Abstract

The 5′ cap and 3′ poly(A) tail of eukaryotic mRNAs act synergistically to enhance translation. This synergy is mediated via interactions between eIF4G (a component of the eIF4F cap binding complex) and poly(A) binding protein (PABP). Paip2 (PABP-interacting protein 2) binds PABP and inhibits translation both in vitro and in vivo by decreasing the affinity of PABP for polyadenylated RNA. Here, we describe the functional characteristics of Paip2B, a Paip2 homolog. A full-length brain cDNA of Paip2B encodes a protein that shares 59% identity and 80% similarity with Paip2 (Paip2A), with the highest conservation in the two PABP binding domains. Paip2B acts in a manner similar to Paip2A to inhibit translation of capped and polyadenylated mRNAs both in vitro and in vivo by displacing PABP from the poly(A) tail. Also, similar to Paip2A, Paip2B does not affect the translation mediated by the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of hepatitis C virus (HCV). However, Paip2A and Paip2B differ with respect to both mRNA and protein distribution in different tissues and cell lines. Paip2A is more highly ubiquitinated than is Paip2B and is degraded more rapidly by the proteasome. Paip2 protein degradation may constitute a primary mechanism by which cells regulate PABP activity in translation.

Keywords: gene expression, protein synthesis, initiation factors, ubiquitination, proteasome

INTRODUCTION

Translational control plays an essential role in cell growth, differentiation, and development (Conlon and Raff 1999; Gingras et al. 1999). Translation in eukaryotes is regulated primarily at the level of initiation, and the 3′ poly(A) tail and 5′ cap structure (m7GpppN, where m is a methyl group and N is any nucleotide) of the mRNA play an essential role. The cap structure facilitates mRNA binding to the ribosome through its interaction with the eukaryotic initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) (Conlon and Raff 1999; Mathews et al. 2000). In mammals, eIF4F is a protein complex composed of three subunits: eIF4E, the cap binding protein; eIF4A, an RNA-dependent ATPase and bidirectional helicase; and eIF4G, a modular protein that binds eIF4E and eIF4A, and recruits the 40S ribosomal subunit by binding eIF3 (Gingras et al. 1999; Hershey and Merrick 2000; Mathews et al. 2000). The polyadenylated 3′ end of the mRNA interacts with the poly(A) binding protein (PABP). PABP is comprised of four N-terminal RNA recognition motifs (RRM) and a proline-rich C-terminal portion containing a ∼70-amino-acid conserved domain (PABC). PABP is a phylogenetically conserved protein that is essential in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sachs et al. 1987; Sachs 2000). PABP and eIF4G physically interact, and this interaction is required for the cap and poly(A) to stimulate translation initiation synergistically. The PABP–eIF4G interaction leads to the circularization of the mRNA (Tarun and Sachs 1996; Imataka et al. 1998; Sachs 2000), but it is not yet clear whether translational stimulation is mediated by mRNA circularization directly or as a result of an increase in the affinity of initiation factors for the mRNA (Kahvejian et al. 2005).

PABP activity is modulated by two PABP-interacting proteins (Paips), Paip1 and Paip2. Paip1 contains two binding domains for PABP (see below) that lie on either side of a region similar to the central portion of eIF4G, which contains one of its two known eIF4A binding sites (Craig et al. 1998; Roy et al. 2002). In COS-7 cells, Paip1 also interacts with eIF4A and stimulates translation of a reporter luciferase mRNA (Craig et al. 1998).

Paip1 contains two binding sites for PABP, PAM1 and PAM2 (for PABP-interacting motifs 1 and 2) (Roy et al. 2002). PAM2 consists of a 15-amino-acid stretch residing in the N terminus, and PAM1 encompasses a larger C-terminal acidic-amino-acid-rich region. PABP also contains two Paip1 binding sites, one located in RNA recognition motifs 1 and 2 and the other located in the C-terminal domain. Paip1 binds to PABP with a 1:1 stoichiometry.

Paip2 is a highly acidic protein (pI = 3.9) of 127 amino acid with a predicted molecular weight of ∼14.5 kDa (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b). Paip2 contains two independent PABP binding sites (PAMs): PAM2 in its C terminus, which shares high homology with Paip1 (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a; Roy et al. 2002) and binds the conserved PABC region, and PAM1, which resides in a highly acidic domain in the middle of the protein and interacts with PABP RRMs 2 and 3 (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a). PABP and Paip2 form a heterotrimeric complex containing one PABP molecule and two Paip2 molecules (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a). Paip2 competes with Paip1 for PABP binding and inhibits translation in vitro and in vivo and decreases the affinity of PABP for polyadenylated RNAs in vitro (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b). Although Paip2 does not contain any RNA binding motifs, it has been shown to interact with various mRNAs, promoting its destabilization (GLUT5) (Gouyon et al. 2003) or its stabilization (VEGF) (Onesto et al. 2004).

Here, we describe a homolog of Paip2, Paip2B, a 123-amino-acid protein that is 80% similar (59% identical) to Paip2 (henceforth denoted Paip2A). In particular, the PABP binding sites within these homologs are highly similar, and in fact, PABP binds each homolog in a similar manner. Similar to Paip2A, Paip2B displaces PABP from the poly(A) tail of capped/polyadenylated mRNAs, thereby inhibiting translation both in vitro and in vivo. Quantitative RT-PCR data and Northern, Western, and far-Western blot analyses demonstrate that Paip2A and Paip2B differ in their intracellular concentration. Differential tissue expression and limited protein sequence divergence suggest that Paip2A and Paip2B may function in a tissue-specific manner and respond to distinct stimuli.

The ubiquitin/proteasome pathway is the primary nonlysosomal route for intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotes. This pathway modulates the level of many specific proteins that regulate vital cellular processes such as cell-cycle progression, transcription, and antigen processing (Hershko and Ciechanover 1998). Our results show that both Paip2B and Paip2A become ubiquitinated when overexpressed in cells and that ubiquitination targets them for degradation by the proteasome. Paip2A becomes ubiquitinated to a greater extent and therefore is more rapidly degraded than Paip2B.

RESULTS

Cloning and analysis of Paip2B cDNA and protein sequences

The human Paip2A amino acid sequence (GenBank accession no. AF317675) was used to search GenBank for related proteins using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990). The search revealed the protein sequence KIAA1155 (GenBank accession no. AB032981.1) derived from a cDNA clone from a human brain library (Hirosawa et al. 1999). The cDNA was 6286 bp and encoded a 123-amino-acid polypeptide with a predicted molecular weight of ∼14.2 kDa. The 5′ and 3′ UTRs were 167 bp and 5747 bp, respectively, and contained several canonical (one at position 6270–6275, 16 nt upstream from the poly(A) tail) and noncanonical polyadenylation signals. The protein encoded by this cDNA was designated Paip2B. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of Paip2B with Paip2A (Fig. 1A) shows 59% identity (black shading) and 80% similarity (black plus gray shading). The similarity between these two proteins is most evident in the central and C-terminal portions, which contain the PAMs (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a).

FIGURE 1.

Paip2B and Paip2A protein sequence alignment. (A) The amino acid sequences corresponding to human Paip2B and Paip2A proteins were aligned by using the CLUSTAL W (1.8) program. Identical residues are shown in black, similar residues are in gray, and sequence gaps are indicated by dashes. The proteins share 59% identity and 80% similarity. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of Paip2 proteins from different organisms using CLUSTAL W (1.8). Asterisks indicate residues that are completely conserved. Black shading indicates that the residues are present in at least six of the nine sequences. Dark gray shading indicates very conservative substitutions, and light gray shading indicates less conservative substitutions. (C) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of Paip2 proteins using the two-parameter model of Kimura. The numbers at the nodes indicate bootstrap percentages after 1000 replications of bootstrap sampling. The bar indicates genetic distance.

The Paip2A and Paip2B amino acid sequences were used to perform BLAST searches in the GenBank to identify interspecies homologs. Sequences of overall high similarity (GenBank accession numbers are given in Materials and Methods) were aligned by using the CLUSTAL W program (Fig. 1B; Thompson et al. 1994). These proteins share extensive identity in the C-terminal two thirds of the protein (black shading) containing the two PAMs, while the N terminus shows very appreciable differences. Phylogenetic trees were generated by using Kimura two-parameter distance and the neighbor-joining methods. Five different lineages, which are strongly supported by bootstrap values, are shown (Fig. 1C). Human and mouse Paip2B are closely related and cluster with frog Paip2. Surprisingly, the Paip2 zebrafish cluster (two close, but different Paip2 sequences, designated as Paip2 zebrafish-1 and -2), supported by a bootstrap value of 81%, is closer to Paip2B than to Paip2A sequences. Human and mouse Paip2A are closely related and constitute a monophyletic group while salmon and Drosophila melanogaster Paip2 cluster separately.

Characterization of Paip2B

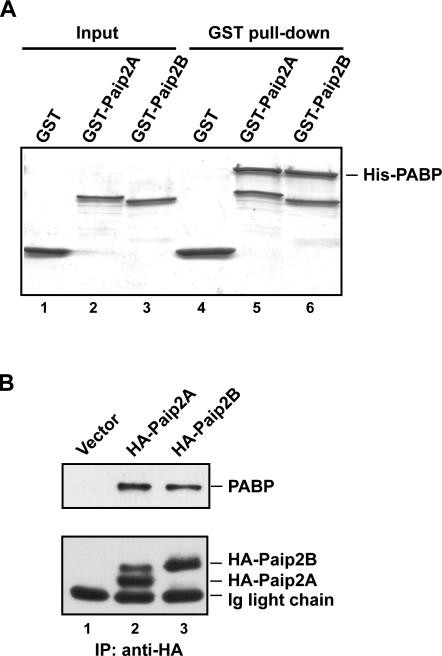

To confirm that Paip2B, similar to its homolog Paip2A, interacts with PABP, GST pull-down experiments were performed by using purified His-PABP and GST, GST-Paip2B, or GST-Paip2A (Fig. 2A). GST alone was unable to interact with PABP (Fig. 2A, lane 4), while GST-Paip2B and GST-Paip2A pulled down His-PABP at similar levels (Fig. 2A, lanes 5,6). This interaction was also assayed via transient transfection of 293T cells with HA-Paip2B or HA-Paip2A and subsequent coimmunoprecipitation with endogenous PABP (Fig. 2B). Anti-HA immune complexes obtained from cells transfected with an empty vector did not contain PABP (Fig. 2B, lane 1), whereas the respective complexes obtained from cells transfected with plasmids encoding HA-Paip2B or HA-Paip2A contained similar amounts of both endogenous PABP and HA-Paip2 proteins (Fig. 2B, lanes 2,3). In Figure 2B, lane 2, there is a slower migrating band in addition to HA-Paip2A, which appeared in some, but not all, experiments and may be explained by a posttranslational modification of the protein, like ubiquitination (see below). These experiments demonstrate that Paip2B and Paip2A interact similarly with, and can bind a similar amount of recombinant PABP in vitro and endogenous PABP in vivo.

FIGURE 2.

Paip2B binds PABP in vitro and in vivo. (A) In GST pull-down experiments, complexes containing recombinant His-PABP and either GST, GST-Paip2A, or GST-Paip2B were immobilized by using glutathione-Sepharose beads, as described in the Materials and Methods. Bound proteins were eluted with Laemmli loading buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. (B) 293T cells were transfected with plasmids containing either no insert or encoding HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-HA. The immune complexes were analyzed by Western blot using anti-PABP (upper panel) or anti-HA (lower panel).

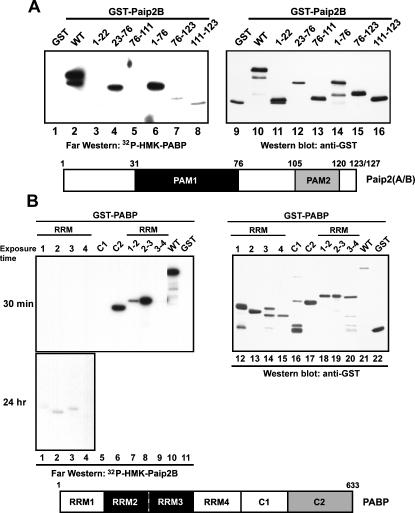

The Paip2B–PABP interaction was further characterized by analyzing the respective binding sites in each protein using far-Western blotting. Based on previous results for Paip2A–PABP interactions (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a), Paip2B fragments were expressed and purified as GST fusion proteins. Approximately equivalent molar amounts of protein were resolved on a gel and transferred to a membrane that was probed with 32P-HMK-PABP for far-Western analysis and anti-GST for Western blotting (loading control) (see Fig. 3A). GST-Paip2B (WT) and Paip2B fragments 1–76 and 23–76 exhibited strong interaction with PABP (Fig. 3A, lanes 2,4,6) compared with substantially weaker interactions for fragments 76–123 and 111–123 (Fig. 3A, lanes 7,8). GST alone or fragments 1–22 or 76–111 showed no interaction (Fig. 3A, lanes 1,3,5). These results are consistent with those previously shown for Paip2A (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a) in that PABP binds Paip2B at two independent sites, one located in the central acidic portion of the protein (residues 23–76) and another near the C terminus (residues 111–123).

FIGURE 3.

Identification of respective binding sites within PABP and Paip2B. (A) Affinity-purified GST, GST-Paip2B (WT), and GST-Paip2B fragments were resolved by SDS-PAGE and assayed for PABP binding by far-Western blotting using a 32P-HMK-PABP probe (left panel) and by Western blotting using a polyclonal antibody to GST (for loading control, right panel). (B) Purified GST, GST-PABP (WT), and GST-PABP fragments (different combinations of RRM and C-terminal regions) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for Paip2B binding by far-Western blotting using a 32P-HMK-Paip2B probe (left panel) and by Western blotting using a polyclonal antibody to GST (for loading control, right panel). Schematic representations of Paip2A/B and PABP shown below the respective panels identify the binding sites.

Next, GST fusion proteins corresponding to PABP fragments were constructed and analyzed by far-Western analysis using 32P-HMK-Paip2B as a probe (Fig. 3B, left upper and bottom panels) and by Western blot using anti-GST (Fig. 3B, right panel). GST-PABP (WT) and fusion proteins containing RRMs 2–3 or the C2 region exhibited strong binding to the Paip2B probe (Fig. 3B, lanes 6,8,10), whereas those containing RRMs 1–2, 3–4, 2, or 3 showed weaker binding (Fig. 3B, lanes 2,3,7,9). GST alone or fusion proteins containing RRMs 1 or 4 or C1 failed to bind Paip2B (Fig. 3B, lanes 1,4,5,11). Thus, Paip2B interacts with PABP RRM 2–3 and the C2 region as demonstrated previously for Paip2A (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a).

Functional characterization of Paip2B

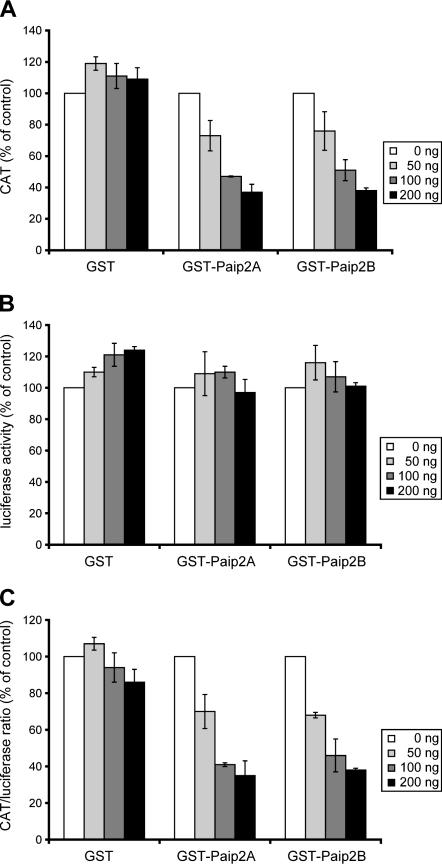

The data in Figures 2 and 3 indicate that Paip2B and Paip2A bind PABP through their interaction with the same binding motifs/regions. To test whether these findings reflect Paip2B function, we studied the effect of Paip2B on the translation of CAT-HCV IRES-luc mRNA (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b; Svitkin et al. 2001), a capped and polyadenylated bicistronic mRNA, by using a Krebs-2 cell-free in vitro translation system (Svitkin et al. 1984) as previously described for Paip2A (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b). This bicistronic mRNA encodes chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) in the first cistron, which is translated in a cap- and poly(A)-dependent manner. The second cistron corresponds to luciferase mRNA, which is translated under the control of the HCV IRES that is eIF4G-independent (Pestova et al. 1998). GST-Paip2B and GST-Paip2A, but not GST alone, specifically inhibited CAT ORF translation in a dose-dependent manner without affecting luciferase ORF translation from the second cistron (Fig. 4A,B ). Since luciferase ORF translation was not affected, the values measured for luciferase activity were used to normalize each assay for the possible small variations in the amount of mRNA added. Thus, the inhibitory activity of Paip2 proteins was calculated as the ratio of CAT cistron translation to that measured for luciferase cistron (Fig. 4C). The results suggest that both Paip2 proteins inhibit cap-dependent translation to the same extent.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of Paip2B on in vitro translation of capped and polyadenylated bicistronic CAT-HCV IRES-luciferase mRNA. Capped and polyadenylated bicistronic CAT-HCV IRES-luciferase mRNA was translated by using Krebs-2 cell-free translation reactions in the presence of increasing concentrations of GST (control), GST-Paip2B, or GST-Paip2A. (A) First cistron, cap-dependent, and poly(A)-dependent translation. (B) Second cistron, cap-independent, and poly(A)-independent translation. (C) First and second cistron translation ratio. CAT protein and luciferase activity values represent the average of at least three independent experiments. Error bars, SD of mean values.

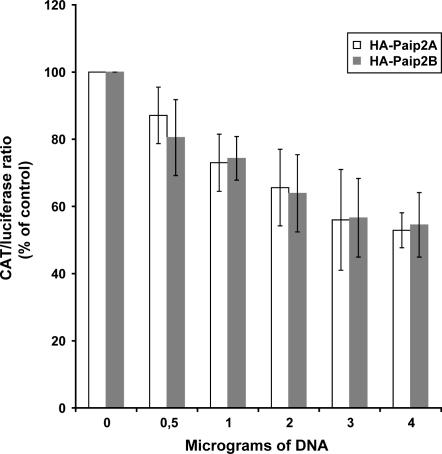

To study the effect of Paip2 proteins in vivo, Paip2B and Paip2A were overexpressed in 293T cells by transient cotransfection with a plasmid (pcDNA3-CAT-HCV IRES-Luc) encoding the same bicistronic mRNA used for the in vitro translation assays (Rivas-Estilla et al. 2002). Cotransfection with increasing amounts of plasmids encoding HA-Paip2B or HA-Paip2A elicited a dose-dependent inhibition of CAT protein production, whereas luciferase activity was not affected (data not shown). Luciferase activity was used to normalize for the amount of mRNA produced in cells, and the results were expressed as the ratio between CAT and luciferase activities (Fig. 5). Paip2A and Paip2B inhibited translation almost identically, leading to a ∼50% reduction in CAT cistron translation at the highest amount of DNA used.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of Paip2B on in vivo translation of capped and polyadenylated bicistronic CAT-HCV IRES-luciferase mRNA. 293T cells were cotransfected with a fixed amount of plasmid encoding bicistronic CAT-HCV IRES-luciferase mRNA and increasing amounts of plasmids encoding HA-Paip2B or HA-Paip2A. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were lysed and CAT expression and luciferase activity were measured in the lysates. The results are presented as the ratio of the expression of CAT to that of luciferase. CAT protein and luciferase activity values represent the average of at least three independent experiments. Error bars, SD of mean values.

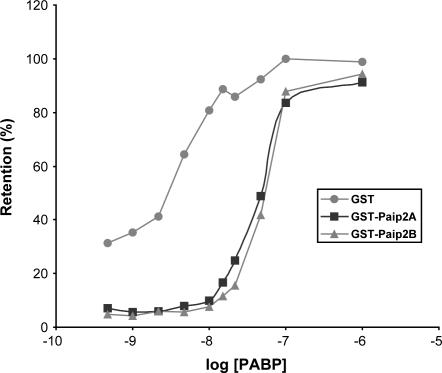

The mechanism proposed for Paip2A inhibition of polyadenylated mRNA translation is the displacement of PABP from the poly(A) tail (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b). We, therefore, tested Paip2B-mediated displacement of PABP from the poly(A) tail and the kinetics thereof. Binding curves were calculated from assays in which the concentration of PABP was varied, while that of either GST-Paip2B, GST-Paip2A, or GST (negative control) was held constant. The kinetics of PABP displacement from the poly(A) tail were identical for Paip2B and Paip2A (Fig. 6). We conclude that Paip2B and Paip2A are homologs that exhibit nearly identical function in cells in that they interact with PABP via the same regions and have the same effect on translation both in vitro and in vivo.

FIGURE 6.

Paip2B, similar to Paip2A, displaces PAPB from poly(A) RNA. Filter binding assays were performed as described in the Materials and Methods using constant concentrations of 32P-poly(A) RNA (3000 cpm, 0.01 nM) and either GST-Paip2A, GST-Paip2B, or GST (100nM), and increasing concentrations of PABP, as indicated. Radioactivity in the spots was counted in a scintillation counter, and the results were plotted as the percentage of radioactive probe retained on the filter. The values represent the mean of three independent experiments that yielded very similar results.

Paip2B and Paip2A mRNA distribution in different human tissues

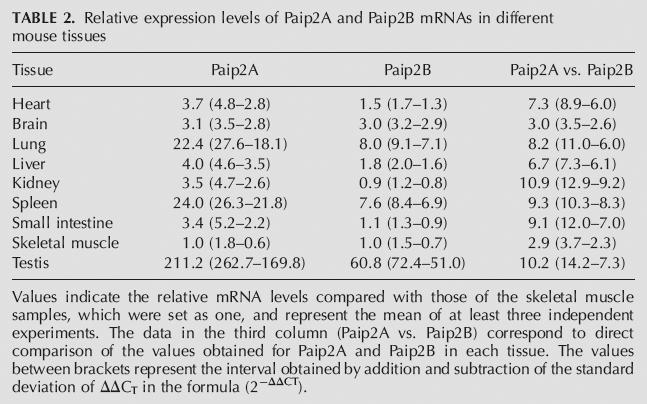

The high degree of amino acid sequence homology between Paip2B and Paip2A as well as their near-identical effect on translation prompted us to investigate differences in their mRNA expression patterns in various human tissues using Northern blot analysis (Fig. 7) and quantitative RT-PCR (Tables 1, 2). The majority of tissues analyzed express three distinct isoforms of the Paip2B mRNA, one of ∼6.5 kb corresponding to the size of the cloned cDNA and two additional species of ∼1.5 and ∼0.6 kb (Fig. 7). The distribution of the three isoforms showed tissue-specific differences in that the longest isoform predominated in the brain, whereas the shortest was more abundant in the liver and testis. To further study the relative levels of Paip2A and Paip2B mRNAs in different human and mouse tissues, we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR by using gene specific primers lying in the open reading frame of both Paip2 mRNAs and of GAPDH mRNA as a housekeeping gene internal control. In human tissues (Table 1), Paip2A mRNA was especially abundant in the testis, but high levels were also found in the cervix, lung, brain, ovary, placenta, adipose tissue, thymus, and thyroid; Paip2B mRNA showed the highest level in the brain and relative high level in other tissues such as the cervix, heart, liver, ovary, kidney, prostate, and testis. What is clear from these data is that Paip2A mRNA appears to be significantly more abundant than is Paip2B mRNA in all the tissues analyzed, ranging from about fivefold in the heart to ∼300-fold in the placenta. In mouse tissues both Paip2A and Paip2B mRNAs were especially abundant in the testis, lung, and spleen, showing similar levels in the rest of the organs tested except for the brain, where Paip2B mRNA is more abundant (Table 2). As in human tissues, Paip2A mRNA levels are higher than those of Paip2B in all the tissues studied (threefold to 11-fold).

Figure 7.

Paip2B and Paip2A mRNA distribution. Membranes containing electrophoretically separated mRNAs from different human tissues (Human Multiple Tissue Northern blot membranes from Clontech), were hybridized by using labeled cDNA probes specific for Paip2B, Paip2A, and actin, as described in the Materials and Methods.

TABLE 1.

Relative expression levels of Paip2A and Paip2B mRNAs in different human tissues

TABLE 2.

Relative expression levels of Paip2A and Paip2B mRNAs in different mouse tissues

Paip2B and Paip2A protein expression in tissues and cell lines

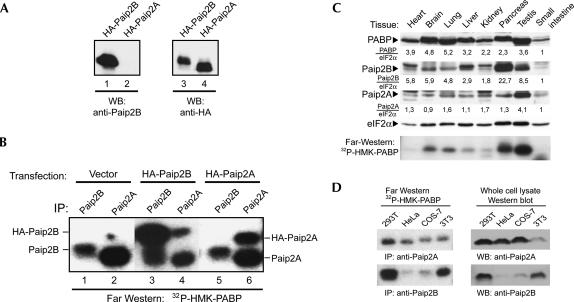

To distinguish between Paip2B and Paip2A, we raised a polyclonal serum against Paip2B by immunizing rabbits with a GST fusion polypeptide containing the first 21 residues of Paip2B, the region of highest sequence divergence compared with Paip2A. The specificity of this antiserum was verified by Western blot as well as immunoprecipitation followed by far-Western blotting using PABP as a probe (Fig. 8). The anti-Paip2B serum recognized HA-Paip2B but not HA-Paip2A in 293T cells (Fig. 8A), while anti-HA detected both proteins. In transfected 293T cells, anti-Paip2B immunoprecipitated endogenous Paip2B and HA-Paip2B, but not endogenous or HA-tagged Paip2A (Fig. 8B). The presence of Paip2 proteins in the immune complexes was evidenced by far-Western analysis using PABP as a probe. Endogenous Paip2B migrated with a higher apparent molecular weight than did Paip2A, thus allowing visual distinction. The antiserum against full-length Paip2A immunoprecipitated the overexpressed form of Paip2B, but with very low affinity (Fig. 8B, lanes 3,4). Given that the amount of anti-Paip2B used was not limiting (Fig. 8B, lane 3), these data suggest that Paip2A expression in these cells is much higher than is Paip2B (Fig. 8B, lanes 1,2).

FIGURE 8.

Characterization of an antibody specific for Paip2B: tissue-specific distribution of Paip2 proteins. A Paip2B-specific antibody was obtained by immunizing rabbits with GST-Paip2B (residues 1–21). (A) 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B, and cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot using anti-Paip2B and anti-HA. (B) 293T cells were transfected with plasmids containing either no insert (negative control) or encoding either HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-Paip2A or anti-Paip2B, as indicated. The immune complexes were analyzed by far-Western blotting using 32P-HMK-PABP as a probe. The electrophoretic migration of endogenous and HA-tagged Paip2 proteins is indicated. (C) Equal amounts of total protein (150 μg) from mouse tissue extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against Paip2B, Paip2A, PABP, or eIF2α (as a loading control), as indicated, and by far-Western blot using a 32P-HMK-PABP probe (bottom panel). The values under the Western blot panels represent the intensities of bands in each tissue normalized with respect to the corresponding eIF2alpha bands. For comparison, the value obtained for the small intestine sample was set as one. (D) 293T, HeLa, COS-7, and NIH 3T3 cell extracts were prepared, and equal amounts of protein were subjected either to immunoprecipitation using anti-Paip2B or anti-Paip2A antibodies or to SDS-PAGE (50 μg of whole-cell extract) and Western blotting using the same antibodies. The immune complexes were analyzed by far-Western blotting using a 32P-HMK-PABP probe.

To compare Paip2B and Paip2A protein levels in different tissues and cell lines, whole-cell extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blotting and far-Western analysis either directly or after immunoprecipitation (Fig. 8C,D). Extracts of different tissues were examined for Paip2B and Paip2A expression by Western blot. As expected from the mRNA data, the levels of both proteins were high in the testis. Paip2A was present in very similar levels in the rest of the tissues analyzed. Moderately high levels of Paip2B were found in the brain, heart, and lung and very high levels were found in the pancreas. Far-Western analysis (Fig. 8C, bottom panel), with PABP used as a probe, yielded a pattern that corresponded very well to that observed for Paip2A by Western blotting, thus suggesting that Paip2A is more abundant than is Paip2B in all the tissues analyzed. The expression of both proteins in four cell lines was also assessed. While Paip2A was expressed nearly equally in all the cell lines, with only a slightly higher level in 293T (Fig. 8D, upper panels), Paip2B was much more abundant in 293T and NIH 3T3 cells than in HeLa and COS-7 cells (Fig. 8D, bottom panels).

Ubiquitination differentially regulates Paip2A and Paip2B expression

While studying the effects of Paip2B and Paip2A on reporter mRNA expression, it became clear to us that HA-Paip2B expression was always higher than that of HA-Paip2A (Fig. 9A). Given that both proteins were expressed by using the same vector, we investigated whether the differential protein expression reflected differences in their half-life. HA-PABP, HA-Paip2A, or HA-Paip2B was transfected in HEK 293T cells that were pulsed with [35S]methionine and chased in the absence or the presence of two distinct proteasome inhibitors, LLnL and MG132 (Fig. 9B,C). After 5 h, nearly all the labeled Paip2A was degraded, while Paip2B was only slightly diminished (Fig. 9B,C). The presence of the proteasome inhibitors increased the stability of both proteins, although Paip2A stability increased to a greater extent. These results are in agreement with the recent report of Yoshida et al. (2006). PABP levels were not affected by proteasome inhibitors. Proteins whose levels are regulated by the proteasome are targeted for degradation by covalent ligation to polyubiquitin complexes (Hershko and Ciechanover 1998). Paip2 ubiquitination was assessed by coexpression of HA-tagged Paip2 proteins with His6-ubiquitin in HEK 293T cells. Cells were treated with proteasome inhibitor and lysed in a denaturing buffer to prevent degradation or deubiquitination of the protein–ubiquitin conjugates, as well as noncovalent protein–protein interactions (Treier et al. 1994). After purification of His6-ubiquitin-containing proteins, polyubiquitinated HA-Paip2A and HA-Paip2B were detected as discrete bands and in high-molecular-weight smears (Fig. 9D). In good agreement with the results in Figure 9, B and C, the relative amount of ubiquitinated Paip2A was much higher than that of ubiquitinated Paip2B, and the levels of both proteins increased in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor. Furthermore, some ubiquitinated forms of Paip2A were observed in the whole-cell lysate. To demonstrate that the ubiquitination of these proteins was independent of their fusion to the HA tag and to show that the untagged and endogenous Paip2 proteins are also ubiquitinated, we expressed His6-ubiquitin alone (to assess endogenous Paip2 proteins ubiquitination) or in combination with either HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B, or untagged Paip2A or Paip2B. In each case, the untagged and HA-tagged proteins were ubiquitinated in the absence or presence of proteasome inhibitor. Endogenous Paip2A showed the characteristic pattern of ubiquitination after treatment with the proteasome inhibitor. Ubiquitination of endogenous Paip2B was not observed, most likely due to its lower level of expression compared to Paip2A and to the lower ubiquitination observed even when the protein is overexpressed. Taken together, these results show that the ubiquitin/proteasome degradation pathway impacts Paip2A to a greater extent than Paip2B, since its half-life is considerably shorter than that of Paip2B.

FIGURE 9.

Differential regulation of Paip2A and Paip2B protein levels. (A) HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected by using increasing amounts of plasmids encoding HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B, as indicated. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were lysed and lysates were analyzed by Western blot using anti-HA. Samples from two independent experiments were loaded. (B) HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged proteins (PABP, Paip2A, or Paip2B) and metabolically labeled for 2 h with [35S]methionine and chased with cold methionine for 5 h in the absence or presence of 50 μM LLnL (proteasome inhibitor). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody, and immune complexes were washed and resolved by SDS-PAGE gels, dried, and exposed to X-ray film. (C) The same procedure as in B, but cells were metabolically labeled for 1 h with [35S]methionine in the absence or presence of 10 μM MG132 (proteasome inhibitor) and were chased or not chased with cold methionine for 5 h, in the same conditions. After immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody, immune complexes were first washed and proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and exposed to X-ray film (upper panel). After autoradiography membranes were analyzed by Western blot using anti-HA and anti-PABP antibodies (lower panels) as indicated. Numbers under the upper autoradiography panel represent the intensity of bands in each lane. For comparison, the values obtained at chase time 0 in the absence of MG132 were taken as 100%. The numbers between brackets were obtained when the values at chase time 0 in the presence of MG132 were taken as 100%. (D) Cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding either HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B and a plasmid encoding His6-ubiquitin. At the indicated times before lysis, some of the cells were treated with 50 μM LLnL. Cells were lysed in guanidine-HCl denaturing buffer, and His6-tagged complexes were purified by using a metal affinity resin as described in the Materials and Methods. Purified proteins were eluted from the resin with 1× Laemmli sample buffer, and the presence of HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B was revealed by Western blotting with anti-HA (upper panel). Aliquots of cell lysates were also analyzed in the same way for the presence of HA-Paip2A and HA-Paip2B. (E) The same procedure as in D (upper panel), but cells were also transfected with an empty plasmid or with plasmids encoding either untagged Paip2A or Paip2B in combination with the His6-ubiquitin plasmid. Half of the cells were treated with LLnL for 6 h before lysis. Proteins were visualized by Western blot using appropriate specific antisera for Paip2A and Paip2B proteins.

DISCUSSION

Paip2 is an inhibitor of translation both in vitro and in vivo. Paip2 displaces PABP from the poly(A) tail and competes with Paip1 for PABP binding (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b; Roy et al. 2002), thus abrogating mRNA circularization, which is dependent on cross talk between the 5′ and 3′ ends via PABP-eIF4G and PABP-Paip1-eIF4A interactions (Sachs et al. 1987; Tarun and Sachs 1996; Craig et al. 1998; Imataka et al. 1998; Gingras et al. 1999; Hershey and Merrick 2000; Mathews et al. 2000; Sachs 2000). Here we described a homolog of Paip2, termed Paip2B (Paip2 is now referred to as Paip2A). Paip2B mRNA encodes a 123-amino-acid polypeptide, four residues shorter than Paip2A. The two proteins exhibit extensive sequence conservation within the PABP binding sites, PAM1 and PAM2. The most divergent sequence corresponds to the 27 residues nearest the N terminus and may constitute a target for differential regulation of these two homologs.

Homologs of Paip2A and Paip2B have been identified, by searching in the GenBank, in D. melanogaster, frogs, and various fish species such as salmon and zebrafish (Fig. 1B,C), but no Paip2 homologs were found in Caenorhabditis elegans, S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, or plants. Nevertheless, PAM1- and PAM2-containing proteins have been found in Arabidopsis thaliana (Bravo et al. 2005). Surprisingly, the amino acid sequences of the Xenopus laevis and zebrafish putative Paip2 homologs are more similar to Paip2B (frog: 77% identical/88% similar to Paip2B vs. 57%/78% to Paip2A; zebrafish: 51% identical/68% similar to Paip2B vs. 48%/65% to Paip2A). In fact, these sequences appear to share an ancestor with human and mouse Paip2B (Fig. 1C). Salmon Paip2, however, seems to have evolved independently from the other sequences. The D. melanogaster genome contains the most distant putative Paip2 homolog with only 25% amino acid identity and 50% similarity with Paip2B, and 31% identity and 51% similarity with Paip2A (Fig. 1B,C). However, D. melanogaster Paip2, similar to its mammalian homologs, inhibits translation in vitro and cell growth when overexpressed in fly tissues (Roy et al. 2004).

The human Paip2A and Paip2B phylogenetic distribution (Fig. 1C) suggests that these two sequences diverged early during their evolution. While our results show that both homologs regulate PABP function on translation, other distinct functions for both proteins may yet be identified. Thus, considering these observations, it is reasonable to speculate that these two proteins evolved separately, either to serve different functions or, if their primary function is in translation, to be differentially regulated. Paip2A has been implicated in the regulation of mRNA stability through the binding to the 3′ untranslated region (Gouyon et al. 2003; Onesto et al. 2004).

Paip2A was initially described as a repressor of translation initiation (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b). However, the discovery that mammalian GSPT/eRF3 is a PABP-interacting protein that appears to stimulate translation of capped and polyadenylated mRNA by facilitating ribosome shunting from the 3′ to the 5′ end of the mRNA (Uchida et al. 2002) suggests that Paip2 proteins may also act as inhibitors of translation reinitiation. The C-terminal domain of GSPT/eRF3 interacts with eRF1 (eukaryotic releasing factor 1), and the N-terminal domain binds PABP, as do the Paip2 homologs via their C-terminal PAM2 domain. Thus, Paip2 proteins may also repress translation reinitiation by competing with GSPT/eRF3 for binding to PABP.

Northern and Western blots, together with quantitative RT-PCR data, show that both Paip2 mRNAs and proteins are present in a wide variety of tissues but at significantly different levels. Regarding mRNA levels, Paip2A is more abundant than is Paip2B, thus suggesting the presence of higher protein levels in cells and a possible predominant role for Paip2A in translational control, compared with Paip2B. Nevertheless, Paip2A and Paip2B are highly expressed in the testis compared with other tissues, raising the possibility that these proteins play an important role in spermatogenesis by modulating PABP activity. mRNA stability is crucial during spermatogenesis (Schafer et al. 1995; Steger et al. 1998), and high levels of PABP are present in mRNPs, suggesting its potential role in mRNA stability and translation. Moreover, a PABP isoform that is highly similar to PABP is expressed specifically in the testis, suggesting another possible target for Paip2-mediated regulation (Feral et al. 2001).

The longest Paip2B mRNA cloned from the brain is 6286 bp long, but the open reading frame comprises only 369 bp. Northern blots revealed the presence of three major Paip2B mRNA isoforms in most of the tissues examined, with each isoform present at different levels in different tissues (Fig. 7). In the brain the longest isoform predominates, while in the testis, where overall Paip2B mRNA is especially high, the shortest isoform is more abundant. These isoforms are most likely a consequence of the different polyadenylation signals present in the lengthy 3′ UTR that contains several canonical polyadenylation sites. However, the sizes of the two shorter mRNAs are compatible with two alternative polyadenylation signals (AGUAAC) at positions 684–689 and 1141–1146, respectively. The differential use of various polyadenylation sites may reflect the concentration of polyadenylation factors in different tissues and/or may be related to the way in which translation of these mRNAs is modulated (Edwalds-Gilbert et al. 1997), representing another way in which Paip2B protein levels are regulated.

Both Paip2B and Paip2A can be ubiquitinated. The conserved PABC domain that interacts with PAM2 in Paip1, Paip2A, and Paip2B is also found in a second family of proteins comprising HYD (for hyperplastic discs) in D. melanogaster, EDD in humans, and 100-kDa protein (rat100) in rats (Deo et al. 2001). In addition, all these proteins contain the HECT domain, which is characteristic of a family of proteins that function as E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases that target specific proteins for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (Callaghan et al. 1998; Hershko and Ciechanover 1998; Honda et al. 2002; Oughtred et al. 2002). We recently showed that Paip2 becomes ubiquitinated via its interaction with EDD through its PAM2/PABC domain (Yoshida et al. 2006). The degradation of Paip2 proteins by the ubiquitin/proteasome system constitutes the first evidence that these proteins are post-translationally regulated, thereby providing a mechanism for controlling their levels and, consequently, modulating PABP function and translation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Paip2B cDNA (clone KIAA1155) (Hirosawa et al. 1999) was kindly provided by Takahiro Nagase of Kazusa DNA Research Institute (Japan).

Sequence analysis

Amino acid sequences were aligned by using the CLUSTAL W program (Thompson et al. 1994) running on an NPS@ server (Combet et al. 2000). Matrix distances for the Kimura two-parameter model were then generated (Felsenstein 1993) and used to compute neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees. The robustness of each node was assessed by bootstrap resampling (1000 pseudoreplicates). Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted by using MEGA version 2.1 (Kumar et al. 1994). The GenBank accession numbers corresponding to the sequences used throughout the phylogenetic studies are AF317675 (human Paip2A), BF166492 (mouse Paip2A), BE372304 (mouse Paip2B), AAF54880 (D. melanogaster Paip2), BJ028919 (Xenopus laevis Paip2), AJ424615 (salmon Paip2), BQ131348 (zebrafish Paip2-1), and BI706223 (zebrafish2 Paip2-2).

GST pull-down assay

Purified GST fusion proteins (5 μg) encoding GST-Paip2B or GST-Paip2A were incubated for 15 min at 4°C with 5 μg of PABP-His in a total volume of 300 μL pull-down buffer (PDB; 20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5%[w/v] glycerol, 0.5% [w/v] NP-40). GST was used as a negative control. Each assay was then incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the beads washed four times with 500 μL of PDB. Proteins were eluted with 25 μL of 1× Laemmli sample buffer. The samples were boiled for 5 min, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue R-250.

Cell culture and transient transfection

293T, HeLa, COS-7, and NIH 3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO) in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. 293T cells at 70%–80% confluence were transiently transfected by using the Lipofectamine and Plus reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In the experiments that examined the effect of Paip2 on in vivo translation, cells were cotransfected with a fixed amount of plasmid pcDNA3-CAT-HCV IRES-Luc encoding the bicistronic CAT-HCV IRES-luciferase mRNA (Rivas-Estilla et al. 2002) along with increasing amounts of pcDNA3 plasmid (Invitrogen) encoding either HA-tagged Paip2B or HA-tagged Paip2A. The total amount of DNA was kept constant by the addition of empty pcDNA3 plasmid. Cells were harvested 24–36 h after transfection for further analysis.

Protein expression and purification

HMK-PABP-His (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a) and GST-HMK-PABP-His (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a; Roy et al. 2002) were expressed and purified as previously described. For purification of GST fusion proteins, Escherichia coli BL21 cells were transformed with the various pGEX6P constructs encoding GST-PABP fragments (RRM 1, 2, 3, 4, 1–2, 3–4. 2–3, C1, and C2), GST, and GST fusion proteins, lysed by sonication, and the fusion proteins were then purified as previously described (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a) using glutathione-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). HMK-Paip2B-His was expressed as a GST fusion protein, and the GST portion was cleaved on the column by using PreScission protease according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Purified proteins were dialyzed against the appropriate buffer or used directly in cleavage buffer.

Far-Western analysis

All experiments were performed as previously described (Khaleghpour et al. 1999). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C in hybridization buffer containing 32P-HMK-PABP-His or 32P-HMK-Paip2B-His as previously described (Blanar and Rutter 1992), washed four times with hybridization buffer, and exposed to X-ray film (Du Pont).

Paip2B-specific antibody and Western blotting

Two New Zealand White rabbits were immunized with 0.25–0.5 mg GST-Paip2B (residues 1–21) at 4-wk intervals. Crude serum was used for Western blotting at 1:1000 dilution. All antibodies were diluted in TBS-T (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) containing 5% nonfat milk. Membranes were washed three times with TBS-T and incubated with either anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) diluted 1:5000 in TBS-T for 30 min. After extensive washing with TBS-T, proteins were detected by using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and X-ray film (Du Pont). Other antibodies used for Western blot experiments were rabbit polyclonal antibodies anti-PABP (Imataka et al. 1998) and anti-eIF2α (FL-315, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Tissue and cell extract preparation and immunoprecipitation

Tissues were obtained from 16-wk-old Balb/c mice and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. Tissues were thawed on ice and homogenized in 3 mL of ice-cold buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, including Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Complete [Roche]) per g of tissue using a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and protein concentration was measured in the supernatant using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay. Equivalent amounts of protein (150 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE for Western blot and far-Western analyses. Cell extracts were prepared by using lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Complete [Roche]). After centrifugation to remove cell debris, the clarified supernatant (0.4–1.5 mg protein) was incubated with the appropriate antibody (mouse monoclonal anti-HAII [BABCO], rabbit polyclonal anti-Paip2A, or anti-Paip2B) and 20 μL Protein G–Sepharose slurry (50% v/v) for 1–3 h at 4°C. After three washes with 1 mL lysis buffer, proteins were eluted with 1× Laemmli sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for Western blot or far-Western analyses.

CAT protein and luciferase activity determination

Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed by using Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega). After removal of cell debris, equal amounts of total protein were used to measure CAT protein (CAT ELISA, Roche) and luciferase activity (Luciferase Assay System, Promega) in the lysates.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR

Mouse tissues were obtained from Balb/c male and female mice as described above. Total RNA from mouse tissues was extracted by using TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. To avoid genomic DNA contamination, RNA samples were treated with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega) and precipitated in the presence of 3 M LiCl and 20 mM EDTA. Human total RNA corresponds to FirstChoice Human Total RNA Survey Panel (Ambion). For determination of Paip2A and Paip2B mRNA expression, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed in a 20 μL reaction mixture also containing AMV Reverse Transcriptase and its corresponding buffer (Promega), the four dNTPs (BIOTOOLS), and gene specific primers for mouse/human Paip2A, Paip2B, or GAPDH (Invitrogen). The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min at 48°C, followed by enzyme inactivation for 5 min at 95°C. The LightCycler FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I system (Roche) was used for real-time PCR amplification using 1 μL of first-strand cDNA reaction as a template. The level of GAPDH mRNA in each sample was determined in order to normalize for differences of total RNA amount. The data were derived from at least three independent reverse-transcription reactions and real-time PCR performed in duplicate. Data analysis to determine relative Paip2A and Paip2B mRNA expression was performed according to the 2− ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Primers were designed to amplify fragments of ∼300 bp in the open reading frame of mouse and human Paip2A (330 bp), Paip2B (326 bp), and GAPDH (295 bp).

Northern blotting

Two Human Multiple Tissue Northern blot membranes (Clontech) were consecutively hybridized with 32P-labeled probes specific to Paip2B (open reading frame or 5′ untranslated regions), Paip2A (Acc I-Pst I fragment from the 3′ untranslated region) or actin (Clontech) according to manufacturer's instructions. After extensive washing, the membranes were exposed to BioMax MS film (Eastman Kodak).

In vitro translation

Capped poly(A)+ bicistronic CAT-HCV IRES-luc mRNA was translated in vitro in a Krebs-2 cell-free translation system (Svitkin et al. 1984) as previously described (Khaleghpour et al. 2001a, Khaleghpour et al. 2001b). Translation reactions (12.5 μL) contained 40 ng mRNA in the absence or presence of affinity-purified GST, GST-Paip2B, or GST-Paip2A. CAT expression was measured by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Roche). Luciferase expression was analyzed by using a luciferase assay kit (Promega) and a Lumat LB 9507 bioluminometer (Berthold).

Filter binding assay

Filter binding was performed as previously described (Khaleghpour et al. 2001b). Briefly, a radiolabeled A25 RNA was added to varying mixtures of His-PABP and GST, GST-Paip2A, or GST-Paip2B. Binding reactions were carried out for 30 min at room temperature. To determine the relative dissociation constants of PABP, the concentrations of RNA and GST-containing proteins were kept constant, and the concentration of PABP was varied. The radioactive RNA retained on filters was quantified by liquid scintillation counting. The value obtained at the highest PABP concentration in the presence of GST was designated “100% retention.”

Pulse-chase experiments

HEK 293T cells were transfected in 10-cm dishes, as described above, and were split up into 6-cm dishes at 24 h post-transfection. Cells were washed once with methionine-deficient medium, then incubated for 15 min in the same medium containing 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, and finally labeled in the same medium containing 0.1 mCi/mL [35S]methionine for 2 h. The cells were then washed once with normal growth medium containing 10 mM unlabeled methionine and chased for 5 h in the absence or the presence of 50 μM LLnL proteasome inhibitor (Sigma). For another set of experiments, cells were first labeled for 1 h in the absence or the presence of 10 μM MG132 proteasome inhibitor (Calbiochem) and then chased for 5 h under the same conditions, as described above. The cells were washed once with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer. Equal amounts of total protein were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA as described above. Immune complexes were washed extensively with lysis buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE (12% gel), dried, and exposed to X-ray film; alternatively, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, exposed to X-ray film, and then probed with anti-PABP or anti-HA antibodies, as indicated.

In vivo ubiquitination experiments

HEK 293 cells were cotransfected as described above with a plasmid encoding His6-ubiquitin (Treier et al. 1994) along with a plasmid encoding either HA-Paip2A or HA-Paip2B, or the same plasmid containing no insert. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were either mock-treated or treated with 50 μM LLnL. Cells were lysed in guanidine-HCl denaturing buffer, and His6-tagged proteins were purified by using the TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech) as described previously (Treier et al. 1994). Bound proteins were eluted from the resin with 25 μL of 1× Laemmli sample buffer and resolved by SDS-PAGE (12% gel). HA-Paip2A and HA-Paip2B were visualized by Western blotting with anti-HA, while untagged or endogenous Paip2A and Paip2B were visualized by using antibodies specific to Paip2A or Paip2B.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yuri Svitkin, Maria Ferraiuolo, and Avak Kahvejian for providing Krebs-2 cell extract, mouse tissues extracts, and GST-PABP fragments, respectively. We thank Hiroaki Imataka and Guylaine Roy for helpful discussions. We also thank Colin Lister for excellent technical assistance and Mauro Costa-Mattioli for helping with sequence alignments and the phylogenetic tree. This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and National Institutes of Health (NIH, ROI GM66157). N.S. is a CIHR distinguished scientist and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Scholar. A.B. is a recipient of a fellowship from the Fond pour la Formation de Chercheurs et l'Aide à la Recherche (FCAR). J.J.B. was a recipient of postdoctoral fellowships from the Ministerio de Educación y Deporte (Spain).

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.106506.

REFERENCES

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanar M.A., Rutter W.J. Interaction cloning: Identification of a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that interacts with c-Fos. Science. 1992;256:1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.1589769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo J., Aguilar-Henonin L., Olmedo G., Guzman P. Four distinct classes of proteins as interaction partners of the PABC domain of Arabidopsis thaliana Poly(A)-binding proteins. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2005;272:651–665. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan M.J., Russell A.J., Woollatt E., Sutherland G.R., Sutherland R.L., Watts C.K. Identification of a human HECT family protein with homology to the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene hyperplastic discs. Oncogene. 1998;17:3479–3491. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combet C., Blanchet C., Geourjon C., Deleage G. NPS@: Network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon I., Raff M. Size control in animal development. Cell. 1999;96:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A.W., Haghighat A., Yu A.T., Sonenberg N. Interaction of polyadenylate-binding protein with the eIF4G homologue PAIP enhances translation. Nature. 1998;392:520–523. doi: 10.1038/33198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deo R.C., Sonenberg N., Burley S.K. X-ray structure of the human hyperplastic discs protein: An ortholog of the C-terminal domain of poly(A)-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:4414–4419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071552198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwalds-Gilbert G., Veraldi K.L., Milcarek C. Alternative poly(A) site selection in complex transcription units: means to an end? Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2547–2561. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: phylogeny inference package. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Feral C., Guellaen G., Pawlak A. Human testis expresses a specific poly(A)-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1872–1883. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras A.C., Raught B., Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: Effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouyon F., Onesto C., Dalet V., Pages G., Leturque A., Brot-Laroche E. Fructose modulates GLUT5 mRNA stability in differentiated Caco-2 cells: Role of cAMP-signalling pathway and PABP (polyadenylated-binding protein)-interacting protein (Paip) 2. Biochem. J. 2003;375:167–174. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey J.W.B., Merrick W.C. In: In Translational control of gene expression. Sonenberg N., et al., editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2000. pp. 33–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirosawa M., Nagase T., Ishikawa K., Kikuno R., Nomura N., Ohara O. Characterization of cDNA clones selected by the GeneMark analysis from size-fractionated cDNA libraries from human brain. DNA Res. 1999;6:329–336. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.5.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y., Tojo M., Matsuzaki K., Anan T., Matsumoto M., Ando M., Saya H., Nakao M. Cooperation of HECT-domain ubiquitin ligase hHYD and DNA topoisomerase II-binding protein for DNA damage response. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3599–3605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imataka H., Gradi A., Sonenberg N. A newly identified N-terminal amino acid sequence of human eIF4G binds poly(A)-binding protein and functions in poly(A)-dependent translation. EMBO J. 1998;17:7480–7489. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahvejian A., Svitkin Y.V., Sukarieh R., M'Boutchou M.N., Sonenberg N. Mammalian poly(A)-binding protein is a eukaryotic translation initiation factor, which acts via multiple mechanisms. Genes & Dev. 2005;19:104–113. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghpour K., Pyronnet S., Gingras A.C., Sonenberg N. Translational homeostasis: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E control of 4E-binding protein 1 and p70 S6 kinase activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4302–4310. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghpour K., Kahvejian A., De Crescenzo G., Roy G., Svitkin Y.V., Imataka H., O'Connor-McCourt M., Sonenberg N. Dual interactions of the translational repressor Paip2 with poly(A) binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001a;21:5200–5213. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5200-5213.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleghpour K., Svitkin Y.V., Craig A.W., DeMaria C.T., Deo R.C., Burley S.K., Sonenberg N. Translational repression by a novel partner of human poly(A) binding protein, Paip2. Mol. Cell. 2001b;7:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Tamura K., Nei M. MEGA: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software for microcomputers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1994;10:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔC(T) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews M.B., Sonenberg N., Hershey J.W.B. Origins and principles of translational control. In: Sonenberg N., et al., editors. Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2000. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Onesto C., Berra E., Grepin R., Pages G. Poly(A)-binding protein–interacting protein 2, a strong regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:34217–34226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oughtred R., Bedard N., Adegoke O.A., Morales C.R., Trasler J., Rajapurohitam V., Wing S.S. Characterization of rat100, a 300-kilodalton ubiquitin-protein ligase induced in germ cells of the rat testis and similar to the Drosophila hyperplastic discs gene. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3740–3747. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova T.V., Shatsky I.N., Fletcher S.P., Jackson R.J., Hellen C.U. A prokaryotic-like mode of cytoplasmic eukaryotic ribosome binding to the initiation codon during internal translation initiation of hepatitis C and classical swine fever virus RNAs. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:67–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Estilla A.M., Svitkin Y., Lopez Lastra M., Hatzoglou M., Sherker A., Koromilas A.E. PKR-dependent mechanisms of gene expression from a subgenomic hepatitis C virus clone. J. Virol. 2002;76:10637–10653. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10637-10653.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy G., De Crescenzo G., Khaleghpour K., Kahvejian A., O'Connor-McCourt M., Sonenberg N. Paip1 interacts with poly(A) binding protein through two independent binding motifs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:3769–3782. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3769-3782.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy G., Miron M., Khaleghpour K., Lasko P., Sonenberg N. The Drosophila poly(A) binding protein-interacting protein, dPaip2, is a novel effector of cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1143–1154. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1143-1154.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs A.B. Physical and functional interactions between the mRNA cap structure and the poly(A) tail. In: Sonenberg N., et al., editors. Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2000. pp. 447–465. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs A.B., Davis R.W., Kornberg R.D. A single domain of yeast poly(A)-binding protein is necessary and sufficient for RNA binding and cell viability. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:3268–3276. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.9.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer M., Nayernia K., Engel W., Schafer U. Translational control in spermatogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1995;172:344–352. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.8049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger K., Klonisch T., Gavenis K., Drabent B., Doenecke D., Bergmann M. Expression of mRNA and protein of nucleoproteins during human spermiogenesis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1998;4:939–945. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.10.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkin Y.V., Lyapustin V.N., Lashkevich V.A., Agol V.I. Differences between translation products of tick-borne encephalitis virus RNA in cell-free systems from Krebs-2 cells and rabbit reticulocytes: Involvement of membranes in the processing of nascent precursors of flavivirus structural proteins. Virology. 1984;135:536–541. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svitkin Y.V., Pause A., Haghighat A., Pyronnet S., Witherell G., Belsham G.J., Sonenberg N. The requirement for eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (elF4A) in translation is in direct proportion to the degree of mRNA 5′ secondary structure. RNA. 2001;7:382–394. doi: 10.1017/s135583820100108x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun S.Z., Jr., Sachs A.B. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996;15:7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treier M., Staszewski L.M., Bohmann D. Ubiquitin-dependent c-Jun degradation in vivo is mediated by the delta domain. Cell. 1994;78:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N., Hoshino S., Imataka H., Sonenberg N., Katada T. A novel role of the mammalian GSPT/eRF3 associating with poly(A)-binding protein in Cap/Poly(A)-dependent translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:50286–50292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M., Yoshida K., Kozlov G., Lim N.S., De Crescenzo G., Pang Z., Berlanga J.J., Kahvejian A., Gehring K., Wing S.S., et al. Poly(A) binding protein (PABP) homeostasis is mediated by the stability of its inhibitor, Paip2. EMBO J. 2006;25:1934–1944. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]