Introduction

Before 1994, South Africa's public health services were racially segregated, highly unequally distributed between the rural and urban areas and rich and poor communities, overwhelmingly hospital based and curative in their emphasis. Management responsibility was also fragmented between different authorities—national, provincial, local and the former homelands. Since 1994 policies and structures have been put in place to reduce the previous fragmentation by creating an integrated national health system, based upon primary health care, and decentralized in terms of management to geographically defined districts. The private health care sector, which caters for approximately 20% of the population, yet consumes almost 60% of the resources (financial and human) devoted to health care, still remains largely unaffected by these changes in policy and organization.

The challenge of transforming the public health care sector has raised questions about the optimal approach to conceptualizing and providing comprehensive and integrated health care in the present international and national policy climate. This article interrogates some of the debates, which have marked the transformation process in South Africa. In particular it explores the tension between a comprehensive primary health care approach (CPHC) as elaborated in the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978 and more recent approaches, variously termed ‘selective primary health care’ [1] and the ‘new universalism’ [2]. An attempt to develop comprehensive care and an integrated, decentralized system is illustrated through the use of a case study, which centers on implementation of nutrition policy in South Africa's Eastern Cape Province.

Selective primary health care and the primary health care package

The concept of PHC, codified in the Alma Ata Declaration explicitly outlined a strategy, which would respond more equitably, appropriately and effectively to basic health care needs and also address the underlying social, economic and political causes of poor health. Certain principles were to underpin the PHC approach (PHCA), namely, universal accessibility and coverage on the basis of need; comprehensive care with an emphasis on disease prevention and health promotion; community and individual involvement and self-reliance; inter-sectoral action for health; and appropriate technology and cost-effectiveness in relation to available resources.

An important response to the challenge of transforming the South African health system has been a recently proposed ‘Core Package of Primary Health Care Services’ [3]. Through the identification of ‘critical’ services it is hoped that a set menu of services can be offered at each level of care—community, primary (clinic and health centers) and hospital. For instance, for malnutrition the core package consists of providing nutrition messages in the community, growth monitoring in the clinic and treatment protocols in the hospital. This approach is very attractive to health managers with its neat outline of tasks, timetables and costs for each level of care.

This approach builds upon the legacy of ‘selective primary health care’ [1], which was a response to the CPHC outlined at Alma Ata. The adoption of certain selected interventions, such as growth monitoring, oral rehydration therapy (ORT), breastfeeding and immunization (GOBI), it was argued, would be the ‘leading edge’ of PHC ushering in a more comprehensive approach at a later stage. This approach was nurtured by the prevailing conservative political ideology of the 1980s which encouraged a focus away from the broader determinants of health—such as income in-equalities, the environment, community development—towards an emphasis on health care technologies. The result was the enthusiastic promotion of selected interventions, which received generous funding to the detriment of more comprehensive approaches.

Selective PHC was given further credence by the World Bank's 1993 World Development Report, “Investing in Health” [4], which recognized the importance of health to development. Based on calculations of burden of disease globally and in different regions, it specified the most cost-effective health interventions, and culminating in the formulation of a core package of health services to be provided at the different levels of care. The identification of core packages became a mechanism to ration the cost of health services provided by the state, as other activities were to be taken up by non-government organisations. This fitted in neatly with the Bank's wider economic and fiscal policies, encouraging the privatisation of health care delivery and the cutting back of State services.

Proponents of this approach have pointed to the successes in increasing immunization rates, reducing infant mortality and the eradication of polio. However, closer examination of these achievements reveals the shortcomings of an approach, which does not integrate the different levels of care or situate health within a wider context. There is growing evidence that immunisation coverage is stagnating and even declining in many countries [5], infant mortality rates are rising in many Sub-Saharan countries [6, 7] and the health of many children is now deteriorating [8]. Evaluations have raised questions about the sustainability of mass immunisation campaigns [9], the effectiveness of health facility based growth monitoring [10] and the appropriateness of ORT when promoted as sachets or packets and without a corresponding emphasis on nutrition, water and sanitation [11]. A recent review has even pointed out the lack of evidence for the effectiveness of directly observed therapy for TB (DOTS) in the absence of a well functioning health services and community engagement [12]. Evaluations at both national and provincial levels have found that it is only when these core service activities are embedded in a more comprehensive approach (which includes paying attention to health systems and human capacity development) that real and sustainable improvements in the health status of populations are seen [13–15].

A comprehensive strategy for health development1

CPHC, however, is based on the understanding that health improvement results from a reduction in both the effects of disease (morbidity and mortality) and its incidence as well as from a general increase in social well-being. The effects of disease may be modified by successful treatment and rehabilitation and its incidence may be reduced by preventive measures. Well-being may be promoted by improved social environments created by the harnessing of popular and political will and effective intersectoral action.

Of particular relevance to the development of comprehensive health systems is the clause in the Alma Ata declaration stating that PHC “addresses the main health problems in the community, providing promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative services accordingly” [16].

Comprehensive health systems include, therefore, curative and rehabilitative components to address the effects of health problems, a preventive component to address the immediate and underlying causative factors which operate at the level of the individual, and a promotive component which addresses the more basic (intersectoral) causes which operate usually at the level of society.

Table 1 below illustrates, using some common health problems, the complementary role of the different components in holistically tackling them. Such a matrix, which starts from a disease focus, is useful for health professionals in providing them with an understanding of both the health care as well as broader, developmental interventions required to comprehensively address them.

Table 1.

Comprehensive primary health care for some common diseases: a summary framework of priority interventions [17]

| Intervention |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | Rehabilitative | Curative | Preventive | Promotive |

| Diarrhoea | Nutrition rehabilitation | Oral rehydration Nutrition support | Education for personal and food hygiene Breastfeeding Measles immunisation |

Water Sanitation Household Food Security Improved child care |

| Pneumonia | Nutrition rehabilitation | Chemotherapy | Immunisation | Nutrition Housing Clean Air |

| Measles | Nutrition rehabilitation | Chemotherapy Nutrition Support |

Immunisation | Nutrition Housing |

| Tuberculosis | Nutrition rehabilitation Social rehabilitation |

Chemotherapy Nutrition support |

Immunization Contacts (tracing) |

Nutrition Housing Ventilation |

| Cardiovascular disease | Weight loss Graded exercise Stress control |

Drug treatment Supportive therapy |

Nutrition education Increased exercise Treat hypertension Smoking cessation |

Nutrition policy Tobacco control Recreational facilities |

Strategies for comprehensively tackling such health problems can be grouped essentially under two complementary headings: promoting healthy policies and plans and implementing comprehensive and decentralised health systems. Success of these strategies depends upon the creation of a facilitatory environment through such actions as advocacy, community mobilisation, capacity-building, organisational change, financing and legislation.

Below we outline the principles of implementation of comprehensive and decentralized health systems. We first refer briefly to the strategy of health promotion whose operationalisation is usually explicitly inter-sectoral from the outset. We then focus upon the key steps in developing comprehensive, community-based programmes structured around common health problems, and on the integration of such programmes into decentralized health systems.

Implementing comprehensive and decentralised health systems

The implementation of PHC has too often focused only on the (often facility-based) curative and personal preventive components of comprehensive care, while the health promotion initiative has stressed the broader social components. This gap needs urgently to be bridged since they are clearly indivisible in the process of health development and providing integrated care.

Health promotion in practice

The implementation of healthy public policies, which emphasise the role of intersectoral activity, has been significantly enhanced since the late 1980s by the growth of the health promotion movement. The Healthy Cities initiative [18], and subsequently a focus on other settings such as schools, markets, work places and hospitals, demonstrate an approach which takes forward the policy development activities described above. These initiatives can garner political support and encourage local agencies and sectors to reassess their policies and practices in influencing health. By 1997 there were over 1000 communities participating worldwide in the Healthy Cities initiative.

Facilitating organisational change and encouraging (particularly government) staff to be more flexible, innovative and responsive to local communities are key actions in achieving success [17]. In the past many of the initiatives to promote community participation in health have concentrated on inviting community people to participate in activities established (and largely controlled) by the health services. A recent WHO study uncovered a wide range of community groups or organisations—which have been termed ‘health development structures’ (HDSs)—that play some role in promoting health. A report noted that “the majority of HDSs owe their origins to age-old community traditions of mutual support and cooperation and have a long history of community action” [19]. They include, in addition to representative health councils, women's groups, youth groups, social clubs, cooperative societies, mutual aid societies and sporting clubs. There are many roles, often invisible, played by such groups, that contribute to improving health. This could be achieved more systematically in partnership with the health sector, but has hitherto been largely unexploited. Settings-based health promotion initiatives offer a perspective and mechanism for this kind of relationship. The concept of health promoting districts holds much promise and should be developed as a means of extending health services towards a more intersectoral and developmental role.

The development of comprehensive, community-based programmes

Whereas health promotion activities, recognising the fundamental contribution to health of equitable social and economic development, commence with a multisectoral focus, programmes originating around diseases or health problems start from a health care or service response. While curative, preventive and caring actions are very important and still constitute the core of medical care, comprehensive PHC demands that they be accompanied by rehabilitative and promotive actions. By addressing priority health problems comprehensively as indicated in the table above, a set of activities common to a number of health programmes will be developed as well as a horizontalised infrastructure. The promotive activities will necessarily involve other sectors and, if successful and widespread, create pressure for supportive policy responses.

The principles of programme development apply to all health problems, whether specific communicable (e.g. diarrhoea) or non-communicable diseases (e.g. ischaemic heart disease) or health-related problems (e.g. domestic violence).

Much experience has been gained internationally in the development of comprehensive and integrated programmes to combat undernutrition: these experiences can provide useful lessons for other programmes.

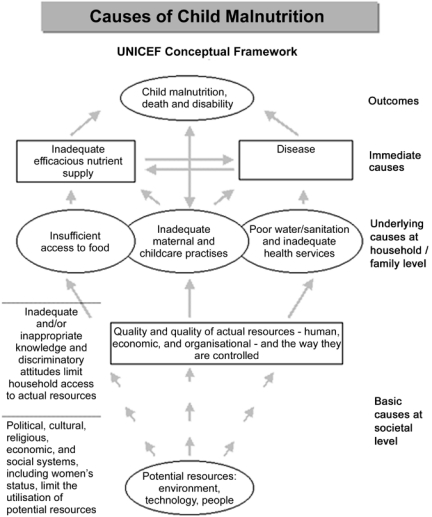

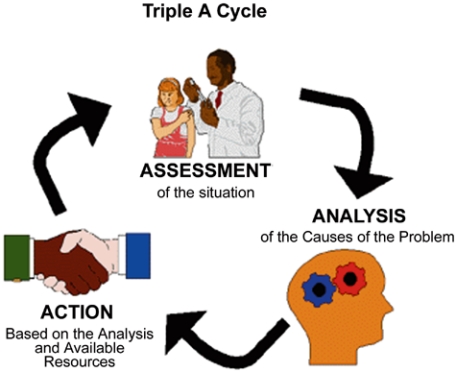

After the priority health problems in a district or local level have been identified, the first step in programme development is the conducting of a situation analysis. This should identify the prevalence and distribution of the problem, its causes, and potential resources, including community capacities and strengths, which can be mobilised and actions which can be undertaken to address the problem. The more effective programmes have taken the above approach, involving health workers, other sectors’ workers and the community in the three phases of programme development, namely, assessment of the nature and extent of the problem, analysis of its multilevel causation and action to address the linked causes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Causes of undernutrition.

This approach to implementation has thus been termed the “Triple A cycle” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Similar minimum or core service components can also be identified for other health programmes e.g. activities in the Safe Motherhood Initiative, the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness, DOTS, technical guidelines for the management of common non-communicable diseases etc. There is an advantage in standardising and replicating these core activities in health facilities at different levels, thus reinforcing their practice throughout the health system.

The development of a decentralised health system

There are at local level in most countries a number of programmes, often vertically organised and centrally administered, with specialised staff who performs only programme functions. The development of comprehensive programmes which are integrated into a decentralised district service inevitably requires transformation of both management systems and practice. Making the transition from a centralised bureaucratic system to a decentralised, client-oriented organisational culture calls for a significant investment in developing both management systems and structures and the management capacity of health personnel. District level staff must be able to support decentralised development of comprehensive programmes with clear roles, goals and procedures.

The case study which follows illustrates a number of the principles described above of the process of development of a comprehensive programme and the impact of such a programme on the creation of an integrated district health system (Photo 1).

Photo 1.

Nutrition programme and health systems development in Mount Frere

Mount Frere health district is one of the poorest districts in the country. It lies 100 km north of Umtata in the old homeland region of Transkei and is home to approximately 300,000 people. The whole area is a beautiful part of the country full of magnificent scenery. However, the terrain is also very rugged and inaccessible. There are only two tarred roads in the whole district. At times of heavy rain, or after heavy snow some roads can become totally impassable. In 1999 it was declared a national emergency area following devastation by a tornado and, more recently, by veld fires.

A recent local survey found the crude birth and death rates to be significantly higher than those for the rest of the Province. More than two thirds (71%) of households use water from unprotected sources for drinking purposes. More than two fifths of births (45%) occurred at home and were therefore not attended by health professionals. Regional surveys have found more than one in three children to be stunted in their growth and a majority of children and women probably suffer from undernutrition.

Being a health worker in Mount Frere is not easy. Years of neglect and poor resources have resulted in a health system which is barely functional. If the poor of Mount Frere are to become empowered they need a health service which delivers adequate quality services and also seeks to involve them in tackling their health and development challenges. This in turn requires public sector workers to gain the confidence and skills to optimise the quality of service they offer and to understand and reach out to the people they serve. Transforming the public sector to deliver high quality services is one of the major challenges of the new South Africa.

A local NGO—Health Systems Trust—contracted the Public Health Programme, University of the Western Cape to work with the local health services to devise a comprehensive programme to tackle malnutrition which had been prioritised by the local health management.

The aims of this project are:

To increase the capacity of provincial, regional and district health workers and the district health system to improve the quality of care and service that they provide.

To bring together a multi-sectoral team and empower them to initiate community-based nutrition programmes.

To help develop appropriate systems, structures and policies for the smooth and integrated functioning of different sectors and programmes, at the different levels (provincial, regional and district) of the public sector.

To assist in the development of an efficient district health system.

To develop processes and tools to assist in the implementation of the Integrated Nutrition Programme in other districts

Forming partnerships, teambuilding and advocacy

For innovation in the public sector to be successful, sustainable and replicable it must have the support of all role-players at all levels of the service. The management of the project is through a partnership between the Eastern Cape Department of Health, the Health Systems Trust and the Public Health Programme, University of the Western Cape.

An Eastern Cape Provincial Steering Committee oversees the project. This committee has provincial representatives from the following sectors: agriculture, education, environmental health, maternal, child and women's health, nutrition and welfare and a national representative from the nutrition directorate.

At the district level this is mirrored by the Mount Frere Nutrition Team which includes representatives from nutrition, maternal and child health, agriculture, education, local government, water affairs and environmental health. They have fostered teambuilding through a series of workshops which have aimed to come to a common understanding of the causes of malnutrition and to apply a planning cycle of assessment, analysis and action.

Performing an assessment

The district nutrition team has used the research skills acquired in the above workshops to conduct rapid assessments of key nutrition services and the nutrition situation in communities in the district. By developing observational checklists and interview guidelines they have assessed the quality of care of severely malnourished children in the paediatric ward, the performance of growth monitoring and promotion (GMP) at the local clinics, the environmental situation of selected communities, and the implementation and operation of the primary school nutrition programme at local schools.

For example, in examining the performance of GMP the team drew up an observation checklist of what they would expect to see. This starts with the nurse greeting the mother and ends with the nurse having a dialogue with the carer about the growth of the child. From the observations, it was clear that there were many things that could be improved. Few of the mothers were greeted, there was little or no feedback to the mothers and opportunities for group discussions were not taken up (Photo 2).

Photo 2.

The team also assessed the ability of nurses to interpret the growth chart and what kind of advice they give for different growth curves. To do this a series of growth charts were designed which showed normal growth, growth faltering, growth failure and catch up growth. Nurses were asked to interpret the charts and state what advice they would give the mothers based on the chart.

Finally, the possible reasons for the poor performance which was detected were explored through a series of semi-structured interviews with a selection of nurses from the clinics and hospitals. When asked about the reasons why GMP may not be done well in the clinic, most clinic workers mentioned the heavy workload and number of tasks (especially administrative). Only a minority mentioned a lack of training or supervision. Most thought the main use of GMP was to find children who were undernourished and would consequently qualify for a feeding scheme or require referral to the hospital. Some felt that it was also done in order to ‘collect statistics’ for surveillance; only a few mentioned that it was to initiate dialogue with the mother to promote growth of the child.

Planning and implementing interventions

The above assessment was followed by an analysis of the results and the implementation of nutrition-related interventions in the hospital, clinics and local communities. In the hospital practices to improve the in-patient care of severely malnourished children have been implemented. In the clinics training workshops to improve the management of diarrhoea and growth monitoring and promotion have been conducted. In some communities the team has assisted a local NGO, the Mvula Trust, to redesign water improvements and prioritise hygiene education programmes.

All of these interventions were critically informed by the situational assessment the team performed. So in the case of growth monitoring the team stressed the importance of practitioners being clear about the aims and objectives of GMP and to emphasise this in training. More specifically, the use of GMP for tailoring individual nutrition education messages, in the promotion of good growth and in the integration of services was stressed.

The team then thought about the skills and resources required to implement such a programme. This involved drawing up a detailed plan of activities associated with growth monitoring in the local settings. Local teams then planned how they would change their work patterns and clinic organisation to optimise growth monitoring activities.

To complete the triple A cycle the teams have been collecting routine data to assess the effectiveness of their interventions. In the hospitals there has been fall of nearly fifty percent in deaths from severe malnutrition. Supervisors and outside evaluators have confirmed much improved growth monitoring in many of the peripheral clinics. It is important to feed this back to the team in order to encourage them to tackle other nutrition problems as well (Photo 3).

Photo 3.

Sharing the success

As a result of the success of the Mount Frere project the team members are already being used to share their success with other districts in the region. All the hospitals in this region of the Eastern Cape are now implementing the programme for improving the hospital management of severe malnutrition. All four districts in the region have also initiated training for improving nutrition services in the clinics. The community participatory hygiene and sanitation tools developed by the team are also being adapted nationally. In all these cases, the Mount Frere team has been centrally involved in sharing their new-found skills and confidence.

Capacity development

The heart of this project has been the capacity development of public sector personnel in some of the poorest parts of the country. The success of this has been partly reflected above. Eastern Cape personnel have taken the lead in organising and presenting at local workshops and many have already presented their experiences at national meetings and conferences.

Conclusion

Given the historical legacy of wide inequalities in health and health care which persist six years after the advent of democracy, the South African Government is facing increasing public pressure to provide resources and quality services. In these circumstances the allure of currently dominant policies with their apparently cost-effective packages of care is understandable. However, the pressure for immediate responses needs to be reconciled with the necessity to develop human capacity and integrated systems, without which even the most robust and effective of technical interventions have been shown to be unsustainable. This paper has attempted to argue for and illustrate a more comprehensive approach in which tested technical interventions are located in a broader process of capacity strengthening and systems development.

The key issues raised in this article relate to interpretation and implementation of the Primary Health Care Approach. A tension which has informed international and national policies and programmes has existed, almost from the time PHC was conceived, between a more comprehensive and integrated approach and one which is more selective. The former combines technical health care with intersectoral activities, and rests upon and facilitates a long-term social process involving capacity development of both communities and technicians. The latter selects technical health care interventions, primarily on the basis of their cost-effectiveness, and often “delivers” these through vertical programmes—with their own infrastructure, administration and personnel. The latter “selective” approach, albeit in sophisticated form, is currently dominant in international health policy and appears also to be highly influential in contemporary South Africa, which is facing the enormous challenge of implementation following years of apartheid neglect. The case study described in this paper outlines the early phases of a programme to combat child undernutrition in a remote, impoverished rural district in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa.

The choice between a selective and a more comprehensive approach is one which is both immediate and stark in present-day South Africa, where new policies and activities are being engaged with on a daily basis. The authors contend, however, that the issues raised in this article have broader application and profound implications for health systems development. In the case of other complex, multicausal health problems, for example, HIV/AIDS and T.B., it is already clear that narrow, vertical approaches are having little impact on their spread. A case has been made for a more multi-faceted and integrated approach, central to which is an action learning process whose outcomes include improved understanding of the causes of particular problems and enhanced capacity to address them (Photo 4).

Photo 4.

Key questions to be answered revolve around sustainability and replicability, since it is clear that impact can and does result from such approaches—in common with more selective technical approaches. Thus, in the hospital-based component of the Mt Frere nutrition programme it has been possible to substantially reduce the case fatality rate from severe malnutrition among hospital inpatients. This has been accompanied by demonstrable improvements in knowledge and skills amongst both nurses and doctors. Moreover, some of these skills are “generic” and transferable to other aspects of hospital child care. It is, however, important to demonstrate that this improved practice is sustained without ongoing external support (from the UWC team) and that this experience is replicable within the South African public health services. Such research is not only necessary to justify past and continuing investment in the Mt Frere project, but crucial for the longer-term development of comprehensive and integrated health systems in South Africa and beyond.

Footnotes

This section draws heavily upon Sanders D, “PHC 21 – Everybody's Business”, Main background paper for an international meeting to celebrate twenty years after Alma Ata, Almaty, Kazakhstan, 27-28 November 1998, World Health Organisation WHO/EIP/OSD/00.7

Contributor Information

David Sanders, School of Public Health, University of Western Cape.

Mickey Chopra, School of Public Health, University of Western Cape.

Vitae

Professor David Sanders qualified as a medical doctor in Zimbabwe and later specialised in Britain in Paediatrics and Tropical Public Health. In 1980 he returned to newly independent Zimbabwe as Coordinator of a rural health programme developed by OXFAM in association with the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health. He later joined the University of Zimbabwe Medical School, initially as a lecturer in Paediatrics and Child Health and later became Associate Professor and Chairperson of the Department of Community Medicine. In 1993 he was appointed as Professor and Director of a new Public Health Programme at the University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa, which provides practice-oriented education and training in public health and primary health care to a wide range of health and development workers. He is the author of two books: ‘The Struggle for Health: Medicine and the Politics of Underdevelopment’ and ‘Questioning the Solution: the Politics of Primary Health Care and Child Survival’ as well as several booklets and articles on the political economy of health, structural adjustment, child nutrition and health personnel education.

Dr Mickey Chopra is a senior lecturer at the School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape. His main areas of interest are community child health and nutrition and health systems research. These interests grew out of his experiences of being a medical officer in rural South Africa where the previous lack of health systems and community programmes resulted in high levels of childhood mortality and morbidity.

References

- 1.Walsh JA, Warren KS. Selective primary health care: an interim strategy for disease control in developing countries. New England Journal of Medicine. 1979;301:967–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197911013011804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. The world health report 2000: health Systems: Improving Performance Geneva. 2000.

- 3.Daviaud E, Cabral J, Elgoni A. Developing a core package of primary health care services. South African Medical Journal. 1998;88:371. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Bank. World development report: investing in health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF State of the world's children. Oxford England: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation World Health Report 1996. Geneva: WHO Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNICEF State of the world's children. Oxford England: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadomski A, Black, Mosley WH. Constraints to the potential impact of child survival in developing countries. Health Policy and Planning. 1990;5:236–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall AJ, Cutts FT. Lessons from measles vaccination in developing countries. British Medical Journal. 1993;307:1294–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra M, Sanders D. Is growth monitoring worthwhile in South Africa? South African Medical Journal. 1997;87:875–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werner D, Sanders D. Questioning the solution: the politics of primary health care and child survival. Palo Alto USA: Healthwrights; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volmink J, Garner P. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of strategies to promote adherence to tuberculosis treatment. British Medical Journal. 1997 Nov 29;315(7120):1403–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halstead SB, Walsh JA, Warren K, editors. Good health at low cost. New York: Rockefeller Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzroy H, Briend A, Fauveau V. Child survival: should the strategy be redesigned? experience from Bangladesh. Health Policy and Planning. 1990;5:226–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez G, Tapia-Conyer R, Guiscafre H, Reyes H, Martinez H, Kumate J. Impact of oral rehydration and selected public health interventions on reduction of mortality from childhood diarrhoeal diseases in Mexico. Bull WHO. 1996;74:189–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organisation and UNICEF Report of the International Conference on primary health care. Alma Ata: USSR; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders D. “PHC 21—Everybody's Business”, Main background paper for an international meeting to celebrate twenty years after Alma Ata, Almaty, Kazakhstan, 27–28 November 1998, World Health Organisation WHO/EIP/OSD/00.7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baum F. The new public health: an Australian perspective. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organisation (WHO) Health development structures in district health systems: the hidden resources. Geneva: World Health Organisation Division of Strengthening Health Services. 1994. Available from: URL: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1994/WHO_SHS_DHS_94.9.pdf.