Schools of medicine and nursing have recognized the need for their students to understand the diverse health problems of homeless populations, and in response, have taken steps to provide educational opportunities including formal instruction and practicum experiences.1–6 Such education is an effort to ameliorate students’ negative perceptions of individuals experiencing homelessness,7 align provider perceptions of service needs with the needs of homeless clients,8–10 and equip students with the skills and confidence necessary to provide services and outreach.1 However, structured formal education focused on the health needs of homeless populations has received less attention from schools of public health.

The health and human service agencies that serve the homeless are frequently over-burdened and understaffed. Consequently, they are often unable to fully meet the needs of their clients, often because these organizations lack funding, time, and clinical expertise in specialized areas.11 Despite these limitations, agencies serving homeless populations report that students enrolled in academic courses or as volunteers can fill a vital role in the provision of services. Many of these agencies are willing to provide educational experiences to students.12 Schools of public health have a unique opportunity to provide service learning opportunities that simultaneously meet the educational needs of students and the programmatic needs of agencies serving homeless populations.

In Spring 1993, the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH) and Health Care for the Homeless of Maryland (HCH) introduced a course entitled “Health and Homelessness.” Designed to bring academic and practice partners together, the course had several purposes: (1) educate students from a number of disciplines about the health and psychosocial problems that diverse homeless populations experience; (2) provide students with knowledge about the local, state, and federal policies that have conversely created and reduced the problem of homelessness; (3) provide students with experience learning from and working directly with individuals who are homeless; (4) meet the needs of local health and human services agencies that serve the homeless; and (5) engage in a sustainable community/academic partnership that has a long-lasting impact on Maryland’s homeless populations.

The course was initially funded over a five-year period by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Community-Based Public Health Initiative. This initiative was an effort to enhance the ability of underserved communities to identify and respond to health issues and influence the health system through academic/practice partnerships and to train the future health provider workforce. The initiative emphasized shifting from a services orientation to a community capacity-building orientation. In the context of the Health and Homelessness course, the practice partners, including HCH, examined the effectiveness of their own organizations while expanding their relationships with the community and academia. Using a multidisciplinary approach, HCH and other community partners actively engaged students into their practice settings while fulfilling their organization’s service needs. JHSPH included practice partners in teaching and research in an effort to actively address the health needs of homeless individuals.

COURSE STRUCTURE

Instructors

A diverse team of instructors was assembled to meet the goals of the W.K. Kellogg initiative and to address the multifaceted aspects of homelessness. Course instructors include men and women who are currently homeless, academic researchers, health and human service providers, advocates, and policymakers. Men and women who are currently homeless are invited from local transitional housing and shelters to provide their personal accounts of the causes and consequences of homelessness and to suggest strategies that will better serve the homeless and eliminate homelessness. Academic researchers with expertise in research and serving homeless populations serve as instructors, presenting empirical investigations that address the magnitude of homelessness and prevalence of health conditions among homeless populations, as well as strategies to address the problem. City government officials from the homeless services and housing departments are invited to address the local impact of homelessness and explain the organization of public- and private-sector homeless services. Clinicians from HCH, as well as leaders from local hospitals, shelters, and transitional organizations, are included to address the challenges of delivering health and human services to homeless populations, to explain the barriers homeless individuals must overcome to receive adequate care, and to provide in-depth knowledge of providing care to homeless populations. Advocates and public policy researchers from organizations including HCH, the National Coalition for the Homeless, and the National Center on Homelessness and Poverty present policy strategies aimed at preventing and reducing homelessness.

Process and goals

Classroom instruction constitutes approximately 30% of the students’ time. Throughout the course, students spend approximately 70% of their time engaged in their service learning projects. The goal of the project is to meet the education needs of students while also fulfilling the needs of local agencies. In developing the course, the primary instructor (LB) and HCH clinical director met with several transitional housing directors and community organizations to establish a collaborative relationship and engage organizations in participating in the course. These organizations included night emergency shelters, health care providers, soup kitchens, transitional housing facilities, drug and alcohol rehabilitation clinics, drop-in centers, and city departments of public health and housing. During these meetings, leaders from each organization were asked to describe their policy, program, and/or clinical needs. The organizations were then asked how they would improve services and what organizational goals they were unable to meet due to time, staff, logistics, or funding limitations. They were also asked how the needs of their clients could be met by a group of students with a diversity of talents and experiences. Based on these initial and follow-up meetings with the primary instructor, potential service learning projects were created. This process of the primary instructor engaging agencies is repeated each time the course is offered. Groups of students then meet with the agency leaders to finalize project ideas and ensure that both the agency service needs and student education needs will be met. During the course, the primary instructor frequently receives progress reports from students and meets with agency leaders to ensure that the projects are fulfilling the needs of the agency and are providing the students with new skills and knowledge. Following the project completion, a final report from each student is required for the agency and JHSPH. The report describes the project and potentially makes recommendations to the agency that may result in improved services or changes in policy. Students also prepare short presentations to share their experiences and receive feedback from the course instructors and other students. Community members and agencies are invited to attend these presentations.

Content

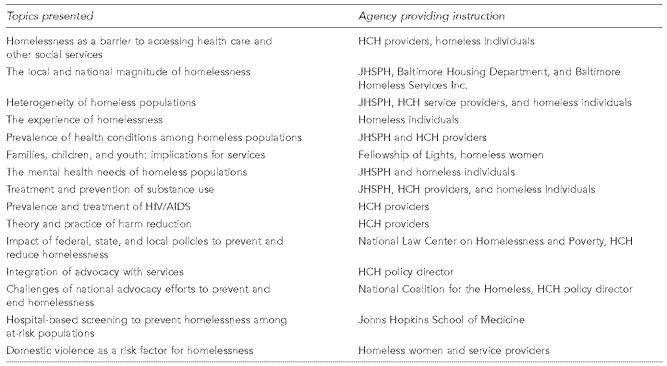

Course instruction has converged research, theory, and practice. Figure 1 presents a list of topics that have been presented by instructors during the history of the course and that are commonly included during each course offering.

Figure 1.

“Health and Homelessness” course instruction topics

HCH = Health Care for the Homeless

JHSPH = Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Service learning projects

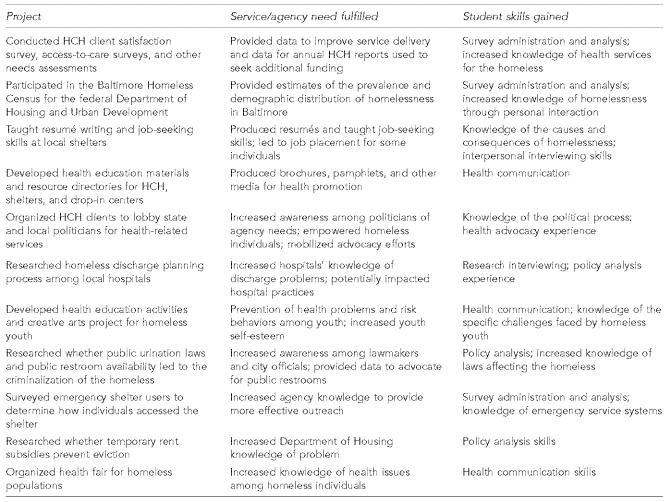

Figure 2 summarizes the types of service learning projects developed by matching the needs of community agencies with students’ interests and the course objectives. Course projects have involved survey development, implementation and analysis, job training, health fairs, development of educational materials, policy analysis, advocacy, and research reviews. Students pursuing studies in health services research have often elected to participate in projects where they gain survey administration and data analysis skills. Clinical students have had the opportunity to gain experience working in clinical settings that serve homeless individuals. Students of health policy have often chosen to evaluate laws and policies that impact homeless populations. Finally, health education students have taken an active role in developing and implementing health education materials for service providers.

Figure 2.

“Health and Homelessness” service learning projects

Students

The course is offered to undergraduate and graduate public health students, as well as medical, nursing, and public policy students in an effort to provide a more enriching and interdisciplinary experience. The collaboration between university divisions requires planning to reduce scheduling conflicts and ensure that the maximum number of students is able to participate. Due to scheduling changes within the semester and quarter system and the job-related demands of a multidisciplinary teaching team, the classroom portion of the course is offered during weekends.

Course progress

The course has been offered 16 times and has enrolled a total of 449 students since 1993. It is now financially supported entirely by JHSPH, yet community agencies still voluntarily provide instruction and involve students in their practice and research. Each year the number of interested students exceeds the capacity of local agencies and instructors. At least 20% of students who request permission to enroll in the course are turned away because the enrollment has exceeded capacity. The Saturday workshop format has enabled a greater number of students, instructors, and homeless individuals to participate in the course than would be possible if it was offered during the weekdays. Students also report that they enjoy the weekend format because it requires less in-class time commitment; however, some students have reported Saturday courses to be burdensome.

Student response

Students complete an evaluation at the conclusion of the course, in which they anonymously report what they liked most and least about the course, and also suggest how the course could be improved. Students consistently respond that the service learning project, which facilitates off-campus learning, is the most positive aspect of the course. Students often report during the course evaluation that the ability to have “hands-on experience” is necessary for career development. Students also consistently respond that they appreciate having “speakers from the field” rather than having instruction exclusively from academics.

However, students also report that the service learning component is also the most stressful aspect of the course. Many students, especially undergraduates, have not participated in community-based health work and express frustration at the difficulty communicating with a team of students and with agency representatives. Some students report that developing and implementing a project is extremely challenging. The relatively short duration of the course (eight weeks) and the need to protect the confidentiality of homeless individuals often presents challenges to coordinating projects.

Agency and community response

Most agencies that serve the homeless have been receptive to engaging students in projects and participating in the course. Rarely, agencies have reported being overwhelmed by the volume of students, which may exceed the facility capacity. Agencies usually welcome students but are not immediately comfortable allowing students into the “field.” They usually require students to complete a brief facility orientation and provide education about the psychosocial and health needs of their clients.

Direct service agencies such as HCH and Baltimore Homeless Services nonetheless welcome the involvement of students and have actively identified opportunities for projects that are beneficial to the organization, serve the needs of clients, and provide meaningful education for students. Providers from HCH and other agencies have reported that they value the opportunity to engage in new experiences with students. Providers have also expressed feeling hopeful and optimistic that there are new public health professionals who wish to pursue careers addressing poverty and homelessness. Providers also report that students, as a result of their service experiences, undergo a gradual shift in thinking—often beginning by approaching homelessness from the perspective of “charity” (i.e., what services do people need and how can we provide more of them?) and ending with a greater understanding of “justice” (i.e., what factors are responsible for homelessness in contemporary society and what policies and practices can reduce or end this problem?).

Administrators and providers from HCH and other agencies report looking forward to participating in the course. Through classroom and service-learning interactions, providers have the opportunity to reflect on their work and gain a deeper understanding of the problems that affect homeless populations. Agency managers often identify speakers for the course as professional development opportunities for their employees.

Information collected by students who conduct face-to-face interviews with HCH clients facilitates ongoing performance improvement activities, satisfies grant requirements, and has frequently resulted in changes in agency practice to meet identified needs. Collecting these data is labor intensive and costly for nonprofit organizations, yet is needed to improve services and obtain additional funding to meet service gaps. HCH has reported that being able to rely on students for the collection of these data each year has enabled the organization to focus more resources on client care. HCH has also reported that having the data gathered by unaffiliated and unbiased interviewers increases the likelihood that the results were not inappropriately influenced by the client’s relationship with HCH staff. HCH and other agencies report that projects such as those listed in Figure 2 would not have been accomplished without the assistance of students or would have incurred great cost to the agency. These agencies now annually plan for students to be available to complete these and other new projects.

As a result of annual client satisfaction surveys conducted by JHSPH students, HCH has changed its daily opening times, reduced unnecessary waiting periods, provided additional activities in the waiting room, and redesigned the management of clients within the clinic. Survey results have also informed the design of a planned new HCH facility.

HCH frequently informs other organizations of its collaboration with JHSPH. The HCH board of directors receives an annual report about the course, and HCH frequently discusses the benefits of the course with other organizations locally and nationally. For example, course information has been shared with other HCH projects during the National Health Care for the Homeless Conference and conference organizers are considering a Collaborating with Academia workshop for the 2006 Annual HCH Conference.

LESSONS LEARNED

This collaborative has been successful and sustained for several reasons. A mission of HCH is to prepare future and current health care professionals to work with underserved homeless populations. HCH has been a collaborative partner with JHSPH from the beginning of the course and views the course as essential to meeting its mission. Furthermore, the course instructor and students actively engage agency leaders to determine if students can play a role in meeting their clients’ needs. Service learning projects are not imposed by the instructor or students, but rather emerge from the agency through a process of ongoing dialogue.

An important lesson learned, however, is that participating agencies must annually evaluate their capacity to educate and appropriately utilize the time and talents of students. Periods of staff shortages or unexpected increased agency demands can translate into a poor experience for both the student and the agency. Providing quality service learning activities for students requires time and careful attention from the university and the agency. Students ask questions, require time for consultation and planning purposes, sometimes need to be debriefed, and unfortunately, are not always punctual or reliable, creating frustration for the agency. If this happens too frequently, it can reduce the staff’s willingness to accept students again. Therefore, agency leadership needs to carefully assess the agency and individual staff member capacity to absorb the time required for productive student collaboration.

CONCLUSION

Student feedback and our own observations have led us to conclude that learning about public health problems requires experience outside the traditional academic environment. Students gain invaluable insight and skills by learning from individuals who are homeless, which balances the statistics and jargon that are commonplace in most academic coursework. Our students report that gaining an appreciation for the human reality of homelessness is a necessary complement to academic research.

The course has demonstrated that academia and organizations serving the homeless are capable of sustainable collaboration that simultaneously educates students and serves a vital role in the community. Furthermore, the service learning model used for this course has application to a broad range of health problems and health promotion activities. Schools of public health are well positioned to respond to the needs of their communities by offering structured educational opportunities for students that engage practice partners. Coursework that provides mutually beneficial experiences for students and service providers will prepare students for successful public health careers, increase the positive presence of academia in the community, and ultimately impact the health of vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the individuals who have shared their stories of homelessness as participants in the course and to the dedicated instructors who have volunteered their time: William Breakey, Kathy Becker, Alex Boston, Woody Curry, Maria Foscarinis, Betsy McCaul, Karran Phillips, Thomas O’Toole, Michael Schulte, Betty Schulz, Kelvin Silver, Ross Pologe, and Gwendolyn Richards, among others. The authors also thank the W.K. Kellogg Foundation for providing initial support for the course.

REFERENCES

- 1.McQuistion HL, Ranz JM, Gillig PM. A survey of American psychiatric residency programs concerning education in homelessness. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28:116–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.28.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchanan D, Jain S. Teaching students about health care of the homeless. Acad Med. 2001;76:524–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buttriss G, Kuiper R, Newbold B. The use of a homeless shelter as a clinical rotation for nursing students. J Nurs Educ. 1995;34:375–7. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19951101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cyprus IG, Holleman WL. The homeless visit: enhancing residents’ understanding of patients who are homeless. Fam Med. 1994;26:217–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JA, Martaus TM. Combining community health and psychosocial nursing: a clinical experience with the homeless for generic baccalaureate students. J Nurs Educ. 1987;26:189–93. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19870501-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witt BS. The homeless shelter. An ideal clinical setting for RN/BSN students. Nurs Health Care. 1991;12:304–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masson N, Lester H. The attitudes of medical students towards homeless people: does medical school make a difference? Med Educ. 2003;37:869–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen CI, D’Onofrio A, Larkin L, Berkholder P, Fishman H. A comparison of consumer and provider preferences for research on homeless veterans. Community Ment Health J. 1999;35:273–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1018749504499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenheck R, Lam JA. Homeless mentally ill clients’ and providers’ perceptions of service needs and clients’ use of services. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:381–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK. Comparison of clinicians’ housing recommendations and preferences of homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:413–5. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luck J, Andersen R, Wenzel S, Arangua L, Wood D, Gelberg L. Providers of primary care to homeless women in Los Angeles County. J Ambul Care Manage. 2002;25:53–67. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero L, Heffron WA, Kaufman A. The educational opportunities in a departmental program of health care for the homeless. Fam Med. 1990;22:60–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]