Abstract

Rhodococcus equi and species of Nocardia and Gordonia may be human opportunistic pathogens. We find that these, as well as several isolates from closely related genera, are highly susceptible to the imidazoles bifonazole, clotrimazole, econazole, and miconazole, whose MICs are ≤1 μg/ml. In liquid cultures 1 μg of the drug/ml was bacteriostatic and 10 μg/ml was bactericidal. On solid media at 10 μg of azole/ml no resistant mutants could be isolated. An MIC of 1 to 15 μg/ml was observed with ketoconazole, whereas none of these organisms was inhibited by the triazoles fluconazole and voriconazole (100 μg/ml). Imidazoles may offer the prospect of treatment of nocardioform mycetomas and may provide the basis for the development of additional antimicrobial agents to combat these pathogens.

There has been an increase in the number of individuals infected with opportunistic pathogens of the nocardioform group of bacteria as a result of the susceptibility of AIDS patients and some other categories of immunocompromised patients (1, 4, 9). The soilborne organism Rhodococcus equi may cause chronic and severe pyogranulomatous pneumonia in foals, and similar symptoms can arise in humans with weakened immune systems; subsequent dissemination from the lung to other body sites sometimes also occurs in either horses or humans (10). Nocardia brasiliensis is a common cause of localized chronic mycetoma in Africa and other tropical areas and may develop into a disseminated infection in immunocompromised individuals (16, 20, 21). Nocardia otitidiscaviarum (3), Dietzia maris (2, 17), Gordonia bronchialis, Gordonia rubripertincta (18), and Mycobacterium vaccae (8) may also infect humans. Increasing incidence of drug resistance and multiple resistance for all main classes of antibiotics in both R. equi (11, 15) and N. brasiliensis (25) makes it desirable to identify additional antibacterial agents, preferably targeting novel elements in the prokaryotic cell to minimize the likelihood of cross-resistance from familiar antibiotics. Antifungal azoles act on organisms such as Candida albicans by blocking a step in the synthesis of ergosterol, resulting in damage to membrane integrity. They are selective inhibitors of the cytochrome P450-dependent 14-α demethylation of lanosterol but have very little effect on mammalian cytochrome P450 (26). The specificity of their mode of action suggests that susceptibility in bacteria is unlikely; however, they inhibit Helicobacter pylori at a concentration of 2 to 64 μg/ml (24). In earlier work miconazole and ketoconazole were shown to inhibit Staphylococcus aureus (22). Metronidazole and other nitroimidazoles are bactericidal against H. pylori through toxic metabolites that cause DNA strand breakage (14). Recently miconazole and clotrimazole have been shown to have in vitro activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the MIC being 2 to 5 μg/ml (23). Here we show that nocardioform opportunistic pathogens and other related strains from seven genera are highly susceptible to bifonazole and econazole as well as to miconazole and clotrimazole. However, fluconazole and the newly developed voriconazole (19) showed no inhibitory effects on any of these organisms.

Strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Cultures were grown on brain heart infusion (BHI; pH 7.4), Luria-Bertani (pH 7.0), or Sabouraud dextrose (SD; 4%, pH 5.6) media solidified where required with 1.5% agar. The nonionic detergent Tween 80 was added to a final concentration of 0.7% to reduce aggregation during optical density (OD) and CFU measurements of cultures. All incubations were at 30°C. Bifonazole, clotrimazole, econazole, and miconazole were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Fluconazole and voriconazole were kindly provided by Pfizer Inc. Solid medium MICs were measured by replicating ∼104 CFU onto plates supplemented with 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10, 20, 50, or 100 μg of drug/ml, followed by further intermediate concentrations where necessary. MICs in liquid BHI medium (10 ml, with five 5-mm glass beads to promote dispersal) were measured by monitoring the effect of drug challenge on viable counts and on OD at 600 nm with a Milton Roy Spectronic 601 spectrophotometer.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of bacterial strains to antifungal drugsa

| Organism | Strain | MIC (μg/ml) on BHI agar

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifonazole | Clotrimazole | Econazole | Ketoconazole | Voriconazole | ||

| Dietzia maris | JCM 6166 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | >100 |

| Gordonia bronchialis | UNT N-654 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | >100 |

| Gordonia rubripertincta | ATCC 25593 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 10 | >100 |

| Mycobacterium parafortuitum | IFM 0490 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 | >100 |

| Mycobacterium vaccae | IFM 0489 | 2.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 8 | >100 |

| Nocardia brasiliensis | IFM 0236 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5 | >100 |

| Nocardia otitidiscaviarum | IFM 0239 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 6 | >100 |

| Nocardioides albus | JCM 3185 | 1.0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 10 | >100 |

| Rhodococcus equi | ATCC 14887 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 15 | >100 |

| Rhodococcus equi | CS402 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 10 | >100 |

| Tsukamurella paurometabola | IFM 0811 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3 | >100 |

Plates were incubated at 30°C for 96 h. Organisms were provided by Y. Mikami, except strains ATCC 14887 and ATCC 25593 (N. Ferreira) and CS402 (N. Tomioka).

On BHI solid medium the MIC of each of the four azoles for R. equi strain ATCC 14887 was ≤1 μg/ml; the MIC for N. brasiliensis was 0.5 to 1.0 μg/ml (Table 1). The least susceptibility, an MIC of 2 μg/ml, was observed for M. vaccae with bifonazole. Ketoconazole, an orally administered imidazole, was less effective: most MICs were ∼10 μg/ml. Fluconazole and voriconazole showed no inhibitory effects in these experiments. We included 4-nitroimidazole in our testing since the MIC for M. tuberculosis has been reported to be ∼20 μg/ml, but no inhibitory effect was observed at 100 μg/ml. H. pylori is highly susceptible to metronidazole (14), but this compound did not affect the growth of the strains we investigated. Azole MICs were not medium dependent: MICs on BHI medium were similar to those on Luria-Bertani or SD medium. Comparison with fungi on SD plates showed that these bacterial strains were in every case inhibited at lower drug concentrations than those at which the fungal strains were inhibited; for example, the econazole MICs were 5 μg/ml for C. albicans, 2 μg/ml for Fusarium sp., and 3 μg/ml for Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Aspergillus niger. Fluconazole and voriconazole had MICs similar to or lower than these values against the fungal strains. Nystatin also targets ergosterol and interferes with fungal membrane integrity. However, instead of blocking synthesis this polyene binds to the ergosterol, leading to formation of a pore, allowing leakage of intracellular fungal ions and macromolecules (5). We tested the effect of nystatin on these bacterial strains, but no inhibition was observed, suggesting limits to comparability between azole action on prokaryotic nocardioforms and eukaryotic fungi.

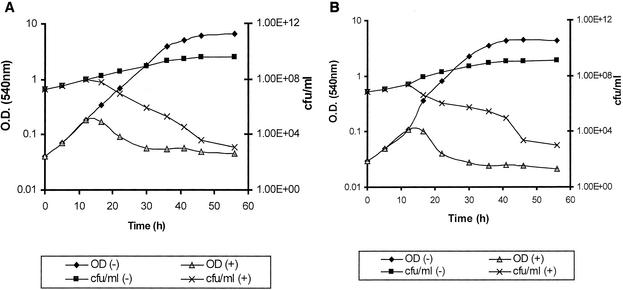

The efficacy of antimicrobial chemotherapy is greatly diminished in the face of selection of resistant mutants: the average mutation rate in M. tuberculosis for resistance to isoniazid is 1 in 10−5 to 1 in 10−6; the corresponding figures for rifampin and ethambutol are 1 in 10−8 and 1 in 10−4, respectively (12). We attempted to select mutants resistant to 10 μg of each of the four imidazoles/ml; approximately 1 × 109 CFU of M. vaccae, 1 × 109 CFU of N. brasiliensis, or 4 × 109 CFU of R. equi in BHI broth were challenged with each of the antifungals, but no clones resistant to this level of drug were obtained. Similar results were obtained from cultures spread on BHI plates. These experiments were repeated four or more times, indicating that resistance to these compounds arises extremely rarely. At concentrations about 10 times the MIC the imidazoles were bactericidal (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Response to clotrimazole (10 μg/ml) challenge for cultures of R. equi ATCC 14887 (A) and D. maris JCM 6166 (B) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of an imidazole. The drug was added at 12 h (third data point). The scales of the y axes are logarithmic.

Recently a sterol biosynthetic pathway has been identified in mycobacteria (13) and the putative target was identified (7). Our results suggest that this pathway is present in nocardioform bacteria too. The drugs we determined to be bactericidal at low concentrations are for topical rather than systemic use (6), so they might be tested against mycetomas, infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue by Nocardia and related organisms Actinomadura madurae and Streptomyces somaliensis (16). Since antifungal imidazoles are routinely used on humans, their pharmacology is well established. Thus there is a realistic potential for their use in treatment of infections by these opportunistic pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Mikami for helpful discussions and providing strains. We are indebted to Pfizer Laboratories Ltd. for generously supplying voriconazole and fluconazole.

This work was supported by a grant from the Medical Research Council of South Africa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akan, H., M. Akova, H. Ataoglu, G. Aksu, O. Arslan, and H. Koc. 1998. Rhodococcus equi and Nocardia brasiliensis infection of the brain and liver in a patient with acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:737-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bemer-Melchior, P., A. Haloun, P. Riegel, and H. B. Drugeon. 1998. Bacteremia due to Dietzia maris in an immunocompromised patient. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1340-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark, N. M., D. K. Braun, A. Pasternak, and C. E. Chenoweth. 1995. Primary cutaneous Nocardia otitidiscaviarum infection: case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1266-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clotet, B., G. Sierra, and A. Erice. 1993. Rhodococcus equi infection in HIV-infected patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 6:429-430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelstein, A., and R. Holz. 1973. Aqueous pores created in thin lipid membranes by the polyene antibiotics nystatin and amphotericin B. Membranes 2:377-408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgopapadakou, N. H., and T. J. Walsh. 1996. Antifungal agents: chemotherapeutic targets and immunological strategies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:279-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guardiola-Diaz, H. M., L. A. Foster, D. Mushrush, and A. D. Vaz. 2001. Azole-antifungal binding to a novel cytochrome P450 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for treatment of tuberculosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 61:1463-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hachem, R., I. Raad, K. V. Rolston, E. Whimbey, R. Katz, J. Tarrand, and H Libshitz. 1996. Cutaneous and pulmonary infections caused by Mycobacterium vaccae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23:173-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey, R. L., and J. C. Sunstrum. 1991. Rhodococcus equi infection in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hondalus, M. K. 1997. Pathogenesis and virulence of Rhodococcus equi. Vet. Microbiol. 56:257-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsueh, P. R., C. C. Hung, L. J. Teng, M. C. Yu, Y. C. Chen, H. K. Wang, and K. T. Luh. 1998. Report of invasive Rhodococcus equi infections in Taiwan, with an emphasis on the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:370-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwin, L. L., and L. S. Rickman. 1995. New, unfamiliar drugs for suspected drug-resistant tuberculosis. Infect. Med. 12:32-39. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson, C. J., D. C. Lamb, D. E. Kelly, and S. L. Kelly. 2000. Bactericidal and inhibitory effects of azole antifungal compounds on Mycobacterium smegmatis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 192:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamp, K. C., C. D. Freeman, N. E. Klutman, and M. K. Lacy. 1999. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the nitroimidazole antimicrobials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 36:353-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordmann, P., E. Rouveix, M. Guenounou, and M. H. Nicolas. 1992. Pulmonary abscess due to a rifampin and fluoroquinolone resistant Rhodococcus equi strain in a HIV infected patient. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11:557-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palestine, R. F., and R. S. Rogers. 1982. Diagnosis and treatment of mycetoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 6:107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pidoux, O., J. N. Argenson, V. Jacomo, and M. Drancourt. 2001. Molecular identification of a Dietzia maris hip prosthesis infection isolate. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2634-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richet, H. M., P. C. Craven, J. M. Brown, B. A. Lasker, C. D. Cox, M. M. McNeil, A. D. Tice, W. R. Jarvis, and O. C. Tablan. 1991. A cluster of Rhodococcus (Gordona) bronchialis sternal-wound infections after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 324:104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabo, J. A., and S. M. Abdel-Rahman. 2000. Voriconazole: a new triazole antifungal. Ann. Pharmacother. 34:1032-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salinas-Carmona, M. C. 2000. Nocardia brasiliensis: from microbe to human and experimental infections. Microbes Infect. 2:1373-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarzier, J. S., J. N. Greene, R. L. Sandin, A. S. Spiers, P. J. Emmanuel, R. E. Valder, M. E. Gombert, and A. L. Vincent. 1998. Disseminated Nocardia brasiliensis infection in an immuno-compromised patient. Cancer Control 5:64-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sud, I. J., and D. S. Feingold. 1982. Action of antifungal imidazoles on Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:470-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun, Z., and Y. Zhang. 1999. Antituberculosis activity of certain antifungal and antihelmintic drugs. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:319-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Recklinghausen, G., C. Di Maio, and R. Ansorg. 1993. Activity of antibiotics and azole antimycotics against Helicobacter pylori. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 280:279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yazawa, K., Y. Mikami, A. Maeda, M. Akao, N. Morisaki, and S. Iwasaki. 1993. Inactivation of rifampin by Nocardia brasiliensis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1313-1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida, Y. 1988. Cytochrome P450 of fungi: primary target for azole antifungal agents. Curr. Top. Med. Mycol. 2:388-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]