An expanding literature base indicates the incidence and prevalence of emotional/behavioral problems in young children is increasing. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' (DHHS') 1999 report, Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General, estimates that at least one in five (20%) children and adolescents has a mental health disorder at some point in their life from childhood to adolescence.1 At least one in 10 (10%), or about 6 million people, has a serious emotional disturbance at some point in their life.1

On October 23–24, 2000, DHHS convened a multidisciplinary group of experts from fields including mental health, public health, and epidemiology. The group advised, “It is essential that the nation find ways to support emotional health of our youngest children and their families through a continuum of comprehensive, individualized, culturally competent services that focus on promotion, prevention, and intervention.” They also recommended steps to ensure the emotional health of infants not only to address school readiness, but to help families be stronger, supportive teachers for their children.

Research highlights the importance of the first three years of life for school readiness, but also the important role that emotional health plays in preparing children to engage in cognitive tasks.2–5 Before there is thought and language, there is emotion, and it is this early affect within the context of the earliest relationships that forms the basis for all future development.6–8 Research has also shown that the emergence of early onset emotional/behavioral problems in young children is related to a variety of health and behavior problems in adolescence, not to mention juvenile delinquency, school drop out, etc.9–11

Families and communities, working together, can help children with mental disorders. A broad range of services is often necessary to meet the needs of these children and their families. However, in many communities, services for young people with serious emotional disturbances are unavailable, unaffordable, or inappropriate. An estimated two-thirds of the young people who need mental health services in the United States are not receiving them.1 As a result, many children with mental health issues become involved with the juvenile justice system and sometimes parents give up custody of their own children in order to obtain services for them.1

Estimating the prevalence of emotional/behavioral disorders in children is critical to providing the mental health services they need. This is extremely difficult, however, given the lack of a “standard” and correct inclusive definition for a minimum functional level of impairment in some or all domains for an agreed-upon duration. These challenges are at the heart of the problem for public health care workers and other professionals attempting to offer young children and their families the proper mental health supports and services.

A literature review revealed that estimates of the number of children suffering from serious emotional/behavioral problems vary significantly depending on study purpose, methodology for selection of study population, and criteria used to diagnoses disorders and identify functional impairment. These wide variations highlight a huge challenge in early childhood mental health. There are many reasons for underreporting that need immediate attention. For example, establishing a standard definition of “serious emotional disturbance” and an agreed-upon minimum level of functional limitation in certain domains to establish a “case” would help eliminate the underreporting of serious emotional disturbance in very young children.

CHALLENGES

The term “serious emotional disturbance” refers to a diagnosed mental health problem that substantially disrupts a child's ability to function socially, academically, and emotionally. It is not a formal DSM-IV diagnosis, but rather an administrative term used by state and federal agencies to identify a population of children who have significant emotional and behavioral problems and who have a high need for services. The official definition of children who have serious emotional disturbance adopted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) refers to “persons from birth up to age 18 who currently or at any time during the past year had a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder of sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria specified within the DSM-III-R, and that resulted in functional impairment which substantially interferes with or limits the child's role or functioning in family, school, or community activities (SAMHSA, 1993, this definition is also used with newer diagnostic systems such as DSM-IV). The term does not signify any particular diagnosis per se; rather, it is a legal term that triggers a host of mandated services to meet the needs of these children.”12

The epidemiology of mental disorders varies according to which definition of “caseness” is used. For this article, “case” is an epidemiological term for someone who meets the criteria for a disease or disorder, or who is at-risk. Efforts are underway in the epidemiology of mental disorders to establish an agreed-upon minimum level of functional limitation required to establish a “case.” It is sometimes difficult to determine when a set of symptoms proceeds to the level of a mental disorder. In many instances, symptoms are not of sufficient severity or duration in certain domains to meet criteria for a disorder and that may differ from culture to culture.

The underutilization of supports and services by families of children with emotional/behavioral disturbances also contributes to underestimated prevalence. Families may underutilize supports and services because they are unsure if their child's behavior is sufficiently different from other children to require help. They may realize the child's behavior needs professional attention, but may avoid treatment because it is painful or frightening, or they may regard it as a personal failure. They may fear their child will be inappropriately labeled, or they may be experiencing anger about the blame that continues to be placed on families with emotionally disturbed children. The perceived stigma of mental health care can also interfere with help-seeking. All of these reasons contribute to low numbers being reported to the city, state, and/or federal government.

The underreporting problem is exacerbated in studies of children, where we struggle with the issues associated with combining data from multiple informants, some of whom (the parents) may wish to avoid blame (real or perceived) for the problems of their children. Health care professionals are hesitant to assign diagnosis that may be stigmatizing.12 The underreporting of childhood emotional disturbances in rural areas and from the private sector (private schools and private physicians) has also been well documented.13–16

Another factor in the underestimation of emotional/behavioral disorders in young children is the lack of diagnosis due to lack of medical care, resulting from the lack of follow-up with a treatment plan for the family, and barriers such as medical care availability, poverty that affects transportation, or variations in types of medical care available. Parents/guardians are also often told their children will “grow out of it.” This presents problems because when they do not pursue treatment, the problem is not reported.

The field of infant mental health is relatively new and there are few people trained in relationship-based mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention practices. There are even fewer trained to understand how culture can be used as a resource in working with families. Furthermore, there is very little public understanding of the critical importance of early parent/child relationships and how they influence child development. Another challenge is the lack of standard measures of “need for treatment” (symptoms that require intervention), particularly those that are culturally appropriate. Such measures are at the heart of a public health approach to mental health.

Other studies report pediatricians receive relatively little training in child psychopathology and child development, leaving them ill-prepared and uncomfortable when addressing mental health problems. A recent study indicates that a substantial number of psychosocial problems raised during pediatric appointments are not addressed.16 In high-volume practices, this problem may be exacerbated by the relatively little time devoted to individual patients. It would be impossible for some pediatricians to complete an adequate mental health screening during a routine visit, as it would probably take 45–60 minutes to gather information about social/emotional development and other relevant issues.

Another factor that affects prevalence to some unknown degree is the underestimation of children counted by the U.S. Census. After each recent Census, the Census Bureau has undertaken a thorough assessment to determine the quality of the data collected (including post-enumeration surveys and demographic analysis). Surprisingly, the assessments have shown that children are missed more often than any other group. The Census Bureau estimates that more than 2 million children were missed in the 1990 Census, accounting for more than half the total net undercounted population.17 The estimated undercount rate for children below age 10 doubled, increasing from 2.0% in 1980 to 4.1% in 1990. (The 2000 undercount figures have not been published.)

It is noteworthy that the undercount rates for children are often high in the states where the child poverty rate is high, underscoring the link between living in poverty and being missed in the Census. For example, large cities have high poverty rates and high undercount rates among children.17 Most experts believe that this reflects the high undercount rate for people living in the moderately distressed inner-city neighborhoods. Undercount rates are even higher for minority children in many big cities. Many impoverished rural areas also experience high undercount rates. The high undercount rate for children means significant numbers of kids most in need of assistance are not even included in the data used to distribute public funds for supports and services.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Estimates of the number of children suffering from serious emotional/behavioral problems vary significantly depending on the study cited. A literature review revealed estimates ranging from 5% to 26%:

7% (15% mild) by Richman et al. (1975)18

11% by Earls (1980)19

11.8% by Gould et al. (1980)20

5% by Vikan (1985)21 (he considered socio-demographic variables an explanation for the low prevalence)

26% by Verhulst et al. (1985)22

14.1% by Cornely and Bromet (1986)23

16.5% by Offord et al. (1987)24

16% to 20% by Anderson et al. (1987),27 Costello et al. (1988a),28 Bird et al. (1989),29 Costello (1989),30 Velez et al.(1989),31 Brandenburg et al. (1990),13 Esser et al. (1990),32 McGee et al. (1990),33 and

3% to 21.4% by Lavigne et al. (1996)34

The variations in estimated prevalences might be explained in part by the varying reasons the studies were conducted—for example, developmental perspectives, patterns of symptoms, and studies of prevalence—and for what purposes their estimates would be used. The methodology for selecting the study populations also varied among the studies. The studies applied numerous diagnoses of disorder obtained from many types of reports and measures. They incorporated variations of reports based on structured interviews from different informants and data combining two or more sources. And their uses of “functional impairment” also varied. Studies reflecting higher prevalence rates represent a more inclusive cut-off point, while the lower prevalence rates tended to result from more conservative, less inclusive cut-off points. While it is impossible to compare scores of variant measures from different instruments used, it seems reasonable to conclude that a score of one (1) internal impairment may not be a good approximation of the Center for Mental Health Services/Office of Mental Health concept of “substantial” impairment. Such an inclusive cut-off may inflate estimates.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The first step toward ensuring that children receive the mental health services they need—and that are equal to all—is to perform more research that is generalizable to them and sensitive to diverse cultural groups. This goes hand in hand with establishing the use of valid and reliable screening measures for emotional/behavioral disorders appropriate to preschool-age children. Second, we must establish minimum levels of functional impairment with respect to duration and domains, and report prevalences in ranges. These steps would lead to a more appropriate, updated standard definition for emotional/behavioral disorders in very young children. A “Standard Developmental Risk Profile” would help provide early diagnosis for children at-risk. We must remove barriers to treatment, and last but not least, create a new, universal approach for supports and services for children and their families—a new “Comprehensive Early Childhood Mental Health Plan.”

Expand research and establish the use of valid and reliable screening measures

Expanded funding from non-profit, state, and federal agencies would enable more research that is data-sensitive to all cultural groups and generalizable to states and the U.S. This would be a huge step toward ensuring proper supports and services for preschool children with emotional/behavioral disorders and their families based on scientific relevance. System-wide problems, including the lack of appropriate training for pediatricians and development of effective mental health services for young children, must all be addressed. Until this subject is well studied, some of the concerns expressed about screening programs must be taken into account.35 These include the negative effects of labeling a child. Establishing standard, valid, and reliable screening measures for emotional/behavioral disturbances applicable to preschool children is key.

The use of a standardized, fully structured, self-administered epidemiological questionnaire for families and standardized screening measures for families and teachers/caregivers should be implemented throughout the U.S. These questionnaires can be an ongoing method to collect data for a much-needed database. The expense could be minimized by using a low-cost data collection method such as paper and pencil self administration (perhaps in the form of mail questionnaires), or a questionnaire administered in public health clinics, preschools, daycares, and private pediatricians' offices.

These standardized screening measures could be given to the parents/guardians, teachers/caregivers, and health care workers as a means to identify and treat the children at-risk and/or with emotional/behavioral problems earlier. These screening measures should be specifically for the preschool population.

Because most parents of preschoolers with emotional/behavior problems do seek assistance, screening whole communities, linking programs to preschools, or advertising statewide may increase participation in prevention or intervention programs for the future.

Substantial evidence indicates the benefits of early provision of interventions to prevent behavior problems and poor school performance.11,36 Accurate assessments of behavioral/emotional problems in preschool children is an important goal. The observation that untreated psychiatric problems in preschoolers often tend to persist at least into the grade school years emphasizes the great importance of accurate assessment and early identification. The evaluation of emotional/behavioral problems in preschoolers has traditionally relied on parent, teacher, or observer reports.37,38 It is important that future screening measures use multiple sources.

Multiple settings should also be considered because of the impact on the development of problem behaviors. The initial assessments will help identify important risk factors and protective factors that will lead us to the proper program of supports and services.

Define levels of impairment in ranges

There is little consensus on how minimum functional impairment should be defined or measured. Children must be seen in the context of their social environments—that is their family, their peer group, and their larger physical and cultural surroundings. According to the 1999 Surgeon General's report on mental health, “The developmental perspective helps us to understand how estimated prevalence rates for mental disorders in children vary as a function of the degree of impairment that a child experiences in association with specific symptom patterns. The science of mental health in children is a complex mix of development and the study of discrete conditions or disorders.”1 Both of these perspectives are useful. “Each alone has its limitations, but together they constitute a more fully informed approach that spans mental health and illness and allows one to design developmentally informed strategies for prevention and treatment.”1

In the absence of any “standard” that could be used as a basis for establishing a cut-off point for minimum functional limitation, and in the absence of any social validation process that has established a consensus on the threshold, data should be presented for many levels of impairment. This has the benefit of providing additional information to planners and policy makers, and to stimulate further discussion and research to establish an appropriate threshold. It has the disadvantage of possibly overestimating the occurrence of a serious health problem. A “standard” for an established cut-off point for minimum functional limitation must be approved; then and only then will we be all on the same page.

Report prevalence in ranges

Prevalence should be expressed in ranges, allowing treatment for children before they are “labeled” as emotionally disturbed. This would also allow for ranges of minimum functional limitation, rather then just one cut-off point. Expressing prevalences in ranges associated with minimum functional limitations would also address the need for variations for different age groups, racial and ethnic groups, genders, and socioeconomic groups. Based on our analysis of the findings from the studies reviewed, the sampling, measurement, overall methodological considerations, and levels of minimum functional impairment, we estimate the prevalence of emotional/behavioral disturbance in children 0–5 years of age is in the range of 9.5% to 14.2%.

Update the standard definition

The broad variation in criteria and methodology of the measures revealed in our literature search also makes it clear that those prevalence rates are not generalizable to individual states (such as my home state of Louisiana) and/or the United States. A clear updated standard might be to define an emotional/behavioral problem as: “Any behavior or range of behaviors listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) as a symptom of emotional/behavioral disorder or a problem description that is consistent with these symptoms, such as aggression at home and/or school, etc. for a shorter duration, and not in all domains (environments) and a specific range of minimum functional limitations.”

Bennett et al. stated, “However, through review of the scientific literature, there still needs to be further investigation to clarify the predictive validity of externalizing behavior symptoms in nonclinical populations for their usefulness as a risk assessment method. From a developmental perspective, substantial stability of externalizing behavior symptoms exists over time. However, from the perspective of prevention, significant levels of misclassification will occur when externalizing behavior symptoms are used to designate high risk status under the low prevalence conditions of a normal population.”39 I could not have stated this any clearer, which is why I strongly concur with his recommendation.

Despite the shortcomings in the conceptualization and measurement of minimum functional impairment, there is a relationship between emotional disturbance and use of mental health services. An updated standard definition would be useful to establish severity levels in determining the service implications of diagnoses. An updated standard definition would also allow an earlier and proper diagnosis of more of these children earlier in their lives, so they could also be treated earlier.

Given the vast differences in reporting of children with emotional/behavioral disorders and the lack of early diagnosis, a standard methodology for establishing prevalence with a “standard definition” should be used when planning programs for these children.

Create a standard “Developmental At-Risk Profile”

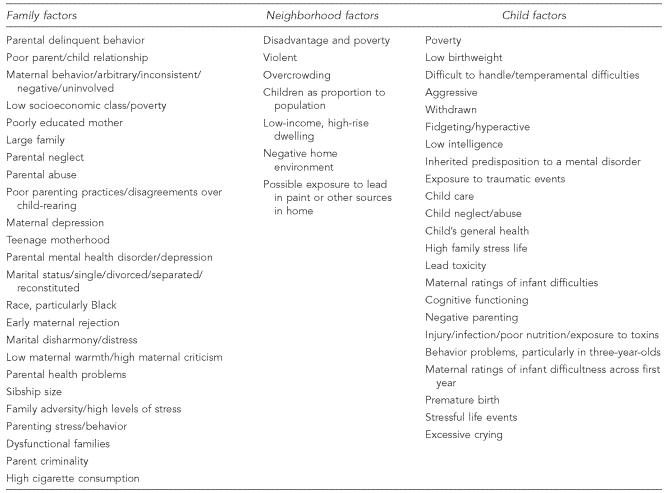

An established standard “Developmental At-Risk Profile” is in order to identify these children. The Figure shows a suggested developmental at-risk profile that could be implemented throughout the United States.

This profile represents the interaction of all the demographic factors. But one could ask, are these independent risk factors for emotional/behavioral problems? Only poverty has been identified as a powerful risk factor on its own, so much so that an algorithm for developing some state prevalence rate estimates includes an adjustment according to the state median income levels.26 However, given the evidence that few risk factors are disorder-specific, a broad-based approach to risk reduction is more appropriate than an approach based on specific risk factors.

A major challenge in psychiatric epidemiology is that, unlike chronic physical illnesses such as cancer and heart disease—which can be clearly linked to narrow risk factors such as diet and smoking—the onset of mental illness is related much more strongly to broad measures of environmental adversity. These broad, nonspecific risk factors are interrelated and usually combined. Again, given the evidence that few risk factors are disorder-specific, a broad-based approach should be implemented for future strategies. The focus of future studies should be areas of high child poverty rates, children exposed to stressful life experiences, aid to single parents with dependent children, and social support and coping mechanisms.

Remove barriers to treatment

Studies of the determinants of help-seeking show that financial barriers are significant obstacles to treatment, and that treatment rates increase when these barriers are removed.40 We must find financial sources to assist our citizens in receiving much-needed professional help. This is especially important in states like Louisiana, where the state funding situation is extremely grave.

We must also address the common perception that mental health problems will go away by themselves. Many people would rather deal with the problem themselves than pursue treatment or support. Many people believe that treatment will not be effective. These findings imply the perceived stigma related to mental illness. This alone is reason enough to begin a culturally diverse educational awareness campaign to educate our citizens about mental health diagnoses. It also highlights the need for community needs assessments—through focus groups in Louisiana and throughout the United States—to identify specific populations' perceptions of mental health as related to early childhood mental disorders. Public awareness/education campaigns will be critical in these efforts. Targeted secondary interventions for these populations should be used for two major reasons: first, the realization that many mental disorders begin at an early age; and second, the need to focus delivery of the interventions in high-risk segments of the population. Providing coping strategies for high-risk populations would be extremely beneficial. Other ways to reach these populations include using standardized conceptual models to study the help-seeking process that highlight the importance of health beliefs, including the perceived need for treatment, barriers to seeking treatment, and the perceived efficacy of treatment. These models will be useful in comprehending and altering the process in the future.

We must also develop a strategy for the delivery of mental health supports and services to children 0–5 years of age and their families. These services should assist in improving access to health care for families and offer parent training programs and resources. This multidimensional model should also address the need for education for physicians and health care workers on the importance of early identification of emotional/behavioral disorders. These model interventions should be community based, and located in high-poverty areas with high numbers of at-risk children and families, as identified by appropriate screening measures.

Another type of barrier that must be addressed is the need for regular and reliable estimates of the incidence/prevalence of child abuse and neglect based on sample surveys rather than administrative records. These children are at extreme risk for emotional/behavioral disorders, and must be identified early and correctly. Child abuse/neglect is another risk that alone can produce emotional/behavioral disorders in children. We cannot depend on administrative records to count these children, because these records report only cases that are substantiated; it is likely that official records of child abuse and neglect underestimate the magnitude of this problem. Estimates from sample surveys potentially provide more accurate information of child abuse and neglect; however, we must consider how to effectively elicit this sensitive information. We must also consider whether there is an ethical responsibility to report abuse or neglect discovered in the course of research.

Create and implement a new “Early Childhood Mental Health Plan”

If implemented, our recommendations will lead to continued research and will form the basis for creation and implementation of future interventions and the adoption of a new comprehensive Early Childhood Mental Health Plan. This new approach to the way Louisiana and the U.S. treats its very young is important to our future and will allow our children to contribute to and live a “normal” existence in our state and nation.

CONCLUSION

This commentary is not the final word. More work and research must be done so that we can determine the most accurate prevalence of emotional/behavioral disorders in children 0–5 years old in Louisiana and the United States. The challenge that lies ahead is formidable but worthwhile.

After deriving the estimated prevalence of children suffering with these disorders, our next step in developing effective interventions is to discover and understand the attitudes, practices, and beliefs of these children and their families so that they can be reached “on their own playing field.” These factors should be taken into account when planning and delivering services for children and families with mental health problems. Services must be culturally competent. All cultures practice traditions that support their children and prepare them for living in their society. Service providers must be trained in specific behaviors, attitudes, and policies that recognize, respect, and value the uniqueness of individuals and groups whose cultures are different from those associated with mainstream America. Parenting styles and the importance of the values, beliefs, traditions, and customs of these families must be recognized and respected by culturally competent service providers.

The challenges that lie ahead are formidable, but very worthwhile for public health workers like me, whose job is to work in the state's system to represent our very young children at-risk and/or with mental health problems. We need to step forward and demand a clear, inclusive, and “standard” definition for emotional/behavioral disorders for our very young; we need to be their voices. This will have a domino effect, facilitating the creation of more and better supports and services, more effective educational programs, and ultimately, healthier children, adolescents, and adults. By addressing all of these problems, we will effect drastic changes in our numerous educational problems, along with decreases in crime. The list can go on and on, and the benefits can be innumerable if we face these challenges together as a team, fighting as representatives and workers for our very young children. They need us more than ever at this most vulnerable time of their lives, so that their lives will be more functional, healthy, and productive. We need to help these young children achieve their maximum potential—the health and well-being that they deserve and require. When there is hope, and appropriate supports and services for these children, then and only then will our future be brighter.

Figure.

Proposed Developmental At-Risk Profile

NOTE: The majority of these risk factors are interrelated and not independent of each other. Poverty alone is the only risk factor not interrelated, but is associated with many mediating variables.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US); Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckwith L, Cohen SE. Maternal responsiveness with preterm infants and later competency. New Dir Child Dev. 1989;43:75–87. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219894308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denham SA, Mitchell-Copeland J, Stranberg K, Auerback S, Blair K. Parental contributions to preschooler's emotional competence: direct and indirect effects. Motivation and Emotion. 1997;27:65–86. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Supportive parenting, ecological context, and children's adjustment: a seven-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 1997;68:908–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson RA. Handbook of attachment: theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. Early attachment and later development. In: Cassidy J and Shaver PR, editors; pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ainsworth MDS. The development of mother-infant attachment. In: Caldwell BM, Ricciuti HN, editors. Review of child development research. Vol. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1973. pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern D. The first relationship: infant and mother. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winnicott DW. The maturational process and the facilitating environment. New York: International Universities Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell SB. Longitudinal studies of active and aggressive preschoolers: individual differences in early behavior and outcome. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Internalizing and externalising expressions of dysfunction: Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology. Vol. 2. Hillsdale (NJ): Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loeber R. Antisocial behavior: more enduring than changeable? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:393–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramey CT, Ramey SL. Early intervention and early experience. Am Psychol. 1998;53:109–120. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health and Human Services (US); Rockville (MD): DHHS. Psychiatric epidemiology: recent advances and future directions. 1999. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services.Mental health, United States, 2000. Section 2; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandenburg NA, Friedman RM, Silver SE. The epidemiology of childhood psychiatric disorders: prevalence findings from recent studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:76–83. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services (US); Rockville (MD): DHHS. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Center for Mental Health Services. Mental health, United States, 2000. Section 2; Chapter 5. Psychiatric epidemiology: recent advances and future directions. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costello EJ, Burns BJ, Angold A, Leaf PJ. How can epidemiology improve mental health services for children and adolescents? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:1106–1117. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp L, Pantell RH, Murphy LO, Lewis CC. Psychosocial problems during child health supervision visits: eliciting, then what? Pediatrics. 1992;89:619–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bureau of the Census (US) Washington: Government Printing Office; 1992. Census of population: 1990, general population characteristics, United States. 1990-CP-1-1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richman N, Stevenson JE, Graham PJ. Prevalence of behavior problems in 3-year-old children: an epidemiological study in a London borough. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1975;16:277–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1975.tb00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earls F. Prevalence of behavior problems in 3-year-old children: a cross national replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:1153–1157. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780230071010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould MS, Wunsch-Hitzig R, Dohrenwend BP. Formulation of hypotheses about the prevalence, treatment, and prognostic significance of psychiatric disorders in children in the United States. In: Dohrenwend BP, Dohrenwend BS, Gould MS, editors. Mental illness in the United States. New York: epidemiological estimates; 1980. pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vikan A. Psychiatric epidemiology in a sample of 1,510 ten-year old children. I. Prevalence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1985;26:55–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1985.tb01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verhulst FC, Akkerhuis GW, Althaus M. Mental health in Dutch children: I. A cross cultural comparison. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1985;323:1–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1985.tb10512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornely P, Bromet E. Prevalence of behavior problems in three-year-old children living near Three Mile Island: a comparative analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1986;27(4):489–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Offord D, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, Rae-Grant NI, Links PS, Cadman DT, et al. Ontario Child Health Study II: six month prevalence of disorder and rates service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:832–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210084013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman RM, Kutash K, Duchnowski AJ. The population of concern: defining the issues. In: Stroul BA, editor. Children's mental health: creating systems of care in a changing society. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes. 1996. pp. 69–95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman RM, Katz-Leavy JW, Manderscheid RW, Sondheimer DL. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services. Prevalence of serious emotional disturbance on children and adolescents. In: Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA, editors. Mental Health, United States, 1996. 1996. pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson JC, Williams S, McGee R, Silva PA. DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children. Prevalence in a large sample from the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:69–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800130081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costello EJ, Costello AJ, Edelbrock C, Burns BJ, Dulcan MK. Psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care. Prevalence and risk factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:1107–1116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360055008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bird HR, Gould MS, Yager T, Staghezza B, Canino G. Risk factors for maladjustment in Puerto Rican children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:847–850. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costello EJ. Developments in child psychiatric epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:836–41. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velez CN, Johnson J, Cohen P. A longitudinal analysis of selected risk factors for childhood psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:861–864. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esser G, Schmidt MH, Woerner W. Epidemiology and course of psychiatric disorders in school age children: results of a longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1990;31:243–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Partridge F, Silva PA, Kelly J. DSM-III disorders in a large sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:611–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavigne JV, Gibbons RD, Christoffel KK, Arend R, Rosenbaum D, Binns H. Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric disorders among preschool children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:204–214. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199602000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feldman W. How serious are the adverse effects of screening? J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:S50–S53. doi: 10.1007/BF02600842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zigler E, Taussig C, Black K. Early childhood intervention. A promising preventative for juvenile delinquency. Am Psychol. 1992;47:997–1006. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.8.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behar L, Stringfield S. A behavior rating scale for the preschool child. Dev Psychol. 1974;10:601–610. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Earls F, Jacobs G, Goldfein D, Silbert A, Beardslee W, Rivinus T. Concurrent validation of behavior problem scale to use with 3-year-olds. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1982;21:47–57. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett K, Lipman E, Brown S, Racine Y, Boyle M, Offord D. Predicting conduct problems: can high risk children be identified in kindergarten and grade 1? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:470–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]