Abstract

The response regulator EvgA controls expression of multiple genes conferring antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli (K. Nishino and A. Yamaguchi, J. Bacteriol. 184:2319-2323, 2002). To understand the whole picture of EvgA regulation, DNA macroarray analysis of the effect of EvgA overproduction was performed. EvgA activated genes related to acid resistance, osmotic adaptation, and drug resistance.

Bacteria have developed signaling systems for eliciting a variety of adaptive responses to their environment. These adaptive responses are often mediated by two-component regulatory systems, generally consisting of a sensor kinase and a response regulator (1, 17, 35, 36, 45). In a previous study, Nishino and Yamaguchi found that the EvgAS two-component system modulates drug resistance of Escherichia coli by regulating the expression of drug transporters (32, 33). The response regulator EvgA modulates the expression of emrKY (20), which encodes a bile salt-specific exporter (31, 33), and yhiUV, which encodes a multidrug exporter (31, 32). Overexpression of EvgA in the background of a deficiency of E. coli major multidrug exporter AcrB (25) confers drug resistance against antibiotics, dyes, and bile salts (33). EvgA also significantly regulates the expression of yfdX, whose function is unknown (32, 33). However, the physiological role of the EvgAS system is unknown.

We hypothesized that EvgA must control the expression of a wide range of genes.

E. coli macroarrays have been successfully used to quantify the entire complement of individual mRNA transcripts (5, 7, 44, 46). Therefore, in order to reveal the whole picture of the EvgA-controlled genes, macroarray analysis of the effect of EvgA overproduction was employed in this study.

Effect of overexpression of evgA on gene expression.

DNA macroarrays, which contain most of the genomic open reading frames of E. coli (8), allowed comprehensive studies on EvgA-controlled E. coli gene expression. The strain NK1230 has a single copy of evgA in its chromosome and harbors a mock plasmid, pUC119, while NK1231 bears high-copy-number plasmid pUCA, which carries the evgA gene (Table 1). The growth rates of the two strains were indistinguishable (data not shown). The comprehensive transcript profiles of these two strains prepared from exponential-phase cells were compared as follows. Cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (41) and were rapidly collected for total RNA extraction when the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6. Total RNA was isolated by using an RNeasy Protect Bacteria Mini kit (Qiagen). 33P-labeled cDNAs were prepared from RNA extracted from NK1230 and NK1231 by using cDNA-labeling primers (Sigma-Genosys). Labeled cDNAs were hybridized to the Panorama E. coli gene arrays (Sigma-Genosys), and phosphorimager files and autoradiograms were obtained according to the manufacturer's instructions as described previously (7, 46). The increased evgA gene dosage in NK1231 resulted in a 41.8-fold elevation of cognate evgA transcripts, and the expression of 23 genes (open reading frames) was elevated more than fourfold while the expression of 3 genes was repressed by a factor of at least 4 (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

TABLE 2.

E. coli genes whose relative expression levels were increased or decreased by evgA amplification

| Genea | b no.b | Functional classificationc | Known or predicted function | Effect of EvgA on gene expression (fold change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased expression | ||||

| hdeAd,e | b3510 | Not known | Protein regulated by H-NS, chaperone | 84.3 |

| yfdX | b2375 | Not known | Protein regulated by EvgA | 54.4 |

| hdeBd,e | b3509 | Not known | Protein regulated by H-NS, predicted chaperone | 42.2 |

| evgAe | b2369 | Regulation | Regurator of EvgAS two-component system | 41.8 |

| gadAd,e | b3517 | Metabolism | Glutamate decarboxylase-alpha | 41.4 |

| ydePe | b1501 | Metabolism | Putative reductase | 15.3 |

| yjfL | b4184 | Cell structure | Putative membrane protein | 9.2 |

| yfdWe | b2374 | Metabolism | Putative formyl-coenzyme A transferase | 6.8 |

| msyB | b1051 | None | Acidic protein suppresses mutants lacking function of protein export | 6.5 |

| dpse | b0812 | Adaptation (starvation) | Stress response DNA-binding protein | 6.3 |

| yhiEe | b3512 | Regulation | Putative regulator | 6.2 |

| ybjR | b0867 | Metabolism | Putative amidase | 5.5 |

| asr | b1597 | Adaptation (stress) | Acid shock RNA controlled by phoBR | 5.3 |

| yfdM | b2359 | Extrachromosomal (phage) | Putative transferase | 5.2 |

| gadC (xasA)d,e | b1492 | Transport | Predicted amino acid transporter | 5.2 |

| ypeC | b2390 | None | Function unknown | 5.2 |

| ycaC | b0897 | Metabolism | Putative cysteine hydrolase | 5.0 |

| yahO | b0329 | None | Function unknown | 4.7 |

| yfdO | b2358 | Extrachromosomal (phage) | Putative replication protein | 4.6 |

| yhiV | b3514 | Transport | Multidrug transport protein | 4.4 |

| ybaS | b0485 | Metabolism | Putative glutaminase | 4.3 |

| mgtA | b4242 | Transport | Magnesium transporter | 4.1 |

| yfdE | b2371 | Metabolism | Putative formyl-coenzyme A transferase | 4.0 |

| Decreased expression | ||||

| tnaA | b3708 | Metabolism | Tryptophan deaminase | 7.1 |

| tnaL | b3707 | Metabolism | Tryptophanase leader peptide | 5.0 |

| glpQ | b2239 | Metabolism | Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase | 4.5 |

Based on information from the EcoGene database (http://bmb.med.miami.edu/ecogene/ecoweb/) (40).

Blattner number. Based on information from the E. coli Genome Project database (http://www.genome.wisc.edu/) (8).

Based on information from the Gene ProtEC database (http://genprotec.mbl.edu/) (38, 39).

Previously shown to be important for acid survival.

Expression of these genes are increased in the H-NS-deficient strain (18).

Known genes in EvgA regulon.

In previous studies, Nishino and Yamaguchi reported that overproduction of EvgA increases the expression of yhiUV, emrKY, and yfdX (32, 33). In the DNA macroarray analysis, the enhancement of the gene expression of yhiU, yhiV, and yfdX was 1.8-, 4.4-, and 54.4-fold, respectively. Significant enhancement of emrK and emrY was not observed in the macroarray analysis. Therefore, we reinvestigated the EvgA-dependent induction of these genes by quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) as follows. Bulk cDNA samples were synthesized from total RNA derived from E. coli cells by using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (PE Applied Biosystems) and random hexamers as primers. A real-time PCR was performed with each specific primer pair (Table 3) by using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (PE Applied Biosystems). rrsA of the 16S rRNA gene was chosen as the normalizing gene. The reactions were run on an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems).

TABLE 3.

Primer pairs used to compare transcript levels

| Gene | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| emrK | GCGCTTAAACGTACGGATATTAAGA | ACTGTTTCGCCGACCTGAAC |

| emrY | GCTTTCTGGGAGCATCAACAG | CAGTAACAGGGATCGCAATGG |

| evgA | TTCTTGTTTCGATAAGGAGTCGAGTT | TGCTATTTCCCCTTCTCTCTCAAC |

| fimA | GGTGTGCAGATCCTGGACAGA | CGGAATGGTATTGGTTCCGTTA |

| fimF | GGGTTTACTGGCGTTGCAGAT | GAAGCCGCTGACACCGTATT |

| fimH | CGATGTTTCTGCTCGTGATGTC | GTTGTGCCGGAGAGGTAATACC |

| fimI | ACCGGTGCCTTTTGTTATTCAT | ACCGTGAAACGCCACACCTA |

| fliA | TTAGGGATCGATATTGCCGATT | CGTAGGAGAAGAGCTGGCTGTT |

| fliC | TCAGGCGGTACACCTGTTCAG | GCAGCGTAAAGATTGCCATTT |

| gadA | CGGCTTCGAAATGGACTTTG | TGGGCAATACCCTGCAGTTT |

| gadX | TTTATACCGCTGCTTCTGAACGT | GTGTCCACTCATGGGCGATATTA |

| hdeA | CTGCCAGTTGTGAGCAATGC | CTGCAGTTGGCTGGAAGGAT |

| hdeB | CACTGGTGAACGCACAATCTG | CTTCATGCAGCATCCACCAT |

| hdeD | ATGAAAGGCAGCTGGCTACAG | CCAGTGTGGAAACCAGCGTTA |

| hns | GCTGATCGCTGACGGTATTGA | GCTTTGGTGCCAGATTTAACG |

| rrsA | CGGTGGAGCATGTGGTTTAA | GAAAACTTCCGT GGATGTCAAGA |

| tolC | CCGGGATTTCTGACACCTCTT | TTTGTTCTGGCCCATATTGCT |

| yfdE | ATCAACCCGCGCCTCATAT | GCTCATTGCCTGAATGATGGT |

| yfdU | TGCCAATGTCTATGGCGAAAG | CGTGTGCCAATAACCAATTCA |

| yfdV | GAGTTCAGTGCCGAAATTGCTT | TGTTCGCTGTTCAAATGACATG |

| yfdW | GGCAACGAGTCACCATGTCA | AGACGCTGCTGGTCACGTAA |

| yfdX | ACGTCACGCATCGCATATAAAC | AGCAAGTTCAGCAAACCCAGAA |

| yhiE | TCATATCCTTGATGAAGAAGCGATT | GCGCTTTAGCTTTTAGTTTACTGATG |

| yhiU | CCCCCGGTTCGGTCAA | GGACGTATCTCGGCAACTTCAT |

| yhiV | TTACCGTCAGCGCTACCTATCC | GCCATCAAGCCCATTCATATTT |

| yhiW | CGAGAGTATTCTGCTGCTGGAGA | AGTAATGGCAAACTGTCAGCTCAT |

| ypdI | GGTCTCTATTATGGCATGCAATGT | ATCGCCTGTGATGGCTGAAG |

The degree of enhancement of expression of yhiU, yhiV, yfdX, emrK, and emrY was 250, 67, 1,600, 15, and 12, respectively (Table 4). The degree of induction measured by macroarray analysis was obviously lower than that measured by qRT-PCR, probably because the dynamic range of the former analysis is narrower than that of the latter measurement. The order of the degree of the enhancement was consistent between assays except for that of yhiU. The unexpectedly low induction of yhiU gene expression measured by the macroarray analysis might be due to the inefficient primers for yhiU used in this analysis. The detection limit of the enhancement in the macroarray analysis was also poorer than was the case with > qRT-PCR, because the former method could not detect the EvgA-dependent enhancement of emrKY genes.

TABLE 4.

Fold induction of specific transcripts attributed to evgA amplification as determined by probing of macroarrays and amplification of cDNA samples

| Gene | Fold change bya:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Probing | Amplification | |

| Increased expression | ||

| yfdX | 54 | 1,600 |

| yfdW | 6.8 | 1,300 |

| yfdU | 1.0 | 890 |

| hdeA | 84 | 780 |

| hdeB | 42 | 530 |

| yfdV | 3.0 | 500 |

| yhiE | 6.2 | 400 |

| gadA | 41 | 320 |

| yhiU | 1.8 | 250 |

| yfdE | 4.0 | 170 |

| evgA | 42 | 148 |

| hdeD | 2.7 | 120 |

| yhiV | 4.4 | 67 |

| ypdI | 1.9 | 30 |

| yhiW | 2.8 | 17 |

| emrK | 1.0 | 15 |

| gadX | 3.6 | 13 |

| emrY | 1.1 | 12 |

| tolC | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| hns | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Decreased expression | ||

| fimA | 2.9 | 76 |

| fimI | 3.2 | 40 |

| fimF | 2.8 | 36 |

| fimH | 2.7 | 10 |

| fliA | 2.2 | 5.5 |

| fliC | 2.2 | 4.5 |

Amplification results were obtained by RT of bulk RNA followed by PCR amplification. PCR was performed with each specific primer pair (see Table 2). Probing results were obtained with 33P-labeled cDNA hybridized to DNA macroarrays.

Enhanced expression of genes near evgAS.

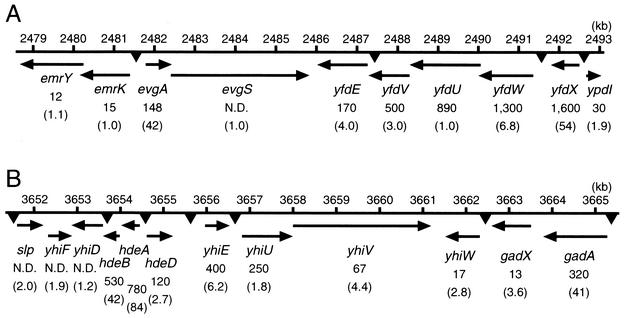

Amplification of the evgA gene elevated the expression of genes located near the evgA gene in the E. coli chromosome (Fig. 1A). That is, two genes (emrKY) upstream and six genes (yfdXWUVE and ypdI) downstream of evgAS were controlled by EvgA. These genes, except for ypdI, are transcribed in the opposite direction from that of evgAS. The emrKY transcript expression was increased as described above. The yfdXWUVE and ypdI transcripts were increased 54-, 6.8-, 1.0-, 3.0-, 4.0-, and 1.9-fold, respectively, in macroarray analysis. qRT-PCR showed increased expression of yfdXWUVE and ypdI by a factor of 1,600, 1,300, 890, 500, 170, and 30, respectively. These values were again larger than the values obtained from the macroarray analysis, while the orders of degree were roughly consistent with each other, except for that of yfdU, which might be due to the inefficient primer for yfdU in the macroarray analysis. It was previously reported that EvgA binds upstream of emrK, and this region contains the inverted repeat sequence TTCTTAC-GTAAGAA (20). By using the SEARCH PATTERN utility (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/Colibri/) we also found that the upstream region of yfdW contains the same sequence (TTCTTAC-GTAAGAA) (Table 5). A similar sequence is also located in the upstream regions of yfdE (TTCTTCA-GTAAGAA), yfdX (TTCTTGC-GTAAGAT), and ypdI (ATCTTAC-GCAAGAA) (Fig. 1A and Table 5). This fact suggests that EvgA may directly regulate yfdE, yfdW, yfdX, and ypdI as well as emrK.

FIG. 1.

Two clusters of EvgA-regulated operons and genes. (A) Gene clusters near the evgAS two-component regulatory system. (B) Gene clusters near the yhiUV multidrug exporter system. Arrows denote the direction of transcription. Putative EvgA-binding motifs are indicated by triangles. Expression changes of genes detected by real-time qRT-PCR are indicated under the gene names. Numbers in parentheses indicate the expression level changes detected by macroarray analyses. Kilobase pairs (kb) indicate the position on E. coli chromosomal DNA as annotated on the Coribri website (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/Colibri/). N.D., not determined.

TABLE 5.

Putative EvgA-binding motifs in EvgA-regulated genes that are located near evgAS or yhiUVa

| Base pairs from start codon | Gene | Pattern sequence |

|---|---|---|

| −172 | gadA | TTATTACGATAATAA |

| −269 | yfdW | TTCTTACAGTTGTAAGAA |

| −563 | yfdE | TTCTTCAGGAGCGGATGGTAAGAA |

| −200 | emrK | TTCTTACTAATCCTACAGGCGTAAGAA |

| −242 | evgA | TTCTTACGCCTGTAGGATTAGTAAGAA |

| −968 | hdeD | TTCTTACAGTATTCGATCACTTTAGGAA |

| −152 | yhiD | TTCCTAAAGTGATCGAATACTGTAAGAA |

| −127 | yfdX | TTCTTGCGATAATAACTACAACTGTAAGAT |

| −564 | yhiU | TACTTATGGTAAACACTTGCCCCATAAGAA |

| −198 | ypdI | ATCTTACAGTTGTAGTTATTATCGCAAGAA |

| −542 | slp | TTCATACAATGACATATTAAAATATCAGCAAGAA |

| −736 | yhiX | CTCTTACCAGGTTGCCGCTTATCTGGCGGATGAA |

| −410 | yhiW | TTTTTACGGCACTGACCGTTCTGCGGAAGGAATAA |

| −279 | hdeA | TTGTTGCCTTATCTATATATAACATAGAACCACCCTATAAAATTAAGAA |

| −99 | yhiE | TTCTTATAGGCGTTTACTATATTGAACAACGATTCGGACAAGGATGTAAATA |

No more than a total of three mismatches were allowed for the entire motif (TTCTTAC-GTAAGAA), and no more than two mismatches were allowed per half. The search was restricted to regions within 1,000 bp upstream of start codons. Putative EvgA-binding motifs are underlined.

Enhanced expression of genes near yhiUV.

Amplification of the evgA gene elevated the expression of genes located near yhiUV in the E. coli chromosome (Fig. 1B). That is, seven genes (hdeABD, slp, and yhiDEF) upstream and three genes (gadAX and yhiW) downstream of yhiUV were controlled by EvgA. Regulation of yhiUV by EvgA was described above. The gadAX, hdeABD, slp, and yhiDEFW transcripts were increased 41-, 3.6-, 84-, 42-, 2.7-, 2.0-, 1.2-, 6.2-, 1.9-, and 2.8-fold, respectively, in macroarray analysis. qRT-PCR showed increased expression of gadAX, hdeABD, and yhiEW by a factor of 320, 13, 480, 530, 120, 400, and 17, respectively. These values were again larger than the values obtained from the macroarray analysis, while the orders of degree were roughly consistent between assays. We searched for a putative EvgA-binding motif in the upstream region of them. As a result, we found the motif in the upstream regions of gadA, hdeA, hdeD, slp, yhiD, yhiW, yhiE, and yhiU (Fig. 1B and Table 5). This fact suggests that these genes may be controlled directly by EvgA. The gadA gene encodes a glutamate decarboxylase (Table 2) (5, 10), and hdeA encodes a chaperone-like protein (13). Both gadA and hdeA play important roles in acid survival. slp encodes a carbon starvation-inducible lipoprotein that stabilizes the outer membrane (2). The functions of hdeD and yhiDWEU are not well understood.

Genes downregulated by EvgA.

Amplification of evgA caused a decrease in expression of 26 genes by a factor of 2 or more (3 genes that were decreased in expression by a factor of 4 or more are listed in Table 2). Of these genes, 12 were involved in metabolism (ansB [factor of 2.9], aspA [3.8], frdA [2.5], garD [2.0], glpQ [4.5], narG [2.7], pflB [2.2], sgaE [2.9], tdcD [2.1], tdcE [2.4], tnaA [7.1], and tnaL [5.0]), and 7 were involved in motility (fimA [factor of 2.9], fimF [2.8], fimH [2.7], fimI [3.2], fliA [2.2], fliC [2.2], and yebV [2.2]). These data suggest that overexpression of evgA may repress the motility of E. coli. We also investigated the expression level changes of fimAFHI and fliAC by qRT-PCR (Table 4). qRT-PCR showed decreased expression of all of these genes, and decreased values were larger than the values obtained from the macroarray analysis, just as in the case of genes whose expression was increased by EvgA.

Effect of EvgA on acid survival.

The list of upregulated genes (Table 2) contains several genes encoding proteins induced at low pH. That is, gadC (formerly called xasA) encodes a probable GABA/glutamate antiporter (11, 16), and gadA and gadB (gadB transcript expression was increased 3.8-fold) encode two glutamate decarboxylases (Table 2) (5, 10). The hdeA-encoded protein has been proposed to have a chaperone-like function under extremely acidic conditions (13). Recently, Hommais et al. reported that gadX (formerly called yhiX; gadX transcript expression was increased 3.6-fold) plays a role in the control of genes induced by low pH (18). This prompted us to study the effect of evgA overexpression on resistance to acidic stress. The overnight (20-h) cultures in LB medium (pH 6.5) were diluted 1:1,000 (dilution to 3 × 106 CFU/ml) into prewarmed LB (pH 2.0). Acid challenge was carried out for 2 h at 37°C. Viable cell counts were determined at 2 h after the acid challenge, and then the percentage of survival was calculated as 100 times the number of CFU per milliliter remaining after acid treatment divided by the initial number of CFU per milliliter at time zero. The normal E. coli cells showed a low level of resistance (0.1% survival) to acid stress. A large increase in resistance (7.9% survival) was measured in evgA-overexpressing cells compared to that measured with the normal cells (a nearly 80-fold increase).

Effect of EvgA on survival under high osmolarity.

Several genes induced by EvgA are involved in the response to high osmolarity. That is, the osmC gene, which is induced by high osmolarity (14), showed an increased mRNA level in the evgA-overexpressing cells. The osmY gene expression is also a locus of hyperosmotic stress response (34). The ompA deletion mutant is significantly more sensitive than that of its parent strain to acidic environment and high osmolarity (47), and the expression of this gene was induced by EvgA overproduction. Nakashima et al. reported that the expression of OmpX is affected by both the medium osmolarity and pressure (29). osmCY and ompAX transcript expressions were increased 2.7-, 3.1-, 2.4-, and 3.1-fold, respectively, in macroarray analysis. We analyzed the role of EvgA in the response to osmotic stress. E. coli cells were grown overnight in LB medium. Cells were diluted 1:1,000 in fresh LB medium supplemented with 3 M NaCl for 1 h at 37°C and then were plated on LB. Viable cells were counted after 16 h at 37°C. A 6.5-fold increase in resistance to high ionic strength was measured in the evgA-overexpressing cells (55.7% survival) compared to that measured in the normal cells (8.7% survival).

Conclusions.

This work investigated the utility of the macroarray analysis in determining the global effects of evgA gene dosage amplification. In this study, we found a lot of genes whose EvgA dependence was not known previously. We discovered that the increased expression of several genes in the EvgA-overexpressing cells resulted in a better ability of cells to survive at low pH and high osmolarity than that of normal cells.

EvgA affects the expression of gene clusters located near emrKY and yhiUV. Since these two clusters contain several EvgA-binding motifs (Fig. 1), most of these are probably controlled directly by EvgA. EmrKY and YhiUV drug exporters need the outer membrane protein TolC for their function, like some other drug transporters of E. coli (16a, 21, 28, 30). Also, EvgA overproduction moderately increased the expression of tolC (Table 4).

Recently it was reported that expression of the gene cluster located near yhiUV is also increased by a deficit of H-NS protein (18). H-NS is a nucleoid-associated protein that is required for the organization of chromosomal DNA (3, 6, 15, 48), and it also functions as a transcription factor (18, 19). We found that there are several overlapping genes whose expression levels were increased both by EvgA overproduction and by the lack of H-NS (indicated in Table 2) (18). Overproduction of EvgA did not change the expression level of hns detected either by macroarray or by qRT-PCR analysis (Table 4), but the expression level of evgA is increased in the H-NS-deficient strain compared to that of its wild-type parent strain (18). This overlap might be due to EvgA overproduction in the H-NS-deficient strain.

Ma et al. reported that the expression of the acrAB multidrug exporter system is induced by treatment with fatty acids, sodium chloride, or ethanol (24). Lomovskaya et al. reported that the emrAB multidrug exporter system is induced by treatment with salicylic acid or 2,4-dinitrophenol (23). It was reported that the expression of yhiUV is controlled by RpoS (4, 43), a conserved alternative sigma factor, that is needed for E. coli to survive stresses associated with starvation, such as heat shock (22, 27), oxidative stress (22, 27), osmotic challenge (27), and near-UV light (42). These events indicate that there is a strong relationship between regulation of drug transporters and stress responses. EvgS may sense some kind of stress. Bock and Gross suggested that EvgS is connected with the oxidation status of the cell via the link to the ubiquinone pool (9). Recently, information about factors that affect the expression of evgAS was obtained from microarray studies. Specifically, it was found that addition of autoinducer 2, a signaling pheromone of quorum sensing, represses the expression of evgS (12) and that the superoxide-generating agent paraquat represses the expression of evgA (37).

Further investigation of the natural signal that activates EvgS is needed in order to understand the biological significance of the EvgS-EvgA signal transduction system and may provide further insights into the role of multidrug transporters in the physiology of the cell.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tomofusa Tsuchiya for strain KAM3. K. Nishino is supported by a research fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alex, L. A., and M. I. Simon. 1994. Protein histidine kinases and signal transduction in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Trends Genet. 10:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, D. M., and A. C. St. John. 1994. Characterization of the carbon starvation-inducible and stationary phase-inducible gene slp encoding an outer membrane lipoprotein in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 11:1059-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali Azam, T., A. Iwata, A. Nishimura, S. Ueda, and A. Ishihama. 1999. Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J. Bacteriol. 181:6361-6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altuvia, S., D. Weinstein-Fischer, A. Zhang, L. Postow, and G. Storz. 1997. A small, stable RNA induced by oxidative stress: role as a pleiotropic regulator and antimutator. Cell 90:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold, C. N., J. McElhanon, A. Lee, R. Leonhart, and D. A. Siegele. 2001. Global analysis of Escherichia coli gene expression during the acetate-induced acid tolerance response. J. Bacteriol. 183:2178-2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atlung, T., and H. Ingmer. 1997. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 24:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbosa, T. M., and S. B. Levy. 2000. Differential expression of over 60 chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of MarA. J. Bacteriol. 182:3467-3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bock, A., and R. Gross. 2002. The unorthodox histidine kinases BvgS and EvgS are responsive to the oxidation status of a quinone electron carrier. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:3479-3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castanie-Cornet, M. P., T. A. Penfound, D. Smith, J. F. Elliott, and J. W. Foster. 1999. Control of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3525-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Biase, D., A. Tramonti, F. Bossa, and P. Visca. 1999. The response to stationary-phase stress conditions in Escherichia coli: role and regulation of the glutamic acid decarboxylase system. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1198-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLisa, M. P., C. F. Wu, L. Wang, J. J. Valdes, and W. E. Bentley. 2001. DNA microarray-based identification of genes controlled by autoinducer 2-stimulated quorum sensing in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5239-5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajiwala, K. S., and S. K. Burley. 2000. HDEA, a periplasmic protein that supports acid resistance in pathogenic enteric bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 295:605-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez, C., and J. C. Devedjian. 1991. Osmotic induction of gene osmC expression in Escherichia coli K12. J. Mol. Biol. 220:959-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayat, M. A., and D. A. Mancarella. 1995. Nucleoid proteins. Micron 26:461-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hersh, B. M., F. T. Farooq, D. N. Barstad, D. L. Blankenhorn, and J. L. Slonczewski. 1996. A glutamate-dependent acid resistance gene in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:3978-3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Hirakawa, H., K. Nisihino, T. Hirata, and A. Yamaguchi. 2003. Comprehensive studies on drug resistance mediated by the overexpression of response regulators of two-component signal transduction systems in Escherichia coli J. Bacteriol. 185:1851-1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoch, J. A., and T. J. Silhavy (ed.). 1995. Two-component signal transduction. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Hommais, F., E. Krin, C. Laurent-Winter, O. Soutourina, A. Malpertuy, J. P. Le Caer, A. Danchin, and P. Bertin. 2001. Large-scale monitoring of pleiotropic regulation of gene expression by the prokaryotic nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 40:20-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacquet, M., R. Cukier-Kahn, J. Pla, and F. Gros. 1971. A thermostable protein factor acting on in vitro DNA transcription. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 45:1597-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato, A., H. Ohnishi, K. Yamamoto, E. Furuta, H. Tanabe, and R. Utsumi. 2000. Transcription of emrKY is regulated by the EvgA-EvgS two-component system in Escherichia coli K-12. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 64:1203-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi, N., K. Nishino, and A. Yamaguchi. 2001. Novel macrolide-specific ABC-type efflux transporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5639-5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange, R., D. Fischer, and R. Hengge-Aronis. 1995. Identification of transcriptional start sites and the role of ppGpp in the expression of rpoS, the structural gene for the sigma S subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:4676-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomovskaya, O., K. Lewis, and A. Matin. 1995. EmrR is a negative regulator of the Escherichia coli multidrug resistance pump EmrAB. J. Bacteriol. 177:2328-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1995. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, N. G. Pon, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6299-6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masaoka, Y., Y. Ueno, Y. Morita, T. Kuroda, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 2000. A two-component multidrug efflux pump, EbrAB, in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:2307-2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCann, M. P., C. D. Fraley, and A. Matin. 1993. The putative sigma factor KatF is regulated posttranscriptionally during carbon starvation. J. Bacteriol. 175:2143-2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagakubo, S., K. Nishino, T. Hirata, and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. The putative response regulator BaeR stimulates multidrug resistance of Escherichia coli via a novel multidrug exporter system, MdtABC. J. Bacteriol. 184:4161-4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakashima, K., K. Horikoshi, and T. Mizuno. 1995. Effect of hydrostatic pressure on the synthesis of outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 59:130-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikaido, H. 1996. Multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:5853-5859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2001. Analysis of a complete library of putative drug transporter genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5803-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. EvgA of the two-component signal transduction system modulates production of the yhiUV multidrug transporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:2319-2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishino, K., and A. Yamaguchi. 2001. Overexpression of the response regulator evgA of the two-component signal transduction system modulates multidrug resistance conferred by multidrug resistance transporters. J. Bacteriol. 183:1455-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh, J. T., T. K. Van Dyk, Y. Cajal, P. S. Dhurjati, M. Sasser, and M. K. Jain. 1998. Osmotic stress in viable Escherichia coli as the basis for the antibiotic response by polymyxin B. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 246:619-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parkinson, J. S. 1993. Signal transduction schemes of bacteria. Cell 73:857-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parkinson, J. S., and E. C. Kofoid. 1992. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 26:71-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pomposiello, P. J., M. H. Bennik, and B. Demple. 2001. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J. Bacteriol. 183:3890-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley, M., and B. Labedan. 1996. Escherichia coli gene products: physiological functions and common ancestries, p. 2118-2202. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Renznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D. C.

- 39.Riley, M., and B. Labedan. 1997. Protein evolution viewed through Escherichia coli protein sequences: introducing the notion of a structural segment of homology, the module. J. Mol. Biol. 268:857-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudd, K. E. 2000. EcoGene: a genome sequence database for Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:60-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 42.Sammartano, L. J., R. W. Tuveson, and R. Davenport. 1986. Control of sensitivity to inactivation by H2O2 and broad-spectrum near-UV radiation by the Escherichia coli katF locus. J. Bacteriol. 168:13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schellhorn, H. E., J. P. Audia, L. I. Wei, and L. Chang. 1998. Identification of conserved, RpoS-dependent stationary-phase genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:6283-6291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, J. A. Giron, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. Quorum sensing is a global regulatory mechanism in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 183:5187-5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swanson, R. V., L. A. Alex, and M. I. Simon. 1994. Histidine and aspartate phosphorylation: two-component systems and the limits of homology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tao, H., C. Bausch, C. Richmond, F. R. Blattner, and T. Conway. 1999. Functional genomics: expression analysis of Escherichia coli growing on minimal and rich media. J. Bacteriol. 181:6425-6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, Y. 2002. The function of OmpA in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292:396-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams, R. M., and S. Rimsky. 1997. Molecular aspects of the E. coli nucleoid protein, H-NS: a central controller of gene regulatory networks. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]