SYNOPSIS

Objectives

This study examined whether the odds of subsequent domestic violence by married men are reduced when women file for divorce, and whether these odds are further influenced by the timing of divorce proceedings.

Methods

The sample included 703 married men arrested for misdemeanor assaults on spouses in Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Ohio. Logistic regression models were estimated to determine whether men with divorces filed against them (after entry into the study) were less likely to be re-arrested during a fixed 24-month follow-up period. A survival analysis of differences in time to re-arrest for men with filed divorces versus those without was also conducted, as well as an analysis of the speed of divorce filings and re-arrest.

Results

Only 24% of all offenders had divorce papers filed in court during the study period. Divorce filings coincided with (1) lower likelihoods of re-arrest for intimate assault, (2) lower likelihoods of re-arrest during each month of -follow-up, and (3) longer delays to re-arrest (for those who ultimately re-offended). Shorter delays to divorce filings (after initial arrest) were more effective for reducing likelihoods of subsequent assault, particularly within the first 11 months after entry into the study.

Conclusions

Findings have implications for victim support services offered through domestic violence courts. Evidence from this and future studies may provide additional incentives for support personnel to identify and overcome the barriers preventing many women from successfully filing for divorce. However, the study should be seen as offering preliminary findings on a potentially important issue.

Women who are subjected to physical abuse by their partners often face great difficulties when trying to leave abusive relationships.1–3 Some of these difficulties include retaliation or the threat of retaliation by partners/spouses, lack of social support, concern for a child's safety (when children are present), financial dependence, and a perception that the police and courts are unwilling and/or unable to offer effective protection against subsequent harm.

The last obstacle noted above is in the process of being addressed across the country through the expansion of domestic violence courts that coordinate the activities of criminal justice and social services agencies (thereby addressing both the accountability of offenders and the needs of victims).4 Dugan and her colleagues, however, caution that more evidence is needed regarding domestic violence services that are truly effective versus those that could subject women to even more harm by their partners.2,3 For example, there is evidence that some women who leave their husbands or boyfriends actually face a higher risk of subsequent assault,1–3 contributing to disagreement over the utility of separation as an effective means to reducing domestic violence. Available information on this subject remains limited, however, especially with regard to the (non)utility of pursuing divorce for married women. In this context, we examined whether filing for divorce and the timing of divorce proceedings played significant roles in altering the odds of re-arrest for intimate assault among a sample of married male offenders in Cincinnati, Ohio. We also offer a description of the prevalence and timing of divorce filings and registrations for the sample, due to the limited information currently available on this subject.

Considering the possible effects of filing for divorce on the safety of survivors

The idea that battered women should be encouraged to separate from their partners in order to avoid further abuse has waned in popularity since the beginning of the shelter movement, in part due to the evidence noted above regarding placing survivors at greater risk for subsequent harm.1–3,5,6 Scholars have posed different possible explanations for this evidence, including jealousy, retaliation, and/or threat to a male's sense of power and control.1–3,7,8 Regardless, disagreement on this issue remains. For example, Catlett and Artis argue that, for married women, divorce is a “reasonable, if not prudent, individual choice to avoid abuse.”9 Helling found that some prosecutors clearly advocate this perspective when they agree to reduce criminal charges against defendants who cooperate in divorce proceedings.10

Underlying the perspective that filing for divorce will reduce the risk of subsequent harm is the logic that offenders who are married and living with their partner may have greater opportunities to engage in domestic violence because of physical proximity. From an academic perspective, this logic is consistent with ideas drawn from low self control theory, in that desistance from crime can be explained by reduced opportunities (physical proximity) for individuals with low self control (domestic violence offenders).11 For these types of offenders, marriage may be a catalyst that promotes future violence.

In a separate analysis of repeat offending by domestic violence offenders, we found that re-arrests were less likely for unmarried individuals not living with their partners at the time of the original arrest.12 Our finding underscores the possibility that filing for divorce may help to reduce opportunities for subsequent harm. However, a limitation of our first analysis is that we measured marital status and living arrangements at the time of initial arrest only, which begs the question of whether changes in marital status (after the initial arrest) also influence likelihoods of subsequent intimate assaults. To understand the link between changing opportunities for intimate assault and likelihood of subsequent violence, we examined the effects of filing for divorce and the timing of divorce proceedings on preventing re-arrest for intimate assault among a sample of married male offenders residing in Cincinnati, Ohio.

METHODS

Following are the specific research questions addressed in our study:

What is the rate of divorce filings involving married men arrested for intimate assault?

Were the odds of re-arrest for intimate assault significantly lower among married men with divorces filed (after the initial arrest) versus married men without filed divorces?

Were there significant differences in the amount of time to re-arrest for men with filed divorces versus men without filed divorces?

Among offenders with divorces filed in court, how did the length of time between the initial arrest and filing for divorce influence the odds of re-arrest for intimate assault?

The sample for the analysis represented a sub-group of individuals arrested for misdemeanor assaults on intimates from a larger study funded by the National Institute of Justice.13 Individuals selected for the analysis described here included all married males arrested for assaulting an intimate partner in Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Ohio from November 1, 1995, to May 31, 1996 (N5743 unique individuals). Of this pool, 40 left the jurisdiction before completion of the study and so were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 703 individuals were tracked for re-arrest until May 31, 1998.

Information on offenders and their re-arrests was compiled from arrest reports, intake interview forms, and court records. Data on filed and registered divorces in Hamilton County were obtained from a website offered by the Hamilton County Courthouse.14 We must acknowledge the limitation of using official data on re-arrests as indicators of “re-assault,” given that arrest data do not capture incidents of intimate partner violence (IPV) that go undetected by police. As discussed by Bachman and Saltzman, women may not report these incidents out of concern for privacy, fear of stigmatization, and lack of confidence in the utility of official involvement.5 Women may also be reluctant to involve the police due to a fear of retaliation by their partners. Campbell offers an excellent discussion of the complexity involved in adequately assessing an offender's risk of re-assault.15 In defense of using arrest data as indicators of re-assault, Sherman and his colleagues found that official measures yielded the same conclusions as victim interviews in five of the original seven domestic violence arrest experiments (five of the six study sites) regarding the deterrent effects of arrest.16 Berk and Newton also found that examination of police data yielded conclusions similar to those derived from analyses of victim reports.17

Two different aspects of re-arrest were examined: (1) whether an offender was re-arrested for intimate assault during a fixed 24-month follow-up period beginning after court release (including any served sentences), and (2) the number of months that elapsed between the time of court release and re-arrest for intimate assault during a varied follow-up period spanning 24 to 30 months. Although the sample included individuals initially arrested for misdemeanor assaults, both felony and misdemeanor assaults were counted in the measures of re-arrest. We examined the prevalence of re-arrest (whether an offender was re-arrested or not) using logistic regression. Time to re-arrest was examined with Cox regression to adjust for the right-censored data (due to the varied follow-up period). This segment of the analysis is described with life tables displaying the cumulative proportions of suspects “surviving” re-arrest for each month during follow-up for men with filed divorces versus those without filed divorces.

We added several control measures to the analyses of the prevalence and time to re-arrest to reduce the chance of finding spurious relationships between the variables of interest. These statistical controls included a suspect's age, education, employment status and type of job, prior record of convictions, whether old charges were pending at arrest, and whether any charges were formally filed after the initial arrest. Each of these measures maintains a significant zero-order correlation with re-arrest.12

RESULTS

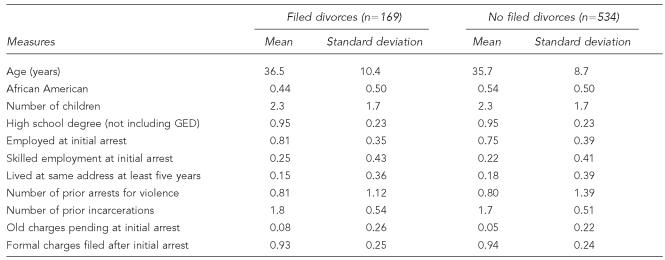

Table 1 provides a description of various demographic and socio-demographic characteristics for the sample of married men arrested for intimate assault in Hamilton County from November 1, 1995, to May 31, 1996. These descriptions are broken down separately for men with divorces filed during the study period versus men without filed divorces. A comparison of the two sub-groups reveals more similarities than differences in the distributions of characteristics, although filings might have been more common among men with higher socio-economic status (e.g., whites versus African Americans, and employed versus unemployed).

Table 1.

Description of the sample broken down by whether or not divorces were filed during the study period

NOTE: All measures are dichotomous (0 = without characteristic, 1 = with characteristic) except age, number of children, number of prior arrests for violence, and number of prior incarcerations.

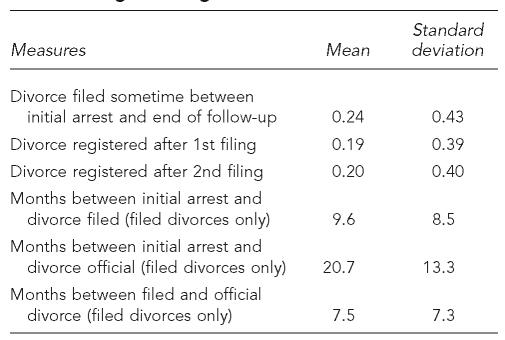

A description of the prevalence and timing of divorce filings and registrations for the sample is offered in Table 2. The measure of “months between initial arrest and divorce filed” is relevant for examining whether the likelihood of re-arrest varies by time to filing. An additional 1% of the sample already had divorces filed at the time of initial arrest. The proportion of divorces filed during the study period was 0.24, which does not appear as high as one might expect. Moreover, 20% of the original filings did not become official after the first filing because of “no-shows” in family court. These cases were still included in the multivariate analysis due to our interest in whether divorces were filed in court, and because men with pending divorces may still face fewer opportunities for intimate violence compared to men without filed divorces. Moreover, all but 5% of the original filings were subsequently registered within 60 months of the first filing.

Table 2.

Prevalence and timing of divorce filings and registrations

NOTE: Divorce measures are dichotomous (0 = without characteristic, 1 = with characteristic).

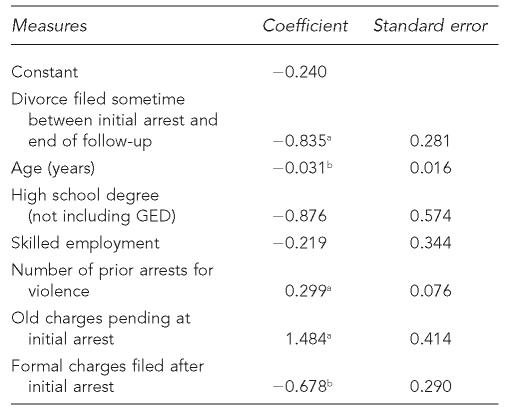

Findings for the analysis of whether divorce filings coincided with significantly lower odds of re-arrest for intimate assault during the fixed follow-up period are displayed in Table 3. These results indicate that men with filed divorces were significantly less likely to be re-arrested compared to married men with no filed divorces (p,0.01), even when controlling for other demographic and legal correlates of re-arrest. The fairly powerful effect suggests that, regardless of how much time elapsed between the initial arrest and filing, the act of filing for divorce in itself may offer significant reductions in likelihoods of subsequent abuse.

Table 3.

Logistic regression model predicting re-arrest during a fixed 24-month follow-up period (N=703)

NOTE: Model Chi-square 5 43.7; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.144

p≤0.01

p≤0.05

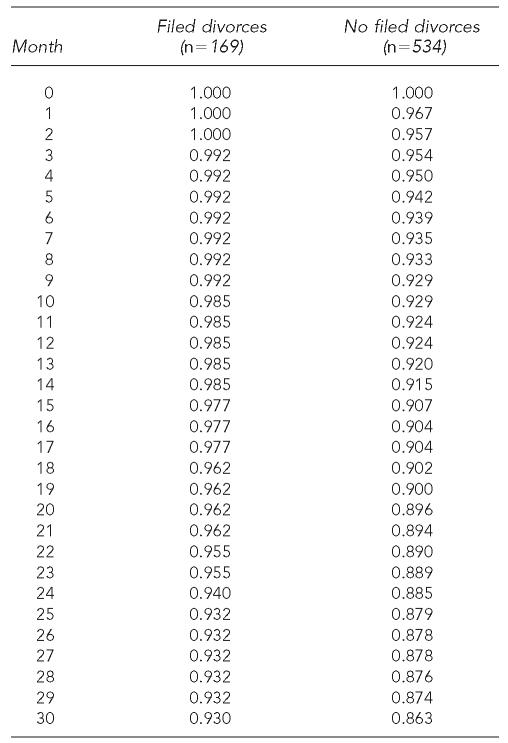

To address the third research question regarding time to re-arrest, Table 4 displays the monthly “survival” rates (i.e., no re-arrest for each specific month during follow-up) for two separate groups: offenders with no divorces filed in court versus offenders with filed divorces. Whereas findings related to the second research question revealed that filing for divorce is significantly related to the prevalence of re-arrest for intimate assault, Table 4 reveals that filing for divorce is also related to the amount of time to re-arrest. Without exception, males with filed divorces are more likely to desist from subsequent assaults on intimates during each month following initial arrest. Moreover, the monthly cumulative survival rates are significantly different between the two groups for every month examined (p,0.05, based on a comparison of confidence intervals for each pair of survival rates). The first re-arrest for males without filed divorces occurred within the first month of follow-up, versus the third month for males with filed divorces. Also note that the first group does not even drop to the rate of 0.967 for the second group (during the first month) until month 18 of the follow-up. The cumulative rate for males with filed divorces by the end of month 30 (0.93) is matched by month 9 among males with no filed divorces.

Table 4.

Cumulative proportions of males “surviving” without re-arrest during each month of the varied follow-up period (24 to 30 months), broken dow by whether or not divorces were filedn

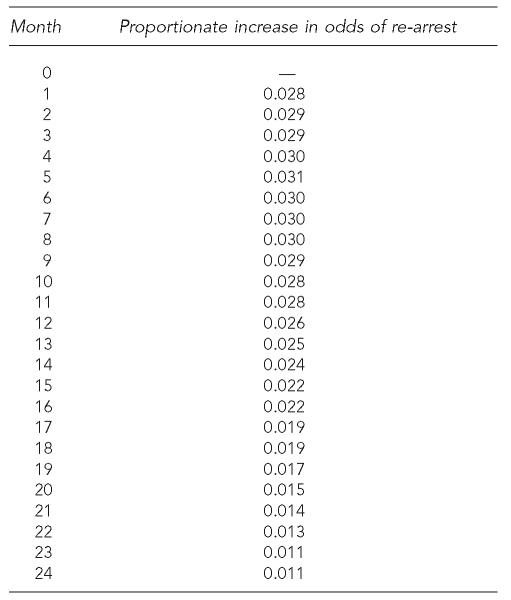

Regarding the last research question, the analysis of the relationship between re-arrest and the time to filing divorce (for males with filed divorces only) produced a statistically significant relationship at p,0.001. Findings revealed “months to filing” to be the strongest predictor relative to any of the other control variables mentioned earlier. Table 5 provides more substantive insight into this relationship through a description of the actual increase in re-arrest likelihoods during each month that divorce was delayed during follow-up.

Table 5.

Proportionate increase in the odds of re-arrest for each additional month between initial arrest and filing for divorce (filed divorces only, n=169)

The largest monthly increases in the odds of re-arrest occurred during the first 11 months of the 24-month follow-up period. That is, for each additional month that a divorce filing was delayed, the odds of re-arrest increased by roughly 3% per month (anywhere from 2.8% to 3.1%). These figures dropped steadily from 2.6% to 1.1% from 12 to 24 months. Therefore, the greatest effects of filing for divorce on desistance from subsequent violence occurred with earlier filings.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with the idea that reducing opportunities for violence plays a significant role in desistance from intimate assault, divorce filings coincided with (1) lower likelihoods of re-arrest for assault during the fixed follow-up period, (2) lower likelihoods of re-arrest during each month of follow-up, and (3) longer delays to re-arrest (for those who ultimately re-offend). Also, shorter delays to divorce filings (after initial arrest) were more effective for reducing likelihoods of subsequent assault, particularly within the first 11 months after arrest. Although marriage may serve to inhibit future criminality among some types of offenders,18 marital “stability” may have the direct opposite effect in the context of understanding repeat involvement in intimate assault. These observations underscore the potential relevance of Gottfredson and Hirschi's theory of low self control, particularly their conceptual interaction between low control and opportunity, for understanding domestic violence by adults.11

From a policy perspective, the findings described here have potential implications for victim support services offered through domestic violence courts. Not only is there evidence that women who file for divorce may significantly reduce their odds of re-victimization, but (perhaps more importantly) there is evidence to suggest that the swiftness of divorce proceedings may further reduce these odds. Assuming that additional research ratifies these findings, such information will provide additional incentives for support personnel to target and overcome the barriers noted earlier that prevent many women from successfully filing for divorce. The finding that only 24% of the sample were involved in divorce proceedings during the study period could reflect the magnitude of these barriers.

Jaffe and Crooks described the challenges faced by battered women when they try to access legal services, underscoring the importance of domestic violence courts for facilitating such access.19 The services of these courts also may be important for women concerned with child custody issues. For example, Kernic found that even though a person's history of IPV is supposed to be considered in child custody decisions, victims were no more likely to be awarded custody than non-victims.20 Further complicating the problem, separate studies have found that 20% of battered women return to their husbands because these men threaten to take and/or harm their children.21,22 Economic hardship is also a major consideration for women contemplating divorce, providing yet another potentially important role for domestic violence courts.23 Davis estimated that 50% to 90% of IPV victims make some attempt to leave their partners, but end up staying due to financial considerations.24

An important caveat to this discussion is that additional research on the subject is absolutely necessary due to our limited scope of analysis. In their research on domestic violence and the risk of homicide, Dugan and her colleagues underscored the need to establish services for domestic violence victims that do not unintentionally increase the odds of retaliation by abusers.2,3 Our findings are clearly limited by a focus on men who were initially arrested for misdemeanor assaults, and so the effectiveness or unanticipated ineffectiveness of expediting divorce proceeding against felons remains unknown. Moreover, our analysis of a single metropolitan jurisdiction raises the possibility that the effects of divorce proceedings might vary across different geographic regions and socio-political contexts.

Additional research is also needed to provide insight into important questions raised by our analysis. Some of these questions include who actually filed for divorce and the reasons why; did either partner receive further interventions (legal, social, or clinical) that might be related to both filing for divorce and the odds of re-assault; did re-assault occur without re-arrest; and whether men with new female partners were violent towards them. The study described here should therefore be seen as offering preliminary findings on a potentially important issue.

Footnotes

Some of the data examined for this paper are available from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). Data for “Reconsidering Domestic Violence Recidivism: Individual and Contextual Effects of Court Dispositions and Stake in Conformity in Hamilton County, Ohio 1993–1998” were collected by John Wooldredge. The Consortium bears no responsibility for the analyses presented here.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell J, Rose L, Kub J, Nedd D. Voices of strength and resistance: a contextual and longitudinal analysis of women's responses to battering. J Interpers Violence. 1998;13:743–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dugan L, Nagin D, Rosenfeld R. Explaining the decline in intimate partner homicide: the effects of changing domesticity, women's status, and domestic violence resources. Homicide Studies. 1999;3:187–214. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dugan L, Nagin D, Rosenfeld R. Exposure reduction or retaliation? The effects of domestic violence resources on intimate partner homicide. Law and Society Rev. 2003;37:169–98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gover A, MacDonald J, Alpert G. Combating domestic violence: findings from an evaluation of a local domestic violence court. Criminology and Public Policy. 2003;3:109–29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachman R, Saltzman L. Violence against women: estimates from the redesigned survey. Special Report. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1995. Aug, Report No.: NCJ-154348. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiwak R, Brownridge D. Separated women's risk for violence: an analysis of the Canadian situation. J Divorce Remarriage. 2005;43:105–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butts-Stahly G. Women with children in violent relationships: the choice of leaving may bring the consequence of custodial challenge. J Aggression Maltreat Trauma. 1999;2:239–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson M, Daly M. Sexual rivalry and sexual conflict: recurring themes in fatal conflicts. Theoretical Criminology. 1998;2:291–310. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catlett B, Artis J. Critiquing the case for marriage promotion. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:1226–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helling J. Specialized criminal domestic violence courts. Violence Against Women Online Resources. 1999. [cited 2006 May 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.vaw.umn.edu/documents/helling/helling.html.

- 11.Gottfredson M, Hirschi T. A general theory of crime. Stanford (CA): Stanford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wooldredge J, Thistlethwaite A. Reconsidering domestic violence recidivism: conditioned effects of legal controls by individual and aggregate levels of stake in conformity. J Quantitative Criminology. 2002;18:45–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wooldredge J, Thistlethwaite A. Final report. Washington: National Institute of Justice; 1999. Reconsidering domestic violence recidivism: individual and contextual effects of court dispositions and stake in conformity. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clerk of Courts, Hamilton County, Ohio. [cited 2006 Apr 25]. Available from: URL: http://www.courtclerk.og/cpciv_namesearch.asp.

- 15.Campbell J. Assessing dangerousness in domestic violence cases: history, challenges, and opportunities. Criminology and Public Policy. 2005;4:653–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman L, Smith D, Schmidt J, Rogan D. Crime, punishment, and stake in conformity: legal and informal control of domestic violence. Am Sociol Rev. 1992;57:680–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berk R, Newton P. Does arrest really deter wife battery? An effort to replicate the findings of the Minneapolis Spouse Abuse Experiment. Am Sociol Rev. 1985;50:253–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sampson R, Laub J. Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaffe P, Crooks C. Understanding women's experiences parenting in the context of domestic violence: implications for community and court-related service providers. [cited 2005 Apr];Violence Against Women Online Resources. 2005 Available from: URL: http://www.vaw.umn.edu/documents/commissioned/parentingindv/parentingindv.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kernic M, Monary-Ernsdorff D, Koepsell J, Holt V. Children in the crossfire: child custody determinations among couples with a history of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:991–1021. doi: 10.1177/1077801205278042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liss M, Stahly G. Domestic violence and child custody. In: Hansen M, Harway M, editors. Battering and family therapy: a feminist perspective. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zorza J. How abused women can use the law to help protect their children. In: Peled E, Jaffe PG, Edleson JL, editors. Ending the cycle of violence: community responses to children of battered women. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 147–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dee T. Until death do us part: the effects of unilateral divorce on spousal homicides. Econ Inq. 2003;41:163–83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis M. The economics of abuse: how violence perpetuates women's poverty. In: Brandwein RA, editor. Battered women, children, and welfare reform: the ties that bind. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]