Abstract

The genome of bacteriophage T4 encodes three polynucleotide ligases, which seal the backbone of nucleic acids during infection of host bacteria. The T4Dnl (T4 DNA ligase) and two RNA ligases [T4Rnl1 (T4 RNA ligase 1) and T4Rnl2] join a diverse array of substrates, including nicks that are present in double-stranded nucleic acids, albeit with different efficiencies. To unravel the biochemical and functional relationship between these proteins, a systematic analysis of their substrate specificity was performed using recombinant proteins. The ability of each protein to ligate 20 bp double-stranded oligonucleotides containing a single-strand break was determined. Between 4 and 37 °C, all proteins ligated substrates containing various combinations of DNA and RNA. The RNA ligases ligated a more diverse set of substrates than T4Dnl and, generally, T4Rnl1 had 50–1000-fold lower activity than T4Rnl2. In assays using identical conditions, optimal ligation of all substrates was at pH 8 for T4Dnl and T4Rnl1 and pH 7 for T4Rnl2, demonstrating that the protein dictates the pH optimum for ligation. All proteins ligated a substrate containing DNA as the unbroken strand, with the nucleotides at the nick of the broken strand being RNA at the 3′-hydroxy group and DNA at the 5′-phosphate. Since this RNA–DNA hybrid was joined at a similar maximal rate by T4Dnl and T4Rnl2 at 37 °C, we consider the possibility that this could be an unexpected physiological substrate used during some pathways of ‘DNA repair’.

Keywords: bacteriophage T4, DNA ligase, ligation, rate of nick joining, RNA–DNA hybrid, RNA ligase

Abbreviations: DraRnl, Deinococcus radiodurans RNA ligase; dsDNA (or dsRNA), double-stranded DNA (or RNA); DTT, dithiothreitol; LB, Luria–Bertani; Lig1, human DNA ligase I; NMP, nucleotide monophosphate; rNTP, ribonucleoside triphosphate; T4Dnl, T4 DNA ligase; T4Rnl1/2, T4 RNA ligase 1/2; Tm, melting temperature

INTRODUCTION

Bacteriophage T4 has a double-stranded genome of approx. 169 kb that encodes approx. 300 genes, which allow the virus to infect a range of bacteria and subvert the host cell's normal operation to create many copies of the bacteriophage [1]. Bacteriophage T4 produces several enzymes that join breaks in nucleic acids. These nucleic acid ligases join single- and double-stranded breaks in nucleic acids by the formation of phosphodiester bonds between the 3′-hydroxy group and 5′-phosphate termini at the break. Similar enzymes have been characterized from a broad spectrum of organisms [2–7], but the nucleic acid ligases from T4 have proven to be particularly valuable tools for a variety of molecular biological techniques.

T4Dnl (T4 DNA ligase) was among the first of the DNA ligases to be purified and characterized and it is encoded by gene 30 (gp30) [1,8,9]. T4Dnl joins breaks that occur in DNA and it has important roles in many different processes involved in genome metabolism. T4Rnl1 (T4 RNA ligase 1; also known as T4RnlA) was originally identified as gp63 (gene product 63), which promotes non-covalent joining of tail fibres to the bacteriophage base-plate, the final step in T4 morphogenesis [10]. Subsequently, the isolated protein was shown to be an RNA ligase, with the ligase and tail fibre attachment activities of the protein being quite distinct functions [11–13]. An in vivo function of T4Rnl1 is to repair a break in a host tRNALys (lysine tRNA), which is a defence mechanism triggered by bacteriophage activation of a host-encoded nuclease [14]. It is only relatively recently that the second RNA ligase was identified in the bacteriophage T4 genome; it is the product of gene 24.1 and is referred to as T4Rnl2 (also known as T4RnlB) [15]. Although the cellular function of T4Rnl2 is unknown, it has been proposed to be involved in RNA repair, RNA editing or as a ‘capping’ enzyme of phosphorylated RNA ends [15,16].

Along with mRNA capping enzymes, DNA and RNA ligases form a group of enzymes known as covalent nucleotidyl transferases. Nucleotidyl transferases are defined by the essential lysine residue within motif I, the first of six conserved co-linear motifs [3–6]. All nucleotidyl transferases are believed to operate through similar biochemical mechanisms consisting of three separate steps [2–6,17]. The first step involves the enzyme attacking the α-phosphate of the nucleotide co-substrate to form a covalent enzyme–NMP (nucleotide monophosphate) intermediate. The provider of NMP can be ATP, NAD+ or GTP. ATP is used by RNA ligases and some DNA ligases, including T4Dnl. In the second step of the reaction, the protein binds to the nucleic acid and the NMP is transferred from the protein to the 5′-phosphate of DNA or RNA. In the third reaction step, the backbone of the nucleic acid is sealed. Although the biochemical mechanism of all nucleic acid ligases appears similar, the use of different enzymes and substrates can give significant differences in the thermodynamics and kinetics of ligation [17].

ATP-dependent RNA ligases fall into two distinct phylogenetic groups, which are exemplified by T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 [15,18]. Very few T4Rnl1-like proteins have been identified so far and they have a narrow phylogenetic distribution, being limited to a few bacteria, baculoviruses, bacteriophages and fungi [19,20]. T4Rnl2-like proteins have a much wider distribution and are found in all three phylogenetic domains. They include RNA ligases encoded by vibriophage, mycobacteriophage, eukaryotic viruses and archaea [15] and mRNA editing ligases of Trypanosoma and Leishmania [21,22].

High-resolution structures of several nucleic acid ligases have been obtained [5–7,23]. These studies demonstrate that DNA ligases exhibit a modular structure, with a common core required for adenylation linked to other domains that bind substrate. Although no structure has been reported for T4Dnl, it is likely to have a similar conformation to the core of other ATP-dependent DNA ligases [5–7]. Recent X-ray crystallographic studies have elucidated the structure of the adenylation domain of T4Rnl2 at 1.9 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) [24]. In addition, the crystal structure has been reported for complete T4Rnl1 in complex with pp[CH2]pA (adenosine 5′-[α,β-methylene]triphosphate), an analogue of ATP [25].

The only high-resolution structure for a nucleic acid ligase associated with its nucleic acid substrate was obtained recently for Lig1 (human DNA ligase I), which revealed that the enzyme encircles the nicked 5′-adenylated DNA intermediate [7,26]. The protein was observed to induce an under-wound conformation of the DNA, widening the major and minor grooves over six base-pairs. Thus the section of DNA upstream of the nick (i.e. that containing the 3′-hydroxy group) had an A-form conformation, whereas the DNA downstream of the nick was more typical of the B-form conformation. Interestingly, inclusion of RNA upstream of the nick is compatible with the A-form helix seen in the Lig1–DNA complex and the RNA can be ligated to downstream DNA [7,26]. In contrast, RNA downstream of the nick inhibited ligation.

Nick joining between a ribonucleotide containing the 3′-hydroxy group and deoxyribonucleotide containing the 5′-phosphate has also been confirmed for other nucleic acid ligases. These include the bacterial cellular enzyme DraRnl (Deinococcus radiodurans RNA ligase) [19] and the viral enzymes Chlorella PBCV-1 (Paramecium bursaria chlorella virus-1) DNA ligase [27] and Vaccinia DNA ligase [28]. T4Rnl2 has also been shown to join nicks in such RNA–DNA hybrids [29–31]. The ability of T4Rnl2 and DNA ligases to join nicks in similar substrates lends support to ideas that all nucleotidyl transferases are derived from a common ancestor. This point is emphasized on comparison of structural data from DNA ligases, T4Rnl2 and capping enzymes, leading to the suggestion that T4Rnl2 is likely to be most similar to the common ancestor of all of these enzymes [6,24,29].

Many studies have confirmed that native and recombinant forms of the T4 nucleic acid ligases are able to join a diverse set of substrates, including single-stranded and double-stranded molecules. A wide array of substrates for T4Dnl was identified during early characterization of the enzymes (reviewed in [2,32–34]). The variety of substrates used by T4Dnl has been extended by recent studies, particularly in relation to use of the enzyme in biotechnological applications (e.g. [35,36]). T4Rnl1 can also use a variety of substrates, including DNA, to form a range of different products (reviewed in [32–34]). For T4Rnl2, detailed biochemical and mutagenesis experiments have highlighted the interactions formed between the protein, the donor nucleotide, and RNA [15,16,24,30,37]. In spite of the distinct biochemical activities of T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2, it is clear that they can each ligate related types of nucleic acids. However, there are no published studies that have directly compared the activities of all of these proteins.

To assess whether there is potential for the T4 nucleic acid ligases to be active against the same substrates and, therefore, influence the activity of each other within a cellular environment, we performed a systematic biochemical analysis of the ability of each protein to join nicks in a variety of double-stranded nucleic acids. Building on previous knowledge about the ligation activities of these proteins, we demonstrate that T4Dnl and T4Rnl2 have similar rates of nick joining for some RNA–DNA hybrids. Analysis of the spectrum of substrates that are ligated allows speculation on the in vivo functions of such activities.

EXPERIMENTAL

Growth of bacterial cultures

Details of bacterial strains and plasmids have been described previously [38–40]. Growth of Escherichia coli was monitored at a variety of temperatures on plates and in liquid cultures. In all cases, LB (Luria–Bertani) broth was the nutrient medium. Antibiotics were added to media as required, with final concentrations of ampicillin at 100 μg·ml−1 and chloramphenicol at 50 μg·ml−1. Stock cultures containing 25% (v/v) glycerol were stored at −80 °C and used to streak on to fresh LB-agar plates as required. Bacterial cells were made chemically competent for DNA transformation and stored in 200 μl aliquots at −80 °C [41].

Cloning of nucleic acid ligases

Bacteriophage T4GT7 genomic DNA was kindly provided by Dr Borries Kemper (University of Köln, Köln, Germany). Cloning of the nucleic acid ligases from T4 was performed following the strategies employed for bacterial NAD+-DNA ligases described previously [38–40]. Briefly, the genes were amplified by PCR with a proofreading DNA polymerase from genomic DNA using the following primers: full-length T4Dnl (487 amino acids, 55.3 kDa) was amplified using 5′-primer (5′-CATATGATTCTTAAAATTCTGACC-3′) and 3′-primer (5′-GGATCCTCATAGACCAGTTACCTCATG-3′). Full-length T4Rnl1 (374 amino acids, 43.5 kDa) was amplified using 5′-primer (5′-CATATGCAAGAACTTTTTAACAATTTAATG-3′) and 3′-primer (5′-GGATCCTTAGTATCCTTCTGGGATAAATTTTT-3′). Full-length T4Rnl2 (334 amino acids, 37.6 kDa) was amplified using 5′-primer (5′-CATATGTTTAAAAAGTATAGCAG-3′) and 3′-primer (5′-GGATCCTTAACTTACCAACTCAATCC-3′).

To aid cloning into the expression vector, note that the 5′-primer contained an additional NdeI site and the 3′-primer contained a BamHI site. PCR products were cloned using the Zero Blunt TOPO® Cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequenced to confirm that the recombinant gene was as required. Fragments were excised from the TOPO vectors using the NdeI and BamHI sites and cloned into pET-16b (Novagen). Proteins overexpressed from this vector contain a His10 tag within 21 additional amino acids (2.5 kDa) at the N-terminus.

To allow overexpression of proteins in E. coli GR501, fulllength ligases plus the His tag were excised from pET-16b vectors using the NcoI and BamHI sites and cloned into pTRC99A (Amersham Biosciences). Additional plasmids expressing proteins used to provide positive and negative controls of in vivo ligation have been described previously [38–40].

Protein purification

For protein expression, all E. coli cultures were grown in LB containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. The pET16b derivatives were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS, and cells were plated on to LB agar containing antibiotics and grown overnight at 37 °C. Single colonies were inoculated into 5 ml of liquid media, grown overnight at 37 °C and diluted 100-fold into fresh media (50 ml–1 litre). After growth to mid-exponential phase (D600=0.5), protein expression was induced by addition of isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside to 0.4 mM. After incubation at 25 °C for 20 h, cells were harvested, sonicated and centrifuged to separate soluble and insoluble fractions. Proteins were purified from the soluble fraction using columns with affinity for the His tag (Amersham Pharmacia HiTrap™ Chelating HP). Fractions eluting from the column were analysed by SDS/PAGE in order to confirm which contained the protein. Fractions containing the purified protein were pooled together in volumes of 2.5 ml and the buffer was exchanged using disposable PD-10 desalting columns (Amersham Biosciences, U.K.). The manufacturer's method was used and the proteins were eluted in 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol) and 10% glycerol. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Protein Assay). In general, standard amounts of pure protein obtained from each litre of induced culture were 1.3 mg for T4Dnl, 1.9 mg for T4Rnl1 and 1.7 mg for T4Rnl2. For long-term storage at −80 °C, glycerol was added to a final concentration of 30%.

Analysis of ligation activity

In vitro assays of ligation activity were performed using a double-stranded substrate like that described previously [38–40], except that the substrate was 20 bp and the nick was between bases 8 and 9. Oligonucleotides were purchased from MWG-Biotech (Germany). The dsDNA (double-stranded DNA) substrate was created by annealing an 8-mer (5′-GGCCAGTG-3′) and a 12-mer (5′-AATTCGAGCTCG-3′) to a complementary 20-mer (5′-CGAGCTCGAATTCACTGGCC-3′). At their 5′-ends, the 8-mer contained a fluorescein molecule and the 12-mer was phosphorylated. Annealing of oligonucleotides was performed by mixing 3 nmol of each of the oligonucleotides in a total volume of 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, and 0.5 mM EDTA). The samples were heated to 100 °C for 5 min and allowed to cool overnight. While heating and cooling, the substrates were covered to prevent the de-activation of fluorescein by light.

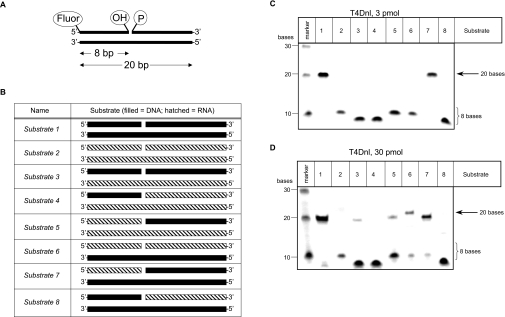

Following the same procedures, substrates were also prepared in which RNA replaced the DNA; in these cases, the sequences were identical, except that U replaced T. RNA oligonucleotides (Dharmacon, U.S.A.) were de-protected and stored following the manufacturer's instructions. Substrates were prepared using all combinations of RNA and DNA substrates and were referred to as substrates 1–8 (see Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Ligation activity of T4Dnl on a range of substrates.

The nick-joining activity of T4Dnl was tested on 20 bp double-stranded substrates containing differing fragments of DNA and RNA. (A) Overview of substrates used in assays of in vitro nucleic acid ligation activity. The diagram illustrates the position of the 5′- and 3′-ends, the fluorescein reporter group (Fluor) and the phosphate (P) and hydroxy (OH) groups at the nick. Note that, if ligation occurs, the size of the nucleic acid attached to fluorescein increases from 8 to 20 bases. (B) Schematic diagram of the substrates used in the ligation assay, indicating the position of the 5′- and 3′-ends and with DNA and RNA being represented by filled and hatched boxes respectively. (C, D) In vitro ligation assays performed at 37°C for 30 min with the various substrates (45 pmol) and indicated amounts of protein. The marker contained a mixture of fluorescein-labelled oligonucleotides of the specified size.

The nicked 20 bp substrates were used in end-point and time-course assays of the in vitro ligation activity of each enzyme. The buffer used for all reactions was 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT and 1 mM ATP. End-point reactions were performed as follows: 2–70 pmol of ligase, 45 pmol of oligonucleotide substrate in a total volume of 5 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and then stopped using 5 μl of formamide stop solution [41]. The effect of pH on the extent of ligation was examined by performing assays in reaction buffer as indicated above except that it contained Tris-acetate (pH 4–7) or Tris/HCl (pH 7–9); measurements of the pH of all solutions were performed at 20 °C. Time-course reactions were performed as follows: 2–1600 pmol of ligase, 540 pmol of oligonucleotide substrate in a total volume of 60 μl. The reaction mixture was incubated at temperatures from 4 to 37 °C, with 5 μl aliquots being removed at various time points as indicated and added to 5 μl of formamide stop solution.

At the end of all experiments, samples were heated in a boiling-water bath for 3 min and analysed on a 15% polyacrylamide–urea gel (8.3 cm×6.2 cm) in 0.5×TBE (90 mM Tris, 90 mM boric acid, pH 8.3, and 2 mM EDTA). Reaction products on the gel were visualized using a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX. Quantification was performed using the public domain NIH Image/J program (developed at the National Institutes of Health Bethesda, MD, U.S.A., and available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/). For time-course experiments, the extent of ligation was expressed as mole of ligated product per mole of ligase per minute of reaction time. The initial rates of reactions were measured from the extent of ligation in the first 4 min of the reactions and reported measurements were the average of three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Cloning and purification of T4Dnl and T4Rnl2

The DNA ligase of T4 is encoded by gene 30 (gp30). The genome of T4 encodes two RNA ligases: T4Rnl1 is encoded by gene 63 and T4Rnl2 is encoded by gene 24.1. All of these proteins have been shown to join nicks in double-stranded nucleic acids [1] and we investigated the specificity and rates of these activities using recombinant forms of the proteins. The appropriate genes were cloned into the bacterial expression vector pET-16b, overexpressed and purified by affinity chromatography to an in-frame N-terminal His tag, as has been used in studies of a number of different nucleic acid ligases [15,16,24,29,30,37–40]. When taking account of the addition of the His tag from pET-16b, the total molecular masses of proteins used in the present study were: T4Dnl=57.8 kDa, T4Rnl1=46 kDa and T4Rnl2=40.1 kDa. Analysis on SDS/PAGE showed the His-tagged proteins were >90% pure (see Supplementary Figure 1 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/398/bj3980135add.htm). For T4Rnl1, two clear bands of protein could be observed, relating to adenylated and non-adenylated protein, as reported previously [42].

Nick-joining ligation activity of T4Dnl and T4Rnl2

The T4 nucleic acid ligases have been demonstrated to join nicks in double-stranded nucleic acids with varying efficiencies (reviewed in [6,32–34]). However, no studies have compared the activities of the enzymes under identical conditions, so it has been difficult to predict how these proteins will influence each other's activity within a cellular environment. To begin to address such queries, we determined the activity of T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 on a range of substrates using the biochemical assay of denaturing gel electrophoresis to detect increases in length of an oligonucleotide upon ligation. The substrates used here were a modification of those used previously [38–40] and consisted of a 20 bp double-stranded oligonucleotide containing a gap between bases 8 and 9 of one strand (Figure 1A). Each of the three individual strands was prepared with ribo- and deoxyribo-nucleotides. By appropriate mixing of each strand, eight different combinations of double-stranded, nicked nucleic acids were prepared (Figure 1B). These consisted of DNA only (substrate 1), RNA only (substrate 2) and a variety of DNA–RNA hybrids (substrates 3–8).

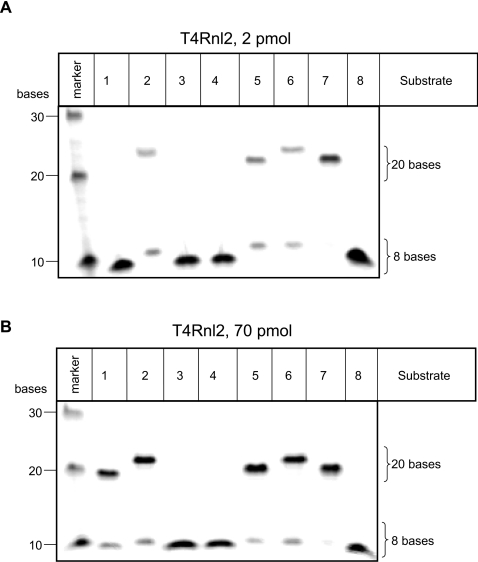

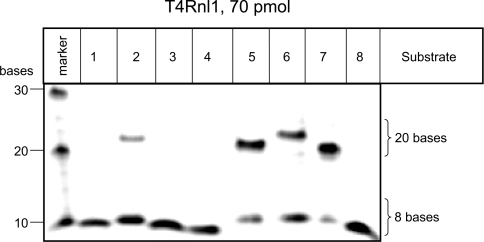

All proteins purified in the present study demonstrated nick-joining activity of several substrates in the presence of ATP and, thus, were confirmed to have nucleic acid ligase activity (Figures 1–3). Reactions performed with excess substrate identified the preferred substrates as follows: for T4Dnl it was substrates 1 and 7 (Figure 1C, 3 pmol); for T4Rnl2 it was substrates 2, 5, 6 and 7 (Figure 2A, 2 pmol); no significant nick-joining activity was observed for T4Rnl1 under similar conditions (results not shown). Reactions performed with higher amounts of enzyme identified that additional substrates were ligated by T4Dnl (Figure 1D, 30 pmol) and T4Rnl2 (Figure 2B, 70 pmol), and detected nick-joining activity for T4Rnl1 with some substrates (Figure 3, 70 pmol). Thus the different proteins were able to ligate similar double-stranded nucleic acids, although they had optimal activity with a different subset of substrates.

Figure 2. Ligation activity of T4Rnl2 on a range of substrates.

The nick-joining activity of T4Rnl2 was tested on 20 bp double-stranded substrates containing differing fragments of DNA and RNA (see Figures 1A and 1B for details). (A, B) In vitro ligation assays performed at 37°C for 30 min with the various substrates (45 pmol) and indicated amounts of protein. The marker contained a mixture of fluorescein-labelled oligonucleotides of the specified size.

Figure 3. Ligation activity of T4Rnl1 on a range of substrates.

The nick-joining activity of T4Rnl1 was tested on 20 bp double-stranded substrates containing differing fragments of DNA and RNA (see Figures 1A and 1B for details). In vitro ligation assays performed at 37°C for 30 min with the various substrates (45 pmol) and indicated amount of protein. The marker contained a mixture of fluorescein-labelled oligonucleotides of the specified size.

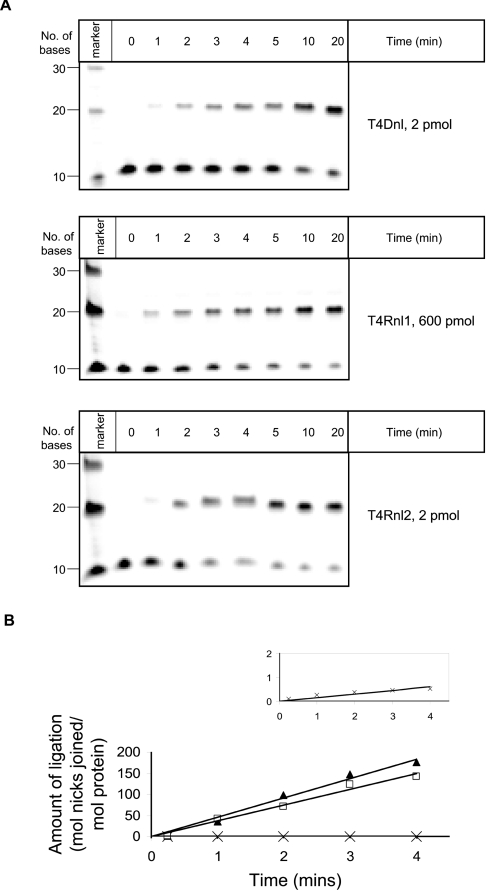

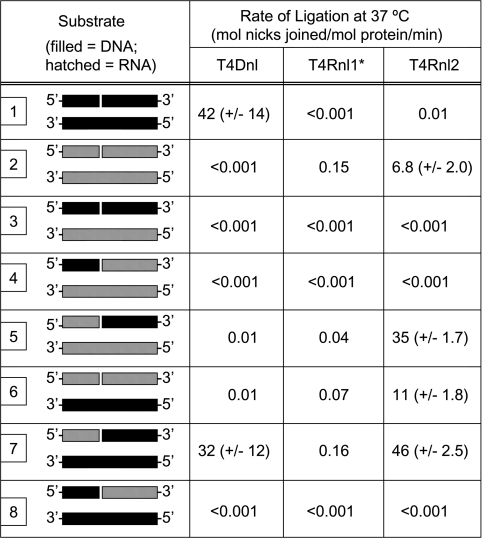

The end-point reactions clearly identified that the three proteins performed different extents of ligation across the range of substrates. To provide a more accurate determination of the nick-joining activity of each enzyme on the various substrates, time-course experiments were performed. Representative examples of gels are shown for each of the enzymes with substrate 7 (Figure 4A). The extent of ligation at each time-point was quantified and the initial rates of nick joining were determined (Figure 4B) and the complete data set is collated in Table 1. These data confirmed that each protein ligated several substrates, although none of the proteins had significant nick-joining activity with substrates 3, 4 or 8. With substrates containing only DNA or RNA, there was a clear pattern of substrate preference between the various proteins. The dsDNA (substrate 1) was ligated most effectively by T4Dnl, with the rate of 42 ligation events·min−1 being in agreement with previous studies that used oligonucleotides of similar sizes [43]. In contrast, significant ligation of dsRNA (double-stranded RNA) could only be detected for T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2. Thus experiments that used dsDNA or dsRNA support the traditional nomenclature of the nucleic acid ligases encoded by bacteriophage T4 and support proposals that these proteins have specific molecular requirements at the nick [5,6].

Figure 4. Determination of the rates of ligation of different substrates by T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2.

(A) In vitro ligation assays performed for various times at 37 °C with substrate 7 (540 pmol) and indicated amounts of protein. The marker contained a mixture of fluorescein-labelled oligonucleotides of the specified size. (B) The extent of nick joining in the experiment shown in (A) was quantified for T4Dnl (open square), T4Rnl1 (cross) and T4Rnl2 (closed triangle). The inset shows an enlarged plot of the results with T4Rnl1. Initial rates of nick joining were calculated from triplicate experiments and are recorded in Table 1. For clarity, error bars are not included in the graphs, but the S.D. of the measurements are included in Table 1.

Table 1. Rates of nick joining of a range of double-stranded nucleic acids by T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2.

Rates for T4Dnl and T4Rnl2 are the means for triplicate experiments, with the S.D. indicated. All measurements are shown to two significant figures. The diagram indicates the position of the 5′- and 3′-ends, with DNA and RNA being represented by closed and hatched boxes respectively; see Figures 1(A) and 1(B) for full details.

*Rates for T4Rnl1 are from a single time-course experiment.

Experiments with RNA–DNA hybrids identified that T4Dnl and T4Rnl2 have significant cross-over of substrate specificity in their nick-joining reactions. Interestingly, for substrate 7, the rate of ligation by T4Dnl was 32 ligation events·min−1, similar to its rate with dsDNA, substrate 1 (42 ligation events·min−1). Correspondingly high rates of nick joining were observed with T4Rnl2 and substrates 5 and 7, with ligation rates of 35 and 46 min−1 respectively (Table 1). T4Rnl2 had an intermediate nick-joining rate for substrate 6 of 11 min−1, similar to its activity with dsRNA (substrate 2). To obtain rates of ligation of T4Rnl1 above the detection limits of the assay, large amounts of protein had to be added to the time-course reactions. This situation is not ideal for measurements of initial rates, since not all of the enzyme can participate in the reaction. However, if it is assumed that all of the protein is similarly competent for nick joining, T4Rnl1 ligated substrates 5–7 at 0.04–0.16 ligation events·min−1, similar to its activity with substrate 2 (dsRNA). These estimates agree with previous studies showing that T4Rnl1 ligates several types of nucleic acid at low rates [6,32–34]. Notably, ligation rates for T4Rnl1 were 50–1000-fold less than rates for T4Rnl2 with the same substrates.

To compare the activity of the T4 enzymes used here with other nucleic acid ligases, we determined their ability to ligate a 40 bp dsDNA substrate used previously [38–40]. Note that the central sequence of the 40 bp dsDNA substrate was identical with that of the 20 bp dsDNA (substrate 1) used in the present study. No nick joining of 40 bp dsDNA was observed for T4Rnl1 or T4Rnl2, in agreement with their low level of activity with substrate 1 (results not shown). T4Dnl ligated the nick in the 40 bp dsDNA at a rate of approx. 11 ligation events·min−1, a notably lower rate than that observed with substrate 1 (Table 1).

Thus the recombinant T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 prepared in the present study have nick-joining activity with double-stranded substrates that corresponds to the traditional view of the three enzymes. In other words, T4Dnl is able to join nicks in dsDNA but not dsRNA, whereas T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 have reversed activities. Kinetic analysis of ligation of RNA–DNA hybrids identifies that the different proteins have similar levels of activity on some of the same molecules, an observation that has not been fully appreciated in previous studies that analysed the proteins separately [1,2,6].

Effect of temperature and pH on nick-joining activity of T4 nucleic acid ligases

Results presented above show that the recombinant T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 prepared in the present study have nick-joining activity with various double-stranded RNA–DNA hybrids. To assess whether ligation of such nucleic acids may be an intrinsic function of these enzymes, at least in biochemical terms, we characterized the ligation of different substrates across a range of pH values and temperatures.

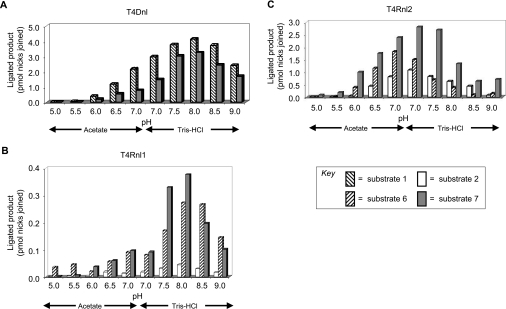

Experiments to determine the pH of the optimal activity of the enzymes with different substrates were performed at 37 °C from pH 4 to pH 9. Two different buffers were used for this range [15,24,37]: experiments at pH 4–7 were performed with Tris-acetate and those at pH 7–9 were performed with Tris/HCl. All other components of the reaction were unchanged. For T4Dnl, optimal nick-joining activity was observed at pH 8 for both substrate 1 and substrate 7 (Figure 5A). For T4Rnl1, the overall amount of ligation was very low and the activity with some substrates extended across the whole range, but optimal nick-joining activity was observed at pH 8 for substrates 2, 6 and 7 (Figure 5B). In contrast, although T4Rnl2 ligated the same substrates as T4Rnl1, its optimal nick-joining activity was observed at pH 7 (Figure 5C). Importantly, for all proteins, the optimal activity was observed at the same pH for all substrates.

Figure 5. Effect of pH on nick-joining activity of T4 nucleic acid ligases.

Nicked 20 bp substrates were used in assays of the in vitro ligation activity of each enzyme at various pH values. The buffer used for all reactions was identical except that it contained Tris-acetate (pH 4–7) or Tris/HCl (pH 7–9). Quantification of the extent of nick joining is presented for those substrates giving significant ligation with T4Dnl (A), T4Rnl1 (B) and T4Rnl2 (C). Shading of the bars relates to specific substrates as indicated in the key. See Figures 1(A) and 1(B) for details of substrates.

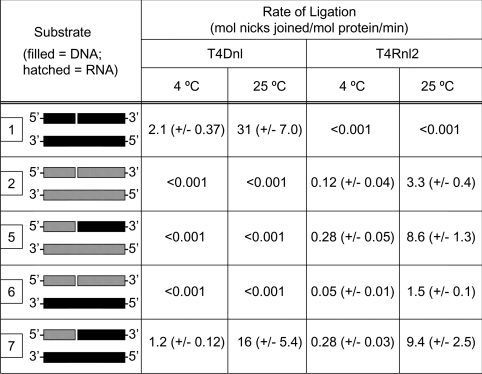

To allow comparison with experiments performed at 37 °C (Table 1), examination of the temperature dependence of nick joining for different substrates was performed at pH 7.5. Significant nick joining could not be detected for T4Rnl1 at temperatures of 25 °C and below (results not shown), in accordance with its low rates at 37 °C (Table 1). As expected, T4Dnl and T4Rnl2 ligated similar substrates at all temperatures, albeit at lower rates at decreasing temperatures (Table 2). Notably, for both proteins, the preferred substrates were similar at all temperatures e.g. T4Rnl2 always ligated substrates 5 and 7 better than substrates 2 and 6. At the lower temperatures, the measured rates of ligation were significantly higher for T4Dnl compared with T4Rnl2. Furthermore, for T4Dnl, substrate 1 was ligated significantly better than substrate 7, consistent with double-stranded DNA being the optimal substrate for T4Dnl.

Table 2. Effect of temperature on the rates of nick joining of double-stranded nucleic acids by T4Dnl and T4Rnl2.

Rates are the means for triplicate experiments, with the S.D. indicated. All measurements are shown to two significant figures. The diagram indicates the position of the 5′- and 3′-ends, with DNA and RNA being represented by closed and hatched boxes respectively; see Figures 1(A) and 1(B) for full details.

DISCUSSION

Bacteriophage T4 encodes three polynucleotide ligases, which have been widely studied and act as model systems for this class of enzymes. Traditionally, these three proteins have been referred to as T4Dnl (gp30), T4Rnl1A (gp63) and T4Rnl2 (gp24.1). This nomenclature is based on activities initially assigned to each protein product from in vitro experiments. The present study compares the nucleic acid substrate specificity for each of these enzymes. Using a range of double-stranded nucleic acids, we confirm that each enzyme has good nick-joining activity as identified in their original description. In addition, we show that these proteins have high rates of nick joining for other double-stranded substrates, leading to questions about the in vivo significance of these observations and whether there may be overlap between the cellular roles of the enzymes.

The substrates used in the present study consisted of all combinations arising from the hybridization of three RNA and/or DNA oligonucleotides (Figures 1A and 1B). In line with expectation from previous studies [2,6,30,33], rates of nick joining varied for the different proteins and substrates. This variation in rates of nick joining identifies that the biochemical parameters of the reaction mechanism are altered as each protein ligates a different substrate. The variation in rates could be explained by altered binding affinity between the proteins and substrates, or adaptations in other steps of the mechanism, including transfer of the adenylate group from protein to nucleic acid or the ligation step itself. We have not analysed which of these specific parameters influence the rates of nick joining, but it is likely that more than one of them may be important and the different proteins may be affected at different steps.

Determination of the rates of nick joining for all substrates was performed at a range of pH from 4 to 9 and temperatures from 4 to 37 °C. In these experiments, the range of substrates ligated was unchanged. Experiments with pairs of oligonucleotides were unable to detect joining of single-stranded nucleic acids by T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 or T4Rnl2 under the conditions used here (results not shown). This observation is consistent with the low rates observed for such template-independent ligation [36]. In contrast, efficient nick joining was detected for double-stranded, nicked molecules consisting of DNA alone, RNA alone and a variety of RNA–DNA hybrids. The maximal rates of ligation measured here (30–50 nicks joined per minute by each protein molecule) are in line with previous studies that have used similar substrates and experimental conditions to study T4Dnl [43] and T4Rnl2 [30]. Both RNA ligases joined the same set of substrates, but the nick-joining rates for T4Rnl1 were 50–1000-fold less than the rates for T4Rnl2. Most applications of RNA ligases tend to focus on T4Rnl1, understandably since it is more easily available on a commercial basis. The present study demonstrates that T4Rnl2 acts much more efficiently than T4Rnl1 for all ligation events using double-stranded templates, which would include ‘splinted’ ligation [34].

For T4Dnl, significant amounts of nick joining were observed only when the complementary strand was DNA, but the nicked strand could be DNA alone (substrate 1) or RNA containing the 3′-hydroxy group and DNA containing the 5′-phosphate (substrate 7). T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 were also able to ligate the nick in substrate 7, but not substrate 1, illustrating that the ‘RNA’ and ‘DNA’ ligases have different specificity in relation to their nucleic acid substrates. This is demonstrated further by the observation that T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 ligated a wider selection of substrates, joining molecules in which the complementary strand was DNA or RNA. Importantly, none of the enzymes could join a nick if the 5′-phosphate was provided by an rNTP (ribonucleoside triphosphate) and the complementary strand was DNA; this result is consistent with recent studies of T4Rnl2 [29,31] and DraRnl from D. radiodurans [19].

The pH for optimal activities in any nick-joining reaction was determined by the protein, with optimal ligation for T4Dnl and T4Rnl1 obtained at pH 8 and for T4Rnl2 at pH 7. Such ‘bell-shaped’ pH curves have been observed previously for a variety of nucleic acid ligases. In agreement with results presented here, T4Rnl2 ligated various nucleic acids at pH optima of 6–7 [15,16,30,37]. Similar pH optima have been observed for other ‘RNA ligases’ [19,20,44], although a related enzyme recently characterized from Thermus scotoductus had optimal activity at pH 8 [45]. Although the pKa has been determined for adenylation of T4Dnl [43,46], the pH optimum for ligation by T4Dnl has not been reported for substrates like those used here. However, our observed optima of ligation at approximately pH 8 are consistent with known properties of the enzyme [2,32,33]. Since the experiments reported here show that the nucleic acid ligases have different pH optima for ligation of the same substrates (substrate 7), the determinant for these optima must be specific to the protein rather than the type of ligation being performed. The difference in pH optima for T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 highlights that this parameter cannot be used to identify the pattern of substrate preference for nucleic acid ligases. This observation is supported by the findings of different pH optima for similar ‘RNA ligases’ [44,45] and by the fact that a protein from a thermophilic archaeon can ligate nicks in dsDNA with an optimum of approximately pH 7 [47], i.e. more like T4Rnl2 than T4Dnl.

Upon increase of reaction temperature from 4 to 37 °C, the activity of both T4Dnl and T4Rnl2 increased, as observed with most enzymes across this temperature range. The measurements with T4Dnl and substrate 1 lead to a value of 1.4 for its Q37°25° (the ratio of activity at 37 °C compared with that at 25 °C). The agreement with previous analysis of the Q37°25° value of T4Dnl [9] is remarkable given the differences in buffer conditions, substrates and protein preparations. Although the nick-joining activities of T4Dnl and T4Rnl2 increased as the temperature of the reactions was raised from 4 to 37 °C, both proteins had the same preferred substrates at all temperatures. However, careful analysis of the data shows that the magnitude of the increase in rate with temperature was different for the proteins and their various substrates. For example, at 4 °C, the maximal rates of ligation were significantly higher for T4Dnl compared with T4Rnl2, with substrate 1 (dsDNA) being ligated most efficiently, but at 37 °C the maximal rates were similar for both proteins. In quantitative terms, the Q37°25° values varied depending on the protein and substrate, with T4Rnl2 and substrate 7 having the largest Q37°25° of 4.9.

The variation in observed rates of nick joining across this range of temperatures suggests that at least one step in the reaction mechanism is sensitive to the nucleic acid substrate and that it may have a different rate for T4Dnl and T4Rnl2. As pointed out above, this could indicate that there is variation in the binding affinities between the different proteins and different substrates, or it could relate to some other aspect of the interaction between protein and substrate. The convergence of observed rates at the higher temperature suggests that the same step in the reaction mechanism may become rate-limiting for both proteins with their optimal substrates. Since they are in line with other studies using similar conditions [30,43], the measured rates of T4Dnl or T4Rnl2 at 37 °C with their preferred 20 bp substrates may be approaching their maximal rates. Alternatively, the convergence in observed rates at 37 °C may reflect effects of the experimental conditions on the nucleic acid substrate. The nucleic acids used in the present study are relatively short, which leads to correspondingly low values for their Tm (melting temperature). The various substrates used in the present study will have different Tm values, as can be predicted using detailed thermodynamic analyses of nucleic acids [48], and the substrate with the lowest predicted Tm is that consisting only of DNA (substrate 1). Thus the reason why there was not such a large increase in observed rates for this substrate could be because it was more prone to denaturation as the temperature was increased. Attempts to preclude this effect by using larger substrates are not straightforward, as indicated by the lower rate of nick joining for T4Dnl with a 40 bp dsDNA compared with the 20 bp dsDNA, and also observed previously with other substrates [43]. This effect of nucleic acid size on the rate of ligation may be simply due to the fact that larger substrates have an increased number of total base-pairs per nick, which may interact with the protein in a non-specific manner and alter its availability at the nick. The conclusive explanation for the effect of size on the rate of ligation will require a systematic study of the relationship between these parameters.

Of the proteins analysed here, T4Dnl is the only one that gives good nick joining of dsDNA. However, the low amount of nick joining observed with T4Rnl2 and dsDNA (substrate 1) led us to question whether this enzyme could act on such substrates in vivo, especially if it was present at high concentrations. To test this possibility, we expressed the recombinant proteins in E. coli GR501. This strain contains a mutation in chromosomal-encoded E. coli LigA, which produces a temperature-sensitive strain that has proved useful for in vivo analysis of ligation activity [38–40]. Upon overexpression of proteins in E. coli GR501, T4Dnl allowed growth, whereas T4Rnl1 or T4Rnl2 did not allow growth at the normally non-permissive temperature (results not shown). These observations are consistent with T4Dnl being the only T4-encoded protein that can seal nicks in DNA produced during replication.

Potential for RNA–DNA hybrids to be substrates for nucleic acid ligases in cells

Although the present in vitro study makes it clear that the T4 nucleic acid ligases can join a variety of nicked, double-stranded nucleic acids, it is also apparent that the enzymes cannot join all possible substrates consisting of DNA and RNA. Clearly, the enzymes must be able to detect the type of nucleotide present at the nick, supporting the observations made in a series of studies of T4Rnl2 [29–31]. We show that some RNA–DNA hybrids are joined as efficiently and with similar temperature and pH profiles as the ‘traditional’ substrates of T4Dnl, T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 (i.e. substrates consisting only of DNA or RNA respectively). Thus, if such substrates arise in vivo, they are likely to be ligated efficiently. The available evidence suggests that it is now important to address if these activities are significant in relation to the cellular functions of these enzymes.

In evaluating the importance of observations such as those reported here, it is necessary to question how they relate to in vivo situations relevant to infection of cells by bacteriophage T4. Nicks in molecules that only contain dNTPs arise during many aspects of DNA metabolism and the present study makes it clear that only T4Dnl can join these (see Supplementary Figure 2A at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/398/bj3980135add.htm). Recent observations have suggested that bacterial cells invest in repair of RNA molecules [49,50], and repair of a tRNA is an important physiological function of T4Rnl1 [1,51]. The experiments performed here demonstrate that T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 can join breaks in RNA (substrates 2 and 6), but T4Dnl is unlikely to participate in the repair of nicks in molecules containing only rNTPs.

In relation to the present study, the most interesting results to evaluate are those involving analysis of RNA–DNA hybrids. Due to an increased chemical instability, RNA is generally considered to be undesirable within genomes since this is likely to lead to higher genome instability. So, are the nucleic acid ligases likely to encounter RNA–DNA hybrids in vivo? During replication of double-stranded genomes, DNA synthesis on the lagging-strand is initiated from an RNA primer. If the rNTPs are not removed quickly, nicks may be present in the genome that contains the 3′-hydroxy group on a dNTP and the 5′-phosphate on an rNTP (see Supplementary Figure 2B at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/398/bj3980135add.htm). To ensure that the RNA is not incorporated into the genome on a long-term basis, the nucleic acid ligases should not join these nicks efficiently [52]. Consistent with this hypothesis, the RNA–DNA hybrid containing RNA downstream of the nick and DNA upstream (substrate 8) was not ligated efficiently by any of the T4 nucleic acid ligases. Previous studies have also observed that RNA downstream of a nick inhibits ligation by nucleic acid ligases [19,26–29]. Thus it appears that the evolution of nucleic acid ligases has helped to ensure low incorporation of RNA from the genome Okazaki fragments during typical growth conditions.

What about RNA–DNA hybrids containing RNA upstream of the nick, such as substrate 7? All of the T4 nucleic acid ligases were able to ligate nicks in this molecule, with the observed rates at 37 °C being equivalent to the optimal activity of the enzymes. This observation agrees with experiments performed with similar substrates for T4Rnl2 [6,29,30], and is consistent with characterization of substrate specificity for T4Dnl [2,32,33]. It is also known that this type of RNA–DNA hybrid can be ligated by other DNA ligases [19,26–28]. So, are such RNA–DNA hybrids likely to be encountered in the cell? A number of recent studies have identified that some DNA polymerases have relaxed specificity for the nucleotides they use and may frequently incorporate rNTPs [53–57]. Such an activity may lead to the presence in genomes of RNA–DNA hybrids similar to substrate 7 used in the present study. The in vitro ligation of this nucleic acid substrate may simply reflect the fact that the T4 enzymes have promiscuous active sites and this type of ligation may have no in vivo function [56]. However, it may be that this activity is useful to bypass certain types of DNA damage or under conditions of large amounts of DNA synthesis, as would be experienced during extensive genome damage or infection of cells by replicating viruses. The concentration of rNTPs in bacteria is approx. 10-fold higher than dNTPs [58], so at times of large amounts of DNA synthesis it is likely that the availability of dNTPs might be limiting, leading to a higher utilization of rNTPs (see Supplementary Figure 2C at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/398/bj3980135add.htm). Even though it is not an ideal situation, it could be that the incorporation of RNA may act as a ‘quick fix’ that allows the cell to survive, before allowing faithful repair with dNTPs at leisure. To reduce potential mutagenic effects from RNA incorporation, the presence of RNA within the genome is likely to be temporary, since it would be removed by specific proteins [59]. These types of effects could occur during general DNA metabolism, or be restricted to specific times during cell growth or for certain types of DNA repair, as suggested for non-homologous end-joining [53,60]. If this proposal is valid, then the observed ligation of nucleic acids with RNA upstream of DNA may be relevant to DNA metabolism and the physiological functions of T4Rnl1 and T4Rnl2 should include their potential to act as a ‘DNA repair’ protein, in addition to their role(s) as an RNA ligase.

Recently, nucleic acids have been identified to have a number of novel and unexpected roles in cellular metabolism [49,50]. The present study has identified that the nucleic acid ligases of T4 have the ability to join a variety of double-stranded substrates with similar efficiencies and, therefore, they have the potential to be involved in a variety of metabolic processes using different nucleic acids. To determine if such functions of the nucleic acid ligases may be physiologically significant, it will be necessary to have further systematic investigations into how the molecular aspects of the nucleic acids influence the activities of each protein. Such studies will need to be coupled with methodologies that allow detection of small amounts of RNA in genomes within cells.

Online Data

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Bowater (John Innes Centre, Norwich, U.K.) and Brian Jackson and Heather Sayer (both from University of East Anglia, Norwich, U.K.) for comments on this paper. We are grateful to Dr Borries Kemper for providing us with bacteriophage T4GT7 genomic DNA. This work was funded by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Quota studentship to D.R.B.

References

- 1.Miller E. S., Kutter E., Mosig G., Arisaka F., Kunisawa T., Ruger W. Bacteriophage T4 genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:86–156. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.86-156.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehman I. R. DNA ligase: structure, mechanism, and function. Science. 1974;186:790–797. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4166.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shuman S., Schwer B. RNA capping enzyme and DNA ligase: a superfamily of covalent nucleotidyl transferases. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;17:405–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson A., Day J., Bowater R. Bacterial DNA ligases. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1241–1248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty A. J., Suh S. W. Structural and mechanistic conservation in DNA ligases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4051–4058. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shuman S., Lima C. D. The polynucleotide ligase and RNA capping enzyme superfamily of covalent nucleotidyltransferases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomkinson A. E., Vijayakumar S., Pascal J. M., Ellenberger T. DNA ligases: structure, reaction mechanism, and function. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:687–699. doi: 10.1021/cr040498d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss B., Richardson C. C. Enzymatic breakage and joining of deoxyribonucleic acid, I. Repair of single-strand breaks in DNA by an enzyme system from Escherichia coli infected with T4 bacteriophage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1967;57:1021–1028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.4.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fareed G. C., Richardson C. C. Enzymatic breakage and joining of deoxyribonucleic acid. II. The structural gene for polynucleotide ligase in bacteriophage T4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1967;58:665–672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.2.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood W. B., Henninger M. Attachment of tail fibers in bacteriophage T4 assembly: some properties of the reaction in vitro and its genetic control. J. Mol. Biol. 1969;39:603–618. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood W. B., Conley M. P., Lyle H. L., Dickson R. C. Attachment of tail fibers in bacteriophage T4 assembly. Purification, properties, and site of action of the accessory protein coded by gene 63. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:2437–2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snopek T. J., Wood W. B., Conley M. P., Chen P., Cozzarelli N. R. Bacteriophage T4 RNA ligase is gene 63 product, the protein that promotes tail fiber attachment to the baseplate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1977;74:3355–3359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Runnels J. M., Soltis D., Hey T., Snyder L. Genetic and physiological studies of the role of the RNA ligase of bacteriophage T4. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;154:273–286. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amitsur M., Levitz R., Kaufmann G. Bacteriophage T4 anticodon nuclease, polynucleotide kinase and RNA ligase reprocess the host lysine tRNA. EMBO J. 1987;6:2499–2503. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho C. K., Shuman S. Bacteriophage T4 RNA ligase 2 (gp24.1) exemplifies a family of RNA ligases found in all phylogenetic domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:12709–12714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192184699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin S., Kiong Ho C., Miller E. S., Shuman S. Characterization of bacteriophage KVP40 and T4 RNA ligase 2. Virology. 2004;319:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherepanov A. V., De Vries S. Dynamic mechanism of nick recognition by DNA ligase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:5993–5999. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L. K., Ho C. K., Pei Y., Shuman S. Mutational analysis of bacteriophage T4 RNA ligase 1. Different functional groups are required for the nucleotidyl transfer and phosphodiester bond formation steps of the ligation reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:29454–29462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martins A., Shuman S. An RNA ligase from Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:50654–50661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins A., Shuman S. Characterization of a baculovirus enzyme with RNA ligase, polynucleotide 5′ kinase and polynucleotide 3′ phosphatase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:18220–18231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worthey E. A., Schnaufer A., Mian I. S., Stuart K., Salavati R. Comparative analysis of editosome proteins in trypanosomatids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6392–6408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart K. D., Schnaufer A., Ernst N. L., Panigrahi A. K. Complex management: RNA editing in trypanosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timson D. J., Singleton M. R., Wigley D. B. DNA ligases in the repair and replication of DNA. Mutat. Res. 2000;460:301–318. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho C. K., Wang L. K., Lima C. D., Shuman S. Structure and mechanism of RNA ligase. Structure. 2004;12:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omari K. E., Ren J., Bird L. E., Bona M. K., Klarmann G., LeGrice S. F. J., Stammers D. K. Molecular architecture and ligand recognition determinants for T4 RNA ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:1573–1579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pascal J. M., O'Brien P. J., Tomkinson A. E., Ellenberger T. Human DNA ligase I completely encircles and partially unwinds nicked DNA. Nature (London) 2004;432:473–478. doi: 10.1038/nature03082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sriskanda V., Shuman S. Specificity and fidelity of strand joining by Chlorella virus DNA ligase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3536–3541. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.15.3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekiguchi J., Shuman S. Ligation of RNA-containing duplexes by vaccinia DNA ligase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9073–9079. doi: 10.1021/bi970705m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nandakumar J., Shuman S. How an RNA ligase discriminates RNA versus DNA damage. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nandakumar J., Ho C. K., Lima C. D., Shuman S. RNA substrate specificity and structure-guided mutational analysis of bacteriophage T4 RNA ligase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:31337–31347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nandakumar J., Shuman S. Dual mechanisms whereby a broken RNA end assists the catalysis of its repair by T4 RNA ligase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23484–23489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins N. P., Cozzarelli N. R. DNA-joining enzymes: a review. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:50–71. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engler M. J., Richardson C. C. DNA ligases. In: Boyer P. D., editor. The Enzymes, vol. XV. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore M. J., Query C. C. Joining of RNAs by splinted ligation. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:109–123. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clepet C., Le Clainche I., Caboche M. Improved full-length cDNA production based on RNA tagging by T4 DNA ligase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuhn H., Frank-Kamenetskii M. D. Template-independent ligation of single-stranded DNA by T4 DNA ligase. FEBS J. 2005;272:5991–6000. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin S., Ho C. K., Shuman S. Structure–function analysis of T4 RNA ligase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17601–17608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkinson A., Sayer H., Bullard D., Smith A., Day J., Kieser T., Bowater R. NAD+-dependent DNA ligases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Streptomyces coelicolor. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 2003;51:321–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.10361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavesa-Curto M., Sayer H., Bullard D., MacDonald A., Wilkinson A., Smith A., Bowater L., Hemmings A., Bowater R. Characterisation of a temperature-sensitive DNA ligase from Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2004;150:4171–4180. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson A., Smith A., Bullard D., Lavesa-Curto M., Sayer H., Bonner A., Hemmings A. M., Bowater R. Analysis of ligation and DNA binding by Escherichia coli DNA ligase (LigA) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1749:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J., Russell D. W. 3rd edn. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Q. S., Unrau P. J. Purification of histidine-tagged T4 RNA ligase from E. coli. BioTechniques. 2002;33:1256–1260. doi: 10.2144/02336st03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cherepanov A. V., de Vries S. Kinetics and thermodynamics of nick sealing by T4 DNA ligase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:4315–4325. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blondal T., Hjorleifsdottir S. H., Fridjonsson O. F., Aevarsson A., Skirnisdottir S., Hermannsdottir A. G., Hreggvidsson G. O., Smith A. V., Kristjansson J. K. Discovery and characterization of a thermostable bacteriophage RNA ligase homologous to T4 RNA ligase 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:7247–7254. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blondal T., Thorisdottir A., Unnsteinsdottir U., Hjorleifsdottir S., Aevarsson A., Ernstsson S., Fridjonsson O. H., Skirnisdottir S., Wheat J. O., Hermannsdottir A. G., et al. Isolation and characterization of a thermostable RNA ligase 1 from a Thermus scotoductus bacteriophage TS2126 with good single-stranded DNA ligation properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:135–142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arabshahi A., Frey P. A. Standard free energy for the hydrolysis of adenylylated T4 DNA ligase and the apparent pKa of lysine 159. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8586–8588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keppetipola N., Shuman S. Characterization of a thermophilic ATP-dependent DNA ligase from the euryarchaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:6902–6908. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.6902-6908.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markham N. R., Zuker M. DINAMelt web server for nucleic acid melting prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W577–W581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bellacosa A., Moss E. G. RNA repair: damage control. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:R482–R484. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Begley T. J., Samson L. D. Molecular biology: a fix for RNA. Nature (London) 2003;421:795–796. doi: 10.1038/421795a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaufmann G. Anticodon nucleases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01525-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossi R., Montecucco A., Ciarrocchi G., Biamonti G. Functional characterization of the T4 DNA ligase: a new insight into the mechanism of action. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2106–2113. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.11.2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nick McElhinny S. A., Ramsden D. A. Polymerase mu is a DNA-directed DNA/RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2309–2315. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2309-2315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruiz J. F., Juarez R., Garcia-Diaz M., Terrados G., Picher A. J., Gonzalez-Barrera S., Fernandez de Henestrosa A. R., Blanco L. Lack of sugar discrimination by human Pol mu requires a single glycine residue. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4441–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Della M., Palmbos P. L., Tseng H. M., Tonkin L. M., Daley J. M., Topper L. M., Pitcher R. S., Tomkinson A. E., Wilson T. E., Doherty A. J. Mycobacterial Ku and ligase proteins constitute a two-component NHEJ repair machine. Science. 2004;306:683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1099824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pitcher R. S., Tonkin L. M., Green A. J., Doherty A. J. Domain structure of a NHEJ DNA repair ligase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bebenek K., Garcia-Diaz M., Patishall S. R., Kunkel T. A. Biochemical properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase IV. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20051–20058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kornberg A., Baker T. A. New York: Freeman; 1992. DNA Replication. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rydberg B., Game J. Excision of misincorporated ribonucleotides in DNA by RNase H (type 2) and FEN-1 in cell-free extracts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:16654–16659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262591699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pitcher R. S., Wilson T. E., Doherty A. J. New insights into NHEJ repair processes in prokaryotes. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:675–678. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.5.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.