Abstract

By use of a murine model for Buruli ulcer, Mycobacterium ulcerans was found to be susceptible to rifampin, with the MIC being 0.5 to 1 μg/ml. Three mutants were isolated after rifampin monotherapy. Two were resistant to rifampin at 8 μg/ml, and one was resistant to rifampin at 32 μg/ml. The mutants harbored Ser416Phe mutations and His420Tyr mutations in the rpoB gene, and these mutations have also been found to be responsible for rifampin resistance in the leprosy and tubercle bacilli. The results indicate that while rifampin may be active against M. ulcerans, it should never be used as monotherapy in humans.

Buruli ulcer is the third most important mycobacterial disease after tuberculosis and leprosy in humid tropical countries in West Africa. The disease is due to Mycobacterium ulcerans, the only mycobacterium known to produce a dermonecrotic toxin (6, 7). The infection starts with a painless nodule or papule which spreads over the surrounding tissue. Ischemic and necrotized tissues disappear and are replaced by a centrifugal ulceration over the limb. Nowadays, surgery, the only effective treatment, consists of excision of as much of the lesion as possible, often followed by a skin transplant. Mutilating and disabling aftereffects linked to retractile fibrosis, as well as frequent relapses, occur (1). Moreover, bone and articulations may be affected by the disease, and this further complicates therapy (13).

Many studies have proposed the use of antibiotic therapy. Unfortunately, the results have been disappointing and there is no well-defined protocol with curative activity against infections in humans (3). However, the existence of such a protocol would be of great importance so that patients could be treated as soon as the first clinical signs, such as edema and bone joint disease, appear. This would limit the spread of ulceration and lead to sterilization. Consequently, less aggressive surgery would be required and fewer aftereffects and relapses would be observed.

Experimental chemotherapy has been carried out with infected mice, and studies have shown that rifampin is active (4, 8, 20) in vivo. In this study we report on the risk of emergence of rifampin-resistant strains in experimentally infected mice treated with rifampin alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains and isolation of rifampin-resistant mutants.

M. ulcerans (strain 01G897) was originally isolated from a skin biopsy specimen of a human patient from French Guyana (5) and was passaged on Löwenstein-Jensen medium at 30°C (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes la Coquette, France). In the first experiment, 30 μl of a suspension containing 5 × 104 cells was injected subcutaneously into a footpad of each of 120 BALB/c mice (age, 5 weeks; Iffa Credo, Saint Germain sur l'Arbresle, France). After inoculation, the initial suspension was frozen at −80°C. Five weeks later, all the mice showed inflammatory lesions. The mice were then dispatched at random into two groups.

The mice in group 1 (50 mice) were not treated and was used as the control group. Five mice were killed every week, and the number of bacilli present in infected tissues was counted. The mice in group 2 (70 mice) were treated with rifampin (10 mg/kg of body weight 5 days a week). Five mice were killed every 2 weeks for 3 months, and the number of bacilli present in infected tissues was counted. At the end of the 90-day treatment, 30 mice from group 2 were kept for a further 3 months for clinical observations to detect the emergence of any possible resistant strains.

In the second experiment, the initial suspension (containing 1.7 × 106 bacilli per ml) was inoculated on Löwenstein-Jensen medium with or without rifampin at 30 μg/ml, as described for the proportion method (2). This suspension was also injected subcutaneously into a footpad of each of 40 BALB/c mice. The mice were treated with rifampin for 3 months by the same method used in the first experiment.

Enumeration of M. ulcerans in infected tissues.

The tissue specimens from five mice were weighed, minced with disposable scalpels in a petri dish, and ground with a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer (size 22; Kimble/Kontes, Vineland, N.J.) in 0.15 M NaCl to obtain a 10-fold dilution. Smears of suspensions were stained by the Ziehl-Neelsen procedure. The suspension was decontaminated with an equal volume of N-acetyl-l-cysteine sodium hydroxide (2%) as described previously (11), and cultures were obtained by inoculating 0.2 ml onto two Löwenstein-Jensen slants (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur). After Ziehl-Neelsen staining, the acid-fast bacilli were counted by the method of Shepard and Rae (19).

Study of efficiency of rifampin.

After proliferation by the standard method (22), the activity of rifampin was tested against four strains of M. ulcerans: wild-type strain 897 and three rifampin-resistant strains (strains R1, R2, and R3) from mice that had relapses after 90 days of treatment. The precise level of resistance to rifampin was determined by measuring the MIC in liquid medium by the method described by Rastogi et al. (18). In our experiments, the MIC corresponded to the lowest amount of antibiotic that inhibited 99% of the growth of M. ulcerans.

Proof of infectious activities of resistant strains and demonstration of acquired resistance.

After culture on Löwenstein-Jensen medium, bacilli of strains 897, R1, and R2 were suspended in saline, centrifuged, and resuspended in saline to obtain 5 × 104 bacilli in 30 μl. Three groups of 20 BALB/c mice each were constituted: the wild-type strain was injected into the mice in group 1, while the mice in groups 2 and 3 received bacilli from strains R1 and R2, respectively. Approximately 4 weeks later, edema appeared on the legs of all the mice. Ten mice from each group were treated with rifampin for 3 months, and clinical observations were made each week.

Sequencing of the rpoB gene.

After 6 weeks of culture on Löwenstein-Jensen medium, the colonies were harvested and a suspension of the bacteria was made in 200 μl of sterile distilled water. The bacteria were heated at 100°C for 30 min and then lysed by five cycles of boiling and freezing (25) before a second treatment at 100°C for 10 min. A fragment of 326 bp of rpoB was amplified by PCR with M. ulcerans-specific primers MulrpoB-R (5′-TGCGCACGGTGGGTGAGC-3′) and MulrpoB-F (5′-GACGTGCACCCGTCGCACT-3′) (12). The reaction was carried out in a final volume of 50 μl containing 5 μl of DNA, 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer [170 mM (NH4)2SO4, 600 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 20 mM MgCl2, 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol], 5 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide, 5 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (5 mM each), 5 μl of primers (2 μM), 25 μl of distilled water, and 2 U of Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL). The amplification was performed by 45 cycles of 1 min at 92°C, 2 min at 59°C, and 2 min at 72°C, with a final step at 72°C for 10 min. After purification the amplified fragments were sequenced with an ABI 377 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems), BigDye terminators, and primers MulrpoB-R and MulrpoB-F.

RESULTS

Effect of rifampin on experimentally infected mice.

At the beginning of the treatment, which corresponds to 5 weeks after inoculation, the number of visible acid-fast bacilli counted in infected tissues was 3.24 × 107 per g of tissue. Among these bacilli, 4.1 × 106 organisms per g of tissue were viable. At this stage the feet of the mice displayed extensive edema that had spread over the leg. In the control group, the number of organisms increased until the 9th week after inoculation, with 108 viable bacilli per g of tissue being attained. In the group treated with rifampin, the number of bacilli increased for the first 15 days (7th week after inoculation), reaching a maximum level of 5.6 × 106 viable bacilli per g of tissue. Subsequently, the number of viable organisms decreased; and from weeks 12 to 16, the end of the treatment, no viable bacilli were found. Inflammatory reactions disappeared, although some redness remained on the footpads.

After 90 days of treatment with rifampin, 30 mice were alive and were kept for observation. At 6 and 7 weeks after the end of the treatment, relapses occurred in two mice, which developed a large inflammation of the footpads. Tissue samples were then taken from these lesions, and culture of the tissue led to the isolation of M. ulcerans. No relapses occurred in the 28 mice surviving at the end of these 3 months.

In the second experiment, 40 mice were kept alive after 3 months of treatment. During the 3 months after the end of treatment one mouse had a relapse, and M. ulcerans was isolated from the footpad tissues.

Rifampin sensitivities of strains.

M. ulcerans 897 was inhibited by 1 μg of rifampin per ml, whereas no inhibition was observed for the three strains isolated from the mice in which relapses occurred in the two experiments. The MIC, determined by a dilution method, was 0.5 μg/ml for the wild-type strain, whereas the MICs were 8 μg/ml for strains R1 and R2 and 32 μg/ml for strain R3; these correspond to >8-fold and > 16-fold increases, respectively.

Detection of rifampin-resistant mutants in a bacterial inoculum.

No rifampin-resistant mutants were isolated from the suspension from which samples were taken for inoculation into the mice, indicating that the number of spontaneously resistant mutants in the initial inoculum was below the limit of detection of this method.

Comparison of pathological effects of strains R1 and R2 and the wild-type strain.

Whether the strain was sensitive or resistant to rifampin, the clinical evolutions of the infections were similar in the untreated mice. Five weeks after inoculation, all of the mice had large areas of inflammatory edema over their feet. There were no ulcerations. Nine weeks after inoculation, the whole leg of each mouse showed major edema and extensive lesions. Between the 9th and the 12th weeks, all of the animals died of secondary infections.

Mice infected with M. ulcerans 897 and treated with rifampin showed inflammatory lesions that decreased after 30 days of treatment but an edema that persisted on the footpads. No inflammation was observed 60 days after the beginning of the treatment (12 weeks after inoculation); only redness of the footpad was observed.

Similar clinical observations were made for animals (20 mice) inoculated with strains resistant to rifampin. After 30 days of treatment, 15 of 20 mice showed major edema of the leg, similar to that observed in the untreated mice. Five mice had an edema of the footpad which decreased.

After 90 days of treatment, 15 mice had died. The MICs for the bacilli isolated from infected tissues were the same as those for strains Rl and R2, that is, 8 μg/ml. Among the five surviving mice, one mouse had edema on the whole leg. M. ulcerans was isolated from tissues taken from this mouse, and the MIC for that isolate was the same as that for strains R1 and R2. No bacilli were isolated from the other four mice.

With respect to mutant R3, a preliminary study showed that the strain is pathogenic for mice and that the rifampin treatment was inefficient.

Sequencing of rpoB of M. ulcerans.

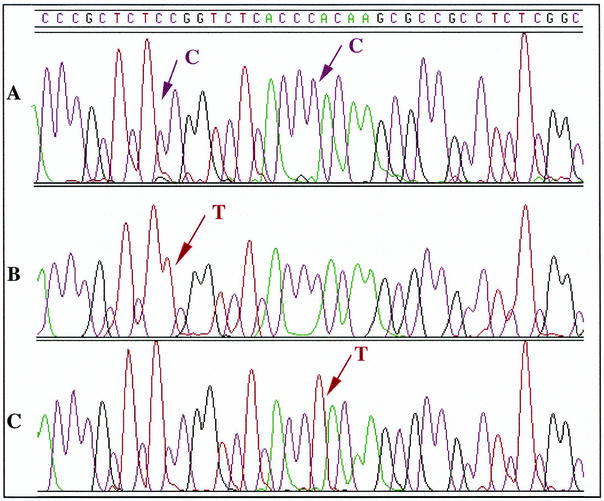

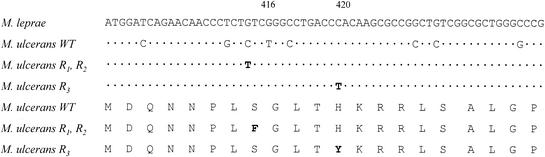

The 326-bp amplicon generated by PCR was sequenced. The sequence of this region showed 90.2% identity with the M. leprae sequence (9). Figures 1 and 2 show the alignment of a 62-bp fragment, corresponding to the rifampin resistance-determining region, from both organisms. When the sequence of the same region of the rpoB gene from resistant strains R1 and R2 was determined, a missense mutation was found in codon 416 (TCC→TTC), resulting in the replacement of a serine by a phenylalanine (Fig. 1 and 2). The same point mutation was observed in both strain R1 and strain R2. For strain R3 a different missense mutation was found in codon 420 (CAC→TAC), resulting in the replacement of a histidine by a tyrosine (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the DNA sequence chromatograms for the part of the rpoB region containing the resistance-conferring mutations. The arrows in the chromatograms indicate the positions of nucleotide changes. (A) Wild-type strain; (B) mutants R1 and R2, in which the codon TCC is replaced by TTC; (C) mutant R3, in which the codon CAC is replaced by TAC.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the rifampin resistance-determining regions of the rpoB genes from M. ulcerans and M. leprae. Only the nucleotides of wild-type (WT) or resistant (mutant R1, R2, and R3) M. ulcerans strains which differ from those in M. leprae are shown; identical nucleotides are denoted by periods. Note the amino acid changes Ser to Phe at position 416 and His to Tyr at position 420.

DISCUSSION

Ansamycins (rifamycin and rifampin) were discovered in 1967 and have been used for therapy since 1970. Their efficacies as treatments for tuberculosis have been proved. In 1981, rifampin was included as part of the treatment regimen for leprosy and became one of the main drugs used in multidrug therapy (26). Following an epidemic of Buruli ulcer in Uganda in the 1960s (23), the activity of rifampin as a treatment for that disease was tested in mice experimentally infected with M. ulcerans (8, 21). The observations from our study, which was prompted by the epidemic occurring in West Africa (1), mirror what Dega et al. (4) observed. The efficiency of the treatment has been confirmed in studies with experimentally infected mice. Rifampin had a high level of activity when it was used to treat mice experimentally infected with 106 bacilli. By use of such an inoculum, the mice showed large edemas of the footpads after 5 weeks, when treatment with rifampin began. Thus, we concluded that, at the beginning of the appearance of ulcerative lesions, the infection in mice is very similar to the one observed in humans, when people become concerned and obtain medical advice. No viable bacilli were found 4 weeks after the start of treatment, and only a slight persisting inflammation was observed in the tissues until the end of the experiment. This was probably a sequella of the extensive inflammatory lesions seen at the beginning of the infection.

It has been known since 1947 (27) that monotherapy with streptomycin and subsequently with other antituberculosis drugs results in the occurrence of drug-resistant mutants. Rifampin is no exception, and many studies have shown that resistant strains can be selected after tuberculosis or leprosy is treated with rifampin alone (17).

After 3 months of experimental treatment of 30 infected mice with rifampin, followed by another 3 months of clinical observation, we isolated two strains (strains R1 and R2) for which the rifampin MIC was increased more than eightfold. The probability of a relapse by use of such a protocol was 6.7%. Among the 107 to 108 M. ulcerans bacilli inoculated, at least 1 bacillus was resistant to rifampin. This rate is close to those observed for M. tuberculosis and M. leprae. In early lesions in the edematous form or in small ulcer active lesions there can be 107 to 108 bacilli/g of tissue (K. Asiedu, B. Carbonnelle, J. Grosset, and M. H. Wansbrough-Jones, unpublished data). This indicates that such mutants can be found in these lesions and that the resistant bacilli could be selected by the use of rifampin alone.

The mechanism of action of rifampin was first studied in Escherichia coli (16) and was confirmed in other species. Rifampin targets the β subunit of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, encoded by the rpoB gene (14), and resistance is due to missense mutations that occur in a highly conserved region of the gene. This phenomenon has been observed in M. tuberculosis, M. leprae, and other pathogenic mycobacteria (24). The comparative study of the rifampin resistance-determining region amplified from wild-type strain 897 and resistant strains R1 and R2 has shown that a point mutation is present in both R1 and R2. Serine 416 is thus replaced by phenylalanine, a voluminous and more hydrophobic amino acid. In strain R3, histidine is replaced by tyrosine. These changes have also been described in rifampin-resistant mutants of M. leprae and M. tuberculosis. Because of these substitutions the antibiotic can no longer bind to its target (9).

In M. tuberculosis, depending on the position of the mutation and the nature of the substituted amino acid, wide variations in the MIC are found (15). For strains R1 and R2, the MIC has increased to 8 μg/ml, which is a moderate level of resistance, whereas for strain R3 the MIC was 32 μg/ml, which corresponds to a high level of resistance. This modification did not affect the pathological effects of the resistant strains compared to that of the wild-type strain but led to clinical inefficacy, since 80% of the mice inoculated with strains R1 and R2 died, even with 90 days of treatment with rifampin. Modifications other than rifampin sensitivity were not observed in strains R1 and R2. Their physiological properties were the same as those of wild-type strain 897, and no other changes in their behaviors were observed, which is unlike the situation for certain resistant strains of E. coli (10).

In conclusion, the use of rifampin monotherapy of mice infected with M. ulcerans led to the isolation of resistant strains after 3 months of treatment. This result confirms the necessity of using a combination of different antibiotics for the treatment of Buruli ulcer to avoid the emergence of resistant strains in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Denizot and V. Moreau-Lherbette for technical assistance. We are also grateful for a predoctoral fellowship from l'Association Française Raoul Follereau (to L.M.).

This work was supported by a grant from the Raoul Follereau Association.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asiedu, K., R. Sherpbier, and M. C. Raviglione. 2000. Buruli ulcer Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. WHO Global Buruli Ulcer Initiative. Report 2000. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 2.Canetti, G., N. Rist, and J. Grosset. 1963. Mesure de la sensibilité du bacille tuberculeux par la méthode des proportions. Méthodologie, critères de résistance, résultats, interprétations. Rev. Tuberc. Pneumol. 27:217-272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darie, H., S. Djakeaux, and A. Cautoclaud. 1994. Therapeutic approach in Mycobacterium ulcerans infections. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 87:19-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dega, H., J. Robert, P. Bonnafous, V. Jarlier, and J. Grosset. 2000. Activities of several antimicrobials against Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2367-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Gentile, P. L., C. Mahaza, F. Rolland, B. Carbonnelle, J. L. Verret, and D. Chabasse. 1992. Cutaneous ulcer from Mycobacterium ulcerans. Apropos of 1 case in French Guyana. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 85:212-214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George, K. M., L. P. Barker, D. M. Welty, and P. L. Small. 1998. Partial purification and characterization of biological effects of a lipid toxin produced by Mycobacterium ulcerans. Infect. Immun. 66:587-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George, K. M., D. Chatterjee, G. Gunawardana, D. Welty, J. Hayman, R. Lee, and P. L. Small. 1999. Mycolactone: a polyketide toxin from Mycobacterium ulcerans required for virulence. Science 283:854-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Havel, A., and S. R. Pattyn. 1975. Activity of rifampicin on Mycobacterium ulcerans. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 55:105-108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honoré, N., and S. T. Cole. 1993. Molecular basis of rifampin resistance in Mycobacterium leprae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:414-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin, D. J., and C. A. Gross. 1989. Characterization of the pleiotropic phenotypes of rifampin-resistant rpoB mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:5229-5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent, P. T., and G. P. Kubica. 1985. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Ga.

- 12.Kim, B. J., S. H. Lee, M. A. Lyu, S. J. Kim, G. H. Bai, G. T. Chae, E. C. Kim, C. Y. Cha, and Y. H. Kook. 1999. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB). J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1714-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagarrigue, V., F. Portaels, W. M. Meyers, and J. Aguiar. 2000. Buruli ulcer: risk of bone involvement! Apropos of 33 cases observed in Benin. Med. Trop. 60:262-266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller, L. P., J. T. Crawford, and T. M. Shinnick. 1994. The rpoB gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:805-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohno, H., H. Koga, S. Kohno, T. Tashiro, and K. Hara. 1996. Relationship between rifampin MICs for and rpoB mutations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1053-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ovchinnikov, Y. A., G. S. Monastyrskaya, V. V. Gubanov, S. O. Guryev, O. Chertov, N. N. Modyanov, V. A. Grinkevich, I. A. Makarova, T. V. Marchenko, I. N. Polovnikova, V. M. Lipkin, and E. D. Sverdlov. 1981. The primary structure of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Nucleotide sequence of the rpoB gene and amino-acid sequence of the beta-subunit. Eur. J. Biochem. 116:621-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pablos-Mendez, A., M. C. Raviglione, A. Laszlo, N. Binkin, H. L. Rieder, F. Bustreo, D. L. Cohn, C. S. Lambregts-van Weezenbeek, S. J. Kim, P. Chaulet, P. Nunn, et al. 1998. Global surveillance for antituberculosis-drug resistance, 1994-1997. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:1641-1649. (Erratum, 339:139.) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Rastogi, N., R. M. Bauriaud, A. Bourgoin, B. Carbonnelle, C. Chippaux, M. J. Gevaudan, K. S. Goh, D. Moinard, and P. Roos. 1995. French multicenter study involving eight test sites for radiometric determination of activities of 10 antimicrobial agents against Mycobacterium avium complex. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:638-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepard, C. C., and D. H. M. Rae. 1968. A method for counting acid fast bacteria. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobacter. 36:78-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanford, J. L., and I. Phillips. 1972. Rifampicin in experimental Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 5:39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stannford, J. L., and R. C. Paul. 1973. A preliminary report on some studies of environmental mycobacteria. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 53:389-393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarrand, J. J., and D. H. Groschel. 1985. Evaluation of the BACTEC radiometric method for detection of 1% resistant populations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 21:941-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uganda Buruli Group. 1971. Epidemiology of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection at Kinyara, Uganda. Trans. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:763-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams, D. L., C. Waguespack, K. Eisenach, J. T. Crawford, F. Portaels, M. Salfinger, C. M. Nolan, C. Abe, V. Sticht-Groh, and T. P. Gillis. 1994. Characterization of rifampin resistance in pathogenic mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2380-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woods, S. A., and S. T. Cole. 1989. A rapid method for the detection of potentially viable Mycobacterium leprae in human biopsies: a novel applica-tion of PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 53:305-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. 1982. Chemotherapy of leprosy for control programmes. W. H. O. Tech. Rep. Ser. 675:1-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youmans, G. P., and A. G. Karlson. 1947. Streptomycin sensitivity of tubercle bacilli. Studies of recently isolated tubercle bacilli and development of resistance to streptomycin in vivo. Annu. Rev. Tuberc. 55:529-536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]