Abstract

Objectives: The objective of this study is to apply J. Richard Hackman's framework on team effectiveness to academic medical library settings.

Methods: The study uses a qualitative, multiple case study design, employing interviews and focus groups to examine team effectiveness in three academic medical libraries. Another site was selected as a pilot to validate the research design, field procedures, and methods to be used with the cases. In all, three interviews and twelve focus groups, with approximately seventy-five participants, were conducted at the case study libraries.

Findings: Hackman identified five conditions leading to team effectiveness and three outcomes dimensions that defined effectiveness. The participants in this study identified additional characteristics of effectiveness that focused on enhanced communication, leadership personality and behavior, and relationship building. The study also revealed an additional outcome dimension related to the evolution of teams.

Conclusions: Introducing teams into an organization is not a trivial matter. Hackman's model of effectiveness has implications for designing successful library teams.

Highlights

Using focus groups and interviews, this research tested the applicability of J. Richard Hackman's framework for team effectiveness in the library setting.

In addition to validating Hackman's original findings related to team effectiveness, participants in this study elucidated additional characteristics of effective teams related to leadership behavior, team building, and communication.

The use of teams in libraries is increasing as the environment of libraries and library practices evolve.

Implications

Hackman's multidimensional model of team effectiveness and outcomes has implications for designing library teams and recruiting employees who will be required to function in a team-based environment.

Libraries using teams should consider the skills needed for these new team-based roles and incorporate questions regarding teamwork and “soft skills” such as communication and listening skills, a willingness to work with others, an ability and desire to take responsibility for decisions, creativity, and flexibility as part of the hiring process.

INTRODUCTION

Budget cuts, staffing shortages, and the rapid growth and deployment of technology have forced a number of libraries to rethink the way they offer services to their patrons [1]. In response to these challenges, many major academic research libraries have restructured their business processes to include groups of individuals or teams that perform the work [2]. Academic medical libraries, though somewhat slower to respond at the time this research was conducted, have started to use teams to accomplish certain tasks. Groups of individuals working together, however, do not necessarily make an effective team. Teams must be planned for and managed [3].

A 1998 survey reported that, during the 1990s, many members of the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) (e.g., University of Arizona, University of North Carolina, University of Minnesota) began to adopt teams [2]. Prior to this time, these libraries were organized by departments and committees according to a strict hierarchy or command-and-control structure [2]. Directors and department heads made decisions that they then communicated to supervisors, who then informed line staff. Shaunessy noted that these managerial layers created slow responses to customer service problems and frustration among library staff [4]. Cross-departmental, multilevel (involving supervisors and staff), and multi-rank (including professionals and nonprofessionals) teams emerged in libraries as a “new way of operating, a new organizational culture” designed to reduce bureaucracy and empower staff [4]. In teams, staff closest to the work proposed and implemented decisions previously made by upper management. Euster [5] referred to this phenomenon as “group empowerment.”

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The introduction of teams in any organization raises the need for ways to promote and evaluate their effectiveness. J. Richard Hackman, Cahners-Rabb Professor of Social and Organizational Psychology at Harvard University [6], takes a multidimensional approach to team effectiveness, positing three defining outcomes and five conditions leading to team effectiveness. These outcomes include (1) a team product that exceeds customer expectations, (2) growth in team capabilities over time, and (3) a satisfying and meaningful group experience for team members. These outcomes result from the five conditions for team effectiveness he specifies:

A real team: Creating the real team is necessary for establishing the foundation for the team's work; the tasks assigned to the team are clear, and members work together;

A compelling direction: Someone in authority tells the team what is expected at the end of their work, but not the means by which the team gets there;

An enabling team structure: Structural features include designing teams with codes of conduct, putting the right people on the team, ensuring the appropriate size and mix of members, and so forth;

A supportive organizational context: A supportive organizational context includes aligning education, information, technical, and reward systems to support teamwork; and

Expert team coaching: Expert coaching refers to facilitating group processes and development [6].

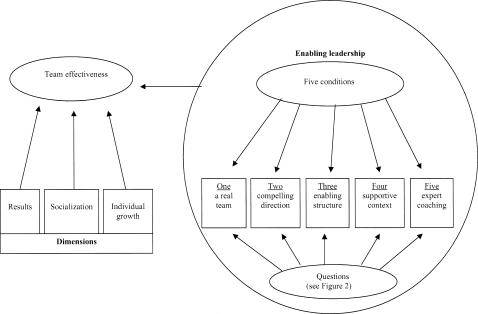

Hackman offers a unique perspective on team effectiveness and outlines an approach for applying his concepts to various organizations (Figure 1). According to him, a leader does not make the team great but rather facilitates the personal, social, and systems conditions that lead to team effectiveness.

Figure 1.

Hackman's framework

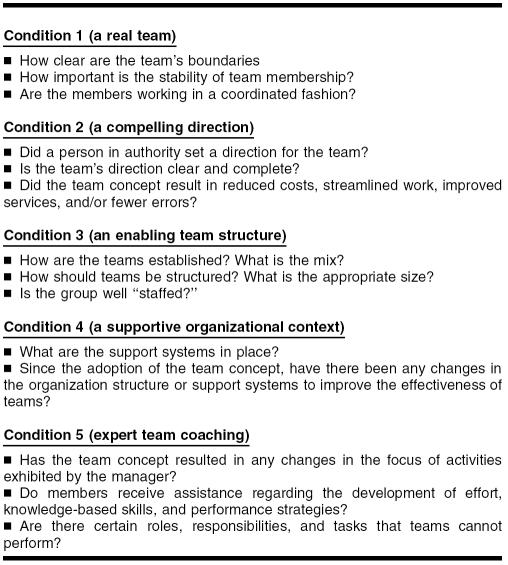

No study has examined Hackman's perspective of team effectiveness in a library setting, medical or other. The purpose of this study is to address the relevance to medical library teams of his five conditions and the set of questions he developed to define the conditions (Figure 2). To what extent do these conditions apply to libraries? Is each condition essential for teams to be effective? Might other conditions prevail? How well do conditions define library teams? The study explores a new dimension to effectiveness that is measured beyond whether or not the team achieves results.

Figure 2.

Hackman's conditions and questions

LITERATURE REVIEW

Definition of teams

Katzenbach and Smith define a team as a “small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, set of performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable” [7]. Alternatively, Kinlaw defines a work group as “a set of two or more job holders who make up some identifiable organizational unit that is considered to be a permanent part of an organization”; whereas, teams are “work groups that have reached a new plateau of productivity and quality” [8]. While Katzenbach and Smith and Kinlaw delineate the differences between working groups and teams, many other researchers disagree and use the terms “teams,” “self-managed teams,” “taskforce,” “project team,” “committee,” and “group” interchangeably. This broad definition follows Hackman's view of teams; he notes: “Although some authors, such as Katzenbach and Smith, take great care to distinguish between the terms teams and group, I do not. I use the terms interchangeably and make no distinction whatever between them” [6].

Teams in libraries

The literature of library and information science (LIS) focuses on how to implement teams in an effort to streamline work processes in academic research libraries and outlines a rationale for doing so after the fact. The LIS literature describes many examples of teams that have failed and succeeded. While the University of Arizona library serves as a model of success [9], the experience at Michigan State University Libraries serves as an example of restructuring that did not go smoothly [10].

Total quality management and reengineering research reported in the LIS literature suggests restructuring through the use of teams leads to increased productivity, increased job satisfaction, and empowerment and development of workers [11]. This trend has been described in early articles highlighting the reorganization of technical services departments into self-managed teams at Penn State University [12] and Yale University [13]. Other articles describe the impact of the use of teams throughout the entire library and issues that arise as a result of the reorganization [4, 14–16].

Team effectiveness

McDonald and Micikas review the various definitions of effectiveness [17]. As they note, there is considerable disagreement in the use of the word, library outcomes, and their measurement as an indicator of effectiveness. The variety in approaches to measuring library effectiveness suggests no simple view has gained universal acceptance, and none is team focused. However, the predominant view of library effectiveness focuses on counting things, such as number of journals and gate counts, and comparing those numbers among a group of libraries. This approach assumes that more is better. Much of the literature regarding team effectiveness focuses on characteristics of design and development of the team in relationship to team outputs and results [18–20]. If the team produces a product, a written report, or reduced cycle time or cost, the team is effective.

METHODS

The methods used in this qualitative, multiple case study include employing interviews and focus groups. Qualitative research is broadly defined as “any kind of research that produces findings not arrived at by means of statistical procedures or other means of quantification” [21]. Qualitative methods produce a wealth of detailed data about a small number of people or cases. The case study takes a real life contemporary situation and provides the basis for applications of ideas, emphasizing detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of situations or conditions and their relationships [22]. Case studies generally address “how” or “why” questions and are often used for studying management problems [22]. Case studies may include one case, where one subject is studied in depth, or multiple cases, where more than one subject is examined. A multiple case study is similar to a single case except the procedures are repeated, thus enhancing the validity and reliability of the findings [22]. This multiple case study examined team effectiveness in three academic medical libraries.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Simmons College and the University of Massachusetts Medical School (the investigator's home institution).

Data sources and site selection

In 2002, the investigator queried subscribers of the mailing list of the Association of Academic Health Sciences Libraries' (AAHSL) about their use of teams. Of the thirty-one responses received, four mentioned that they did not use teams, two responded that they used teams in conjunction with the main library to whom they administratively report, and the remaining twenty-five indicated they used teams some of the time. The investigator made follow-up telephone calls to clarify responses. A closer examination of those libraries that used teams revealed two types of groups: (1) those that used teams for one-time specific projects (e.g., renovation) and (2) those that used teams for the ongoing provision of a specific library service or function (e.g., Website redesign and maintenance). Geographic distribution of all responding libraries using teams revealed the majority were situated on the East Coast. The selected three sites came from the group of libraries that used teams for the ongoing provision of library services.

These libraries were a good match with Hackman's philosophies because the directors were interested in what makes a well-run team, supportive of staff development activities, and supportive of research endeavors. To preserve anonymity, these libraries are referred to as Libraries A, B, and C, respectively.

Pilot site

Another site (Library Z) was selected as a pilot because of its long history with teams despite the fact that it did not have a medical school on its campus. The researcher used the pilot site to validate the research design and troubleshoot field procedures and methods to be used with the cases by conducting an interview with the library director and focus groups with approximately thirty staff who composed the management team, team leaders, and team members. Following the pilot, the investigator discussed the findings with the library director and modified the case study questions and interview script, as necessary.

Selection of teams and participants in focus groups at Libraries A, B, and C

Each of the three sites had four focus groups: department heads or management team (n = approximately 16), team leaders (n = approximately 20), and two groups of team members participated in the groups (total n = approximately 60). The groups overlapped as some participants were both management team members and team leaders or team leaders and team members, because participants played multiple roles across teams and projects. The investigator estimates that a total of seventy-five participants were included across all the focus groups.

The director at each site sent an email to staff explaining the purpose of the researcher's visit and inviting members of all teams, past and present, to participate. Except for the management team group, participants were not predetermined based on job function. Participants were grouped by role in the team; that is, team leaders were together in one focus group and team members together in the other two focus groups.

The team leader and team member groups had a mix of professionals and support staff. Team members did not necessarily have to be on the same team, although some of them had been on teams together. Participation was voluntary. The investigator assured all participants that comments would not be attributed to a particular library or individual.

Data collection methods and analytic procedures

The pilot was conducted in August 2003. One semistructured interview with the director and four focus groups of ninety minutes each were conducted at the pilot site over two consecutive days. Data for the cases were gathered between August and October 2003. In all, three interviews and twelve focus groups were conducted at the case study participants' institutions and were audio recorded.

All focus groups and interviews followed the same format. The researcher provided each person the list of Hackman's conditions and questions (Figure 2). Although questions and topics were predetermined (based on Hackman's set of conditions and questions), the interviews and focus groups were conducted in a semistructured fashion.

Participants were familiar with Hackman's conditions prior to attending the focus group because a description of Hackman's framework was included in the director's invitational email. For the most part, director interviews and focus groups began with the first condition, with participants' verbalizing their reactions to the condition and responses to its applicability and working through the remaining set as listed in Figure 2, although some positions shifted as participants' thoughts spilled into other conditions. Participants used specific examples from teams to clarify points.

The initial sixty-minute structured portion of the focus groups and interviews focused solely on the set of Hackman's conditions, and the investigator probed for participants' responses to the conditions. During the last thirty minutes, the investigator presented the participants with a team-building scenario (Appendix) that she had designed and asked the participants to describe how they would respond to the situation presented in the scenario. Participants related the scenario to their own library's experiences with the presented problem and the ways they solved it using teams. The discussions involving the scenario were less structured and designed to elicit additional conditions that might apply to team effectiveness.

Later, the researcher transcribed the field notes and data recordings and manually organized each transcript according to the five conditions, participant type (e.g., director, team leader, team member, and manager), and characteristics of and barriers to effectiveness by extracting common themes from the collected data. The investigator then constructed tables comparing conditions, facilitators, and barriers across participant groups for each library to facilitate identification of commonalities and differences across informants or focus groups within and across the libraries.

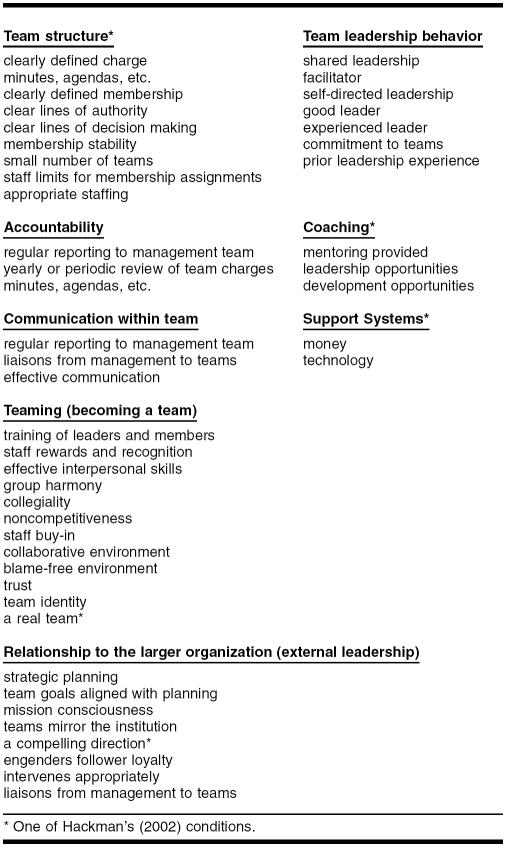

RESULTS

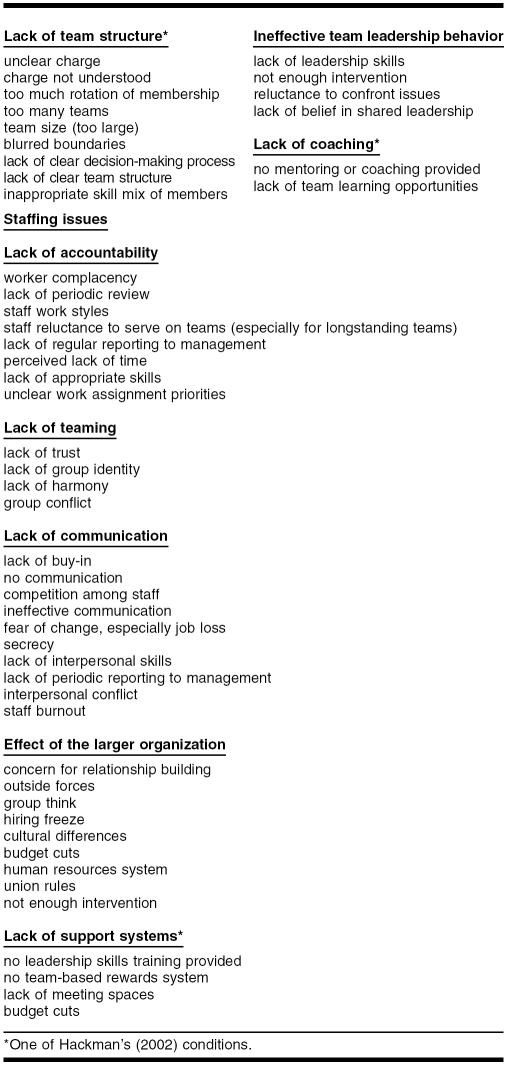

Hackman's view of effectiveness is structural and process oriented. It is based on organization design principles. His premise posits that, if teams are well organized and have the appropriate support systems, they will be effective. The role of the leader is functional, not behavioral. The leader's function is to make sure appropriate conditions are in place for the team. The participants in this study felt this structural approach to team effectiveness and leadership, although applicable to medical libraries, was also limited. They identified additional conditions, characteristics, and barriers to team effectiveness, particularly noting leadership behavior or style as an important missing condition. Figures 3 and 4 provide lists of characteristics of and barriers to effectiveness derived from the data collected in this study and from Hackman's framework.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of effective teams elucidated by study participants

Figure 4.

Barriers to effective teams elucidated by study participants

Library A: characteristics of effectiveness and barriers to effectiveness

The most common characteristics of effective teams, cited by three groups, were a clear yet unrestricted charge and mix of staff. Other common characteristics, cited by two groups, were unstructured teams, innovation, effective communication, self-directed leadership, strong commitment by external leaders, and strong leadership. External leadership sources (director and management team) agreed that a clear yet unstructured charge, a mix of staff, unstructured teams, effective communication, and self-directed leadership were characteristics of effectiveness. Team data sources (leaders and members) agreed that strong commitment by external leaders and strong leadership were characteristics of effectiveness.

The single most common barrier, cited by three groups, was past history or tradition. Other common barriers, cited by two groups, were the human resources system, lack of coaching or succession planning, ineffective or absent communication, unclear charge, lack of training, fear of job loss, and low morale. External leadership sources (director and management team) agreed that the campus human resources system was a barrier to team effectiveness. Team data sources (leaders and members) agreed that the staff's fear of job loss and low morale among the staff were barriers to team effectiveness.

The characteristics of team effectiveness noted by the director and management team present a self-directed view of leadership that asks the staff to share responsibility in leading the library. This view fosters characteristics of effectiveness that do not impose a strong structure or process on teams to encourage innovation and creative ideas. The characteristics also encourage active participation by all staff.

Team members, on the other hand, do not share this view of leadership. Characteristics of effective teams from their perspective center on the more traditional view of leadership and look to a more authoritative structure with respect to teams. While the director and management team identify the need for structure and process as a barrier to effective teams, team members view a lack of structure as lack of direction and lack of leadership.

Library B: characteristics of effectiveness and barriers to effectiveness

All data sources agreed that a clearly defined charge and effective external and internal communication were two characteristics of team effectiveness. External leadership data sources (director and management team) also agreed that mix of staff and trust were characteristics of effective teams. Team data sources (team members and leaders) agreed that having clear lines of authority and decision making was a characteristic of team effectiveness. Data sources did not note one common barrier to team effectiveness or agree on barriers across all data sources. However, the director and team leaders agreed on one barrier—staff burnout.

The characteristics of team effectiveness noted by all groups in Library B focus on relationship building and leadership behavior. Loyalty, collegiality, communication, listening, and grace are cited as facilitators to team effectiveness. Barriers to effective teams focus on the lack of these relationship-building characteristics and leadership behaviors. The participants in Library B agree that a leader's ability to listen, communicate, and behave kindly affects overall team performance. This view is missing from Hackman's set of questions and conditions.

Library C: characteristics of effectiveness and barriers to effectiveness

The most frequently mentioned effectiveness characteristic—shared by the director, team members, and team leaders—was a clear charge. All groups mentioned lack of support and training for teams as a major barrier. Team data sources (leaders and members) agreed that teams with overlapping responsibilities were also a barrier. External leadership data sources (director and managers) did not agree on any barriers.

Although respondents feel that Hackman's conditions apply to their setting, they identify thematic gaps. Internal communication, trust, mission consciousness, interpersonal skills, a clear decision-making process, and internal team leadership are characteristics of team effectiveness that Hackman does not mention. In addition, he does not address the issue of teams in a hierarchical structure or the dual role of team leadership and department head that exists in Library C.

DISCUSSION

Characteristics of effectiveness

The characteristics of effectiveness that emerged from this study can be divided into eight categories: (1) team structure, (2) accountability, (3) communication, (4) teaming (becoming a team), (5) relationship to the larger organization, (6) leadership behavior, (7) support systems, and (8) coaching. Hackman's framework includes team structure, support systems, and coaching. Two other conditions (a real team and a compelling direction) are subsumed under new categories. Accountability, communication, teaming, relationship to the larger organization, and leadership behavior are missing from Hackman's set of conditions. Figure 3 defines the specific characteristics of effectiveness and lists them under their broad headings.

Barriers to effectiveness

Barriers to effectiveness can be divided into nine categories, largely opposite to the effectiveness categories noted above: (1) lack of team structure, (2) lack of accountability, (3) lack of communication, (4) lack of teaming, (5) effect of the larger organization, (6) ineffective leadership, (7) lack of support systems, (8) lack of coaching, and (9) staffing issues. Figure 4 illustrates the specific barriers and lists them under their broad headings.

Outcomes dimensions

In addition to elucidating a new set of conditions, effectiveness characteristics, and barriers, participants expanded on Hackman's definition of effectiveness outcomes. Hackman's definition of effectiveness includes three dimensions (results, socialization, and personal growth). Study participants agreed with this multidimensional definition. Effective teams resulted in new services, improved services, or remodeled facilities. Team members from different departments worked well together inside and outside the team. Many team members and leaders gained new skills and broader responsibilities as a result of their experience on a team. However, participants cited another dimension to effectiveness: effective teams evolved over time. Teams are organic with a life cycle. They began in these libraries under one format and changed over time as members and leaders became more experienced.

Hackman's view of leadership

Hackman's view of leadership is functional and enabling rather than behavioral. Focus group participants viewed this definition of leadership as limited. They emphasized good leadership behaviors, personality, and leadership style as characteristics of effectiveness. They wanted leaders to intervene when there was conflict or when a team was struggling. The directors, on the other hand, did not always share this view as they wanted teams to manage themselves and share the responsibility of leadership.

Although all participants were extremely positive about the use of teams, informants could name at least one problematic team; the problem team was consistently mentioned by all the groups in a particular site. Problems often focused on lack of team structure, lack of leadership, and unclear lines of authority. Similarly, across the board, participants could list more barriers to effective teams than facilitators. Team members consistently identified the highest number of barriers. Team leaders universally identified the need for more team leadership training skills and more coaching. Some leaders were hesitant about assuming the authority given to them by library directors, while others assumed too much authority over the team and did all the work.

Directors consistently expressed the desire for more shared leadership and decision-making responsibility assumed by the team. They cited the reluctance by team leaders and members to address conflicts in the team as particularly problematic. Some mentioned the team's desire for director intervention when a team was struggling as particularly troublesome.

It is clear that directors form teams to involve staff in the decision-making process; however, many team leaders and staff are uncomfortable in their new roles. Leaders and staff emphasized collegiality, group harmony, and “getting along” as important characteristics of effective teams. They were unwilling to confront members who did not perform due to the risk of disrupting workplace friendships. In the end, however, this unwillingness to confront conflict ultimately led to a failed team.

Study limitations

This study was a doctoral research project testing a theoretical framework for team effectiveness and its applicability to medical libraries. Because focus group participants could relate experiences from one or more teams, past and current, the analyzed data were self-reported and limited by recall. Additional documents such as team meeting minutes, also self-reported, added no new information. Time constraints, travel limitations, and lack of financial resources limited the number of libraries included in the study to three. The author was the sole researcher gathering the data, transcribing the tapes, and analyzing the data; therefore, there was no intra- and inter-rater comparison for reliability.

CONCLUSION

Based on the investigator's discussions with AASHL directors, the medical libraries that have transitioned their organizational structures to include teams are limited in number, but growing, since this study. The rationale for this shift has been the changing factors in the environment (e.g., rising serial prices, budget cuts, new technologies, etc.) [1]. Many library directors realize that in order to adapt to this rapidly changing environment, business processes must focus on the customer and staff need to participate in the decision making [2]. This creates new, more participatory roles for everyone in the library [4, 5].

Hackman [6] identified five conditions leading to team effectiveness and three outcomes dimensions defining effectiveness. The participants in this study identified additional characteristics of effectiveness that focused on enhanced communication and identifying personality and behavioral characteristics of team leaders and team members that foster team building and discourage internal conflict. Relationship building and fostering collaboration, collegiality, and harmony are also new. The importance of these additional characteristics is consistent across all the libraries included in this study.

Hackman's model of effectiveness and outcomes has implications for designing library teams and recruiting employees who will be required to function in a team-based environment. Library directors and department heads using teams in their libraries to share decision-making responsibility among staff need to consider the skills necessary for these new team-based roles and incorporate questions regarding teamwork as part of the hiring process. Library search committees need to screen applicants not only for the appropriate technical skills required for a position but also for the “softer skills” needed for effective team-based work [23]. These skills include excellent written and oral communication skills, a willingness to work with others, an ability and desire to take responsibility for decisions, good listening skills, creativity, and flexibility.

Library directors considering the adoption of teams can learn from their colleagues' experiences. The challenge remains in sustaining teams and making them effective. Questions remain as to how well teams work, why some fail, and why other teams thrive. The libraries in this study provide insights into the conditions for, characteristics of, and barriers to, effective teams. Hackman's model and the additions to his framework provided by the study participants can be among the first steps in learning how to form effective teams.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks her doctoral advisor, Peter Hernon, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, Simmons College, Boston, Massachusetts, for his assistance in reading early drafts of this manuscript and for his editorial comments. The author also thanks the library staff at Libraries A, B, C, and Z who so generously gave of their time to participate in this study.

APPENDIX

Scenario

Library X is a medium-sized academic health sciences library serving faculty, staff, and students in a school of medicine, school of nursing, and adjoining hospital. The library subscribes to 1,000 print journals and more than 2,000 electronic full-text journals. Total monographs include 65,000, and print volumes are 225,000. The library's annual budget is approximately $3.7 million with $1.8 million spent on acquisitions. Staff totals 38 full-time equivalents (FTEs), with a mix of 18 professionals and 20 support staff.

Traditional print, networked databases, and full-text resources are available but are often difficult for users to find. The library was providing two different approaches to these materials. The first was an online catalog for holdings information for the print collections through an integrated library system, maintained in technical services by two professional catalogers. The second was a list of full-text journals and databases through the library's Website, maintained by the library's Web manager, a member of the systems department. A proxy server allowed access to resources through the library's home page for offsite users.

One weekend, the library Web server crashed, disabling access to the full-text resources for three days (until the Web server could be restored). Because the Web server and the integrated library system, which housed the online catalog, were on different servers, access to the print collection via the online catalog continued to be available. This event caused the library staff and managers to agree that multiple access points for both print and electronic resources were needed; however, they disagreed about an approach.

How would a team be established in your environment to address this issue? How would the team function? How would the team be staffed? Please describe the team direction, team membership, leadership roles, reward systems, outcomes, and so on.

Footnotes

* Based on doctoral dissertation of the same name, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, Simmons College, Boston, Massachusetts, December 2004.

REFERENCES

- Giesecke JR.. Reorganization: an interview with staff from the University of Arizona Libraries. Libr Admin Manage. 1994;8:196–9. [Google Scholar]

- Soete G. The use of teams in ARL libraries, spec kit 232. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Biolos J. Six steps toward making a team innovative. In: Results driven manager series: teams that click. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shaunessey T.. Lessons from restructuring the library. J Acad Libr. 1996;22:251–7. [Google Scholar]

- Euster JR.. Teaming U. Wilson Libr Bull. 1995;69:57–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman JR. Leading teams: setting the stage for great performances. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenbach JR, Smith DK.. The discipline of teams. Harvard Business Rev. 1993;71:111–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlaw DC. Developing superior work teams: building quality and the competitive edge. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz JR, Pintozzi C. Helping teams work: lessons learned from the University of Arizona Library reorganization. Libr Admin Manage. 1999 Winter; 13(1):27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Echt R. The realities of teams in technical services at Michigan State University Libraries. Library Acquisitions: Practice and Theory. 1997 Summer; 21(2):173–8. [Google Scholar]

- deJager G, duToit AS.. Self directed work teams in information services: an exploratory study. South African J Libr Inform Sci. 1997;65:1948. [Google Scholar]

- McAdam T, Stanley NM.. Implementing teams for technical services functions. The Serials Librarian. 1996;28(3/4:):361–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell GR, Sullivan M.. Self-management in technical services: the Yale experience. Libr Admin Manage. 1989;3:20–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bender L. Team organization—learning organization. the University of Arizona four years into it. Information Outlook. 1997 Sep; 1:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers M, DeBeau-Melting L, DeVries J, Schellinger M.. Organizational restructuring in academic libraries: a case study. J Libr Admin. 1996;22(2/3):133–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MJ. Taking time for the organization. Coll Res Libr News. 2001 Oct; 62(9):900–8. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JA, Micikas LB. Academic libraries: the dimensions of their effectiveness. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mickan S, Rodger S. Characteristics of effective teams: a literature review. Australian Health Rev. 2000 Jul; 23(3):201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey M. Work teams: three models of effectiveness. [Web document]. Denton, TX: University of North Texas Center for the Study of Work Teams, 1998. [cited 13 Apr 2006]. <http://www.reedsresearch.com/TeamFormation-files/workteamstudy.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Larson CE, La Fasto F. Teamwork: what must go right/what can go wrong. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. Case study research design and methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cauldron S. The hard case for soft skills. Workforce. 1999 Jul 1; 78:60–7. [Google Scholar]