Abstract

Gatifloxacin (Bristol-Myers Squibb) and moxifloxacin (Bayer) are new methoxyfluoroquinolones with broad-spectrum activity against aerobic and anaerobic pathogens of the respiratory tract. In this investigation, we analyzed the bactericidal activity in serum over time of these antimicrobials against three aerobic (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Staphylococcus aureus) and four anaerobic (Peptostreptococcus micros, Peptostreptococcus magnus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Prevotella melaninogenica) bacteria associated with respiratory tract infections. Serum samples were obtained from 11 healthy male subjects following a single 400-mg oral dose of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin. These samples were collected prior to and at 2, 6, 12, and 24 h after the dose of each drug. Gatifloxacin exhibited bactericidal activity for a median of 12 h against Streptococcus pneumoniae (MIC = 0.5 μg/ml), Peptostreptococcus micros (MIC = 0.25 μg/ml), and F. nucleatum (MIC = 0.5 μg/ml) and 24 h against H. influenzae (MIC = 0.03 μg/ml), Staphylococcus aureus (MIC = 0.125 μg/ml), Peptostreptococcus magnus (MIC = 0.125 μg/ml), and Prevotella melaninogenica (MIC = 0.5 μg/ml). Moxifloxacin exhibited bactericidal activity for a median of 24 h against Streptococcus pneumoniae (MIC = 0.125 μg/ml), H. influenzae (MIC = 0.015 μg/ml), Staphylococcus aureus (MIC = 0.06 μg/ml), F. nucleatum (MIC = 0.5 μg/ml), Prevotella melaninogenica (MIC =0.5 μg/ml), Peptostreptococcus magnus (MIC = 0.125 μg/ml), and Peptostreptococcus micros (MIC = 0.25 μg/ml). The results from this pharmacodynamic study suggest that these fluoroquinolones would have prolonged killing activity against these organisms in vivo and may have clinical utility in the treatment of mixed aerobic-anaerobic respiratory tract infections.

Gatifloxacin (Bristol-Myers Squibb) and moxifloxacin (Bayer) are new 8-methoxyfluoroquinolones with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity which includes anaerobic bacteria (29). Both compounds have comparable in vitro activity against common aerobic and anaerobic respiratory pathogens (3). Moreover, they exhibit similar serum pharmacokinetics and penetration into respiratory tissues (9, 24). The ability of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin to eradicate aerobic respiratory pathogens, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, has been well documented in pharmacodynamic models and clinical trials (9, 24). Their effectiveness in the treatment of anaerobic infections is unknown.

In contrast to studies with aerobic bacteria, where concentration-dependent killing has been observed, concentration-independent killing was discovered against Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron with various fluoroquinolones in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model (27). This model further discovered that resistant strains of Bacteroides fragilis emerged when the area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC24)-to-MIC ratio was less than 40 (26). In time-kill assays, maximal bactericidal activity against various anaerobes (B. fragilis, B. thetaiotaomicron, Peptostreptococcus magnus, and Clostridium perfringens) was observed at twice the MIC with levofloxacin (25). These in vitro investigations suggest that relatively low, prolonged concentrations of newer fluoroquinolones have the ability to eradicate susceptible anaerobic organisms.

In this study, we determined the bactericidal activity in serum over time of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin against common aerobic and anaerobic bacteria associated with community-acquired respiratory infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Eleven healthy male volunteers participated in this investigation. Each gave written informed consent that was approved by the University Committee on Research in Human Subjects at Michigan State University. None of these subjects had a history of chronic disease or were receiving medications. These volunteers had a mean age of 36 years (range, 27 to 54 years) and a mean weight of 86 kg (range, 62 to 114 kg). All were within 20% of their ideal body weight.

Drug administration.

Each subject received a single 400-mg oral dose of gatifloxacin (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, N.J.) and moxifloxacin (Bayer Corporation, West Haven, Conn.). Study subjects initially received gatifloxacin, and after a 1-week washout period, each volunteer received a dose of moxifloxacin. The study antibiotics were taken on an empty stomach following a 12-h fast. Food intake was allowed 2 h after receiving the dose of antibiotic.

Serum samples.

Venous blood samples were obtained immediately before (time zero, control) and at 2, 6, 12, and 24 h after the dose of each drug. Following centrifugation, serum samples were aliquotted and stored at −70°C until the time of analysis. Concentration in serums of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin were measured at each time period by a validated high-performance liquid chromatographic method (20, 34).

Bacterial strains.

The inhibitory activities of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin were determined by microdilution (aerobes) and agar dilution (anaerobes) methods as recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (22, 23).

For testing of aerobic organisms, cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth with the appropriate supplements (3% lysed horse blood, Haemophilus test media) was utilized. One representative clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae was tested. The control organisms tested included ATCC reference strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae (ATCC 49619), H. influenzae (ATCC 49247), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213). Susceptibility testing of anaerobic organisms was performed with Brucella agar supplemented with hemin, vitamin K, and 5% laked sheep blood (30). The respiratory anaerobes tested included recent clinical isolates of Peptostreptococcus magnus (Finegoldia magna), Peptostreptococcus micros, Prevotella melaninogenica, and Fusobacterium nucleatum. An inoculum of 105 CFU per well was incubated for 24 h for aerobic bacteria and 48 h for anaerobes. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that prevented visible growth.

Bactericidal titers in serum.

Iinhibitory and bactericidal titers in serum were determined according to NCCLS standards (21). Each determination was performed in duplicate.

Wells with no visible growth and the first growth well were subcultured to supplemented Mueller-Hinton agar (aerobes) or Brucella agar (anaerobes) plates that were incubated for 2 (aerobes) or 3 (anaerobes) days prior to counting colonies.

Both aerobic and anaerobic isolates were tested against serum collected at each time period for all subjects. The bactericidal titer in serum endpoint was determined as the highest dilution of serum yielding 99.9% killing. The median and geometric mean bactericidal titers at each time period were calculated and plotted.

RESULTS

Each of the 11 subjects received the study antibiotics according to the protocol, and no adverse experiences were observed or reported.

The MICs of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin for the study organisms are presented in Table 1. The potency of these two antibiotics was found to be similar for both the aerobic and anaerobic bacteria that were studied. All isolates had MICs of ≤0.5 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

MICs of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin against aerobic and anaerobic study isolates

| Organism | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Gatifloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| Aerobes | ||

| S. pneumoniae | 0.5 | 0.125 |

| S. aureus | 0.125 | 0.06 |

| H. influenzae | 0.03 | 0.015 |

| Anaerobes | ||

| F. nucleatum | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| P. melaninogenica | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| P. magnus | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| P. micros | 0.25 | 0.25 |

The mean concentrations of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin in serum in these subjects were similar, with the exception of the levels at 2 h after the dose (Table 2). Gatifloxacin exhibited higher concentrations in serum at this sampling time (3.20 versus 2.45 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

Single-dose (400 mg) concentrations of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin in serum

| Time (h) | Mean concn (μg/ml) in serum ± SD

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Gatifloxacin | Moxifloxacin | |

| 2 | 3.20 ± 0.80 | 2.45 ± 0.57 |

| 6 | 1.83 ± 0.39 | 1.72 ± 0.41 |

| 12 | 1.03 ± 0.27 | 1.05 ± 0.24 |

| 24 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.14 |

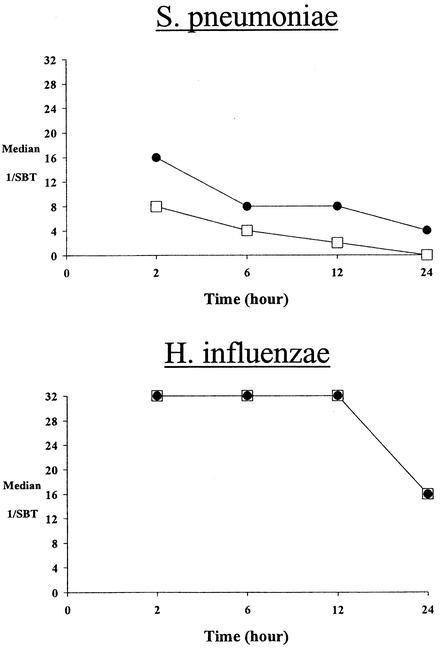

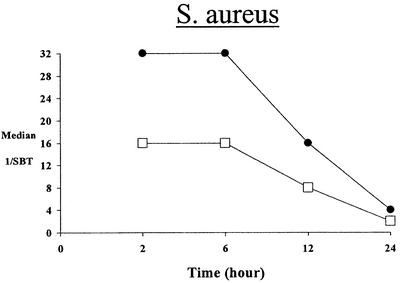

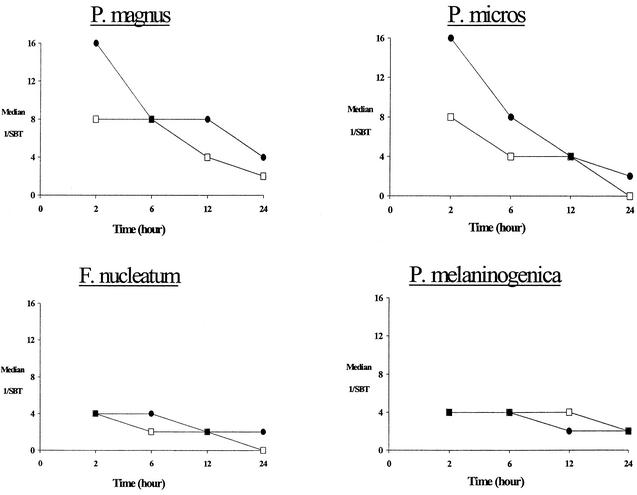

Both fluoroquinolones exhibited rapid attainment and prolonged serum inhibitory and bactericidal activity against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (Tables 3 and 4). Against the aerobic isolates, relatively high bactericidal titers in serum (1:8 to 1:32) were observed at 2 h following the dose. Moreover, prolonged (12 to 24 h) bactericidal activity in serum was observed for both drugs (Fig. 1). Against the anaerobic isolates, peak (2-h) bactericidal titers in serum were somewhat lower (1:4 to 1:16) for both gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin but still prolonged (12 to 24 h) against each study isolate (Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Median inhibitory and bactericidal titers in serum of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin over time against aerobic bacteriaa

| Organism and time point (h) | Gatifloxacin

|

Moxifloxacin

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIT (range) | SBT (range) | SIT (range) | SBT (range) | |

| H. influenzae | ||||

| 2 | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:32) |

| 6 | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) |

| 12 | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) |

| 24 | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) | 1:16 (1:16-1:32) | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) | 1:16 (1:8-1:16) |

| S. pneumoniae | ||||

| 2 | 1:8 (1:8-1:16) | 1:8 (1:4-1:8) | 1:16 (1:16-1:32) | 1:16 (1:4-1:32) |

| 6 | 1:8 (1:4-1:8) | 1:4 (1:4-1:8) | 1:16 (1:8-1:16) | 1:8 (1:8-1:16) |

| 12 | 1:4 (1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:8 (1:4-1:16) | 1:8 (1:4-1:8) |

| 24 | <1:2 (<1:2) | <1:2 (<1:2) | 1:4 (1:2-1:4) | 1:4 (1:2-1:4) |

| S. aureus | ||||

| 2 | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) | 1:16 (1:4-1:32) | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) |

| 6 | 1:16 (1:16-1:32) | 1:16 (1:4-1:16) | 1:32 (1:32) | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) |

| 12 | 1:16 (1:8-1:16) | 1:8 (1:4-1:16) | 1:16 (1:16-1:32) | 1:16 (1:4-1:32) |

| 24 | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:8 (1:8-1:16) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) |

SIT, serum inhibitory titer; SBT, serum bactericidal titer.

TABLE 4.

Median inhibitory and bactericidal titers in serum of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin over time against anaerobic bacteriaa

| Organism and time point (h) | Gatifloxacin

|

Moxifloxacin

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIT (range) | SBT (range) | SIT (range) | SBT (range) | |

| F. nucleatum | ||||

| 2 | 1:4 (<1:2-1:16) | 1:4 (1:2-1:16) | 1:4 (1:4-1:32) | 1:4 (1:4-1:32) |

| 6 | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (1:2-1:4) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) |

| 12 | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (1:2-1:4) |

| 24 | <1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | <1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:2) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:2) |

| P. melaninogenica | ||||

| 2 | 1:8 (1:4-1:16) | 1:4 (1:4-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (<1:2-1:8) |

| 6 | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:4-1:8) | 1:4 (<1:2-1:4) |

| 12 | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (1:2-1:4) |

| 24 | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) |

| P. micros | ||||

| 2 | 1:8 (1:8->1:32) | 1:8 (1:8-1:16) | 1:16 (1:8-1:16) | 1:16 (1:8-1:16) |

| 6 | 1:8 (1:2-1:16) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:8 (1:4-1:16) | 1:8 (1:4-1:8) |

| 12 | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:4) | 1:4 (1:2-1:16) | 1:4 (<1:2-1:8) |

| 24 | 1:2 (<1:2-1:2) | <1:2 (<1:2-1:2) | 1:2 (1:2-1:4) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:4) |

| P. magnus | ||||

| 2 | 1:8 (1:8-1:32) | 1:8 (1:4-1:32) | 1:32 (1:16-1:32) | 1:16 (1:16-1:32) |

| 6 | 1:8 (1:4-1:16) | 1:8 (1:2-1:16) | 1:16 (1:8-1:32) | 1:8 (1:8-1:32) |

| 12 | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:4) | 1:8 (1:4-1:8) | 1:8 (1:4-1:8) |

| 24 | 1:2 (1:2) | 1:2 (<1:2-1:2) | 1:4 (1:2-1:8) | 1:4 (1:2-1:4) |

SIT, serum inhibitory titer, SBT, serum bactericidal titer.

FIG. 1.

Median serum bactericidal titers (SBT) over time of gatifloxacin (□) and moxifloxacin (•) against aerobic isolates

FIG. 2.

Median serum bactericidal titers (SBT) over time of gatifloxacin (□) and moxifloxacin (•) against anaerobic isolates.

DISCUSSION

Trovafloxacin was the first marketed fluoroquinolone with broad-spectrum activity against anaerobic bacteria. This agent provides prolonged bactericidal activity in serum against common anaerobic pathogens and clinical efficacy for mixed aerobic-anaerobic infections (10, 30). The methoxyfluoroquinolones gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin also have broad-spectrum activity against anaerobic organisms, especially respiratory pathogens (1, 6, 15). The potency of these drugs is similar to that of trovafloxacin, and MICs are usually ≤2.0 μg/ml against anaerobes such as Peptostreptococcus spp., Prevotella spp., and Fusobacterium spp. (1, 6).

The pharmacokinetics of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin in healthy subjects has been well characterized. Gatifloxacin provides higher peak concentrations following a single 400-mg dose, but the area under the concentration-time cure is similar for these methoxyfluoroquinolones (28, 31). In this study, we found that gatifloxacin had higher concentrations in serum at the 2-h time point, but the serum levels at the other sampling times were similar for these two agents. Overall, these concentrations in serum correlated well to those observed in other single-dose studies of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin (13, 28).

Bactericidal activity in serum over time was analyzed in this study as a potential surrogate marker for antimicrobial effectiveness (33). This pharmacodynamic model was chosen because it integrates antimicrobial activity with pharmacokinetic parameters in human subjects. Serum bactericidal levels allow the evaluation of antimicrobial activity in the presence of serum factors such as antibodies, complement, and protein binding, as well as actual clinically relevant drug concentrations. Moreover, the use of serum from normal volunteers provides bactericidal values similar to those from patients when conducting serum bactericidal tests (14). The presence of serum has also been shown not to affect the susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to moxifloxacin (2).

Although AUC24/MIC ratios have been observed to be more predictive of antimicrobial effect against aerobic organisms with fluoroquinolones, the duration of killing (T > MIC) has also been shown to be a significant predictor of bacterial regrowth, especially when dose spacing is considerable (4, 7, 19). Gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin have elimination half-lives of 8 and 10 h, respectively, and are given once daily (29). In modeling techniques, the T > MIC measurement has been shown to be a good predictor of antimicrobial effects (time kill and regrowth) and useful in determining the most appropriate dosing regimen when comparing fluoroquinolones (8). Furthermore, concentration-independent killing has been observed with various fluoroquinolones against anaerobic bacteria (27). It may be that the AUC24/MIC ratio is not an inherent predictor of antimicrobial efficacy against anaerobes but useful in determining the likelihood of resistance development (26). These observations suggest that T > MIC can play an important role in bacteriologic eradication with once-daily fluoroquinolones.

In this study, we observed prolonged inhibitory and bactericidal activity with both compounds against aerobic and anaerobic respiratory pathogens. The minimum T > MIC for newer fluoroquinolones to effectively eradicate bacteria and prevent regrowth is unknown. In a pharmacokinetic model of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, a T > MIC of at least 50% of the dosing interval was necessary for preventing bacterial regrowth with gemifloxacin (19). Bactericidal activity in serum over time has also been studied in pharmacodynamic models with other antibiotics that exhibit concentration-independent killing (e.g., β-lactams) (11). Maximal killing is observed when the concentration in serum exceeds the MIC for approximately 50% or more of the dosing interval (4, 32). In this investigation, bactericidal activity in serum was observed for at least 12 h (50% of the dosing interval) against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria for both gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin. This finding suggests that these newer fluoroquinolones could provide clinically significant antibacterial effects as well as prevention of regrowth against these various isolates (17).

Our findings are also supported by other pharmacodynamic models of bacterial killing with fluoroquinolones (16, 26). The isolates utilized in our study were representative bacteria associated with respiratory tract infections and had MICs at or near the median MIC for these methoxyfluoroquinolones (1, 3, 6). All of these strains had MICs of ≤0.5 μg/ml, which would result in AUC24/MIC ratios of ≥60 following a single 400-mg oral dose of gatifloxacin or moxifloxacin in healthy volunteers (29). These ratios have been correlated to bacterial killing for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in pharmacodynamic models (12). For example, an AUC24/MIC ratio of ≥30 has been shown to be sufficient for eradication of pneumococci, and an AUC24/MIC ratio of ≥40 provided maximal killing and prevention of regrowth in strains of Bacteroides fragilis (16, 26).

In conclusion, the aim of antimicrobial therapy in respiratory tract infections should be the eradication of infecting organisms (5). We found that single oral doses of gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin provided rapid and prolonged bactericidal activity in serum against susceptible (MICs ≤ 0.5 μg/ml) aerobic and anaerobic pathogens. Our findings suggest that these methoxyfluoroquinolones could have clinical utility in the treatment of community-acquired mixed aerobic-anaerobic respiratory tract infections, such as chronic sinusitis, chronic otitis, and aspiration pneumonia.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by research grants from Bayer Corporation, West Haven, Conn., and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, N.J.

We thank David P. Nicolau for analysis of drug concentrations in serum.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann, G., R. Schaumann, B. Pless, M. Claros, E. J. C. Goldstein, and A. C. Rodloff. 2000. Comparative activity of moxifloxacin in vitro against obligately anaerobic bacteria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balcabao, I. P., L. Alou, L. Aquilar, M. Gomez-Lus, M. J. Gimenez, and J. Prieto. 2001. Influence of the decrease in ciprofloxacin susceptibility and the presence of human serum on the in vitro susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to five new quinolones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:907-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blondeau, J. M. 1999. Expanded activity and utility of the new fluoroquinolones: a review. Clin. Ther. 21:3-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig, W. A. 1998. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagan, R., K. P. Klugman, W. A. Craig, and F. Baquero. 2001. Evidence to support the rationale that bacterial eradication in respiratory tract infection is an important aim of antimicrobial therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:129-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ednie, L. M., M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1998. Activities of gatifloxacin compared to those of seven other agents against anaerobic organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2459-2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernst, E. F., M. E. Klepser, C. R. Petzold, and G. Dowen. 2002. Evaluation of survival and pharmacodynamic relationships for five fluorquinolones in a neutropenic murine model of pneumococcal lung infection. Pharmacotherapy 22:463-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Firsov, A. A., and S. H. Zinner. 2001. Use of modeling techniques to aid in antibiotic selection. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 3:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fish, D. N., and D. S. North. 2001. Gatifloxacin, an advanced 8-methoxy fluoroquinolone. Pharmacotherapy 21:35-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garey, K. W., and G. W. Amsden. 1999. Trovafloxacin: an overview. Pharmacotherapy 19:21-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guglielmo, B. J., and L. C. Rodondi. 1988. Comparison of antibiotic activities by using the bactericidal activity in serum over time. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1511-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunderson, B. W., G. H. Ross, K. H. Ibrahim, and J. C. Rotschafer. 2001. What do we really know about antibiotic pharmacodynamics? Pharmacotherapy 21:302S-318S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Honeybourne, D., D. Danerjee, J. Andrews, and R. Wise. 2001. Concentrations of gatifloxacin in plasma and pulmonary compartments following a single 400 mg oral dose in patients undergoing fibre-optic bronchoscopy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:63-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kays, M. B., R. L. White, and L. V. Friedrich. 2001. Effect of serum from different patient populations on the serum bactericidal test. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:417-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleinkauf, N., G. Ackermann, R. Schaumann, and A. Rodloff. 2001. Comparative in vitro activities of gemifloxacin, other quinolones, and nonquinolone antimicrobials against obligately anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1896-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lister, P. D. 2002. Pharmacokinetics of gatifloxacin against Streptococcus pneumoniae in an in vitro pharmacokinetic model: impact of area under the cure/MIC ratios on eradication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:69-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacGowan, A., and K. Bowker. 2002. Developments in PK/PD: optimizing efficacy and prevention of resistance. A critical review of PK/PD in in vitro models. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 19:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacGowan, A. P., K. E. Bowker, M. Wooton, and H. Holt. 1999. Exploration of the in-vitro pharmacodynamic activity of moxifloxacin for Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci of Lancefield Groups A and G. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:761-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacGowan, A. P., C. A. Rogers, H. A. Holt, M. Wolton, and K. E. Bowker. 2001. Pharmacodynamics of gemifloxacin against Streptococcus pneumoniae in an in vitro pharmacokinetic model of infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2916-2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattoes, H. M., M. Banevicius, D. Li, C. Turley, D. Xuan, C. H. Nightingale, and D. P. Nicolau. 2001. Pharmacodynamic assessment of gatifloxacin against streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2092-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1992. Methodology for the serum bactericidal test. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa.

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards Document M7-A4. 17:10-13. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2001. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria, 5th ed. Approved standard. NCCLS document M11-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 24.Nightingale, C. H. 2000. Moxifloxacin, a new antibiotic designed to treat community-acquired respiratory tract infections: a review of microbiologic and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic characteristics. Pharmacotherapy 20:245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pendland, S. L., M. Diaz-Linares, K. W. Garey, J. G. Woodland, S. Ryu, and L. H. Danziger. 1999. Bactericidal activity and postantibiotic effect of levofloxacin against anaerobes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2547-2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson, M. L., L. B. Houde, D. H. Wright, G. H. Brown, A. D. Hoang, J. C. Rotschafer. 2002. Pharmacodynamics of trovafloxacin and levofloxacin against Bacteriodes fragilis in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:203-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross, G. H., D. H. Wright, L. B. Houde, M. L. Peterson, and J. C. Rotschafer. 2001. Fluoroquinolone resistance in anaerobic bacteria following exposure to levofloxacin, trovafloxacin, and sparfloxacin in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2136-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stass, H., A. Dalhoff, D. Kubitza, and U. Schuhly. 1998. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of ascending single doses of moxifloxacin, a new 8-methoxyquinolone administered to healthy subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2060-2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein, G. E. 2000. The methoxyfluoroquinolones: gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin. Infect. Med. 17:564-570. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein, G. E., D. M. Citron, K. Tyrrell, and E. J. Goldstein. 2001. Bactericidal activity in serum of trovafloxacin against selected anaerobic pathogens. Anaerobe 7:237-240. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trampuz, A., G. Laifer, M. Wenk, Z. Rajacic, and W. Zimmerli. 2002. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of gatifloxacin against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in granulocyte-rich exudate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3630-3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogelman, B., S. Gudmudsson, J. Leggett, J. Turnidge, and W. A. Craig. 1988. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J. Infect. Dis. 158:831-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfson, J. S., and M. N. Swartz. 1985. Bactericidal activity in serum as a monitor of antibiotic therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 312:968-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xuan, D., M. Zhong, H. Mattoes, et al. 2001. Streptococcus pneumoniae response to repeated moxifloxacin or levofloxacin exposure in a rabbit tissue cage model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:794-799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]