Abstract

Pseudomonas syringae is a plant pathogen whose pathogenicity and host specificity are thought to be determined by Hop/Avr effector proteins injected into plant cells by a type III secretion system. P. syringae pv. syringae B728a, which causes brown spot of bean, is a particularly well-studied strain. The type III secretion system in P. syringae is encoded by hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) and hrc (hrp conserved) genes, which are clustered in a pathogenicity island with a tripartite structure such that the hrp/hrc genes are flanked by a conserved effector locus and an exchangeable effector locus (EEL). The EELs of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a, P. syringae strain 61, and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 differ in size and effector gene composition; the EEL of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a is the largest and most complex. The three putative effector proteins encoded by the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL—HopPsyC, HopPsyE, and HopPsyV—were demonstrated to be secreted in an Hrp-dependent manner in culture. Heterologous expression of hopPsyC, hopPsyE, and hopPsyV in P. syringae pv. tabaci induced the hypersensitive response in tobacco leaves, demonstrating avirulence activity in a nonhost plant. Deletion of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL strongly reduced virulence in host bean leaves. EELs from nine additional strains representing nine P. syringae pathovars were isolated and sequenced. Homologs of avrPphE (e.g., hopPsyE) and hopPsyA were particularly common. Comparative analyses of these effector genes and hrpK (which flanks the EEL) suggest that the EEL effector genes were acquired by horizontal transfer after the acquisition of the hrp/hrc gene cluster but before the divergence of modern pathovars and that some EELs underwent transpositions yielding effector exchanges or point mutations producing effector pseudogenes after their acquisition.

The plant-pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae uses the Hrp (type III protein secretion) system to deliver effector proteins into plant cells to promote its growth (19). The Hrp system is encoded by hrp/hrc genes, which are so named because they are required for P. syringae strains to cause the hypersensitive response (HR) in nonhost plants and pathogenesis in hosts and because a subset of these genes (hrp conserved) are core components of the type III secretion systems of plant and animal pathogens (10). The Hrp system is essential to the virulence of most gram-negative plant pathogens, but the function of effector proteins in bacterial pathogenesis is not well understood. These proteins were originally identified in P. syringae because they induce the defense-associated HR in plants carrying cognate R genes and consequently are commonly referred to as Avr (avirulence) proteins (22). P. syringae is a host-specific pathogen, and a key factor in the assignment of a strain to one of at least 50 pathovars is its compatibility (ability to grow and cause disease) in some plant species and incompatibility (elicitation of the HR) in other plants. Hrp effectors appear to be key factors controlling this host specificity.

A handful of effector proteins have also been shown to make a detectable contribution to virulence in compatible interactions. For example, AvrRpm1 and AvrRpt2 are able to increase pathogen growth in Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes that do not carry corresponding R genes (7, 14, 35). A deletion of avrPphF in P. syringae pv. phaseolicola leads to the loss of virulence to a range of susceptible bean cultivars (44). Heterologous expression of AvrPto in P. syringae pv. tomato T1 produces an increase in bacterial growth in tomato lacking the pathovar tomato resistance gene (39). Interestingly, the virulence function of effector proteins appears to be context dependent: the phenotype varies depending on the virulence assay, other effectors produced by the strain, and the combinations of bacterial strains and susceptible host plants tested. These observations are consistent with the concept that effectors are horizontally acquired, vary among strains, and may function both redundantly and interdependently.

P. syringae pv. syringae B728a is typical of the species. It is a foliar pathogen and causes bacterial brown spot disease on snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). It is also a common inhabitant of leaf surfaces, on which it can multiply well under adverse environmental conditions, and the buildup of a threshold epiphytic population often precedes disease development in the field (26). The association of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a with leaves thus has two phases, epiphytic and endophytic, and this strain has become a model for investigating the basis for bacterial epiphytic growth and field fitness (18). The Hrp system is one factor contributing to the field fitness of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a on bean plants, as indicated by the reduced population size of hrp/hrc mutants relative to that of the wild type following inoculation onto seeds at the time of planting (17).

In P. syringae, the hrp genes are located on the chromosome in a pathogenicity island with a tripartite structure composed of an exchangeable effector locus (EEL), a cluster of hrp/hrc type III secretion genes, and a conserved effector locus (CEL) (2). The CEL carries several candidate effector genes, and a large deletion in the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 CEL abolishes pathogenicity (2), which suggests that the CEL might be one of several necessary contributors to pathogenesis. In contrast, the region residing between hrpK and tRNALeu of the Hrp pathogenicity island was given the EEL designation because it contains completely different candidate effector genes in the different strains that were initially investigated (2). Furthermore, the EELs are rich in transposable elements and plasmid-related sequences, and the G+C content of the open reading frames (ORFs) in the EELs is significantly lower than the genomic average of 59% for P. syringae (calculated from the whole genome of pathovar tomato DC3000), which is a hallmark of horizontally transferred genes.

The ORFs in the pathovar tomato DC3000 EEL predict products with no similarity to any known effector proteins; however, deletion of the EEL in pathovar tomato DC3000 partially reduces pathogen fitness in planta, indicating that the ORFs might collectively contribute to parasitism. The strain 61 EEL (2.5 kb) has two ORFs: HopPsyA is an effector protein that has avirulence activity when it is heterologously expressed in P. syringae pv. tabaci cells that are subsequently infiltrated into tobacco leaves (4), and shcA encodes a chaperone that is required for the secretion of HopPsyA (45, 46). The 7.3-kb EEL of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a encodes three putative effector proteins that are homologous to AvrB and AvrC of P. syringae pv. glycinea, AvrPphE of P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1302A, and AvrRxv of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, respectively (2). The role of AvrB, AvrC, AvrPphE, and AvrRxv in incompatible interactions has been established (8, 41, 43); however, no role in virulence has been demonstrated.

The objectives of this study were (i) to determine if the ORFs in the complex EEL of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a encode proteins that travel the Hrp pathway, have Avr activity, and collectively contribute to virulence and (ii) to explore the range of effector variability in EELs from a larger set of P. syringae pathovars. To achieve the first goal, we assessed the virulence function of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL through construction of a deletion mutation and we also tested the avirulence activity and Hrp-dependent secretion of the putative effector proteins. To achieve the second goal, we amplified and sequenced the EEL regions from several other P. syringae pathovars. Our results reveal that (i) the effector proteins encoded by the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL are secreted into the bacterial milieu in an Hrp-dependent manner, (ii) heterologous expression of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL effector genes in P. syringae pv. tabaci confers an avirulence phenotype, (iii) deletion of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL strongly reduces virulence, and (iv) the sequence of a larger set of EELs from different pathovars reveals both recurring features and additional variations in EEL structure. Based on the secretion results, we renamed three of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL ORFs HopPsyC, HopPsyE, and HopPsyV (Hrp-dependent outer proteins of P. syringae) following recommendations for uniform designation of P. syringae effectors (3, 47), and we have chosen last-letter designations that evoke founding members of the respective effector families (AvrC, AvrPphE, and AvrRxv).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains of Escherichia coli and P. syringae were grown routinely on modified Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C and King's medium B (KB) at 28°C, respectively (24, 30). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (milligrams per liter): rifampin, 50; tetracycline, 10; kanamycin, 50; ampicillin, 100; spectinomycin, 50; gentamicin, 10; and cycloheximide, 2. Cloning and DNA manipulations were done in E. coli DH5α with vectors pBluescript II (Stratagene), pFLAG-CTC (Sigma), pRK415 (23), pCPP46, and pUCP24 (48), according to standard procedures (37). Plasmids were transformed into P. syringae by triparental mating or electroporation under described conditions (6). The Erwinia chrysanthemi type III system, pCPP3042, is a derivative of pCPP2156 (15) that has been improved by the deletion of extraneous sequences flanking the functional hrp/hrc gene cluster; pCPP3127 is an hrcT mutant derivative of pCPP3042 that has an insertion of interposon (ΩSpr) in hrcT, which is impaired in type III-dependent secretion.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5αF′ | F−/endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA1 Δ(laclZYA-argF)U169 deoR (φ80dlac Δ[lacZ]M15) | Life Sciences Technologies |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL(Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| P. syringae pv. syringae 61 | Wild type isolated from wheat, Nalr | 20 |

| pv. syringae 226 | Wild type, Nalr | T. Denny |

| pv. syringae B728a | Wild type, Rifr | 50 |

| pv. tabaci 11528 | Wild type, Rifr | American Type Culture Collection |

| pv. angulata Pa9 | Wild type | D. K. Willis |

| pv. atrofaciens B143 | Wild type | T. Denny |

| pv. delphinii PDDCC 529 | Wild type | T. Denny |

| pv. glycinea race 4 | Wild type | C. J. Baker |

| pv. morsprunorum PDDCC 5795 | Wild type | T. Denny |

| pv. mori PDDCC 4331 | Wild type | T. Denny |

| pv. phaseolicola B130 | Wild type | T. Denny |

| pv. tomato DC3000 | Wild type, Rifr | D. Cuppels |

| CUCPB5102 | B728a ΔhrcC::nptll, HR−, Rifr Kanr | 17 |

| CUCPB5111 | B728a ΔEEL::ΩSpr, HR+, Rifr Sptr | This work |

| pBluescript KS or SK | ColE1, Apr, MCS-lacZa | Stratagene |

| pCR-XL-TOPO | ColE1, MCS-lacZccdB, Kmr, Zeocinr | Invitrogen |

| pUCP24 | ColE1, ori1600, MCS-lacZ, Gmr | 48 |

| pFLAG-CTC | For construction of C-terminal fusion to FLAG peptide, Apr | Sigma |

| pRK415 | Broad-host-range vector unstable in absence of selection, Tcr | 23 |

| pRK2013 | IncP Tra RK2+ ΔrepE1+ Kmr | 12 |

| pCPP46 | IncP LacZ′ Par+; Tcr | D. W. Bauer |

| pCPP3042 | pCPP46 carrying the E. chrysanthemi AC4150 hrp/hrc genes, Tcr | This work |

| pCPP3127 | pCPP3042 with a mutation in hrcT (hrcT::ΩSpr), Tcr Spr | This work |

| pCPP3092 | pCPP46 carrying the P. syringae B728a hrpK and EEL, Tcr | This work |

| pCPP3105 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar tabaci EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3106 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar glycinea EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3107 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar angulata EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3108 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar phaseolicola EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3109 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar syringae 226 EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3110 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar tomato DC3000 EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3111 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar syringae B728a EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3113 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar morsprunorum EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3115 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar delphinii EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3116 | pCR-XL-TOPO::pathovar atrofaciens EEL, Kmr, Zeocinr | This work |

| pCPP3117 | pFLAG-CTC::hopPsyC, Apr | This work |

| pCPP3118 | pFLAG-CTC::ORF6-hopPsyV, Apr | This work |

| pCPP3119 | pFLAG-CTC::hopPsyE, Apr | This work |

| pCPP3153 | pUCP24::hopPsyC-FLAG, Gmr | This work |

| pCPP3154 | pUCP24::hopPsyE-FLAG, Gmr | This work |

| pCPP3155 | pUCP24::ORF6-hopPsyV-FLAG, Gmr | This work |

MCS, multiple cloning site.

Protein analysis.

For immunoblot analysis, bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani broth at 28°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.35, and 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added into the culture to induce the expression of HopPsyC-FLAG, HopPsyE-FLAG, and HopPsyV-FLAG. The induced cultures were harvested at an OD600 of 0.7 and were separated into cell-bound and supernatant fractions by centrifugation. The proteins in the supernatant fractions were concentrated 300× by trichloroacetic acid precipitation. Proteins were resolved in a sodium dodecyl sulfate-12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel, transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore) with a Semi-Phor system (Hoefer), immunostained with antibodies against FLAG monoclonal antibody and β-galactosidase (Sigma), and visualized by chemiluminescence (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.) as described earlier (15).

Mutant construction and analysis.

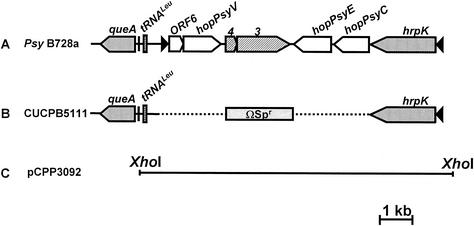

Constructions of mutation and complementing clone are illustrated in Fig. 1. Deletion of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL was done by subcloning border fragments into restriction sites on either side of an ΩSpr cassette in pRK415, conjugating the recombinant plasmid into P. syringae pv. syringae B728a, and then selecting and screening for marker exchanged mutants as described (1). The left and right deletion border fragments used (with residual gene fragments indicated) for making CUCPB5111 were tgt-queA-tRNALeu-intA′ (117 bp upstream of the ORF6 start codon) and hopPsyC′-hrpK (312 bp of hopPsyC), respectively, which result in a 5,924-bp deletion of hopPsyC to ORF6. Mutant construction was confirmed by Southern hybridization under previously described conditions (6). Complementation was done by subcloning a 10,488-bp XhoI fragment into pCPP46, resulting in pCPP3092, and conjugating the plasmid into CUCPB5111 by triparental mating (20). pCPP46 and derivatives carry a par locus and were confirmed to be stable in P. syringae in planta without antibiotic selection.

FIG. 1.

Construction of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL deletion mutation and its corresponding complementation clone. (A) Physical map of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL. Pointed boxes indicate the predicted ORFs and the direction of transcription, with black triangles representing the presence of an Hrp box promoter. Hatched regions represent mobile genetic elements, and open boxes are putative effector or chaperone genes. (B) EEL deletion mutant CUCPB5111, with the dotted line representing the internal deletion that is replaced by an ΩSpr cassette. (C) The 10,488-bp XhoI fragment shown contains hrpK to tRNALeu in pCPP3092.

Plant bioassays.

HR assays were performed in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Xanthii) plants that were grown under greenhouse conditions at 23 to 25°C with a photoperiod of 16 h and were transferred to the laboratory for assays. Snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv. Eagle) was grown at 22°C in a growth chamber with a photoperiod of 12 h for pathogenicity assays. Bacteria were grown overnight on KB agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics, suspended in distilled water to an OD600 of 0.3 (equivalent to 5 × 108 CFU ml−1), and then infiltrated with a blunt syringe into the leaves of test plants for HR assays. For pathogenicity assays, the bacteria were suspended in distilled water at a density of 104 (for syringe infiltration) or 105 CFU ml−1 (for dipping inoculation). Plants were incubated in the growth chamber at high humidity, and leaf disks were sampled 0 and 3 days postinoculation. Disks were collected in a microcentrifuge tube containing 500 μl of distilled water and were homogenized with a plastic pestle, and the homogenates were plated in a dilution series on KB agar plates supplemented with rifampin and cycloheximide to determine bacterial population.

Isolation and cloning of the EELs from different pathovars of P. syringae.

Chromosomal DNA from different P. syringae pathovars was prepared as previously described (37) and was used as templates for isolation of the EELs by PCR. Primers used for PCR amplification, as shown in Table 2, were designed from the conserved sequences of hrpK and tRNALeu or queA. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Genosys, Fisher Scientific or Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa). PCR was performed with 1× PCR buffer, 100 ng of DNA templates, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphate, a 0.8 μM concentration of each primer, and 2 U of Taq Plus long polymerase (Stratagene) per 50-μl reaction, in an Eppendorf Mastercycler gradient thermal cycler (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, N.Y.) following the listed program: 90°C, 1 min for denaturation; 90°C, 30 s; 55 ± 10°C, 45 s; 72°C, 9 min, 30 cycles for amplification; and 72°C, 10 min for extension. The PCR-amplified DNA fragments were gel purified with the Prep-A-Gene DNA purification system (Bio-Rad) and were cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO vector by the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). All DNA sequencing was done at the Cornell Biotechnology Center with an automated DNA sequencer, model 373A (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| P577 | 5′-GCAACGGCAGCACTTCTTCGGCAAA | queA |

| P578 | 5′-AGGGTCAACAGACGACTGCTGCGACG | queA |

| P579 | 5′-GGCATAGACACCGGCGCGAAAATGA | hrpK |

| P580 | 5′-GCCTAGGGCGTCTGGGCGGACAG | hrpK |

| P602 | 5′-GGTCGTCTGGGCGGACAGATGATCG | hrpK |

| P706 | 5′-TGGTAGACGCGGCGGATTCAAA | tRNALeu |

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis.

Raw sequence data were analyzed by using DNAStar version 4.05, and sequence alignments were facilitated by using the CLUSTAL W method in the MegAlign program and optimized manually. The entire avrPphE coding region (bp 1143 to 1155) and 250-bp hrpK (corresponding to positions 2067 to 2316 of the strain 61 hrpK gene) sequences were used in the alignments. Phylogenetic analysis was performed on an Apple Power Macintosh G4 by using maximum unweighted parsimony as an optimality criterion implemented in the computer program PAUP* 4.0b8 (42). Gaps were treated as missing data. A heuristic search with 100 random-addition sequence replicates was performed by using stepwise addition to ensure finding the most parsimonious tree, followed by a bootstrap analysis with 100 resamplings to confirm the probability of branching orders.

RESULTS

The P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL encodes three putative effector proteins that share homology with known effectors and are secreted in culture by the E. chrysanthemi Hrp type III secretion system.

The structure of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL has been reported elsewhere (2). Three of the ORFs in this region appear to encode effectors. ORF1 (HopPsyC) encodes a protein with an estimated molecular mass of 36.6 kDa, and it is homologous to pathovar phaseolicola AvrPphC and pathovar glycinea AvrB and AvrC, with 30 to 34% identity in amino acid sequence. ORF2 (HopPsyE) is a homolog of pathovar phaseolicola AvrPphE, with 77% identity and 83% similarity, and it has an estimated molecular mass of 40.8 kDa. ORF5 (HopPsyV) predicts a 45.7-kDa protein with multiple motifs characteristic of the AvrRxv family (8). The P. syringae pv. syringae B728a HopPsyV and Erwinia amylovora AvrRxv homolog, ORFB (GenBank accession number AF083620 [Kim et al. unpublished]), share 53% identity, and they are both structurally linked to their respective hrp/hrc clusters. The small ORF preceding hopPsyV shows no homology to other sequences deposited in GenBank. Although the function of this ORF has not been characterized, it shares general characteristics with chaperones used in the type III secretion system of animal pathogens and ShcA of strain 61 (46), and we predict that it is a chaperone assisting secretion of the effector encoded in the same operon.

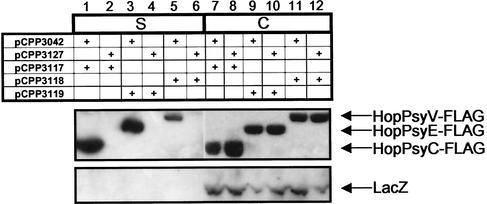

The three genes postulated to encode Hops were cloned into a pFLAG-CTC vector, resulting in pCPP3117 (HopPsyC-FLAG), pCPP3119 (HopPsyE-FLAG), and pCPP3118 (HopPsyV-FLAG). These constructs were transformed into E. coli carrying pCPP3042 (functional E. chrysanthemi hrp/hrc gene cluster) or pCPP3127 (mutant E. chrysanthemi hrp/hrc gene cluster) for secretion assays. HopPsyC-FLAG, HopPsyE-FLAG, and HopPsyV-FLAG were visualized by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody and chemiluminescent detection. All three FLAG epitope-tagged proteins were found in the supernatant fractions of E. coli(pCPP3042) but not in those of E. coli(pCPP3127), indicating that all three proteins are secreted in an Hrp-dependent manner (Fig. 2, upper panel). To confirm that the presence of HopPsyC-FLAG, HopPsyE-FLAG, and HopPsyV-FLAG in the E. coli(pCPP3042) milieu resulted from specific secretion and not cell lysis, we simultaneously monitored the localization of tagged proteins and β-galactosidase, a 116-kDa cytoplasmic protein encoded by the native E. coli lacZ gene. E. coli(pCPP3042) supernatant fractions contained no β-galactosidase (Fig. 2, bottom panel). Furthermore, Coomassie staining of polyacrylamide gels revealed no evidence of cytoplasmic proteins in the supernatant fractions of either E. coli(pCPP3042) or E. coli(pCPP3127) (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of HopPsyC-FLAG, HopPsyE-FLAG, and HopPsyV-FLAG secretion by E. coli carrying an intact (pCPP3042) or defective (pCPP3127) E. chrysanthemi type III secretion system. The supernatant fraction (S) was concentrated 7.5 times more than the cell-bound fraction (C). The upper panel was immunostained with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody, and the bottom panel was stained with anti-β-galactosidase serum.

hopPsyC, hopPsyE, and hopPsyV convert P. syringae pv. tabaci to incompatibility in tobacco.

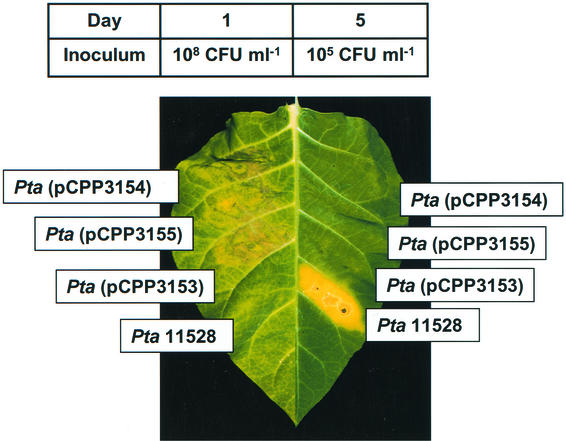

We next determined if hopPsyC, hopPsyE, or hopPsyV had avirulence activity in tobacco, as would be indicated if the transfer of these genes into a tobacco pathogen resulted in incompatibility. Pathovar tabaci 11528 causes wildfire disease of tobacco and was used in this test. We constructed pCPP3092 (which carries the entire P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL in broad-host-range vector pCPP46) and plasmids pCPP3153, pCPP3154, and pCPP3155 (which carry hopPsyC-FLAG, hopPsyE-FLAG, and hopPsyV-FLAG, respectively, in broad-host-range vector pUCP24), and we electroporated each plasmid into pathovar tabaci. Pathovar tabaci(pCPP3153), pathovar tabaci(pCPP3154), pathovar tabaci(pCPP3155), and wild-type pathovar tabaci 11528 were infiltrated into tobacco (N. tabacum L. Xanthii) leaves at two different concentrations—108 and 105 CFU ml−1—and the phenotype was scored 1 and 5 days after infiltration. Leaf panels infiltrated with pathovar tabaci(pCPP3153), pathovar tabaci(pCPP3154), and pathovar tabaci(pCPP3155) at 108 CFU ml−1 displayed a typical hypersensitive collapse within 24 h (Fig. 3, leaf on the left), whereas those infiltrated with the lower concentration of bacteria failed to produce disease symptoms 5 days after inoculation (Fig. 3, leaf on the right). As expected, pathovar tabaci(pCPP3092) had the same avirulence phenotype as pathovar tabaci strains expressing individual EEL effectors (data not shown). In contrast, pathovar tabaci 11528 elicited no visible response 24 h after infiltration but produced disease symptoms within 5 days (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the growth of pathovar tabaci was substantially higher than that of pathovar tabaci(pCPP3153), pathovar tabaci(pCPP3154), and pathovar tabaci(pCPP3155) at the lower inoculum level (data not shown). The same approach was used to test the reactions of hopPsyC+, hopPsyE+, and hopPsyV+ bacteria with other Nicotiana spp., and plant reactions were scored 5 days after infiltration. Nicotiana clevelandii and Nicotiana benthamiana both produced disease symptoms, rather than the HR, when inoculated with pathovar tabaci, regardless of the presence of hopPsyC, hopPsyE, or hopPsyV. Thus, hopPsyC, hopPsyE, and hopPsyV confer an avirulence phenotype to pathovar tabaci in N. tabacum cv. Xanthii but not in the other Nicotiana spp. that were tested.

FIG. 3.

Hypersensitive response of tobacco leaves to infiltration with P. syringae pv. tabaci 11528 transformants expressing Hops encoded by the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL. Leaves were inoculated with P. syringae pv. tabaci 11528 harboring pCPP3153 (hopPsyC+), pCPP3154 (hopPsyE+), or pCPP3155 (hopPsyV+). The leaf on the left was infiltrated with 108 CFU ml of inoculum−1, and the one on the right was infiltrated with 105 CFU ml−1. Photographs were taken 1 and 5 days postinfiltration, respectively.

Deletion of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL reduces HR elicitation in nonhost tobacco and pathogen growth in host bean.

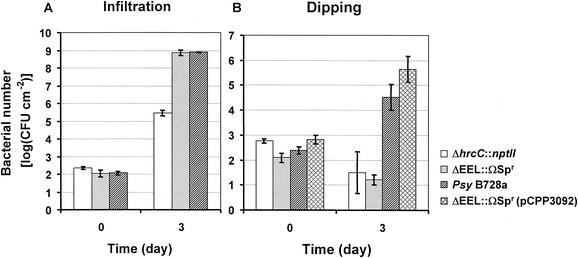

To determine if the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL contributes to the interactions of the bacterium with host and nonhost plants, a mutation was constructed in P. syringae pv. syringae B728a, which replaced all of the ORFs between hrpK and tRNALeu with an ΩSpr cassette (Fig. 1B). This P. syringae mutant, CUCPB5111, was tested for its ability to elicit the HR in tobacco and to cause disease in bean. The mutant retained its ability to elicit the HR in tobacco when it was introduced into the intercellular space of a leaf by syringe infiltration at 108 CFU ml−1. However, in contrast to the wild type, the mutant exhibited no macroscopic necrosis in tobacco when it was infiltrated at 106 CFU ml−1, although the wild-type phenotype could be restored by complementation with pCPP3092 (data not shown). The mutant was also able to produce disease symptoms in bean when it was introduced by syringe infiltration at 104 CFU ml−1. Interestingly, when we changed the inoculation method to dipping, the mutant exhibited reduced growth 3 days postinoculation compared with the wild type (Fig. 4). In addition, the mutant produced delayed and smaller lesions. Plasmid pCPP3092, which carries hrpK through ORF6 (Fig. 1C), restored the growth of CUCPB5111 (Fig. 4) and symptom production (data not shown), indicating that the impaired growth ability of CUCPB5111 is due to the deletion of the EEL.

FIG. 4.

Growth of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a, its mutant derivatives CUCPB5102 (ΔhrcC::nptII) and CUCPB5111 (ΔEEL::ΩSpr), and complemented strain CUCPB5111(pCPP3092) in bean leaves. Bacteria were inoculated by (A) infiltration with 104 CFU ml−1 or (B) dipping with 105 CFU ml of inoculum−1. Each point represents the mean and standard error of three samples, and each sample is composed of 10 7-mm leaf disks.

Heterologous expression of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL in a weak pathogen of bean, P. syringae pv. syringae strain 61, does not enhance strain 61 growth.

We next asked if the differing EELs of two strains in the same pathovar could account for their differing abilities to grow in bean leaves. P. syringae pv. syringae strain 61 is a weak pathogen of bean that does not grow in bean nearly as well as P. syringae pv. syringae B728a. Strain 61 was first isolated as an epiphyte from wheat and later found to be weakly pathogenic on bean. The hrp/hrc cluster of strain 61, cloned on cosmid pHIR11, has been studied most extensively because it encodes a functional type III secretion system and HopPsyA, which enables nonpathogenic bacteria, such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and E. coli, to elicit the HR in tobacco and several other plants (20). Both highly virulent strain B728a and weakly virulent strain 61 are in the same pathovar, and they share 95.4% nucleotide identity in the 2,935-bp region containing hrpL to hrpK. However, the gene compositions of their EELs are totally different. To learn if the presence of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL sequences could enhance growth of strain 61 in planta, plasmid pCPP3092, which carries the strain B728a EEL, was conjugated into strain 61. The transconjugant was inoculated onto bean leaves by infiltration or dipping, and the plants were kept in a growth chamber at 22°C with high humidity for 5 days. No difference in bacterial growth and symptom development was observed between strain 61, strain 61(pCPP3092), and strain 61(pCPP46) (empty vector control) (data not shown). Thus, although pCPP3092 could restore growth and virulence phenotypes to the strain B728a EEL deletion mutant CUCPB5111 and confer an avirulence phenotype to pathovar tabaci in N. tabacum cv. Xanthii, it was inadequate to enhance the growth of strain 61 in bean.

The sequences of multiple P. syringae EELs reveal both recurring features and new variations.

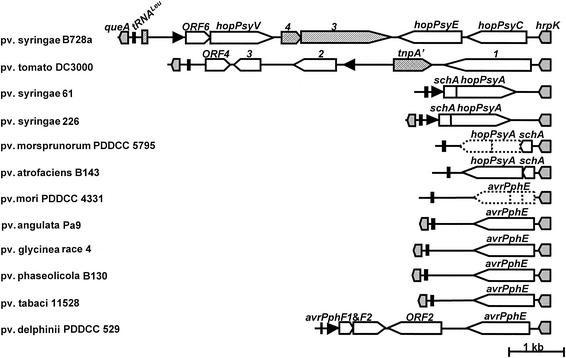

By using primers designed from the conserved flanking regions of the EEL, we were able to amplify the loci from several P. syringae pathovars: tomato DC3000, syringae strains B728a and 226, morsprunorum PDDCC 5795, atrofaciens B143, mori PDDCC 4331, angulata Pa9, glycinea race 4, phaseolicola B130, tabaci 11528, and delphinii PDDCC 529. These strains were chosen to represent taxonomically diverse pathovars and hosts. We included pathovars tomato DC3000 and syringae B728a to confirm that the primers and PCR protocols worked properly. The physical maps and detailed information on the EELs from different pathovars are given in Fig. 5 and Table 3. Surprisingly, the candidate effectors in this new set of EELs were similar to previously identified P. syringae effectors (2). Six of the EELs investigated (pathovars angulata, delphinii, syringae B728a, phaseolicola B130, tabaci, and glycinea) have AvrPphE homologs residing between hrpK and tRNALeu, as do two sequences that have been published elsewhere (pathovar tabaci 11528 [41] and pathovar phaseolicola 1302A [29]). The nucleotide sequence of the pathovar mori EEL is highly similar to that of pathovar phaseolica B130; however, there was a nonsense mutation at position 118 (G→T) and a 10-bp insertion between positions 435 and 436 of the AvrPphE-coding region in pathovar mori, which result in a truncated ORF of 120 bp in length. The predicted ORFs in the EELs of pathovar atrofaciens and pathovar syringae 226 encode two proteins similar to ShcA and HopPsyA of the pathovar syringae 61 EEL with 31 and 89% amino acid sequence identities, respectively. The EELs of pathovar morsprunorum and pathovar atrofaciens have 95% nucleotide identity; however, the coding region of the second ORF in the pathovar morsprunorum 5795 EEL is disrupted by a nonsense mutation at position 493 (G→T) (Table 3), resulting in an ORF with 164 amino acids. It is also noteworthy that the gene organization in the EELs of pathovars atrofaciens and morsprunorum is different from that of pathovar syringae strains 61 and 226, as shown in Fig. 5. The former pair has shcA-hopPsyA transcriptionally fused with hrpK, which contrasts with the independent transcriptional unit of the latter ones, which are transcribed opposite to the hrpK operon. In fact, in all the sequenced EELs, the predicted ORF that is immediately downstream of hrpK appears to be in the same transcription unit with hrpK, except for the EELs isolated from pathovar syringae strains 61 and 226 (Fig. 5). In addition to avrPphE, the pathovar delphinii EEL predicts three additional ORFs that share homology with candidate effectors: ORF2 of the pathovar tomato DC3000 EEL (2) and avrPphF1 and avrPphF2 of pathovar phaseolicola strains 1375A and 1449B (44). The percent identity of deduced amino acid sequences to known effector proteins is listed in Table 3.

FIG. 5.

Physical maps of the EELs of P. syringae pv. syringae B728a and other strains. Pointed boxes indicate the predicted ORFs and the direction of transcription, black triangles indicate the presence of the Hrp box, and black boxes indicate the position of tRNALeu. Stippled regions are conserved among different pathovars and were used for primer design. Hatched regions represent mobile genetic elements. Open boxes with solid lines are putative effector genes, whereas boxes with dotted lines are apparent pseudogenes.

TABLE 3.

P. syringae strains and primers used to isolate the EELs by PCR

| P. syringae pathovar or strain | Primers | Plasmid | Amplified fragment length (bp) | Encoded proteins and homologsa (% identity) | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pv. mori PDDCC 4331 | P580, P706 | pCPP3114 | 2,249 | AvrPphEb | AF461553 |

| pv. angulata Pa9 | P602, P577 | pCPP3107 | 2,731 | AvrPphE (97.9)d | AF461554 |

| pv. atrofaciens B143 | P580, P706 | 2,275 | ShcA (55)c; HopPsyA (31)c | AF461555 | |

| pv. delphinii PDDCC 529 | P580, P706 | pCPP3115 | 4,599 | AvrPphE (73.4)d; ORF2 (86)i; AvrPphF1 (50)e; AvrPphF2 (52)f | AF461556 |

| pv. glycinea race 4 | P579, P577 | pCPP3106 | 2,878 | AvrPphE (99.5)d | AF461557 |

| pv. morsprunorum PDDCC 5795 | P580, P706 | pCPP3113 | 2,277 | ShcA (56)c; HopPsyAb | AF461558 |

| pv. phaseolicola B130 | P579, P578 | pCPP3108 | 2,561 | AvrPphE (100)d | AF461559 |

| pv. syringae 226 | P579, P578 | pCPP3109 | 3,100 | ShcA (100)c; HopPsyA (88.6)c | AF461561 |

| pv. syringae B728a | P579, P577 | pCPP3111 | 8,286 | HopPsyC (38)g; HopPsyE (77.1)d; HopPsyV (21)h | AF232005 |

| pv. tabaci 11528 | P579, P577 | pCPP3105 | 2,782 | AvrPphE (98.9)d | AF461560 |

| pv. tomato DC3000 | P602, P577 | pCPP3110 | 6,816 | ORF1; ORF2; ORF3; ORF4 | AF232004 |

GenBank accession numbers of homologous proteins are given below.

The predicted ORF is smaller than published sequences due to nonsense mutations in the coding region.

Strain 61 ORF1 and HopPsyA, AF232003.

pv. phaseolicola 1302A AvrPphE, U16817.

pv. phaseolicola AvrPphF1, AAF67151.

pv. phaseolicola AvrPphF2, AAF67152.

pv. phaseolicola AvrPphC, AAA83419.

pv. versicatoria AvrBs T, AF156163.

pv. tomato DC3000 ORF2, AF232004.

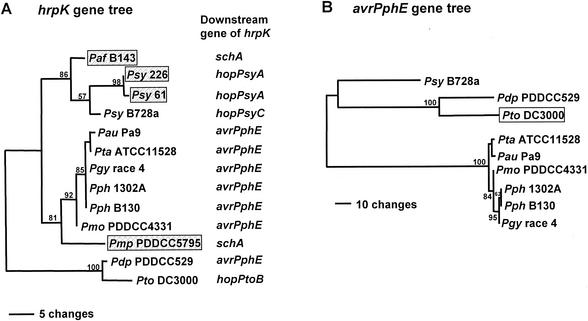

Phylogenetic analyses of avrPphE and hrpK.

The presence of avrPphE homologs in the EELs of most of the P. syringae pathovars that we investigated prompted us to phylogenetically compare this effector gene and hrpK. After exclusion of noninformative characters, a heuristic search yielded two equally parsimonious trees for the avrPphE data with 620 steps, a consistency index of 0.872, and a retention index of 0.869. The topologies of the trees differed only within the clade containing pathovars mori, phaseolicola, glycinea, tabaci, and angulata (the latter two pathovars are virtually synonymous) (Fig. 6B). The hrpK gene tree, depicted in Fig. 6A, was generated by the same method with 63 steps, a consistency index of 0.794, and retention index of 0.874. The bootstrap probabilities, determined by 100 resamplings, are indicated near the clade where applicable (Fig. 6). Phylogenetic analyses using hrpL, hrpS, rpoD, and gyrB as index genes have revealed that 19 P. syringae pathovars can be divided into three distinct monophyletic groups (38). The avrPphE and hrpK gene trees constructed in this study are consistent with this and clearly distinguished the group of pathovar tabaci, pathovar glycinea, pathovar phaseolicola, and pathovar mori from other taxa with 100 and 92% bootstrap probabilities, respectively, suggesting that both hrpK and avrPphE had not experienced any intergroup horizontal gene transfer within P. syringae but have stably evolved along with the genome. In addition to phylogenetic analyses, average percentages of synonymous substitutions (ps) (31) of 0.0084 and 0.019 were found for avrPphE and hrpK, respectively, which indicates that the sequence divergence of avrPphE is less than that observed in hrpK orthologs.

FIG. 6.

Phylograms of optimal trees of EELs in P. syringae strains based on 250 bp of hrpK (A) and full-length avrPphE (B) sequences. Horizontal branch length is proportional to the estimated number of nucleotide substitutions, and bootstrap probabilities (as percentages) are indicated above or below the internal branches. The trees are rooted at the midpoint. Abbreviations for strains used in the figure follow: Psy, pathovar syringae; Pdp, pathovar delphinii; Pto, pathovar tomato; Pau, pathovar angulata; Pmo, pathovar mori; Pph, pathovar phaseolicola; Pgy, pathovar glycinea. In panel A, strains with EELs encoding ShcA-HopPsyA homologs are shown in shaded boxes. In panel B, the open box indicates that the avrPphE homolog used in phylogenetic analysis is not associated with the EEL.

DISCUSSION

We have cloned and sequenced the EELs from representative P. syringae pathovars and determined that three effector proteins of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL are substrates for the type III secretion pathway, have avirulence activity when individually expressed in P. syringae pv. tabaci, and contribute strongly to P. syringae pv. syringae B728a parasitic fitness. We chose to characterize the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL for several reasons: P. syringae pv. syringae B728a has been extensively studied in the laboratory and in the field, and a draft sequence of the genome is now available (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/JGI_microbial/html/pseudomonas_syr/pseudo_syr_homepage.html); the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL is the largest among all the isolated EELs; and all three effector proteins encoded by the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL have homologs in other phytopathogenic bacteria and therefore may be widely important in bacterial pathogenesis. Our observations invite several questions. For example, because bacterial genes (particularly horizontally transferred genes) are often clustered and organized into operons based on function (25), can we discern any functional significance to the presence of certain effectors in the EEL and, more specifically, in the HrpK operon? Can the effector compositions of EELs yield insights into the evolution of the P. syringae Hrp pathogenicity island and associated effectors?

Analyses of candidate effectors in the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL and their role in parasitism.

The ORFs in the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL represent a subset of effector genes that appear widespread among P. syringae pathovars. For example, HopPsyC is homologous with AvrB and AvrC, which were identified in soybean pathogen pathovar glycinea as avirulence factors (43). Both avrB and avrC are flanked by repeated DNA sequences (40) and have relatively low G+C content, which are characteristics of horizontally transferred genes. HopPsyV is even more widespread among pathogenic bacteria. It has motifs characteristic of the AvrRxv/YopJ family, whose members are also found in the genera Xanthomonas, Rhizobium, Salmonella, and Yersinia (5, 13, 16, 49). Yersinia YopJ inhibits the host immune response by preventing activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-κB pathways (32) and has been shown to require a cysteine protease catalytic triad for antihost activity (33). Mutations in the predicted catalytic core of AvrBsT, an AvrRxv homolog from X. campestris pv. campestris, completely abolished the ability of the protein to elicit necrosis when it was transiently expressed in N. benthamiana, suggesting that all members in the AvrRxv family might use a similar catalytic mechanism in bacterial pathogenesis (33).

The P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL hopPsyE protein is homologous with avrPphE, which has alleles in representative strains of all known races of pathovar phaseolicola, as well as in P. syringae pathovars tabaci (41), glycinea, angulata, delphinii (Table 3), and tomato DC3000 (http://www.tigr.org/cgi-bin/BlastSearch/blast.cgi?organism=p_syringae) and Ralstonia solanacearum (http://sequence.toulouse.inra.fr/R.solanacearum) (36) and Xanthomonas spp. (http://cancer.lbi.ic.unicamp.br/xanthomonas) (11). Although the pathovar tabaci AvrPphE and P. syringae pv. syringae B728a HopPsyE homologs share 77% amino acid sequence identity, it appears that a corresponding R gene in tobacco (N. tabacum cv. Xanthii) could differentiate these two and confer avirulence to the latter. As explained below, it appears that avrPphE homologs were acquired relatively early in P. syringae evolution and then maintained (with modifications in various strains to evade host R gene surveillance), which suggests that avrPphE plays an important role in bacterial pathogenesis.

Deletion of the EELs in P. syringae pv. syringae B728a and pathovar tomato DC3000 (2) had strikingly different effects on growth in planta. The P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL mutant grew poorly when inoculated by dipping, although it grew as well as the wild type when inoculated by infiltration. Because of this observation, we retested pathovar tomato DC3000 and its EEL mutant derivative CUCPB5110 in host tomato by dip inoculation. The bacterial population of the mutant was slightly reduced, which is similar to the previously reported phenotype (2), and no difference was found between the two inoculation methods (data not shown). Thus, the importance of the EEL effectors in P. syringae pv. syringae B728a and pathovar tomato DC3000 seems to be fundamentally different. It is noteworthy that a similarly strong growth penalty was observed with dip-inoculated but not infiltration-inoculated coronatine-deficient mutants of pathovar tomato DC3000 (27). This suggests that the pathovar tomato DC3000 coronatine and pathovar syringae B728a EEL effectors play a critical role in an early stage in pathogenesis that is bypassed when inoculum is infiltrated into leaf intercellular spaces. Whatever the explanation, dip inoculation is an important method in assessing the virulence of effector mutants.

P. syringae pv. syringae strains B728a and 61 differ in their relative growth and virulence in bean, and they differ in the composition of their EELs. The demonstrable importance of the P. syringae pv. syringae B728a EEL raised the possibility that the differing EELs could account for the differing virulence. Therefore, we heterologously expressed the strain B728a EEL in strain 61. However, wild-type strain 61 and strain 61 harboring the strain B728a EEL exhibited similar population dynamics and final population levels in planta, suggesting that there are other factors promoting bacterial growth in bean that must be missing in strain 61.

EELs isolated from different P. syringae pathovars reveal common and novel features.

To further explore the potential function of EELs and any significance of effector genes being located there, we analyzed the EELs of nine pathovars of P. syringae. The hrp genes provided a useful reference for this analysis because they appear to have evolved stably along with the P. syringae genome, as concluded by Sawada et al. (38) based on phylogenetic analyses using hrpL, hrpS, rpoD, and gyrB as indices. The avrPphE and hrpK gene trees constructed in this study agree well with previously reported taxonomic groups (9, 28, 38), indicating that avrPphE, like the hrp cluster, has been stable after its acquisition. The stability of avrPphE is also supported by the alleles found in pathovar tomato DC3000 and pathovar delphinii. Previous studies using PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the rrn operon (28) and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA and amplified fragment length polymorphism techniques (9) have shown that pathovars delphinii and tomato are relatively closer to each other than to pathovar phaseolicola, which agrees with our phylogenetic analyses that use avrPphE and hrpK as index genes. Interestingly, despite this similarity, the pathovar delphinii avrPphE gene is located in the EEL, and the pathovar tomato DC3000 avrPphE gene resides on a native plasmid (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/mdbinprogress.html).

The differing proportions of synonymous mutation, represented by ps in hrpL, hrpK, and avrPphE homologs, suggest that avrPphE may have been acquired later than hrpL and hrpK. The proportion of synonymous nucleotide substitutions (silent) in a protein-coding region indicates the evolutionary divergence of DNA sequences in closely related species (31). The ps of hrpL was reported to be 0.016 within the group of pathovar glycinea, pathovar tabaci, pathovar phaseolicola, and pathovar mori (38). In contrast, the variation in avrPphE (ps = 0.0084) is much lower than that calculated for hrpL and hrpK (ps = 0.019), which suggests that avrPphE was acquired in the EEL region after the bacterium had acquired the hrp cluster. However, since pathovars phaseolicola, glycinea, tabaci, and mori have different hosts, acquisition of avrPphE by the EEL must have occurred before adaptation to specific hosts. This hypothesis also predicts that members in the same taxonomic groups that have been defined by Sawada and others should have a similar suite of genes residing in the EEL, and indeed, a subset of candidate effectors, e.g., AvrPphE and HopPsyA, is commonly present in closely related P. syringae pathovars. Consistent with this concept, pathovar syringae strain 61 and strain 226 are in the same taxonomic group and apparently acquired the shcA-hopPsyA genes before they diverged into strains with different host specificity (20).

The sequences of the EELs also reveal that these loci are rich in mobile genetic elements and plasmid-related sequences, some of which are found in predicted ORFs (21). The EELs of pathovars mori and morsprunorum harbor effector pseudogenes with insertions and nonsense mutations in the coding sequence. This observation is consistent with the growing evidence that the devolution of certain virulence genes to pseudogenes is a significant factor in pathogen evolution (34). The existence of EELs containing only pseudogenes further argues against any intrinsic importance of effectors in this region of the P. syringae genome.

The variability that we observed in the composition of HrpK operons also argues against any functional significance to the location of particular effectors in the operon. For example, the schA-hopPsyA genes are in the HrpK operon in pathovar atrofaciens but in divergently oriented separate operons in pathovar syringae strains 61 and 226. Similarly, avrPphE homologs are in the HrpK operon in several of the strains that we analyzed but are carried on a plasmid in pathovar tomato DC3000, and multiple effector genes are downstream of hrpK in pathovars B728a and delphinii PDDCC 529. The HrpK operon thus appears to represent a locus where horizontal acquisition can result in recruitment of an effector gene into the Hrp regulon.

In summary, we have analyzed the structure of 12 EELs from nine P. syringae pathovars, including three that have been identified previously (2). Several general conclusions can be drawn. First, the locus residing between hrpK and tRNALeu in various P. syringae strains is indeed enriched in effector genes, three of which we have shown here to encode functional effectors. Second, the candidate effectors found in the EELs appear to represent a group of conserved effectors that are commonly present in plant pathogenic bacteria. For instance, there is a homolog of pathovar tomato DC3000 HopPtoB found in P. syringae pv. syringae B728a (http://www.jgi.doe.gov/JGI_microbial/html/pseudomonas_syr/pseudo_syr_mainpage.html), and AvrPphE homologs are widespread, as discussed above. Unlike CEL effectors, which seem to be specific to P. syringae and Erwinia spp., the EEL effectors appear to be more widespread and even include effectors with homologs in animal pathogens. Third, the composition of the EELs does not correlate with host range. For example, pathovar phaseolicola is a bean pathogen, whereas pathovar glycinea and pathovar tabaci are soybean and tobacco pathogens, respectively. Yet they all have highly similar avrPphE genes residing in their EELs. In contrast, the EELs of pathovar phaseolicola B130 and P. syringae pv. syringae B728a share low similarity despite both bacteria being bean pathogens. Fourth, the general congruence of the hrpK and avrPphE phylogenetic trees indicates that avrPphE was acquired early in the evolution of P. syringae before the divergence of modern host-specific pathovars. However, the relatively low number of synonymous mutations in various avrPphE homologs and the existence of EELs possessing hopPsyA or other effectors instead of avrPphE suggest that the effectors in modern EELs were acquired by P. syringae later than hrpK and the rest of the hrp/hrc gene cluster. Fifth, although the general congruence of the hrpK and avrPphE phylogenetic trees indicates that the EELs in many strains have been stable, the several variant EELs that we found violating this congruence suggest that effector “exchanges” can indeed be made in this region. In summary, our findings suggest that evolution of the P. syringae Hrp pathogenicity island occurred in stages, with the EELs and at least some of the effectors being acquired after the hrp/hrc gene cluster but before the divergence of modern pathovars.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

A similar approach was used to characterize the EEL regions of several additional strains and pathovars of P. syringae (J. C. Charity, K. Pak, C. F. Delwiche, and S. W. Hutcheson, Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact., in press).

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathie T. Hodge for assistance in phylogenetic analysis and helpful discussions, and Hye-Sook Oh for assistance in plant bioassays.

This work was supported by NSF grants MCB-9982646 and DBI-0077622.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfano, J. R., D. W. Bauer, T. M. Milos, and A. Collmer. 1996. Analysis of the role of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae HrpZ harpin in elicitation of the hypersensitive response in tobacco using functionally non-polar hrpZ deletion mutations, truncated HrpZ fragments, and hrmA mutations. Mol. Microbiol. 19:715-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfano, J. R., A. O. Charkowski, W.-L. Deng, J. L. Badel, T. Petnicki-Ocwieja, K. van Dijk, and A. Collmer. 2000. The Pseudomonas syringae Hrp pathogenicity island has a tripartite mosaic structure composed of a cluster of type III secretion genes bounded by exchangeable effector and conserved effector loci that contribute to parasitic fitness and pathogenicity in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4856-4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alfano, J. R., and A. Collmer. 1997. The type III (Hrp) secretion pathway of plant pathogenic bacteria: trafficking harpins, Avr proteins, and death. J. Bacteriol. 179:5655-5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfano, J. R., H. S. Kim, T. P. Delaney, and A. Collmer. 1997. Evidence that the Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae hrp-linked hrmA gene encodes an Avr-like protein that acts in an hrp-dependent manner within tobacco cells. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10:580-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergman, T., K. Erickson, E. Galyov, C. Persson, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1994. The lcrB (yscN/U) gene cluster of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is involved in Yop secretion and shows high homology to the spa gene clusters of Shigella flexneri and Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176:2619-2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charkowski, A. O., J. R. Alfano, G. Preston, J. Yuan, S. Y. He, and A. Collmer. 1998. The Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato HrpW protein has domains similar to harpins and pectate lyases and can elicit the plant hypersensitive response and bind to pectate. J. Bacteriol. 180:5211-5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Z., A. P. Kloek, J. Boch, F. Katagirl, and B. N. Kunkel. 2000. The Pseudomonas syringae avrRpt2 gene product promotes pathogen virulence from inside plant cells. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:1312-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciesiolka, L. D., T. Hwin, J. D. Gearlds, G. V. Minsavage, R. Saenz, M. Bravo, V. Handley, S. M. Conover, H. Zhang, J. Caporgno, N. B. Phengrasamy, A. O. Toms, R. E. Stall, and M. C. Whalen. 1999. Regulation of expression of avirulence gene avrRxv and identification of a family of host interaction factors by sequence analysis of avrBsT. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:35-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clerc, A., C. Manceau, and X. Nesme. 1998. Comparison of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA with amplified length fragment polymorphism to assess genetic diversity and genetic relatedness within genospecies III of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1180-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelis, G. R., and F. Van Gijsegem. 2000. Assembly and function of type III secretory systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:735-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.da Silva, A. C., J. A. Ferro, F. C. Reinach, C. S. Farah, L. R. Furlan, R. B. Quaggio, C. B. Monteiro-Vitorello, M. A. Van Sluys, N. F. Almeida, L. M. Alves, A. M. do Amaral, M. C. Bertolini, L. E. Camargo, G. Camarotte, F. Cannavan, J. Cardozo, F. Chambergo, L. P. Ciapina, R. M. Cicarelli, L. L. Coutinho, J. R. Cursino-Santos, H. El-Dorry, J. B. Faria, A. J. Ferreira, R. C. Ferreira, M. I. Ferro, E. F. Formighieri, M. C. Franco, C. C. Greggio, A. Gruber, A. M. Katsuyama, L. T. Kishi, R. P. Leite, E. G. Lemos, M. V. Lemos, E. C. Locali, M. A. Machado, A. M. Madeira, N. M. Martinez-Rossi, E. C. Martins, J. Meidanis, C. F. Menck, C. Y. Miyaki, D. H. Moon, L. M. Moreira, M. T. Novo, V. K. Okura, M. C. Oliveira, V. R. Oliveira, H. A. Pereira, A. Rossi, J. A. Sena, C. Silva, R. F. de Souza, L. A. Spinola, M. A. Takita, R. E. Tamura, E. C. Teixeira, R. I. Tezza, M. Trindade dos Santos, D. Truffi, S. M. Tsai, F. F. White, J. C. Setubal, and J. P. Kitajima. 2002. Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature 417:459-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ditta, G., S. Stanfield, D. Corbin, and D. R. Helinski. 1980. Broad host range DNA cloning system for Gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:7347-7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freiberg, C., R. Fellay, A. Bairoch, W. J. Broughton, A. Rosenthal, and X. Perret. 1997. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature 387:394-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guttman, D. S., and J. T. Greenberg. 2001. Functional analysis of the type III effectors AvrRpt2 and AvrRpm1 of Pseudomonas syringae with the use of a single-copy genomic integration system. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:145-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ham, J. H., D. W. Bauer, D. E. Fouts, and A. Collmer. 1998. A cloned Erwinia chrysanthemi Hrp (type III protein secretion) system functions in Escherichia coli to deliver Pseudomonas syringae Avr signals to plant cells and to secrete Avr proteins in culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10206-10211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardt, W. E., and J. E. Galan. 1997. A secreted Salmonella protein with homology to an avirulence determinant of plant pathogenic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9887-9892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirano, S. S., A. O. Charkowski, A. Collmer, D. K. Willis, and C. D. Upper. 1999. Role of the Hrp type III protein secretion system in growth of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a on host plants in the field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9851-9856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirano, S. S., and C. D. Upper. 2000. Bacteria in the leaf ecosystem with emphasis on Pseudomonas syringae—a pathogen, ice nucleus, and epiphyte. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:624-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, H.-C., S. W. Hutcheson, and A. Collmer. 1991. Characterization of the hrp cluster from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 and TnphoA tagging of genes encoding exported or membrane-spanning Hrp proteins. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 4:469-476. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, H.-C., R. Schuurink, T. P. Denny, M. M. Atkinson, C. J. Baker, I. Yucel, S. W. Hutcheson, and A. Collmer. 1988. Molecular cloning of a Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae gene cluster that enables Pseudomonas fluorescens to elicit the hypersensitive response in tobacco plants. J. Bacteriol. 170:4748-4756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue, Y., and Y. Takikawa. 1999. Investigation of repeating sequences in hrpL neighboring region of Pseudomonas strains. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 65:100-109. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keen, N. T. 1990. Gene-for-gene complementarity in plant-pathogen interactions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24:447-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keen, N. T., S. Tamaki, D. Kobayashi, and D. Trollinger. 1988. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 70:191-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King, E. O., M. K. Ward, and D. E. Raney. 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44:301-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence, J. G., and J. R. Roth. 1996. Selfish operons: horizontal transfer may drive the evolution of gene clusters. Genetics 143:1843-1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindemann, J., D. C. Arny, and C. D. Upper. 1984. Use of an apparent infection threshold population of Pseudomonas syringae to predict incidence and severity of brown spot of bean. Phytopathology 74:1334-1339. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma, S. W., V. L. Morris, and D. A. Cuppels. 1991. Characterization of a DNA region required for production of the phytotoxin coronatine by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 4:69-74. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manceau, C., and A. Horvais. 1997. Assessment of genetic diversity among strains of Pseudomonas syringae by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of rRNA operons with special emphasis on P. syringae pv. tomato. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:498-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansfield, J., C. Jenner, R. Hockenhull, M. A. Bennett, and R. Stewart. 1994. Characterization of avrPphE, a gene for cultivar-specific avirulence from Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola which is physically linked to hrpY, a new hrp gene identified in the halo-blight bacterium. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 7:726-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Nei, M., and T. Gojobori. 1986. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and non-synonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3:418-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orth, K., L. E. Palmer, Z. Q. Bao, S. Stewart, A. E. Rudolph, J. B. Bliska, and J. E. Dixon. 1999. Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase superfamily by a Yersinia effector. Science 285:1920-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orth, K., Z. Xu, M. B. Mudgett, Z. Q. Bao, L. E. Palmer, J. B. Bliska, W. F. Mangel, B. Staskawicz, and J. E. Dixon. 2000. Disruption of signaling by Yersinia effector YopJ, a ubiquitin-like protein protease. Science 290:1594-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parkhill, J. 2002. The importance of complete genome sequences. Trends Microbiol. 10:219-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritter, C., and J. L. Dangl. 1995. The avrRpm1 gene of Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola is required for virulence on Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 8:444-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salanoubat, M., S. Genin, F. Artiguenave, J. Gouzy, S. Mangenot, M. Arlat, A. Billault, P. Brottier, J. C. Camus, L. Cattolico, M. Chandler, N. Choisne, C. Claudel-Renard, S. Cunnac, N. Demange, C. Gaspin, M. Lavie, A. Moisan, C. Robert, W. Saurin, T. Schiex, P. Siguier, P. Thebault, M. Whalen, P. Wincker, M. Levy, J. Weissenbach, and C. A. Boucher. 2002. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Nature 415:497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Sawada, H., F. Suzuki, I. Matsuda, and N. Saitou. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pathovars suggests the horizontal gene transfer of argK and the evolutionary stability of hrp gene cluster. J. Mol. Evol. 49:627-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shan, L., P. He, J. M. Zhou, and X. Tang. 2000. A cluster of mutations disrupt the avirulence but not the virulence function of AvrPto. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:592-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staskawicz, B., D. Dahlbeck, N. Keen, and C. Napoli. 1987. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race 0 and race 1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J. Bacteriol. 169:5789-5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevens, C., M. A. Bennett, E. Athanassopoulos, G. Tsiamis, J. D. Taylor, and J. W. Mansfield. 1998. Sequence variations in alleles of the avirulence gene avrPphE.R2 from Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola lead to loss of recognition of the AvrPphE protein within bean cells and a gain in cultivar-specific virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 29:165-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swofford, D. L. 1998. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), 4th ed. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 43.Tamaki, S., D. Dahlbeck, B. Staskawicz, and N. T. Keen. 1988. Characterization and expression of two avirulence genes cloned from Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J. Bacteriol. 170:4846-4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsiamis, G., J. W. Mansfield, R. Hockenhull, R. W. Jackson, A. Sesma, E. Athanassopoulos, M. A. Bennett, C. Stevens, A. Vivian, J. D. Taylor, and J. Murillo. 2000. Cultivar-specific avirulence and virulence functions assigned to avrPphE in Pseudonmonas syringae pv. phaseolicola, the cause of bean halo-blight disease. EMBO J. 19:3204-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Dijk, K., D. E. Fouts, A. H. Rehm, A. R. Hill, A. Collmer, and J. R. Alfano. 1999. The Avr (effector) proteins HrmA (HopPsyA) and AvrPto are secreted in culture from Pseudomonas syringae pathovars via the Hrp (type III) protein secretion system in a temperature- and pH-sensitive manner. J. Bacteriol. 181:4790-4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Dijk, K., V. C. Tam, A. R. Records, T. Petnicki-Ocwieja, and J. R. Alfano. 2002. The ShcA protein is a molecular chaperone that assists in the secretion of the HopPsyA effector from the type III (Hrp) protein secretion system of Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1469-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vivian, A., and J. Mansfield. 1993. A proposal for a uniform genetic nomenclature for avirulence genes in phytopathogenic pseudomonads. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 6:9-10. [Google Scholar]

- 48.West, S. E. H., H. P. Schweizer, C. Dall, A. K. Sample, and L. J. Runyen-Janecky. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 128:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whalen, M. C., J. F. Wang, F. M. Carland, M. E. Heiskell, D. Dahlbeck, G. V. Minsavage, J. B. Jones, J. W. Scott, R. E. Stall, and B. J. Staskawicz. 1993. Avirulence gene avrRxv from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria specifies resistance on tomato line Hawaii 7998. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 6:616-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willis, D. K., E. M. Hrabak, S. E. Lindow, and N. J. Panopoulos. 1988. Construction and characterization of Pseudomonas syringae recA mutant strains. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1:80-86. [Google Scholar]