Abstract

We designed a method by which to generate antibiotic-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae at frequencies 4 orders of magnitude greater than the spontaneous mutation rate. The method is based on the natural ability of this organism to be genetically transformed with PCR products carrying sequences homologous to its chromosome. The genes encoding the targets of ciprofloxacin (parC, encoding the ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV), rifampin (rpoB, encoding the β subunit of RNA polymerase), and streptomycin (rpsL, encoding the S12 ribosomal protein) from susceptible laboratory strain R6 were amplified by PCR and used to transform the same strain. Resistant mutants were obtained with a frequency of 10−4 to 10−5, depending on the fidelity of the DNA polymerase used for PCR amplifications. Ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants, for which the MICs were four-to eightfold higher than that for R6, carried a single mutation of a residue in the quinolone resistance-determining region: S79 (change to A, F, or Y) or D83 (change to N or V). Rifampin-resistant strains, for which the MICs were at least 133-fold higher than that for R6, contained a single mutation within cluster I of rpoB: S482 (change to P), Q486 (change to L), D489 (change to V), or H499 (change to L or Y). Streptomycin-resistant mutants, for which the MICs were at least 64-fold higher than that for R6, carried a mutation at either K56 (change to I, R, or T) or K101 (change to E). PCR products obtained from the mutants were able to transform R6 to resistance with high efficiency (>104). This method could be used to efficiently obtain resistant mutants for any drug whose target is known.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the human pathogen responsible for most community-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, and otitis media, causing about three million deaths annually in children in developing parts of the world (15). Since the 1990s, the number of pneumococcal clinical isolates resistant to the major therapeutic drugs, including new ones such as the fluoroquinolones (5, 27), has been increasing worldwide (9, 18, 33) and is becoming a major problem for public health. In this scenario, studies on the mechanisms involved in antibiotic resistance are of primary importance. These studies rely mainly on the identification of antibiotic targets by locating the mutations involved in resistance and on biochemical studies of inhibition mechanisms. A significant advance in this direction has been the determination of the complete genome sequences of laboratory pneumococcal strain R6 (19) and a serotype 4 isolate (40) and most of that of a serotype 19F isolate (7). Deciphering the role of these genomic sequences entails the generation of a large amount of theoretical information that must be corroborated experimentally by molecular biology. However, molecular methods for S. pneumoniae are still limited (22) despite its clinical significance. On the other hand, it is well known that S. pneumoniae is a naturally competent bacterium and methods for its transformation under laboratory conditions have been developed. The state of competence is a process dependent on cell density triggered by the accumulation in the medium of the competence-stimulating peptide that signals the two-component ComD-ComE system (16, 35), which results in the transcriptional activation of a competence-specific sigma factor (26). This factor enables transcription of the late competence genes that encode enzymes for the binding, uptake, and recombination of the donor DNA with the chromosome (3, 24, 36).

We have recently obtained several mefloquine-resistant pneumococcal mutants by using PCR amplification of fragments of the genes atpC and atpA, which encode the c and a subunits of the F0F1 ATPase, respectively (10, 29). Transformation with these PCR products obtained from strain R6 and selection of transformants in inhibitory mefloquine concentrations rendered mutants at a frequency several orders of magnitude greater than the spontaneous mutation rate. The information provided by the new mutants has significantly contributed to our understanding of the arrangement of the F0F1 ATPase (28). It was proposed that those mutants originated as a result of the error rate of the DNA polymerase used in the PCR amplifications (28). In this work, we present evidence supporting this hypothesis and that the method is useful for obtaining S. pneumoniae mutants at high frequency with mutations in at least three genes, parC, rpoB, and rpsL, known to be targets of ciprofloxacin (CIP) (20, 30, 34, 39), rifampin (RIF) (8, 32), and streptomycin (STR) (37), respectively.

While this report was in preparation, a PCR-based approach to drug target identification in S. pneumoniae was published (2). Although PCR methodology and the natural transformability of the pneumococcus are the bases of both studies, our work has been focused on the generation and characterization of antibiotic-resistant pneumococcal transformants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth and transformation of bacteria.

The S. pneumoniae strains used in this study were laboratory strain R6, ATCC 49619, STR-resistant (Strr) strain 533 (str-41 sul nov-1 ery) (25), and CIP-resistant (Cipr) clinical isolate 4114. S. pneumoniae was grown in a casein hydrolysate-based medium with 0.2% sucrose (AGCH) as the energy source and transformed as previously described (23). Strain R6 was used as the recipient in transformation experiments. Cultures containing 9 × 106 CFU per ml were treated with DNA at 0.15 μg/ml for 40 min at 30°C and then at 37°C for 90 min before plating on medium plates containing 2 μg of CIP per ml, 1 μg of RIF per ml, or 100 μg of STR per ml. Colonies were counted after 24 h of growth at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in AGCH medium with 1% agar. Rates of spontaneous mutation to drug resistance were estimated by plating 2 × 1010 cells in 1 μg of RIF per ml or 100 μg of STR per ml.

DNA techniques.

S. pneumoniae chromosomal DNA was prepared as previously described (14). Synthetic oligonucleotide primers used in PCR amplifications and in sequencing reactions are listed in Table 1 and were designed on the basis of the previously published sequences of the corresponding genes of strain R6 (11, 19, 30). Amplifications were performed with 1 U of Thermus thermophilus (Tth) thermostable DNA polymerase (Biotools) or 2.5 U of a proofreading enzyme, the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Hf; Boehringer Manheim), 1 μg of genomic DNA, the corresponding synthetic oligonucleotide primers at 0.4 μM each, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2 mM MgCl2 in a final volume of 50 μl. Amplification was carried out with an initial cycle of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C; 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 90 s at 55°C, and a 75-s polymerase extension step at 72°C; and a final 8-min 72°C extension step, followed by slow cooling to 4°C. The remaining deoxynucleoside triphosphates and primers were removed from PCR products with HR S-400 columns (Amersham) prior to sequencing or transformation. Sequencing was done on both DNA strands with an Applied Biosystems Prism 377 DNA sequencer in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Nucleotide (amino acid) positionsa |

|---|---|---|

| parCUP | GAACACGCCCTAGATACTGTG | −103 to −83 of parC |

| parC50 | AAGGATAGCAATACTTT | 147-163 of parC (50KDSNTF55) |

| parC152 | GTTGGTTCTTTCTCCGTATCG | Complementary to 456-438 of parC (147DTEKEP152) |

| parC503R | GCCTTGGTCACGCTGACGTAGG | Complementary to 1526-1505 of parC (502TYVSVTKA509) |

| rpoB227 | GCGAATTGGTTCGCAACACTG | 680-700 of rpoB (227ELVRNT233) |

| rpoB427 | CGGTTGGTGAATTGCTTGCCAACC | 1282-1306 of rpoB (427AVGELLAN435) |

| rpoB554R | CAAGTGTCCGTAAGATGCAAG | Complementary to 1641-1662 of rpoB (548LSSYGHL554) |

| rpoB773R | GTCATGTAGGCAACGATTGGG | Complementary to 2322-2301 of rpoB (768PIVAYMT774) |

| rpsLUP | GGGCTAGTAGAAGTAGTTGGC | 320-300 of spr0247 (101PTTSTSP107) |

| rpsL6 | CCAATTGGTTCGCAAACCGCG | 15-35 of rpsL (6QLVRKPR12) |

| rpsL131R | CCGTATTTAGAACGGCCTTG | Complementary to 392-373 of rpsL (125QGRSKYG131) |

| rpsLDOWN | CGGAAGTGTGCGAATGCACGG | Complementary to 443-426 of rpsG (143RMAEANR149) |

Nucleotide and amino acid numbering refers to the genes and proteins obtained from the S. pneumoniae R6 sequence, with the first nucleotide or amino acid at position 1.

MIC determination.

MICs were determined by the microdilution method with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco) supplemented with 2.5% lysed horse blood as recommended by the NCCLS (31). Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Difco) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood were used to grow the strains overnight. The inoculum was prepared by suspension of several colonies in Mueller-Hinton broth and adjusting the turbidity to a 0.5 McFarland standard (ca. 108 CFU/ml). The suspension was further diluted to provide a final bacterial concentration of 104 CFU/ml in each well of the microdilution trays. Plates were covered with plastic tape and incubated in ambient atmosphere at 37°C for 20 to 24 h. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of a drug that inhibited visible growth. S. pneumoniae strains ATCC 49619 and R6 were used for quality control. CIP was kindly provided by Bayer (Barcelona, Spain), whereas RIF and STR were purchased from Sigma.

RESULTS

Construction of resistant strains by PCR and transformation.

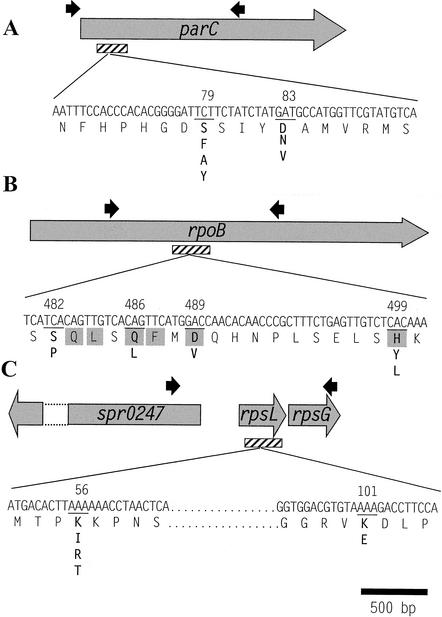

Fragments of about 1,600 bp were amplified by PCR from S. pneumoniae R6 by using the specific oligonucleotides parCUP and parC503R for parC, rpoB227 and rpoB773R for rpoB, and rpsLUP and rpsLDOWN for rpsL (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The 1,629-bp parC PCR fragment has the sequence encoding the first 508 amino acid residues of the 824-residue ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV and includes the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR; 30). The 1,641-bp rpoB PCR fragment codes for 547 residues (residues 227 to 554) of the central region of the β subunit of the RNA polymerase. The 1,615-bp rpsL PCR fragment includes the coding region for the first 320 residues of Spr0247, a putative alkaline amylopullulanase; the rpsL gene that encodes the 137-residue-long 30S ribosomal protein S12; and most (149 residues out of 156) of the 30S ribosomal protein S7 encoded by the rpsG gene. These R6 PCR-derived fragments were used to transform competent R6 cells, and transformants were selected on CIP at 2 μg/ml (4 times the MIC for R6), RIF at 1 μg/ml (more than 33 times the MIC for R6), or STR at 100 μg/ml (32 times the MIC for R6). These antibiotic concentrations were chosen by taking into account the levels of resistance to these drugs achieved by single mutations in parC (30), rpoB (8, 32), and rpsL (37). The frequencies of resistant mutants obtained by transformation were 1 × 10−5 to 12.4 × 10−5 and 0.4 × 10−5 to 6.4 × 10−5 when PCR products amplified with the Tth and Hf enzymes, respectively, were used (Table 2). As a consequence, two- to fourfold more transformants appeared when the Tth enzyme was used, which is consistent with the error rate differences (threefold) of these polymerases reported by the manufacturers. Transformants resistant to a particular antimicrobial agent appeared only when the corresponding target gene was present in the PCR product used as the donor DNA, whereas no colonies were detected when other antimicrobial agents were used for selection (Table 2). In this way, transformants resistant to either CIP, RIF, or STR appeared when the PCR products contained parC, rpoB, or rpsL, respectively. The MICs for the mutant strains showed increases in resistance of 4- to 8-fold for CIP, at least 133-fold for RIF, and at least 64-fold for STR (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Locations of the PCR products employed in this work, of the regions sequenced, and of the mutations present in the Cipr (A), Rifr (B), and Strr (C) strains. Black arrows (not draw to scale) indicate the oligonucleotides used to amplify the fragments of about 1,600 bp used in PCR experiments. Hatched rectangles correspond to the regions that were sequenced to identify the mutations. Amino acid substitutions present in the resistant strains are shown (in boldface) below the wild-type residue positions (underlined).

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic-resistant R6 transformants obtained with R6 PCR products

| Donor DNA | Enzyme | No. of transformants/ml (transformation frequency, 10−5) selected ona:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | RIF | STR | ||

| parC | Tth | 94 ± 21 (1.0) | None | None |

| Hf | 33 ± 22 (0.4) | None | None | |

| rpoB | Tth | None | 1,119 ± 319 (12.4) | None |

| Hf | None | 580 ± 193 (6.4) | None | |

| rpsL | Tth | None | None | 299 ± 88 (3.2) |

| Hf | None | None | 72 ± 28 (0.8) | |

Samples (0.15 μg) of PCR products carrying the genes indicated were used to transform 1 ml (9 × 106 CFU) of a competent R6 culture. Values (mean ± standard deviation) of three independent experiments are presented. The transformation frequency is the number of transformants divided by the total number of cells. None indicates that no transformants were observed when 300 μl of the transformation mixture was plated on selective plates, which gave a frequency <4 × 10−7. PCR products used as controls were a parC PCR product from S. pneumoniae 4114 carrying an S79F change that yielded 2.0 × 104 ± 1.5 × 104 transformants/ml and an rpsL PCR product from S. pneumoniae 533 (25) carrying a K56R (37) change that yielded 5.8 × 105 ± 2.8 × 105 transformants/ml.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of resistant strains

| Drug and strain (no. of clones) | Gene | Amino acid (codon) changea | MIC (μg/ml) (fold increase)b | No. of trans- formants/ ml (104)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | ||||

| CMJ1 (4) | parC | S79F (TCT→TTT) | 4 (8) | 4 |

| CMJ2 (1) | parC | D83N (GAT→AAT) | 2 (4) | 6 |

| CMJ3 (1) | parC | S79A (TCT→GCT) | 2 (4) | 10 |

| CMJ4 (2) | parC | S79Y (TCT→TAT) | 4 (8) | 27 |

| CMJ10 (1) | parC | D83V (GAT→GTT) | 2 (4) | 2 |

| RIF | ||||

| RMJ1 (5) | rpoB | Q486L (CAG→CTG) | 16 (>533) | 140 |

| RMJ3 (1) | rpoB | H499Y (CAC→TAC) | 8 (>266) | 13 |

| RMJ4 (1) | rpoB | H499L (CAC→CTC) | 16 (>533) | 43 |

| RMJ5 (2) | rpoB | S482P (TCA→CCA) | 4 (>133) | 14 |

| RMJ7 (1) | rpoB | D489V (GAC→GTC) | 16 (>533) | 48 |

| STR | ||||

| SMJ1 (2) | rpsL | K56I (AAA→ATA) | >800 (>256) | 16 |

| SMJ2 (6) | rpsL | K56R (AAA→AGA) | >800 (>256) | 7 |

| SMJ4 (1) | rpsL | K56T (AAA→ACA) | >800 (>256) | 27 |

| SMJ6 (1) | rpsL | K101E (AAA→GAA) | 200 (64) | 43 |

The amino acid positions of the genes indicated are according to the S. pneumoniae R6 genomic sequence. Mutated nucleotides are underlined.

The MICs shown are averages of four independent determinations. Each value in parentheses is the MIC for the resistant strain divided by the MIC for R6 (0.5 μg of CIP per ml, <0.03 μg of RIF per ml; and 3.12 μg of STR per ml).

PCR products carrying parts of the indicated genes from resistant strains were used to transform R6 competent cells. PCR products used as controls were those indicated in Table 2.

Characterization of antibiotic-resistant strains.

Ten resistant mutants for each antibiotic were chosen, and pertinent regions (Fig. 1) of the parC, rpoB, and rpsL genes were sequenced. A region of 310 bp encoding ParC residues 50 to 172 was amplified and sequenced with oligonucleotides parC50 and parC152 (Table 1). The 10 Cipr strains carried single mutations affecting residue S79 or D83 of the ParC QRDR (Table 3). A 380-bp region of rpoB coding for residues 427 to 554 was amplified and sequenced with oligonucleotides rpoB427 and rpoB554R. The RIF-resistant (Rifr) strains carried mutations affecting residue S482, Q486, D489, or H499. A 378-bp fragment of rpsL encoding residues 6 to 131 of the S12 ribosomal protein from the Strr strains was also amplified and sequenced with oligonucleotides rpsL6 and rpsL131R, showing mutations that would produce changes at K56 or K101.

Genetic evidence demonstrating that the mutations carried by the resistant strains were indeed involved in resistance was obtained by genetic transformation. PCR products of about 1,600 bp amplified from the Cipr, Rifr, and Strr strains described above were able to transform strain R6 to resistance highly efficiently (0.2 × 105 to 14 × 105 transformants/ml) (Table 3). Two independent colonies from each of these transformation experiments were selected and analyzed. Their MICs and mutations were identical to those of the parental Cipr, Rifr, or Strr strain (not shown). These results confirmed the relationship between amino acid changes and resistance phenotypes.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe a simple method by which to obtain antibiotic-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae by taking advantage of the PCR method, the error rate of the DNA polymerases used in the amplifications, and the natural transformation ability of S. pneumoniae. The appearance of resistant colonies upon transformation with the 1,600-bp PCR products carrying the appropriate R6 genes could be attributed to the error rate of the polymerase. This rate is 1 error/10 kb; therefore, 1.6 errors would be expected for 10 molecules of 1,600 bp. Since 4.5 × 105 competent cells (5% of 9 × 106 CFU) could be transformed with chromosomal DNA in our experiments, the total number of putative mutants would be about 7.2 × 104. On the basis of our results, of the putative nucleotide changes that would occur in the parC PCR fragment (encoding 508 residues of ParC) and in the rpsL PCR fragment (encoding 320 residues of Spr0247, 137 residues of RpsL, and 149 residues of RpsG), only changes at two positions conferred CIP resistance (0.4%) or STR resistance (0.3%). However, of the putative nucleotide changes that would occur in the rpoB PCR fragment (encoding 547 residues of the β subunit of RNA polymerase), changes at four positions conferred RIF resistance (0.7%) (Table 3). If we introduced these corrections, among 7.2 × 104 putative mutants, the expected numbers of resistant clones would be approximately 3 × 102 Cipr, 2 × 102 Strr, and 5 × 102 Rifr clones. These values are consistent with the numbers of drug-resistant clones (0.9 × 102 Cipr, 3 × 102 Strr, and 1 × 103 Rifr clones) obtained and are also in line with those previously reported for RIF and STR (2) and with the frequencies reported for mefloquine-resistant mutants (28).

The method allowed us to obtain mutants at frequencies several orders of magnitude higher than that of spontaneous mutation. The frequency of mutation to Cipr, Rifr, and Strr in S. pneumoniae has been shown to be in the range of 10−8 to 10−9 (2, 34; our own results), whereas the Cipr, Rifr, and Strr transformation frequencies obtained with the corresponding PCR products were about 10−5, 10−4, and 10−5, respectively (Table 3).

Among the 10 mutants sequenced that were resistant to each antibiotic, 5 different Cipr, 5 different Rifr, and 4 different Strr mutations were obtained. All of the ParC QRDR mutations found in the Cipr strains obtained in this work had been previously described in laboratory or clinical isolates (1, 6, 20, 30, 34, 39). Although S79F and S79Y have been shown to be involved in resistance by transformation (20, 30, 39), the results presented in this work represent the first evidence that the S79A, D83N, and D83V changes are involved in low-level CIP resistance.

All of the pneumococcal Rifr strains obtained in this work had mutations in cluster I of rpoB (R6 residue positions 478 to 510), a conserved region where most of the bacterial Rifr mutations map (reference 4 and references cited therein) and also where Rifr mutations have been characterized in S. pneumoniae clinical isolates (8, 32). The Rifr mutations found in this work were at residues S482, Q486, D489, and H499 (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Structural and biochemical studies of the Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase have revealed that RIF binds to a pocket of the RNA polymerase β subunit deep within the DNA-RNA channel and blocks the path of the elongating RNA when the transcript becomes two or three nucleotides long. Ten residues of cluster I are directly implicated in the interaction with RIF (4, 41). These residues are identical among Escherichia coli, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and S. pneumoniae (six of them are shadowed in Fig. 1). Three of these residues are equivalent to those found to be mutated in Rifr S. pneumoniae that established hydrogen bonds with the antibiotic (Q486, D489, and H499). These results suggest that the binding of RIF to S. pneumoniae RNA polymerase is similar in all bacterial enzymes. Accordingly, mutations altering D489 and H499 have been found in Rifr S. pneumoniae clinical isolates (8, 32) and those altering the Q residue equivalent to S. pneumoniae R6 Q486 have been shown to be involved in Rifr in E. coli (21, 38) and M. tuberculosis (17). However, no mutations at the residue equivalent to S482 of S. pneumoniae have been previously reported in other Rifr bacteria (reference 4 and references cited therein). This residue does not interact directly with RIF, although it is conserved among bacterial β subunits and is in close proximity to the RIF binding pocket (4). The change of S482 to proline conferred low-level RIF resistance (MIC = 4 μg/ml) to strain RMJ4 (Table 3) and might affect the folding or packing of the protein in the vicinity of this residue, causing distortions of the RIF binding pocket, as has been proposed for other Rifr mutations that also map to residues surrounding this pocket (4).

With respect to the Strr strains, mutations were found at two lysine residues, K56 and K101 (equivalent to K42 and K87 of E. coli). These two residues have been shown to be involved in Strr in E. coli (13) and M. tuberculosis (reference 12 and references therein), and the K56T change has been shown to be responsible for the Strr phenotype of S. pneumoniae 533 (37).

In summary, with the method described in this work, it was possible to construct Cipr, Rifr, and Strr strains carrying mutations in specific gene regions. The same method might be used to construct all possible mutants resistant to other drugs. It would also be possible to make double mutants by sequential PCR and transformation cycles. Strains resistant to two (or more) antibiotics of the same family can be obtained in this way. The activity of the various antibiotics could be tested in the mutants obtained. This information would be useful in selecting more adequate therapy, ideally with antibiotics not showing cross-resistance.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. García for critical reading of the manuscript. The technical assistance of Amaya Aguirre is acknowledged.

A.J.M.-G. is the recipient of a fellowship from the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid. This study was supported by grant 1274/01 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, grant 00/0258 from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, and grant BIO2002-01398 from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bast, D. J., D. E. Low, C. Duncan, L. Kilburn, L. A. Mandell, R. J. Davidson, and J. C. S. de Azevedo. 2000. Fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: contributions of type II topoisomerase mutations and efflux to levels of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3049-3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belanger, A. E., A. Lai, M. A. Brackman, and D. J. LeBlanc. 2002. PCR-based ordered genomic libraries: a new approach to drug target identification for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2507-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell, E. A., S. Y. Choi, and H. R. Masure. 1998. A competence regulon in Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed by genome analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 27:929-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell, E. A., N. Korzheva, A. Mustaev, K. Murakami, S. Nair, A. Goldfarb, and S. A. Darst. 2001. Structural mechanism for rifampicin inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerases. Cell 23:901-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, D. K., A. McGeer, J. C. de Azavedo, and D. E. Low. 1999. Decreased susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies, T. A., G. A. Pankuch, B. E. Dewasse, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1999. In vitro development of resistance to five quinolones and amoxicillin-clavulanate in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1177-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dopazo, J., A. Mendoza, J. Herrero, F. Caldara, Y. Humbert, L. Friedli, M. Guerrier, E. Grand-Schenk, C. Gandin, M. de Francesco, A. Polissi, G. Buell, G. Feger, E. García, M. Peitsch, and J. F. García-Bustos. 2001. Annotated draft genomic sequence from a Streptococcus pneumoniae type 19F clinical isolate. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:99-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enright, M., P. Zawadski, P. Pickerill, and C. G. Dowson. 1998. Molecular evolution of rifampicin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 4:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenoll, A., I. Jado, D. Vicioso, A. Pérez, and J. Casal. 1998. Evolution of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes and antibiotic resistance in Spain: update (1990-1996). J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3447-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenoll, A., R. Muñoz, E. García, and A. G. de la Campa. 1994. Molecular basis of the optochin-sensitive phenotype of pneumococcus: characterization of the genes encoding the F0 complex of the Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus oralis H+-ATPases. Mol. Microbiol. 12:587-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrándiz, M. J., A. Fenoll, J. Liñares, and A. G. de la Campa. 2000. Horizontal transfer of parC and gyrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:840-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finken, M., P. Kirschner, A. Meier, A. Wrede, and E. C. Böttger. 1993. Molecular basis of streptomycin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: alterations of ribosomal protein S12 and point mutations within a functional 16S ribosomal RNA pseudoknot. Mol. Microbiol. 9:1239-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funatsu, G., and H. G. Wittmann. 1972. Location of amino acid replacements in protein S12 isolated from Escherichia coli mutants resistant to streptomycin. J. Mol. Biol. 68:547-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González, I., M. Georgiou, F. Alcaide, D. Balas, J. Liñares, and A. G. de la Campa. 1998. Fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in the parC, parE, and gyrA genes of clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2792-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwood, B. 1999. The epidemiology of pneumococcal infection in children in the developing world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 354:777-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Håvarstein, L. S., G. Coomaraswamy, and D. A. Morrison. 1995. An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11140-11144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heep, M., B. Brandstätter, U. Rieger, N. Lehn, E. Richter, S. Rüsch-Gerdes, and S. Nieman. 2001. Frequency of rpoB mutations inside and outside the cluster I region in rifampin-resistant clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:107-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman, J., M. S. Cetron, M. M. Farley, W. S. Baughman, R. R. Facklam, J. A. Elliot, K. A. Deaver, and R. F. Breiman. 1995. The prevalence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Atlanta. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:481-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D. J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, H. Khoja, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. W. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, M. O'Gara, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P. M. Sun, M. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, S. R. Jaskunas, P. R. Rosteck, P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janoir, C., V. Zeller, M.-D. Kitzis, N. J. Moreau, and L. Gutmann. 1996. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2760-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin, D. J., and C. A. Gross. 1988. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 202:45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacks, S. 2000. Cloning and expression of pneumococcal genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae, p. 67-77. In A. Tomasz (ed.), Streptococcus pneumoniae: molecular biology and mechanism of disease. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., Larchmont, N.Y.

- 23.Lacks, S. A. 1966. Integration efficiency and genetic recombination in pneumococcal transformation. Genetics 53:207-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacks, S. A., S. Ayalew, A. G. de la Campa, and B. Greenberg. 2000. Regulation of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae: expression of dpnA, a late competence gene encoding a DNA methyltransferase of the DpnII restriction system. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1089-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacks, S. A., and B. Greenberg. 1975. A deoxyribonuclease of Diplococcus pneumoniae specific for methylated DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 250:4060-4066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, M. S., and D. A. Morrison. 1999. Identification of a new regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae linking quorum sensing to competence for genetic transformation. J. Bacteriol. 181:5004-5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liñares, J., A. G. de la Campa, and R. Pallarés. 1999. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1546-1547. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Martín-Galiano, A. J., B. Gorgojo, C. M. Kunin, and A. G. de la Campa. 2002. Mefloquine and new related compounds target the F0 complex of the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1680-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martín-Galiano, A. J., M. J. Ferrándiz, and A. G. de la Campa. 2001. The promoter of the operon encoding the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is inducible by pH. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1327-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muñoz, R., and A. G. de la Campa. 1996. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of fluoroquinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2252-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NCCLS. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A4. NCCLS, Villanova, Pa.

- 32.Padayachee, T., and K. Klugman. 1999. Molecular basis of rifampin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2361-2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pallarés, R., J. Liñares, M. Vadillo, C. Cabellos, F. Manresa, P. F. Viladrich, R. Martin, and F. Gudiol. 1995. Resistance to penicillin and cephalosporins and mortality from severe pneumococcal pneumonia in Barcelona, Spain. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:474-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan, X.-S., J. Ambler, S. Mehtar, and L. M. Fisher. 1996. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2321-2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pestova, E. V., L. S. Håvarstein, and D. A. Morrison. 1996. Regulation of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae by an auto-induced peptide pheromone and a two-component regulatory system. Mol. Microbiol. 21:853-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pestova, E. V., and A. D. Morrison. 1998. Isolation and characterization of three Streptococcus pneumoniae transformation-specific loci by use of a lacZ reporter insertion vector. J. Bacteriol. 180:2701-2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salles, C., L. Créancier, J.-P. Claverys, and V. Méjean. 1992. The high level streptomycin resistance gene from Streptococcus pneumoniae is a homologue of the ribosomal protein S12 gene from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:6103.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Severinov, K., M. Soushko, A. Goldfarb, and V. Nikiforov. 1993. Rifampicin region revisited: new rifampicin-resistant and streptolydigin-resistant mutants in the β subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14820-14826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tankovic, J., B. Perichon, J. Duval, and P. Courvalin. 1996. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2505-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang, G., E. A. Campbell, L. Minakhin, C. Ritcher, K. Severinov, and S. A. Darst. 1999. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase at 3.3 Å resolution. Cell 98:811-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]