Abstract

Two dominant temperature-sensitive (DTS) lethal mutants of Drosophila melanogaster are Pros261 and Prosβ21, previously known as DTS5 and DTS7. Heterozygotes for either mutant die as pupae when raised at 29°, but are normally viable and fertile at 25°. Previous studies have identified these as missense mutations in the genes encoding the β6 and β2 subunits of the 20S proteasome, respectively. In an effort to isolate additional proteasome-related mutants a screen for dominant suppressors of Pros261 was carried out, resulting in the identification of Pros25SuDTS [originally called Su(DTS)], a missense mutation in the gene encoding the 20S proteasome α2 subunit. Pros25SuDTS acts in a dominant manner to rescue both Pros261 and Prosβ21 from their DTS lethal phenotypes. Using an in vivo protein degradation assay it was shown that this suppression occurs by counteracting the dominant-negative effect of the DTS mutant on proteasome activity. Pros25SuDTS is a recessive polyphasic lethal at ambient temperatures. The effects of these mutants on larval neuroblast mitosis were also examined. While Prosβ21 shows a modest increase in the number of defective mitotic figures, there were no defects seen with the other two mutants, other than slightly reduced mitotic indexes.

IN eukaryotes most regulated protein degradation is carried out via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Glickman and Ciechanover 2002). In this process, proteins are targeted for destruction by the covalent attachment of a multiubiquitin chain, whereupon they become substrates for a large proteolytic machine called the proteasome. The core of this 26S holoenzyme is a hollow barrel-shaped 20S particle made up of four stacked rings. The two inner rings are each composed of seven distinct β-type subunits (β1–β7) while the two outer rings are each made up of seven different α-type subunits (α1–α7). At each end of the 20S core is a 19S regulatory complex that acts as a gatekeeper, capturing, deubiquinylating, and unfolding tagged substrates and ushering them into the inner chamber of the 20S core where they are hydrolyzed into short peptides.

By controlling the rapid and irreversible turnover of key regulatory proteins, the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway plays important roles in a variety of biological processes, including cell cycle progression (Reed 2003), transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling (Kinyamu et al. 2005; Hegde and Upadhya 2006), memory and synaptic plasticity (DiAntonio and Hicke 2004), circadian rhythms (Naidoo et al. 1999), signal transduction (Ye and Fortini 2000), metabolic regulation (Hampton and Bhakta 1997), antigen processing (Kloetzel 2004), and programmed cell death (Friedman and Xue 2004). This pathway also carries out an important “housekeeping” function, by ridding cells of potentially harmful abnormal proteins that arise as the result of mutation, misfolding, or postsynthetic damage (Kostova and Wolf 2003).

One way to investigate the biological roles of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway is to use a mutational approach to disrupt proteasome function and to then assess the effects on the process of interest. Since this pathway is critically involved in so many cellular events most proteasome null mutants are lethals. Thus, the most useful alleles for manipulating proteasome function are hypomorphic (leaky) or conditional mutants. In Drosophila melanogaster, two such mutants are Pros261 and Prosβ21. These were isolated in a screen for dominant temperature-sensitive (DTS) lethal mutants and originally named DTS5 and DTS7 (Holden and Suzuki 1973). Subsequent study revealed that each mutation results in a single-amino-acid substitution in a 20S proteasome subunit (the β6 and β2 subunits, respectively) (Saville and Belote 1993; Smyth and Belote 1999). The phenotypes of both mutants are similar, with heterozygotes raised at 29° dying during the pupal stage with numerous defects including reduced abdominal histoblast proliferation and a failure of head eversion. At 25°, such flies develop normally and are fully viable and fertile. These two mutants exhibit strong synthetic lethality in that double heterozygotes die as early stage larvae at ≥22° (Smyth and Belote 1999). Genetic and biochemical evidence suggests that these mutants act in a dominant-negative manner to interfere with proteasome function (Saville and Belote 1993; Covi et al. 1999; Schweisguth 1999; Smyth and Belote 1999; Speese et al. 2003; K. Vitale and J. Belote, unpublished data). Null alleles of these loci are recessive, non-temperature-sensitive, early larval lethals (Smyth and Belote 1999).

The dominant temperature-sensitive nature of these mutants makes them useful for manipulating proteasome function in vivo (e.g., see Huang et al. 1995; Henchoz et al. 1996; Heriche et al. 2003). For example, by shifting the culture temperature of heterozygotes during development it is possible to disrupt proteasome function in a stage-specific manner. Because Pros261 and Prosβ21 act in a dominant-negative manner, it is also possible to target their effects to particular cells or tissues using the UAS/GAL4 binary system of Brand and Perrimon (1993). A number of UAS-Pros261 and UAS-Prosβ21 transgenic lines have been generated and used for this purpose (Schweisguth 1999; Belote and Fortier 2002; Chan et al. 2002; Khush et al. 2002; Speese et al. 2003; Shulman and Feany 2003; Tang et al. 2005). These transgenic lines provide a complementary approach to the use of proteasome inhibitors (Myung et al. 2001) to investigate the roles that proteasome-related proteolysis plays during development. This genetic approach has some advantages over the use of exogenous inhibitors, whose specific delivery only to the cells of interest is difficult.

In an effort to isolate additional useful proteasome mutants, a screen for dominant suppressors of the Pros261 mutant was carried out. It was hypothesized, on the basis of classic studies of suppression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (e.g., see Huffaker et al. 1987; Adams and Botstein 1989; Novick et al. 1989), that dominant extragenic suppressors of this conditional mutant, encoding a component of a multisubunit complex, might represent useful hypomorphic, conditional, or gain-of-function alleles of other proteasome components. Here we describe the isolation and genetic characterization of a dominant suppressor of both Pros261 and Prosβ21 and show that it is a mutant allele of Pros25, encoding the α2 subunit of the 20S proteasome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly culture:

D. melanogaster strains were cultured on standard media containing cornmeal, dextrose, sucrose, yeast, and agar. Stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center, and their descriptions are available on the FlyBase server (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu/). P-element transformation was done using standard procedures with w1118 as the host strain.

Isolation and mapping of the Su(DTS) mutant:

Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e males were fed for 24 hr on a solution containing 0.2 mg/ml of l-ethyl-1-nitrosourea (ENU; Sigma, St. Louis) in 2% sucrose. Following a 24-hr recovery period on standard, yeasted Drosophila medium, the males were mated to Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e virgin females (∼25 pairs/bottle). After a day at room temperature, bottles were placed at 29° and parents removed at day 7. Rare survivors were mated to Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e mates and progeny reared at 29° to confirm that the original survivor was not an “escaper.” Only lines that gave robust survival at 29° were kept for analysis. The Su(DTS) mutant was separated from the Pros261 allele by meiotic recombination and mapped using the multiply marked ru h th st cu sr es ca chromosome. A second meiotic recombination mapping experiment used the st ri pp chromosome. For the two mapping experiments, the third chromosome carrying the Su(DTS) mutant was made heterozygous over the multiply marked chromosome in females, which were then crossed to ru h th st cu sr es Pri ca/TM6B, Bri1 or st ri Ki pp males, respectively. Various recombinant males were then selected and tested for the ability to suppress the dominant temperature-sensitive lethality of Pros261 by mating them to Pros261 pb pp/TM3, Sb pp e virgins and raising the offspring at 29°. All recombinant chromosomes that carried Su(DTS) were homozygous lethal. The recessive lethal was therefore mapped by deficiency mapping using the following: Df(3R)by62, Df(3R)cu, Df(3R)M-Kxl, Df(3R)T-32, Df(3R)ry85, Df(3R)MRS, and Df(3R)red3l.

The Su(DTS) mutation was mapped more precisely using P-element-mediated site-specific male recombination (Chen et al. 1998). Females of genotype y w; CyO, H{P{Δ2-3}HoP2.1/Bc1 EgfrE1; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM3, Sb pp e were crossed to males of various P-element insertion lines to generate y w; CyO, H{P{Δ2-3}HoP2.1/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/P-element males. These were then individually crossed to st e virgin females and offspring were scored for st+ e and st e+ recombinants. Recombinant males were each tested first for the presence of the recessive lethal associated with Su(DTS) by crossing them to st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM3, Sb females. Once larvae were apparent, the recombinant males were then removed and tested for the presence of the dominant suppressor of DTS by mating them to Pros261 pb pp/TM3, Sb pp e and raising the offspring at 29°. The P elements used for mapping Su(DTS) included: P{PZ}srp[01549], P{lacW}Vha55[j2E9], P{PZ}svp[07842], P{PZ}l(3)09656[09656], P{PZ}l(3)rM060[rM060], P{PZ}tws[02414], and P{PZ}l(3)10615[10615]. In all cases, both phenotypes mapped to the same side of the P element.

General molecular procedures:

All standard molecular techniques were done essentially as described in Sambrook et al. (1989). Plasmid purification was done using the Wizard Plus Miniprep kit (Promega, Madison, WI). DNA sequencing was performed by the Syracuse University Biology Department Sequencing Facility (Syracuse, NY) or the BioResource Center at Cornell University (Ithaca, NY).

Cloning of the Pros25 gene:

Genomic DNA was extracted from non-Tubby third instar larvae from a cross of st ri pp Su(DTS) es ca/TM6B, Tb e ca males and females according to the method of Gloor and Engels (1992). Pros25 sequences were PCR amplified using the following primers: PROS25-5′-1, ATCAAATCACTGCATTTGCGG, and PROS25-3′-4, CTTAGCTTGTGGTAATCTTAGC, and ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) to give pGEM-T Easy/Pros25SuDTS. Clones from two independent PCR reactions were sequenced using the T7 and M13R primers corresponding to vector sequences and two internal primers, PROS25-5′-2, GAGATGATCTACAACCACATC, and PROS25-3′-3, GATCAGTAGGGAAACGCCAAA. To clone the Pros25 allele present on the unmutagenized chromosome, genomic DNA was extracted from non-Tubby larvae raised at 18° from a cross of Pros261/TM6B, Tb e ca males and females, and the Pros25 gene was PCR amplified and cloned as above to give pGEM-T Easy/Pros25+.

P-element transformation constructs:

A BAC clone (RPCI-98 28.I.14) containing the Pros25 genomic region was obtained from Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute (Hoskins et al. 2000) and DNA was prepared using a QIAGEN (Valencia, CA) plasmid midi-prep kit. The published sequence of this clone (accession no. AC007594) predicted a 5.7-kb KpnI–SalI fragment containing the Pros25 gene region. BAC DNA was therefore treated with these enzymes and the 5.7-kb fragment was gel purified and ligated into pBluescriptKS+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to obtain pBS/Pros25-5.7KS. A 2.0-kb KpnI–BamHI fragment from this clone was subcloned into pBluescriptKS+ to give pBS/Pros25-2.0KB. The 2.0-kb KpnI–BamHI fragment was then subcloned into the pW8 transformation vector to give pW8/Pros25-2.0KB. The construct was introduced into the genome by P-element transformation and several transgenic lines were obtained.

The inserts from pGEM-T Easy/Pros25+ and pGEM-T Easy/Pros25SuDTS were cut out with EcoRI and cloned into the pUAST vector to give pUAST/Pros25+ and pUAST/Pros25SuDTS, and multiple transgenic lines were obtained for each. Strains containing UAS-Pros261 or UAS-Prosβ21 transgenes are described in Belote and Fortier (2002). Creation of the UAS-Pros29 transgenic line is described in Ma (2001).

Cytology:

Metaphase figures were prepared according to the protocol of Gatti and Baker (1989). Brains from late third instar larvae raised at 29° were dissected in 0.7% saline, incubated in 0.5 × 10−5 m colchicine in 0.7% NaCl for 1 hr at room temperature, and placed in 0.5 m sodium citrate for 7 min. After fixing in methanol:acetic acid:dH2O (11:11:2) for 30–45 sec the brains were placed in a 5-μl drop of aceto-orcein stain (2% orcein in 45% acetic acid) on a siliconized coverslip and then squashed on a microscope slide. For observation of anaphase figures and determination of mitotic indexes, the colchicine and sodium citrate steps were omitted. Slides were examined with a Zeiss Axioplan phase contrast microscope using a 100× oil immersion objective. Mitotic indexes (MI) were calculated as the number of mitotic figures per microscope field. At least six slides were scored for each genotype, with the number of fields scanned per slide varying between 40 and 108, depending on the size of the brain squash.

Construction of heat-shock-inducible unstable and stable GFP reporter transgenes:

An unstable enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) reporter was made by fusing a portion of the Drosophila Notch protein containing its PEST degradation signal (i.e., the Notch-intracellular, Nintra, domain) to the C terminus of EGFP. First, a fragment of the Drosophila Notch gene, encoding the carboxy-terminal 178 amino acids of Notch, was PCR amplified from genomic DNA using primers BNIN, CGGATCCTCGAAGAATAGTGCAATAATGCAAACG, and NINN, GCGGCCGCGATATTCAACATACCAAATCATCCAGATCA, and ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) to give pGEM-T/NintraBN. The coding region of pEGFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was PCR amplified using primers BEGFP, GGATCCGAATTCGCCACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG, and GFPB, GGATCCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCCGAGAGTGATCCC, and ligated into pGEM-T Easy. The EGFP sequence was then cut out with BamHI and ligated into the BamHI site of pGEM-T/NintraBN to give pGEM-T/EGFP-Nintra. A clone with EGFP inserted in the correct orientation was digested with NotI and the 1.4-kb fragment was subcloned into pCaSpeR-hs (Thummel and Pirrotta 1992) to yield pCasper-hs/EGFP-Nintra. This was introduced into the genome by P-element-mediated germline transformation and several transgenic lines were established. One line, w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra,w+}15(X), which carries the transposon on the X chromosome, gave good heat-shock-inducible expression of EGFP-Nintra and was used for the experiments described here. As a control, a stable, heat-shock-inducible EGFP construct was made by subcloning the HincII/NotI restriction fragment of pEGFP into the HpaI/NotI sites of pCaSpeR-hs to give pCasper-hs/EGFP. One transgenic line, w; P{hs-EGFP, w+}12(3) was generated, which gave good heat-shock-inducible expression of EGFP.

In vivo monitoring of GFP stability:

To assess the degradation of EGFP-Nintra in the presence of dominant proteasome mutants, females of genotype w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra}15(X); P{w+mW.hs=GawB}ptc559.1 were crossed at 29° to the following males: w; P{UAS-Prosβ21, w+}2B(3), w: P{UAS-Pros261, w+}6A(3), w; P{UAS-Pros25+, w+}4A(2), w; P{UAS-Pros25SuDTS, w+}2A(2), w: P{UAS-Pros29, w+}1(2), w; P{UAS-lacZ, w+}(2), and w; P{UAS-Pros25SuDTS, w+}2A(2); P{UAS-Prosβ21, w+}2B(3). Late third instar larvae were placed in prewarmed small petri dishes containing grape juice/agar and heat-shocked by placing them in a 37° incubator for 30 min. The larvae were then transferred to a 29° dish and allowed to recover for 4 hr. Larvae were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 130 mm NaCl, 7 mm Na2HPO4, 3 mm NaH2PO4, pH 7.0) and the carcasses, with wing discs exposed, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (EM Sciences) in PBST (PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100) for 1 hr. After washing 3 × 20 min in PBST, the larvae were treated for 1 hr at 37° with RNase A (0.5 mg/ml in PBST) and then washed 3 × 20 min with PBST. They were then transferred to PBS containing 1 μg/ml TOPRO-3 DNA stain (Invitrogen, San Diego) for 30 min and washed briefly in PBS. The wing discs were then dissected and mounted in ProLong anti-fade mountant (Invitrogen). A Zeiss LSM5 Pascal confocal microscope was used for fluorescence imaging.

Structural analysis of the 20S proteasome:

Mutations were mapped onto the structure of the bovine 20S proteasome, Protein database code 1IRU (Unno et al. 2002), using the PyMOL molecular graphics system (http://www.pymol.org).

RESULTS

Isolation of a dominant suppressor of Pros261:

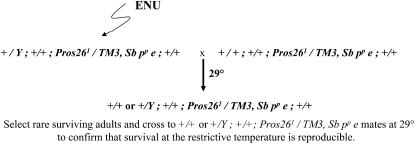

The Pros261 mutant is a highly penetrant DTS lethal that also acts as a recessive lethal at all temperatures (Holden and Suzuki 1973; Saville and Belote 1993). When heterozygotes are reared at 29°, very few, if any, survive to adulthood. In an effort to identify new genes that play roles in the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, a screen for dominant suppressors of the Pros261 DTS lethality was carried out (Figure 1). In this experiment, Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e males were fed ENU and mated to Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e females. The F1 were raised at 29°. In the absence of any new mutation, no survivors were expected. To estimate the number of F1 individuals being screened, control crosses were maintained at 25° and scored for survival of Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e offspring. Of ∼4000 Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e F1 individuals raised at 29°, ∼10 adult flies were recovered. Most of these were sick and sterile and could represent rare escapers that somehow avoided the usual lethality. The few fertile F1 adults were crossed to Pros261/TM3, Sb pp e mates and progeny were raised at 29° to see if the suppression of DTS lethality was heritable and reproducible. Three balanced stocks were established for further analysis. Although the design of this screen could have resulted in the isolation of suppressors of DTS on any of the chromosomes, all three mutants mapped to chromosome 3.

Figure 1.—

Crossing scheme for the mutant screen for suppressors of Pros261 DTS lethality.

Of the three DTS suppressor mutants, two were “pseudorevertants” that had picked up a loss-of-function mutation of Pros26. These were characterized by early larval lethality at 25° when the mutant chromosome was placed over either Pros261 or Df(3L)st-j7 (a deletion of the Pros26 gene region) and by the lack of any synthetic lethal interaction with Prosβ21. These suppressor mutants also could not be separated by recombination from the Pros261 gene present on the original mutagenized chromosome. One of these, Pros26rv10e, was further characterized molecularly by PCR amplifying and sequencing the Pros26 gene and, as expected, it was found to carry a newly induced mutation in the Pros26 coding region that presumably results in a null allele; i.e., it was a nonsense mutation at codon position 78. Such pseudorevertants are expected products of this screen since a newly induced null mutation in the original Pros261 allele would no longer act in a dominant-negative fashion.

One mutant line had properties suggesting that it carried a third-chromosome second-site dominant suppressor of Pros261. Flies heterozygous for this mutagenized chromosome carrying Pros261 were reproducibly viable when reared at the normally restrictive temperature of 29°. In addition, when the chromosome carrying this mutant [referred to here as Su(DTS)] and Pros261 was placed over either Pros261 or Df(3L)st-j7 it was weakly viable at 18°, and it still displayed a synthetic lethal interaction with Prosβ21 at 25°. These phenotypes would not be expected for a pseudorevertant loss-of-function Pros26 allele, suggesting that the original Pros261 allele was still present on this chromosome. Most importantly, the Su(DTS) mutation could be separated by recombination from the Pros261 locus, which maps to 3-45 (or salivary gland chromosome region 73B1). Initial mapping experiments showed that the Su(DTS) mutant resides between the scarlet and stripe genes at approximately 3-50. A second meiotic recombination mapping experiment localized Su(DTS) close to, but to the right of, pink. The interval between pink and stripe corresponds to cytogenetic region 85A6–90E4. During the course of these experiments, lines were established that carried Su(DTS) but no longer carried the Pros261 mutant. In all cases, the recombinant lines were homozygous lethal, suggesting that Su(DTS), in addition to acting as a dominant suppressor of Pros261, has a recessive lethal phenotype as well (also, see below).

Genetic interactions of the Su(DTS) mutant:

The Su(DTS) mutant is a very effective suppressor of the DTS lethal effect of Pros261. In the absence of Su(DTS), individuals carrying Pros261 die during the late larval or pupal stages when reared at 29° (Table 1, line A), while such flies are completely rescued if one copy of Su(DTS) is present (Table 1, line B). The recessive lethal phenotype of Pros261 is only partially suppressed by Su(DTS) and the survivors are slow developing and sick (Table 1, lines C and D). Surprisingly, the Su(DTS) mutant also completely rescues the DTS lethal phenotype associated with the other DTS proteasome mutant, Prosβ21 (Table 1, lines E and F). In addition, there is some rescue from the early larval lethality exhibited by + Pros261/Prosβ21 + trans-heterozygotes, although survivors have small, thin bristles and are infertile (Table 1, lines G and H). The finding that Su(DTS) is able to suppress the DTS phenotype of two different proteasome mutants strongly suggests that its function is closely related to the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway.

TABLE 1.

Genetic interactions among Pros261, Prosβ21, and Su(DTS)

| Cross | Temperature | Tubby ebony | Tubby | Non-Tubby |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. w; Pros261 pb pp/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; +/+ | 29° | — | 452 | 0 |

| B. w; Pros261 Su(DTS)/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; +/+ | 29° | — | 316 | 298 |

| C. w; Pros261 pb pp/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; Pros261 pb pp/TM6B, Tb e ca | 25° | — | 340 | 0 |

| D. w; Pros261 Su(DTS)/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; Pros261 pb pp/TM6B, Tb e ca | 25° | — | 245 | 18 |

| E. w; Prosβ21 st tra in pp//TM6B, Tb e ca × w; +/+ | 29° | — | 429 | 0 |

| F. w; Prosβ21 st tra in pp//TM6B, Tb e ca × w; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM6B, Tb e ca | 29° | 253 | 0 | 305 |

| G. w; Pros261 pb pp/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; Prosβ21 st tra in pp//TM6B, Tb e ca | 25° | — | 283 | 0 |

| H. w; Pros261 Su(DTS)/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; Prosβ21 st tra in pp//TM6B, Tb e ca | 25° | — | 168 | 14 |

| I. w; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM6B, Tb e ca | 25° | 463 | — | 0 |

| J. w; Pros261 Su(DTS)/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM6B, Tb e ca | 25° | 137 | 159 | 28 |

| K. w; Prosβ21 Su(DTS)/TM6B, Tb e ca × w; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM6B, Tb e ca | 25° | 187 | 201 | 0 |

Additional crosses were carried out to investigate the genetic interactions among these three mutants. It was found that not only does the Su(DTS) mutant suppress the DTS lethality of Pros261, but the Pros261 mutant also acts to suppress the recessive lethality of Su(DTS) (Table 1, lines I and J). While this suppression effect is weak, it is significant in that in the absence of Pros261, no homozygous Su(DTS) flies have ever been seen to survive to adulthood. Unlike Pros261, the Prosβ21 mutant did not appear to suppress the recessive lethality of Su(DTS) (Table 1, line K).

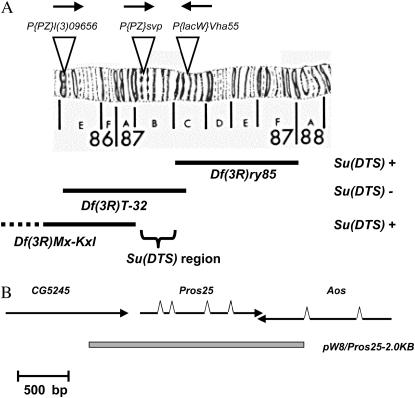

Molecular identification of the Su(DTS) mutant:

As the first step toward its molecular identification, the Su(DTS) mutant was precisely mapped using P-element-mediated site-specific male recombination (Chen et al. 1998). This analysis (described in materials and methods) revealed that both phenotypes of Su(DTS), i.e., the recessive lethality and the dominant suppression of the two DTS proteasome mutants, were caused by mutation(s) in the interval between P{PZ}svp at 87B4–5 and P{lacW}Vha55 at 87C2–3, consistent with the earlier mapping results. Chromosome deficiencies were also used to map the recessive lethal phenotype of Su(DTS) to the same region (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.—

Cytogenetic mapping and molecular identification of the Su(DTS) mutant. (A) The positions of three of the P-element insertions used to map Su(DTS) by site-specific male recombination are shown. The arrows show which side of the element the Su(DTS) mutant was found to map. The solid bars represent the deleted regions of three deficiencies that were used to map the recessive lethal associated with Su(DTS). (B) The molecular structures and orientations of Pros25 and its flanking genes are shown. The shaded bar represents the subcloned fragment that was used for the transgenic rescue experiments.

On the basis of the molecular positions of the defining P-element transposon insertions, the Su(DTS) mutant was delimited to an ∼350-kb region containing 63 annotated genes (Drysdale et al. 2005). Among the genes in this interval are several that have a recognizable relationship to protein stability and degradation, including four Hsp70 protein chaperone genes (Hsp70Ba, Hsp70Bb, Hsp70Bc, and Hsp70Bd), two peptidase genes (CG10041 and Dip-C), and a putative ubiquitin-like protein-activating enzyme (Aos1). The most interesting candidate gene in this region was Pros25, which encodes the α2 subunit of the 20S proteasome (Seelig et al. 1993). Because Pros25 is a component of the same macromolecular complex that contains both Pros26 (β6 subunit) and Prosβ2 (β2 subunit) it seemed likely that Su(DTS) was a mutant allele of this gene. To test this, the Pros25 locus was PCR amplified from homozygous Su(DTS) larvae and analyzed by DNA sequencing. This revealed that there was a G-to-A transition mutation resulting in the replacement of a cysteine with a tyrosine at amino acid position 212. This cysteine is highly conserved, being found in every metazoan α2 subunit that has been sequenced, including those from C. elegans, A. gambii, X. laevis, G. gallus, and H. sapiens. To confirm that this amino acid substitution is not a naturally occurring polymorphism, the Pros25 gene was amplified and sequenced from the Pros261-bearing chromosome carried in the stock used for the suppressor mutant screen. The results showed that the mutation was not present in the original stock and most likely was generated by the ENU treatment. These results strongly suggest that the Su(DTS) mutant is an allele of Pros25. To confirm this, a 2.0-kb KpnI/BamHI restriction fragment containing the wild-type Pros25 gene was isolated from a recombinant BAC clone and subcloned into the pW8 transformation vector, and transgenic lines were established (Figure 2B). The pW8/Pros25-2.0KB transgene was able to completely rescue transgenic flies from the recessive lethality associated with Su(DTS) (Table 2), strongly supporting the idea that the recessive lethal phenotype is the result of mutation in Pros25.

TABLE 2.

Rescue of the Su(DTS) recessive lethal phenotype by a Pros25+ transgene

| F1: genotype | No. |

|---|---|

| Cross (at 25°): w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM3, Sb pp e × w; +/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM3, Sb pp e | |

| A. w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM3, Sb pp e | 45 |

| B. w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca | 22 |

| C. w; +/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM3, Sb pp e | 36 |

| D. w; +/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca | 0 |

To address whether the Pros25 mutation is also responsible for the dominant suppressor of DTS phenotype, Pros25+ transgenic flies carrying an endogenous copy of Su(DTS) were crossed to Prosβ21 and the offspring were raised at 29°. If the suppressor of DTS phenotype is due to the mutation in Pros25, then an extra copy of Pros25+ should counteract this effect. Indeed, in the presence of a transgenic copy of Pros25+, a single dose of Su(DTS) was unable to suppress the DTS phenotype of Prosβ21 (Table 3, lines B and F). These experiments demonstrate that both phenotypes of Su(DTS) are due to the mutation in Pros25, and the mutant is therefore named Pros25SuDTS. This represents the first mutant allele of this gene that has been described.

TABLE 3.

Reversal of the Su(DTS) suppression of DTS lethality of Prosβ21 by a Pros25+ transgene

| F1: genotype | No. |

|---|---|

| Cross (at 29°C): w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM3, Sb pp e × w; +/+; Prosβ21 st tra in pp/TM6B, Tb e ca | |

| A. w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM6B, Tb e ca | 80 |

| B. w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/Prosβ21 st tra in pp | 0 |

| C. w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; Prosβ21 st tra in pp/TM3, Sb pp e | 0 |

| D. w; P{Pros25-2.0 KB, w+}10A/+; TM3, Sb pp e/TM6B, Tb e ca | 6 |

| E. w; +/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/TM6B, Tb e ca | 98 |

| F. w; +/+; st ri pp Su(DTS) e ca/Prosβ21 st tra in pp | 108 |

| G. w; +/+; Prosβ21 st tra in pp/TM3, Sb pp e | 0 |

| H. w; +/+; TM3, Sb pp e/TM6B, Tb e ca | 3 |

Additional phenotypic effects of the Pros25SuDTS mutation:

To examine the recessive lethal phenotype of Pros25SuDTS in more detail, eggs were collected from crosses of w; st ri pp Pros25SuDTS e ca /TM6B, Tb parents and hatching frequency and development of non-Tubby larvae and pupae were monitored at 25°. This analysis showed that there was little if any embryonic lethality associated with Pros25SuDTS homozygotes, but the lethal period was polyphasic throughout the larval and pupal stages. Some of the homozygous larvae exhibited slow growth rate and sluggish behavior, while others progressed through the larval stages with normal appearance and behavior, although pupation was usually delayed a day or two. As pupae, most mutant individuals failed to develop to the late stages, although a few became pharate adults. None of the homozygotes eclosed. In some cases, the dying homozygous larvae exhibited necrotic gut tissue, similar to what has been described for larvae subjected to lethal heat shocks (Krebs and Feder 1997).

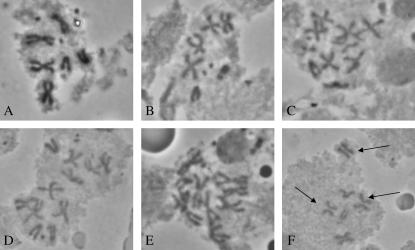

A loss-of-function mutation in another essential proteasome gene, Pros54 encoding the Rpn10 subunit of the 19S regulatory cap, has been shown to cause strong mitosis-defective phenotypes, as seen in dividing larval neuroblasts (Szlanka et al. 2003). To investigate whether the Pros25SuDTS, Pros261, and Prosβ21 proteasome mutants also exhibit mitotic defects, brain squashes from dying mutant larvae were prepared and examined for abnormalities (Figure 3). Pros261 and Prosβ21 heterozygotes, reared at the restrictive temperature of 29°, were selected as late third instar larvae, and brain squashes were prepared either with colchicine treatment, to examine metaphase figures for evidence of aneuploidy and polyploidy, or without such treatment, to determine the mitotic index and to examine anaphase figures. For Pros25SuDTS, brain squashes were prepared from late third instar homozygous larvae raised at 25° or 29°. Unlike what was reported for the Pros54Δp54 mutant (Szlanka et al. 2003), there were few mitotic defects associated with these three proteasome mutants. That is, Pros261/+ and Pros25SuDTS/Pros25SuDTS larval brains showed no apparent instances of polyploidy or aneuploidy, and chromosome morphology and anaphase figures appeared normal (Figure 3, A and B). For Prosβ21/+ larvae, there was a higher than background incidence of tetraploid and aneuploid metaphase figures (Figure 3, C–E), although most (>95%) mitotic spreads were normal. A few mitotic figures showed precocious chromatid separation (Figure 3F). The mean MI and standard errors obtained for the three mutant genotypes were Pros25SuDTS/Pros25SuDTS = 0.97 ± 0.17, Pros261/+ = 1.00 ± 0.14, and Prosβ21/+ = 1.07 ± 0.20. These are somewhat reduced compared to those of wild-type controls (mean MI =1.43 ± 0.18), and this probably reflects the slower developmental rate of the mutant larvae.

Figure 3.—

Metaphase spreads from larval brains of (A) w; Pros25SuDTS/Pros25SuDTS, showing a normal female karyotype; (B) w/Y; Pros261/+, showing a normal male karyotype; and (C–F) w; Prosβ21/+, showing aneuploidy (C–E) and precocious chromatid separation (F) (arrows).

A comparison was made between the lethal phenotypes of Pros25SuDTS/Pros25SuDTS and Pros25SuDTS/Df(3R)T-32 and it was seen that both genotypes showed similar delayed larval development and sluggish behavior, but that Pros25SuDTS/Df(3R)T-32 larvae were more severely affected and did not ever reach the late larval or pupal stages. This suggests that Pros25SuDTS is not a complete loss-of-function allele. When Df(3R)T-32/MKRS flies were crossed to Pros261/TM6B, Tb e ca or Prosβ21/TM6B, Tb e ca and progeny reared at 29°, there were some non-Tubby survivors, although the deficiency was not as effective at suppressing the DTS lethality of these mutants as the Pros25SuDTS mutant. This suggests that reducing the amount or activity of the Pros25 subunit can somehow alleviate the defects caused by the DTS proteasome mutants.

Effect of Pros25SuDTS on proteasome function:

To investigate the mechanism of how Pros25SuDTS suppresses the DTS lethality of Pros261 and Prosβ21, the effect of these three mutants on proteasome function was assessed, using an assay adapted from previous experiments of Schweisguth (1999), who used immunofluoroscopy to monitor the degradation of a known target of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway, the Drosophila Nintra protein. Here, we created a heat-shock-inducible, unstable EGFP by joining a portion of Notch containing its PEST degradation signal (Wesley and Saez 2000) to the carboxy-terminal region of EGFP and placing the fusion gene downstream of the heat-shock promoter in the transformation vector, pCasPer-hs (Thummel and Pirrotta 1992). When transgenic larvae are subjected to a 30-min heat shock at 37°, the EGFP-Nintra reporter protein is ubiquitously expressed, reaching peak fluorescence within 1 hr and then steadily diminishing until it is only weakly detectable after 4 hr (Figure 4, A–C). In contrast, a hs-EGFP transgene, lacking the Notch sequences, produces heat-shock-inducible green fluorescence that is notably more stable and is easily detected 4 hr post-heat shock (Figure 4, D–F). To examine the effects of dominant proteasome mutants on the degradation of heat-shock-induced EGFP-Nintra, the mutant subunits were ectopically expressed in a spatially restricted manner in larval wing discs using the UAS/GAL4 system. In these experiments, a ptc-GAL4 “driver” was used [i.e., P{w+mW.hs= GawB}ptc559.1], which expresses GAL4 in cells along the anterior/posterior boundary of the wing disc (Johnson et al. 1995). If expression of a proteasome mutant subunit inhibits proteasome function (i.e., if it acts in a dominant-negative manner) then the EGFP-Nintra reporter protein should be stabilized, and fluorescence will appear brighter in those cells expressing GAL4. Consistent with the results of Schweisguth (1999) who looked at the effect of Pros261 on Notch-intracellular protein stability, EGFP-Nintra was notably stabilized by the expression of Pros261 (Figure 4G, arrow). A similar inhibition of EGFP-Nintra degradation was seen with expression of Prosβ21 (Figure 4H, arrow). These results confirm that both of these DTS mutants act in a dominant-negative manner to inhibit proteasome activity. Similar ectopic expression of wild-type proteasome subunits, e.g., Pros25 or Pros29 (Pros29 encodes the α3 subunit of the 20S proteasome) (Figure 4, I and J) or of an unrelated control protein, Escherichia coli β-Gal (not shown), had no effect on the stability of EGFP-Nintra, demonstrating that the effect of the DTS mutants is not due to protein overexpression, per se, but is specific to these mutant subunits.

Figure 4.—

Effects of mutant proteasome subunits on the degradation of a heat-shock-inducible green fluorescent protein reporter in larval wing discs. (A–C) Wing discs from w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra, w+}15A(X) larvae. (A) No heat shock, (B) 1 hr post-heat shock, (C) 4 hr post-heat shock. (D–F) Wing discs from w; P{hs-EGFP, w+}25A(3). (D) No heat shock, (E) 1 hr post-heat shock, (F) 4 hr post-heat shock. (G–L) Wing discs, 4 hr post-heat shock from (G) w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra, w+}15A(X)/P{UAS-Pros261, w+}11A(X); P{w+mW.hs=GawB}ptc559.1}/+, (H) w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra, w+}15A(X); P{w+mW.hs=GawB}ptc559.1}/+; P{UAS-Prosβ21, w+}2B(3)/+, (I) w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra, w+}15A(X); P{w+mW.hs=GawB}ptc559.1}/P{UAS-Pros25+, w+}4A(2), (J) w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra, w+}15A(X); P{w+mW.hs=GawB}ptc559.1}/P{UAS-Pros29+, w+}1(2), (K) w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra, w+}15A(X); P{w+mW.hs=GawB}ptc559.1}/P{UAS-Pros25SuDTS, w+}2A(2), and (L) w P{hs-EGFP-Nintra, w+}15A(X); P{w+mW.hs=GawB}ptc559.1}/P{UAS-Pros25SuDTS, w+}2A(2); P{UAS-Prosβ21, w+}2B(3)/+. The arrows point to the stabilization of EGFP-Nintra in the cells expressing the Pros261 or Prosβ21 mutants.

When the Pros25SuDTS mutant alone is expressed in this system, there is no detectable effect on the degradation of EGFP-Nintra (Figure 4K). The simultaneous expression of Pros25SuDTS and Prosβ21, however, restores normal degradation of EGFP-Nintra (Figure 4L), indicating that the mutant Pros25 subunit acts to reverse the dominant-negative effect of Prosβ21 on proteasome function. While this result is not surprising, it is significant in that it demonstrates a direct effect of the suppressor mutant on the function of a gene that it suppresses. This result also demonstrates that the Pros25SuDTS allele is not acting as an amorph or a hypomorph, since its forced expression has a dominant effect on proteasome function in this assay. A simple loss-of-function allele would not be expected to act in such a dominant manner in this system.

DISCUSSION

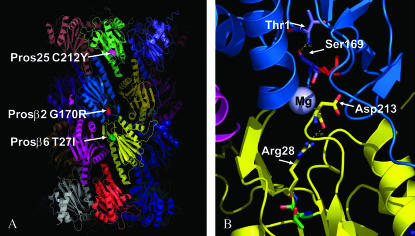

X-ray crystallographic studies of yeast and mammalian proteasomes have shown that the eukaryotic 20S core is highly conserved in its overall structure (Gröll et al. 1997; Unno et al. 2002). Three of the β-type subunits (β1, β2, and β5) are catalytic with the mechanism involving their amino-terminal threonines that face inward toward a large central cavity. Several of the β-type subunits, including all catalytic subunits, are synthesized as proproteins that undergo autocatalytic processing following their assembly into the 20S complex (Schmidtke et al. 1996). The noncatalytic β-type subunits do not have N-terminal threonines; however, they can have effects on proteasome activity through their structural role in forming the degradative chamber where they can physically interact with the substrates' side chains (Gröll et al. 2000). The α-type subunits in the two outer rings have no direct catalytic function, although they do assist in the ordered assembly of the 20S particle (Schmidtke et al. 1996), and they may play regulatory roles. For example, the α-rings form antechambers through which unfolded polypeptides must pass, and it is possible that there are regulatory interactions between the α-subunits and the substrate as it awaits entry into the innermost chamber. The α-subunits also interact directly with the 19S cap and with an alternative regulator called the 11S complex, and they can affect the subcellular distribution of proteasomes via nuclear localization signals present on α1, α2, α3, and α4 (Unno et al. 2002). The 20S proteasome is not ordinarily an open cylinder, but is sealed off at each end by the N-terminal tails of α2, α3, and α4 and an internal loop of α5 (Gröll et al. 2000; Unno et al. 2002). This gate must be opened before a substrate can enter the core, a task performed by regulatory complexes such as the 19S cap. Although these general features of the structure and function of the proteasome are known, the exact roles of each of the individual subunits are less well understood. For example, it is not known if the α2 subunit encoded by Pros25 has any special function that is distinct from the roles of α-type subunits in general.

The genetic and biochemical properties of the Prosβ21 and Pros261 mutants suggest that they encode abnormal β2 and β6 subunits that incorporate into proteasome particles and interfere with their function (Saville and Belote 1993; Covi et al. 1999; Schweisguth 1999; Smyth and Belote 1999). This “poison subunit” hypothesis explains how these mutants act in a dominant-negative fashion (Herskowitz 1987). However, the exact mechanism by which these abnormal subunits are interfering with proteasome activity is not known. Although the Drosophila proteasome structure has not been solved, the high degree of structural similarity between the yeast and bovine structures suggests that the fly 20S particle does not differ in its overall structure from those two. Using the bovine proteasome as the model, in Prosβ21 there is a replacement in the β2 subunit of a highly conserved glycine by an arginine at amino acid position 170 (or 209 before autocatalytic processing). This is in a loop between α-helix four and β-sheet nine and is located near the active site of β2 in the three-dimensional (3D) structure (Figure 5). This loop may be critical for stabilizing the interaction between the β2 and β6 subunits in adjacent rings. For example, the carbonyl oxygen of Ser169 in β2 interacts via a magnesium ion bridge with the C-terminal aspartate (Asp213) of the β6 subunit. It is likely that the substitution of a bulky arginine for Gly170 would reduce the flexibility of the loop and interfere with Mg2+ binding. This might not only affect the stability of the β2–β6 interaction but it could also very well have a direct effect on catalytic function, since the γ-hydroxyl side chain of the highly conserved Ser169 of β2 is only 3.0 Å from the amino group of its active site threonine (Figure 5B). This is close enough to provide a stabilizing influence on its positioning via hydrogen bonding. A shift in the position of Ser169 caused by the Gly170Arg substitution in Prosβ21 could thereby interfere with the active site of the β2 subunit. This shift might be expected to occur more readily at elevated temperature, thus explaining the temperature sensitivity of this mutant.

Figure 5.—

X-ray structure of the bovine 20S proteasome as determined by Unno et al. (2002). (A) Ribbon diagram of the 20S proteasome showing the relative positions of the amino acid substitutions in the Drosophila Pros25SuDTS (α2 subunit), Prosβ21 (β2 subunit), and Pros261 (β6 subunit) mutants. The α2 subunit is light green, β2 is blue, and β6 is yellow. The corresponding sites of the Pros25SuDTS, Prosβ21, and Pros261 amino acid substitutions are shown in magenta, red, and green, respectively. (B) Spatial relationship between the Gly170 of β2 (red) and the Thr27 of β6 (green). Also shown is the Mg2+ ion that forms a bridge between Ser169 of β2 and Asp213 of β6. The N-terminal active site threonine (Thr1) of β2 is 3.01 Å away from Ser169. Arg28 of β6 is 2.95 Å from Asp213. All of these residues are conserved between the bovine and fly proteasomes.

In Pros261, there is a threonine to isoleucine substitution at position 27 (or position 47 before processing) of the β6 subunit. This change occurs in a highly conserved loop between β-sheets two and three, immediately adjacent to an arginine (Arg28) that forms a salt bridge with the C-terminal carbonyl of the Asp213, mentioned above as important for Mg2+ binding (Figure 5B). This Thr27Ile substitution may cause a subtle structural shift that alters the position of Arg28, which could then indirectly affect the Mg2+ binding pocket and interfere with the β2–β6 interaction, or it might inhibit the catalytic function of β2 as described above. The importance of this spatial relationship among a C-terminal aspartate, a magnesium ion, Ser169, and the active site threonine (Thr1) is highlighted by the fact that a similar type of arrangement is seen in the structure surrounding the active site of the β5 subunit. In that case a magnesium ion bridges an interaction between the C-terminal aspartate of β3 and Ser169 of β5, with the side-chain hydroxyl of Ser169 interacting with the amino group of the active site threonine of β5. The significance of Mg2+ is supported by results of in vitro assays in which proteasome activity is stimulated by the presence of magnesium ions (Pereira et al. 1992).

In Pros25SuDTS the Cys212Tyr replacement occurs at the end of β-sheet eight in a position that is partially surface exposed (Figure 5A). The results described here show that the mutant subunit can act in a dominant manner to rescue the temperature-sensitive lethality of both Prosβ21 and Pros261, and in the case of Prosβ21 this has been shown to be associated with a restoration of proteasome functional activity. This suppression is not likely due to a direct compensating effect of the Cys212Tyr replacement in Pros25SuDTS interacting with the Gly170Arg substitution in Prosβ21 or the Thr27Ile mutation in Pros261, given their relatively remote positions in the predicted 3D structure (Figure 5A). It seems more likely that the mutant α2 subunit in Pros25SuDTS is indirectly counterbalancing the inhibitory effects of the Prosβ21 and Pros261 mutations in β2 and β6, respectively. For example, it may be that the Cys212Tyr replacement in the α2 subunit results in a more effective movement of polypeptides through the proteasome and that this gain in proteasome efficiency helps overcome the slowdown in proteolysis caused by the β-subunit mutations. If this is true, it is not obvious what the mechanistic basis for this is. The position of Cys212Tyr appears too far from the N-terminal tail in the 3D structure to affect the gating of the 20S proteasome, and it is not exposed to the internal antechamber, so it would not be expected to interact directly with proteasome substrates. It is possible that the substitution of the cysteine with a bulky aromatic tyrosine might have an effect on the overall folding of the α2 subunit, and this change in tertiary structure could have unpredictable effects. Since the α2 subunit has been shown to interact directly with the 11S proteasome regulator (Kania et al. 1996) it is also conceivable that the mutant α2 subunit might affect proteasome activity through an interaction with this or the 19S cap.

Whatever the mechanism, the suppression of a proteasome mutant by mutation in a gene encoding another proteasome subunit has a precedent. In S. cerevisiae, the crl3-2 mutant is a temperature-sensitive lethal allele of the gene encoding the Rpt6 subunit of the 19S regulatory cap (Gerlinger et al. 1997). A dominant suppressor of crl3-2, called SCL1-1, was isolated and subsequently found to represent a mutant of the gene encoding the α1 subunit of the 20S core (Balzi et al. 1989; Gerlinger et al. 1997). Biochemical analyses of proteasome function showed that while the crl3-2 mutant had defective proteasome activity, in crl3-2 SCL1-1 double mutants proteasome function is restored (Gerlinger et al. 1997). As is the case with our study, the mechanistic basis of this suppression is unknown.

Regardless of how Pros25Su(DTS) suppresses both Pros261 and Prosβ21, the results described here demonstrate that this type of suppressor screen might be used to efficiently isolate new proteasome mutants. Because the suppression phenotype, i.e., viability, is very easy to identify in this screen, it should be feasible to carry out such a screen on a large scale to identify additional proteasome mutants. By using different combinations of the dominant-negative conditional mutants and dominant suppressors, in conjunction with the UAS/GAL4 system, it may be possible to finely tune proteasome malfunction in a targeted manner. Such a system might be useful in cases where drastic effects on proteasome function might be too harmful to assess the role of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway on the process of interest.

To date, only a few proteasome mutants have been identified in Drosophila, and most are severe loss-of-function alleles that act as recessive, embryonic, or early larval lethals. For example, recessive lethal alleles of the Prosβ2, Prosβ5, and Prosβ6 20S proteasome subunit genes have been isolated and they behave as amorphs, or severe hypomorphs, with lethality occurring soon after hatching from the embryo (Saville and Belote 1993; Smyth and Belote 1999; S. Eaton, personal communication). It is likely that maternal contribution of proteasome subunits or their mRNAs prevents these mutants from exhibiting an earlier lethal phase (Ma et al. 2002). A null allele of the gene encoding the 19S regulatory particle subunit Rpn10 has a pupal lethal period (Szlanka et al. 2003). Recent efforts of large-scale gene disruption projects have resulted in the identification of transposon insertion alleles of a few other proteasome subunits, but they have yet to be studied in detail.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following former members of the Belote lab for contributions to this study: Jacqueline Todd, Stephanie Brewer, and Karla Vitale. We are also indebted to Mary Miller, Jing Ma, Deitmar Zaiss, Eric Fortier, Evan Katz, Lei Zhong, Xiazhen Li, Damian Fermin, Nathan Billings, Segan Millington, and Richard Krolewski for useful discussions and encouragement. We thank Michael Cosgrove for his insight and assistance in preparing Figure 5 and Carl Thummel for providing the pCaSpeR-hs plasmid. This work was supported by grants to J.M.B. from the National Science Foundation and by a Syracuse University Ruth Meyer Undergraduate Research Award and a Korczynski–Lundgren Memorial Award to P.J.N.

References

- Adams, A. E. M., and D. Botstein, 1989. Dominant suppressors of yeast actin mutations that are reciprocally suppressed. Genetics 121: 675–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzi, E., W. N. Chen, E. Capieaux, J. H. McCusker, J. E. Haber et al., 1989. The suppressor gene scl1+ of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is essential for growth Gene 83: 271–279 (erratum: Gene 89: 151). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belote, J. M., and E. Fortier, 2002. Targeted expression of dominant negative proteasome mutants in Drosophila. Genesis 34: 80–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A. H., and N. Perrimon, 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H. Y., J. M. Warrick, I. Andriola, D. Merry and N. M. Bonini, 2002. Genetic modulation of polyglutamine toxicity by protein conjugation pathways in Drosophila. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11: 2895–2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B., T. Chu, E. Harms, J. P. Gergen and S. Strickland, 1998. Mapping of Drosophila mutations using site-specific male recombination. Genetics 149: 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covi, J. A., J. M. Belote and D. L. Mykles, 1999. Subunit compositions and catalytic properties of proteasomes from developmental temperature-sensitive mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 368: 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio, A., and L. Hicke, 2004. Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of the synapse. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27: 223–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, M., A. Crosby and The FlyBase Consortium, 2005. FlyBase: genes and gene models. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: D390–D395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J., and D. Xue, 2004. To live or die by the sword: the regulation of apoptosis by the proteasome. Dev. Cell 6: 460–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, M., and B. S. Baker, 1989. Genes controlling essential cell-cycle functions in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 3: 438–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger, U.-M., R. Gückel, M. Hoffmann, D. H. Wolf and W. Hilt, 1997. Yeast cycloheximide-resistant crl mutants are proteasome mutants defective in protein degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 8: 2487–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman, M. H., and A. Ciechanover, 2002. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol. Rev. 82: 373–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor, G., and W. Engels, 1992. Single fly DNA preps for PCR. Dros. Inf. Serv. 71: 148. [Google Scholar]

- Gröll, M., L. Ditzel, J. Löwe, D. Stock, M. Bochtler et al., 1997. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4Å resolution. Nature 386: 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröll, M., M. Bajorek, A. Kohler, L. Moroder, D. M. Rubin et al., 2000. A gated channel into the proteasome core particle. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7: 1062–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, R. Y., and H. Bhakta, 1997. Ubiquitin-mediated regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 12944–12948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, A. N., and S. C. Upadhya, 2006. Proteasome and transcription: a destroyer goes into construction. BioEssays 28: 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henchoz, S., F. De Rubertis, D. Pauli and P. Spierer, 1996. The dose of a putative ubiquitin-specific protease affects position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 5717–5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heriche, J. K., D. Ang, E. Bier and P. H. O'Farrell, 2003. Involvement of an SCFSlmb complex in timely elimination of E2F upon initiation of DNA replication in Drosophila. BMC Genet. 4: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz, I., 1987. Functional inactivation of genes by dominant negative mutations. Nature 329: 219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden, J. J., and D. T. Suzuki, 1973. Temperature-sensitive mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. XII. The genetic and developmental effects of dominant lethals on chromosome 3. Genetics 73: 445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, R. A., C. R. Nelson, B. P. Berman, T. R. Laverty, R. A. George et al., 2000. A BAC-based physical map of the major autosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287: 2271–2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y., R. T. Baker and J. A. Fischer-Vize, 1995. Control of cell fate by a deubiquitinating enzyme encoded by the fat facets gene. Science 270: 1828–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffaker, T. C., M. A. Hoyt and D. Botstein, 1987. Genetic analysis of the yeast cytoskeleton. Annu. Rev. Genet. 21: 259–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. L., J. K. Grenier and M. P. Scott, 1995. Patched overexpression alters wing disc size and pattern: transcriptional and post-translational effects on hedgehog targets. Development 121: 4161–4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kania, M. A., G. N. Demartino, W. Baumeister and A. L. Goldberg, 1996. The proteasome subunit, C2, contains an important site for binding of the PA28 (11S) activator. Eur. J. Biochem. 236: 510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyamu, H. K., J. Chen and T. K. Archer, 2005. Linking the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to chromatin remodeling/modification by nuclear receptors. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 34: 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloetzel, P. M., 2004. The proteasome and MHC class I antigen processing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1695: 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostova, Z., and D. H. Wolf, 2003. For whom the bell tolls: protein quality control of the endoplasmic reticulum and the ubiquitin–proteasome connection. EMBO J. 10: 2309–2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, R. A., and M. E. Feder, 1997. Tissue-specific variation in Hsp70 expression and thermal damage in Drosophila melanogaster larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 200: 2007–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush, R. S., W. D. Cornwell, J. N. Uram and B. Lemaitre, 2002. A ubiquitin-proteasome pathway represses the Drosophila immune deficiency signaling cascade. Curr. Biol. 12: 1728–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J., 2001. The α3T gene of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a spermatogenesis-specific proteasome subunit. Ph.D. Dissertation, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY.

- Ma, J., E. Katz and J. M. Belote, 2002. Expression of proteasome subunit isoforms during spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol. Biol. 11: 627–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung, J., K. B. Kim and C. M. Crews, 2001. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and proteasome inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 21: 245–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, N., W. Song, M. Hunter-Ensor and A. Sehgal, 1999. A role for the proteasome in the light response of the timeless clock protein. Science 285: 1737–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick, P., B. C. Osmond and D. Botstein, 1989. Suppressors of yeast actin mutations. Genetics 121: 659–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, S. I., 2003. Ratchets and clocks: the cell cycle, ubiquinilation and protein turnover. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4: 855–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M. E., B. Yu and S. Wilk, 1992. Enzymatic changes of the bovine pituitary multicatalytic proteinase complex, induced by magnesium ions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 294: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch and T. Maniatis, 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Saville, K. J., and J. M. Belote, 1993. Identification of an essential gene, l(3)73Ai, with a dominant temperature-sensitive lethal allele, encoding a Drosophila proteasome subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90: 8842–8846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke, G., R. Kraft, S. Kostka, P. Henklein, C. Frömmel et al., 1996. Analysis of mammalian 20S proteasome biogenesis: the maturation of β-subunits is an ordered two-step mechanism involving autocatalysis. EMBO J. 15: 6887–6889. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweisguth, F., 1999. Dominant-negative mutations in the β2 and β6 proteasome subunit genes affect alternative cell fate decisions in the Drosophila sense organ lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 11382–11386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelig, A., M. Troxell and P. M. Kloetzel, 1993. Sequence and genomic organization of the Drosophila proteasome PROS-Dm25 gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1174: 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, J. M., and M. B. Feany, 2003. Genetic modifiers of tautopathy in Drosophila. Genetics 165: 1233–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, K. A., and J. M. Belote, 1999. The dominant temperature-sensitive lethal mutant DTS7 of Drosophila melanogaster encodes an altered 20S proteasome β-type subunit. Genetics 151: 211–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speese, S. D., N. Trotta, C. K. Rodesch, B. Aravamudan and K. Broadie, 2003. The ubiquitin proteasome system acutely regulates presynaptic protein turnover and synaptic efficacy. Curr. Biol. 13: 899–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szlanka, T., L. Haracska, I. Kiss, P. Deak, E. Kurucz et al., 2003. Deletion of proteasomal subunit S5a/Rpn10/p54 causes lethality, multiple mitotic defects and overexpression of proteasomal genes in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Sci. 116: 1023–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H., S. B. Rompani, J. B. Atkins, Y. Zhou, T. Osterwalder et al., 2005. Numb proteins specify asymmetric cell fates via an endocytosis- and proteasome-independent pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 2899–2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel, C. S., and V. Pirrotta, 1992 New pCaSpeR P element vectors. Dros. Inf. Serv. 71: 150.

- Unno, M., T. Mizushima, Y. Morimoto, Y. Tomisugi, K. Tanaka et al., 2002. The structure of the mammalian 20S proteasome at 2.75 A resolution. Structure 10: 609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley, C. S., and L. Saez, 2000. Analysis of Notch lacking the carboxyl terminus identified in Drosophila embryos. J. Cell Biol. 149: 683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y., and M. E. Fortini, 2000. Proteolysis and developmental signal transduction. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11: 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]