Abstract

We describe the singular value decomposition (SVD) of yeast genome-scale mRNA lengths distribution data measured by DNA microarrays. SVD uncovers in the mRNA abundance levels data matrix of genes × arrays, i.e., electrophoretic gel migration lengths or mRNA lengths, mathematically unique decorrelated and decoupled “eigengenes.” The eigengenes are the eigenvectors of the arrays × arrays correlation matrix, with the corresponding series of eigenvalues proportional to the series of the “fractions of eigen abundance.” Each fraction of eigen abundance indicates the significance of the corresponding eigengene relative to all others. We show that the eigengenes fit “asymmetric Hermite functions,” a generalization of the eigenfunctions of the quantum harmonic oscillator and the integral transform which kernel is a generalized coherent state. The fractions of eigen abundance fit a geometric series as do the eigenvalues of the integral transform which kernel is a generalized coherent state. The “asymmetric generalized coherent state” models the measured data, where the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of most genes as well as the distribution of the peaks of these profiles fit asymmetric Gaussians. We hypothesize that the asymmetry in the distribution of the peaks of the profiles is due to two competing evolutionary forces. We show that the asymmetry in the profiles of the genes might be due to a previously unknown asymmetry in the gel electrophoresis thermal broadening of a moving, rather than a stationary, band of RNA molecules.

Keywords: DNA microarrays, yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Hermite functions, generalized coherent states, evolutionary forces

Advances in sequencing technology (1), including DNA and RNA gel electrophoresis (2–6), fueled the Human Genome Project, promoted the resulting sequencing of numerous complete genomes, and stimulated the emergence of DNA microarray hybridization technology. This high-throughput technology makes it possible to assay the hybridization of DNA or RNA molecules, extracted from a single sample, with several thousands of probes simultaneously (7, 8). Different types of molecular biological signals, such as abundance levels of DNA, RNA, and DNA-bound proteins can now be measured on genomic scales (9, 10).

Recently, Hurowitz and Brown (11) described the use of DNA microarrays in the genome-scale measurement of the distribution of the lengths of mRNA gene transcripts in yeast. Electrophoresis was used to separate the transcripts by migration length in an agarose gel, where each migration length corresponds to a transcript length. The gel was cut into slices, and the relative abundance levels of the different yeast transcripts in each slice was measured with a DNA microarray. We describe the singular value decomposition (SVD) (12) of the mRNA abundance levels data matrix of genes × arrays, i.e., gel slices, electrophoretic migration lengths, or mRNA lengths. SVD separates the measured profiles of the genes into mathematically unique decorrelated and decoupled “eigengenes,” which are the eigenvectors of the arrays × arrays correlation matrix. The corresponding series of eigenvalues are proportional to the series of “fractions of eigen abundance,” each of which indicates the significance of the corresponding eigengene relative to all eigengenes. Recently, we illustrated the possible correspondence between significant eigengenes uncovered in DNA microarray data and the independent biological and experimental processes that compose the data with an analysis of genome-scale mRNA expression from yeast during its cell cycle program (ref. 13, and see also refs. 14 and 15).

Here we show that the eigengenes of the yeast mRNA lengths distribution data fit “asymmetric Hermite functions.” Hermite functions are the eigenfunctions of the quantum harmonic oscillator (17, 18) and the integral transform which kernel is a generalized coherent state (19, 20). We show that the corresponding fractions of eigen abundance fit a geometric series, as do the eigenvalues of the integral transform which kernel is a generalized coherent state. We show that, as follows from the uniqueness of SVD, the “asymmetric generalized coherent state” model fits the measured genome-scale distribution of the lengths of mRNA gene transcripts in yeast, i.e., that (i) the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of most genes fit asymmetric Gaussians; and (ii) the distribution of the peaks of the profiles of the genes fits an asymmetric Gaussian that peaks approximately at the mRNA length of 1,000 ± 50 nucleotides. We hypothesize that the asymmetric Gaussian distribution of the peaks of the profiles of the genes is due to two competing evolutionary forces that balance at the peak of this distribution.

Recently, we predicted a previously unknown biological principle by modeling DNA microarray data. Integrating genome-scale proteins’ DNA-binding data with cell cycle mRNA expression time course data from yeast, using pseudoinverse projection, we predicted a previously unknown correlation between DNA replication initiation and RNA transcription, which might be due to an undiscovered mechanism of regulation (21). Now we reveal a previously unknown physical principle by modeling DNA microarray data. We show that the asymmetry in the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of the genes across the arrays, i.e., gel slices, might be due to a previously unknown asymmetry in the thermal broadening of a moving band of mRNA molecules. The peak of the symmetric Gaussian profile of a stationary band shifts within the moving band, changing its profile into an asymmetric Gaussian. We conclude that the mathematical modeling of DNA microarray data might be used to uncover the physical as well as the biological principles that govern the activities of DNA and RNA.

SVD of Genome-Scale mRNA Lengths Distribution in Yeast

Hurowitz and Brown (11) measured relative mRNA abundance levels for 9,867 putative genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, over a range of 60 mm of an agarose gel cut into 30 slices of 2 mm each, spanning the electrophoretic migration range of 42–100 mm and the corresponding mRNA lengths range of 4,400–300 nucleotides, after 2 h of separation by length in an electric field of 9 V/cm. The data set we analyze tabulates the ratios of mRNA abundance levels for the P = 6,776 genes with no missing data in any of the X = 30 arrays corresponding to the 30 slices of gel. Let the matrix d̂ of size P-genes × X-arrays tabulate the genome-scale mRNA lengths distribution of yeast (see www.bme.utexas.edu/research/orly/harmonic_oscillator). The vector in the pth row of the matrix d̂, 〈p|d̂〉 lists the profile of relative abundance levels of the pth gene transcript across the different gel slices which correspond to the different arrays.§ The vector in the xth column of the matrix d̂, d̂|x〉, lists the relative abundance levels of the P gene transcripts as measured in the xth gel slice by the xth array.

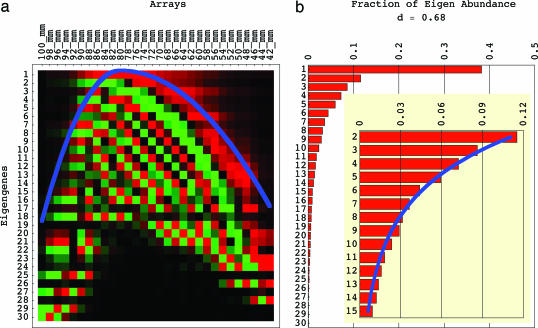

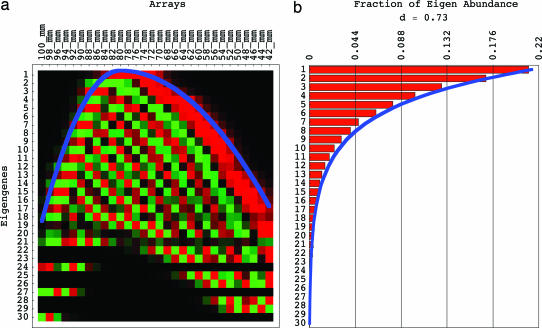

We compute the singular value decomposition (SVD) of the data matrix d̂ = ûω̂v̂T (12) (see www.bme.utexas.edu/research/orly/harmonic_oscillator). The nth row of the orthogonal transformation matrix v̂T lists the nth “eigengene” 〈n|v̂T, which is unique up to a phase factor of ±1 (13) (Fig. 1a). The diagonal nonnegative matrix ω̂ lists the “eigen abundance” levels {〈n|ω̂|n〉} (Fig. 1b). The significance of the nth eigengene is indicated by the nth “fraction of eigen abundance” Ωn = 〈n|ω̂|n〉2/(Σn=1N 〈n|ω̂|n〉2), i.e., the abundance captured by the nth eigengene relative to that captured by all eigengenes. Note that the eigengenes are the eigenvectors of the X-arrays × X-arrays correlation matrix d̂Td̂ with the corresponding series of eigenvalues proportional to the series of the fractions of eigen abundance.

Fig. 1.

Eigengenes of the yeast genome-scale mRNA lengths distribution data. (a) Raster display of v̂T, the abundance of X = 30 eigengenes in 30 arrays, corresponding to 30 gel slices, with overabundance (red), no change in abundance (black), and underabundance (green) around the “ground state” of abundance, which is captured by the first eigengene 〈1|v̂T. The inflection points of the eigengenes approximately sample a graph of the asymmetric parabolic potential kx2/2, where k = k1 for x ≤ 0 and k = k2 = k1/4 for x ≥ 0 (blue) at unit intervals. (b) Bar chart of the 30 fractions of eigen abundance {Ωn}, which approximately fit a graph of the exponential function of n, {cλn} (blue).

Eigengenes Fit “Asymmetric Hermite Functions”

The nth Hermite function,

where Hn( x) is the nth Hermite polynomial,

|

is a solution of the differential equation that describes the generalized coordinate x of the quantum harmonic oscillator (17, 18) with the generalized Hooke’s constant k,

Substituting d2[hn( x)]/dx2 = 0 in Eq. 3, it can be shown that the inflection points of the Hermite functions hn( x) sample the parabolic potential of the harmonic oscillator at unit intervals, where kx2/2 = (n + 1/2). The Hermite functions form an orthogonal basis in the range x ∈ (−∞, ∞), and are, therefore, eigenfunctions of the quantum harmonic oscillator in the generalized coordinate representation.

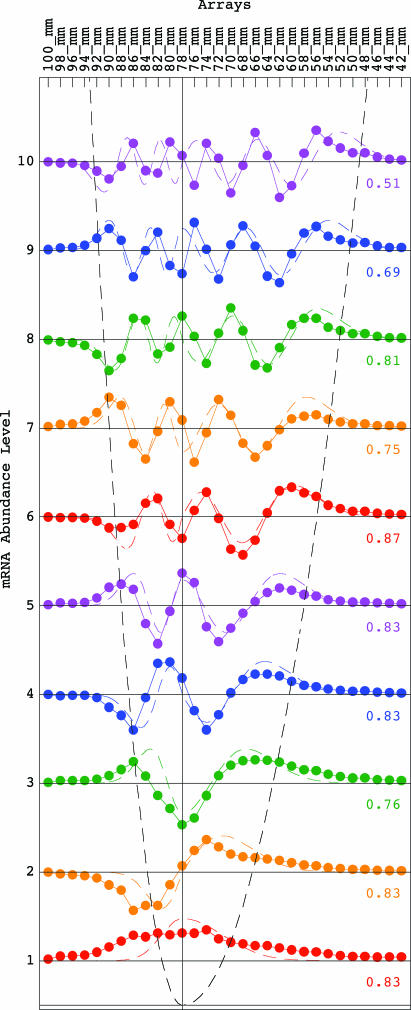

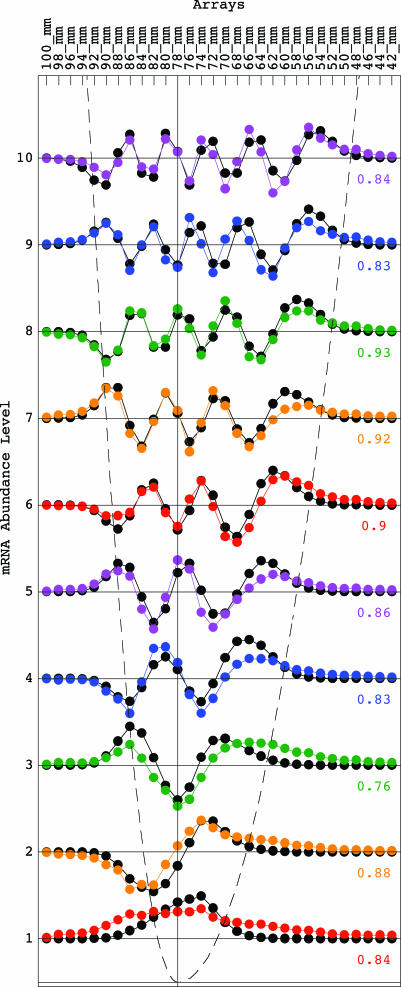

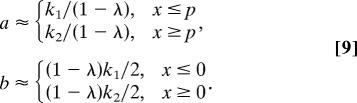

We fit the nth eigengene with the (n − 1)th continuous “asymmetric Hermite function,” where the generalized Hooke’s constant is asymmetric with respect to the equilibrium x = 0 (Fig. 2),

These asymmetric Hermite functions form only an approximately orthogonal basis. The (n − 1)th asymmetric Hermite function is, therefore, normalized after discretization by sampling at unit intervals in the range x ∈ [−11, 18], where the equilibrium x = 0 is set at the gel migration length of 78 mm, and then fit to the nth eigengene, for n = 1, … , 10. We find that the “asymmetric generalized Hooke’s constant” is approximately k = k1 ≈ 0.36 for x ≤ 0 and k = k2 ≈ k1/4 ≈ 0.09 for x ≥ 0. The arithmetic mean of the correlations between the (n − 1)th asymmetric Hermite function and the nth eigengene for n = 1, … , 10 is ≈0.78. The inflection points of the eigengenes approximately sample the corresponding continuous “asymmetric parabolic potential” kx2/2, where k = k1 for x ≤ 0 and k = k2 = k1/4 for x ≥ 0, at unit intervals (Figs. 1a and 2).

Fig. 2.

Line-joined graphs of the abundance levels of the 1st (red) through 10th (violet) eigengenes of the yeast genome-scale mRNA lengths distribution data, {〈n|v̂T} for n = 1, … , 10, approximately fit dashed graphs of the 0th (red) through 9th (violet) asymmetric Hermite functions of Eq. 4 with correlations ranging from 0.51 to 0.87. The inflection points of the eigengenes approximately sample a dashed graph of the asymmetric parabolic potential at unit intervals.

Asymmetric Generalized Coherent State Model of the Genome-Scale mRNA Lengths Distribution

Assume that the profile of mRNA abundance levels measured for the pth gene across the X slices of gel approximately fits a Gaussian of the variable x which peaks at x = p with the variance σx2 = 1/2a > 0, exp[−a(x − p)2]. Assume also that the distribution of the peaks across the P genes fits a Gaussian of the variable p which peaks at the equilibrium p = x = 0 with the variance σp2 = 1/2b > 0, where σp2 ≫ σx2 such that a ≫ b. With these assumptions, the abundance level of the pth gene transcript as measured by the xth array is proportional to the generalized coherent state (19)

The correlation of the mRNA abundance levels measured by the xth and yth arrays across the P genes, in the limit of P → ∞, is then proportional to the generalized coherent state

|

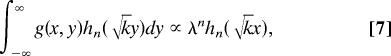

where α = (a2 + 2ab)/[2(a + b)] and β = a2/[2(a + b)]. For a ≫ b, α ≈ a/2 + b and β ≈ a/2. Using Eq. 2, it can be shown that the Hermite functions hn( x) are the eigenfunctions of the integral transform which kernel is g(x, y) in the range x ∈ (−∞, ∞) with the corresponding eigenvalues proportional to the geometric series {λn} (20)

|

where k = 2 and λ = . For a ≫ b, k ≈ 2 and λ ≈ 1 − .

Fractions of Eigen Abundance Fit a Geometric Series.

Fitting the fractions of eigen abundance {Ωn} with the geometric series of Eq. 7 {cλn} for n = 2, … , 10, we find that λ ≈ 0.8. The correlation between the fractions of eigen abundance and the geometric series for n = 2, … , 10 is >0.99 (Fig. 1b). From k = k1 ≈ 0.36 for x ≤ 0, k = k2 ≈ k1/4 ≈ 0.09 for x ≥ 0 and λ ≈ 0.8 for all x, we calculate that a = a1 ≈ 1.6 for x ≤ p, and a = a2 ≈ a1/4 ≈ 0.4 for x ≥ p, and that b = b1 ≈ 0.02 for x ≤ 0, and b = b2 ≈ b1/4 ≈ 0.005 for x ≥ 0. Note that a1/b1 ≈ a2/b2 ≈ 80, such that a ≫ b.

Note also that, for the fractions of eigen abundance computed from the generalized coherent state of Eq. 5 after discretization to fit approximately the geometric series of Eq. 7, it follows that λ ≈ 1 − is symmetric with respect to the equilibrium p = x = 0, whereas for the asymmetric Hermite functions of Eq. 4 to fit approximately the eigengenes computed from the generalized coherent state of Eq. 5 after discretization it follows that k ≈ 2 is asymmetric.

Profiles of mRNA Abundance Levels of Most Genes Fit Asymmetric Gaussians.

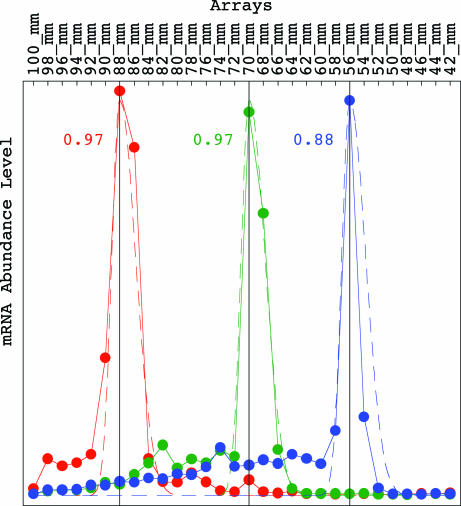

Hurowitz and Brown (11) observed that, for most genes, the profile of mRNA abundance levels of each gene, 〈p|d̂, peaks at only one of the X gel slices. We fit the profiles of mRNA abundance levels measured for the yeast genes VMA7, ADE12 and HIS4, which were selected by Hurowitz and Brown as representative genes, with the asymmetric Gaussians exp[−a(x − p)2], where a = a1 for x ≤ p and a = a2 ≈ a1/4 for x ≥ p, sampled at unit intervals in the ranges x ∈ [−7, 22], [−16, 13], and [−23, 6], such that their peaks are set at the gel migration lengths of 88, 70, and 56 mm, which according to Hurowitz and Brown correspond approximately to the mRNA lengths of 675 ± 35, 1,500 ± 60, and 2,575 ± 100 nucleotides, respectively. We find that the arithmetic mean of the correlations between the measured profile for each of these three genes and the corresponding discretized Gaussian is ≈0.94 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Line-joined graphs of the measured profiles of abundance levels of the yeast genes VMA7 (red), ADE12 (green), and HIS4 (blue) approximately fit dashed graphs of the asymmetric Gaussian exp[−a(x − p)2], where a = a1 for x ≤ p and a = a2 = a1/4 for x ≥ p, and where the Gaussian peak is set at the gel migration lengths of 88, 70, and 56 mm, respectively, with the corresponding correlations of 0.97, 0.97, and 0.88.

Distribution of the Peaks of the Profiles of the Genes Fits an Asymmetric Gaussian.

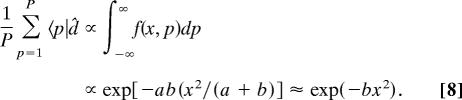

From Eq. 5, the arithmetic mean of the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of the P genes, in the limit of P → ∞, is approximately proportional to the distribution of the peaks x = p across the X gel slices for a ≫ b

|

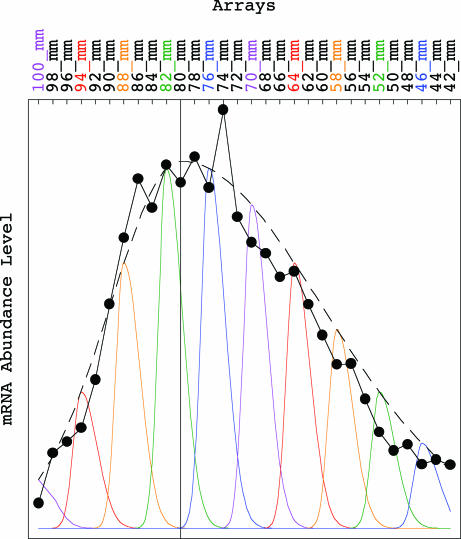

We fit the arithmetic mean of the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of the P genes with the asymmetric Gaussian exp(−bx2), where b = b1 for x ≤ 0 and b = b2 = b1/4 for x ≥ 0, sampled at unit intervals in the range x ∈ [−10, 19], where the equilibrium is set at the gel migration length of 80 mm. We find that the correlation is >0.99 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Asymmetric generalized coherent state model of the yeast genome-scale mRNA lengths distribution data of Eq. 9. Line-joined graph of the arithmetic mean of the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of the P genes of Eq. 8 approximately fits a dashed graph of the asymmetric Gaussian exp(−bp2), which models the distribution of the peaks of the profiles of the genes, where b = b1 for x ≤ 0 and b = b2 = b1/4 for x ≥ 0 and where the Gaussian peak is set at the gel migration length of 80 mm. Graphs of the asymmetric Gaussian exp[−a(x − p)2] model the profiles of the genes, where the Gaussian peaks are set at 100 mm (violet) through 46 mm (blue), and where the Gaussian amplitudes are determined by the distribution of the peaks, which models the relative abundance of each Gaussian peak among all genes.

Genome-Scale mRNA Lengths Distribution Fits an Asymmetric Generalized Coherent State.

We fit the mRNA lengths distribution data with the analytical continuous asymmetric generalized coherent state f(x, p) of Eq. 5, where the variances σx2 = 1/2a and σp2 = 1/2b are asymmetric with respect to the peaks x = p of the profiles of the genes and the equilibrium p = x = 0, respectively (Fig. 4),

|

SVD of the asymmetric generalized coherent state is computed after discretization by sampling at unit intervals in the range x ∈ [−10, 19], where the equilibrium is set at the gel migration length of 80 mm (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We find that the arithmetic mean of the correlations between the nth eigengene computed for the discretized asymmetric generalized coherent state of Eq. 9 and the nth eigengene computed for the measured data for n = 1, … , 10 is ≈0.73. The inflection points of the eigengenes computed for the discretized asymmetric generalized coherent state approximately sample the asymmetric parabolic potential kx2/2, where k = k1 for x ≤ 0 and k = k2 = k1/4 for x ≥ 0 at unit intervals (Figs. 7a and 8, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We find that the correlation between the fractions of eigen abundance computed for the discretized asymmetric generalized coherent state and the geometric series {cλn} for n = 2, … , 10 is >0.99 (Fig. 7b).

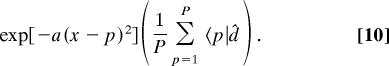

Following Eq. 8, we approximate the distribution of the peaks of the genes exp(−bp2) in the asymmetric coherent state of Eq. 5 with the arithmetic mean of the profiles of the genes

|

SVD is computed again after discretization of exp[−a(x − p)2] by sampling at unit intervals in the range x ∈ [−10, 19], where the equilibrium is set at the gel migration length of 80 mm (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We find that the approximated asymmetric generalized coherent state of Eq. 10 fits the measured data better than the asymmetric generalized coherent state of Eqs. 5 and 9: The arithmetic mean of the correlations between the nth eigengene computed for the approximated and discretized asymmetric generalized coherent state of Eq. 10 and the nth eigengene computed for the measured data for n = 1, … , 10 is ≈0.86 (Figs. 5 and 6). Note also the robustness of the eigengenes and the fractions of eigen abundance computed for the asymmetric generalized coherent state of Eq. 9 to the perturbation introduced by the approximation of Eq. 10.

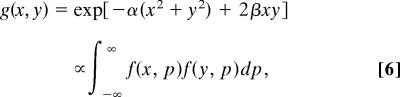

Fig. 5.

Eigengenes of the discretized approximated asymmetric generalized coherent state of Eq. 10. (a) Raster display of the 30 eigengenes in 30 arrays, the inflection points of which approximately sample a graph of the asymmetric parabolic potential (blue) at unit intervals. (b) Bar chart of the 30 fractions of eigen abundance, which approximately fit a graph of the exponential function of n (blue).

Fig. 6.

Line-joined graphs of the abundance levels of the 1st (red) through 10th (violet) eigengenes of the yeast genome-scale mRNA lengths distribution data, {〈n|v̂T} for n = 1, … , 10, approximately fit line-joined graphs of the abundance levels of the 1st through 10th eigengenes (black) of the discretized approximated asymmetric generalized coherent state of Eq. 10 with correlations ranging from 0.76 to 0.93. The inflection points of the eigengenes approximately sample a dashed graph of the asymmetric parabolic potential at unit intervals.

Why Does the Distribution of the Peaks of the Profiles of the Genes Fit an Asymmetric Gaussian?

Our hypothesis is that there are two competing evolutionary forces that determine the lengths of mRNA gene transcripts, and also the distribution of the peaks of the P profiles measured for the P genes. The first force acts to maximize the information content of the genes and their functional specificity, and therefore also their mRNA lengths. The second force acts to minimize the costs associated with the transcription as well as posttranscriptional processes, such as translation, and therefore also the lengths of mRNA gene transcripts. These forces balance at the peak of the distribution exp(−bp2), i.e., the equilibrium p = x = 0. We find the equilibrium at the gel migration length of 80 mm, which according to Hurowitz and Brown (11) corresponds approximately to the mRNA length of 1,000 ± 50 nucleotides. Both forces are linearly proportional to and oppositely directed to the displacement of the gel migration length of a transcript from this equilibrium gel migration length in the manner of the restoring force of the harmonic oscillator. Note that the gel migration length of a transcript is approximately linearly proportional to the logarithm of the mRNA length of the transcript (3, 11). The proportionality constants are b = b1 for the first force in the range of x ≤ 0, and b = b2 for the second force in the range of x ≥ 0. We find that b2 ≈ b1/4, suggesting that the first force, which acts to increase mRNA lengths that are shorter than the equilibrium length of 1,000 nucleotides, is larger than the second force, which acts to decrease mRNA lengths that are longer than the equilibrium length.

Why Do the Profiles of mRNA Abundance Levels of Most Genes Fit Asymmetric Gaussians?

Asymmetry in the gel electrophoresis thermal broadening of a moving, rather than a stationary, band of RNA molecules, along the axis of the electric field, might be underlying this previously unknown asymmetry in the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of the genes. When the electric field is turned off, the thermal broadening of a band of RNA molecules in an agarose gel is symmetric along the axis of the field, such that the distribution of the RNA molecules is a Gaussian profile, exp[−a(x − p)2], which peaks at the position where the RNA molecules were loaded onto the gel, x = p. When the electric field is turned on, the RNA molecules migrate in the gel along the axis of the electric field in addition to their thermal diffusion (3–6). The electrophoretic velocity depends on the lengths of the RNA molecules. Molecules which are of the same lengths will migrate with the same velocity and form a moving band. In the thermal broadening of a moving band of RNA molecules the peak of the band is moving toward the front of the band and away from its back. As a result, the width of the band narrows in the direction of migration, σx,1 = for x ≤ p, and widens in the opposite direction, σx,2 = for x ≥ p, such that σx,2 > σx,1, and the distribution of the RNA molecules is an asymmetric Gaussian profile. We find that σx,2/σx,1 = ≈ 2, and therefore that the peak of each Gaussian profile is approximately shifted by (σx,1 − σx,2)/2 within the band, which width is σx,1 + σx,2. Substituting a1 ≈ 0.16 and a2 ≈ 0.4 and taking into account the 2-mm widths of the gel slices, we find that the width of the Gaussian profile is ≈3 mm, and that the peak of the Gaussian profile is shifted by ≈0.5 mm within the band.

Discussion

We have shown, using SVD, that the genome-scale distribution of yeast mRNA gene transcript lengths measured by DNA microarrays can be modeled mathematically as an asymmetric generalized coherent state, where the profiles of mRNA abundance levels of most genes as well as the distribution of the peaks of these profiles fit asymmetric Gaussians. We have hypothesized that the asymmetric Gaussian distribution of the peaks of the profiles of the genes is due to two competing evolutionary forces, which balance at the peak of this distribution, approximately at the mRNA length of 1,000 ± 50 nucleotides. SVD analyses of DNA microarray measured genome-scale distributions of the lengths of unspliced pre-mRNA, spliced mRNA exons and separately mRNA introns in different organisms (22), as well as different experimentally evolved strains of any one organism (23, 24), may be used to study the evolutionary forces which affect mRNA lengths.

We have shown that the asymmetry in the profiles of the genes might be due to a previously unknown asymmetry in the gel electrophoresis thermal broadening of a moving, rather than a stationary, band of RNA molecules. Previous simulations and measurements of DNA band broadening in gel electrophoresis have shown that the broadening of a moving band can be different from that of a stationary band, but have not suggested asymmetry (4–6). We conclude that the mathematical modeling of DNA microarray data might be used to uncover the physical as well as the biological principles which govern the activities of DNA and RNA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. B. Oberman for recognizing that the eigengenes are Hermite functions, for recognizing that the asymmetric band broadening is due to a shift of the Gaussian peak within the moving band, and for many very insightful discussions. We also thank J. J. Collins, T. A. Duke, A. Goriely, J. Ross, and M. O. Vlad for thoughtful and thorough reviews of this manuscript and M. V. Berry, D. Botstein, P. O. Brown, G. M. Church, E. H. Hurowitz, V. R. Iyer, W. H. Press, G. W. Slater, and D. W. L. Sumners for helpful comments. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant CCR-0430617 (to G.H.G.) and a National Human Genome Research Institute Individual Mentored Research Scientist Development Award in Genomic Research and Analysis (K01 HG00038) (to O.A.).

Abbreviation

- SVD

singular value decomposition.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

In this manuscript, m̂ denotes a matrix, |v〉 denotes a column vector, and 〈u| denotes a row vector, such that m̂|v〉, 〈u|m̂, and 〈u|v〉 all denote inner products and |v〉 〈u| denotes an outer product.

References

- 1.Church G. M., Gilbert W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Southern E. D. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerman L. S., Frisch H. L. Biopolymers. 1982;21:995–997. doi: 10.1002/bip.360210511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duke T. A., Viovy J. L. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992;68:542–545. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slater G. W. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:1–7. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinland B., Pernodet N., Pluen A. Biopolymers. 1998;46:201–214. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(19981005)46:4<201::AID-BIP2>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fodor S. P., Rava R. P., Huang X. C., Pease A. C., Holmes C. P., Adams C. L. Nature. 1993;364:555–556. doi: 10.1038/364555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schena M., Shalon D., Davis R. W., Brown P. O. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown P. O., Botstein D. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:33–37. doi: 10.1038/4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollack J. R., Iyer V. R. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:515–521. doi: 10.1038/ng1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurowitz E. H., Brown P. O. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R2. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golub G. H., Van Loan C. F. Matrix Computation. 3rd Ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alter O., Brown P. O., Botstein D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10101–10106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung M. K., Tegner J., Collins J. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6163–6168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092576199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlad M. O., Arkin A. P., Ross J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7223–7228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402049101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alter O., Golub G. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17559–17564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509033102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiff L. I. Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alter O., Yamamoto Y. Quantum Measurement of a Single System. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glauber R. J. Phys. Rev. 1963;131:2766–2788. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daubechies I. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 1988;34:605–612. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alter O., Golub G. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16577–16582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406767101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yandell M., Mungall C. J., Smith C., Prochnik S., Kaminker J., Hartzell G., Lewis S., Rubin G. M. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006;2:E15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenski R. E., Travisano M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:6808–6814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunham M. J., Badrane H., Ferea T., Adams J., Brown P. O., Rosenzweig F., Botstein D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16144–16149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242624799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.