Abstract

A 7-week-old piglet was presented with a 2-hour history of neurological signs progressing to death. Necropsy, bacteriologic culture, and immunohistochemical staining indicated an unusual case of Streptococcus suis-like bacterial meningitis and S. suis type 3 septicemia. Management and control of this important bacterial disease are discussed.

Résumé

Méningite et septicémie causées par une co-infection streptococcique chez un porcelet de 7 semaines. Un porcelet de 7 semaines est présenté avec des antécédents de 2 heures de signes neurologiques progressant jusqu’à la mort. Une autopsie, une culture bactériologique et une coloration immunohistochimique ont indiqué un cas inhabituel de méningite bactérienne s’apparentant à Streptococcus suis et de septicémie S. suis de type 3. La gestion et le contrôle de cette importante maladie bactérienne sont discutés.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

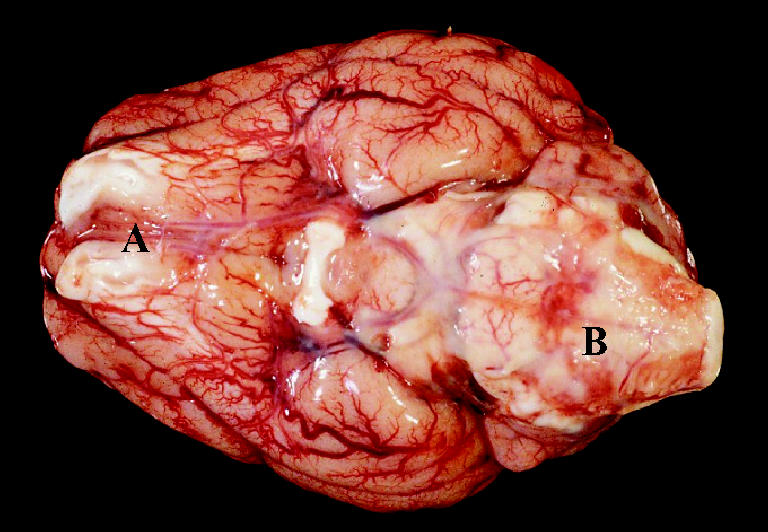

A 7-week-old barrow piglet was presented on a herd health visit to a 1300 head farrow to finish swine unit in September 2004. It had a 2-hour history of ataxia that quickly progressed to convulsions and death. On post mortem examination at Prairie Diagnostic Services (PDS, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan), multiple lesions were found. There was an 8-cm soft swelling on the left front leg, proximal and lateral to the elbow, which was filled with serosanguinous gelatinous fluid and fibrin. Multiple lymph nodes were diffusely enlarged, wet, and reddened. Bilaterally, the stifles, elbows, and hock joints were slightly wet. The peritoneum contained a small amount of fibrin. The spleen had peripheral multifocal 2-cm dark purple lesions. The epicardial vessels were mildly injected. The meninges were diffusely injected and the cerebral sulci were grey. Dorsocaudally on the cerebellum, there was alocally extensive area of opacity in the meninges. Ventrally, the brain stem was congested and the meninges were mildly opaque (Figure 1). An impression smear of the cerebellar plaque showed many nondegenerate neutrophils and red blood cells, as well as some lymphocytes and macrophages. Multiple tissues were submitted for histopathologic examination, bacteriologic culture, and immunohistochemical staining.

Figure 1.

A ventral view of the brain of the necropsied 7-week-old piglet (approximately 10 cm in length). The meninges are injected and opaque, particularly on the ventral surface of the brain stem (B). A: Olfactory bulbs.

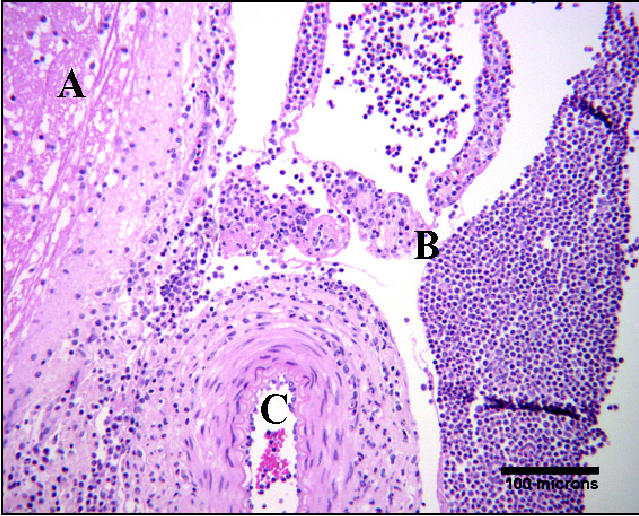

On histopathologic examination, many tissues were abnormal. There was a moderate rhinitis without evidence of viral inclusion bodies. Lymphatic tissues (tonsil and lymph nodes) were reactive and congested. There was generalized venous congestion in the liver and kidney due to septicemia; the liver also had mild peripheral parenchymal atrophy. There were multifocal venous infarcts in the spleen, also due to septicemia. The lung tissue was atelectatic and some vessels had mild perivascular cuffing. A mild, suppurative locally extensive arthritis was seen in the left hock joint. The fluid filled bursa was due to suppurative chronic cellulitis. In the brain, there was severe meningitis, characterized by a suppurative subarachnoid infiltrate. There was also meningial edema and blood vessels containing many neutrophils; this was most evident on the ventrum of the brain stem (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the meninges on the ventral surface of the brain stem, 100 × objective. A: Ventral brain stem. B: Subarachnoid space filled with inflammatory cells, predominantly neutrophils. C: Artery containing neutrophils.

Bacteriologic culture yielded multiple pathogens. The most significant were Streptococcus suis type 3 cultured from the spleen and bursa, and a pure culture of S. suis-like organisms obtained from the cerebrospinal fluid. This organism was classified as such because of minor differences in biochemical tests from those used as the identification scheme for S. suis by PDS. The bursa also contained Escherichia coli (non-hemolytic) and Neisseria spp. Escherichia coli (non-hemolytic) was also cultured from the spleen.

Immunohistochemical staining using Streptococcus suis type 3 antiserum was positive in the brain and bursa, and strongly positive in the tonsil. Immunohistochemical staining was also done with Porcine circovirus Type 2 antiserum; this was negative in liver, spleen, and tonsil. A Gram stain was performed; several areas of the brain contained stain that was strongly suspicious of gram-positive cocci. The tonsilar crypts contained many gram-positive cocci.

The herd of origin of this piglet had been suffering from increased nursery mortality for the previous 2.5 y. A typical case had particularly severe acute meningitis, characterized by ataxia that quickly progressed to convulsions and death. Mortality of this nature usually occurred 2 to 3 wk post weaning (5 to 6 wk of age). The increased mortality began with the introduction of breeding stock from a multiplier unit of this operation in late February 2002. Mortality in the nursery unit from startup (October 1998) until the introduction of the breeding stock had remained between 0.7% and 1.7%. The proportion of deaths attributed to S. suis remained less than 20% from October 1998 to October 2000. In the 6 mo following the new breeding stock additions, nursery mortality increased to 3.6%, and the S. suis proportional death loss rose to 43.0%. Since February 2002, monthly mortality has been as high as 5.2%, and proportion of deaths attributable to S. suis has been 35% to 48%. In September 2004, when the situation was presented, the mortality was 2.6% and S. suis proportional death loss was 32.8% over the previous 3 mo.

In the nursery, there had been a chronic problem of piglets sneezing, which occurred for approximately 1 wk at 5 to 6 wk of age. There had been no evidence of atrophic rhinitis and little mortality due to pneumonia (3.6% of total nursery deaths from October 2003 to September 2004). This may have been due to noxious gases, dust, or infectious disease. Streptococcal disease may have been enhanced in this herd by sneezing. Inflammation of surface epithelium provides a potential portal of entry for disease-causing organisms, such as S. suis. The etiology of the sneezing may also be associated with an increased pathogen load, as high levels of dust cause sneezing by irritation and also transmit a greater pathogen load.

Periodic laboratory submissions of pigs succumbing to meningitis had demonstrated cultures of various Streptococcus spp. from meninges and septicemic lesions. In December 2003, S. suis was cultured at PDS from a brain swab of a 5-week-old pig; it did not belong to types 1 to 9. This isolate was sensitive only to ceftiofur, and it was intermediately sensitive to ampicillin. In early March of 2004, tissues and swabs were submitted to another laboratory (Gallant Custom Laboratories, Cambridge, Ontario). A Streptococcus sp. similar to S. dysgalactiae was cultured from 3 brain swabs, S. suis type 2 was cultured from another brain swab, and S. suis not belonging to types 1 to 9 was cultured from a spleen. These cultures were all sensitive only to ampicillin and amoxicillin, and intermediately sensitive to ceftiofur. In late March of 2004, additional samples were submitted to PDS: S. suis-like bacteria were cultured from a brain swab; these were later identified as S. suis type 7.

Historically, newly weaned piglets at this unit were given medicated water 3 d after entering the nursery. Penicillin G potassium (Penicillin G potassium USP soluble powder; Bio Agri Mix 1998, Mitchell, Ontario) was mixed at a rate of 60 g in 4 L of water, and added to the water supply with a medicator set to 1:128 dilution. The dosing scheme assumed an intake of water of 7% to 10% of BW/head/d. This drug was given orally for 3 d, removed for 3 d, then given for an additional 3 d.

Several aspects of the management of this operation were altered during the previous 2.5 y to improve piglet health and reduce mortality. The dose of penicillin G potassium was increased to 100 g in 4 L of water in times of increased morbidity. In December of 2002, amoxicillin trihydrate 100% soluble powder was prescribed to be mixed at a rate of 60 g in 4 L of water and added to the water supply with a medicator set to 1:128 dilution. This drug was used for 3 d in the water at 3 wk post weaning, and repeated once if needed. At this point, the nursery mortality was 5.0%; this number fell to 3.4% over the next 3 mo. For the next year, mortality remained at 3.0% to 3.8%; the proportional death loss due to S. suis was 40.8% to 49.8%. The parenteral treatment regime for pigs with meningitis (head tilts, convulsions) was ampicillin (Polyflex, ampicillin trihydrate 100 mg/mL; Wyeth Animal Health, Guelph, Ontario), 1 mL/17 kg BW, IM, q24h for 3 d, and dexamethasone (Dexamethasone 5, dexamethasone sodium phosphate 5 mg/mL; Vétoquinol N.A. Lavaltrie, Québec), 1 mL/10 kg BW, IM, q24h for 3 d.

In March 2004, following the multiple diagnoses of bacterial meningitis due to several Streptococcus spp. and continuously high nursery mortality, an autogenous vaccine was developed by Gallant Custom Laboratories Inc. by using previously isolated S. suis type 2; S. suis type 7; S. suis untypeable; and S. dysgalactiae. This vaccine was used on a trial basis from April to June 2004; it was discontinued due to the high cost of production and administration. It was administered to piglets at a dose of 2 mL, IM, 1 wk prior to weaning, and repeated 2 wk later. For the 3 mo prior to the use of the vaccine, the average nursery mortality was 3.5%. During the time the vaccine was used, it was successful in reducing the mortality to 2.6%. The mortality remained at 2.6% for the 3 mo after the vaccine was discontinued.

Streptococcus suis is an economically important pathogen in modern swine operations. It causes several systemic disease states, including meningitis, arthritis, endocarditis, pneumonia, and septicemia. Thirty-five capsular serotypes had been described until 1995 (1); however, there are many strains that are untypeable (2). Diagnosis is based mainly on clinical signs and lesions, but it must be confirmed with bacteriologic culture (1). Many herds, and rarely individual pigs, are infected with more than one strain at a time (3), as in this case. The cause of death in the described pig was meningitis. The severe inflammation resulted in edema, causing increased intracranial pressure and neuronal death. Streptococcus suis type 3 septicemia likely occurred concurrently and contributed to the acuteness of death. The source of infection in this pig was probably its tonsils, as is theorized for most S. suis infections. Streptococcus suis colonizes the tonsils of piglets at the time of farrowing; not all strains are virulent and not all pigs carrying virulent strains become diseased. These “carrier pigs” are likely the source for other pigs (1). Streptococcal disease does not usually appear clinically until after weaning, possibly because of waning maternal antibody and stress induced immunocompromise (2).

The diagnosis of meningitis and septicemia caused by 2 organisms is significant. That the meningeal bacterium could not be definitively identified as S. suis in this case is not of great consequence. If the biochemical definition of S. suis described by Tarradas et al (4) is used, the bacterium is classified as S. suis. In addition, the bacterial culture from late March 2004 identifying a S. suis-like bacterium was later reclassified as S. suis type 7 after further investigation. There is such a large variation in strains of S. suis that diagnosis and identification of the most significant strains must be made based on clinical signs, pathologic studies, and bacteriologic culture. It is recommended that many biochemical tests be used to identify S. suis (5).

The pathogenesis of tonsilar colonization and invasion into the blood is poorly understood. Attempts at experimental infection do not always succeed in producing disease, particularily when an intranasal infection protocol is used (6). Therefore, there must be a critical step, such as immunocompromise or mucosal damage, involved in invasion of the blood. An improved success rate of producing disease was reported when the nasal mucosa was pretreated with intranasal acetic acid, indicating that damage to nasal mucosa promotes invasion (7). Whatever is causing the sneezing in this unit, it may be damaging the mucosa and promoting invasion. Streptococcus suis epidemics have been associated with situations that cause stress, such as overcrowding, temperature fluctuations, increased humidity (8), introduction of new animals, changes in staff, and improper nutrition (9). Stress should be avoided as much as possible, as most pigs harbor this bacterium and some strains will be pathogenic.

Control of this disease relies heavily on prevention and decreasing stress. Since it is an early colonizer, S. suis cannot be eradicated by using conventional segregated early weaning methods. Staff should be well trained to identify sick pigs, so that treatment can take place as early as possible. Vaccination is a rarely used tool: there is no cross protection between strains (3) and autogenous vaccine production is expensive. Fangman and Fales (9) found that an autogenous vaccine, along with other management changes, dramatically decreased clinical signs of S. suis for 1 y. Oral and parenteral medication is a common method of treatment and control (3). An autogenous vaccine did appear to aid in control in this case, but the cost was prohibitive.

Streptococcus suis is an important pathogen to the swine industry, because it can cause high morbidity and mortality, and it is present in most herds. A dual infection with more than one type of S. suis (or S. suis-like bacterium in this case) is not unheard of, but is certainly uncommon. Control should be based on preventing occurrence of the disease, and then identifying and treating it rapidly with management changes and medication, if it becomes apparent clinically.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Drs. M. Jacobson and D. Middleton for their assistance with this case, and Dr. J. Harding for his guidance and advice. CVJ

Footnotes

Dr. Johannson’s current address is Prairie Animal Health Centre of Estevan, P.O. Box 1010, Estevan, Saskatchewan S4A 2H7.

Dr. Johannson will receive 50 free reprints of her article, courtesy of The Canadian Veterinary Journal.

References

- 1.Gottschalk M, Segura M. The pathogenesis of the meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis: the unresolved questions. Vet Microbiol. 2000;76:259–272. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacInnes JI, Desrosiers R. Agents of the “suis-ide diseases” of swine: Actinobacillus suis, Haemophilus parasuis, and Streptococcus suis. Can J Vet Res. 1999;63:83–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amass S, Stevenson G, Knox K, Reed A. Efficacy of an autogenous vaccine for preventing streptococcosis in piglets. Vet Med. 1999;94:480–484. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarradas C, Arenas A, Maldonado A, Luque I, Miranda A, Perea A. Identification of Streptococcus suis isolated from swine: proposal for biochemical parameters. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:578–580. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.578-580.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devriese LA, Ceyssens K, Hommez J, Kilpper-Balz R, Schleifer KH. Characteristics of different Streptococcus suis ecovars and description of a simplified identification method. Vet Microbiol. 1991;26:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90050-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanter N, Jones PW, Alexander TJL. Meningitis in pigs caused by Streptococcus suis — a speculative review. Vet Microbiol. 1993;36:39–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90127-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pallares FJ, Halbur PG, Schmitt CS, et al. Comparison of experimental models for Streptococcus suis infection of conventional pigs. Can J Vet Res. 2003;67:225–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewey CE. Diseases of the nervous and locomotor systems. In: Straw BE, ed. Diseases of Swine. 8th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Univ Pr, 1999:861–882.

- 9.Fangman TJ, Fales WH. Multiple Streptococcus species implicated in lameness and central nervous system signs in piglets and sows. Swine Health Prod. 1999;7:113–115. [Google Scholar]