Abstract

Setting: Purdue University is a major agricultural, engineering, biomedical, and applied life science research institution with an increasing focus on bioinformatics research that spans multiple disciplines and campus academic units. The Purdue University Libraries (PUL) hired a molecular biosciences specialist to discover, engage, and support bioinformatics needs across the campus.

Program Components: After an extended period of information needs assessment and environmental scanning, the specialist developed a week of focused bioinformatics instruction (Bioinformatics Week) to launch system-wide, library-based bioinformatics services.

Evaluation Mechanisms: The specialist employed a two-tiered approach to assess user information requirements and expectations. The first phase involved careful observation and collection of information needs in-context throughout the campus, attending laboratory meetings, interviewing department chairs and individual researchers, and engaging in strategic planning efforts. Based on the information gathered during the integration phase, several survey instruments were developed to facilitate more critical user assessment and the recovery of quantifiable data prior to planning.

Next Steps/Future Directions: Given information gathered while working with clients and through formal needs assessments, as well as the success of instructional approaches used in Bioinformatics Week, the specialist is developing bioinformatics support services for the Purdue community. The specialist is also engaged in training PUL faculty librarians in bioinformatics to provide a sustaining culture of library-based bioinformatics support and understanding of Purdue's bioinformatics-related decision and policy making.

Highlights

Purdue University is rapidly undergoing a metamorphosis to a major interdisciplinary and applied life science research institution that brings with it a system-wide shift in research toward bioinformatics and new bioinformation needs.

The molecular biosciences specialist developed a two-tiered bioinformation needs assessment strategy, which combined gathering qualitative observational data from working in context at the point of practice with quantitative survey data.

Bioinformatics Week, a compact and intense series of bioinformatics lectures and workshops, was organized by the specialist to meet immediate needs campus-wide, while simultaneously serving as “proof of concept” for developing new in-house bioinformatics services.

The success of the evaluation and assessment program, combined with the knowledge that bioinformatics information needs are continuing to increase, led to the creation of the Purdue Libraries' Bioinformatics Initiatives Group, which will plan and develop future system-wide bioinformatics services.

Implications for practice

Combining qualitative information needs data with quantitative data can remove assumptions during decision-making processes involved in developing and maintaining library services.

Engaging in context at both the enterprise and individual levels is key to understanding drivers of organizational information needs and to developing anticipatory bioinformatics services.

Engaging with the client community is critical to identifying and overcoming barriers to developing sustaining partnerships between librarians and subject faculty.

INTRODUCTION

Bioinformatics research advances in such areas as gene therapy, personalized medicine, drug discovery, the inherited basis of complex diseases influenced by multiple gene/environmental interactions, and the identification of the molecular targets for environmental mutagens and carcinogens have wide ranging implications for the medical and consumer health sectors. Librarians have taken a lead in developing library-based bioinformatics resources and programs [1–14] that expand librarians' roles by placing them at the point of origin of bioinformatics information needs. A natural extension of the medical/clinical informationist [15–22], the bioinformationist [23, 24] would integrate bioinformatics librarians [25–28] directly into the practice environment of the research laboratory.

This paper provides a preliminary discussion of steps taken by the Purdue University Libraries (PUL) toward a bioinformationist service and strategies for initiating molecular biosciences services through eighteen months of continual assessment of user needs and research practice at Purdue.

BACKGROUND: THE PURDUE LIBRARIES MOLECULAR BIOSCIENCES SPECIALIST

In 2002, the PUL hired a molecular biosciences specialist with both a master's of library science and doctoral degree in developmental biology and more than fifteen years experience as a bench molecular biologist to:

meet the molecular biosciences information needs of all PUL clients, regardless of individual library affiliation

collaborate with other PUL faculty with liaison responsibilities in agriculture, science, pharmacy, and veterinary medicine

adopt new technologies and implement new molecular biosciences services and procedures

provide reference service and one-on-one instruction in both traditional and virtual environments

lead in defining and implementing molecular bioscience user instruction

support the libraries system-wide efforts through teams and committees

The specialist began an initial process of environmental scanning and needs assessment to inform the development of bioinformatics support services.

DEVELOPMENT OF BIOINFORMATICS INFORMATION SERVICES “IN-CONTEXT”

Stage 1: Developing a strategy

On arriving at PUL early in 2003, the specialist decided that developing library services in context initially meant entering the user community to:

understand Purdue's institutional factors and structures that would drive and/or hinder library services in the molecular biosciences

delineate what constituted “molecular biosciences” research at Purdue through a proactive dialogue with subject faculty

develop a sense of laboratory research workflow and practice by integrating into research laboratories

confirm conclusions drawn from in-context assessment through the implementation of tools to quantify user needs prior to planning library services

develop and implement a prototype molecular biosciences service followed by another round of assessment before proceeding further

Stage 2: Assessing information needs in-context

As part of this multistep strategy, the specialist's initial efforts were spent observing and recording information needs in context in the bioresearch community to analyze the rapidly changing information needs both at Purdue and in the bioinformatics research discipline. To understand Purdue's institutional culture, research workflow, and types of research conducted, the specialist engaged in university strategic planning sessions related to the molecular biosciences, while simultaneously developing working relationships with individual faculty. The latter included integrating into a practicing bioinformatics research laboratory to observe needs in action. Interviewing two chairs of major life sciences departments helped gather information and led to key interviews with additional bioresearcher stakeholders who had increasing biomolecular science information needs. Only from observing practice in context were the nuances of changing bioinformatics needs uncovered. These subtleties would later drive PUL's decisions related to bioinformatics services and products. Key insights gained from this period of assessment and integration included the following:

A new university research culture

The overarching conclusion drawn by the specialist was that Purdue, traditionally perceived as an agricultural and engineering research university, was aggressively undergoing a rapid metamorphosis under new leadership and a new strategic plan to a major interdisciplinary biomedical and applied life science research institution as well. New information needs were arising for an established faculty as they began to engage in unfamiliar biomedical research areas. The strategic plan's expectation that all academic units, including PUL, would engage in an entrepreneurial environment—a significant cultural and philosophical shift from past practice—strongly influenced the specialist's planning and strategies.

A paradigm shift in bioresearch practice

A second major insight was the realization that bioinformatics research was expanding outward from the biomedical science subject areas into such disciplines as chemistry, physics, agriculture, engineering, and psychology as the strategic plan drove interdisciplinary research alliances across traditional professional boundaries. Once a descriptive and observational science, bioresearch is becoming a predictive science at Purdue. Searching bioinformatics databases is thoroughly integrated into the biomedical research cycle. The standard research progression of hypothesis, experimental testing, and literature publication through peer consensus building has now given way to bioinformatics research dealing directly with data divorced from context and meaning and accessed over the Internet.

Exponential amounts of information

Clients regularly communicated that they greatly needed help working with bioinformatics resources. Particularly, researchers expressed frustrations about the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST), the major search algorithm used in bioinformatics to query for gene and protein sequences of interest. The sheer number of bioinformatics databases, their often redundant and overlapping content, their dispersal throughout the Internet, their large datasets, their growing complexity, and their constant rearrangement to hold new data and information had outpaced the ability of bioresearchers to locate, identify, and develop sufficient expertise in the bioinformatics resources they needed.

Critical development of trust

The specialist had to establish a reputation as a problem solver before clients became comfortable communicating their bioinformatics information needs. Regularly dealing with such issues as proxy server problems or locating electronic journal articles were critical in gaining client confidence. Underlying this phenomenon were clients' perceptions of what librarians and libraries do. Actively marketing PUL and helping to visualize the practice of librarianship for clients, the individual expertise of Purdue librarians, the library as a whole, and the value of library and information science as a profession, was essential.

Conveying the value of librarianship

In part because faculty did not know the specialist had been a practicing bench scientist who held a doctoral degree, they often expressed doubt about librarians' abilities to understand the content and context of active bioinformatics research practice. Scientists are healthy skeptics who train others to be healthy skeptics, continually evaluating and retesting original conclusions as a community of practice when new information arrives. After faculty had begun to accept and trust the specialist, they still challenged the need for librarians to partner and work with science subject faculty. The specialist realized that, because the direction that PUL was taking was new, it could be viewed from the culture of science as an experiment. The specialist usually was able to effectively counter faculty's arguments by noting that, although results probably could not be predicted, their commitment to see the experiment through could lead to new approaches, propel new paradigms, and provide insight into the needed contributions of librarians.

The specialist also identified that different mechanisms with which the cultures of science and librarianship educate (credential) their professionals meant that clients did not realize that library and information science (LIS), like educational tracks for lawyers and masters' of business administration, does not have master's and doctoral educational programs “inline” as science does. Once the author was able to describe the educational process in LIS as generally splitting into practice (master's of library science or librarianship) or theory and research (doctoral degree), faculty understood and accepted the rationale that LIS disciplines credential their professionals as effectively as science does. This hindrance to accepting librarian faculty credentials essentially abated after the library-sponsored Bioinformatics Week, a campus-wide bioinformatics instructional program that resulted from the author's working in context with the bioresearch community.

These insights set the stage for the next phase of developing an understanding of bioinformatics needs at Purdue, a formal needs assessment.

Stage 3: Assessing information needs

Although all of the information gathered in context by the specialist seemed to point to the fact that there were considerable bioinformatics information needs spread across a large number of scientific subdisciplines at Purdue, this was anecdotal evidence not grounded in quantifiable data. Moreover, the nature of the information needs had to be further detailed to develop effective strategies. The specialist undertook two surveys to validate these anecdotal needs as well as to provide data to match needs to specific instruction. A preliminary summary of the salient results is presented below.

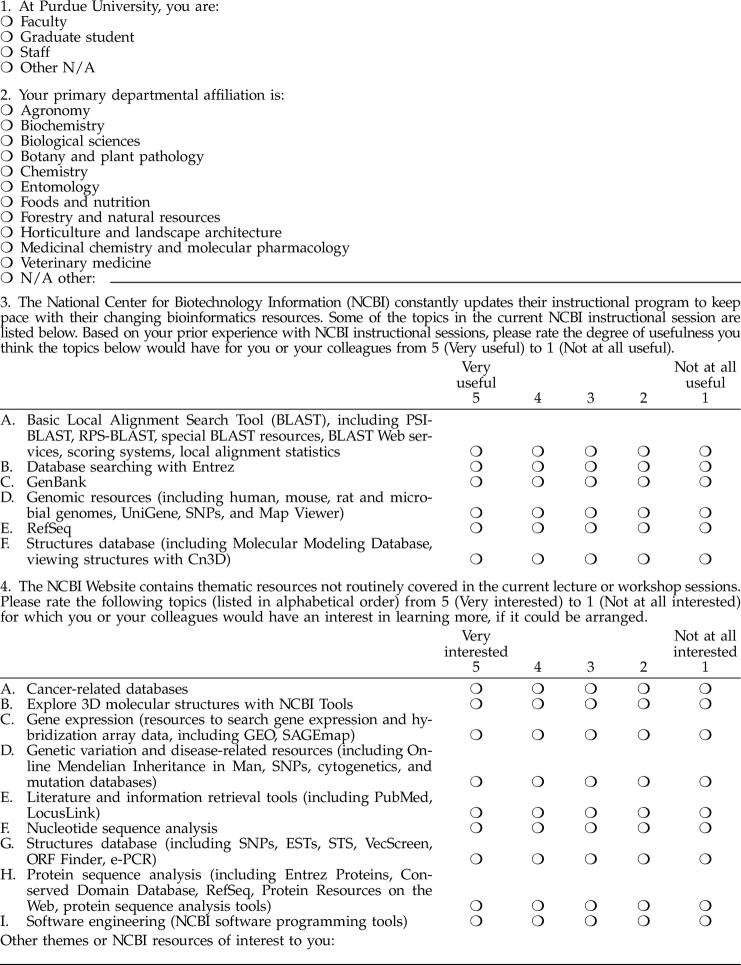

May 2004 survey

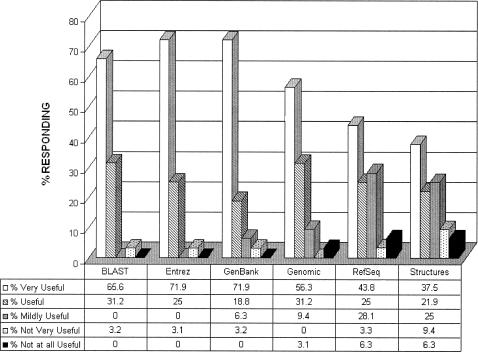

In May of 2004, the specialist retrospectively polled those 108 faculty, staff, and student attendees of the “National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Field Guide” workshop and lecture <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Class/FieldGuide/> held at Purdue in 2002. The Web-based survey (Appendix A, available online only) aimed to determine how effectively the “Field Guide” subject areas had met bioinformatics needs in 2002 as well as to uncover current information needs. Thirty-five participants responded (32.4% response rate), generally indicating that the NCBI databases covered in the “Field Guide” continued to be highly valued two years later (Figure 1) and that instructional needs in these areas continued to be important to Purdue bioinformatics researchers in 2004.

Figure 1.

Ratings of the degree of usefulness of the 2002 National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) “Field Guide” topics (May 2004)

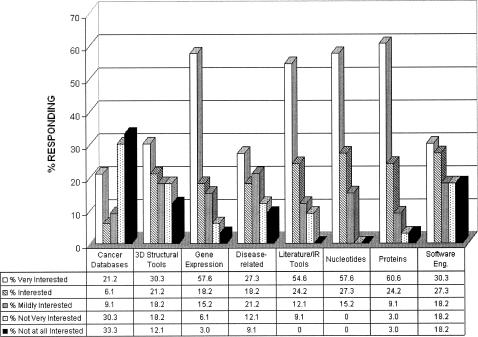

The survey also (Figure 2) asked respondents to indicate interest in topical resources not covered in the “Field Guide,” but currently available at NCBI or at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI). Results showed a high degree of interest for additional bioinformatics instruction in gene expression, literature and information retrieval tools, nucleotides, and protein resources. Considerable interest in microarray, proteomics, and software engineering resources was also indicated. Similar results were observed for questions regarding equivalent resources at EBI (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Ranking of NCBI resources with respect to respondents' bioinformatics information interests (May 2004)

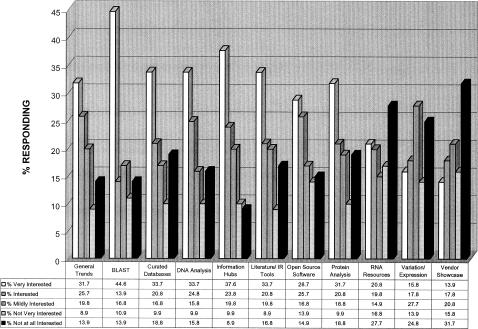

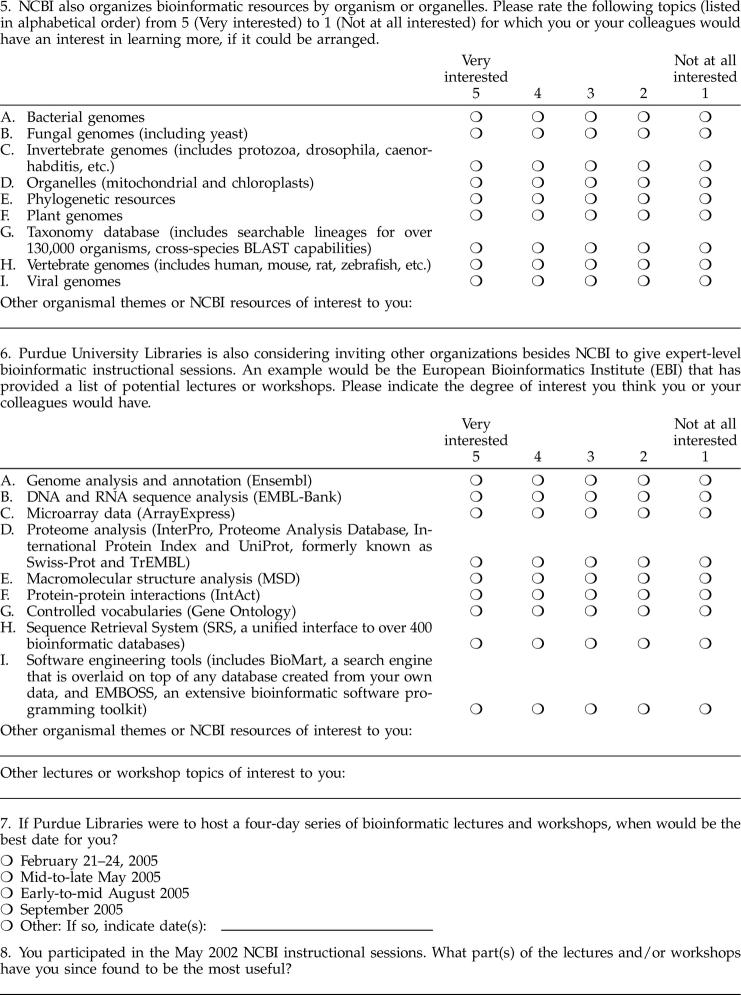

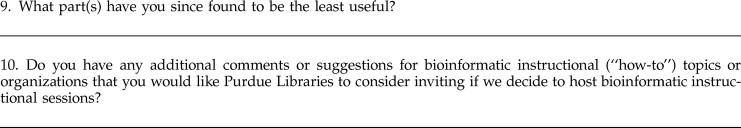

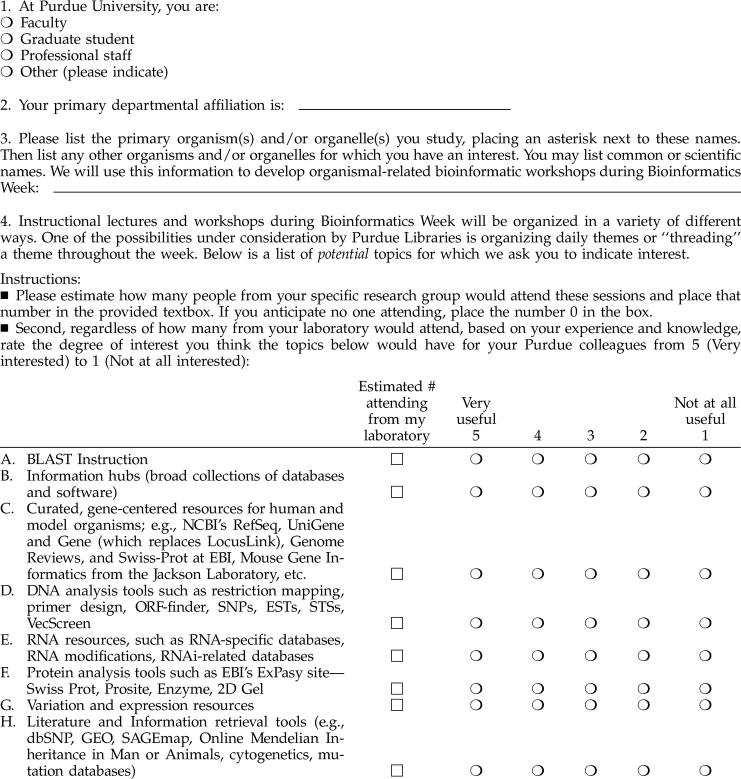

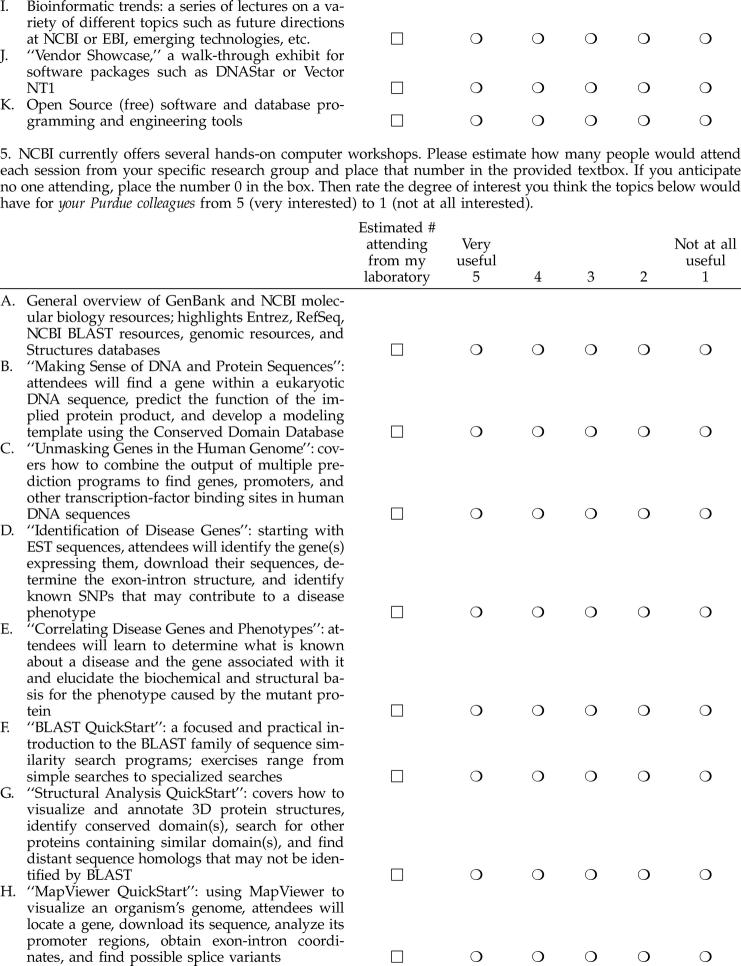

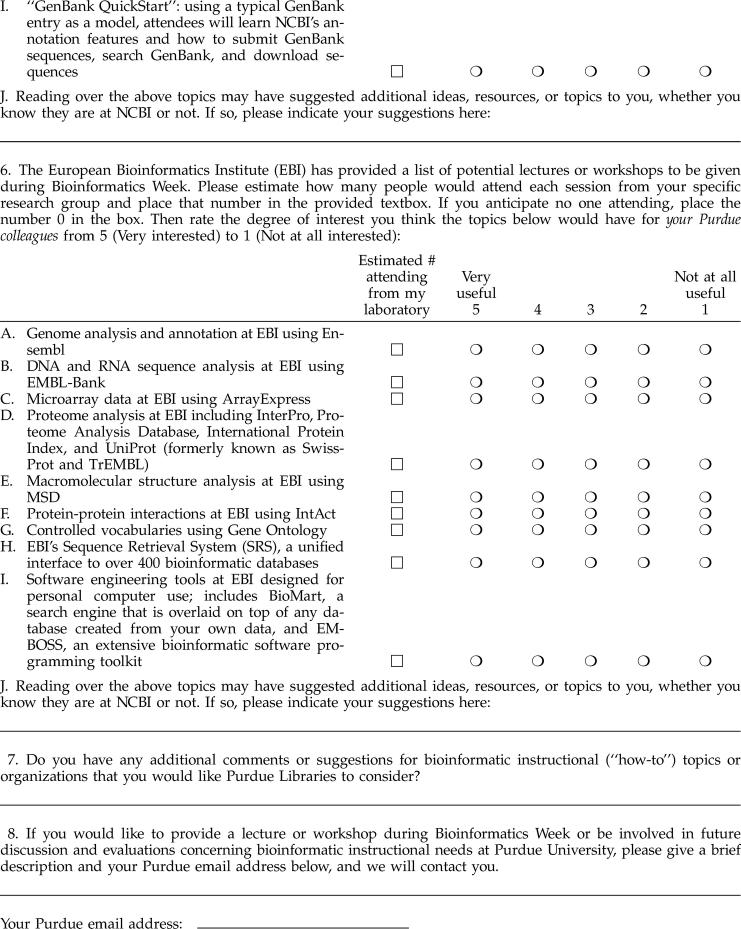

September 2004 survey

To address the issues raised in the initial survey and to poll a wider audience, the specialist conducted a follow-up, Web-based survey in September 2004 (Appendix B, available only online), which was distributed to 858 Purdue faculty potentially interested in bioinformatics research and/or teaching from 43 different departments. This faculty-only survey also asked recipients to indicate how many individuals from their research laboratories would attend any potential bioinformatics instructional sessions. These data would help PUL rank priorities and develop a key action plan with respect to bioinformatics services and resources.

One hundred and thirty six faculty (15.9%) from thirty-six departments responded, strongly suggesting that bioinformatics instructional needs did indeed span bioresearch practice throughout Purdue. Figure 3 illustrates respondents' degree of interest in potential bioinformatics instructional themes, products, and/or resources. Generally, over half of respondents were interested in BLAST, DNA and protein analyses, curated databases, understanding general bioinformatics trends and information hubs, and software development tools. Results typically followed the pattern of results of the prior survey. Moreover, results collected on degree of interest in specific EBI and NCBI databases also corroborated the general trend, lending validity to the overall results from both surveys.

Figure 3.

Follow-up survey rankings of NCBI resources with respect to respondents' bioinformatics information interests (September 2004)

Stage 4: Initiating the Purdue Libraries bioinformatics program: Bioinformatics Week

Integrating in context throughout the university, the specialist had identified that bioinformatics practice appeared to extend across the Purdue campus. Based on a preliminary evaluation of subject faculty publications and the references cited in those publications, the specialist estimated that at least 100 Purdue subject faculty were either working directly in and/or accessing bioinformatics resources as an integral part of their research. The results of the two surveys corroborated this conclusion and identified that additional clients in many subject disciplines, with no prior exposure to bioinformatics research and tools, had a growing and immediate need for basic bioinformatics instruction, as they moved to engage in new interdisciplinary research efforts with more experienced Purdue bioinformatics researchers.

The specialist also decided that PUL would have maximum impact and exposure in mounting bioinformatics services and instruction if the initial launch of library-based bioinformatics instruction were to be offered in a compact, highly visible program that addressed common bioinformatics needs across the widest client audience possible. The concept of an instructional “Bioinformatics Week,” hosted by PUL, was developed to formally launch library-based bioinformatics instruction, while providing proof of concept for future services.

The extent of bioinformatics information needs, as well as the sense of urgency to deliver bioinformatics instructional services as soon as possible, clearly outstripped the ability of a single biomolecular sciences specialist. To remedy this problem, the specialist formed the Purdue Libraries Bioinformatics Initiatives Group (BIG) <http://www.lib.purdue.edu/life/BioinformaticsWeek2005/big.html>, an ad hoc bioinformatics planning group composed of six volunteer science librarians. The group's immediate work included planning and handling the logistics involved in hosting Bioinformatics Week and embarking on an active educational program to bring sustaining bioinformatics expertise to BIG members.

Bioinformatics Week 2005

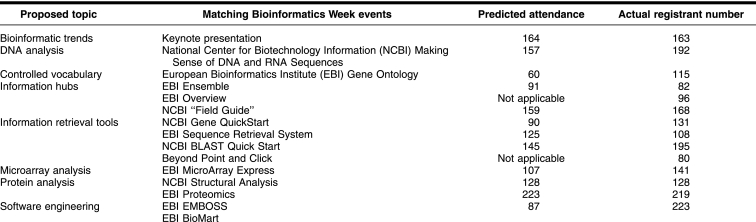

Using the surveys as a blueprint, BIG began the process of mapping the results to specific bioinformatics instructional modules that could be given during a campus-wide week of intense bioinformatics instruction (Table 1). Emphasis was placed on providing hands-on workshops with content that the surveys indicated had the widest audience. Based on the survey results, BIG identified NCBI and EBI as the primary organizations offering both content and instructional levels that most closely matched Purdue's bioinformatics information needs.

Table 1 Bioinformatics week topics and attendance

Two modules, an advanced BLAST workshop and an EBI resource overview were added to fill instructional gaps implied from an analysis of the survey results. Most of the sixteen developed instructional modules had lecture and related workshop components. Expert-level instructors were chosen primarily from NCBI and EBI. To frame Bioinformatics Week, a keynote speaker was added and Purdue's provost agreed to formally open the event. Finally, a Bioinformatics Week Website <http://www.lib.purdue.edu/life/BioinformaticsWeek2005/> was developed to disseminate information about Bioinformatics Week and register participants.

Two hundred seventy-eight Purdue participants from 31 departments participated in Bioinformatics Week training sessions. As predicted, the audience was primarily graduate students (51.8%, N = 144) with a significant number of faculty (34.9%, N = 97) and postdoctoral fellows (13.9%, N = 20) also enrolling. The average participant registered for 8 different modules, with most lectures seating more than 100 participants. Working with the instructors, BIG was able to add additional workshop sections to handle significant waiting lists. Overall, the second survey accurately predicted enrollment levels (Table 1), though the number of enrollees for the Gene Ontology and software engineering modules was almost 3 times more than expected, indicating emerging instructional needs.

Bioinformatics Week demonstrated the need for bioinformatics instruction and raised awareness of PUL's ability to provide bioinformatics support. Data gathered in the needs assessments, follow-up surveys of Bioinformatics Week participants, and insights gained from implementing Bioinformatics Week will provide a strong foundation for the development of responsive services to support Purdue's bioinformatics research.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Working in context with clients system-wide to generate a subjective evaluation of information needs and generating quantifiable data through survey assessment or evaluation tools have been particularly powerful strategies leading to the development of bioinformatics information services at PUL. The strategies revealed that bioinformatics informational needs at both the enterprise and individual bioresearcher levels were changing at an exponential rate as a result of Purdue's strategic planning.

The need to proactively market the value of librarianship was an unanticipated finding. Through an active marketing campaign involving newspaper and television articles, Bioinformatics Week 2005 achieved a high level of recognition for PUL, its librarians, and librarianship in general. One of the direct outcomes of Bioinformatics Week 2005 was the creation of a university-wide Bioinformatics Working Group by the Office of the Vice President for Research, which two Purdue librarians, including the specialist, were asked to join.

Bioinformatics Week 2005 was also the launch point for bringing instructional expertise in bioinformatics to BIG. Currently, the specialist has developed a series of internal instructional modules to foster BIG librarians' development of sufficient bioinformatics expertise to provide a sustaining culture of planning, policy setting, and managing bioinformatics informational needs at Purdue. Preliminary analysis of a survey of participants of Bioinformatics Week 2005 indicated an expectation that PUL will now provide year-round bioinformatics instructional support for Purdue clients. As a consequence, several BIG members also are moving forward to develop expertise in sequence similarity searching, structural visualization, and bioinformatics literacy and pedagogy.

One of the challenges BIG faces is not to become complacent. Purdue bioresearchers are already moving into new bioinformatics areas. Developing bioinformatics services brings with it the challenge of continual evolution and metamorphosis to maintain enterprise-level engagement, create new evaluation and assessment tools, anticipate individual clients' needs, and develop novel and innovative bioinformatics instructional and information devices.

Acknowledgments

A very special acknowledgement is extended to newly appointed Dean of Purdue Libraries James L. Mullins, who proactively supported, listened to, and trusted his librarians and fully embraces developing in-context information services. In addition, the author gratefully acknowledges those Purdue University librarians who taught, advised, and counseled her throughout the process of working in context, ultimately banding together to form the Bioinformatics Initiatives Group: Sarah Kelly, former head, Life Sciences Library; Vicki Killion, division head, Health and Life Sciences; Gretchen Stephens, head, Veterinary Medical Library; Jane Kinkus, head, Mathematical Sciences Library; Charlotte Erdmann, engineering librarian; and Bartow Culp, head, M. G. Mellon Library of Chemistry.

APPENDIX A

Survey 1: The Purdue University Libraries “National Center for Biotechnology Information Field Guide” retrospective survey

APPENDIX B

Survey 2: The Purdue University Libraries 2004 bioinformatic instructional needs at Purdue survey

REFERENCES

- Yarfitz S, Ketchell DS. A library-based bioinformatics services program. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Jan; 88(1):36–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei PP, Martinez JP. Gateway to bioinformatics: the Internet. Med Ref Serv Q. 1996 Summer; 15(2):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Delwiche FA. Introduction to resources in medical genetics. Med Ref Serv Q. 2001 Summer; 20(2):33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower C. Science and technology sources on the Internet: guide to selected bioinformatics Internet resources. Issues Sci Technol Librariansh [serial online]. 2002 Winter. [cited 13 Oct. 2005]. <http://www.istl.org/02-winter/internet.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp BA, Wheeler DL. Bioinformatics resources from the National Center for Biotechnology Information: an integrated foundation for discovery. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2004 Mar; 56(5:):538–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang KS. Biology databases for the new life sciences. Sci Technol Lib. 2004 Nov; 25(1/2):139–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch C. Medical libraries, bioinformatics, and networked information: a coming convergence? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1999 Oct; 87(4):408–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMullen WJ, Denn SO. Information problems in molecular biology and bioinformatics. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2004 Mar; 56(5):447–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stankus T. Making sense of the next big things in science: the promise of proteomics. Ref Users Serv Q. 2002 Winter; 42(2):110–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lascar C, Barnett P. Defining and searching pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics to identify its core research journals. Sci Technol Lib. 2005 Sept; 26(1):69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. Where do molecular biology graduate students find information? Sci Technol Lib. 2005 Apr; 23(3):89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Owen DJ. Library instruction in genomic informatics: an introductory library class for retrieving information from molecular genetics databases. Sci Technol Lib. 1995 Mar; 15(3:):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois MP, Handel MA. A collaborative approach to teaching genetics information resources. Res Strateg. 1998 Fall; 16(3):211–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant MR, Miyamoto MM. The role of medical libraries in undergraduate education: a case study in genetics. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Apr; 90(2):181–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff F, Florance V. The informationist: a new health profession? Ann Intern Med. 2000 Jun; 132(2):996–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutchak TS. Informationists and librarians [editorial]. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4):391–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florance V, Giuse NB, and Ketchell DS. Information in context: integrating information specialists into practice settings. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan; 90(1):49–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detlefesen EG. The education of informationists, from the perspective of a library and information sciences educator. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan; 90(1):59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh W. Medical informatics education: an alternative pathway for training informationists. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan; 90(1):76–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan JM, McGowan JJ. The Medical Library Association: promoting new roles for health information professionals. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan; 90(1):80–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman JP, Cunningham DJ, Holst R, and Watson LA. The informationist conference: report. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Oct; 90(4):458–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Koonce TY, Jerome RN, Cahall M, Sathe NA, and Williams A. Evolution of a mature clinical informationist model. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005 May; 3(2):249–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpi K. Bioinformatics training by librarians and for librarians: developing the skills needed to support molecular biology and clinical genetics information instruction. Issues Sci Technol Librariansh [serial online]. 2003 Spring. [cited 13 Oct. 2005]. <http://www.istl.org/03-spring/article1.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon J, Giuse NB, Williams A, Koonce T, and Walden R. A model for training the new bioinformationist. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Apr; 92(2):188–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMullen WJ, Vaughan KTL, and Moore ME. Planning bioinformatics education and information services in an academic health sciences library. Coll Res Libr. 2004 Jul; 65(4:):320–33. [Google Scholar]

- Helms AJ, Bradford KD, Warren NJ, and Schwartz DG. Bioinformatics opportunities for health sciences librarians and information professions. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Oct; 92(4):489–930. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore ME, Shaw-Kokot J. Building a bioinformatics community of practice through library education programs. Med Ref Serv Q. 2004 Fall; 23(3):71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant MR. Bioinformatics librarian: meeting the information needs of genetics and bioinformatics researchers. Ref Serv Rev. 2005 Mar; 33(1):12–9. [Google Scholar]