated hcaA have been shown in a separate study (Parke, unpublished) to encode genes for functions that complete the conversion of caffeate to protocatechuate. The locations of mutations used to identify functions of hca genes are indicated, as are the locations of plasmid inserts and restriction sites that were used for genetic construction.

DNA sequencing.

Acinetobacter DNA was sequenced from the pZR9500 insert, and PCR products were generated from the Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 chromosome under standard conditions. All PCR products were gel purified by using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A primer walking strategy was utilized for sequencing the previously uncharacterized DNA. Sequencing reactions were performed by the Yale Keck Biotechnology Resource Laboratory.

Engineering of deletion mutants.

Donor DNA containing designed mutations altering hcaG were selected in strain ADP9500 (ΔpobA-hcaG1), which contains a deletion extending from pobA into hcaG (Fig. 2). Donor fragments contained the deleted portion of pobA and an engineered mutation in hcaG. Selection for pobA function yielded recombinants containing the hcaG mutation.

The ΔpobA-hcaG1 deletion was created by removing two MfeI fragments from pZR9501; these fragments comprised a 1,126-bp region spanning the 3′ end of pobA and the 3′ end of hcaG (Fig. 2). The resulting plasmid, pZR9507, was used to transform ADP230 (ΔpcaBDK1). Transformants were selected by using mineral medium plates supplemented with 5 mM p-hydroxybenzoate and 10 mM succinate (Fig. 1). Colonies arising on these plates were struck for single colonies on 10 mM succinate. InstaGene-isolated template was used in PCR to confirm that the deletion plasmid had recombined into the chromosome. The ΔpcaBDK1 deletion was replaced with wild-type DNA from pZR3 (20), and this was followed by selection for growth with protocatechuate. A transformant emerging from this selection was designated strain ADP9500 and was used as a recipient in further selections.

The deletion mutation ΔhcaG1 was prepared by ligation of amplicons AB and CD to form ABCD, which was further amplified by PCR (Table 2). All PCR were carried out in 100-μl mixtures containing a 1:100 dilution of plasmid pZR9500 DNA as the template, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, each primer at a concentration of 1 μM, 5 U of Pfu polymerase (Stratagene Inc., La Jolla, Calif.), and 1× reaction buffer. The reactions were performed for 25 cycles consisting of 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 56°C for 60 s, and extension at 76°C for 90 s, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 9 min. Following gel purification, 5 μl of each PCR product was phosphorylated at 37°C for 30 min in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 1 mM ATP, 50 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), and 1× reaction buffer. Prior to the addition of polynucleotide kinase, the reactants were heated at 70°C for 5 min. Following phosphorylation, ligation was carried out in a 15-μl mixture containing 5 μl of each kinase reaction mixture, 1× buffer, and 600 U of T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) for 15 min at room temperature. The deletion construct was amplified from 1 μl of the ligation reaction mixture, and all other parameters were the same as those used to generate the products used for ligation. PCR products from the reaction in which the ligation mixture was used as the template were electrophoresed on a 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gel. A single band corresponding to the desired construct was purified and used as donor DNA for a transformation in which ADP9500 was the recipient and selection for growth with p-hydroxybenzoate was imposed. The identity of the engineered deletion mutation ΔhcaG1 in transformant strains was confirmed by sequence analysis, and the growth properties of one of the transformants, strain ADP9501 (Table 1), were examined.

TABLE 2.

Primers and amplicons

| Primer or amplicon | Strand | Positiona | Sequence or modificationb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primers | |||

| A | + | 400-418 | 5′-GCCGATGTGCCGCCTGTGG-3′ |

| B | − | 1743-1760 | 5′-CCGGGATTACTTGGCAGC-3′ |

| C | + | 2279-2291 | 5′-CATAACCATAGTTGATGCGAG-3′ |

| D | − | 2840-2857 | 5′-CATAAATTCAGGCATAAGG-3′ |

| E | + | 3013-3034 | 5′-GGTCAGATTAATCGTCGTGGC-3′ |

| F | − | 3630-3648 | 5′-GGTGGTGAAACAGGACTGC-3′ |

| G | − | 1069-1089 | 5′-AAAAAAGAATTCTAACACAGCCGAGATAAAAAAG-3′b |

| H | + | 1092-1110 | 5′-TTTTTTGAATTCTAACCCATTTGCTGTCCACCAGTCATGCTAGCCATTTTACAAGTGAAATTCTCG-3′b |

| Amplicons | |||

| AB | 400-1760 | ||

| CD | 2279-2857 | ||

| ABCD | 400-2857 | 518 bp deleted between positions 1760 and 2279 (residues 956 to 1475 in hcaG) | |

| EF | 3013-3630 | ||

| CDEF | 2279-3630 | 115 bp deleted between positions 2857 and 3013 (residues 230 to 386 in hcaF) | |

| AG | 400-1089 | Contains poly(A) leader and EcoRI site | |

| HB | 1092-2297 | Contains poly(T) leader and EcoRI site | |

| AGHB | 400-2297 | Encodes T7 · TAG fused to C terminus of hcaG |

Position relative to XhoI site in pobA.

The chromosomal sequence is indicated by boldface type, the EcoRI sequence is italicized, and the T7·TAG sequence is underlined.

Similar conditions were used to generate strain ADP9503 (ΔhcaF2). Amplicons CD and EF (Table 2) were ligated, and the product was amplified to form the PCR product CDEF containing ΔhcaF2. This DNA was used to transform strain ADP9502 (hcaF1::Kmr), and the resulting population was screened for kanamycin-sensitive strains. The designed ΔhcaF2 deletion in one of these organisms, strain ADP9503, was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

Insertion mutations.

The Kmr marker from pRME1 was introduced into the EcoRV site of pZR9501, giving rise to pZR9509 (Fig. 2). This plasmid, linearized with HindIII, was used to transform strain ADP1, and this was followed by selection for kanamycin resistance. Sequencing of a transformant, strain ADP9502, demonstrated that it had acquired hcaF1::Kmr. Similarly, the Kmr marker from pRME1 was introduced into the MfeI site of pZR0502, creating pZR9508 (Fig. 2). Transformation of strain ADP1 with linearized DNA from the latter plasmid gave rise to strain ADP9504 (Table 1), which was selected in the presence of kanamycin. Sequencing of the DNA from this strain demonstrated that it contained hcaD1::Kmr.

Preparation of strain ADP9510 (hcaG3::T7 · TAG).

A T7 · TAG marker was fused to the carboxy terminus of HcaG so that the protein could be detected immunologically as a T7 · TAG horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.). Primers A and G were used to prepare the amplicon AG; primers B and H were used to prepared the amplicon BH (Table 2). After restriction with EcoRI, the amplicons were ligated to form amplicon AGHB, which contained T7 · TAG ligated to the carboxy terminus of HcaG (Table 2). After amplification with primers A and B, the AGHB DNA was used to transform strain ADP9500. A resulting transformant, strain ADP9510, was selected on p-hydroxybenzoate. This organism grew on chlorogenate and expressed hcaG3::T7 · TAG inducibly. Sequencing demonstrated that the T7 · TAG was in the predicted chromosomal location.

SDS-PAGE and immunodetection of HcaG::T7 · TAG.

Strain ADP9510 (hcaG3::T7 · TAG) was grown to a concentration of about 5 × 108 cells per ml and harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 5 min. Centrifuged cells were suspended in 10 mM Na2KPO4 buffer (pH 7.0) and sonicated. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation of the sonicated material at 5,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant liquid was filtered through a 2-μm-pore-size membrane. Protein concentrations were measured by the method of Bradford by using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed as described by Laemmli (33) with a Bio-Rad mini-slab gel apparatus. Proteins from the SDS-PAGE gels were transferred to nitrocellulose by capillary action in blotting buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM glycine, 20% methanol; pH 8.3) for no less than 24 h. Proteins transferred to the nitrocellulose were immunostained by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated T7 · TAG antibody (Novagen) and the SuperSignal substrate (Novagen) and following the instructions of the manufacturer, which also supplied Perfect Protein Western Markers as molecular weight markers.

Separation of soluble and membrane-associated fractions.

Chlorogenate-grown cultures of ADP9510 were centrifuged, resuspended in 10 mM Na2KPO4 buffer (pH 7.0), and sonicated. Whole cells were removed by centrifugation for 20 min at 5,000 × g, followed by filtration through a 2-μm-pore-size filter. The filtrate was centrifuged at 110,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant liquid was removed, and the pellet was suspended in a volume equal to that of the removed supernatant liquid.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence of the hca genes from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. L05770. It should be noted that the designation ech has been assigned to the structural gene for enoyl-CoA hydratase lyase and the designation fcs has been assigned to the feruloyl-CoA ligase gene (1). As shown here and elsewhere (Parke, unpublished), Acinetobacter genes with these functions are closely clustered in what may prove to be a single transcript generally associated with hydroxycinnamate catabolism. The designation hca has been assigned to this transcript; hcaA is the designation for the structural gene for enoyl-CoA hydratase lyase (Parke, unpublished), and hcaC is the designation for the structural gene for hydroxycinnamate-CoA ligase.

RESULTS

Selection and properties of mutant strain ADP1027 (ΔhcaC1) lacking a CoA ligase required for growth with hydroxycinnamic acids.

Exposure of 108 cells from an overnight culture of strain ADP230 (ΔpcaBDK1) to 3 mM caffeate in plates containing 10 mM succinate produced about 100 colonies on each plate. After purification by streaking on succinate plates, some of the mutants grew with succinate in the presence of caffeate but not in the presence of protocatechuate. It seemed likely that these strains were blocked in the conversion of caffeate to protocatechuate, and this possibility was tested by replacing ΔpcaBDK1 in one of the strains with wild-type DNA and examining the growth properties of the resulting organism, strain ADP1027 (Table 1). This strain used p-hydroxybenzoate as a growth substrate and failed to grow at the expense of caffeate, p-coumarate, ferulate, or 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate (Fig. 1).

Plasmid pZR400 is known to contain pobA and a segment of DNA downstream from this gene (13). The subclone pZR9500 (Table 1) contains a portion of pobA and the previously uncharacterized downstream DNA. Transformation of strain ADP1027 with linearized pZR9500 produced recombinants that grew with caffeate. Therefore, it was evident that the gene inactivated in strain ADP1027 is part of the insert in pZR9500 and is linked to pobA. Sequencing of DNA downstream from pobA in pZR9500 revealed five complete open reading frames designated hcaC, hcaD, hcaE, hcaF, and hcaG (Fig. 2; Table 3). Transformation of strain ADP1027 with subclone pZR9503 (Fig. 2) showed that the mutation is within an open reading frame designated hcaC. Sequencing the corresponding portion of the mutant strain ADP1027 chromosome revealed that the selected spontaneous hcaC1 mutation is a 100-bp deletion extending from the sequence ACATT at position 702 to ACATT beginning at position 802 in the gene.

TABLE 3.

Genes in the sequenced hca region

| Gene | Strand | Position | Deduced function |

|---|---|---|---|

| hcaC | − | 5830-7710 | Hydroxycinnamate lyase |

| hcaD | − | 4621-5760 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| hcaE | − | 3295-4530 | Porin |

| hcaF | − | 2854-3243 | Unknown |

| hcaG | − | 1089-2831 | Chlorogenate esterase |

| pobA | + | 1-1041 | p-Hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase |

The deduced primary structure of HcaC corresponds to a protein containing 626 amino acids and exhibiting 53% sequence identity with feruloyl-CoA ligase from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 (47). The growth properties of strain ADP1027 indicate that the Acinetobacter CoA ligase encoded by hcaC initiates metabolism of caffeate, p-coumarate, ferulate, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate by converting the compounds to the corresponding thioesters (Fig. 1).

Strain ADP9504 (hcaD1::Kmr) lacks an acyl-CoA dehydrogenase required for conversion of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionyl-CoA to caffeoyl-CoA.

HcaD is a 379-amino-acid protein that is a member of a large family of flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. The knockout mutation hcaD1::Kmr prevented growth with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate and allowed growth with caffeate. Since the hcaC-encoded CoA ligase is required for growth with both compounds, it is likely that HcaD oxidizes the saturated propionyl-CoA side chain of phenylpropanoyl thioesters (Fig. 1).

HcaE resembles VanP, a porin associated with vanillate metabolism in Acinetobacter.

HcaE is a 416-amino-acid protein that in primary structure most closely resembles Acinetobacter VanP (9, 56). These proteins exhibit 44% identity over a 314-residue sequence and, as judged by primary structure, are members of a large family of porins, including a well-studied group from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24). Thus, two porin genes are linked to genes associated with ferulate catabolism in Acinetobacter; one porin gene is part of the hca cluster, and the other porin gene is associated with the van genes for conversion of vanillate, a product of ferulate, to protocatechuate (Fig. 1). The van genes are exceptional in that they occupy a genetically unstable locus far from all of the other genes required for complete catabolism of ferulate (56). In light of the structural similarity of ferulate and vanillate, it seemed likely that multiple knockout mutations would be required in order to observe the possible contributions of vanP and hcaE to ferulate metabolism, so genetic analysis of hcaE was not included as part of this study.

A knockout mutation in hcaF confers no discernible phenotype.

Sequence comparisons revealed few matches for the 129-amino-acid protein predicted to be encoded by hcaF. The closest matches are with proteins with unknown functions from Brucella and Caulobacter. Knockouts caused by hcaF1::Kmr and ΔhcaF2 had no discernible effect on catabolism of hydroxycinnamates, so the function of hcaF remains unknown.

Properties of strain ADP9501 (ΔhcaG2) lacking an esterase required for hydrolysis of chlorogenate to quinate and caffeate.

The amino acid sequence of HcaG exhibits 29 and 27% identity to the deduced primary structures of a tannase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (60) and a feruloyl esterase from A. niger (12), respectively. A likely function for HcaG was inferred from the location of its structural gene between other hca genes required for caffeate catabolism and the qui genes associated with quinate catabolism in Acinetobacter (Fig. 2). Since hydrolysis of chlorogenate produces caffeate and quinate (Fig. 2), it seemed likely that HcaG is chlorogenate esterase. This supposition was confirmed by demonstration that the knockout mutation ΔhcaG1 eliminated the ability of Acinetobacter to grow with chlorogenate while it left the ability to grow with caffeate or quinate intact. Mutations blocking hcaF (Table 1) did not prevent growth with chlorogenate.

Regulation of chlorogenate esterase (HcaG) synthesis by intracellular catabolites and evidence that the enzyme is membrane associated.

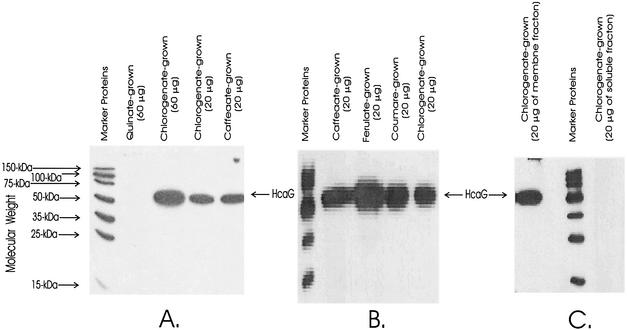

An interesting feature of the chlorogenate esterase reaction is that one of its products, quinate, is metabolized outside the inner cell membrane (9), whereas the other product, caffeate, presumably is metabolized intracellularly through the thioester intermediate. This raised the possibility that the esterase acts upon chlorogenate in the inner cell membrane and that chlorogenate does not enter cells. This consideration, coupled with the observation that hcaG is in a position where it may be cotranscribed with other hca genes, suggested that the inducer of chlorogenate esterase might be either caffeate or an intracellular catabolite formed from chlorogenate. The protein was determined by using mutant strain ADP9510 (hcaG3::T7 · TAG), which produces HcaG with an epitope tag fused to its carboxyl terminus. As judged by growth properties, the in vivo activity of the mutant was unimpaired by the fusion, and the esterase protein was detected immunochemically in cell extracts. As shown in Fig. 3, HcaG3::T7 · TAG was not induced by growth with quinate. Growth with chlorogenate, caffeate, ferulate, or coumarate induced the enzyme (Fig. 3). An indication that metabolism of caffeate may be necessary for induction of HcaG emerged from the observation that mutant strain ADP1027 (ΔhcaC1), which was unable to form caffeoyl-CoA from caffeate, did not grow with chlorogenate.

FIG. 3.

Induction and cellular location of chlorogenate esterase detected as HcaG3::T7 · Tag in cell extracts (A and B) and in a membrane preparation (C). The amount of protein separated by SDS-PAGE in each lane is indicated. Immunoblots show the presence of the esterase in extracts of cells grown with chlorogenate, caffeate, ferulate, and coumarate (A and B) but not in extracts of cells grown with quinate (A). The esterase was associated with the membrane fraction of cell extracts (C).

The inference that chlorogenate esterase (HcaG) is membrane associated was explored by testing for the presence of HcaG3::T7 · TAG in soluble and membrane fractions separated from extracts of chlorogenate-grown cultures of strain ADP9510. As shown in Fig. 3C, HcaG protein was strongly represented in the membrane fraction and undetectable in the soluble fraction.

DISCUSSION

Gene organization and the natural environment.

The nutritional versatility of microorganisms has been examined most frequently and most conveniently by individual presentation of potential growth substrates. Such studies have resulted in valuable conclusions about how shared sets of common nutrients help to define microbial taxa. Left unanswered are questions about where and how the nutrients are encountered by the microorganisms in their natural environments. Curiously, some clues in this regard have emerged from studies of chromosomal gene organization. A tendency towards clustering of bacterial genes for related catabolic functions has been known for some time (35, 52), and two large clusters have been identified in the chromosome of Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. One of these, the sal-are-ben-cat cluster (28, 29), encodes enzymes that metabolize a range of aromatic acids, alcohols, and esters through catechol and the β-ketoadipate pathway.

Our knowledge concerning the other large cluster, containing the dca-pca-qui-pob genes, was expanded to include hca genes through this investigation. Most of the dca-pca-qui-pob-hca genes contribute to metabolism of aromatic (2, 15) and hydroaromatic (17) compounds through protocatechuate, but the dca genes (48) encode enzymes that act upon straight-chain dicarboxylic acids by independent metabolic pathways (Fig. 2). A shared characteristic of all the genes is that they encode pathways for catabolism of compounds that are produced by plants in response to stress. In particular, the dicarboxylic acids and hydroxyaromatic acids are components of the protective plant polymer suberin (4, 23, 38, 61). Hydroxycinnamate compounds serve additional protective roles, such as the contribution of ferulate in forming a “molecular spot weld” (32) in response to physical damage. This grouping of functions warranted the initial examination of cloned DNA extending downstream from pobA for the gene inactivated by the spontaneous ΔhcaC1 mutation blocking conversion of a hydroxycinnamate, caffeate, to protocatechuate. The requirement for hcaC for metabolism of ferulate, coumarate, and 3,4-dihyroxypropioniate shows that the CoA ligase encoded by the gene has specificity broad enough to encompass common hydroxycinnamates. Breadth of specificity also is exhibited by plant hydroxycinnamate-CoA ligases, which are commonly designated coumarate CoA ligases (25, 34, 36, 57). Interest in the production of vanillin from ferulate has directed attention to microbial ferulate CoA ligases (1, 19, 40, 47, 58), although these enzymes act upon a range of hydroxycinnamates (40). Where breadth of specificity has been established and is known to contribute to biological function, it might be preferable to refer to such enzymes as hydroxycinnamate CoA ligases.

Downstream from hcaC is hcaD encoding a protein corresponding to a member of an acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family of enzymes. Inactivation of hcaD prevents growth with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate (Fig. 1). Since hcaC also is required for metabolism of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionate, the overall findings are consistent with the hypothesis that HcaC has a specificity broad enough to allow formation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylpropionyl-CoA, the substrate for the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (Fig. 1). The genetic location of the HcaD gene suggests that hydroxycinnamates and their derivatives with saturated side chains may serve as companion nutrients for organisms related to Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 in their natural environments.

The chromosomal location of hcaG between the qui (quinate) and hca (hydroxycinnamate) genes for catabolism of its products (quinate and caffeate) provided an essential clue in determining the function of HcaG, which proved to be chlorogenate esterase. Had hcaG been located elsewhere on the chromosome, the effect of a knockout hcaG mutation on chlorogenate metabolism would not have been tested. Does chlorogenate accompany the hydroxycinnamates that combine to provide nutrition for Acinetobacter strain sp. strain ADP1 and related organisms in the natural environment? This possibility is heightened by evidence that hydroxycinnamate metabolism induces chlorogenate esterase. Growth with hydroxycinnamates alone would cause gratuitous synthesis of the esterase.

Left unanswered by this investigation is the range of chlorogenate substrates that are hydrolyzed by HcaG. This information, coupled with information about the distribution of chlorogenic acids in different plant sources (6, 42, 49, 59), might provide greater insight into the niche occupied by Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. The inference that hydroxycinnamates help to define the niche of the organism comes from the observation that the organism does not grow with tyrosine, a common amino acid that could be converted by a single enzyme (tyrosine ammonia lyase) to coumarate, a hydroxycinnamate that supports robust growth of the strain. In this sense, the organism is a nutritional specialist that is dependent upon plant products and seemingly eschews the opportunity to be a generalist which is capable of growth with a compound found in all living things.

Another question, not addressed here, is the mechanism by which the two-carbon fragment is removed from the side chain of hydroxycinnamyl thioesters during their metabolism. In another investigation, Parke (unpublished) has shown that, as reported in studies with other bacteria (1, 19, 41, 50), a hydratase/lyase cleaves the thioesters, forming the corresponding aldehydes and acetyl-CoA in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Ferulate is catabolized through vanillate in this organism (56).

Cellular location of chlorogenate esterase.

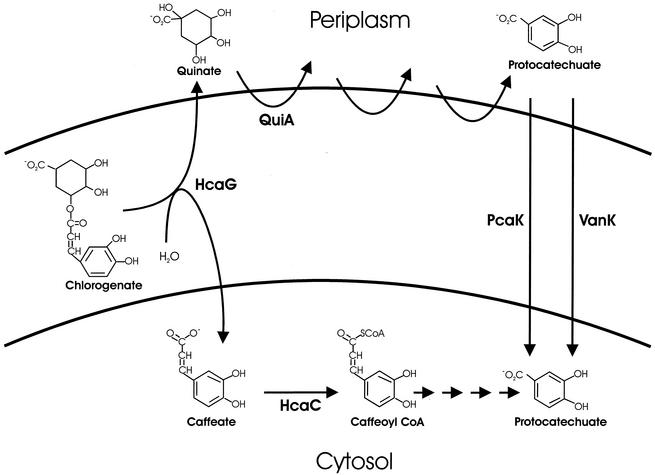

Chlorogenate esterase synthesis may or may not be physiologically burdensome, but its demands certainly are complex. One product of the enzyme, quinate, is metabolized outside the inner cell membrane (9), whereas the other product, caffeate, is metabolized at an intracellular location, as indicated by the requirement for CoA (Fig. 4). The simplest interpretation of this finding is that chlorogenate esterase is located within the inner cell membrane so that quinate is produced on one side and caffeate is produced on the other (Fig. 4). Alternatively, quinate and caffeate may be produced in the periplasm, followed by transport of the caffeate across the inner cell membrane. Consistent with both interpretations is the apparent location of the epitope-tagged enzyme (HcaG3::T7 · TAG) in the membrane fraction of cell extracts (Fig. 3).

FIG. 4.

Cellular location of chlorogenate esterase. The products of the enzyme are metabolized on different sides of the intracellular membrane. QuiA initiates a sequence of reactions that convert quinate to protocatechuate on the outer surface of the membrane. Specific transport systems transfer protocatechuate to the cytosol (9). Metabolism of caffeate in the cystosol is initiated by HcaC, which converts the compound to a thioester of CoA.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grant DAAG55-98-1-0232 from the Army Research Office and by grant MCB-9603980 from the National Science Foundation to L.N.O. M.A.S. received support from the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies.

We thank Donna Parke for providing essential information about hca genes that were inaccessible in the present investigation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achterholt, S., H. Priefert, and A. Steinbüchel. 2000. Identification of Amycolatopsis sp. strain HR167 genes, involved in the bioconversion of ferulic acid to vanillin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 54:799-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Averhoff, B., L. Gregg-Jolly, D. Elsemore, and L. N. Ornston. 1992. Genetic analysis of supraoperonic clustering by use of natural transformation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 174:200-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernards, M. A., and N. Lewis, G. 1998. The macromolecular aromatic domain in suberized tissue: a changing paradigm. Phytochemistry 47:915-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernards, M. A., and F. A. Razem. 2001. The poly(phenolic) domain of potato suberin: a non-lignin cell wall bio-polymer. Phytochemistry 57:1115-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clifford, M. N. 2000. Chlorogenic acids and other cinnamates—nature, occurrence, dietary burden, absorption and metabolism. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80:1033-1043. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couteau, D., A. L. McCartney, G. R. Gibson, G. Williamson, and C. B. Faulds. 2001. Isolation and characterization of human colonic bacteria able to hydrolyse chlorogenic acid. J. Appl. Microbiol. 90:873-881. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.D'Argenio, D. A., A. Segura, P. V. Bunz, and L. N. Ornston. 2001. Spontaneous mutations affecting transcriptional regulation by protocatechuate in Acinetobacter. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Argenio, D. A., A. Segura, W. M. Coco, P. V. Bunz, and L. N. Ornston. 1999. The physiological contribution of Acinetobacter PcaK, a transport system that acts upon protocatechuate, can be masked by the overlapping specificity of VanK. J. Bacteriol. 181:3505-3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Argenio, D. A., M. W. Vetting, D. H. Ohlendorf, and L. N. Ornston. 1999. Substitution, insertion, deletion, suppression, and altered substrate specificity in functional protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 181:6478-6487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delneri, D., G. Degrassi, R. Rizzo, and C. V. Bruschi. 1995. Degradation of trans-ferulic and p-coumaric acid by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus DSM 586. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1244:363-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vries, R. P., P. A. VanKuyk, H. C. M. Kester, and J. Visser. 2002. The Aspergillus niger faeB gene encodes a second feruloyl esterase involved in pectin and xylan degradation and is specifically induced in the presence of aromatic compounds. Biochem. J. 363:377-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMarco, A. A., B. Averhoff, and L. N. Ornston. 1993. Identification of the transcriptional activator pobR and characterization of its role in the expression of pobA, the structural gene for p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 175:4499-4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiMarco, A. A., B. A. Averhoff, E. E. Kim, and L. N. Ornston. 1993. Evolutionary divergence of pobA, the structural gene encoding p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase in an Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain well-suited for genetic analysis. Gene 125:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiMarco, A. A., and L. N. Ornston. 1994. Regulation of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase synthesis by PobR bound to an operator in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 176:4277-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doten, R. C., K. L. Ngai, D. J. Mitchell, and L. N. Ornston. 1987. Cloning and genetic organization of the pca gene cluster from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 169:3168-3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsemore, D. A., and L. N. Ornston. 1994. The pca-pob supraoperonic cluster of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus contains quiA, the structural gene for quinate-shikimate dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 176:7659-7666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elsemore, D. A., and L. N. Ornston. 1995. Unusual ancestry of dehydratases associated with quinate catabolism in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 177:5971-5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gasson, M. J., Y. Kitamura, W. R. McLauchlan, A. Narbad, A. J. Parr, E. L. H. Parsons, J. Payne, M. J. C. Rhodes, and N. J. Walton. 1998. Metabolism of ferulic acid to vanillin. A bacterial gene of the enoyl-SCoA hydratase/isomerase superfamily encodes an enzyme for the hydration and cleavage of a hydroxycinnamic acid SCoA thioester. J. Biol. Chem. 273:4163-4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerischer, U., and L. N. Ornston. 1995. Spontaneous mutations in pcaH and -G, structural genes for protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 177:1336-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gielow, A., L. Diederich, and W. Messer. 1991. Characterization of a phage-plasmid hybrid (phasyl) with two independent origins of replication isolated from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:73-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Perez, S., K. B. Merck, J. M. Vereijken, G. A. van Koningsveld, H. Gruppen, and A. G. J. Voragen. 2002. Isolation and characterization of undenatured chlorogenic acid free sunflower (Helianthus annuus) proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50:1713-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graca, J., and H. Pereira. 2000. Suberin structure in potato periderm: glycerol, long-chain monomers, and glyceryl and feruloyl dimers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48:5476-5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancock, R. E. W., and F. S. L. Brinkman. 2002. Function of Pseudomonas porins in uptake and efflux. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:17-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harding, S. A., J. Leshkevich, V. L. Chiang, and C. J. Tsai. 2002. Differential substrate inhibition couples kinetically distinct 4-coumarate:coenzyme a ligases with spatially distinct metabolic roles in quaking aspen. Plant Physiol. 128:428-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartnett, G. B., B. Averhoff, and L. N. Ornston. 1990. Selection of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus mutants deficient in the p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase gene (pobA), a member of a supraoperonic cluster. J. Bacteriol. 172:6160-6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikonen, A., J. Tahvanainen, and H. Roininen. 2002. Phenolic secondary compounds as determinants of the host plant preferences of the leaf beetle, Agelastica alni. Chemoecology 12:125-131. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones, R. M., L. S. Collier, E. L. Neidle, and P. A. Williams. 1999. areABC genes determine the catabolism of aryl esters in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 181:4568-4575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones, R. M., V. Pagmantidis, and P. A. Williams. 2000. sal genes determining the catabolism of salicylate esters are part of a supraoperonic cluster of catabolic genes in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 182:2018-2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juni, E. 1972. Interspecies transformation of Acinetobacter: genetic evidence for a ubiquitous genus. J. Bacteriol. 112:917-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juni, E., and A. Janik. 1969. Transformation of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Bacterium anitratum). J. Bacteriol. 98:281-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroon, P. A., M. T. Garcia-Conesa, I. J. Fillingham, G. P. Hazlewood, and G. Williamson. 1999. Release of ferulic acid dehydrodimers from plant cell walls by feruloyl esterases. J. Sci. Food Agric. 79:428-434. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, D., and C. J. Douglas. 1996. Two divergent members of a tobacco 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase (4CL) gene family. cDNA structure, gene inheritance and expression, and properties of recombinant proteins. Plant Physiol. 112:193-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leidigh, B. J., and M. L. Wheelis. 1973. The clustering on the Pseudomonas putida chromosome of genes specifying dissimilatory functions. J. Mol. Evol. 2:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindermayr, C., B. Mollers, J. Fliegmann, A. Uhlmann, F. Lottspeich, H. Meimberg, and J. Ebel. 2002. Divergent members of a soybean (Glycine max L.) 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase gene family. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:1304-1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukaszewicz, M., I. Matysiak-Kata, A. Aksamit, J. Oszmianski, and J. Szopa. 2002. 14-3-3 protein regulation of the antioxidant capacity of transgenic potato tubers. Plant Sci. 163:125-130. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lulai, E. C., and D. L. Corsini. 1998. Differential deposition of suberin phenolic and aliphatic domains and their roles in resistance to infection during potato tuber (Solanum tuberosum L.) wound-healing. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 53:209-222. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maher, E. A., N. J. Bate, W. T. Ni, Y. Elkind, R. A. Dixon, and C. J. Lamb. 1994. Increased disease susceptibility of transgenic tobacco plants with suppressed levels of preformed phenylpropanoid products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7802-7806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masai, E., Y. Harada, and X. Peng. 2002. Cloning and characterization of the ferulic acid catabolic genes of Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4416-4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitra, A., Y. Kitamura, M. J. Gasson, A. Narbad, A. J. Parr, J. Payne, M. J. Rhodes, C. Sewter, and N. J. Walton. 1999. 4-Hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA hydratase/lyase (HCHL)—an enzyme of phenylpropanoid chain cleavage from Pseudomonas. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 365:10-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moelgaard, P., and H. Ravn. 1988. Evolutionary aspects of caffeoyl ester distribution in dicotolydens. Phytochemistry 27:2411-2421. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morawski, B., A. Segura, and L. N. Ornston. 2000. Substrate range and genetic analysis of Acinetobacter vanillate demethylase. J. Bacteriol. 182:1383-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narbad, A., and M. J. Gasson. 1998. Metabolism of ferulic acid via vanillin using a novel CoA-dependent pathway in a newly-isolated strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Microbiology 144:1397-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okamura, S., and M. Watanabe. 1982. Measurement of hydroxycinnamate acid ester hydrolase by the change of UV absorption. Agric. Biol. Chem. 46:297-299. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okamura, S., and M. Watanabe. 1982. Purification and properties of hydroxycinnamic acid hydrolase from Aspergillus japonicum. Agric. Biol. Chem. 46:1839-1848. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Overhage, J., H. Priefert, and A. Steinbüchel. 1999. Biochemical and genetic analyses of ferulic acid catabolism in Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4837-4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parke, D., M. A. Garcia, and L. N. Ornston. 2001. Cloning and genetic characterization of dca genes required for β-oxidation of straight-chain dicarboxylic acids in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4817-4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parr, A. J., and G. P. Bolwell. 2000. Phenols in the plant and in man. The potential for possible nutritional enhancement of the diet by modifying the phenols content or profile. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80:985-1012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plaggenborg, R., A. Steinbüchel, and H. Priefert. 2001. The coenzyme A-dependent, non-β-oxidation pathway and not direct deacetylation is the major route for ferulic acid degradation in Delftia acidovorans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosazza, J. P., Z. Huang, L. Dostal, T. Volm, and B. Rousseau. 1995. Review: biocatalytic transformations of ferulic acid: an abundant aromatic natural product. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15:457-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg, S. L., and G. D. Hegeman. 1969. Clustering of functionally related genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 99:353-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sambrook, J., and D. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 54.Schöbel, B., and W. Pollmann. 1980. Further characterization of a chlorogenic acid hydrolase from Aspergillus niger. Z. Naturforsch. Sect. C J. 35:699-701. [PubMed]

- 55.Schöbel, B., and W. Pollmann. 1980. Isolation and characterization of a chlorogenic acid esterase from Aspergillus niger. Z. Naturforsch Sect. C 35:209-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Segura, A., P. V. Bunz, D. A. D'Argenio, and L. N. Ornston. 1999. Genetic analysis of a chromosomal region containing vanA and vanB, genes required for conversion of either ferulate or vanillate to protocatechuate in Acinetobacter. J. Bacteriol. 181:3494-3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stuible, H. P., and E. Kombrink. 2001. Identification of the substrate specificity-conferring amino acid residues of 4-coumarate:coenzyme A ligase allows the rational design of mutant enzymes with new catalytic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 276:26893-26897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Venturi, V., F. Zennaro, G. Degrassi, B. C. Okeke, and C. V. Bruschi. 1998. Genetics of ferulic acid bioconversion to protocatechuic acid in plant-growth-promoting Pseudomonas putida WCS358. Microbiology 144:965-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Winter, M., and K. Hermann. 1986. Esters and glucosides of hydroxycinnamic acids in vegetables. J. Agric. Food Chem. 34:616-620. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wood, D. W., J. C. Setubal, R. Kaul, D. E. Monks, J. P. Kitajima, V. K. Okura, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, G. E. Wood, N. F. Almeida, L. Woo, Y. C. Chen, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, P. D. Karp, D. Bovee, P. Chapman, J. Clendenning, G. Deatherage, W. Gillet, C. Grant, T. Kutyavin, R. Levy, M. J. Li, E. McClelland, and E. W. Nester. 2001. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2317-2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan, B., and R. E. Stark. 2000. Biosynthesis, molecular structure, and domain architecture of potato suberin: a 13C NMR study using isotopically labeled precursors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48:3298-3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]