Abstract

The TandemHear® percutaneous ventricular assist device can be used to support patients in cardiogenic shock (until cardiac recovery occurs or as a bridge to definitive therapy) or as a temporary application during high-risk coronary interventions.

The TandemHeart is a left atrial-to-femoral artery bypass system comprising a transseptal cannula, arterial cannulae, and a centrifugal blood pump. The pump can deliver flow rates up to 4.0 L/min at a maximum speed of 7500 rpm.

From May 2003 through May 2005, the TandemHeart was used to support 18 patients (11 in cardiogenic shock and 7 undergoing high-risk percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty). The patients in cardiogenic shock were supported for a mean of 88.8 ± 74.3 hours (range, 4–264 hr) at a mean pump flow rate of 2.87 ± 0.56 L/min (range, 1.8–3.5 L/min). The mean cardiac index improved from 1.57 ± 0.31 L/min/m2 before support to 2.60 ± 0.34 L/min/m2 during support. The mean duration of support for the high-risk percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty patients was 5.5 ± 8.3 hours (range, 1–24 hr). The mean flow rate was 2.42 ± 0.55 L/min (range, 1.5–3.0 L/min). The overall 30-day survival rate was 61.

In our experience, the TandemHeart device was easy to insert and provided a means either to cardiac recovery or to continued support with an implantable left ventricular assist device.

Key words: Angioplasty, transluminal, percutaneous coronary; blood vessel prosthesis implantation; heart-assist devices; hemodynamic processes; humans; shock, cardiogenic

Implantable mechanical circulatory support (MCS) systems have evolved over the past 25 years and are now in widespread use. The most frequently used of the MCS systems are fully implantable or require direct cannulation of the heart. Because cardiac surgery with the aid of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is usually required for the implantation of most of these devices, their use may be limited in patients with severe heart failure.1–3 One exception is the intraaortic balloon pump (IABP), which can be applied in a variety of hospital environments and used in a wide range of patients. However, the IABP is limited in the amount of cardiac support it provides and in its duration of use. Therefore, a percutaneous MCS system that could be implemented quickly and provide a level of support that would normalize the cardiac index could potentially save more patients with severe heart failure.4

The Tandem Heart® Percutaneous Ventricular Assist Device (pVAD)™ system (Cardiac Assist, Inc.; Pittsburgh, Pa) uses a transseptal cannula that allows direct unloading of the left heart at blood flow rates sufficient to sustain patients.5 The system, which can be inserted in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, can support patients until cardiac recovery occurs or until another treatment approach, such as an implantable MCS system, is chosen.6 In addition, the TandemHeart can be used temporarily during high-risk coronary interventions.5,7 We report our initial experience at the Texas Heart Institute with the TandemHeart pVAD.

Patients and Methods

The TandemHeart is a left atrial-to-femoral artery bypass system that includes a transseptal cannula, arterial cannulae, and a centrifugal blood pump (Fig. 1). A 21F transseptal inflow cannula aspirates oxygenated blood from the left atrium. Blood is then pumped into the femoral artery through the 15F or 17F arterial cannulae. The continuous-flow centrifugal pump can provide flows of 3.5 L/min to 4.0 L/min, at a maximum speed of 7500 rpm. The pump rotates on a lubricating fluid film and is driven by an electromagnetic motor. The continuous infusion of a heparin solution into the lower inner housing of the pump allows lubrication and cooling, which aids in the prevention of thrombosis in the pump chamber. The external microprocessor-based controller provides the electri-cal drive for the pump and the fluid infusion for lubrication and anticoagulation. The controller also monitors system performance and displays impeller speed and pump flow. A secondary blood-flow monitoring system uses an ultrasonic flow probe (Transonic Systems Inc.; Ithaca, NY). Auditory and visual alerts notify the operator of problems with the system, such as low flow rates and power loss.

Fig. 1 The TandemHeart® pVAD™ system includes a left atrial transseptal inflow cannula, arterial return cannula, a centrifugal blood pump, and a system controller.

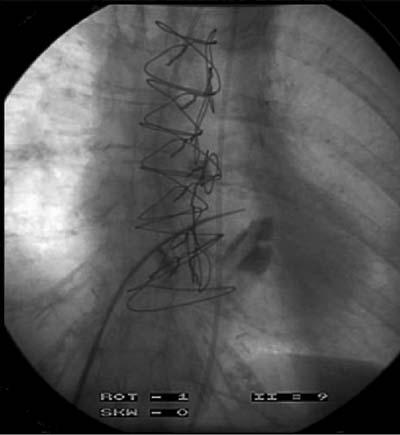

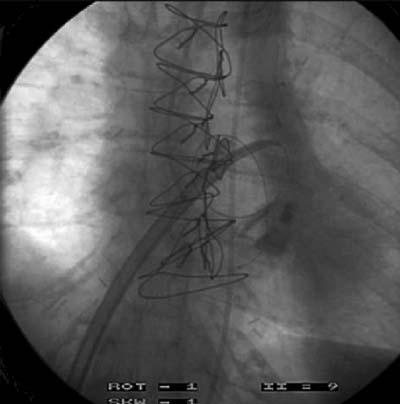

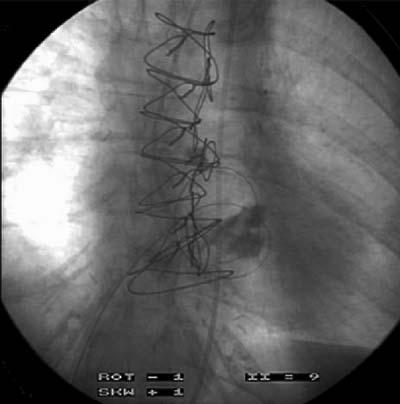

Using fluoroscopic guidance, a transseptal puncture is made between the right and left atria, via the femoral vein (Fig. 2). Iliac angiography before implantation is recommended to confirm that the femoral artery will accommodate the arterial return cannula. A guidewire is inserted into the left atrium, and the interatrial septum is dilated using a 2-stage dilator (14F and 21F) (Figs. 3 and 4). Proper positioning of the cannula is confirmed by fluoroscopy. The guidewire and obturator are removed, and the transseptal cannula tip remains in the left atrium. Initially, intravenous heparin (100 U/kg) is administered to achieve an activated clotting time (ACT) longer than 250 seconds. The ACT is maintained at more than 200 seconds for the remainder of support. The arterial outflow cannula is then inserted into the contralateral femoral artery and advanced until the tip is at the level of the aortic bifurcation. If patients have small femoral arteries or peripheral vascular disease, dual arterial cannulation with smaller cannulae (12F) may be necessary. The cannulae are then connected to the pump, and the system is de-aired. The pump is turned on and the speed increased until the desired flow rate is attained. The cannulae and pump are carefully secured to the patient's thigh, and the patient must remain immobile to ensure that the cannulae do not dislodge or kink. The TandemHeart is explanted by surgical removal of the arterial and transseptal cannulae after they are disconnected from the pump.

Fig. 2 Radiograph of the transseptal puncture from the right atrium to the left atrium.

Fig. 3 The interatrial septum is dilated using a 2-stage dilator (14F and 21F).

Fig. 4 A guidewire is inserted across the interatrial septum.

Results

Eighteen patients (16 men and 2 women; mean age, 61 years) underwent implantation of a TandemHeart from May 2003 through May 2005 (Tables I and II). The duration of support ranged from 1 hour to 11 days (mean, 2.7 days). Indications for use were high-risk percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) (in 7 patients) and cardiogenic shock (in 11 patients). Eleven patients (61%) survived for 30 days or more after TandemHeart support was discontinued.

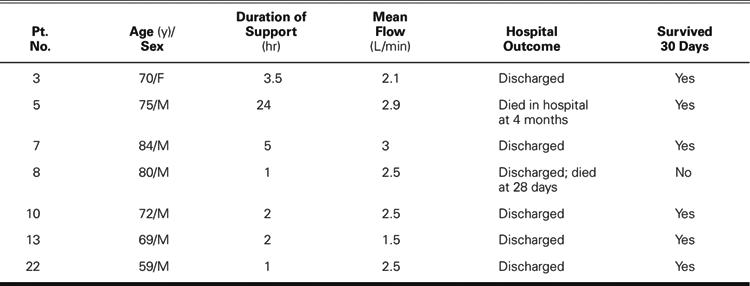

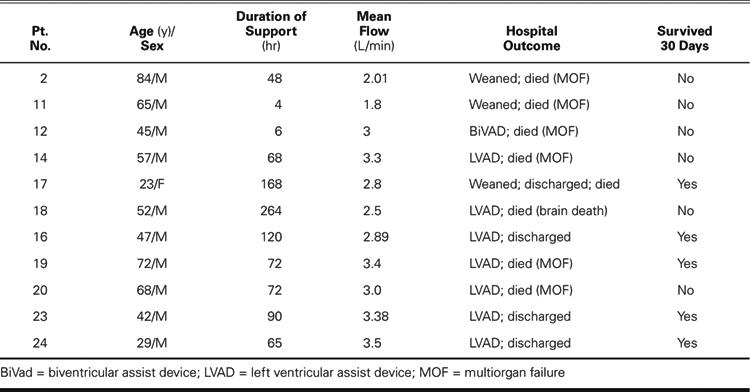

Table I. High-Risk Percutaneous Coronary Angioplasty Patients (n=7)

Table II. Patients in Cardiogenic Shock (n=11)

In the 7 high-risk PTCA patients, death was considered imminent without intervention, but surgery was deemed inadvisable. Successful TandemHeart implantation and angioplasty were performed in all of the PTCA patients. The mean duration of support for the PTCA patients was 5.5 ± 8.3 hours (range, 1–24 hr). The mean pump flow was 2.42 ± 0.55 L/min (range, 1.5–3.0 L/min). Six of the PTCA patients were discharged from the hospital: 5 had successful long-term outcomes, and 1 died 28 days after TandemHeart support was discontinued. One patient was not discharged from the hospital and died of multiorgan failure 4 months after discontinuation of TandemHeart support.

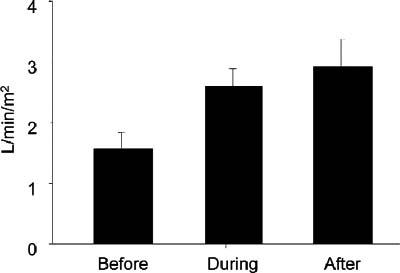

The 11 patients in cardiogenic shock were initially treated with inotropic agents and IABP insertion, but their hemodynamic instability necessitated a higher level of support. The TandemHeart supported these 11 patients for an average of 88.8 ± 74.3 hours (range, 4–264 hr). The mean pump flow was 2.87 ± 0.56 L/min (range, 1.8–3.5 L/min). The mean cardiac index was 1.57 ± 0.31 L/min/m2 before support and improved to 2.60 ± 0.34 L/min/m2 during support (Fig. 5). Although cardiac support with the TandemHeart was adequate, none of the cardiogenic shock patients showed signs of significant recovery of cardiac function. Therefore, 7 of these patients received long-term implantable LVADs, and 1 received a biventricular assist device (BiVAD). In the other 3 patients, LVAD implantation was inadvisable because of multiple comorbidities. The mean cardiac index for these patients after LVAD support (and BiVAD in 1 case) was initiated was 2.93 ± 0.50 L/min/m2. Five of the 11 patients (45%) survived for 30 days or more, and 6 of the patients died within 30 days (5 of multiorgan failure and 1 of anoxic brain death after cardiac arrest).

Fig. 5 For patients who were in cardiogenic shock, the mean cardiac index improved during TandemHeart® pVAD™ support and further increased after implantation of a left ventricular assist device.

Hemolysis was not detected in any of the patients during TandemHeart support. The atrial septostomy was surgically closed in those patients who underwent LVAD implantation. Follow-up echocardiographic studies in the surviving PTCA patients showed no lasting right-to-left atrial shunt.

Discussion

Our experience to date with the TandemHeart system indicates that it is safe and effective. In this series, device-related adverse events were few, and hemodynamics improved in all patients. Infection and thromboembolism did not occur in this series; however, thrombi were noted at the end of the inflow cannula in 3 patients. In all patients, the flow rate was decreased to 2 L/min during weaning from support. The pump flow rate ranged from 1.5 to 3.5 L/min, which resulted in an average cardiac index of 2.62 L/min/m2. This level of support is sufficient to avoid progressive organ failure in most patients. Although 6 patients died of multiorgan failure (4 of whom underwent LVAD implantation), other severe comorbidities led to their deaths despite an adequate cardiac index. The rapid application of TandemHeart support appears to be critical in avoiding other organ dysfunction.

For 30 years, the IABP has been used extensively to support patients with acute heart failure in a variety of clinical scenarios. The major advantage of the IABP is its ease of implementation; however, the pump flow rates are limited to approximately 1.5 L/min. TandemHeart placement is somewhat more challenging because of the need for transseptal cannulation and fluoroscopic or echocardiographic guidance, but the system can provide up to 4 L/min of support and is implanted without anesthesia or surgery. The Tandem Heart usually can be inserted in less than 1 hour, but lack of rapid access to a catheterization laboratory and the required specially trained staff can make the insertion times longer than those of the IABP. The higher level of support provided by the TandemHeart results in better hemodynamics and metabolic parameters, although it may not improve the survival rate.4

We have found that a properly trained team can easily implant the TandemHeart system in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. The cannulation, pump assembly, and system operation are not complex, and we have encountered few technical difficulties (average insertion time, 45–60 min). Although transseptal cannulation is technically challenging, it was accomplished in all patients except 1, whose severe peripheral vascular disease prevented vascular access.

In our series, the 100% success rate for implementing TandemHeart support during high-risk PTCA is encouraging. There were no serious adverse events, and the hospital discharge rate indicates a positive risk–benefit ratio. The 2 late deaths that occurred in our series were not related to TandemHeart support or PTCA. However, patients in cardiogenic shock after myocardial infarction who require PTCA or CABG may present a greater challenge. Thiele and colleagues4 compared IABP and TandemHeart support in patients who were in cardiogenic shock and found that the TandemHeart patients benefited from the higher level of support; nevertheless, mortality in that small series was not greatly affected.

In our series, the acceptable risk–benefit ratio for high-risk PTCA and cardiogenic shock patients was positive. Further studies are needed to better define the indications for TandemHeart use and to further refine supportive care. As experience is gained, it may be possible shorten the interval between cardiogenic shock and TandemHeart support.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Reynolds M. Delgado III, MD, 6624 Fannin St., Suite 2180, Houston, TX 77030. E-mail: delgado.reynolds@sbcglobal.net

References

- 1.Oz MC, Gelijns AC, Miller L, Wang C, Nickens P, Arons R, et al. Left ventricular assist devices as permanent heart failure therapy: the price of progress. Ann Surg 2003;238:577–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Heitjan DF, Stevenson LW, Dembitsky W, et al. Long term mechanical left ventricular assistance for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1435–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Myers TJ, Kahn T, Frazier OH. Infectious complications with ventricular assist systems. ASAIO J 2000;46:S28-S36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Thiele H, Sick P, Boudriot E, Diederich KW, Hambrecht R, Niebauer J, et al. Randomized comparison of intra-aortic balloon support with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with revascularized acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J 2005; 26:1276–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Kar B, Butkevich A, Civitello AB, Nawar MA, Walton B, Messner GN, et al. Hemodynamic support with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device during stenting of an unprotected left main coronary artery. Tex Heart Inst J 2004; 31:84–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Pitsis AA, Dardas P, Mezilis N, Nikoloudakis N, Filippatos G, Burkhoff D. Temporary assist device for postcardiotomy cardiac failure. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77:1431–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Aragon J, Lee MS, Kar S, Makkar RR. Percutaneous left ventricular assist device: “TandemHeart” for high-risk coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005;65:346–52. [DOI] [PubMed]