SYNOPSIS

Objectives

The purpose of this research was to: (1) examine judgments about immigrants who are victims of and assailants in intimate partner violence, and (2) assess whether immigrants to the U.S., a diverse and growing population, know that intimate partner violence is illegal in the United States and their judgments about what sanctions, if any, should follow.

Methods

A random-digit-dial telephone survey was conducted in four languages with 3,679 California adults. There were roughly comparable numbers of white, black, Latino, Korean American, Vietnamese American, and other Asian American participants; 60.1% were born outside the U.S. An experimental vignette design was used to vary victim, assailant, and contextual factors about incidents of intimate partner violence and to assess respondents’ judgments about the behavior and what should be done about it. Multivariate analyses were conducted to examine the independent effect of these predictor variables and characteristics of the respondents.

Results

Respondent judgments about whether an incident of intimate partner violence was wrong, illegal, or about what sanctions should follow were not related to nativity of either the victim or the assailant. Immigrant respondents differed from native-born respondents on two outcomes: immigrants were more likely to think that the behavior was illegal and that guns should be removed from the assailant.

Conclusions

Concerns that immigrants do not know that intimate partner violence is illegal in the U.S. are largely misplaced—immigrants know it soon after their arrival in the U.S. In addition, it appears that a cultural defense regarding domestic violence is not likely to sway others.

The United States has been described as a land of immigrants, an observation that applies not just to the nation’s past. Currently, one of every nine people in the U.S. was born outside the country,1 and one in ten have a parent who is an immigrant.2 Many immigrants are new: over half of the immigrants to the U.S. have arrived since 1990.1

Immigrants are concentrated in the West and in urban areas, but settlements sometimes appear in unexpected areas of the country. Three locales illustrate this point well: (1) in Durham County, North Carolina, public school children hearken from 60 different countries;3 (2) although not as populous as many Vietnamese American communities, an area stretching from Seadrift, Texas, past Biloxi, Mississippi, includes several towns with the highest concentrations of Vietnamese immigrants in the nation;4 and (3) in rural Storm Lake, Iowa, Latino schoolchildren (mostly the offspring of Mexican immigrants working in meat packing plants) outnumber non-Hispanic white schoolchildren.5 Thus, public health efforts related to immigrants need to be widely dispersed across the U.S.

Immigrants bring a vital history and a set of cultural norms and personal beliefs that may differ in important ways from current U.S. society. Perceptions about and legal sanctions against intimate partner violence (IPV) vary substantially around the world.6 For example, beating one’s wife was deemed illegal for the first time in Japan in October 2001. Thus, it is not surprising that immigrants from both developed and undeveloped countries sometimes are described as being uninformed about U.S. laws and norms regarding intimate partner violence. To my knowledge, that assumption is untested. We do not know how immigrants to the U.S. perceive IPV—Is it wrong? Is it illegal? And what sanctions, if any, should follow?

A “cultural defense” has been offered for immigrants’ behavior ranging from forced sex in “marriage by capture” to homicide following disclosure of infidelity by a spouse.7 This means that if members of the general public (both native and foreign-born) believe that certain behaviors that are considered illegal in the U.S. may be tolerated or permitted elsewhere in the world, they may be more lenient in their judgments when immigrants engage in such behaviors. These judgments may be most apparent in jury verdicts. As far as I have been able to determine, whether the behavior of immigrants (and most notably, recent immigrants) is viewed differently than that of native-born individuals in the context of intimate partner violence also remains untested.

In the present investigation, I address two questions: (1) How do immigrants judge intimate partner violence and what ought to happen following such incidents? and (2) Is the behavior of immigrants viewed differently than the behavior of U.S.-born individuals in situations of intimate partner violence? Consideration of these social judgments is important in efforts to increase the health of the population (e.g., funding allocations, community awareness campaigns, and education efforts with law enforcement officers, judges, and other members of the criminal justice community).

METHODS

Sample

Data were gathered in California, where more than one in four people is foreign-born.8 Interviews were conducted with 3,679 adults; 604 of whom were white, 550 black, 666 Latino, 619 Korean American, 623 Vietnamese American, and 617 other Asian American. The latter four groups were chosen because they contain high proportions of immigrants, whose views are of interest from scientific and practice perspectives. To include groups with high proportions of relatively recent immigrants so that we could study their social norms before they adapted to the dominant U.S. culture, we chose to oversample Korean Americans and Vietnamese Americans, the third and fourth largest Asian ethnic groups in the U.S.9 Chinese and Filipinos, the two largest Asian groups in the nation and in California, were not oversampled because Chinese consists of one written and multiple spoken languages, which created data collection difficulties in a telephone interview, and because both groups are mostly proficient in the English language. For example, when Tagalog is the primary language in the home, 92.5% report that they speak English either well or very well.10 The study sample was based on five samples: a cross-sectional sample of the state of California and four samples drawn from geographic regions known to have high proportions of the population groups of interest.

The sample was diverse in multiple ways. Of particular interest in the present investigation is that 60.1% of the overall sample were immigrants, and the proportion of immigrants in each population sample was generally consistent with population patterns: 10.3% of whites, 5.3% of blacks, 68.9% of Latinos, 96.5% of Korean Americans, 95.5% of Vietnamese Americans, and 75.9% of other Asian Americans in the sample were immigrants. The average number of years the immigrants had been in the U.S. was 14.3, which compares favorably to the U.S. average of 14.4 years.2 The sampled immigrants were expected to reflect the diversity of the immigrant population, including legal immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, students, undocumented migrant workers, and naturalized citizens. The response rate was 51.5%, which exceeds that of other recent multi-language telephone surveys in California.11,12 In addition, a comparison of the cross-sectional sample’s key demographic characteristics to those of the general population of California adults indicated that the sample was of generally high quality. Data collection, conducted by the National Opinion Research Center, began April 11, 2000, and ended March 25, 2001.

Data collection instrument

The data collection instrument was developed with the assistance of a diverse panel of community experts—the directors of battered women’s shelters and rape crisis centers who serve diverse and multi-lingual populations, victims of intimate partner violence, and men who provide batterers’ treatment services and who developed a media campaign to prevent rape. The community experts helped ensure the cultural competence of the research (e.g., by suggesting names for use in the vignettes) as well as lent their considerable knowledge about intimate partner violence incidents (e.g., “grabbed an available object in a threatening manner” was included in the vignettes because they suggested that it is a more common behavior than the use of other external weapons in IPV).

Consistent with current survey research practices, the data collection instrument was developed following cognitive interviews and focus groups. The instrument was developed in English, translated into each of the other languages, and independently translated back into English. Minor adjustments were made to ensure equivalency of the forms, and interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, Korean, and Vietnamese.

A series of experimental vignettes (scenarios) were used to assess perceptions about IPV. The factorial vignette, a long-standing social science methodology, both minimizes the effect of social desirability bias and allows the researcher to examine the influence of each factor independent of the others.13 The primary strength of the design is the random assignment of each category for each vignette variable. The random assignment allows researchers to assess which components are important in individuals’ judgments about a topic and to examine both the main effects and interactions of two or more independent factors, as I will do here.

The questionnaire contained seven vignettes, with up to thirteen questions following each vignette. Each level (or category) of each variable was randomly assigned in each vignette, a process that created varying contexts for each type of behavior described. The variables consisted of age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, relationship status, alcohol use, incident frequency, weapon presence, whether children were involved, motivation, and type of abuse (nine forms of psychological, sexual, and physical abuse were included). Of particular interest in the present investigation is the vignette variable for both the victim and the assailant related to nativity and length of U.S. residence; the variable categories were: born in the U.S., a recent immigrant, and born outside the U.S. but has been here a long time.

After each vignette, respondents were asked a series of questions; I focus here on those that were designed to assess: (1) what behavior is tolerated under what circumstances, and (2) willingness to involve formal social agents (e.g., law enforcement). In the first vignette, all vignette variables were used and all follow-up questions were asked. To reduce respondent burden, fewer variables were used in subsequent vignettes (i.e., a fractional factorial design13 was used), and fewer follow-up questions were asked. A typical vignette might be as follows:

Amy, an Asian American woman who was born in the U.S., is living with Fernando, a Latino man who was born outside the U.S. but has been here a long time. One evening he told her that he did not want her to visit her family that night and that he would not allow it. Then he slapped her.

Standard demographic data about the respondents were collected, including information about country of birth and, if an immigrant, years in the U.S. The latter variable, nativity and length of residence, is the key variable examined herein for the respondents as well as for the victims and assailants described in the scenarios.

Statistical analysis

The vignette is the unit of analysis, resulting in a potential N of 25,753. Initial analyses consisted of frequencies, cross-tabulations and chi-square tests. Diagnostic statistics were run to assess collinearity and multicollinearity, and all were found to be acceptable. To take into account the fact that each respondent answered more than one vignette, corrected standard error terms were calculated using the robust cluster option in Stata.14 To reduce the chance of a Type I error, a Bonferroni correction for multiple statistical tests was used to adjust the level of statistical significance.

RESULTS

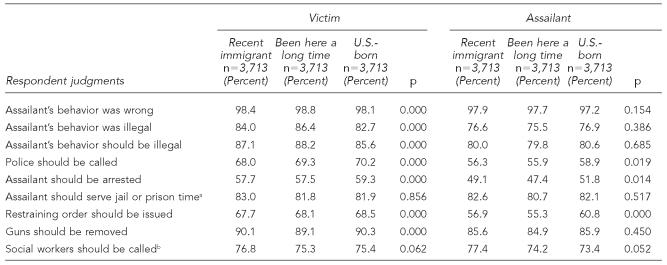

Respondent judgments about intimate partner violence (i.e., the behavior and the sanctions to follow) were very similar when the victim was a recent immigrant, an immigrant who has been in the U.S. a long time, or U.S.-born (see Table 1). Likewise, respondent judgments were largely unaffected by the nativity of assailants. Although the differences were statistically significant for several judgments, the absolute differences were so small as not to be of substantive importance.

Table 1.

Respondent judgments about intimate partner violence scenarios, by victim and assailant nativity and length of residence (percent affirmative)

NOTE: Of the 25,753 possible vignettes, 11,139 included information about the victim and assailant nativity and length of residence. The nested nature of the data are not taken into account in the chi-square analyses reported above.

The “jail/prison time” question was asked only of respondents who answered “yes” to the “should be arrested” question (n=3,336).

The “social worker” question was asked only if the vignette indicated that there was a “child in the other room during the incident” (n=3,828).

Differences are more apparent when examining the nativity and length of residence of the individuals making the judgments. As shown in Table 2, recent immigrants, long-time immigrants, and U.S.-born individuals differed in their judgments regarding many of the measured outcome variables. Whether these differences remained after other characteristics of the vignettes and the respondents were taken into account were examined next. First, however, it may be of interest to note that years in the U.S. were largely unrelated to whether immigrants thought that the behavior was illegal (see Figure).

Table 2.

Respondent judgments about intimate partner violence scenarios, by respondent nativity and length of residence (percent affirmative)

In the U.S. five or fewer years

In the U.S. more than five years

The “jail/prison time” question was asked only when respondents answered “yes” to the “should be arrested” question (n=8,434).

The “social worker” question was asked only if the vignette indicated that there was a “child in the other room during the incident” (n=7,188).

Multivariate analyses that took into account all manipulated vignette characteristics and all measured respondent characteristics were largely consistent with the observations above. Multiple logistic regressions (see Table 3) indicated that victim and assailant nativity and length of residence do not predict respondent judgments about the behavior and what sanctions should follow. In addition, as shown in Table 3, the variable combining respondent nativity and length of residence also is of limited relevance when predicting each outcome. Only two variables differed by respondent nativity and length of residence: immigrants have higher odds than non-immigrants of believing that the behaviors described in the scenario were illegal (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]51.74 for recent immigrants and 1.81 for long-term immigrants), and immigrants have higher odds of believing that firearms should be removed after an incident (AOR52.54 for recent immigrants and 2.09 for long-term immigrants). Although the finding did not meet the adjusted level of statistical significance, it may be of substantive interest to note that immigrants also have higher odds of believing that social workers should be called to check on the children in incidents of intimate partner violence.

Table 3.

Vignette and respondent predictors of beliefs about intimate partner violence scenarios, multivariate logistic regression findings

NOTE: All vignette variables and all measured respondent variables, as well as the clustered nature of the observations, were taken into consideration in these analyses. Other vignette and respondent variables that were taken into account are: vignette variables—victim and assailant age, victim ethnicity, assailant ethnicity, victim gender, assailant gender, victim socioeconomic status, assailant socioeconomic status, weapon availability, motivation, type of abuse, whether children were near, victim alcohol use, assailant alcohol use, and frequency of incident; respondent variables—age, ethnicity, relationship status, ever married, ever divorced, children younger than 5 years old, children aged 5–17 years, number of adults in household, education level, employment status, income, number of individuals supported on income, urbanicity, and personal knowledge of a victim of intimate partner violence.

p<0.00047, the statistical significance level after making a Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

The final set of multivariate analyses assessed whether, after taking into consideration all other vignette and respondent characteristics, there is an interaction between respondent nativity and victim and assailant nativity. There was no evidence (data not tabled) that the judgments of recent immigrants, long-time residents, and U.S.-born individuals differed based on whether the victim or assailant was a recent immigrant, long-time resident, or U.S.-born.

DISCUSSION

Public health resources are scarce and must be spent wisely. Findings reported here suggest that increased educational efforts about intimate partner violence being illegal in the U.S. are not indicated for immigrants. Length of time in the U.S. is largely unrelated to whether immigrants believe specific behaviors are considered illegal, suggesting that: (1) the social norms immigrants bring from their home countries may not be all that different from those operating in the U.S.; (2) immigrants learn quickly about U.S. norms and laws about IPV; or (3) efforts to educate immigrants about topics such as these are successful. If anything, immigrants appear to be more likely than U.S.-born individuals to believe that a variety of abusive behaviors toward one’s intimate partner is considered illegal. Such knowledge and perceptions may be useful, but as shown in the U.S. (where legal restrictions on wife beating have been in place for more than a century), making a behavior illegal does not eliminate or perhaps even reduce it.

In terms of how to intervene following incidents of intimate partner violence, immigrants appear to differ little from U.S.-born individuals, with one exception: immigrants are more likely to believe that firearms should be removed after an incident. This finding may reflect U.S. norms about firearm ownership and possession: guns are more likely to be available to civilians in the U.S. than to civilians in many of the countries of origin of immigrants to the U.S., and immigrants appear to maintain these values about guns. Other differences between immigrants and the native-born may be identified in subsequent research; for example, analyses of other portions of these data indicate that individuals born outside of the U.S. (vs. native-born) are more inclined to attribute fault to the victim and less inclined to think the victim should take self-protective action.15 However, the present investigation documents that the two populations do not differ in their overall judgments about intimate partner violence and what should be done about it at a societal level.

In addition, study findings suggest that individuals accused of IPV are likely to be judged similarly in the U.S., at least on the basis of their nativity and length of time in the country. The same holds for victims of IPV. Thus, while a “cultural defense” may be effective for some individuals in certain legal or other situations, it does not appear that either the U.S.-born or foreign-born, as a group, are likely to offer broad support to such considerations.

Additional considerations

Immigrants, as a group, are likely to be at higher risk of intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration for reasons unrelated to their experience as immigrants. Most notable is the observation that the immigrant population contains higher proportions of men and young people. With higher proportions of men (the primary perpetrators of injury-producing IPV) and younger people (who are at high risk of fatal and nonfatal IPV),16 immigrants are at increased risk by virtue of these two demographic characteristics alone.

Marriage patterns are also important when considering intimate partner violence in the U.S. Nearly one in six married couple families in the U.S. include a foreign-born spouse,2 and about one-third of these marriages include a U.S.-born spouse. Including Asian American groups when studying social norms about IPV is particularly important given that Asian American women are more likely than others to marry outside their ethnic group.17 Thus, potential cultural differences about the use of physical, sexual, and verbal behaviors in intimate relationships need to be resolved at interpersonal as well as societal levels.

Given fertility patterns, if rates of marital violence are the same in immigrant and U.S.-born populations, nearly 50% more children living with immigrants will witness intimate partner violence in their homes. In 2000, nearly one in six U.S. children lived with a foreign-born householder.2 Immigrant families have a higher average number of children under the age 18 than native-born families (0.99 vs. 0.65). The risk is higher among the children of immigrants from Mexico, who comprise nearly half of the immigrants to the U.S.,2 because their fertility rate is the highest among immigrants.

In addition, nativity and ethnicity are closely linked in the U.S. The proportion of foreign-born individuals is highest among Asian Americans and Hispanics (61.4% and 39.1%, respectively) and lowest among blacks and whites (6.3% and 3.5%, respectively).2 Thus, research on intimate partner violence, or any public health topic for that matter, should examine and take into consideration, as was done here, both nativity and ethnicity to avoid attributing the effects of one to the other.

One more demographic characteristic to consider is length of time in the country. If other research identifies length of residence as a key consideration in the occurrence of intimate partner violence in foreign-born populations, it is important to recall that over half of the immigrants to the U.S. have arrived since 1990. Recent immigrants are likely to be young; moreover, each decade, the bulk of immigrants to the U.S. is about five years younger.18 Among immigrants arriving in or since 2000, 58.2% are between the ages of 15 and 3418 compared to 35.9% of the overall immigrant population18 and 26.6% of the native-born population.1 This age group is at high risk of intimate partner violence. Thus, immigrants’ age-related risk for intimate partner violence is likely to continue into the foreseeable future.

In addition, more research on immigrants and intimate partner violence is needed. Population-based surveys of community residents, in particular, are in short supply. Intervention and research efforts should include persons with immigrant parents; this population, straddling two cultures, may be at particular risk for IPV.19 Understanding social norm changes across generations is important because the family is the primary social institution by which social norms, the written and unwritten rules of society, are transmitted.

CONCLUSIONS

In sum, efforts to reduce intimate partner violence in the U.S. would be wise to take immigrant populations into account. By their population structure alone, immigrants are at elevated risk of IPV victimization and perpetration. Immigrants, as a group, however, appear not to differ substantially from native-born individuals in their perceptions of IPV and what sanctions should follow. Some tailoring of prevention programs and other interventions will undoubtedly be needed for specific groups, including specific immigrant groups, regarding specific topics. If these findings are borne out in subsequent research, broad population-based efforts to reduce intimate partner violence (vs. immigrant-directed campaigns about it being illegal) are indicated. Successful prevention efforts that include immigrant and native populations are likely to be wise investments.

Figure.

Proportion of immigrants reporting that the behaviors described in the vignettes are illegal

NOTE: Regardless of ethnicity and years in the U.S., 81.4% of immigrants (vs. 70.2% of U.S.-born individuals) reported that the behaviors were illegal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Larsen LJ. Foreign-born population in the United States: 2003. Current Population Reports, P20-551. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2004. [cited 2005 Feb 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/foreign/cps2003.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Census Bureau (US) Profile of the foreign-born population in the United States. 2000. [cited 2004 Mar 23]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/p23-206.pdf.

- 3.Durham Public Schools: leaders in the state. [cited 2005 Apr 5]. Available from: URL: http://www.durham-nc.com/stats/news_story_ideas/stories/dps_accolades.php.

- 4.Kang KC, Fields R. Los Angeles Times. 2001 May 15; Asian population in U.S. surges, but unevenly. Sect. A:16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latinos outnumber Anglos in SL schools. [cited 2005 Apr 4];Storm Lake Times. 2005 Apr 2;:1. Available from: URL: http://www.stormlake.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domestic violence laws of the world. [cited 2005 Apr 12]. Available from: URL: http://annualreview.law.harvard.edu/population/domesticviolence/domesticviolence.htm.

- 7.Gallin AJ. The cultural defense: undermining the policies against domestic violence. Boston College Law Rev. 1994;35:723–45. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Census Bureau (US) State and county quickfacts: California. 2000. [cited 2003 Mar 14]. Available from: URL: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06000.html.

- 9.Census Bureau (US) [cited 2002 Mar 29];The Asian population: 2000. Census 2000 brief. Table 4. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin HB, Bruno R. [cited 2006 Mar 27];Language use and English-speaking ability. Census 2000 brief. Table 1. Available from: URL: www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-29.pd. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Health Policy Research (University of California Los Angeles) [cited 2003 Aug 20];California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2001 methodology series: report 4—response rates. Available from: URL: http://www.chis.ucla.edu/pdf/CHIS2001_method4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinbaum Z, Stratton TL, Chavez G, Motylewski-Link C, Barrera N, Courtney JG. Female victims of intimate partner physical domestic violence (IPP-DV), California 1998. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossi PH, Anderson AB. The factorial survey design: an introduction. In: Rossi PH, Nock SL, editors. Measuring social judgments: the factorial survey approach. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stata, Inc. Stata/SE 8.1 for Macintosh. College Station (TX): Stata Corp; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor CA, Sorenson SB. Community-based norms about intimate partner violence: putting attributions of fault and responsibility into context. Sex Roles. 2005;53:573–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rennison CM. Intimate partner violence and age of victim, 1993-1999. [cited 2005 Apr 12]. Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 187635, October 2001, revised November 2001. Available from: URL: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/abstract/ipva99.htm.

- 17.Census Bureau (US) Hispanic origin and race of coupled households (PCH-T-19). Table 1. Hispanic origin and race of wife and husband in married-couple households for the United States. 2000. [cited 2005 Apr 12]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/phc-t19.html.

- 18.Census Bureau (US) Foregin-born population of the United States, current population survey—March 2003, detailed tables (PPL-174) [cited 2005 Feb 11];Table 2.1 Foreign-born population by sex, age, and year of entry. 2003 Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/foreign/ppl-174.html#yoe. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorenson SB, Telles CA. Self-reports of spousal violence in a Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white population. Violence Vict. 1991;6:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]