Abstract

Early mobilization and aggressive physical therapy are essential in patients who receive left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) due to long-term, end-stage heart failure. Some of these patients remain ventilator dependent for quite some time after device implantation. We report our regimen of mobilization with the aid of a portable ventilator, in patients with cardiac cachexia and LVAD implantation. Further, we describe the specific physical therapy interventions used in an LVAD patient who required prolonged mechanical ventilation after device implantation. The patient was critically ill for 5 weeks before the surgery and was ventilator dependent for 48 days postoperatively. There were significant functional gains during the period of prolonged mechanical ventilation. The patient was able to walk up to 600 feet by the time he was weaned from the ventilator and transferred out of the intensive care unit. He underwent successful heart transplantation 6 weeks after being weaned from the ventilator. We believe that improving the mobility of LVAD patients who require mechanical ventilation has the potential both to facilitate ventilator weaning and to improve the outcomes of transplantation.

Key words: Activities of daily living; critical care; early ambulation; exercise therapy; heart failure, congestive/rehabilitation; heart transplantation; heart-assist devices; physical therapy modalities/methods; postoperative care; ventilators, mechanical; ventilator weaning; ventricular dysfunction, left/surgery

Severe heart failure is associated with limited tolerance of activity, cachexia, and loss of muscle mass. Some patients develop progressive end-stage heart failure and become severely symptomatic at rest or with minimal exertion, despite maximal medical therapy. At this point, the treatment options include cardiac transplantation or placement of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Left ventricular assist devices have been developed to provide circulatory support, reestablish adequate cardiac output, and help recovery from secondary organ dysfunction. The Food and Drug Administration has recently approved the use of LVADs as destination therapy for patients with end-stage heart failure who are not eligible for heart transplantation. These devices are also approved for postcardiotomy heart failure, acute cardiogenic shock, and serving as a bridge to heart transplantation.1 Recently, the REMATCH* trial has shown that LVAD therapy for selected patients with terminal heart failure is superior to medical therapy in alleviating symptoms and improving outcomes, including survival rates and quality of life.2

Patients who require mechanical circulatory support are severely deconditioned and may require prolonged mechanical ventilation consequent to postoperative respiratory failure. Their mobility becomes very limited due to multiple medical problems, life-support or monitoring equipment, and weakness. The period of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) often entails prolonged bed rest and can be devastating, leading to significant loss of functional ability. Patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation are prone to high morbidity rates, high costs of care, and poor functional outcomes. Before returning home, these patients often spend extended periods of time in acute care or rehabilitation units. They are challenged to regain their ability to walk and their independence. We present this case to illustrate that a physical therapy program initiated in the ICU and focused on early mobilization and ambulation can improve functional mobility. In addition, such therapy has the potential to assist with ventilator weaning, as overall strength and endurance improve. When recipients of left ventricular assist devices require prolonged mechanical ventilation, their prospects of successful transplantation are improved by physical therapy in the ICU—with a focus on early mobilization and ambulation.

Physical Therapy Intervention

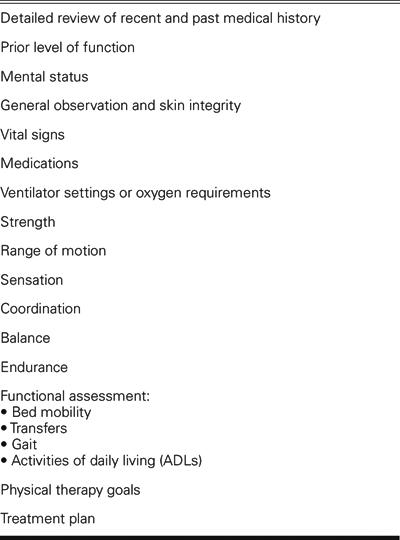

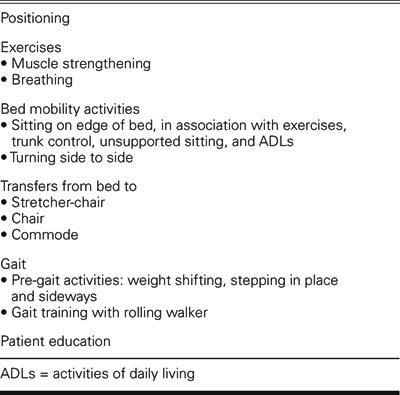

In the cardiovascular ICU at The Methodist DeBakey Heart Center, Houston, patients who receive an LVAD are usually referred to physical therapy within 48 hours after surgery. At this time, the patient is evaluated by a physical therapist, the physical therapy goals are set, and an individualized treatment plan is outlined (Table I). The initial physical therapy goals are to prevent postoperative complications of bed rest.3 Physical therapy interventions are dependent on overall medical condition and hemodynamic stability (Table II). The ultimate goals of physical therapy for LVAD patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation are to minimize loss of mobility, maximize independence, and facilitate weaning.

Table I. Physical Therapy Evaluation

TABLE II. Physical Therapy Interventions

For the patient with complex medical problems or neurologic deficits postoperatively, the physical therapy goals and treatment are modified. Some conditions may significantly limit the patient's functional mobility. These conditions include, but are not limited to

Altered mental status with inability to follow commands and minimal ability to participate in planned activities.

Cerebral vascular accident with significant loss of muscle function and inability to bear weight.

Cardiovascular instability on high-dose or multiple inotropic drugs.

Significant impairment of oxygenation that requires high oxygen concentration, paralytic drugs, or sedation.

In these situations, the physical therapist continues to work with other health professionals to help the patient achieve the highest level of function possible within his or her medical limitations. As the medical condition improves and the patient is able to participate in planned activities, the physical therapy program is advanced to focus on early mobilization and ambulation, as tolerated.

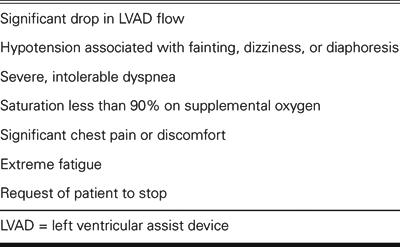

Appropriate ventilator support and supplemental oxygen are imperative to enable the patient to tolerate increased levels of exertion. It is important for the physical therapist to communicate closely with physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists to ensure safe mobilization of such complex patients. Once the mechanically ventilated patient is able to walk a few steps with the aid of a walker and assistance, a portable ventilator is very useful to enable greater distance. The patient is closely monitored for any signs of activity intolerance throughout physical therapy sessions, and treatment is terminated when the patient reaches his or her limit (Table III). The frequency of physical therapy is once a day for 6 to 7 days per week. Its duration can vary from 15 minutes to 1 hour, as tolerated.

Table III. Criteria for Termination of Physical Therapy Session

Case Report

In February 2003, a 51-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy (New York Heart Association functional class IV) and a right lower lobe nodule. During the 5 weeks after hospital admission, the patient's condition progressively worsened despite optimal inotropic and intra-aortic balloon pump support. He developed renal insufficiency and respiratory failure that required mechanical ventilation. During this period, the patient was on bed rest and dependent upon help with all activities of daily living, due to the severity of his heart failure. The patient underwent insertion of a ventricular assist device (MicroMed DeBakey VAD®; MicroMed Cardiovascular, Inc.; Houston, Tex) and right lower lobe wedge resection of a pulmonary granuloma. The postoperative period was complicated by multiple medical problems, which included respiratory failure that led to prolonged mechanical ventilation. The patient was referred to physical therapy on postoperative day 7, after the 1st ventilator weaning trial failed.

Following a complete physical therapy evaluation, treatments were initiated. These included lower-extremity-strengthening exercises and mobilization: sitting on the edge of the bed, standing at the bedside, and moving from the bed to a chair. Once the patient was able to stand safely with a walker and assistance, gait-training activities were initiated around the bed and progressed to the hallway in the ICU. The patient was mobilized and started walking while still on the ventilator. Aggressive early physical therapy was provided in order to enhance the overall recovery of this multimorbid patient.

Results

Postoperatively, the patient stayed in the ICU for 49 days and was ventilator dependent for 48 days. The patient received 25 daily physical therapy sessions. The physical therapy interventions in this patient included

Lower-extremity exercises: 17 sessions

Sitting on edge of bed: 22 sessions

Standing: 21 sessions

Gait training with walker: 18 sessions

A portable ventilator was used in 4 gait-training sessions, and it enabled a significant increase in distance walked, as well as improvement in activity tolerance (Fig. 1). After this, the patient was able to start trials of spontaneous breathing while off the ventilator, with supplemental oxygen provided by a tracheostomy collar (T-collar). He subsequently tolerated ambulation without ventilatory support, and progressed rapidly with the ventilator-weaning process. It is important to consider that this patient was critically ill during the 5 weeks preceding LVAD implantation. Despite this, the patient showed substantial functional gains during the period of prolonged mechanical ventilation and bed rest after LVAD implantation. Upon transfer from the ICU, the patient required minimal assistance for out-of-bed activities and was able to walk 600 feet with the aid of a rolling walker and supervision (Fig. 2). After 6 weeks in acute care, the patient underwent successful heart transplantation. The patient was discharged from the hospital but has had recurrent respiratory problems that have led to hospital readmissions.

Fig. 1 A portable ventilator, used in the intensive care unit, enabled a significant increase in distance walked and activity tolerance.

Fig. 2 Before transfer to a nursing floor, the patient was weaned from the ventilator and was able to walk 600 feet with the aid of a rolling walker and supervision.

Discussion

Insertion of an LVAD can significantly improve exercise performance and quality of life in patients with end-stage heart failure. Physical therapists working in the ICU face complex challenges when treating LVAD patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation. The implementation of an early physical therapy program with focus on early mobilization and ambulation, in our experience and opinion, is essential to minimize functional decline. In our institution, this therapy is well accepted by patients, physicians, nurses, therapists, and family members. It appears to improve functional outcomes by optimizing cardiopulmonary and neuromuscular status, as well as by maximizing independence. We also believe that, in this patient, the improvement in overall strength and endurance may have facilitated weaning from mechanical ventilation. To our knowledge, no one has examined the effect of early mobilization and ambulation on patients who need mechanical ventilation. According to a report4 that reviewed the literature, the ability of physical therapy to facilitate ventilator weaning is unknown. In our experience, early mobilization and ambulation of patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation contributes to higher functional capability and an improvement in patients' quality of life. It is important to note that our patient's medical condition never deteriorated as a direct result of the physical therapy interventions. We believe that early physical therapy can significantly improve the outcomes of subsequent transplantation for selected mechanically ventilated LVAD patients.

Footnotes

*Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart Failure

Address for reprints: Christiane Perme, PT, CCS, 6565 Fannin St., M1-024, Houston, TX 77030. E-mail: cperme@tmh.tmc.edu

References

- 1.Radovancevic B, Vrtovec B, Frazier OH. Left ventricular assist devices: an alternative to medical therapy for end-stage heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol 2003;18:210–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Rose EA, Gelijns AC, Moskowitz AJ, Heitjan DF, Stevenson LW, Dembitsky W, et al. Long-term mechanical left ventricular assistance for end-stage heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1435–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Morrone TM, Buck LA, Catanese KA, Goldsmith RL, Cahalin LP, Oz MC, Levin HR. Early progressive mobilization of patients with left ventricular assist devices is safe and optimizes recovery before heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 1996;15:423–9. [PubMed]

- 4.Stiller K. Physiotherapy in intensive care: towards an evidence-based practice. Chest 2000;118:1801–13. [DOI] [PubMed]