Abstract

Stress stimuli can lead to remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton and subsequent alteration of cell adhesion and permeation as well as cell functions and cell fate. We investigated redox-dependent Rho GTPase-linked pathways controlling the actin cytoskeleton in the inner ear of the CBA mouse, by using aminoglycoside antibiotics as a noxious stimulus that causes loss of sensory cells via the formation of reactive oxygen species. Kanamycin treatment in vivo interfered with the formation of F-actin, disturbed the arrangement of β-actin in the stereocilia of outer hair cells, and altered the intermittent adherens junction/tight junction complexes between outer hair cells and supporting cells. The drug treatment also activated Rac1 and promoted the formation of the complex of Rac1 and p67phox while decreasing the activity of RhoA and reducing the formation of the RhoA/p140mDia complex. In inner-ear-derived cell lines, expression of mutated Rac1 changed the structural arrangement of F-actin and diminished the immunoreactivity of p140mDia. These findings suggest that actin depolymerization induced by kanamycin is mediated by Rac1 activation, followed by the formation of superoxide by NADPH oxidase. These changes will ultimately contribute to aminoglycoside-induced loss of hair cells.

Keywords: cytoskeleton, Rho GTPases, p67phox, p140mDia, kanamycin

The orderly assembly and disassembly of actin represent a major component of cellular homeostasis. Once the actin cytoskeleton is disturbed by stress stimuli, such as noise trauma, drug treatment, and possibly aging, cell adhesion and permeability are altered, function is compromised, and cells may enter into apoptosis. In the inner ear, the structural integrity of the cytoskeleton of the organ of Corti is a prerequisite for our ability to process acoustic information. Although the control mechanisms maintaining the actin cytoskeleton in the auditory sensory cells are of utmost importance, they are still poorly understood.

In all eukaryotic cells, small Rho GTPases, a large subfamily of the Ras superfamily of GTPases, are key regulators of the actin cytoskeleton. Among the Rho GTPases, Rac, Cdc42, and RhoA play crucial roles in cellular processes such as polarization, cell–cell and cell–matrix adhesion, membrane trafficking, cytoskeletal and transcriptional regulation, and cell proliferation (Hall, 1998a,b; Burridge and Wennerberg, 2004). The three distinct mammalian Rac isoforms (Rac1, Rac2, and Rac3) that are encoded by different genes share between 89% and 93% identity in their amino acid sequences (Haataja et al., 1997; Wherlock and Mellor, 2002) and stimulate formation of lamellipodia and membrane ruffles. Rac1 is widespread, whereas Rac2 and Rac3 are largely restricted to hematopoietic and neural tissues, respectively (Burridge and Wennerberg, 2004). In addition, Rac1 and Rac2 activate the NADPH oxidase complex, which promotes the formation of superoxide (Nimnual et al., 2003; Takeya and Sumimoto, 2003; Sarfstein et al., 2004), which in turn may inhibit the activity of RhoA (Caron, 2003).

RhoA regulates F-actin formation and focal adhesions via its downstream effectors, such as the mammalian homolog of diaphanous, mDia (Watanabe et al., 1999). Interestingly, p140mDia is a homolog of the human deafness gene, DFNA1 (in the mouse named p140mDia or Dia1), which is a profilin ligand, a target of Rho, and a regulator of the polymerization of actin (Lynch et al., 1997). In the inner ear, Rho GTPases may mediate hair cell development and stereocilia morphogenesis (Kollmar, 1999) and may modulate outer hair cell motility (Kalinec et al., 2000). Furthermore, inhibition of Rho GTPase activity can rescue auditory hair cells from aminoglycoside toxicity (Bodmer et al., 2002).

The adverse reactions of aminoglycosides to the inner ear have been linked to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS; Forge and Schacht, 2000), which, in turn, can affect the structure and architecture of cells, eventually leading to cell death. This study investigates redox-dependent Rho GTPase-associated pathways that control actin cytoskeletal rearrangements in the inner ear of CBA/J mice following treatment with kanamycin. Additionally, we examine the role of Rac1 in the control of the actin cytoskeleton by using an immorto-mouse-derived inner ear cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Kanamycin sulfate was purchased from USB Corporation (Cleveland, OH; catalog No. 17924, lot No. 110755); ECL for Western blotting detection reagents from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). BenchMark Protein (molecular weight standards for Western blot assays) was purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA); primary antibodies such as monoclonal anti-Rac1 were from Upstate (Waltham, MA); monoclonal mouse anti-p67phox and anti-p140mDia were from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, CA); monoclonal anti-β-actin and anti-c-Myc antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); and polyclonal rabbit anti-RhoA was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies for Western blotting were obtained from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). F-actin was stained with Alexa 488 phalloidin and nuclei with propidium iodide (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Complete Mini EDTA free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets were from Roche Diagnostic GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis Kit was purchased from Invitrogen. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Plasmid Construction

We constructed pCMV-Rac1T17N and pCMV-Rac 1Q61L plasmids (Jackson et al., 2003) in N-terminal Myc-tagged expression vectors (BD Biosciences Clontech). The Rac1 coding sequence was amplified by PCR with two EcoRI/XhoI linker primer pairs (Integrated DNA Technology, Loralville, IA), 5′-GAATTCTGCAGGCCATCAAG-3′ and 5′-CTCGAGTTACAACAGCAGGC-3′. The PCR product was ligated into pGEM-T easy vector (Sigma-Aldrich), digested with EcoR/XhoI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA), and subcloned in-frame into the BamHI/XhoI sites of the CMV-driven N-terminal Myc epitope-tagged pCMV-Myc mammalian expression vector. A dominant negative plasmid pCMV-Rac1T17N and constitutively active plasmid pCMV-Rac1Q61L were generated by using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The integrity of all constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing (University of Michigan DNA Core).

Animals and Drug Administration

Male CBA mice (4 weeks of age; Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) had free access to water and a regular mouse diet (Purina 5025; Purina, St. Louis, MO) and were acclimated for 1 week before the experiments. All research protocols were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals. Animal care was under the supervision of the University of Michigan’s Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine. Mice received subcutaneous injections of kanamycin (700 mg kanamycin base/kg body weight twice daily) for 3, 7, or 11 days as indicated in the figure legends; control mice received saline injections; an additional control group remained untreated. The number of animals associated with each treatment is given in the legends to the figures. The animals were sacrificed 3 hr after the last injection, and the cochleae were removed for further processing.

Cell Culture and Transfections

HEI-OC1 cells (Kalinec et al., 2003; obtained from Dr. F. Kalinec, House Ear Institute, Los Angeles, CA) were plated on 100-mm Falcon Primeria plates in 8–10 ml of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 μg of γ-interferon/L (to promote conditional immortality), without antibiotics or antifungal agents. The cells were allowed to proliferate in an incubator at 10% CO2 at 33°C. When the cultures reached 70–80% confluence, they were transfected with Lipo-Fectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as directed by the manufacturer. After 24 hr of transfection, cells were fixed for 30 min at 4°C for immunocytochemistry.

Extraction of Total Protein

The cochleae were rapidly removed and dissected in ice-cold 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS). One cochlea (including organ of Corti, lateral wall tissues, and modiolar portion of the VIIIth nerve) was homogenized in an ice-cold RIPA buffer (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY; catalog No. 20–188) by using a Micro-Tissue Grind pestle for 30 sec. For immunoprecipitation assays, 10 μl each of phosphatase inhibitor cocktail I and II (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to 1 ml RIPA buffer. After 15 min on ice, the homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000g at 4°C for 10 min.

Pulldown Assay

Mice were decapitated by cervical dislocation, and cochleae were rapidly removed from the temporal bone and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Six cochleae from three mice were pooled for each group and homogenized in RIPA buffer with a Tissue Tearor for 30 sec on ice. After centrifugation at 15,000g at 4°C for 10 min, the supernatant was retained. After detection of protein concentration, 800 μg of each sample was used for a pulldown assay with a Rac1 and RhoA activation kit (Stressgen, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada).

Immunoprecipitation

Mixtures of total cochlear protein (300 μg) with 0.25 μg of the control IgG (mouse IgG) and 20 μl of agarose conjugate protein A + G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were incubated at 4°C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 1,000g for 30 sec at 4°C, the supernatant was incubated with monoclonal mouse anti-Rac1 or polyclonal rabbit anti-RhoA (2 μg) for 6 hr at 4°C. Agarose conjugate (20 μl) protein A + G was added, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C on a rotating device overnight. The pellets were collected by centrifugation at 1,000g for 1 min at 4°C and washed three times with RIPA buffer. After the final wash, the pellets were resuspended in 40 μl of 2× electrophoresis sample buffer. Subsequently, monoclonal mouse anti-p67phox (1:500) or mouse anti-p140mDia (1:1,000) antibodies were used for Western blotting.

Western Blot Analysis

The protein samples (50 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE (10% for detection of p67phox and β-actin, 6% for detection of p140mDia, and 13% for detection of Rac1 and RhoA). After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences), and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T). The membranes were incubated with mouse anti-Rac1 (1:2000), mouse anti-p67phox (1:500), rabbit anti-RhoA (1:500), or mouse anti-p140mDia (1:1,000) antibody for 2 hr, then washed three times (10 min each) with PBS-T. Membranes were incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody at a concentration of 1:10,000 for 1 hr. After extensive washing of the membrane, the immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The membranes were then stripped and restained for anti-GAPDH at a concentration of 1:20,000 as a control for sample loading.

Immunocytochemistry

Mice were decapitated and the temporal bones quickly removed. Cochleae were fixed immediately by slowly perfusing cold 4% paraformaldehyde from a syringe through the round window to an exit hole created in the apex. Cochleae remained in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. After decalcification with 4% EDTA, pH 7.4, for 48 hr at 4°C, cochleae were dissected under a microscope, and the cochlear sensory epithelium was removed. The sensory epithelium was then incubated in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, and blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with anti-β-actin at a concentration of 1:2,000 in darkness at 4°C for 72 hr. After being washed three times (10 min each), the tissues were incubated with the secondary antibody (Alexa 488 conjugated) at a concentration of 1:500 at 4°C overnight in darkness. For F-actin staining, sensory epithelia were incubated with Alexa 488 phalloidin at a concentration of 5 μg/ml at room temperature in darkness for 1 hr. After three washes, epithelia were incubated with propidium iodide (1 μg/ml in PBS) at room temperature for 30 min. After the final wash with PBS, the epithelia were mounted on slides. Control incubations were routinely processed without primary antibody. Immunolabeling was imaged by using a Zeiss laser confocal microscope.

Electron Microscopy

Two mice were randomly chosen from the saline- and kanamycin- treated groups after 11 days of treatment, and, after opening of the auditory bullae, the cochleae were immediately fixed with cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS at 4°C for 4 hr. The auditory bullae were decalcified in 4.13% EDTA, pH 7.3, for 3 days at 4°C. After washes in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, the tissue was post-fixed in 1% OsO4 for 1.5 hr at room temperature, dehydrated to 70% ethanol, then stained with saturated uranyl acetate in 70% ethanol before further dehydration and embedding in plastic resin. The entire bulla was embedded. Sections parallel to the cochlear modiolus were cut at six to eight levels through the intact cochlea. At each level, a series of 1-μm sections was collected and stained with toluidine blue for light microscopic examination. At each of the levels, a series of thin sections for electron microscopy was also collected. Some of the sections were mounted on formvar-coated single-slot grids to allow uninterrupted views of the section of the whole cochlea for an assessment of almost the entire length of the organ of Corti. Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and all thin sections were examined in a Jeol 1010 transmission electron microscope. Photographic negatives of the micrographs were digitized on a flatbed scanner and the images imported into Adobe Photoshop. The digital images were processed to obtain contrast reversal and optimal contrast and brightness.

Statistical Analysis

Results reported are generally representative of at least three independent replications, as indicated in the figure legends. When appropriate, data were statistically evaluated by Student’s t-test and by analyses of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls test for significance (P < 0.05), using Primer of Biostatistics software (McGraw-Hill Software, New York, NY).

RESULTS

Kanamycin Inhibits F-Actin Formation and Perturbs β-Actin in the Stereocilia of Outer Hair Cells

The drug treatment mirrored our previously established adult CBA mouse model of aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss (Wu et al., 2001), in which progressive damage of hair cells and compromised auditory function can be achieved with injections of 700 mg kanamycin base/kg body weight bid. A 7-day regimen will not yet significantly affect auditory function, whereas continued injections will lead to a severe loss of sensory cells and function by 14 days (Jiang et al., 2005).

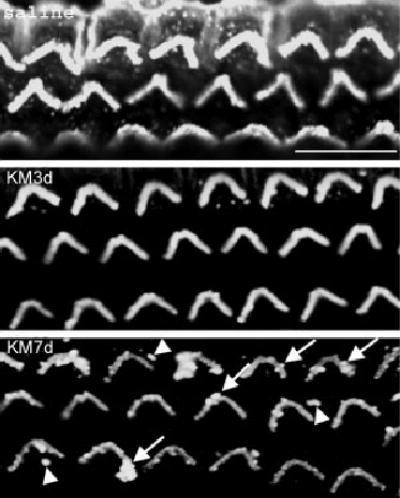

Control mice treated with saline for 7 days and stained for F-actin showed a well-defined outline of outer hair cells (Fig. 1, saline; cuticular plate level) and parallel lines in the phalanges of Deiters cells (nuclear level, arrowheads). After treatment with kanamycin for 3 days, the phalanges of Deiters cells became somewhat disorganized (Fig. 1, KM3d) but there was no apparent change in the arrangement of actin at the cuticular plate level of outer hair cells. After 7 days of kanamycin treatment, F-actin of outer hair cells showed signs of disturbance, and some stereocilia were disorderly or missing (Fig. 1, KM7d, arrows). Phalanges of Deiters cells became detached from the cell body and formed a loose ring around hair cells (Fig. 1, KM7d, stars).

Fig. 1.

Kanamycin disrupts F-actin arrangements in vivo. Surface preparations from the basal turn of the organ of Corti were stained with phalloidin (green, for F-actin) and propidium iodide (red, for nuclei). In the saline-treated mouse cochlea (top, saline), staining for F-actin showed a well-defined outline of outer hair cells (cuticular plate level) and a regular arrangement at the phalanges of Deiters cells (nuclear level, arrowhead). After treatment with kanamycin for 3 days (KM3d), there were no obvious changes in F-actin at the cuticular plate level of outer hair cells, but phalanges of Deiters cells had become disorganized. After 7 days of treatment (KM7d), F-actin of outer hair cells was disturbed, and stereocilia were disorderly or missing (arrows). Phalanges of Deiters cells became detached from the cell body and formed a loose ring around hair cells (stars). This figure represents three mice from each group. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Next, we analyzed β-actin in the cochlea and its localization after kanamycin treatment in vivo. The total amount of β-actin in cochlear homogenates did not change after 7 days of kanamycin treatment (Western blotting; data not shown), but immunohistochemistry on surface preparations of the organ of Corti demonstrated a decrease in β-actin and small changes in its arrangement in the stereocilia (Fig. 2, KM7d, arrows and arrowheads, respectively). These two experiments demonstrate a disturbance of the actin cytoskeleton in the early phases of in vivo aminoglycoside intoxication, when no functional consequences are evident.

Fig. 2.

Kanamycin changes the organization of β-actin in stereocilia of outer hair cells. Immunostaining of β-actin was decreased in stereocilia of outer hair cells by kanamycin treatment (KM3d and KM7d) compared with saline control animals (saline). The β-actin formed blobs in the stereocilia (KM7d, arrows), and parts were dissociated from the stereocilia (KM7d, arrowheads). Preparations are from the basal turn of the organ of Corti. This figure represents three mice from each group. Scale bar = 10 μm.

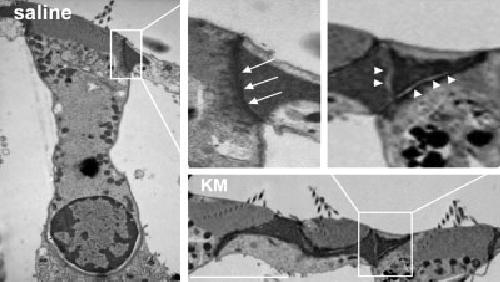

Intermittent Adherens Junction/Tight Junction Complexes Are Disturbed by Kanamycin

We examined the intermittent adherens junction/tight junction complex between outer hair cells and the phalangeal processes of Deiters cells by electron microscopy. In saline-treated mice, intermittent adherens junction/tight junction complexes were compact and dense (Fig. 3, saline; arrows in enlargement). However, after injection of kanamycin for 11 days, the junctions widened and became less dense (Fig. 3, KM; arrowhead in enlargement).

Fig. 3.

Kanamycin disturbs intermittent adherens junction/tight junction complexes. Electron microscopy indicates that intermittent adherens junction/tight junction complexes were compact and had high densities, composed mainly of actin, in saline control animals (arrows). After kanamycin treatment for 10 days, the junctions lost the close contact between cells (arrowheads). This figure represents two mice from each group, and the sections are from the basal turn of the organ of Corti. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Kanamycin Increases Rac1 Activity and Promotes NADPH Oxidase Via Rac1

Mammalian Rac1 and Rac2 activate the NADPH oxidase complex, which promotes the formation of ROS (Nimnual et al., 2003; Sarfstein et al., 2004). Because aminoglycosides stimulate ROS formation, we investigated whether Rac activation could be responsible for ROS formation by aminoglycosides (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Kanamycin increases Rac1 activity and the Rac1/p67phox complex in vivo. A: Increased Rac1 activity. Active Rac1 bound to GTP (Rac1-GTP) in cochlear tissue was measured by a pulldown assay and detected by immunoblot with an anti-Rac1 antibody. Total Rac1 was detected by direct immunoblot with anti-Rac1 antibody. Rac1-GTP increased after treatment with kanamycin. Total Rac1 (active plus inactive) did not change among the groups. B: Increased formation of a complex of Rac1 and p67phox. Complexes of Rac1-p67phox in cochlear protein were detected by immunoprecipitation with antibody to Rac1, followed by immunoblot with antibody to p67phox. Total p67phox was detected by direct immunoblot. Kanamycin treatment did not change the level of total p67phox but increased the formation of the Rac1-p67phox complex. N, tissue sample from a normal untreated mouse cochlea; S, saline-treated cochlea; KM3d, KM7d, kanamycin treatment for 3 and 7 days, respectively. This figure is representative of three repetitions for immunoprecipitation assays and four repetitions for total Rac1 and p67phox by Western blot.

Total Rac1 was determined by direct immunoblot with anti-Rac1 antibody and did not change among the treatment groups. Active Rac1 bound to GTP (GTP-Rac1) was first isolated from cochlear homogenates by a pulldown assay and then detected by immunoblot with anti-Rac1 antibodies. Active GTP-Rac1 increased significantly after kanamycin treatment.

We next analyzed for Rac1-p67phox complexes by immunoprecipitating Rac1 from cochlear proteins and immunoblotting against p67phox. Kanamycin treatment increased the formation of Rac1-p67phox (Fig. 4B) but did not change the level of total p67phox, detected by a direct immunoblot. These results indicate that kanamycin can activate NADPH oxidase via GTP-Rac1.

Kanamycin Decreases Active RhoA and Also Down-Regulates RhoA Effector p140mDia

RhoA promotes myosin contractility, and the resulting tension drives the assembly of F-actins and focal adhesions (Amano et al., 1996; Riveline et al., 2001). RhoA-controlled F-actin formation and focal adhesions can also be induced by coexpression of activated forms of the mammalian homolog of diaphanous (mDia), another Rho effector (Watanabe et al., 1999). Excess formation of ROS, either by aminoglycosides directly or via the activation of NADPH oxidase, would inhibit the activity of RhoA.

A pulldown assay was used to detect active RhoA (GTP-RhoA) from cochlear protein homogenates. Protein levels of GTP-RhoA and total RhoA were reduced by kanamycin treatment (Fig. 5A). Consistently with the decrease of the active RhoA, the complex of RhoA and p140mDia and total p140mDia also declined (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Kanamycin decreases RhoA activity and the RhoA/p140mDia complex in vivo. A: Decreased activity of RhoA. Active RhoA bound to GTP (RhoA-GTP) in cochlear tissue was measured by a pulldown assay and detected by immunoblot with anti-RhoA antibody. Total RhoA was detected by direct immunoblot with an anti-RhoA antibody. RhoA-GTP decreased dramatically after treatment with kanamycin compared with normal and saline-treated samples. Total RhoA (active plus inactive) did not change among the groups. B: Decreased formation of complex between RhoA and p140mDia. Complexes of RhoA-p140mDia in cochlear protein were detected by immunoprecipitation with antibody to RhoA, followed by immunoblot with an antibody to p140mDia. Total p140mDia was detected by direct immunoblot. Kanamycin decreased the level of total p140mDia and also decreased formation of the complex of RhoA-p140mDia. N, tissue sample from a normal untreated mouse cochlea; S, saline-treated cochlear sample; KM3d, KM7d, kanamycin treatment for 3 and 7 days, respectively. This figure is representative of three repetitions for immunoprecipitation assay and four for total RhoA and p140mDia by Western blot.

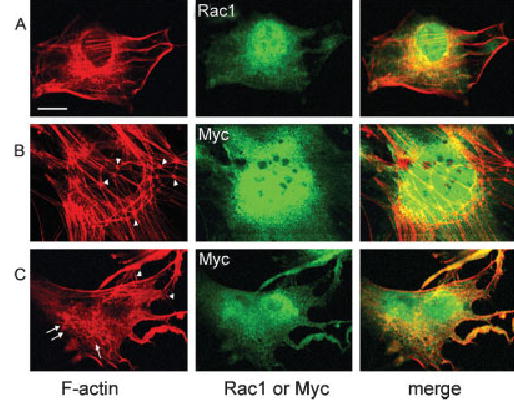

Rac1 Controls Formation of F-Actin and Regulates p140mDia Deafness Gene in an Inner Ear Cell Line

To probe direct relationships between Rac1 and F-actin formation and between active Rac1 and p140m Dia, we tested mutations of the Rac1 gene by transfecting Rac1T17N (dominant negative) or Rac1Q61L (constitutively active) into an HEI-OC1 cell line (Fig. 6A). This cell line is derived from cells of the inner ear and expresses characteristics of hair cells (Kalinec et al., 2003). Rac1T17N stimulated formation of knot-like structures of F-actin (Fig. 6B, arrowheads), but actin foci were not found. In contrast, Rac1Q61L resulted in formation of actin foci (Fig. 6C, arrows) as well as structures resembling lamellipodia (Fig. 6C, arrowheads).

Fig. 6.

Mutation of Rac1 changes the formation of F-actin in the HEI-OC1 cell line. Rac1T17N and Rac1Q61L were transfected into an HEI-OC1 cell line. Expressions of Rac1T17N and Rac1Q61L were determined by staining with an anti-Myc antibody (green), and endogenous Rac1 was detected with an anti-Rac1 antibody (green). F-actin (red) was stained with phalloidin. Normal control cells (A) showed strong staining of F-actin and Rac1. Transfection with Rac1T17N stimulated the formation of knot-like structures of F-actin (B, arrowheads), but lamellipodia and actin foci were not found. Transfection with Rac1Q61L resulted in formation of actin foci (C, arrow) as well as lamellipodia (C, arrowheads). Both normal and mutated Rac1 and F-actin colocalized (merge, yellow color). This figure represents three individual experiments. Scale bar = 10 μm.

p140mDia was also analyzed following transfection of the constitutively active Rac1Q61L into the HEI-OC1 cell line. Immunoreactivity for p140mDia colocalized with F-actin in control cells (Fig. 7A, merge, yellow). However, staining for p140mDia disappeared almost completely in transfected cells (Fig. 7B, green). The results suggest that mutations of Rac interfere with actin filament formation in vitro and connect well with the observations that activation of Rac1 leads to disruption of actin in vivo.

Fig. 7.

A constitutively active Rac1 mutation reduces immunoreactivity of p140mDia in the HEI-OC1 cell line. Rac1Q61L was transfected into an HEI-OC1 cell line. Endogenous p140mDia was detected with an anti-p140mDia antibody (green), and F-actin was stained with phalloidin (red). In control cultured cells (A), immunostaining for p140mDia was evident and it colocalized with F-actin (A, merge, yellow). In contrast, staining for p140mDia dramatically decreased in cells transfected with constitutively active Rac1 (B, p140mDia, green). This figure represents three individual experiments. Scale bar = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that disruptions of the actin cytoskeleton induced by kanamycin in cochlear sensory cells are mediated by Rac1 activation and the formation of superoxide by NADPH oxidase. Free radicals may then affect the RhoA/p140mDia gene pathway regulating actin and affect cell survival and apoptotic pathways, ultimately resulting in loss of hair cells.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics catalyze the formation of ROS both in vitro and in vivo (Forge and Schacht, 2000). In vitro, the drugs can complex with transition metals and abstract electrons from donors, such as unsaturated fatty acids, to produce ROS nonenzymatically (Lesniak et al., 2005). In vivo, this nonenzymatic action may be complemented by ROS formation via NADPH oxidase, insofar as activated Rac can bind to the p47phox or p67phox proteins of the NADPH oxidase complex, leading to its activation (Takeya and Sumimoto, 2003; Takeya et al., 2003). As the current study shows, kanamycin indeed increases the formation of a complex between active Rac1 and p67phox kanamycin in vivo. ROS have been causally linked to the toxic actions of aminoglycosides by the observation that free radical scavengers prevent aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss (Song et al., 1997, 1998; Sha and Schacht, 1999; Kalinec et al., 2003). In particular, superoxide radicals appear to be involved, because mice overexpressing superoxide dismutase are protected from the functional and morphological detriments of aminoglycosides (Sha et al., 2001). Furthermore, the notion that activation of Rac1 mediates ototoxicity is supported by the observation that Clostridium difficile toxin B, a broad-spectrum inhibitor of small GTPases, protects auditory hair cells from aminoglycosides (Bodmer et al., 2002).

As an antagonist of Rac1, Rho stimulates the assembly of F-actins and adhesion complexes (Schmidt and Hall, 1998). This process relies on the downstream effector Rho-kinase (ROCK) and myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation (Chrzanowska-Wodnicka and Burridge, 1996; Kimura et al., 1996). RhoA promotes myosin contractility, and the resulting tension drives the assembly of stress fibers and focal adhesions (Amano et al., 1996; Riveline et al., 2001). Active GTP-RhoA and total RhoA were reduced by kanamycin treatment in the cochlea, affecting the mechanisms responsible for the maintenance of structural integrity and rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton (Schmidt and Hall, 1998). The decrease in RhoA activity is consistent with the stimulation of Rac1 and NADPH oxidase activity leading to the formation of superoxide and other ROS that inactivate RhoA. RhoA-controlled stress fiber formation and focal adhesions can also be induced by coexpression of activated forms of the mammalian homolog of diaphanous (mDia), another Rho effector (Watanabe et al., 1999). p140mDia is a homolog of the human deafness gene DFNA1 (in the mouse named p140mDia or Dia1), which is a profilin ligand, a target of Rho, and a regulator of the polymerization of actin (Lynch et al., 1997). The decrease of p140mDia after kanamycin treatment is consistent with a decreased expression of the gene, although other explanations (e.g., increased protein degradation) cannot be ruled out.

Aminoglycoside-induced loss of auditory sensory cells proceeds slowly in vivo, taking weeks of drug treatment. Morphological changes seen in the current study are in good agreement with our general understanding of aminoglycoside actions. Structural rearrangements, including loss of membrane integrity and loss of F-actin, accompany cell death in the avian cochlea (Mangiardi et al., 2004). Freeze fracture studies of gentamicin effects show marked morphological abnormalities in the junctions between supporting cells of the guinea pig organ of Corti (McDowell et al., 1989). Gentamicin also abolishes gap junctional coupling in Hensen cells in vitro (Todt et al., 1999), probably via ROS, insofar as radical scavengers can protect gap junctional function. As shown here, aminoglycosides promote actin depolymerization and disturb intermittent adherens junction/tight junction complexes, causing retractions of the lamellae and rounding of the cell body, perhaps by inhibition of RhoA and p140mDia. In the organ of Corti, intermittent adherens junction/tight junction complexes mediate intercellular communication and maintain the surface tension of the reticular lamina. A disruption of this organization would lead to both morphological and functional damage, as is associated with aminoglycoside ototoxicity.

It is noteworthy that the effects on both the small GTPase pathway and the actin cytoskeleton precede the functional deficits and the loss of sensory cells induced by aminoglycosides. After 3 days of treatment, and more obviously after 7 days, changes in the GTPase pathway and the actin cytoskeleton become evident. Likewise, Rac1 activity increases at an early phase (3 days) of treatment with kanamycin. In contrast, by 3 and 7 days, there are no measurable functional deficits or loss of hair cells in this model (Jiang et al., 2005). These events therefore are early steps in the toxic cascade of ototoxicity.

Although the in vivo data suggest a link between the disruption of the actin cytoskeleton following kanamycin treatment and Rho-GTPases, the studies in the cell line directly demonstrate the influence of the Rac1 pathway on the actin cytoskeleton. A Rac1T17N mutation stimulated the formation of knot-like structures of F-actin; Rac1Q61L resulted in formation of actin foci and lamellipodia, reducing F-actin and, in addition, reducing the levels of p140mDia.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that actin cytoskeletal disruptions induced by aminoglycosides depend on the Rac/ROS/Rho pathway. Aminoglycoside antibiotics, beginning with the activation of Rac1 and NADPH-mediated changes in the cellular redox state, disturb the cascade of small GTPases that control the rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton. These changes in homeostatic and apoptotic pathways will ultimately result in the loss of hair cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Andrew Forge, London, for Figure 3 and for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This first two authors contributed equally to this work.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health; Contract grant number: R01 DC-03685; Contract grant number: P30 DC-05188.

Hongyan Jiang’s current address is Otorhinolaryngology Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510080, People’s Republic of China.

References

- Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer D, Brors D, Pak K, Gloddek B, Ryan A. Rescue of auditory hair cells from aminoglycoside toxicity by Clostridium difficile toxin B, an inhibitor of the small GTPases Rho/Rac/Cdc42. Hear Res. 2002;172:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Wennerberg K. Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell. 2004;116:167–179. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E. Rac signalling: a radical view. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:185–187. doi: 10.1038/ncb0303-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Burridge K. Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of F-actins and focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1403–1415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Schacht J. Aminoglycoside antibiotics. Audiol Neurootol. 2000;5:3–22. doi: 10.1159/000013861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haataja L, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N. Characterization of RAC3, a novel member of the Rho family. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20384–20388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998a;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. G proteins and small GTPases: distant relatives keep in touch. Science. 1998b;280:2074–2075. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson TA, Koterwas DM, Morgan MA, Bradford AP. Fibroblast growth factors regulate prolactin transcription via an atypical Rac-dependent signaling pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1921–1930. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Sha SH, Schacht J. The NF-κB pathway protects cochlear hair cells from aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:644–651. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec F, Zhang M, Urrutia R, Kalinec G. Rho GTPases mediate the regulation of cochlear outer hair cell motility by acetylcholine. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28000–28005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec GM, Webster P, Lim DJ, Kalinec F. A cochlear cell line as an in vitro system for drug ototoxicity screening. Audiol Neurootol. 2003;8:177–189. doi: 10.1159/000071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Ito M, Amano M, Chihara K, Fukata Y, Nakafuku M, Yamamori B, Feng J, Nakano T, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Science. 1996;273:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollmar R. Who does the hair cell’s “do”? Rho GTPases and hair-bundle morphogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:394–398. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)80059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesniak W, Pecoraro VL, Schacht J. Ternary complexes of gentamicin with iron and lipid catalyze formation of reactive oxygen species. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:357–364. doi: 10.1021/tx0496946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch ED, Lee MK, Morrow JE, Welsh PL, Leon PE, King MC. Nonsyndromic deafness DFNA1 associated with mutation of a human homolog of the Drosophila gene diaphanous. Science. 1997;278:1315–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiardi DA, McLaughlin-Williamson K, May KE, Messana EP, Mountain DC, Cotanche DA. Progression of hair cell ejection and molecular markers of apoptosis in the avian cochlea following gentamicin treatment. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475:1–18. doi: 10.1002/cne.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell B, Davoes S, Forge A. The effect of gentamicin-induced hair cell loss on the tight junctions of the reticular lamina. Hear Res. 1989;40:221–232. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimnual AS, Taylor LJ, Bar-Sagi D. Redox-dependent downregulation of Rho by Rac. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:236–241. doi: 10.1038/ncb938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Kam Z, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD. Focal contacts as mechano-sensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1175–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarfstein R, Gorzalczany Y, Mizrahi A, Berdichevsky Y, Molshanski-Mor S, Weinbaum C, Hirshberg M, Dagher MC, Pick E. Dual role of Rac in the assembly of NADPH oxidase: tethering to the membrane and activation of p67phox. A study based on mutagenesis of p67 phox-Rac1 chimeras. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16007–16016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Hall MN. Signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:305–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha SH, Schacht J. Salicylate attenuates gentamicin-induced ototoxicity. Lab Invest. 1999;79:807–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha SH, Zajic G, Epstein CJ, Schacht J. Overexpression of copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase protects from kanamycin-induced hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol. 2001;6:117–123. doi: 10.1159/000046818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song BB, Anderson DJ, Schacht J. Protection from gentamicin ototoxicity by iron chelators in guinea pig in vivo. J. Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:369–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song BB, Sha SH, Schacht J. Iron chelators protect from aminoglycoside-induced cochleo- and vestibulo-toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:189–195. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeya R, Sumimoto H. Molecular mechanism for activation of superoxide-producing NADPH oxidases. Mol Cells. 2003;16:271–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeya R, Ueno N, Kami K, Taura M, Kohjima M, Izaki T, Nunoi H, Sumimoto H. Novel human homologues of p47phox and p67phox participate in activation of superoxide-producing NADPH oxidases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25234–25246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todt I, Ngezahayo A, Ernst A, Kolb HA. Inhibition of gap junctional coupling in cochlear supporting cells by gentamicin. Pflugers Arch. 1999;438:865–867. doi: 10.1007/s004249900109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Kato T, Fujita A, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S. Cooperation between mDia1 and ROCK in Rho-induced actin reorganization. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:136–143. doi: 10.1038/11056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherlock M, Mellor H. The Rho GTPase family: A Racs to Wrchs story. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:239–240. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WJ, Sha SH, McLaren JD, Kawamoto K, Raphael Y, Schacht J. Aminoglycoside ototoxicity in adult CBA, C57BL and BALB mice and the Sprague-Dawley rat. Hear Res. 2001;158:165–178. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]