Abstract

We recently demonstrated that caspase-3 is important for apoptosis during spontaneous involution of the corpus luteum (CL). These studies tested if prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) or FAS regulated luteal regression, utilize a caspase-3 dependent pathway to execute luteal cell apoptosis, and if the two receptors work via independent or potentially shared intracellular signaling components/pathways to activate caspase-3. Wild-type (WT) or caspase-3 deficient female mice, 25–26 days old, were given 10 IU equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) intraperitoneally (IP) followed by 10 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) IP 46 h later to synchronize ovulation. The animals were then injected with IgG (2 micrograms, i.v.), the FAS-activating antibody Jo2 (2 micrograms, i.v.), or PGF2α (10 micrograms, i.p.) at 24 or 48 h post-ovulation. Ovaries from each group were collected 8 h later for assessment of active caspase-3 enzyme and apoptosis (measured by the TUNEL assay) in the CL. Regardless of genotype or treatment, CL in ovaries collected from mice injected 24 h after ovulation showed no evidence of active caspase-3 or apoptosis. However, PGF2α or Jo2 at 48 h post-ovulation and collected 8 h later induced caspase-3 activation in 13.2 ± 1.8% and 13.7 ± 2.2 % of the cells, respectively and resulted in 16.35 ± 0.7% (PGF2α) and 14.3 ± 2.5% TUNEL-positive cells when compared to 1.48 ± 0.8% of cells CL in IgG treated controls. In contrast, CL in ovaries collected from caspase-3 deficient mice whether treated with PGF2α , Jo2, or control IgG at 48 h post-ovulation showed little evidence of active caspase-3 or apoptosis. CL of WT mice treated with Jo2 at 48 h post-ovulation had an 8-fold increase in the activity of caspase-8, an activator of caspase-3 that is coupled to the FAS death receptor. Somewhat unexpectedly, however, treatment of WT mice with PGF2α at 48 h post-ovulation resulted in a 22-fold increase in caspase-8 activity in the CL, despite the fact that the receptor for PGF2α has not been shown to be directly coupled to caspase-8 recruitment and activation. We hypothesize that PGF2α initiates luteolysis in vivo, at least in part, by increasing the bioactivity or bioavailability of cytokines, such as FasL and that multiple endocrine factors work in concert to activate caspase-3-driven apoptosis during luteolysis.

Background

Prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) has been implicated as a luteolysin in a number of mammalian species [1-3]. However, the exact mechanism(s) by which PGF2α elicits its response in the corpus luteum (CL) remains unclear. Results from previous studies have implicated so-called death receptor-activating cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and Fas ligand (FasL), as being important mediators of PGF2α-initiated luteolysis [4-6]. Unfortunately, since the vast majority of evidence supporting a role for cytokines in luteal regression has been derived from in vitro studies of dispersed cells in culture [5,7-14], it is currently unknown if PGF2α modulates death receptor-coupled signaling pathways in the CL in vivo.

At least 29 TNF receptor super family members have been identified in the human [15] some of which have been deemed death receptors either by their action or because they contain the highly homologous amino acid sequence corresponding to death domain (DD) [15,16]. The FAS/FasL system was chosen for study herein because FAS is recognized as a death receptor and indirect evidence suggests that it plays a significant role in luteal regression. For example, FAS immunostaining is observed in human granulosa-lutein cells during the early luteal phase, and progressively intensifies during the mid-luteal phase through the late luteal phase [17]. This expression pattern is also observed in the CL of mice [18] and rats [19,20]. In keeping with the proposal that FAS plays a role in luteolysis, in vitro studies have shown that FasL or FAS-activating antibodies induce luteal cell death in the human [10], mouse [5,18], rat [19,20] and cow [21]. Moreover, limited in vivo work has demonstrated that intravenous or intraperitoneal administration of FAS-activating antibody causes luteolysis in the mouse [18].

Additional support for a functional role of FAS in luteal regression has been derived from experiments with homozygous lpr mice, which have non-functional or minimally-functional FAS [22]. The CL of these mice undergo regression, but at irregular intervals [18]. Similarly, homozygous gld mice, which lack expression of functional FasL [22], have an irregular luteal phase similar to that observed in lpr/lpr mice [18]. Unfortunately, no work was done to characterize potential apoptosis defects in the CL of these mutants, and thus the basis for the irregular cyclicity remains unknown. Collectively these results suggest that FAS-mediated events are critical to timely progression of the normal estrous cycle, and perhaps to luteal regression, in the adult murine ovary.

Thus it is conceivable that some level of cross-talk occurs between PGF2α-initiated events and death receptor function during the tissue involution process of the CL. Mechanistically, this would likely involve the activation of caspases, a family of aspartic acid-specific cysteine proteases that serve as both initiators (e.g., caspase-8) and executioners (e.g., caspase-3) of apoptosis in vertebrates [23]. Indeed, we have recently shown using a synchronized ovulation mouse model that activation of caspase-3 is required for structural involution of the CL [24]. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that PGF2α-induced luteal regression in vivo is mediated through indirect mechanisms involving death receptor-coupled caspase-8 activation followed by a caspase-3-dependent pathway of apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type (WT) and caspase-3-deficient female mice (congenic C57BL/6) were generated by mating heterozygous male and female mice [25]. Female mice were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail-snip genomic DNA using specific primers [25]. Timed ovulation was induced in all experiments at day 25–26 postpartum by intraperitoneal injection of mice with 10 IU of eCG; (Professional Compounding Centers of America, Houston, TX) followed by 10 IU hCG; (Serono Laboratories, Randolph, MA) 46 h later [24]. This regime induces superovulation at approximately 10 hours post hCG with development of 8 to 10 CL per ovary. Peak progesterone synthesis occurs at approximately 30 hours post ovulation and levels fall back to preovulatory levels by approximately 60 hours (unpublished). All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and were performed in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

In vivo studies of luteal regression

In these experiments, gonadotropin-synchronized mice (wild-type or caspase-3-null) were injected at 24 or 48 h post-ovulation with IgG (2 μg/mouse, i.v.; a non-activating Anti-FAS antibody; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), the hamster monoclonal anti-mouse FAS-activating antibody Jo2 (2 μg/mouse, i.v.; PharMingen, San Diego, CA) or PGF2α (10 μg/mouse, i.p.; Lutalyse, Pharmacia-Upjohn Co., Kalamazoo, MI). Ovaries and blood were then collected at 8 h post-injection (n = 3 mice per genotype per treatment group). In some experiments, ovaries were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, serially sectioned (6 μm) and mounted in order on glass microscope slides. Ovarian mid-sagittal sections were used for immunohistochemical analysis of active caspase-3 (see below) or in situ analysis of DNA fragmentation by TUNEL (see below). In other experiments, CL were homogenized and assessed for caspase-8 activity (see below). Serum was separated from blood samples and stored at -80 C until analysis for progesterone concentrations (see below).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for the presence of cleaved ("active") caspase-3, as previously described [9,24,26,27] using a 1:3,000 dilution of a rabbit polyclonal antibody (CM1; IDUN Pharmaceuticals Inc., La Jolla, CA) that preferentially recognizes cleaved caspase-3 [9,24,26,27]. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and analyzed by light microscopy. Cells exhibiting red-brown cytoplasmic staining from the colorimetric reaction were considered positive for active caspase-3. Negative controls (reactions lacking primary antibody) yielded no reaction product (data not shown). Similarly, ovarian tissue samples from caspase-3 deficient mice exhibited minimal or no immunostaining (data not shown; see [24,26]), consistent with the fact that CM1 recognizes principally caspase-3 in addition to low cross-reactivity with processed ("active") caspase-7 [27]. Sections of ovaries from WT and caspase-3 deficient mice were always processed in parallel within the same assay. For quantitative comparisons, the number of caspase-3 positive cells was determined by counting CM-1 reactive cells in 3 fields of view (X600) per CL in three separate CL from each of 3 different mice per genotype per treatment group without knowledge of treatment.

In addition, samples from the two groups were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis of FAS protein as per the manufacturer's instructions with slight modifications as listed below. Paraffin sections were subjected to microwave on high power for 10 minutes in sodium acetate, pH6, for antigen retrieval. Sections were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal FAS antibody (1:50; SC-1024; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The secondary antibody, peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was applied at a dilution of 1:200. The sections were then stained with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) to identify FAS positive cells. Controls included sections treated in the same manner but incubated with normal rabbit serum instead of primary antibody. All immunohistochemical staining for any given antibody was done on all sections at the same time under the same conditions.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL)

The occurrence of apoptosis in luteal and ovarian sections was assessed by monitoring the presence of DNA fragmentation in situ, as described previously [28]. Slides were analyzed by light microscopy after light counterstaining with hematoxylin. Cells exhibiting dark brown nuclear staining from the colorimetric reaction were considered positive for DNA fragmentation. Negative controls, lacking the labeling enzyme, yielded no reaction product (data not shown). Sections of ovaries from WT and caspase-3 deficient mice were processed for TUNEL in parallel within the same assay. The percent of apoptotic cells was determined by counting TUNEL-positive cells out of the total number of cells per three fields of view (X600) in each of three CL from each of 3 different mice per genotype per treatment group.

Caspase-8 activity assay

Ovaries were removed 8 h post-treatment with IgG, Jo2, or PGF2α and CL were dissected out using a dissecting microscope. All CL from an individual animal were pooled and homogenized in lysis buffer from the ApoAlert Caspase-8 Colorimetric Assay Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The protein content was determined using the DC protein determination assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Samples were diluted to 2 μg protein/ml with dilution buffer supplied in the kit. Fifty μl of each diluted sample (100 ng protein/sample) was then incubated with 200 μM IETD-pNA substrate for 2 h at 37 C in the dark, and the reaction product was determined by reading the absorbance at 405 nm.

Serum hormone analysis

Progesterone levels were measured in serum according to the manufacturer's instructions using a direct solid phase enzyme-immunoassay (DRG Progesterone ELISA kit; ALPCO, Windham, NH), as previously validated in our laboratory [24].

Data Presentation and Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was independently replicated three times with different mice in each experiment. Qualitative data shown are representative of results obtained in the replicate experiments. Quantitative data (mean ± SEM) were analyzed by either Students t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan's New Multiple Range test when differences were observed. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Caspase-3 is required for apoptosis in CL following treatment with Jo2 or PGF2α

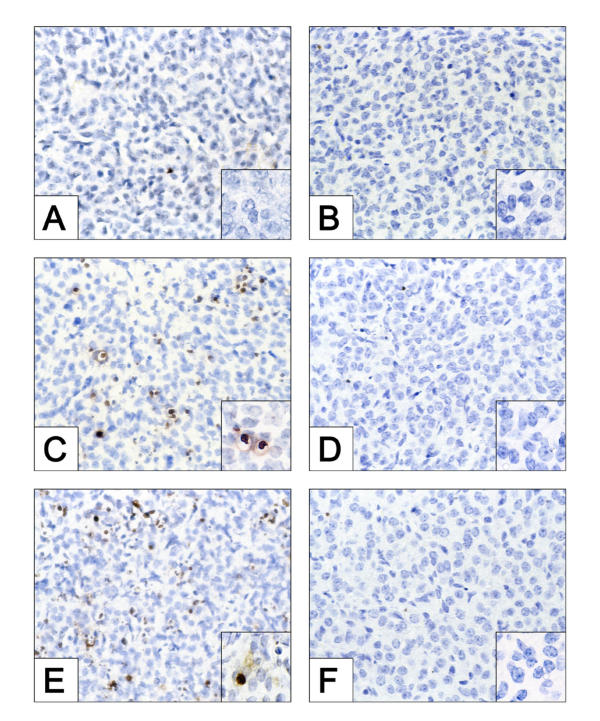

There was no evidence of TUNEL-positive cells in the CL of ovaries collected from WT or caspase-3-null mice following treatment at 24 h post-ovulation with IgG, FAS-activating antibody (Jo2) or PGF2α (data not shown). The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in CL of ovaries collected from WT mice following IgG injection at 48 h post-ovulation was 1.48 ± 0.8% (Fig. 1A). By comparison, the CL in ovaries collected from WT mice treated with Jo2 (Fig. 1C) or PGF2α (Fig. 1E) at 48 h post-ovulation exhibited a 10-fold or greater increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells per field of view (Jo2: 14.3 ± 2.5%; PGF2α: 16.35 ± 0.7%; P < 0.05 for both treatments versus IgG controls). In striking contrast to the results with WT mice, there was no significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in CL derived from caspase-3 deficient female mice treated at 48 h post-ovulation with Jo2 (Fig. 1D; 0.32 ± 0.17) or PGF2α (Fig. 1F; 0.22 ± 0.08) when compared with IgG-treated controls (Fig. 1B; 0.06 ± .003).

Figure 1.

Histochemical assessment of apoptosis in CL derived from WT and caspase-3-null mice following treatment with IgG, Jo2 or PGF2α, each administered at 48 h post-ovulation. The ovaries were harvested 8 h post-injection. The data shown depict the incidence of apoptotic (TUNEL-positive, brown staining) cells in CL of ovaries derived from WT (A, C, and E) and caspase-3 deficient mice (B, D, and F) following injection with IgG (A, B), Jo2 (C, D) or PGF2α (E, F). Original magnifications, × 600. The insets represent a higher magnification (× 1000), demonstrating the presence or absence of TUNEL positive cells. The photomicrographs shown are representative of similar results obtained in at least three independent experiments.

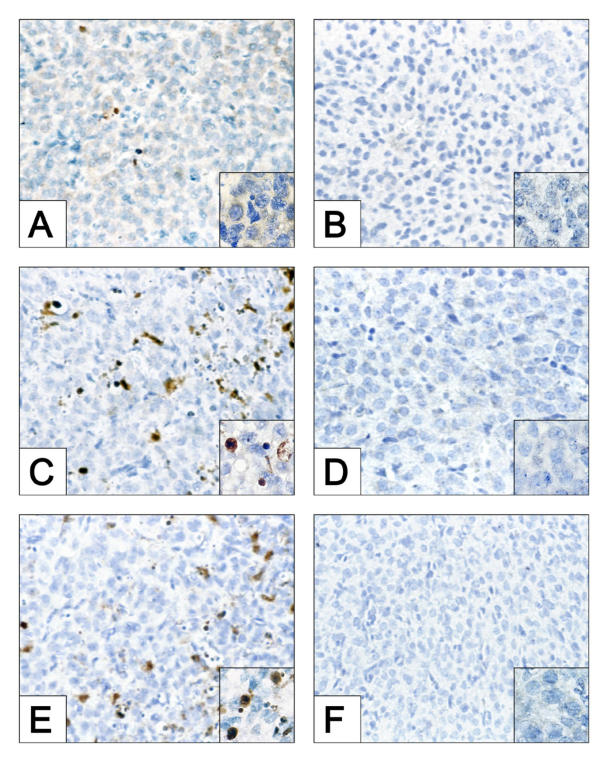

Jo2 or PGF2α increases active caspase-3 enzyme levels in CL of WT mice

There was no evidence of CM1-positive cells in the CL of ovaries collected from WT or caspase-3 deficient mice following treatment at 24 h post-ovulation with IgG, FAS-activating antibody (Jo2) or PGF2α (data not shown). The percentage of CM1-positive cells per field of view in CL of ovaries collected from WT mice following IgG injection at 48 h post-ovulation was low (1.3 ± 0.3%; Fig. 2A). By comparison, the CL in ovaries collected from WT mice treated with Jo2 (Fig. 2C) or PGF2α (Fig. 2E) at 48 h post-ovulation exhibited a 10-fold or greater increase in the percentage of CM1-positive cells per field of view (Jo2: 13.7 ± 2.2%; PGF2α: 13.2 ± 1.8%; P < 0.05 for both treatments versus IgG controls). As anticipated, there was no evidence of CM1-positive cells in CL derived from caspase-3 deficient female mice treated at 48 h post-ovulation with IgG (Fig. 2B), Jo2 (Fig. 2D) or PGF2α (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Detection of active caspase-3 in CL derived from WT and caspase-3-deficient mice following treatment with IgG, Jo2 or PGF2α. The presence of active caspase-3 was evaluated by immunohistochemistry using CM-1 antibody in sections of CL derived from WT or caspase-3-deficient mice 8 h following injection at 48 h post ovulation with IgG (A and B), Jo2 (C and D) or PGF2α (E and F). Original magnification: × 600. The insets represent a high magnification (original magnification × 1000) demonstrating the presence or absence of CM-1 positive cells (dark brown reaction). Medial sections were obtained from CL from three independent mice for analysis. Photomicrographs shown are representative of identical results in at least three separate experiments.

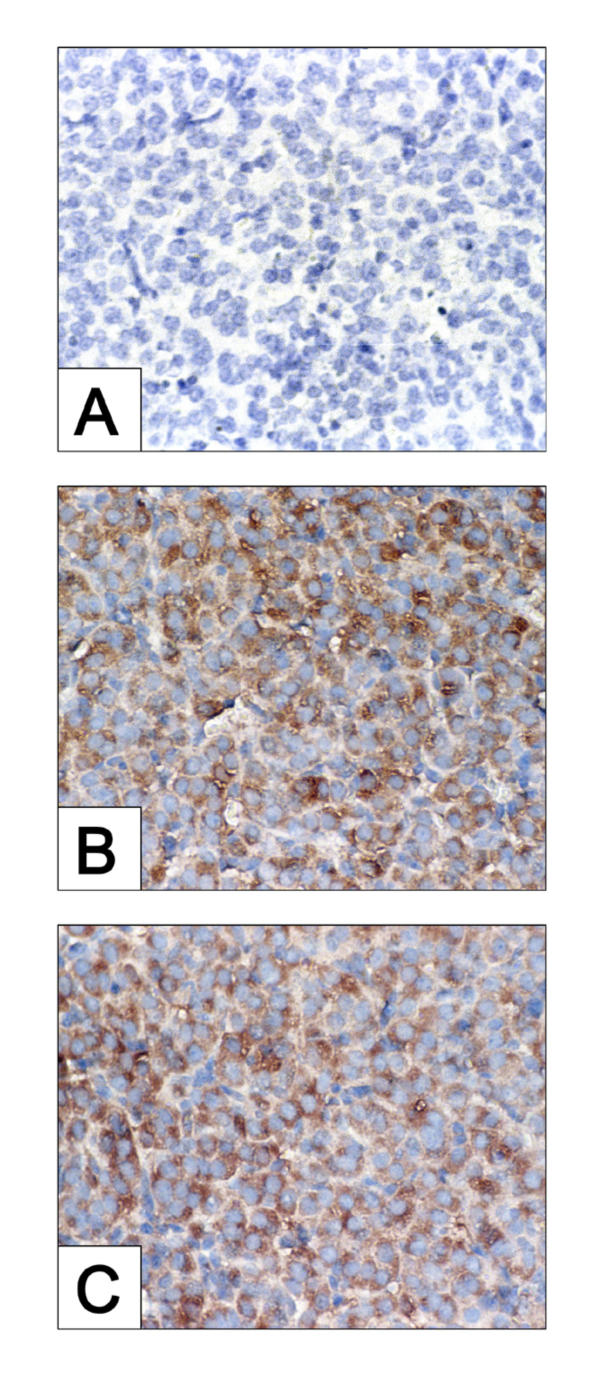

Immunohistochemical detection of FAS in WT and caspase-3 deficient mice

To rule out the possibility that the lack of effect of either Jo2 or PGF2α injected at 24 h post-ovulation was due to the lack of FAS expression in the CL of either WT or caspase-3 deficient mice, ovarian sections from both groups were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis of FAS protein. FAS was evident in luteal tissue of ovaries collected from both WT (Fig. 3B) and caspase-3-null (Fig. 3C) mice at 24 h post-ovulation.

Figure 3.

Histochemical assessment of FAS in CL derived from WT and caspase-3-deficient mice following treatment with IgG, Jo2 or PGF2α. administered 24 h post ovulation and ovaries harvested 8 h post injection. Panel represents a photomicrograph of a CL section derived from WT mouse used as a negative control (no primary antibody). Panel B and C are photomicrographs of CL sections derived from WT and caspase-3-deficient mice (respectively) probed with anti-FAS antibody. Original magnification for panels A, B and C × 600.

Serum levels of progesterone in caspase-3 deficient versus WT mice

There was no significant difference in the levels of progesterone in WT mice at 8 hours following injection with IgG (4.14 ± 1.09 ng/ml), Jo2 (4.90 ± 2.26 ng/ml), or PGF2α (4.66 ± 1.08 ng/ml) at 24 hours. In addition, no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the levels of progesterone was observed in WT versus caspase-3-null (ko) mice at 8 h after injection with IgG 2.76 ± 1.26, Jo2 (wt, 1.25 ± 0.34; ko 1.49 ± 0.63) or PGF2α (wt, 2.7 ± 0.8; ko, 3.7 ± 0.31) at the 48 h post-ovulation time-points.

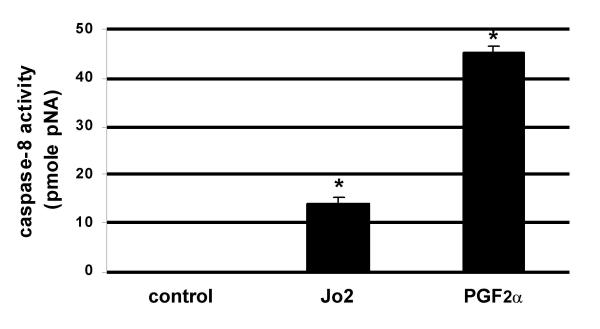

Caspase-8 activity

In a final set of experiments, the level of caspase-8 activity was determined in CL isolated from ovaries collected from WT mice 8 h following injection with IgG, Jo2 or PGF2α, at 48 h post-ovulation. Treatment with Jo2 resulted in an 8-fold increase (P < 0.04) in caspase-8 activity over the IgG treated controls (Fig. 4). In addition, CL of PGF2α-treated mice had a 22-fold increase (P < 0.0003) in caspase-8 activity over controls (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of Caspase-8 activity in CL in response to IgG, Jo2 or PGF2α in vivo. The level of caspase-8 activity was determined in CL isolated from ovaries collected from WT mice 8 h following injection IgG (2 μg/IV), Jo2 (2 μg/IV) or PGF2α (10 μg/IP). The asterisk (*) represent differences from the control P < 0.05. The experiment was replicated three separate times (n = 3) with different groups of mice.

Discussion

Prostaglandin F2α has long been proposed to disrupt progesterone synthesis, decrease blood flow, increase stress-related signaling, and induce cell death in the CL [2,3]. However, that PGF2α serves as a sole direct regulator of all aspects of luteal regression remains debatable, due in large part to discordant data resulting from species-specific differences in the control of CL function or from studies using in vivo versus in vitro approaches. For example, administration of PGF2α in vivo results in a decline in serum progesterone concentrations and an induction of luteal cell apoptosis in a number of species [29-33]. In contrast, treatment with PGF2α in vitro decreases gonadotropin-stimulated progesterone production in cultured rat, ovine, bovine [34-36] and human [37-40] luteal cells, but does not effect cell numbers or viability [35,41]. The loss of pro-apoptotic effects of PGF2α following ex vivo removal and chemical dispersal of the CL suggest that either other endocrine factors or cell-to-cell contact is required for PGF2α to kill luteal cells. While interaction between endothelial cells and steroidogenic luteal cells is probably important, recent data support the former possibility as well in that key roles for death receptor ligands, such as FasL and TNFα, in PGF2α-initiated luteolysis have been proposed [5,7,18-20,42]. Careful consideration should also be given to the role of PGF2α as a luteolytic agent in the mouse. Although it is arguably a primary luteolysin in a number of species and may serve as a secondary luteolysin in the rat, its role as a primary or secondary luteolytic agent in the mouse is uncertain. The PGF2α receptor mutant mouse appears to have a normal length estrous cycle, however luteal regression fails to occur during pregnancy [43]. It is not readily clear if the functional and structural components differ in the PGF2α receptor mutant as are described in the caspase-3 mutant mice. Of course it is also possible that there are redundant mechanisms which may serve to propagate the luteolytic signal during the estrous cycle in the absence of a PGF2α receptor.

To more easily study the events underlying the functional and structural components of luteal regression, which are temporally distinct, we have utilized the gonadotropin-synchronized luteal phase mouse model. In this model, we have found that circulating levels of progesterone peak at 30 h post-ovulation and precipitously decline to pre-luteal phase levels by 60 h after ovulation [24]. Structural involution of the CL occurs via caspase-3-mediated apoptosis around 48 h post-ovulation, as evidenced by a dramatic increase in TUNEL positive cells concomitant with the rapid decline in progesterone secretion [24]. The requirement for caspase-3, determined by the use of gene knockout mice, is consistent with reports that this executioner of apoptosis is expressed in the CL of many species, including the human, bovine, rat and mouse [24,44-46]. Moreover, caspase-3-like activity is up-regulated during luteal regression or luteal cell death [9,44,47]. Interestingly, however, whereas the levels of serum progesterone decline in caspase-3-null mice similar to their wild-type siblings during luteolysis, structural involution of the CL is suspended for at least 4 d in the mutant animals [24]. This study provided strong evidence for caspase-3 being paramount to structural involution but not loss of function (decreased progesterone) of the CL.

Using this ovulation-synchronized mouse model, in the present study we found that administration of PGF2α to WT female mice or their mutant siblings (caspase-3 deficient) at 24 or 48 h post-ovulation had no effect on progesterone levels versus controls. However, administration of PGF2α at 48 h post-ovulation resulted in a dramatic acceleration in the onset of apoptosis when compared to CL in untreated controls. This effect was mirrored by a proportional increase in the incidence of CM1 (active caspase-3)-positive cells in the CL, consistent with the hypothesis that this enzyme is important for cell death during structural involution of the CL [24]. These findings were extended by demonstrating that the CL from caspase-3 deficient mice were resistant to apoptosis induced by PGF2α exposure in vivo when compared to CL of WT type siblings treated in parallel. These data unequivocally demonstrate that caspase-3 is a required mediator of PGF2α-induced luteolysis.

Of interest, comparable results were obtained following injection of wild-type and caspase-3 deficient mice at 48 h post-ovulation with Jo2 antibody, an approach used routinely to activate the FAS death receptor in vivo [48,49]. The concentration of Jo2 used herein the present study has been shown to be sublethal [48]. The lack of a pro-apoptotic effect of Jo2, or for that matter of PGF2α, when injected at 24 h post-ovulation could not be attributed to lack of FAS since the receptor was present in CL derived from all treatment groups regardless of genotype. Of further interest, both Jo2 and PGF2α induced a significant increase in caspase-8 activity in CL homogenates. While FAS-mediated signaling clearly involves recruitment and activation of caspase-8 in all cell types analyzed to date [50], the finding that activity of this enzyme in the CL was so dramatically induced by PGF2α in vivo was a surprise. Sequence analysis indicates that the cloned receptor for PGF2α [51,52] does not contain a death-domain (DD), the structural motif found in death receptors that are capable of activating caspase-8 [50]. Therefore, we can only deduce that the ability of PGF2α to increase caspase-8 activity is indirectly due to its local modulation of death receptor activation in the CL.

Such a concept would be in keeping with studies of estrous cyclicity in mice lacking functional FAS [18], FasL [18] or TNF receptors [53]. In all three of these mutant mouse lines, luteal phase defects and/or aberrant estrous cycles have been reported. While such findings lend support to the importance of death receptor signaling in normal luteal regression, the disrupted follicular dynamics and ovarian function in these mutants also hindered our attempts to examine lpr/lpr mice (Jackson Laboratories) for defects in either PGF2α-induced luteal regression or luteal cell apoptosis. In our hands the lpr/lpr mice failed to consistently respond to gonadotropin stimulation as did their wild type siblings (data not shown) lending further support to their irregular cyclicity reported previously [18]. Nonetheless, in light of the data presented, we conclude that PGF2α, along with pro-apoptotic cytokines activated in response to PGF2α, work in concert to orchestrate luteal demise in vivo via a caspase-3-dependent pathway of apoptosis. Our current efforts are directed at determining the mechanism(s) by which PGF2α up-regulates the activity of death receptor function in the CL, as well as which specific death ligand-receptor family members are expressed, and modulated by PGF2α, in the CL.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Anu Srinivasan (IDUN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., La Jolla, CA) for generously providing the CM1 antibody, and we are indebted to Mr. Sam Riley (Massachusetts General Hospital) for outstanding technical assistance with the image analysis and data presentation.

*This work was supported by NIH grant R01-HD35934 (B.R.R.) and Vincent Memorial Research Funds (B.R.R., J.L.T.). This work was conducted while S.F.C. was a Doctoral candidate supported by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) of the Brazilian Government Foundation, and while T.M. was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow supported by the Finnish Foundation for Pediatric Research and the Finnish Cultural Foundation. J.K.P. completed this work while he was a Lalor Foundation Fellow. R.A.F. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. J.L.T. is an Investigator at the Steven and Michele Kirsch Foundation.

Contributor Information

Silvia F Carambula, Email: silviafc@hcv.ufsm.br.

James K Pru, Email: jpru@partners.org.

Maureen P Lynch, Email: mplynch@partners.org.

Tiina Matikainen, Email: tiina.matikainen@pp.inet.fi.

Paulo Bayard D Gonçalves, Email: bayard@hcv.ufsm.br.

Richard A Flavell, Email: richard.flavell@yale.edu.

Jonathan L Tilly, Email: jtilly@partners.org.

Bo R Rueda, Email: brueda@partners.org.

References

- Niswender GD. Molecular control of luteal secretion of progesterone. Reproduction. 2002;123:333–339. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1230333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender GD, Juengel JL, Silva PJ, Rollyson MK, McIntush EW. Mechanisms controlling the function and life span of the corpus luteum. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1–29. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken JA, Custer EE, Lamsa JC. Luteolysis: a neuroendocrine-mediated event. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:263–323. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate JL, Landis Keyes P. Immune cells in the corpus luteum: friends or foes? Reproduction. 2001;122:665–676. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk SM, Harman RM, Huber SC, Cowan RG. Responsiveness of mouse corpora luteal cells to Fas antigen (CD95)-mediated apoptosis. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:49–56. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terranova PF. Potential roles of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in follicular development, ovulation, and the life span of the corpus luteum. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 1997;14:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(96)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff MG, Petroff BK, Pate JL. Mechanisms of cytokine-induced death of cultured bovine luteal cells. Reproduction. 2001;121:753–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter J, Hendry IR, Ndjountche L, Obholz K, Pru JK, Davis JS, Rueda BR. Mediators of interferon gamma-initiated signaling in bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:1481–1486. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.5.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda BR, Hendry IR, Ndjountche L, Suter J, Davis JS. Stress-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the corpus luteum. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;164:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk SM, Cowan RG, Joshi SG, Henrikson KP. Fas antigen-mediated apoptosis in human granulosa/luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:279–287. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka M, Yasuda K, Fujiwara H, Kanzaki H, Mori T. Interactions between interferon gamma, tumour necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-1 in modulating progesterone and oestradiol production by human luteinized granulosa cells in culture. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:1361–1364. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka M, Yasuda K, Emi N, Fujiwara H, Iwai M, Takakura K, Kanzaki H, Mori T. Cytokine modulation of progesterone and estradiol secretion in cultures of luteinized human granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:254–258. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.1.1377705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyo DF, Pate JL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha alters bovine luteal cell synthetic capacity and viability. Endocrinology. 1992;130:854–860. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.2.1733731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara H, Ikuta K, Ozaki Y, Suzuki Y, Suzuki N, Sato T, Suzumori K. Gonadotropins and cytokines affect luteal function through control of apoptosis in human luteinized granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1620–1626. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.4.6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Tschopp J. The molecular architecture of the TNF superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEwan DJ. TNF receptor subtype signalling: Differences and cellular consequences. Cell Signal. 2002;14:477–492. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo H, Maruo T, Peng X, Mochizuki M. Immunological evidence for the expression of the Fas antigen in the infant and adult human ovary during follicular regression and atresia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2702–2710. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.7.8675599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamaki K, Yoshida H, Nishimura Y, Nishikawa S, Manabe N, Yonehara S. Involvement of Fas antigen in ovarian follicular atresia and luteolysis. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;47:11–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199705)47:1<11::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughton SA, Lareu RR, Bittles AH, Dharmarajan AM. Fas and Fas ligand messenger ribonucleic acid and protein expression in the rat corpus luteum during apoptosis-mediated luteolysis. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:797–804. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuranaga E, Kanuka H, Furuhata Y, Yonezawa T, Suzuki M, Nishihara M, Takahashi M. Requirement of the Fas ligand-expressing luteal immune cells for regression of corpus luteum. FEBS Lett. 2000;472:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pru JK, Hendry IR, Davis JS, BR R. Fas-mediated activation of the sphingomyelin pathway in bovine steroidogenic luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:198. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen PL, Eisenberg RA. Lpr and gld: single gene models of systemic autoimmunity and lymphoproliferative disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:243–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. Mechanisms of caspase activation and inhibition during apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2002;9:459–470. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carambula SF, Matikainen T, Lynch MP, Flavell RA, Goncalves PB, Tilly JL, Rueda BR. Caspase-3 is a pivotal mediator of apoptosis during regression of the ovarian corpus luteum. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1495–1501. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K, Zheng TS, Na S, Kuan C, Yang D, Karasuyama H, Rakic P, Flavell RA. Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;384:368–372. doi: 10.1038/384368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen T, Perez GI, Zheng TS, Kluzak TR, Rueda BR, Flavell RA, Tilly JL. Caspase-3 gene knockout defines cell lineage specificity for programmed cell death signaling in the ovary. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2468–2480. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan A, Roth KA, Sayers RO, Shindler KS, Wong AM, Fritz LC, Tomaselli KJ. In situ immunodetection of activated caspase-3 in apoptotic neurons in the developing nervous system. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:1004–1016. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda BR, Tilly KI, Hansen TR, Hoyer PB, Tilly JL. Expression of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in the bovine corpus luteum: Evidence supporting a role for oxidative stress in luteolysis. Endocrine. 1995;3:227–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02994448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengel JL, Haworth JD, Rollyson MK, Silva PJ, Sawyer HR, Niswender GD. Effect of dose of prostaglandin F2α on steroidogenic components and oligonucleosomes in ovine luteal tissue. Biology of Reproduction. 2000;62:1047–1051. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.4.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengel JL, Garverick HA, Johnson AL, Youngquist RS, Smith MF. Apoptosis during luteal regression in cattle. Endocrinology. 1993;132:249–254. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.1.8419126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda BR, Wegner JA, Marion SL, Wahlen DD, Hoyer PB. Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation in ovine luteal tissue associated with luteolysis: in vivo and in vitro analyses. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:305–312. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack JT, Friederichs MG, Limback SD, Greenwald GS. Apoptosis during spontaneous luteolysis in the cyclic golden hamster: biochemical and morphological evidence. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:255–260. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Wolf V, Dharmarajan AM, Feng Z, Bielke W, Saurer S, Friis R. Apoptosis-associated gene expression in the corpus luteum of the rat. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:739–746. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.3.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrard M, Leboulleux P, Hermier C. Role of prostaglandin F2alpha in modulation of LH-stimulated steroidogenesis in vitro in different types of rat and ewe corpora lutea. Prostaglandins. 1978;16:491–500. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(78)90179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate JL, Condon WA. Effects of prostaglandin F2 alpha on agonist-induced progesterone production in cultured bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 1984;31:427–435. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod31.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright K, Pang CY, Behrman HR. Luteal membrane binding of prostaglandin F2 alpha and sensitivity of corpora lutea to prostaglandin F2 alpha-induced luteolysis in pseudopregnant rats. Endocrinology. 1980;106:1333–1337. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-5-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abayasekara DR, Michael AE, Webley GE, Flint AP. Mode of action of prostaglandin F2 alpha in human luteinized granulosa cells: role of protein kinase C. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1993;97:81–91. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(93)90213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abayasekara DR, Jones PM, Persaud SJ, Michael AE, Flint AP. Prostaglandin F2 alpha activates protein kinase C in human ovarian cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1993;91:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(93)90254-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Wiltbank MC. Differential effects of prostaglandin F2alpha on in vitro luteinized bovine granulosa cells. Reproduction. 2001;122:245–253. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaananen JE, Tong BL, Vaananen CM, Chan IH, Yuen BH, Leung PC. Interaction of prostaglandin F2alpha and gonadotropin-releasing hormone on progesterone and estradiol production in human granulosa-luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:1346–1353. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.6.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate JL. Cellular components involved in luteolysis. J Anim Sci. 1994;72:1884–1890. doi: 10.2527/1994.7271884x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchio VA, Pru JK, Davis BS, Davis JS, Rueda BR, Townson DH. Secretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) by endothelial cells of the bovine corpus luteum: Regulation by cytokines but not prostaglandin F2 alpha. Endocrinology. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto Y, Yamasaki A, Segi E, Tsuboi K, Aze Y, Nishimura T, Oida H, Yoshida N, Tanaka T, Katsuyama M, Hasumoto K, Murata T, Hirata M, Ushikubi F, Negishi M, Ichikawa A, Narumiya S. Failure of parturition in mice lacking the prostaglandin F receptor. Science. 1997;277:681–683. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda BR, Hendry IR, Tilly JL, Hamernik DL. Accumulation of caspase-3 messenger ribonucleic acid and induction of caspase activity in the ovine corpus luteum following prostaglandin F2alpha treatment in vivo. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1087–1092. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.5.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone DL, Tsang BK. Caspase-3 in the rat ovary: localization and possible role in follicular atresia and luteal regression. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:1533–1539. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.6.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski S, Gascoyne RD, Zapata JM, Krajewska M, Kitada S, Chhanabhai M, Horsman D, Berean K, Piro LD, Fugier-Vivier I, Liu YJ, Wang HG, Reed JC. Immunolocalization of the ICE/Ced-3-family protease, CPP32 (Caspase-3), in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, chronic lymphocytic leukemias, and reactive lymph nodes. Blood. 1997;89:3817–3825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Dauffenbach LM, Yeh J. Mitochondria and caspases in induced apoptosis in human luteinized granulosa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:542–545. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T, Genestier L, Pinkoski MJ, Castro A, Nicholas S, Mogil R, Paris F, Fuks Z, Schuchman EH, Kolesnick RN, Green DR. Role of acidic sphingomyelinase in Fas/CD95-mediated cell death. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8657–8663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakinuma C, Takagaki K, Yatomi T, Nakamura N, Nagata S, Uemura A, Shibutani Y. Acute toxicity of an anti-Fas antibody in mice. Toxicol Pathol. 1999;27:412–420. doi: 10.1177/019262339902700404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius U, Schmitz I, Krammer PH. Molecular mechanisms of death-receptor-mediated apoptosis. Chembiochem. 2001;2:20–29. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010105)2:1<20::AID-CBIC20>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Hasumoto K, Namba T, Irie A, Katsuyama M, Negishi M, Kakizuka A, Narumiya S, Ichikawa A. Cloning and expression of a cDNA for mouse prostaglandin F receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1356–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake S, Gullberg H, Wahlqvist J, Sjogren AM, Kinhult A, Lind P, Hellstrom-Lindahl E, Stjernschantz J. Cloning of the rat and human prostaglandin F2 alpha receptors and the expression of the rat prostaglandin F2 alpha receptor. FEBS Lett. 1994;355:317–325. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roby KF, Son DS, Terranova PF. Alterations of events related to ovarian function in tumor necrosis factor receptor type I knockout mice. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1616–1621. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.6.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]