Abstract

Rhodococcus equi is a facultative intracellular opportunistic pathogen of immunocompromised people and a major cause of pneumonia in young horses. An effective live attenuated vaccine would be extremely useful in the prevention of R. equi disease in horses. Toward that end, we have developed an efficient transposon mutagenesis system that makes use of a Himar1 minitransposon delivered by a conditionally replicating plasmid for construction of R. equi mutants. We show that Himar1 transposition in R. equi is random and needs no apparent consensus sequence beyond the required TA dinucleotide. The diversity of the transposon library was demonstrated by the ease with which we were able to screen for auxotrophs and mutants with pigmentation and capsular phenotypes. One of the pigmentation mutants contained an insertion in a gene encoding phytoene desaturase, an enzyme of carotenoid biosynthesis, the pathway necessary for production of the characteristic salmon color of R. equi. We identified an auxotrophic mutant with a transposon insertion in the gene encoding a putative dual-functioning GTP cyclohydrolase II-3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase, an enzyme essential for riboflavin biosynthesis. This mutant cannot grow in minimal medium in the absence of riboflavin supplementation. Experimental murine infection studies showed that, in contrast to wild-type R. equi, the riboflavin-requiring mutant is attenuated because it is unable to replicate in vivo. The mutagenesis methodology we have developed will allow the characterization of R. equi virulence mechanisms and the creation of other attenuated strains with vaccine potential.

The facultative intracellular actinomycete Rhodococcus equi is a frequent and serious pathogen of young horses (foals) (15, 43) and an occasional but equally serious opportunistic pathogen of immunocompromised people (9, 23). It is one of the few bacteria capable of intramacrophage survival and replication, and thus, the study of this organism can provide insights into the biology of intracellular parasitism. The native host cell of R. equi is the alveolar macrophage, which is infected through inhalation of bacteria present in contaminated soil or dust. Infection results in pyogranulomatous pneumonia, which can be life threatening if appropriate long-term antibiotic therapy is not initiated or continued. Strains of R. equi isolated from pneumonic foals all possess a large (80- to 90-kb) virulence plasmid (47, 48), the entire nucleotide sequence of which has been recently determined (44). This plasmid is essential for virulence, as plasmid curing attenuates the bacterium and renders it harmless to foals (14, 50). Plasmid loss yields a strain incapable of replicating intracellularly, and thus, plasmid-encoded factors are necessary for both intramacrophage growth (19) and disease development in horses (14, 50). Interestingly, the virulence plasmid is only present in a subset of R. equi strains isolated from humans with rhodococcal pneumonia (45), indicating that chromosome-derived gene products also influence the disease process.

We lack a fundamental understanding of most aspects of R. equi pathogenesis. Very little is known about the genetic basis for R. equi virulence, and there exist no published data definitively identifying any single gene product as a determinant of virulence. We aspire to establish the bacterial genes required for virulence, to understand why disease develops in some hosts and not others, to ascertain how best to treat rhodococcal disease when it does develop, and, importantly, to construct preventative vaccines. In order to meet these goals, we must be able to create R. equi mutant strains, the study of which will aid in the dissection of the molecular basis of R. equi pathogenesis. Toward this end, we describe herein a mutagenesis system we developed for R. equi based on a member of the mariner family of transposons.

Transposon-based mutagenesis is a powerful technique that is virtually essential for conducting thorough investigations of bacterial virulence, and its use has led to the identification of virulence determinants in a variety of bacterial systems (13, 18, 29). The approach also provides a means by which to create attenuated bacterial strains with the potential for use as live attenuated vaccines and therefore may yield a path to disease prevention. Naturally occurring transposable elements have been discovered in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and subsequently engineered to construct insertional mutagenesis systems for several bacterial species by using both in vivo and in vitro delivery methods (16, 37). However, shortcomings of some of the commonly used transposable elements, which severely limit their utility, are site-specific integration and host range restriction, such as is observed with Tn10 integration in Mycobacterium spp. (7).

We chose to develop a mutagenesis system that employed the transposable element Himar1, a member of the mariner family of transposons, originally isolated from the horn fly (Haematobia irritans). A particular advantage of this element is its minimal site specificity. Apart from the dinucleotide TA, there are no evident sequence requirements for its insertion (25). In addition, Himar1 elements have no apparent need for host accessory factors (24). Furthermore, these elements have been demonstrated to transpose randomly in both eukaryotic cells (51) and bacteria, including Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium spp. (34, 38). We reasoned that a Himar1-based transposon would likewise insert randomly within the genome of R. equi, and herein we demonstrate that to be the case.

We used a conditionally replicating plasmid to deliver the minitransposon and efficiently generated a random mutant library in a virulent strain of R. equi. We have confirmed a lack of insertion site specificity and a minimum of target bias. Importantly, screening of the library easily identified several mutants, such as clones with color and capsular changes. In addition, we isolated a riboflavin auxotroph in which the transposon had inserted within the gene encoding the bifunctional enzyme GTP cyclohydrolase II-3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase, a component of the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway. We show that this riboflavin auxotroph is attenuated in an in vivo murine model system of R. equi infection and that it is a potential candidate vaccine for the prevention of R. equi disease in foals. We believe our mutagenesis system will be extremely useful in studying the pathogenesis of R. equi infection, the analysis of which has been so far hampered by a paucity of molecular tools with which to conduct a thorough genetic analysis of this organism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Virulent R. equi strain 103+ was originally isolated from a foal with R. equi pneumonia and was kindly provided by J. Prescott (Guelph, Ontario, Canada). The standard culture medium used was brain heart infusion (BHI; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) broth or agar, and unless otherwise noted, cultures were incubated at 30°C to maintain the presence of the R. equi virulence plasmid. Antibiotics, when necessary, were used at the following concentrations: apramycin, 80 μg/ml; hygromycin, 180 μg/ml. To restore color to the pyruvate kinase (pyk) mutant, pyruvic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. To restore growth of the riboflavin auxotroph on minimal medium, riboflavin (Sigma) was added at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. To prepare electrocompetent cells, R. equi 103+ was grown in BHI broth at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8 to 1.5. The culture was pelleted at 4°C, washed twice with cold distilled H2O, and finally resuspended in 1/20th of the original culture volume in cold 10% glycerol. Aliquots of 400 μl were then stored at −80°C. Electroporation was performed in 2-mm cuvettes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) at 2.5 kV and 720 Ω with 400 μl of thawed cells. Electroporated bacteria were recovered for 1 h at 30°C in 1 ml of BHI broth supplemented with 0.5 M sucrose and then plated onto BHI agar with appropriate antibiotics.

Construction of transposon delivery plasmid.

pMV261H, a Mycobacterium-E. coli shuttle plasmid, was cut with AgeI in order to isolate a 2,735-bp fragment containing a hygromycin resistance gene and an E. coli origin of replication (oriE). This fragment was then ligated to AgeI-digested pSC171.2 to create pJA103.2. pSC171.2 (kind gift of S. Chiang, Harvard University) is an E. coli vector that contains a multicloning site flanked by the inverted repeats of the Himar1 mariner transposon. Cloning at the AscI site of pSC171.2 placed the hygromycin resistance gene and the oriE gene inside of the transposon inverted repeats. Subsequent digestion of pJA103.2 with FspI/SapI yielded a 3,300-bp fragment containing the newly constructed hygromycin-marked, oriE-containing Himar1 minitransposable element. This fragment was blunted and ligated to pSC146 that had been previously digested with NsiI and BciVI and blunted with T4 DNA polymerase to create the conditionally replicating transposon delivery vector pJA2.2. pSC146 is a Mycobacterium-E. coli shuttle plasmid with a temperature-sensitive (ts) version of the pAL5000 mycobacterial origin of replication (oriM) (17). pSC146 also contains the gene encoding the mariner transposase and an apramycin resistance gene. The NsiI-BciVI digestion of pSC146 removed the oriE element from its backbone so that the transposon delivery vector, pJA2.2, contained a single oriE gene located within the inverted repeats of the transposon.

Transposon mutagenesis.

pJA2.2 (∼180 ng) was electroporated into R. equi, and transformants were selected on BHI agar supplemented with hygromycin (180 μg/ml) at 30°C. Plates were then scraped, and the bacteria were suspended in 20 ml of BHI broth. From this suspension, 100-μl aliquots were replated on BHI agar with hygromycin and incubated at the nonpermissive temperature of 42°C for 3 days to cure the cells of the transposon delivery vector. Transposon insertion mutants were identified by picking and patching of individual colonies in duplicate to BHI agar supplemented with either hygromycin or apramycin. Clones that were hygromycin resistant but sensitive to apramycin were deemed positive for transposition. Further confirmation of transposon insertion was attained by PCR analysis of positive clones for both the presence of the transposon and the absence of the apramycin resistance gene. The forward primer 5′-TTCACCGATCCGGAGGAACT-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TCCCCGGTCTCTAGAATTCA-3′ were used to amplify a 472-bp fragment of the transposon. To amplify the apramycin gene, the forward primer 5′-TCATCGGTCAGCTTCTCAAC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CACAGCAGTGGTCATTCTCG-3" were used.

Southern blot analysis.

Southern blotting was done to confirm the insertion of a single transposon within an individual clone. In order to isolate total nucleic acids, a 6-ml overnight culture of the clone of interest was pelleted and resuspended in 500 μl of 10 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, with 100 μg of lysozyme per ml. After incubation for 3 h to overnight at 37°C, 70 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 6 μl of 10 mg of proteinase K per ml (final concentration, 100 μg/ml) were added and a 1-h incubation at 65°C was done. Next, 100 μl of 5 M NaCl was added and the solution was gently mixed. This was followed by the addition of 80 μl of 10% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide in 0.7 M NaCl, and the mixture was incubated for 20 min at 65°C. Subsequently, DNA was extracted by using phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and precipitated with 0.6 volume of 100% isopropanol. DNA from positive clones was digested with XmaI, which does not cut within the transposon, and then the DNA fragments were resolved on a 1% agarose gel. DNA was then transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). Blots were probed with a purified 472-bp PCR fragment (described above) specific to the transposon, which had been labeled by using the ECL direct nucleic acid labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Processing of the gel, probe labeling, and detection were carried out in accordance with the manufacturers' recommendations.

Mutant screens.

The transformed R. equi library was plated on BHI agar supplemented with hygromycin and incubated at 42°C for 3 days. Plates were then transferred to 30°C for 2 days to allow the clones to grow large enough to examine. Some of the clones that showed significant morphological changes, such as alterations in color or capsule, were picked and patched onto BHI agar with hygromycin and BHI agar with apramycin. Those clones that were hygromycin resistant but apramycin susceptible were analyzed by colony PCR to confirm the presence of a transposon, loss of the donor plasmid apramycin resistance gene, and the presence of vapA, indicating maintenance of the R. equi virulence plasmid. To amplify vapA, the forward primer 5′-GGCGTCGCTGGGCCCACCGTTCTTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TACGTGCAGCGAATTCGGCGTTGTGC-3′ were used.

To screen for R. equi auxotrophs, individual clones from the transposon mutant library were picked and patched to BHI agar with hygromycin, as well as minimal medium with hygromycin. Minimal salts medium was composed of 30 mM K2HPO4, 16.5 mM KH2PO4, 78 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.85 mM sodium citrate, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.02% glycerol, and 0.0016% thiamine. Clones that grew on BHI agar but not on minimal medium were further analyzed by PCR as discussed above to confirm the presence of the virulence plasmid-encoded vapA gene and the transposon and to document the loss of the apramycin resistance gene.

Sequencing.

Total DNA was isolated from the R. equi clones. To recover the R. equi insertion site, DNA was digested with XmaI, self-ligated, and then electroporated into E. coli strain DH10B (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Transformants were selected on LB (Difco) agar supplemented with hygromycin (180 μg/ml). Plasmid DNA containing the R. equi transposon insertion was isolated from E. coli by the Nucleospin (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) miniprep procedure and submitted for sequencing to the Microbiology Core Sequencing Facility (Harvard Medical School). Sequencing from the transposon ends was done with the outward-directed primer pairs 5′-ATCATCAGGGCTCGACGGGA-3′ and 5′-CAAGTTGTCCTCGCTGCCAC-3′ or primer pairs 5′-GCTCTTAGCGGCCCGGAAACGTCCTCGAAA-3′ and 5′-CTTGGCCATTGCGAAGTGATTCCTCCGGAT-3′. These primer sets annealed to regions within the transposon so that the sequence results displayed the transposon end, as well as the adjacent R. equi DNA sequence.

Mouse infection.

Female BALB/cJ mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and infected at approximately 8 weeks of age. Frozen aliquots of the bacterial strains with known titers were thawed, cultured for 1 h at 37°C, pelleted, and then diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Even though the titers of the frozen bacterial aliquots had been determined previously, the titer of the inoculum was reconfirmed at the time of injection by dilution plating of the injection stock. Groups of mice were injected intravenously in the tail veins with 3 × 105 to 7 × 105 CFU of wild-type R. equi 103+ or the riboflavin auxotroph in 100 μl of PBS. In order to monitor bacterial clearance or growth, at various times postinjection, four mice from each experimental group were sacrificed and their spleens, livers, and lungs were aseptically removed. Each organ was placed in PBS and disrupted with a Stomacher-80 apparatus (Tekmar, Cincinnati, Ohio). Serial 10-fold dilutions of the tissue homogenate were plated onto BHI agar supplemented with riboflavin and/or antibiotic when appropriate. Plates were incubated at 37°C, and CFU were counted 36 h later.

RESULTS

In vivo transposition in R. equi.

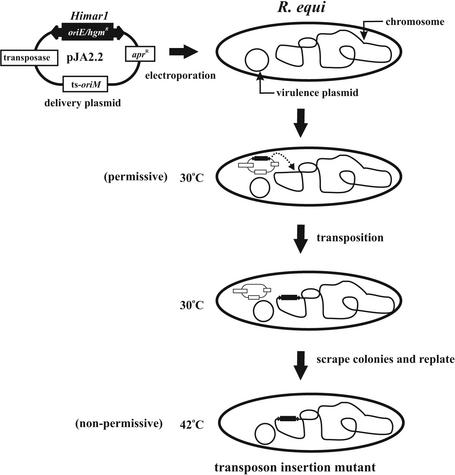

In order to meet our goal of creating attenuated mutants of the facultative intracellular actinomycete R. equi, we decided to develop an in vivo mutagenesis system. Since transposons belonging to the mariner family have been shown to transpose randomly in a variety of organisms, including insects, protozoa, and bacteria (34), we decided to use the Himar1 element as the foundation upon which to build our mutagenesis methodology. To deliver the minitransposon to R. equi, we ultimately developed a protocol that involved the use of a conditionally replicating plasmid. We had previously determined that the Mycobacterium pAL5000 origin of replication (oriM) could maintain an episomal plasmid in R. equi (14). We next confirmed that an oriM-based replicon could be retained even in the presence of the R. equi virulence plasmid (data not shown). We then sought to determine if a ts version of pAL5000 (17) was likewise ts in R. equi. Therefore, we transformed virulent R. equi strain 103+ with a Mycobacterium-E. coli shuttle plasmid (pSC146) containing the ts oriM gene and selected transformants at 30°C (permissive temperature) on BHI agar plates containing hygromycin. To determine if the oriM gene in pSC146 was ts in R. equi, we scraped the transformants from the plates held at 30°C and replated duplicate dilutions of the transformed bacteria on hygromycin-containing plates and incubated a set of plates at 30°C and another at 42°C (nonpermissive temperature), a temperature that is not lethal to the bacterium. We observed a 5,000-fold reduction in the number of transformed bacteria at 42°C compared to 30°C, indicating that the oriM gene was indeed ts in R. equi, as indicated by its ability to function at 30°C but not at 42°C. Therefore, we included this ts oriM gene in the backbone of our minitransposon delivery vehicle.

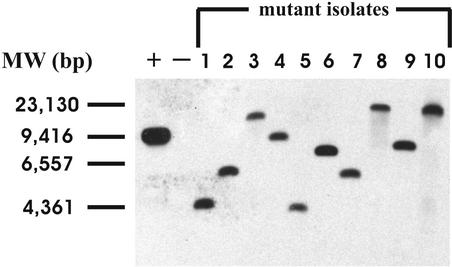

In order to generate insertion mutants, we constructed the delivery plasmid pJA2.2, which contains the Himar1 transposase, ts oriM, and apramycin resistance genes located on its backbone, as well as a Himar1 minitransposon element containing a hygromycin resistance gene cassette and an E. coli origin of replication (oriE) positioned within the inverted repeats. This was the only E. coli origin of replication on the delivery plasmid, and its presence helped to facilitate recovery of the transposon insertions, as described later. pJA2.2 was introduced into R. equi 103+ by electroporation (Fig. 1). Transformants were selected on hygromycin plates at 30°C to allow plasmid replication and transposition. Transformants were then scraped off the plates and resuspended in medium, and aliquots were replated and incubated at either 30°C (to determine the number of cells in suspension) or 42°C, a temperature at which the delivery plasmid cannot replicate. As before, plates that were incubated at 42°C had approximately 5,000-fold fewer colonies than the plates incubated at 30°C. All of the colonies that arose at 42°C were hygromycin resistant, and PCR analysis confirmed that this resistance correlated with the presence of the transposon. Ninety-eight percent of the clones surviving at 42°C were sensitive to apramycin, indicating loss of the delivery plasmid since the apramycin resistance gene was on the vector backbone and not contained within the transposon. Southern blot analysis of randomly chosen insertion mutants determined that 49 of the 50 examined contained a single transposon insertion. Figure 2 shows a Southern analysis of 10 such mutants. Total DNA was isolated from the R. equi insertion mutants and digested with XmaI, an enzyme that cuts frequently within R. equi DNA but not within the transposon. Blots were probed with a DNA fragment within the Himar1 element obtained by PCR as mentioned in Materials and Methods. The mutants with a single transposon insertion displayed one band upon Southern blotting (Fig. 2), whereas multiple bands would be observed if clones contained more than one insertion.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of in vivo transposition mutagenesis in R. equi. Plasmid pJA2.2, containing the Himar1 transposase, a ts origin of replication (oriM), and a Himar1 element marked with a hygromycin resistance gene and carrying an E. coli origin of replication (oriE), was electroporated into R. equi, and transformants were recovered on hygromycin plates at 30°C (permissive temperature) to allow for transposition (as indicated by the dashed arrow). Transformants were subsequently scraped from the plates and resuspended in medium, and aliquots were replated on hygromycin-containing agar. Plates were incubated at 42°C (nonpermissive temperature) to isolate transposon insertion mutants.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of 10 randomly chosen transposon insertion mutants. Total DNA from the R. equi mutants (lanes 1 to 10) and wild-type R. equi (lane −; negative control) was isolated and digested with XmaI, an enzyme that does not cut within the transposon. The blot was probed with a 472-bp fragment of the Himar1 transposon. The leftmost lane contained linearized transposon delivery plasmid pJA2.2, which served as a positive control (+). Molecular size markers (in base pairs) are indicated on the left.

In order to more thoroughly characterize the composition of the R. equi transposon mutant library, we sequenced the insertion junctions of 100 randomly selected mutants. For this purpose, total DNA from individual clones was digested to completion with XmaI. The DNA fragments were self-ligated and transformed into E. coli. DNA fragments containing the transposon insertion would replicate in E. coli by virtue of the presence of the oriE gene within the transposon. Such clones were recovered on LB agar plates containing hygromycin, and plasmid DNA was subsequently isolated and submitted for sequencing of the DNA regions flanking the transposon insertion site. In the 100 clones examined, 87 unique insertion sites were identified. Five of the 100 clones sequenced were not insertions but rather represented delivery plasmid pJA2.2, which had survived the nonpermissive selection. Eight of the clones were identified twice and, thus, likely represented siblings. Twenty-four of the insertions occurred in DNA sequences with no significant homology to anything in the databases and may represent insertions into intergenic regions or open reading frames (ORFs) unique to R. equi. Several insertions (40%) were within sequences displaying the highest degree of homology to Mycobacterium spp., including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. leprae, and M. smegmatis. As has been reported for other mariner elements, all insertions occurred at a TA dinucleotide and no other insertion consensus sequence was recognized. Some slight target bias was seen; specifically, the ORF of a putative penicillin-binding protein was disrupted three times, albeit at unique sites, and a probable rRNA gene was identified twice, although once again, each insertion was distinct. Table 1 displays a sampling of some of the Himar1 insertions identified.

TABLE 1.

Sampling of Himar1 insertion site sequences in R. equi

| Sequence at junctiona | Similar ORF | Organism | Putative functionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAGTAGCGCCGGACCT | ML1582 | M. leprae | Metalloprotease |

| TACGTCAACCGCGAGC | garA | M. tuberculosis | Signal transduction |

| TACATGACATCTTCCT | ML1157 | M. leprae | 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase |

| TACTGCCATGCGACGA | Cg10188 | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Arabinosyl transferase |

| TATGTCCCACAATCCG | None | ||

| TACCCTGGTGAACCAT | glmS | M. tuberculosis | Glucosamine fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase |

| TACGGCACCTCGAAGG | fabG4 | M. tuberculosis | Acyl carrier protein |

| TACCTCGGTGACGCCG | amt | M. tuberculosis | Ammonium transporter |

| TACGTGTCGACGAGCA | Cg12467 | C. glutamicum | Nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase |

| TAGGTGGCGATCGACG | iunH | M. tuberculosis | Inosine-uridine preferring nucleoside hydrolase |

| TAGTCGACCTGCTCGG | fadA | Streptomyces coelicolor | Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase |

| TACCTCGTGATCGGCG | ML1504 | M. leprae | Unknown membrane protein |

| TACCTGCCAGTTCGAG | nthIII | M. tuberculosis | Endonuclease |

| TACACCGCGCCACGCC | Cg11534 | C. glutamicum | Quinone reductase |

| TACGTCGGGCCCGACG | Rv0345 | M. tuberculosis | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| TAGGGTCCCGAGATGT | lpqB | M. tuberculosis | Lipoprotein |

| TACCTGGAGTCGTTCC | Rv0635 | M. tuberculosis | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| TACGTAGGGTGCGAGC | 16S rRNA | R. equi | |

| TACGAGTGAAGAGCGT | Rv2553c | M. tuberculosis | Thymidylate kinase |

| TAGTCGGCGGGATCCT | pth | M. tuberculosis | Peptidyl tRNA hydrolase |

Boldface indicates the duplicated TA dinucleotide at the target site.

Homologous ORFs were identified by searching the GenBank database with the tblastx, blastx, and RPS-BLAST search functions.

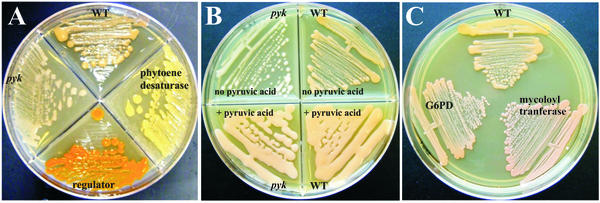

Selection of color and morphology mutants.

We reasoned that if the Himar1 element was indeed inserted randomly within the R. equi genome, it should be possible to readily identify mutants with insertions resulting in altered pigmentation. R. equi is normally salmon pink in color because of the production of γ-carotene (20). Out of 7,920 transposon insertion mutants screened, we identified four nonpigmented, nine yellow, and eight bright orange clones. A comparative screening of twice that number of wild-type R. equi colonies identified none with changed color. Figure 3A shows the contrast of the mutant pigment phenotypes to that of wild-type R. equi. Sequence analysis of the insertion junction of a yellow mutant determined that the transposon had disrupted an ORF with homology to a Brevibacterium phytoene desaturase gene, an enzyme involved in carotenoid biosynthesis. Insertion site analysis of an orange pigmentation mutant showed homology to several DNA repressors. Comparable sequencing of a nonpigmented mutant determined that the transposon had been inserted into an ORF with high homology to the gene for pyruvate kinase (pyk). To evaluate whether the transposon insertion in the pyruvate kinase gene was responsible for the observed nonpigmented phenotype, we plated the clone on BHI medium supplemented with pyruvic acid. Indeed, the addition of pyruvate restored the wild-type, salmon-colored pigmentation to the mutant (Fig. 3B), data consistent with a transposon-linked phenotype.

FIG. 3.

Transposon mutants of R. equi. (A) Photograph of three transposon-derived pigmentation mutants of R. equi and comparison with the wild type (WT). Himar1 transposon mutagenesis of R. equi was performed as described in Materials and Methods and as diagramed in Fig. 1. Wild-type R. equi is located at the 12 o'clock position. A yellow-colored mutant containing an insertion in an ORF with homology to the gene for phytoene desaturase is in the right quadrant; an orange-pigmented mutant, at the 6 o'clock position, contained a transposon insertion in a region with homology to various repressor proteins; an insertion in an ORF with high homology to the gene for pyruvate kinase (pyk) was found in the colorless mutant in the left quadrant. (B) Pyruvic acid supplementation restores normal pigmentation to the nonpigmented pyruvate kinase (pyk) mutant. Wild-type R. equi and the pyk mutant were streaked onto BHI agar with and without the addition of pyruvic acid. (C) Himar1 transposon mutants of R. equi with altered capsular phenotypes and comparison to the wild-type parental strain. One of the dry mutants contained a transposon disruption of an ORF with homology to glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), and the other was found to have a transposon insertion in an ORF with homology to Mycobacterium mycoloyl transferases.

As a further test of the utility of the R. equi transposon library, we also looked for mutants with alterations in surface characteristics. For example, owing to the presence of a polysaccharide capsule (31, 35), wild-type R. equi is mucoid in appearance. Out of the same 7,920 mutant clones screened as described above, we noted 221 that were less mucoid than wild-type R. equi. As before, screening of two times this number of wild-type colonies discovered none with apparent alterations in the character of the bacterial surface. Further evaluation of two of the “dry” clones (Fig. 3C) showed one to have a transposon insertion in the pentose phosphate pathway enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and the other to have an insertion in a region with high homology to mycoloyl transferases of Mycobacterium spp. and Corynebacterium spp. The pentose phosphate pathway is intimately linked to lipid biosynthesis, and mycoloyl transferases are involved in transfer of mycolic acids to arabinogalactan cell wall residues (21, 36). Mutations of either of these enzymes would be consistent with altered lipid metabolism, thereby affecting cell wall lipids and indirectly affect capsule-cell wall association.

Identification and in vivo characterization of a riboflavin auxotroph.

Because the ultimate goals of our work are to learn something of the pathogenesis of R. equi and to create attenuated strains of the bacterium that may be useful as vaccines, we decided to look for auxotrophic mutants of the organism. Auxotrophs are strains that require particular exogenous nutritional supplementation for growth, and they have demonstrated utility in a variety of bacterial systems as live attenuated vaccines (1, 26, 42). Thus, we screened approximately 1,000 R. equi transposon mutants and identified 10 that could grow on BHI medium but not on minimal salts medium. One of these mutants was found to have a unique transposon insertion in an ORF with extensive homology to the bifunctional enzyme comprising a GTP cyclohydrolase II and 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase, an enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of the vitamin riboflavin. Subsequent supplementation of minimal salts medium with riboflavin restored the growth of these mutants, a finding consistent with the hypothesis that transposon disruption of the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway was responsible for the auxotrophic phenotype.

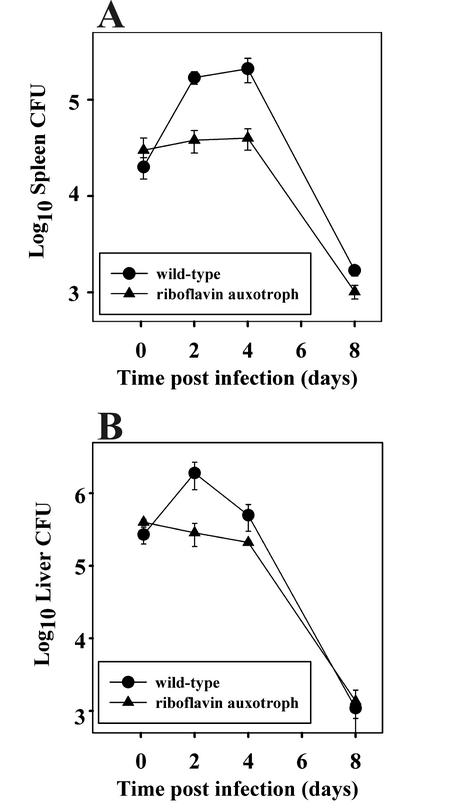

As riboflavin auxotrophy has been demonstrated to attenuate another pathogen, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (12), we sought to determine whether the riboflavin auxotroph of R. equi would be similarly affected for growth in vivo. Therefore, BALB/cJ mice were infected with the riboflavin mutant and the clearance of the auxotroph was compared to that of wild-type R. equi. Although the mouse does not develop rhodococcal pneumonia, virulent (virulence plasmid-containing) strains of R. equi will replicate in vivo over the short term (46), and this ability to replicate in the mouse has been correlated to virulence in foals (14, 50). In mice intravenously challenged with wild-type R. equi, the bacteria increase in number approximately 5-fold in the liver and 10-fold in the spleen during the first 48 h postchallenge, after which time the bacterial burden plateaus (Fig. 4). At some time around day 5 postinfection, clearance of the bacteria becomes apparent and bacterial numbers quickly decline. The infection is generally resolved in approximately 3 weeks, depending on the size of the initial inoculum (27, 46). In contrast to the in vivo growth displayed by wild-type R. equi, the riboflavin auxotroph did not replicate. Rather, it persisted at the challenge level for 4 to 5 days postinfection, after which its numbers steadily declined at a rate similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 4). We confirmed that the virulence plasmid was present in the riboflavin mutant (data not shown), and therefore, the observed attenuation of the strain cannot be attributed to virulence plasmid loss. Thus, the inability of the mutant to synthesize riboflavin rendered it incapable of in vivo growth in a murine R. equi virulence model.

FIG. 4.

Clearance of wild-type R. equi and a riboflavin auxotroph of R. equi in immunocompetent BALB/cJ mice. Mice were infected via the lateral tail vein with 3 × 105 to 7 × 105 CFU of wild-type R. equi (•) or a similar number of riboflavin mutant CFU (▴). At the indicated times postinfection, mice were sacrificed and their organs were collected and homogenized. The bacterial burdens in the spleen (A) and liver (B) were determined by serial dilution and plating of the homogenates onto BHI agar. The error bars represent the standard deviations of the means of four mice per experimental group.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of R. equi pathogenesis has been hindered by the lack of a genetic system and a means by which to readily create mutants. For that reason, we set out to develop a mutagenesis protocol for R. equi founded on transposon-mediated gene disruption. We decided to construct an in vivo mutagenesis system by using a Himar1 transposon since that element has demonstrated efficacy in achieving high-density insertions in a related bacterial species (40).

Himar1 is a member of the mariner family of short-inverted, terminal repeat-type mobile DNA elements that are transposed via a simple cut-and-paste mechanism (34). Members of the mariner family have terminal repeat structures that are among the simplest and shortest known (34); for example, the transposon used in this study is flanked by a 29-bp repeat sequence. mariner integration reportedly occurs almost exclusively at a TA dinucleotide (34), a finding we documented in 100% of the R. equi insertion mutants. We have confirmed a lack of target specificity because no consensus sequence was identified beyond that of the TA integration site. Importantly, even in the GC-rich genome of R. equi, insertion was random and a variety of unique insertions were obtained; specifically, 87 out of 100 clones examined contained a distinct insertion. We observed a minimum of target bias, which is consistent with what has been reported for mariner transposition in other systems (25, 38). During the course of this work, another laboratory reported using a commercially available system to achieve transposome-mediated gene inactivation in R. equi (28). We had attempted a similar approach, but our use of that method met with limited success and was not as efficient as the Himar1-based system we created (unpublished data).

R. equi is a member of the class Actinomycetales and has many of the same physical, biochemical, and cell biological characteristics as another actinomycete, M. tuberculosis (30). Given their similarities and the relative lack of genetic tools available for analyzing R. equi, we reasoned that we should be able to make use of reagents used in the study of Mycobacterium spp. In fact, we had previously determined that the oriM gene derived from the M. fortuitum pAL5000 plasmid could stably maintain an episomal E. coli-Mycobacterium shuttle vector in R. equi (14). We tested a ts version of the oriM gene (17) in R. equi and found that it was similarly ts. In R. equi transformed with our transposon delivery plasmid containing the ts oriM gene, growth at the nonpermissive temperature (42°C) resulted in a 5,000-fold reduction in the number of colonies compared to that obtained at the permissive temperature (30°C), a reduction level similar to that observed in M. tuberculosis (32). We concluded that it is feasible to use a conditionally replicating plasmid as a means to deliver the Himar1 transposon to R. equi, as had been done in M. smegmatis (38). We note that a limitation of this delivery method is the potential for the generation of sibling mutants. Insertions occurring early in the permissive outgrowth period can be overrepresented following replating and incubation at the nonpermissive temperature. To correct for this, it may be necessary to screen additional clones in order to identify a particular phenotype. Nonetheless, we were successful in isolating mutants from several mutant screens.

The utility of the Himar1 mutagenesis is illustrated by the ease with which we obtained R. equi clones with altered pigmentation. R. equi, like many species of bacteria, fungi, and plants, produces tetraterpenoid pigments known as carotenoids that are derived from the general isoprenoid biosynthesis pathway (8). These yellow, orange, and red pigments provide protection against photo-oxidative damage (3, 49). A C40 hydrocarbon backbone is common to all carotenes and is generated by the condensation of two molecules of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate to create the colorless intermediate phytoene (2, 39). Phytoene then undergoes a series of desaturation reactions catalyzed by phytoene desaturase, producing the sequential intermediates phytofluene, ζ-carotene, and neurosporene and the maximally desaturated molecule lycopene (39). A single cyclization reaction at one end of lycopene yields γ-carotene, the pigment found in abundance in R. equi (20).

We screened an R. equi transposon library for mutants with altered coloration that would be indicative of the disruption of genes involved in carotenoid biosynthesis. Several such mutants were identified. One of the mutants chosen for further analysis was colorless. Carotenoid pathway mutants that fail to produce phytoene, lack all carotenes, and are colorless (4). Our nonpigmented R. equi mutant contained a transposon insertion into an ORF with high homology to the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase (encoded by the pyk gene). Pyruvate kinase mediates the transfer of phosphate from phosphoenolpyruvate to ADP, yielding ATP and pyruvate, a precursor of acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA). The first isoprenoid precursor is acetate, in the form of acetyl-CoA. We reasoned that, because of an inability to make sufficient amounts of pyruvate, the nonpigmented R. equi pyruvate kinase mutant might not make adequate acetyl-CoA to ultimately generate the pigmented carotenoids. To help determine if the transposon disruption was the cause of the altered pigmentation, we grew the pyruvate kinase mutant in the presence of exogenous pyruvate. We found that pyruvate supplementation restored wild-type pigmentation to the mutant, a finding consistent with the idea that the transposon disruption of pyruvate kinase had caused the loss of pigmentation.

Transposon mutagenesis has been used to discover the structural and regulatory genes of carotenoid biosynthesis in the bacterium Myxococcus xanthus (10), and the sequence of M. xanthus phytoene desaturase was identified in this way. We also identified a phytoene desaturase insertion in a screen for R. equi pigmentation mutants. Phytoene desaturase is the enzyme responsible for introducing double bonds into the C40 hydrocarbon carotenoid backbone. In the absence of any biochemical characterization, we cannot definitively know what carotenoid(s) accumulates in this mutant. However, neurosporene is a yellow pigment and thus, an alteration of phytoene desaturase that results in neurosporene accumulation would be consistent with the yellow color of this mutant. In an orange-reddish-colored mutant, the sequence adjacent to the transposon showed homology to several transactivators and repressors. Mutations in regulatory genes have been demonstrated to result in altered carotenoid accumulation and subsequent changes in pigmentation (33). Thus, it is possible that the function of a regulatory gene was disrupted, causing accumulation of the reddish carotenoid lycopene, which produced the observed color change (4) in this mutant.

Since a primary goal of our work is to create attenuated strains of R. equi, we screened for insertion mutants that are unable to grow on minimal salts medium; in so doing, we identified a riboflavin (vitamin B2) auxotroph. This mutant contains an insertion in an ORF with extensive homology to the bifunctional enzyme containing GTP cyclohydrolase II and 3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase activities, components of the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway. In general, wild-type R. equi grows poorly on minimal medium but the riboflavin auxotroph does not grow at all, and we confirmed that the mutant could be rescued on minimal medium if exogenous riboflavin was provided.

Riboflavin is the precursor of the coenzymes flavin mononucleotide phosphate and flavin adenine dinucleotide phosphate, compounds essential for growth and cell division (6). Riboflavin can be synthesized by fungi, plants, and bacteria but not by higher eukaryotes (5). Some bacteria are readily able to make use of exogenous sources of riboflavin (22), but even if a bacterium is in possession of an adequate uptake system, the mammalian environment may be so limiting in riboflavin availability that bacterial growth is prevented. Such a scenario was documented by studies of the veterinary pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, in which a riboflavin auxotroph was demonstrated to be incapable of causing disease in swine (11, 12). Thus, we investigated whether the R. equi riboflavin mutant would be similarly attenuated in vivo by using a murine challenge model. Although immunocompetent mice are relatively resistant to R. equi infection, virulent strains of the bacteria will replicate in the early days postinfection, whereas attenuated strains will not (46). Furthermore, the ability to replicate in the tissues of the mouse has been demonstrated to correlate with the ability of R. equi to cause disease in foals (14, 50). We therefore infected mice with both virulent prototrophic R. equi bacteria and a similar number of the riboflavin mutant bacteria and monitored the in vivo grow of both strains, and we discovered that riboflavin auxotrophy is indeed attenuating to R. equi (Fig. 4). This work provides the first demonstration of attenuation of R. equi due to disruption of a metabolic gene. Since auxotrophic mutants can be useful as live attenuated vaccine candidates (1, 26, 42), we are interested in examining the immunizing capabilities of the R. equi riboflavin auxotroph in the hope of developing a vaccine strain to protect foals against rhodococcal disease. Furthermore, we are interested in studying other attenuating mutations and are now in a position to apply additional transposon-mediated approaches, such as signature-tagged mutagenesis (41), to identify components and pathways necessary for R. equi virulence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ilona Breiterene for technical assistance with the murine infection experiments and Eric Rubin for providing the Himar1 element and for helpful discussions regarding this work. Appreciation is extended to Shruti Jain, Martin Pavelka, and Adrie Steyn for offering a critical review of the manuscript.

These studies were supported in part by funds provided by the Grayson Jockey Club Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, Z. U., M. R. Sarker, and D. A. Sack. 1990. Protection of adult rabbits and monkeys from lethal shigellosis by oral immunization with a thymine-requiring and temperature-sensitive mutant of Shigella flexneri Y. Vaccine 8:153-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong, G. A. 1994. Eubacteria show their true colors: genetics of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis from microbes to plants. J. Bacteriol. 176:4795-4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong, G. A., M. Alberti, and J. E. Hearst. 1990. Conserved enzymes mediate the early reactions of carotenoid biosynthesis in nonphotosynthetic and photosynthetic prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:9975-9979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrach, N., R. Fernandez-Martin, E. Cerda-Olmedo, and J. Avalos. 2001. A single gene for lycopene cyclase, phytoene synthase, and regulation of carotene biosynthesis in Phycomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1687-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacher, A. 1991. Biosynthesis of flavins, p. 215-259. In F. Muller (ed.), Chemistry and biochemistry of flavins, vol. 1. Chemical Rubber Company, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 6.Bacher, A., S. Eberhardt, and G. Richter. 1996. Biosynthesis of riboflavin, p. 657-664. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Bardarov, S., J. Kriakov, C. Carriere, S. Yu, C. Vaamonde, R. A. McAdam, B. R. Bloom, G. F. Hatfull, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1997. Conditionally replicating mycobacteriophages: a system for transposon delivery to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10961-10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Britton, G. 1983. The biochemistry of natural pigments. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

- 9.Emmons, W., B. Reichwein, and D. L. Winslow. 1991. Rhodococcus equi infection in the patient with AIDS: literature review and report of an unusual case. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontes, M., R. Ruiz-Vazquez, and F. J. Murillo. 1993. Growth phase dependence of the activation of a bacterial gene for carotenoid synthesis by blue light. EMBO J. 12:1265-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller, T. E., B. J. Thacker, C. O. Duran, and M. H. Mulks. 2000. A genetically-defined riboflavin auxotroph of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae as a live attenuated vaccine. Vaccine 18:2867-2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuller, T. E., B. J. Thacker, and M. H. Mulks. 1996. A riboflavin auxotroph of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is attenuated in swine. Infect. Immun. 64:4659-4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaillard, J. L., P. Berche, and P. Sansonetti. 1986. Transposon mutagenesis as a tool to study the role of hemolysin in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 52:50-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giguere, S., M. K. Hondalus, J. A. Yager, P. Darrah, D. M. Mosser, and J. F. Prescott. 1999. Role of the 85-kilobase plasmid and plasmid-encoded virulence-associated protein A in intracellular survival and virulence of Rhodococcus equi. Infect. Immun. 67:3548-3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giguere, S., and J. F. Prescott. 1997. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Rhodococcus equi infections in foals. Vet. Microbiol. 56:313-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin, T. J. T., L. Parsons, A. E. Leschziner, J. DeVost, K. M. Derbyshire, and N. D. Grindley. 1999. In vitro transposition of Tn552: a tool for DNA sequencing and mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3859-3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guilhot, C., B. Gicquel, and C. Martin. 1992. Temperature-sensitive mutants of the Mycobacterium plasmid pAL5000. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 77:181-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulig, P. A., and R. Curtiss III. 1988. Cloning and transposon insertion mutagenesis of virulence genes of the 100-kilobase plasmid of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 56:3262-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hondalus, M. K., and D. M. Mosser. 1994. Survival and replication of Rhodococcus equi in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 62:4167-4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichiyama, S., K. Shimokata, and M. Tsukamura. 1989. Carotenoid pigments of genus Rhodococcus. Microbiol. Immunol. 33:503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson, M., C. Raynaud, M. A. Laneelle, C. Guilhot, C. Laurent-Winter, D. Ensergueix, B. Gicquel, and M. Daffe. 1999. Inactivation of the antigen 85C gene profoundly affects the mycolate content and alters the permeability of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1573-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kearney, E. B., J. Goldenberg, J. Lipsick, and M. Perl. 1979. Flavokinase and FAD synthetase from Bacillus subtilis specific for reduced flavins. J. Biol. Chem. 254:9551-9557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kedlaya, I., M. B. Ing, and S. S. Wong. 2001. Rhodococcus equi infections in immunocompetent hosts: case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:E39-E46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lampe, D. J., M. E. Churchill, and H. M. Robertson. 1996. A purified mariner transposase is sufficient to mediate transposition in vitro. EMBO J. 15:5470-5479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lampe, D. J., T. E. Grant, and H. M. Robertson. 1998. Factors affecting transposition of the Himar1 mariner transposon in vitro. Genetics 149:179-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levine, M. M., D. Herrington, J. R. Murphy, J. G. Morris, G. Losonsky, B. Tall, A. A. Lindberg, S. Svenson, S. Baqar, M. F. Edwards, et al. 1987. Safety, infectivity, immunogenicity, and in vivo stability of two attenuated auxotrophic mutant strains of Salmonella typhi, 541Ty and 543Ty, as live oral vaccines in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 79:888-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madarame, H., S. Takai, C. Matsumoto, K. Minamiyama, Y. Sasaki, S. Tsubaki, Y. Hasegawa, and A. Nakane. 1997. Virulent and avirulent Rhodococcus equi infection in T-cell deficient athymic nude mice: pathologic, bacteriologic and immunologic responses. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 17:251-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangan, M. W., and W. G. Meijer. 2001. Random insertion mutagenesis of the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi using transposomes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205:243-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mills, M., and S. M. Payne. 1995. Genetics and regulation of heme iron transport in Shigella dysenteriae and detection of an analogous system in Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 177:3004-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosser, D. M., and M. K. Hondalus. 1996. Rhodococcus equi: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Trends Microbiol. 4:29-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakazawa, M., M. Kubo, C. Sugimoto, and Y. Isayama. 1983. Serogrouping of Rhodococcus equi. Microbiol. Immunol. 27:837-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelicic, V., M. Jackson, J. M. Reyrat, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., B. Gicquel, and C. Guilhot. 1997. Efficient allelic exchange and transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10955-10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penfold, R. J., and J. M. Pemberton. 1991. A gene from the photosynthetic gene cluster of Rhodobacter sphaeroides induces trans suppression of bacteriochlorophyll and carotenoid levels in R. sphaeroides and R. capsulatus. Curr. Microbiol. 23:259-263. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plasterk, R. H., Z. Izsvak, and Z. Ivics. 1999. Resident aliens: the Tc1/mariner superfamily of transposable elements. Trends Genet. 15:326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prescott, J. F. 1981. Capsular serotypes of Corynebacterium equi. Can. J. Comp. Med. 45:130-134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puech, V., C. Guilhot, E. Perez, M. Tropis, L. Y. Armitige, B. Gicquel, and M. Daffe. 2002. Evidence for a partial redundancy of the fibronectin-binding proteins for the transfer of mycoloyl residues onto the cell wall arabinogalactan termini of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1109-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowland, S. J., and K. G. Dyke. 1990. Tn552, a novel transposable element from Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 4:961-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin, E. J., B. J. Akerley, V. N. Novik, D. J. Lampe, R. N. Husson, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1999. In vivo transposition of mariner-based elements in enteric bacteria and mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1645-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandmann, G. 1994. Carotenoid biosynthesis in microorganisms and plants. Eur. J. Biochem. 223:7-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sassetti, C. M., D. H. Boyd, and E. J. Rubin. 2001. Comprehensive identification of conditionally essential genes in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:12712-12717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shea, J. E., M. Hensel, C. Gleeson, and D. W. Holden. 1996. Identification of a virulence locus encoding a second type III secretion system in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2593-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stocker, B. A., S. K. Hoiseth, and B. P. Smith. 1983. Aromatic-dependent “Salmonella sp.” as live vaccine in mice and calves. Dev. Biol. Stand. 53:47-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takai, S. 1997. Epidemiology of Rhodococcus equi infections: a review. Vet. Microbiol. 56:167-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takai, S., S. A. Hines, T. Sekizaki, V. M. Nicholson, D. A. Alperin, M. Osaki, D. Takamatsu, M. Nakamura, K. Suzuki, N. Ogino, T. Kakuda, H. Dan, and J. F. Prescott. 2000. DNA sequence and comparison of virulence plasmids from Rhodococcus equi ATCC 33701 and 103. Infect. Immun. 68:6840-6847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takai, S., Y. Imai, N. Fukunaga, Y. Uchida, K. Kamisawa, Y. Sasaki, S. Tsubaki, and T. Sekizaki. 1995. Identification of virulence-associated antigens and plasmids in Rhodococcus equi from patients with AIDS. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1306-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takai, S., H. Madarame, C. Matsumoto, M. Inoue, Y. Sasaki, Y. Hasegawa, S. Tsubaki, and A. Nakane. 1995. Pathogenesis of Rhodococcus equi infection in mice: roles of virulence plasmids and granulomagenic activity of bacteria. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 11:181-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takai, S., T. Sekizaki, T. Ozawa, T. Sugawara, Y. Watanabe, and S. Tsubaki. 1991. Association between a large plasmid and 15- to 17-kilodalton antigens in virulent Rhodococcus equi. Infect. Immun. 59:4056-4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tkachuk-Saad, O., and J. Prescott. 1991. Rhodococcus equi plasmids: isolation and partial characterization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2696-2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuveson, R. W., R. A. Larson, and J. Kagan. 1988. Role of cloned carotenoid genes expressed in Escherichia coli in protecting against inactivation by near-UV light and specific phototoxic molecules. J. Bacteriol. 170:4675-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wada, R., M. Kamada, T. Anzai, A. Nakanishi, T. Kanemaru, S. Takai, and S. Tsubaki. 1997. Pathogenicity and virulence of Rhodococcus equi in foals following intratracheal challenge. Vet. Microbiol. 56:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu, W., M. A. Rould, S. Jun, C. Desplan, and C. O. Pabo. 1995. Crystal structure of a paired domain-DNA complex at 2.5 A resolution reveals structural basis for Pax developmental mutations. Cell 80:639-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]