SYNOPSIS

Objectives

Workers’ compensation insurance in some states may not provide coverage for medical evaluation costs of workplace exposures related to potential bioterrorism acts if there is no diagnosed illness or disease. Personal insurance also may not provide coverage for these exposures occurring at the workplace. Governmental entities, insurers, and employers need to consider how to address such situations and the associated costs. The objective of this study was to examine characteristics of workers and total costs associated with workers’ compensation claims alleging potential exposure to the bioterrorism organism B. anthracis.

Methods

We examined 192 claims referred for review to the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation (OBWC) from October 10, 2001, through December 20, 2004.

Results

Although some cases came from out-of-state areas where B. anthracis exposure was known to exist, no Ohio claim was associated with true B. anthracis exposure or B. anthracis-related illness. Of the 155 eligible claims, 126 included medical costs averaging $219 and ranging from $24 to $3,126. There was no difference in mean cost for government and non-government employees (p=0.202 Wilcoxon).

Conclusions

The number of claims and associated medical costs for evaluation and treatment of potential workplace exposure to B. anthracis were relatively small. These results can be attributed to several factors, including no documented B. anthracis exposures and disease in Ohio and prompt transmission of recommended diagnostic and prophylactic treatment protocols to physicians. How employers, insurers, and jurisdictions address payment for evaluation and treatment of potential or documented exposures resulting from a potential terrorism-related event should be addressed proactively.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, affected United States citizens in many ways: loss of life, injuries, destruction of well recognized landmarks, loss of jobs for thousands of workers, short- and long-term economic losses, and psychological effects of a bioterrorism incident within the United States. Businesses, including insurance companies, need to anticipate the potential for a similar terrorism incident in the future and plan accordingly. For example, key issues for insurance companies include whether to include coverage to clients for acts of terrorism, and if coverage is offered, what is covered and what is the potential cost of that coverage to the client.1,2

Workers’ compensation insurance in many jurisdictions may have its own unique issues as a result of potential terrorism events. Employers purchase workers’ compensation insurance to provide coverage for medical costs, lost wages, and permanent disability for their employees should they become injured or develop an illness directly related to the work environment. In return, the employer is protected from legal action by its employees for work-related injuries and illnesses unless there are negligent actions on the part of the employer. Usually medical and indemnity benefits are defined by individual state laws, and in many states, benefits are paid only if there is a work-related injury or illness that is accidental in nature. Some states may provide coverage for incidental exposure, such as exposure to body fluids infected or potentially infected with biological pathogens. Other states may require employers to provide coverage for such incidents using the requirements of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). However, the potential exposures resulting in the claims in this study are different from other biological pathogen exposures in several ways: (1) there is no OSHA standard pertaining to the exposure; (2) the potential exposures could not be reasonably anticipated since most were from concern about dust or powder on objects or from mail; (3) the injured worker was frequently instructed to seek medical treatment; and (4) the exposure incident was not accidental in nature. Key issues that have arisen in the wake of September 11, 2001, include whether workers’ compensation benefits should be administered when the event or exposure is not accidental in nature or when medical evaluation and treatment is delivered as a prophylactic measure with no definable injury or illness.

In October 2001, Americans were confronted with a different type of terrorism as the United States Postal Service was used to deliver mail contaminated with B. anthracis spores to several locations including American Media Inc. in Florida, NBC News in New York, and Senator Tom Daschle’s office in Washington. At least three postal facilities and workplaces were contaminated and several people were exposed, resulting in at least two deaths.3 Due to the unknown source of the biohazard, there was concern across the country about personal exposure to “white powder.” Police and fire responders were called to workplaces when an envelope or package was opened and reportedly contained a suspicious substance or odor. Many times the employee was advised to seek medical treatment, particularly regarding potential B. anthracis exposure, since early use of antibiotics may be effective in preventing B. anthracis-related illnesses. When employees sought medical care for this exposure, immediate questions arose about what entity would cover the costs of the medical evaluation and treatment—the employer, private insurance, the employee, or workers’ compensation insurance.

OHIO BUREAU OF WORKERS’ COMPENSATION

The Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation (OBWC) provides workers’ compensation insurance to Ohio’s employers and employees except those larger employers that qualify as self-insured. More than two-thirds of the Ohio workforce is covered by OBWC. The OBWC’s mission is “to provide a quality, customer-focused workers’ compensation insurance system for Ohio’s employers and employees.” In fiscal year 2002, OBWC insured 277,306 employers, received 236,344 new claims, and paid more than $1.9 billion in benefits. The OBWC Oversight Commission provides advice and consent to the OBWC Administrator regarding a variety of issues. This commission is comprised of two representatives of Ohio’s workforce, two representatives of employers, and one member representing the public. As a result, OBWC is concerned with the perspectives of employers, employees, and the general public.4

Ohio workers’ compensation statutes define occupational injury as “any injury, whether caused by external accidental means or accidental in character and result, received in the course of, and arising out of the injured employee’s employment.” Occupational disease is “a disease contracted in the course of employment, which by its causes and the characteristics of its manifestation or the condition of the employment results in a hazard which distinguishes the employment in character from employment generally, and the employment creates a risk of contracting the disease in greater degree and in a different manner from the public in general.” According to Ohio statutes, a worker must have “contracted” a specific disease from a workplace exposure for the individual to be eligible for workers’ compensation benefits. Claims that represent a mere exposure without development of a disease are non-compensable in Ohio.5 The OBWC does not pay for services to determine whether a disease is present without the claim becoming officially recognized for the disease.

Given the amount of media coverage of the B. anthracis exposures spread via parcels delivered by the postal system and the heightened awareness of terrorism as a result of September 11, it was expected that Ohio employees would be concerned when handling or opening mail and finding any unusual substance. Moreover, when these employees were instructed to be medically evaluated, the question arose as to who would be responsible for the medical costs in the absence of disease or injury. In most cases, private insurance would not provide coverage and many employers had no specific company policy to cover the costs for such services, which could be significant depending on the number of employees potentially exposed. The purpose of this article is to describe the process the OBWC used to address these issues and the results experienced to date. Specific objectives were to: (1) describe the process implemented and the factors affecting its outcome; (2) describe characteristics of workers involved, including demographics and jobs; (3) identify potential administrative and payment problems; (4) assess overall costs; and (5) compare claims submitted by employees of government and non-government entities.

METHODS

In response to the October 2001 B. anthracis-contaminated mail situation, the OBWC implemented a policy for handling claims related to alleged bioterrorism. Under this process, all claims alleging potential exposure to B. anthracis or other bioterrorism agents undergo two reviews: a central processing unit review followed by an OBWC Medical Advisor review. The central processing unit review includes an investigation of the circumstances including the potential exposure, whether emergency response personnel were utilized, and whether the individual was instructed by the response personnel or supervisor to seek medical care. This information and available medical records are referred to the OBWC Medical Advisor for review. The Medical Advisor review includes documentation that no injury or disease existed at the time of the medical evaluation.

For purposes of this analysis, data included all claim management and bill payment data available at OBWC from 192 claims referred between October 1, 2001, and December 20, 2004. This end date was three years after implementation of the policy and allowed time for processing, adjudication, and payment of most claims.

Case definitions

Based on the central processing unit and OBWC Medical Advisor reviews, the 192 claims included in this study were classified into three case definitions: “deny/pay,” “deny/no pay,” or “allowed.” (Once an OBWC decision is made, the employee and employer are notified of the decision and payment is made to the medical providers per the OBWC fee schedule for “allowed” and “deny/pay” claims. Any objections to the OBWC decision can be appealed to the Ohio Industrial Commission for adjudication.)

“Deny/pay” claims

For claims in which the medical evaluation demonstrated no evidence of illness or injury, the claim was denied in accordance with Ohio law. However, provided that there appeared to be an exposure at the workplace and the individual was instructed by the emergency responders at the scene or the employer/supervisor to seek medical care, OBWC did reimburse for the emergency medical services necessary to investigate the potential exposure, the associated medical evaluation, and prophylactic therapy consistent with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) protocols. These claims were designated as “deny/pay” (deny the claim/pay for medical evaluation services and prophylactic therapy only).

“Deny/no pay” claims

Claims in which the record indicates the employee was not exposed at the worksite or was not instructed to seek medical evaluation by the emergency response personnel or supervisor were denied and medical services were not reimbursed. These claims were designated as “deny/no pay” (deny the claim/no payment for medical evaluation services).

“Allowed” claims

If the exposure incident resulted in a medical diagnosis, the claim was handled as an occupational disease claim and benefits were paid accordingly. For example, an exposed individual may develop irritation of the eyes, allowing a claim for chemical conjunctivitis; therefore, all costs related to the diagnosis and treatment would be covered.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using claims categorized as “deny/pay.” These claims were further categorized as submitted by government or non-government employees. The first responders in most cases are government employees whose jobs require them to be potentially exposed, and there is public sentiment to guarantee coverage for these individuals. Characteristics and costs between government and non-government claims were compared using chi-square test for dichotomous variables and t-test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables using SAS,6 and significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 192 claims referred to the OBWC between October 10, 2001, and August 20, 2004,five (2.6%) were allowed, 32 (16.7%) were denied with no payment of any services, and 155 (80.7%) were denied with payment for the initial medical evaluation and treatment provided. There were no reported positive B. anthracis tests in Ohio during this time and there were no OBWC allowances for a B. anthracis-related diagnosis. The five allowed claims had medical records supporting a diagnosis related to the exposure but not related to B. anthracis or other bioterrorism agents. Three of these individuals were involved with the same exposure incident and diagnosed as toxic effect to gas or vapor with symptoms of lightheadedness resolving over a short period of time. Another individual had facial burning and eye irritation and was diagnosed as unspecified allergy. The last individual had symptoms of chemical conjunctivitis. Total medical costs for these five claims were $1,247.95. The 32 claims that were denied with no payment for medical evaluation were denied because of lack of documentation of instruction to seek medical care by the emergency responders or supervisor.

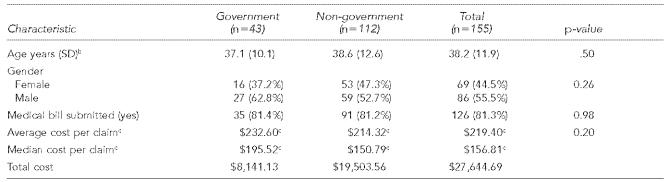

Of the 155 “deny/pay” claims, 86 (55.5%) were male and 69 (44.5%) were female (Table 1). The majority of these claims (89.0%) were submitted in 2001: October (84 claims), November (45 claims), and December (9 claims). There were 13 claims submitted in 2002, none in 2003, and four in 2004. The four claims in 2004 involved two police officers from one department and two government workers who opened an envelope that contained an unusual substance. Government and non-government employees submitting a claim did not differ significantly by age or gender.

Table 1.

Characteristics of workers by employer status for 155 “deny/pay” claimsa

Deny/pay claims demonstrated no evidence of illness or injury. However, OBWC did reimburse for the emergency medical services necessary to investigate the potential exposure, associated medical evaluation, and prophylactic therapy consistent with CDC protocols.

Two claims with missing data on age (one government and one non-government)

Cost per claim of the 126 claims with medical bills submitted: government (n=35) and non-government (n=91)

SD = standard deviation

Of the 155 claims, medical payments were made in 126 claims, resulting in $27,645 being reimbursed to providers. There were no indemnity payments as no individual sustained any lost time and there was no permanent impairment. Of the 155 claims, the average medical cost per claim was $178 with a median cost of $134 (data not shown). Overall, 81.3% of these claims (126) were associated with a medical bill, with similar percents for government and non-government employees. There were no medical payments associated with 29 claims. If these 29 claims are eliminated from analysis, the average medical cost per claim of the remaining 126 was $219 with a median cost of $157 (Table 1). Although cost per claim was higher in government compared to non-government employees, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.202). Actual medical cost per claim ranged from $27 to $684 and $24 to $3,126 for government and non-government claimants, respectively. This includes one individual who had been working in an environment where B. anthracis spores were confirmed and who presented with a febrile illness and was hospitalized. A B. anthracis-related illness was never diagnosed and he most likely had a non-work-related exposure to another pathogen. His claim was handled as a “deny/pay” because OBWC determined that if he had not been in a facility with documented B. anthracis exposure, he most likely would not have been hospitalized.

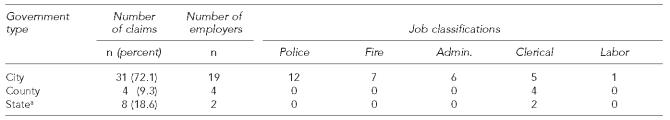

Of the 155 “deny/pay” claimants, 43 (27.7%) were working for a government entity and 112 (72.3%) were working in non-government positions. For the 43 government workers, Table 2 shows the number of employers and claims, and describes type of work. Although 25 employers were involved, police and firefighters, who were the first responders to many of the incidents, accounted for 44.2% (19) of the 43 claims. Of the eight state employees, six were from one exposure that occurred when opening mail in a prison.

Table 2.

Government employees: number of claims by type of government employer and job classification (N=43)

Six of the eight were prison employees who were exposed to a substance while opening mail.

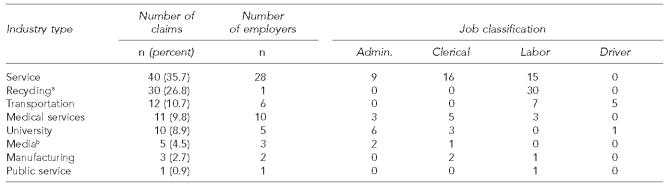

Claim information for the 112 employees working in non-government type jobs is provided in Table 3. One employer had 30 claims as the result of a suspicious substance being found in the facility, which resulted in the entire facility being closed on advice of the county health department.

Table 3.

Non-government employees: number of claims by type of industry and job classification (N=112)

Represents one facility closed by the county health department; employees were instructed to seek medical evaluation.

In two cases, the type of work was unknown.

Of the 155 “deny/pay” claims, the alleged exposure of three individuals occurred outside the state of Ohio. One individual had recently visited a facility in another state that had documented contamination and became ill after returning to Ohio. The individual was evaluated and ultimately diagnosed with an illness not related to B. anthracis. Another individual had visited a B. anthracis-contaminated facility in another state and was advised by the employer to be medically evaluated and provided medication. A third individual had been working in a clean-up effort of a facility known to be contaminated with B. anthracis.

DISCUSSION

This case series illustrates potential problems encountered by payment systems, such as workers’ compensation, when possible bioterrorism events occur. These types of incidences were not anticipated when laws and regulations were drafted to define benefits delivered by current workers’ compensation systems.

The OBWC took a proactive stance in response to these potential workplace exposures by providing coverage if specified criteria were fulfilled. These criteria and the procedures used to process the claims attempted to ensure that coverage was provided to employees who had an exposure incident and were instructed by their supervisor or the emergency responder to seek medical evaluation. Establishing objective criteria and a process to review such criteria are essential in evaluating this type of claim. The OBWC could have denied all claims and payment in this series based on Ohio law. This position would most likely have been upheld in the adjudicatory process since none of the cases had a medically confirmed diagnosis. If this had occurred, the medical provider who performed the initial evaluation could bill the employer, the employee, or the insurance carrier for the employee. The employee would have ultimate responsibility for the incurred costs. This position was not considered optimal given the national circumstances during this timeframe. Several of the cases involved police officers and firefighters who were first responders, and denying them payment in the aftermath of September 11 was not deemed appropriate from an ethical and public health perspective.

The OBWC decision to deny the claims (but pay the cost of the medical evaluations) is considered important because denying the claims removes entitlement of benefits, since the claims are never allowed and as such there are no allowed conditions. At the time of implementation, there was some concern about potentially prolonged claims and potential subsequent costs associated with adjudication of the costs of the medical evaluations. By covering the cost of the medical evaluation and treatment when the employee was instructed to seek medical care because of a potential exposure, OBWC addressed these concerns proactively.

Since OBWC is the only workers’ compensation insurer in Ohio and its Oversight Commission is composed of representatives from employers and employees, there may be more incentive for OBWC to make coverage decisions that are in the best overall interest of employees and employers rather than of private insurers who offer similar services but must be concerned with shareholders and return on investment. It is important that the OBWC maintain good relationships with employees, employers, and the medical community to ensure delivery of future medical services. Denial of payment could adversely affect these important relationships.

Once OBWC created criteria and a process for evaluation of such claims for payment, the process was communicated to employers, medical providers, and the public through the OBWC website, provider update mailings, billing and reimbursement manuals, and notices or articles included in mailings sent from key professional and employer organizations to their members. Despite these efforts, it appears that the amount of reimbursement was considerably less than that which would be expected in these claims. This is illustrated by the fact that 29 of the 155 claimants (18.7%) were not issued medical payments by the OBWC. One explanation is that many medical providers billed the employer for services rendered, since it is well recognized that historically the OBWC pays only for specific diagnoses in allowed claims. Another explanation includes the employee paying the bill directly. Regardless of the reason for less-than-expected reimbursement, organizations such as OBWC must ensure all means of communication are utilized when policies specific to an unusual event are implemented.

In fiscal year 2002, OBWC insured 277,306 employers, received 236,344 new claims, and paid more than $1.9 billion in benefits (indemnity and medical). Of the 155 “deny/pay” claims, the majority (89.0%) were submitted in 2001: October (84 claims), November (45 claims), and December (9 claims). There were 13 claims submitted in 2002, none in 2003, and four in 2004. The total medical cost of these “deny/pay” claims was $22,644.69. The total medical cost of all OBWC claims during this period was roughly $800 million per year. Therefore, during this data collection period (3.25 years from October 2001 to December 2004), these claims represented 1% of all medical reimbursements. If the potential for risk exposure were greater, this proportion would be significantly greater.

The OBWC policy provided for payment of prophylactic medications prescribed at the time of initial evaluation. However, there were no pharmacy payments associated with any of the claims. Possible explanations include the prescriptions for prophylactic medication were not filled, the prescriptions were invoiced to the individual’s private insurance carrier, the employee covered the cost, or the employer reimbursed the employee for pharmacy costs. Not receiving the prescribed medication could have had significant impact if the workplace exposure resulted in B. anthracis-related disease. The costs of treatment of only one individual diagnosed with B. anthracis and the associated public health implications would have more than offset the costs of providing prophylactic medication to potential exposed individuals.

The total number of claims submitted may have been reduced by media coverage and information available to the public via the internet from the Ohio Department of Health (ODH) and the CDC. While the concern with potential exposure to B. anthracis was increased by the media initially, reports of recommended treatment, location of confirmed exposures nationally, and lack of continued confirmed exposures may have contributed to limiting the duration of the concern among the Ohio public. Most physicians had never evaluated or treated a patient with B. anthracis or a potential B. anthracis exposure. Physicians who encountered potentially exposed patients most likely reviewed guidelines from treatment authorities such as the CDC. Many early potential exposure and medical evaluation cases included more extensive evaluations and diagnostic studies (such as chest x-rays and blood cultures) as compared to later cases where medical records indicated individuals were counseled, provided a prescription for prophylactic medication, and asked to return if specific symptoms developed.

The OBWC and Ohio employees and employers are fortunate that no documented cases of B. anthracis exposure or illness occurred within the state. If a B. anthracis exposure was identified, the number of claims may have increased, resulting in increased costs and administrative burden. If a B. anthracis-related illness occurred that was related to a work exposure, the claim most likely would be recognized as compensable and OBWC would have been responsible for the associated costs and any death benefits due to the illness. One positive case could far exceed the total payments in all of the exposure claims included in this study.

While workers’ compensation benefits within a state are controlled by state statutes and costs for the benefits are paid by the insurer for the employer, it may be reasonable to ask whether there is a role for the federal government in either subsidizing or providing some form of coverage for such unusual exposures or those exposures in which the state or employer have no control. Had these or similar exposures resulted in a large number of claims resulting in long-term disability, high medical costs, or death, many states and insurers would have difficulty maintaining coverage at a reasonable cost to employers. The result could be devastating to the workers’ compensation insurer, the employers covered by the carrier, and the regional economy.

CONCLUSION

This report describes some of the problems encountered when applying the concerns of bioterrorism in the workplace to traditional workers’ compensation systems. Though a policy was developed in this instance and there were no contracted illnesses as a result of the exposure, jurisdictions such as states must determine how to address exposures and any injuries or illnesses resulting from non-accidental exposures, particularly when neither the employee nor employer is at fault. Widespread illness or major catastrophic events such as those of September 11, 2001, could financially destroy insurers if they are responsible for the large numbers of injuries, illnesses, or deaths. Even if the insurer survived the initial claims, the costs incurred could substantially increase subsequent premiums for employers or the insurers may opt not to provide coverage at any cost. If the employer is directly responsible for all costs, a few severe illnesses or deaths could be sufficient to bankrupt even a large employer, causing loss of jobs for many employees, loss of services for the employer’s client base, and loss of tax revenue for local and state government. If the employee or his/her survivors are responsible for evaluation and treatment of such an exposure and/or illness, the medical and lost-work wages could be devastating, particularly if a severe illness or death resulted. Governmental entities, insurers, and employers should proactively consider how to address such costs in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded by the Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kunreuther H. The role of insurance in managing extreme events: implications for terrorism coverage. Business Economics. 2002 Apr;37:6–16. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhooge LJ. A previously unimaginable risk potential: September 11 and the insurance industry. American Business Law Journal. 2003;40:687–779. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begley S. Tracking anthrax. Newsweek. 2001 Oct;29:36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohio Bureau of Workers’ Compensation and Industrial Commission of Ohio. Fiscal Year 2003 annual report. Columbus: OWBC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohio Industrial Commission and Bureau of Workers’ Compensation Laws. Cincinnati: Anderson Publishing Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.SAS Institute Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc; 2002. SAS Version 8.2. [Google Scholar]