Abstract

Wing development in Drosophila is a common model system for the dissection of genetic networks and their roles during development. In particular, the RTK and TGF-β regulatory networks appear to be involved with numerous aspects of wing development, including patterning, cell determination, growth, proliferation, and survival in the developing imaginal wing disc. However, little is known as to how subtle changes in the function of these genes may contribute to quantitative variation for wing shape, per se. In this study 50 insertional mutations, representing 43 loci in the RTK, Hedgehog, TGF-β pathways, and their genetically interacting factors were used to study the role of these networks on wing shape. To concurrently examine how genetic background modulates the effects of the mutation, each insertion was introgressed into two wild-type genetic backgrounds. Using geometric morphometric methods, it is shown that the majority of these mutations have profound effects on shape but not size of the wing when measured as heterozygotes. To examine the relationships between how each mutation affects wing shape hierarchical clustering was used. Unlike previous observations of environmental canalization, these mutations did not generally increase within-line variation relative to their wild-type counterparts. These results provide an entry point into the genetics of wing shape and are discussed within the framework of the dissection of complex phenotypes.

IN quantitative and evolutionary genetics, the focus has primarily been on using QTL and linkage disequilibrium mapping to hunt for genes, but large-scale screens using mutagenesis have also been employed for traits such as bristle number and olfaction (Mackay et al. 1992; Anholt et al. 1996; Norga et al. 2003). These studies not only enrich the list of possible candidate genes harboring natural genetic variation, but also provide estimates for the mutational target size of these traits. Nonetheless it remains unclear if genes characterized in functional studies are good candidates for studies of natural variation. One facet that needs to be investigated is whether minor variation in gene function is sufficient to affect the expression of quantitative traits. In general, developmental processes such as patterning and determination have been addressed with classical Mendelian and molecular genetic approaches. However, a number of studies have demonstrated the utility of quantitative genetic methodologies for examining natural genetic variation for these developmental mechanisms (Gibson and Hogness 1996; Gibson and van Helden 1997; Polaczyk et al. 1998; Palsson and Gibson 2000; Atallah et al. 2004). We recently utilized association mapping to localize naturally occurring polymorphisms involved with variation for photoreceptor determination in Drosophila (Dworkin et al. 2003). Although evidence is still limited, these studies are consistent with genes of major effect harboring alleles that contribute to quantitative trait variation.

With respect to the genetic dissection of development, the wing of Drosophila melanogaster is one of the best established model systems (Held 2002). During embryonic development, a set of ∼24 cells invaginate from the epithilium to form the wing disc rudiment (Cohen et al. 1991). During early larval development, broad patterning of the wing axes is established. In particular, the posterior region of the wing imaginal disc is patterned by the protein Engrailed (En) (Garcia-Bellido and Santamaria 1972; Lawrence and Morata 1976; Brower 1986). En activates the short-range paracrine signaling ligand hedgehog (∼2–4 cell widths) at the boundary between the anterior and posterior territories (Hidalgo 1994; Tabata and Kornberg 1994; Sanicola et al. 1995). Hedgehog upregulates decapentaplegic, the canonical ligand of the TGF-β signaling pathway (Zecca et al. 1995). While dpp RNA is present only in an ∼5-cell-wide region just anterior to the anterior–posterior (A–P) boundary, the Dpp secreted protein elicits long-range effects throughout the future wing blade (at least 35 cell diameters from its source), regulating a number of downstream target genes that specify domains along the A–P axis (Podos and Ferguson 1999; Held 2002). These future wing territories are further subdivided into vein and intervein fates by the regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. During early pupal development, the TGF-β pathway is reutilized in the maintenance of vein–intervein fates (Held 2002; De Celis 2003; Crozatier et al. 2004). The above description is a gross simplification of the process and of the role of these genes. For instance, members of both the TGF-β and receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathways have been implicated in other developmental processes in the wing such as cell growth and survival (Martin et al. 2004). In addition, there is evidence for “cross-talk” between pathways with respect to vein–intervein determination (Crozatier et al. 2002; Yan et al. 2004; Sotillos and De Celis 2005), and they appear to interact as networks, rather than linear pathways.

While there is a wealth of information with respect to the role of these genes during the development of the wing, little is known about the genetic modification of wing shape. That is, it is unclear how the wing takes on its final adult dimensions. Geometric morphometric methods, a recent development in the analysis of shape (Bookstein 1991; Zelditch et al. 2004), allow for sensitive discrimination between groups or treatments (Klingenberg 2002; Houle et al. 2003). These methods have primarily been used to characterize naturally occurring variation, with little attempt to understand the developmental basis for shape differences. With respect to wing shape in D. melanogaster, a number of studies have demonstrated moderate to high heritability for the phenotype (Weber 1990; Birdsall et al. 2000; Zimmerman et al. 2000; Palsson and Gibson 2004; Mezey et al. 2005), and there is little evidence for constraints on the evolution of shape (Mezey and Houle 2005). Consistent with a large mutational target size for wing shape, ∼20% of novel P-element insertion lines demonstrated replicable phenotypic effects on shape (Weber et al. 2005). In addition, it is clear that there is considerable segregating genetic variation in natural populations for wing shape (Weber 1990; Weber et al. 1999; Birdsall et al. 2000; Zimmerman et al. 2000; Mezey et al. 2005).

Concerning the contribution of individual genes on wing shape, deficiency complementation mapping has been used to investigate the role of candidate gene function on shape (Palsson and Gibson 2000; Mezey et al. 2005). In addition, a series of studies have demonstrated how a putative regulatory polymorphism in the Egfr gene is associated with natural variation for wing shape (Palsson and Gibson 2004; Dworkin et al. 2005; Palsson et al. 2005). Unfortunately, none of this work was performed in controlled genetic backgrounds to investigate the individual effects of mutations in these genes. One exception is the study by Weber et al. (2005), which demonstrated that 11 of 50 random P-element insertion lines had a significant effect in an isogenic background on the basis of at least one of four univariate measures of wing allometry. Plasmid rescue of these insertions suggests that putative genes were involved in a variety of developmental and physiological processes. Notably, the method used to examine shape for this study likely underestimated phenotypic variation in the wing.

In this study we investigate the potential role of genes in the EGF, TGF-β, and Hedgehog signaling pathways with respect to wing shape in Drosophila. Fifty P-element insertional mutations in genes from these pathways were introgressed into each of two standard lab wild-type strains. Wing shape was then measured on heterozygotes for each mutation and compared to their respective wild-type congenics. With this experimental framework, we addressed several questions: (1) Given that genes in the TGF-β and EGF/RTK signaling pathways are involved with various aspects of wing development, what role might they and their interacting factors play in wing shape?, (2) What are the effects of the mutations when measured in a heterozygous state?, (3) How important is genetic background when estimating the effects of the mutations on shape?, (4) Do the effects of the mutations on shape make sense on the basis of their known developmental roles?, and (5) Do mutations within genes from the same pathway tend to have “related” effects on shape when compared with mutations in genes from different pathways?

We demonstrate that the mutations in most of the genes under study show a significant effect on shape relative to their wild-type counterparts when measured in a heterozygous state. However, it is clear that genetic background plays an important role in describing shape both as marginal and as epistatic effects. Furthermore we demonstrate that while some of the mutations clearly affect shape in a similar manner with respect to their known function, the effects of the mutations on shape do not cluster on the basis of pathways, consistent with extensive cross-talk. These results are discussed within the framework of the role of TGF-β and RTK signaling on wing shape and their potential as candidate genes that harbor segregating variation for shape.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stocks:

Insertional mutations were selected from the Bloomington Stock Center (Table 1). Many of the insertions were considered “within” genes if they were within 5 kb of the ORF of that gene or showed a failure to complement with other known mutations in those genes (Table 1). Regardless of the original source of the insertion, each transposon used was marked with a mini-white (P{w+}), as this facilitated the backcross procedure.

TABLE 1.

A list of mutations used in this study

| Gene (abbreviation) | Allele | Phenotype/complementation | Genetic pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| argos (aos) | W11 | L* | Egfr |

| asteroid (ast) | kg07563 | EV | Egfr |

| baboon (babo) | k16912 | L* | TGF-β/Hh |

| blistered (bs/DSRF) | k07909 | L, EV* | Egfr |

| brinker (brk) | kg08470 | ND* | TGF-β |

| cable (cbl) | kg03080 | L | Egfr |

| cAMP-dependent protein kinase 1 (Pka-C1) | BG02142 | L* | Hh |

| cAMP-dependent protein kinase 3 (Pka-C3) | kg00222 | ND | Hh |

| CG3957/wmd | kg07581 | WMD | Unknown |

| corkscrew (csw) | G0170 | L | Egfr |

| costal-2 (cos) | k16101 | L | Hh |

| crossveinless-2 (cv-2) | 225-3 | PCVL | TGF-β |

| Daughters against Dpp (Dad) | J1E4 | EV | TGF-β |

| decapentaplegic (dpp) | kg04600 | L | TGF-β |

| decapentaplegic (dpp) | kg08191 | L* | TGF-β |

| downstream of receptor kinases (drk) | k02401 | L* | Egfr |

| downstream of receptor kinases (drk) | kg03077 | EV | Egfr |

| echinoid (ed) | k01102 | L/C | Egfr |

| Epidermal growth factor Receptor (egfr) | k05115 | L* | Egfr |

| GTPase activating protein1 (GAP1) | mip-w[+] | L* | Egfr |

| kinase suppressor of ras (ksr) | J5E2 | L | Egfr |

| mastermind (mam) | BG02477 | L* | N/Egfr |

| mastermind (mam) | kg02641 | L* | N/Egfr |

| Mothers against Dpp (Mad) | k00237 | L* | TGF-β |

| Mothers against Dpp (Mad) | kg00581 | L* | TGF-β |

| optomotor blind (omb) | md653 | D, LOP | TGF-β |

| osa | kg03117 | L | Chromatin-remodeling |

| p38b | kg01337 | ND | TGF-β/Egfr |

| patched (ptc) | k02507 | L | Hh |

| pipsqueak (psq) | kg00811 | L | Chromatin-remodeling/Egfr |

| pointed (pnt) | kg04968 | L | Egfr |

| Ras GTPase-activating protein (RasGAP) | kg02382 | Egfr | |

| RAS85D | EY00505 | ND | Egfr |

| rho kinase (rho1) | kg01774 | ND/C | Egfr? |

| rhoAP/CG7044 | BG00314 | ND | ? |

| rhomboid/rhomboid-2 (rho/stet)a | kg07115 | DVL* | Egfr |

| rhomboid-6 (rho-6) | kg05638 | ND | Egfr |

| rhomboid-6 (rho-6) | kg09603 | ND/C | Egfr |

| saxophone (sax) | sax4 | L* | TGF-β |

| saxophone (sax) | kg07525 | EV* | TGF-β |

| scalloped (sd) | E3 | sd | TGF-β/Egfr |

| schnurri (shn) | k00401 | L* | TGF-β |

| scribbler (sbb/mtv) | BG01610 | L* | TGF-β |

| spitz (spi) | s3547 | L* | Egfr |

| Src42A | kg02515 | ND | Egfr |

| Star (S) | k09530 | L | Egfr |

| teashirt (tsh) | A3-2-66 | EV, M | TGF-β |

| thickveins (tkv) | k19713 | L/C | TGF-β |

| thickveins (tkv) | kg01923 | EV* | TGF-β |

| Trithorax-like (Trl) | S2325 | L | Chromatin-remodeling/Egfr |

A list of the mutations used in this experiment and the pathways in which they are involved is shown. Homozygous/hemizygous effects of the alleles on wing phenotypes: L, lethal as adult; ND, no wing defects; sd, scalloped wing; D, delta-like phenotypes; EV, ectopic vein material; PCVL, posterior crossveinless; DVL, distal veinless, M, margin defects; WMD, wing morphogenesis defects; LOP, loss of central wing pouch. * failure to complement additional alleles of this gene; C, allele complementation.

While the sequence listed suggests that this is an allele of rho-2, the homozygous phenotype and complementation tests suggest that it is in fact allelic to rhomboid, which is adjacent to rho-2 (personal observation).

All insertions were introgressed into two wild-type lab strains, Samarkand (Sam) and Oregon-R (Ore), both marked with white (w), resulting in white-eyed flies. Introgressions were performed by repeated backcrossing of females bearing the insertion to males of Sam and Ore-R. Replicate backcrosses were performed for each of 14 generations, and females from both replicate vials were pooled for the following generation of backcrossing. Selection was based entirely on the presence of the eye color marker, precluding unwitting selection for wing phenotypes. Due to the low viability of the wild-type Oregon-R line, seven of the mutant alleles could not be maintained in the Oregon-R background. While the introgression procedure should make the genome of the mutant largely identical to that of the isogenic wild types, there is the possibility of segregating alleles from the genetic background of the mutant allele, particularly sites closely linked to the mutation being introgressed. Therefore all experimental comparisons of mutant individuals were made with wild-type siblings from a given cross and thus should share any remaining segregating alleles unlinked to the P element. All crosses were performed using standard media, in a 25° incubator on a 12/12-hr light/dark cycle.

Experimental setup:

In generations 9 and 14 of the backcrossing, two vials for each line were set up as described in the previous section. Care was taken that each vial had five females and three males, and the parents were removed after several days of egg laying, resulting in low to moderate larval density. The temperature of the incubator was monitored carefully for fluctuations, and vial position was randomized within the incubator on a daily basis to reduce any possible edge effects. As larvae crawled out of the media, a piece of paper towel was added to each vial to provide additional pupation space. After eclosion and sclerotization, flies were separated into wild-type individuals without the P-element-induced mutations (w; +/+) from those heterozygous for the P element (w; P{w+}/+) on the basis of eye color and stored in 70% ethanol.

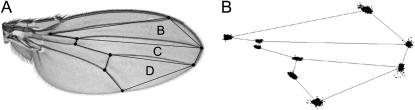

A single wing from each fly was dissected and mounted in glycerol (10 wings per sex/genotype/background/replicate). Images of the wings were captured using a SPOT camera mounted on a Nikon Eclipse microscope. Landmarks (Figure 1) were digitized using the tpsDig (v. 1.39, Rohlf 2003) software. In addition to analyzing the data set with all nine landmarks, the B, C, and D regions (Figure 1) were separately aligned and analyzed. These regions were examined on the basis of developmental arguments that suggest that some genes may function independently in these regions to define shape (Birdsall et al. 2000; Palsson and Gibson 2004).

Figure 1.—

The wing blade of Drosophila melanogaster. (A) Image of a wing from D. melanogaster, with the nine landmarks used in this study superimposed as solid circles. In addition to studying variation across the entire wing, regional variation was also examined for the anterior (B), central (C), and posterior (D) areas of the wing. (B) Variation in landmark position after procrustes superimposition for all samples used in this study.

Analysis:

Procrustes superimposition of landmarks:

In a mathematical framework, shape is defined as the residual variation in landmark displacement once position, isometric scale, and rotation are accounted for (Bookstein 1991; Zelditch et al. 2004). In the framework of geometric morphometrics, a procedure is used where all individual configurations of landmarks are scaled to a common centroid size, the square root of the sum of the squared distances of each landmark from the centroid (center of mass) of the configuration. The remaining variation will be uncorrelated with isometric scaling on size, and allometric effects of size on shape can be accounted for by including size as a covariate in the statistical analysis. The effects of rotation are minimized by utilizing an iterative, generalized least-squares approach commonly described as procrustes superimposition (GPA). For an introduction to these methods please refer to Zelditch et al. (2004).

Correcting for multiple testing:

To explicitly examine the unique effects of each mutation on wing size and shape, individual tests on each mutation in the context of mutant genotype, sex, and genetic background (Sam vs. Ore-R) were employed. Given that this results in multiple testing problems, a Bonferroni correction procedure was used to adjust the nominal critical threshold for statistical significance.

Wing size:

To examine the effects of the independent variables on wing size, centroid size of the nine-landmark configuration (Figure 1B) was used in the following model for each replicate and line,

|

where G is genotype, S is sex, and B is background, all fixed effects. The analysis was performed in PROC GLM (SAS 8.2). To account for the large replicate effects observed (Table 2), probabilities from each replicate measure were combined using Fisher's method  , combined over both replicates and evaluated assuming a

, combined over both replicates and evaluated assuming a  -distribution (Sokal and Rohlf 1995), where k = number of tests (one for each replicate).

-distribution (Sokal and Rohlf 1995), where k = number of tests (one for each replicate).

TABLE 2.

The effect of sex and genetic background on centroid size

| Source | d.f./ d.f. error | MS | F-value | Prob F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1/6.2 | 3,303,446 | 87.4 | 7.14E-05 |

| Background | 1/6.15 | 602,429.3 | 14.7 | 0.008 |

| Sex × background | 1/6.15 | 38,359.54 | 0.936 | 0.37 |

| Rep(sex × background) | 6/3695 | 67,063.1 | 54.1 | 2.89E-64 |

| Residual | 3,695 | 1,239 |

ANOVA summary for the overall model for the wild-type control flies. d.f. error, error degrees of freedom; Rep, replicate.

Wing shape:

To make statistical inferences about the effects of treatments (sex, genotype, and background) on shape, a fully multivariate approach was used. For each mutation, the following model was employed,

|

where y is the vector of partial warp and uniform components, g is the genotype (mutant vs. wild type), b is the wild-type background (Sam vs. Ore-R), s is sex, e is residual error, and c is centroid size, used as a covariate in the model to control for allometric effects. The analysis was performed using the MANOVA function in PROC GLM (SAS 8.2), with similar results observed using a multivariate regression using the tpsRegr v. 1.3 (Rohlf 2004). Given the 50 independent mutations that were used, Bonferroni correction for multiple tests indicates that P = 0.001 is the nominal critical value for α = 0.05. Log transformation of centroid size had negligible effects on the results when included as a covariate (not shown). In addition, a test for homogeneity of slopes was performed, and the null hypothesis of a common slope for each genotypic comparison (mutant vs. wild type) could not be rejected.

Given that it is generally unclear if shape variables conform to the parametric assumptions for a MANOVA, 1000 permutations of the data (for each line) were performed to empirically assess the critical values for the MANOVA across the entire wing blade. The results of the permutations were similar to those observed from the parametric tests that were obtained (not shown). Permutations were performed in SAS using a modified macro (Cassell 2002).

Estimated effect of genotype on shape:

To estimate the mean treatment effects (genotype, sex, and background) on shape, the procrustes distance (PD) was calculated between groups. Procrustes distance between group means was calculated as  , where x represents the difference vector calculated from the treatment means of the procrustes residuals for each landmark. Results with Mahalanobis distance on the partial warps and uniform components were highly concordant (Spearman's r = 0.9) with those of procrustes distance (not shown).

, where x represents the difference vector calculated from the treatment means of the procrustes residuals for each landmark. Results with Mahalanobis distance on the partial warps and uniform components were highly concordant (Spearman's r = 0.9) with those of procrustes distance (not shown).

Computation of the amount of shape variation explained by treatment effects was performed in tpsRegr model (Rohlf 2004, tpsRegr v. 1.30) using procrustes distance, allowing a general measure of goodness of fit for the model (Goodall 1991).

Visualization of treatment effects on shape:

Klingenberg and Monteiro (2005) argue that premultiplying H, the discrimination matrix by E−, the pooled within-groups covariance matrix, should not be directly used to visualize estimated effects on shape, as generally used in discriminant or canonical variates analysis. Therefore the shape variables (partial warps and uniform components) were regressed onto treatment (genotype, sex, and background) effects, allowing visualizations of mean shape differences (Rohlf et al. 1996). The results were similar to a regression of shape onto the canonical variates (not shown). The regressions were performed in tpsRegr v. 1.30 (Rohlf 2004) and visualized using vector plots. The vectors describing shape differences were then imported into Adobe illustrator (V9.0 Adobe) where the wing was “drawn” to illustrate the wing shape. A caveat to this method is that procrustes superimposition of the landmarks can transfer variance across all landmarks, thus reducing the observed effect of genotype on shape if the difference is due to just a few coordinates. However, given that the effects of genotype, background, sex, and digitizing error are all included in the alignment, the variance transfer appeared to be minimal for any given effect.

Multivariate measures of environmental (residual) variation:

To determine whether the introgression of the mutations had a significant effect on the amount of phenotypic variation for wing shape, two related multivariate measures were used. The total variance, the sum of the variances for all 18 landmark coordinates, is computed as the trace of the covariance matrix (Tr(V)) or the sum of its corresponding eigenvalues,  (where λi = the ith eigenvalue). To further partition these effects, the coordinates corresponding to the proximal–distal and anterior–posterior axes were examined separately. In addition, the generalized variances for the landmark data were also investigated. The generalized variance is calculated as the determinant of the covariance matrix and includes information about the variances and covariances between landmarks (Rencher 1998). As the covariance between linear combinations of landmarks increases, the generalized variance should decrease relative to the total variance. Given that the procrustes superimposition results in a covariance matrix of less than full rank, the entire set of 18 coordinates could not be examined. However, since the determinant of the covariance matrix is equal to

(where λi = the ith eigenvalue). To further partition these effects, the coordinates corresponding to the proximal–distal and anterior–posterior axes were examined separately. In addition, the generalized variances for the landmark data were also investigated. The generalized variance is calculated as the determinant of the covariance matrix and includes information about the variances and covariances between landmarks (Rencher 1998). As the covariance between linear combinations of landmarks increases, the generalized variance should decrease relative to the total variance. Given that the procrustes superimposition results in a covariance matrix of less than full rank, the entire set of 18 coordinates could not be examined. However, since the determinant of the covariance matrix is equal to  , a subset of the first six eigenvalues was used, which explained between 85 and 90% of the variation from each covariance matrix. Similar results were obtained when all nonzero eigenvalues were included (not shown). This value was log transformed (

, a subset of the first six eigenvalues was used, which explained between 85 and 90% of the variation from each covariance matrix. Similar results were obtained when all nonzero eigenvalues were included (not shown). This value was log transformed ( ).

).

Cluster analysis:

To examine the relationships between the effects of mutations within genes on shape, aggregate hierarchical clustering was employed on the procrustes residuals for each landmark. Confidence in the clustering was assessed with the multiscale bootstrap resampling clustering algorithm (Shimodaira 2004) found in the pvclust package in R v. 2.1 (Ihaka and Gentleman 1996). A number of different distance metrics (Euclidean, Manhattan, and uncentered correlation) and agglomeration rules (Ward's, single, complete, UPGMA, and median) were used to scrutinize the robustness of the dendogram.

RESULTS

The effects of genetic background, sex, and mutant genotype on wing size:

Mutational effects on wing size were very limited as shown in the following analysis. Previous work demonstrates that many mutations can have a profound effect on overall body size (Chen et al. 1996; Potter et al. 2001), as well as on the size of particular structures (Halder et al. 1998; Dworkin 2005b). However, it is also clear that environmental conditions such as density and nutritional status during development can greatly affect body size. This appears to be the case in this study, since the full analysis demonstrates strong replicate effects on measures of centroid size (Table 2). In addition, visual examination of line means indicates that samples heterozygous for the mutant alleles are correlated with wild-type congenics from the same vial (r = 0.43, P < 0.002). One possible explanation for this correlation is that residual segregating variation in wild-type individuals exists as a result of the crosses to the heterogeneous backgrounds of the original mutant stocks. However, this source of variation is unlikely to be a significant factor, as “residual” line effects among wild types procured from crosses to each mutant did not contribute a significant amount of variation relative to the replicate effects (not shown). A more likely explanation that is consistent with residual effects of vial on size is the random variation in growth media quality or density effects.

To account for both the strong replicate effect and the possible genotype–environment correlation each replicate was analyzed separately, and wild-type and mutant individuals were compared from within a cross only. Using Fisher's method for combining probabilities (Sokal and Rohlf 1995, pp. 796–797), maintaining α = 0.05, corrected for 50 independent contrasts (P < 0.001), only five heterozygous mutants demonstrated a significant effect on wing centroid size for this critical value: omb, Gap1, bs, sbb, and Src42A (sequential Bonferroni did not change this result). Of these, both omb and bs demonstrated venation defects of moderate penetrance in the heterozygous state, making assessment of centroid size for the whole wing difficult. Individuals mutant for Src42A and sbb consistently demonstrated a decrease in centroid size, while mutations in Gap1 showed an increase. In general, it appears that when measured as heterozygotes, the mutations have only weak effects on wing size.

Mutations in the TGF-β and EGF signaling pathways have profound effects on wing shape:

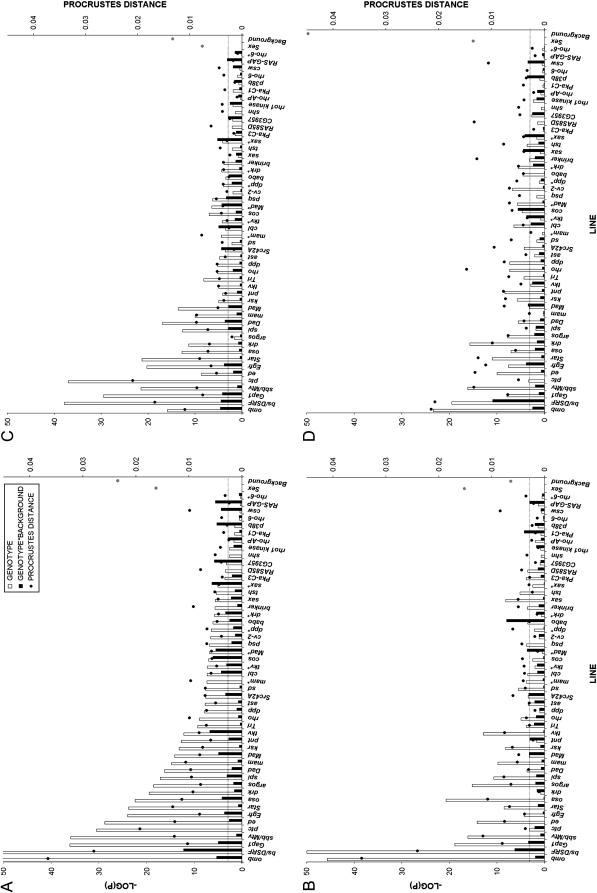

While the role of Dpp and EGF signaling has been well elucidated with respect to pattern formation and vein–intervein determination, little is known about how these genes affect shape. Of the sample of 50 mutations (representing 43 genes) measured in a heterozygous state, 44 of the mutations demonstrated either a direct effect of the mutant genotype (41/50) or an interaction between mutant genotype and genetic background (19/50) on the shape of the wing (Figure 2A). Examining the mutations separately by background and adjusting for an increase in number of contrasts (P = 0.0005 for α = 0.05) still lead to 43/50 mutations showing significant effects in at least one background, and 29/43 show significant effects in both backgrounds independently (supplemental Figure 1a at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). Of the seven genes represented in this sample by two independent insertions, both alleles showed significant effects on shape, except in the case of rho-6, where neither allele had a significant effect on shape (Figure 2).

Figure 2.—

Statistical association and effect size for mutations used in this study. (A) The effects of the mutation on wing shape for the whole wing blade, ordered by significance. (B–D) MANOVA for the anterior (B), central (C), or posterior (D) subregions of the wing. Horizontal axis: each mutation used in this study. Left vertical axis: negative log of the P-value from the MANOVA (Wilk's Λ). Right vertical axis: procrustes distance (PD) between the mean configurations of mutant from its wild type. Correcting for multiple contrasts using Bonferroni correction maintains α = 0.05 at −Log(P) = 3.0, represented by the horizontal line, while a nominal P = 0.05 is at −Log(P) = 1.3. * represents the alternative allele for that gene. Procrustes distances for both background and sex effects (shaded circles) are included at the end of each graph for comparative purposes.

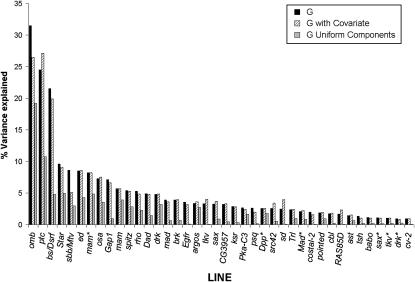

To examine the possibility of an allometric relationship between shape and size, the effects of genotype, sex, and genetic background were examined with and without centroid size as a covariate. Variation for shape covaried with wing size (not shown), but in general, excluding size as a covariate from the model did not alter the results with respect to the effect of the mutation on shape (Figure 3). This suggests that the genotypic effects on shape are independent of allometry with size. In contrast, the effects of sex on shape are in part a consequence of allometric covariation with size, and the sexual shape dimorphism is dependent on (sex-adjusted residual) size differences (Table 3). The effect of genetic background on shape also has a strong allometric component; however, a test for homogeneity of slopes rejected the null hypothesis for a common slope, suggesting different allometric relationships (interaction term between centroid size and background). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that there is a genotypic specific shape for the wing, independent of size (Birdsall et al. 2000).

Figure 3.—

Genotypic effects on shape are not sensitive to allometric scaling with size. Variance explained by genotype without centroid size in the model (labeled G, solid bars) or with centroid size as a covariate in the regression model (labeled G with covariate, hatched bars) is shown. For the majority of the mutations examined, including centroid size as a covariate in the model has negligible effects on the proportion of variation explained on the basis of Goodall's test on procrustes distance. In addition, the proportion of variation explained by genotype for the uniform components is shown (G uniform components, shaded bars), demonstrating that the shape change of many of the mutations is due to the effects of linear transformations.

TABLE 3.

Variance for shape explained

| Variance explained (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Model, no covariate | Model, CS as covariate | Sex effects using residual CS | Uniform components |

| Background × sex | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.0 | |

| Background | 30.85 | 23.55 | 0.34 | |

| Sex | 14.85 | 3.53 | 3.28 (28.1) | 1.67 |

| Centroid | 25.06 | 32.5 (7.7) | 2.34 | |

| N = 3705 | ||||

The amount of variation explained by regression of shape onto treatment effects is shown. The basic model does not include centroid size (CS) as a covariate and shows a large amount of variation explained by both background and sex. However, the sex effect is due in part to the covariate of size and when this is incorporated into the model. This effect is reduced when the residuals of centroid size (after taking sex into account) are used as a covariate, as shown in parentheses in the fourth column. The fifth column reports the variation explained for uniform components of shape (shearing and dilation), demonstrating a minor role for these effects.

Region-specific effects of mutations on wing shape:

To further assess the effects of the mutations on wing shape, variation in the displacement of the landmarks in the wing for the B, C, and D regions was separately aligned and analyzed. These regions are subdivided on the basis of the known properties of the developmental regulation in the wing (Birdsall et al. 2000; Palsson and Gibson 2000). In particular we can ask whether the effects of the mutations on shape are concordant with the known developmental roles of the genes. Interestingly, a number of mutations demonstrate region-specific effects (Figure 2, B–D). For instance, both alleles of downstream receptor of kinase (drk) and the allele for crossveinless-2 (cv-2) show no effect in the anterior (B) region, but a significant effect in the posterior (D) region of the wing (Figure 2B vs. 2D). Cv-2 is most strongly expressed in the posterior crossvein, and the loss of its function leads to loss of this structure (Conley et al. 2000). In contrast, both alleles of mastermind (mam), as well as scalloped (sd), spitz (spi), and others show no effect in the posterior region, but do so in the anterior region (Figure 2B vs. 2D). Not surprisingly, dpp shows its strongest effect in the central region of the wing, relative to the B and D regions. As discussed in the Introduction, Dpp protein forms a gradient with its highest levels being at the border of the anterior and posterior compartment in the center of the wing. One mutation that is of particular interest is spi, which shows a highly significant effect in the B and C, but not D regions. While spi is expressed throughout the wing, no previous observations were consistent with it having a role in wing development (Simcox 1997; Guichard et al. 1999; Zecca and Struhl 2002). The ability to discriminate such fine-scale differences makes wing shape a potentially powerful tool for elucidating genetic function.

While the mutations do show region-specific effects, it is worth highlighting the moderate, but significant correlation between the B and D regions on the basis of both procrustes and Mahalonobis distance (Spearman's r = 0.38, P < 0.01). Both the B and the D regions are also highly correlated to the central (C) region of the wing. This suggests that the effects of many mutations spread throughout the wing. This view is supported by examining the strength of the association between the mutations and shape for the whole wing vs. the distinct regions. For the majority of mutations, the observed effect is larger when all landmarks are considered, rather than for specific subsets. All else being equal, increasing the number of landmarks as dependent variables should decrease the statistical support, unless the additional variables are contributing to the treatment effect (Rencher 1993). This suggests that for many of the mutations, there are subtle effects over many of the landmarks.

In addition to the individual mutations having effects on wing shape, it is clear that the effect of the genetic background used for the introgressions can have profound effects on wing shape. As shown in supplemental Figure 2 (http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), the major axes of variation represented by principal components analysis are clearly separating genetic background and sex (supplemental Figure 2C), while the effects of individual mutations are relatively small (not shown). The effect of sex on shape appears to largely widen the distal region of the wing (supplemental Figure 2A). The two wild-type strains used for genetic backgrounds in this study, Ore-R and Sam, show complex shape differences predominantly involving displacement of landmarks along the proximal–distal axis (supplemental Figure 2B). These results are consistent with previous observations that show considerable natural genetic variation for shape.

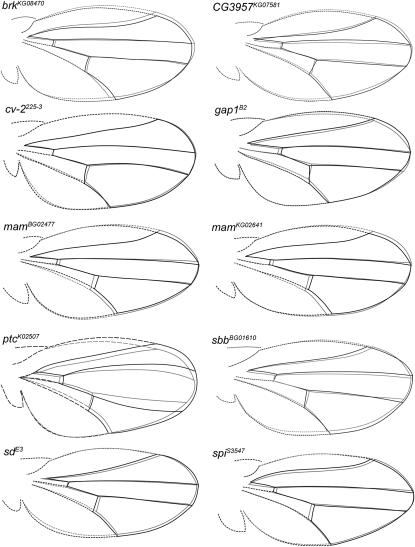

Visualizing the effects of mutations on shape:

To more thoroughly explore the particular effects that mutations have on shape, shape variables were regressed onto genotype for the purposes of visualization (Figure 4, supplemental Figure 3 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). Some genes such as mam appear to have an effect on landmark displacement throughout most of the wing with the two different mam alleles causing similar changes in shape. By contrast the mutation in cv-2 mostly shifts the position of the posterior crossvein relative to the wild type. The effect of the mutation in patched (ptc) is quite profound, with a widening of the central region of the wing relative to other landmarks, consistent with upregulation of Dpp signaling. However, most mutations have much more subtle effects on landmark displacement compared to the wild type. For instance, many of the mutations show considerable shape variation along the proximal–distal axis of the wing, especially in the more proximal region of the wing, as demonstrated by the relative displacement of the crossveins (Figure 4). Generally the landmarks for the anterior or posterior crossveins tend to shift in the same direction along the proximal–distal axis. However, some mutations in genes such as CG3957, Gap1, sbb, ed, and osa (Figure 4 and supplemental Figure 3) demonstrate that the landmarks of the posterior crossvein can shift independently of one another. These results demonstrate that while mutations generally have very broad effects across the whole wing, there is considerable independence for localized shifts in the position of landmarks.

Figure 4.—

The effects of mutations in the Egfr, Hedgehog, and TGF-β pathways on wing shape. The magnitude of the vectors describing the shape change is multiplied five times to facilitate visual examination of the shape change. For all illustrations, black represent the mean shape of the mutation, while gray represents the mean shape for the wild-type siblings from the relevant crosses. Solid segments represent estimated connections between landmarks sampled in this study. The dashed lines are used to illustrate the remaining wing morphology and are for illustrative purposes only.

One possible explanation for the effects observed across the whole wing is that the method of superimposition can result in artifactual landmark displacement. Procrustes superimposition is sensitive to relatively large deviation in position across a small number of landmarks. This can result in the “Pinocchio” effect where after superimposition the effects are transferred across all the landmarks and not just the ones showing displacement (Rohlf and Slice 1990; Walker 2000; Zelditch et al. 2004). This variance transfer can make it appear as if all landmarks are being displaced, when the biological effect is limited to just a few. However, the landmark displacements in this study are relatively small, and as shown for examples such as cv-2 (Figure 4) the Pinocchio effect is arguably negligible since the variation in landmarks is limited to the posterior crossvein. Indeed, superimposition with additional factors such as sex and background did not result in substantially different vectors describing the genotypic components of shape changes. Thus it is likely that the observed effects of the mutations on the shape of the whole wing are the result of biological factors.

One additional method to partition the shape variation is to examine uniform (affine) vs. nonuniform components (Rohlf and Bookstein 2003). The uniform components describe patterns of variation resulting from global linear transformations of the configuration, as opposed to localized effects (nonuniform). Uniform transformations keep all “lines” parallel when comparing the reference and target samples. The two uniform transformations of interest in the analysis of shape can be described as compression/dilation (such as making a square a rectangle) and shearing (transforming a square into a parallelogram). To examine whether the uniform components of shape were contributing to variation for shape, the amount of variation due to the uniform components was computed (Figure 3, shaded bars). For a considerable number of the mutations examined, at least half of the variation explained by the mutation was due to uniform components. Regression of uniform components onto genotype was concordant with this result, with both shearing and dilation contributing to varying degrees (not shown). Consistent with the multivariate analyses (Figure 2) it appears as if there are often global effects of the mutation on wing shape.

Egfr and TGF-β pathway genes do not separate on the basis of shape:

In general it is difficult to qualitatively group the effects of the mutations on shape. Therefore aggregate hierarchical clustering was used to examine which mutations tended to affect shape in similar ways. As expected, the mam alleles cluster together (supplemental Figure 4 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). However, the clustering of the mutations on the basis of shape does not result in a dendogram topology consistent with the prediction that mutations in genes from given genetic pathways having similar effects on shape. Often mutations in the same gene do not cluster together on the basis of shape differences. These results suggest that subtle changes in gene function may result in substantially different effects on shape, and quantitative cross-talk between pathways may be complex. One interesting observation is that the cluster at the far right of the dendogram, from cos to drk, has an excess of mutants that show venation defects as homozygotes (Table 1). It is unclear if this is suggestive of a relationship between venation defects as homozygotes and shape effects as heterozygotes, but merits further investigation. However, it is clear from the bootstrap estimates that the topology of the dendogram is not particularly robust, with the exception of the terminal nodes. Thus, unlike grouping genes together on the basis of qualitative mutant phenotypes, clustering on the basis of shape variables ought to be used with prudence.

Mutations do not increase the within-line variance for shape:

It is often assumed that mutations not only change mean trait expression value, but also increase the phenotypic variance for the trait (Waddington 1942), as has been observed in a number of experiments involving bristle and sex-comb teeth number (Dworkin 2005b,c). The increase in phenotypic variation can be due either to an increase in genetic variation (i.e., cryptic genetic variation) or to an increase in the environmental/residual variation. While there is considerable evidence for cryptic genetic variation, it is unclear if the increase in environmental variance is a general observation or the result of specific perturbations. Introgressing each of these mutations into otherwise isogenic backgrounds allows for a powerful test of the generality of this phenomenon over a large set of mutational perturbations. Since each wild-type line is isogenic, the residual variation is equivalent to the within-line variation. Thus the effects of each individual mutation can be compared to its wild-type congenics from a common environment to test for an increase in within-line variation.

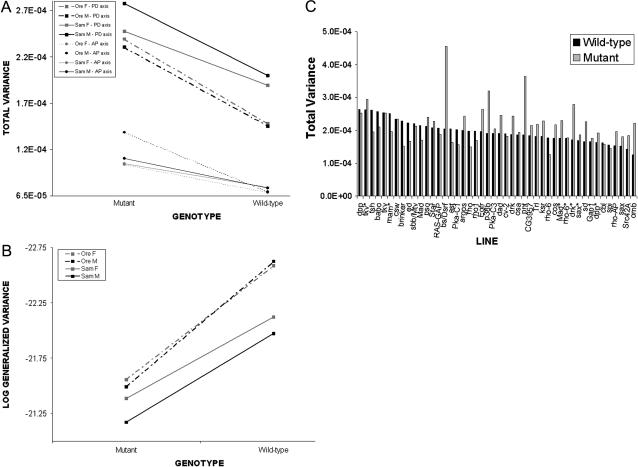

To examine this, two standard multivariate measures of variance were employed, the total variance (the sum of the variances across all landmarks) and the generalized variance, which includes a measure of covariation across variables (Rencher 1998). Overall, sex has a small effect that appears negligible, at least in the Ore background (Figure 5A). Mutants increase total variance between lines, and this increase is observed mostly along the proximal–distal, not the anterior–posterior, axis (Figure 5A). This result is a consequence of the different effects that each mutation has on shape relative to the wild type. However, when patterns of within-line variance are examined, there is not a universal increase in variation for each mutation, but large effects of particular mutations on the total variance (Figure 5C, supplemental Figure 5 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), with most showing no increase in total variance. The large increase in variance for mutant females in the Ore-R background is due to a few mutations like omb, which can shift landmark positions drastically due to mild delta-like venation defects. In general the picture from the generalized variance is quite similar to that of the total variance (Figure 5B, supplemental Figure 6 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), suggesting no major change in patterns of covariation between landmarks with regard to treatment effects. Thus, there is little evidence that an increase of within-line variance is a general observation due to perturbation by mutation for wing shape.

Figure 5.—

No general increase in within-line variation for wing shape due to genotype. Using two measures of multivariate variance, the total variance (A) and a measure of the generalized variance (B), there is evidence for an increase in variation due to the presence of the mutations relative to the wild type. (A) Interestingly, the amount of variation around landmarks is greater in the proximal–distal axis, relative to the anterior–posterior axis. (B) The generalized variance as measured by  for the first six eigenvalues (λi) shows a similar picture to that of the total variance. (C) The increase in variation is not due to a general increase in within-line variation, as can be seen by examining each mutation separately for males in the Ore-R background. In this instance, only 2 mutations, omb and bs, of the 50 used in this study are observed to increase the within-line variance for shape.

for the first six eigenvalues (λi) shows a similar picture to that of the total variance. (C) The increase in variation is not due to a general increase in within-line variation, as can be seen by examining each mutation separately for males in the Ore-R background. In this instance, only 2 mutations, omb and bs, of the 50 used in this study are observed to increase the within-line variance for shape.

Wing morphogenesis defect, a new gene showing defects in wing morphogenesis:

One P element used in this study represented a predicted transmembrane receptor protein serine/threonine kinase, CG3957 with no previously recognized function. The mutation in CG3957 showed a significant effect on shape (Figures 2 and 4) and as a homozygote showed wing morphogenesis defects consistent with improper lamination of the dorsal and ventral wing surfaces (supplemental Figure 7 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/), and on the basis of this phenotype we have provisionally named this gene wing morphogenesis defect (wmd). The putative location of the insertion in wmd is at 59E3 on the right arm of chromosome 2, situated close to the start site of the gene (supplemental Figure 7). However, the location of the wmd allele requires confirmation, and a detailed analysis of the function of this gene is necessary. More details about this mutant and its parent gene are discussed in the legend of supplemental Figure 7.

DISCUSSION

Wing shape as a model trait for quantitative developmental genetics:

While the qualitative pattern of wing venation in the melanogaster subgroup shows little variation, the relative placement and intersection of veins vary considerably (Houle et al. 2003). Despite the fact that wing shape has been the focus of much recent interest (Weber 1990; Weber et al. 1999, 2005; Birdsall et al. 2000; Palsson and Gibson 2000, 2004; Zimmerman et al. 2000; Houle et al. 2003; Dworkin et al. 2005; Mezey and Houle 2005; Mezey et al. 2005 ), quantitative genetic analysis for shape is still in its early stages. In this study, 50 mutations representing >40 candidate genes from the EGFR, Hedgehog, and TGF-β signal transduction pathways were examined as heterozygotes to determine what, if any effect these mutations have on shape. The vast majority of mutations examined show highly significant, although often subtle effects on wing shape when measured as heterozygotes, clearly demonstrating the link between wing development and the attainment of the final proportions of the wing. The mutations show a wide variety of effects on shape and demonstrate the relative sensitivity of shape as a model phenotype for genetic studies, even when measured in the heterozygous state. As one example of the power of this approach, we observed that a mutation in spi caused a shape change relative to its congenics. spi has been shown to be expressed ubiquitously in the imaginal wing disc during the third larval instar (Guichard et al. 1999; Zecca and Struhl 2002) and in the pro-veins of the pupal wing disc, but there has been no evidence for a large defect in the wing due to loss of spi function (Guichard et al. 1999; Zecca and Struhl 2002). It does appear that spi interacts synergistically with vestigial (vg), as trans-heterozygotes for mutants in both loci cause a severe notching phenotype of the wing, while individual heterozygotes for either mutation qualitatively have wild-type wings (Nagaraj et al. 1999). As shown here, individuals heterozygous for either spi or the vg protein-binding partner, sd exhibit subtle loss-of-function phenotypes for wing shape (Figures 2 and 4).

The benefit of this sensitivity is tempered by the recognition that as with most quantitative traits, effects such as genetic background must be carefully controlled for a high degree of confidence in the results (Norga et al. 2003). In this study, a few mutations had significant effects in only one of the two genetic backgrounds, and overall the main effect of genetic background was substantial in comparison to the effects of many individual mutations (Figure 2). Some work suggests that wing shape shows a relatively low environmental sensitivity relative to wing size. However, in genetic screens for novel mutations affecting quantitative trait variation it is important to control the rearing environment, so that treatment variance is maximized relative to residual effects. Furthermore, it must be considered that shape is inherently multivariate while size is generally measured in a univariate context. If each variable is providing some unique information, then the multivariate approach will be much more powerful for detecting subtle effects. The evidence in this study suggests that for most mutations, each landmark contributes a small but significant effect. Thus, multivariate approaches provide powerful tools for examining genetic effects in this context.

Genotypic effects on shape are invariant with respect to size allometry:

One general finding of particular interest is that the effects of the P-element mutations on wing shape were not sensitive to scaling effects with size. This was observed both in terms of the magnitude of the genotype–shape association not being altered due to the inclusion of size as a covariate in the model as well as with regard to the amount of variation that genotype explains for shape. This is somewhat surprising given that genotype (mutant vs. wild type) generally explained a small fraction of the variation in shape, varying between 1 and 30% (Figure 3), as compared to size, sex, and genetic background (Table 3). Interestingly, the effect of sex on shape was in part a consequence of allometry with size (Table 3, supplemental Figure 2C at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). A previous study that examined the association between a naturally occurring polymorphism in Egfr with wing shape also observed that while allometric effects of size on shape were highly significant, they had minimal impact on the genotypic association (Dworkin et al. 2005). This suggests that there is an invariant genotypic component to shape regardless of size. While size-related traits are highly sensitive to uncontrolled environmental variance, wing shape is relatively robust (Birdsall et al. 2000; Klingenberg and Zaklan 2000; Santos et al. 2005).

Mutations tend to affect the shape of the whole wing:

While it is clear that some of the mutations show region-specific effects, in general they appear to affect the displacement of landmarks across the whole wing (Figures 2 and 4). Given the known function of many of these genes during wing development, these results may be difficult to reconcile. For instance, in the late third instar wing imaginal disc brk is expressed in the most anterior and posterior, but not in the central region of the wing imaginal disc (Cook et al. 2004). Yet the mutation in brk demonstrates a significant effect on shape in each of the B, C, and D regions (Figure 2, B–D, Figure 4). What are the possible biological explanations for these observations? It may perhaps be the result of as yet unknown direct effects of particular genes in those developmental regions. For example, brk could be functioning in the central region of the wing disc at other stages of development. TGF-β signaling plays a crucial role in the patterning of the anterior–posterior axis of the wing imaginal disc and is then reutilized during pupal development with respect to the maintenance of the longitudinal veins and initiation of crossveins (Yu et al. 1996; de Celis 1997; Ralston and Blair 2005; Serpe et al. 2005; Shimmi et al. 2005; Vilmos et al. 2005). Indeed, recent work has shown that brk is expressed in the intervein regions 24–28 hr after pupal formation, and its overexpression in the pro-vein regions suppresses vein fates (Sotillos and De Celis 2005). Thus the analysis of wing shape itself may provide new insight into previously unknown pleiotropic functions of some genes.

An alternative explanation for global effects on wing shape is that they result from the indirect developmental effects of the mutations. The majority of the genes that were examined in this study are highly pleiotropic and have demonstrated roles in numerous developmental events. Therefore it is plausible that the effects on wing shape are a consequence of systematic changes in development, which indirectly influence, but are not the result of, changes in wing development sensu strictu. Examples of such effects include changes in hormone production or response. However, it is worth noting that the results of this study are inconsistent with the indirect effects being linked to changes in overall body size, given that genotypic effects on shape are invariant to allometric scaling with size (Figure 3). One particular indirect effect worth considering is competitive growth between cell populations (Klingenberg and Nijhout 1998; Nijhout and Emlen 1998). In this scenario, changes in the patterns of growth in one region of the wing imaginal disc are compensated for in other regions, resulting in global shape changes in the wing. This type of indirect effect could be studied using clonal analysis in Drosophila to distinguish it from possible direct effects.

It was also shown that the uniform components, which describe global, linear patterns of transformation, contribute to the mutational effects of wing shape (Figure 3). While this is often the case in the analysis of shape, it is worth considering whether the uniform components of shape can help describe interesting developmental patterns or are simply a mathematical partition of the data. It is plausible that the uniform components may describe the effects of gradients of gene activity across the wing.

Is there concordance between gene function during development and its effect on shape?

While it is clear that most of the mutations show statistically significant effects, it is important to address whether the effects are biologically interpretable. Given that there is considerable information about the developmental roles of most of the genes used in this study, this does allow for some straightforward hypotheses to be generated about the presumed effect of the mutation on shape. Indeed, loss of function for ptc increases Dpp expression that can be expected to cause a widening of the central region of the wing (Sanicola et al. 1995), which is what is observed here (Figure 4). Cv-2, an extracellular TGF-β signaling modulator, shows only loss of the posterior crossvein (and the anterior crossvein with low penetrance) (Conley et al. 2000). The mutation used in the present study recapitulates the loss of crossvein phenotype as a homozygote (Table 1), and as a heterozygote the effect on wing shape is almost entirely localized to a displacement of the posterior crossvein (Figure 4). Thus, this does suggest that the effect of some mutations on shape is concordant with their known developmental roles.

Nevertheless, with the majority of the mutations examined in this study, their effects on shape are complex, include most of the landmarks, and often involve shifts in both the anterior–posterior and proximal–distal axes. When it is considered that the genes investigated in this study have been demonstrated to form complex genetic networks with cross-talk between pathways (Crozatier et al. 2002; Yan et al. 2004) as well as having multiple roles involved with patterning, growth, and vein determination, it is not surprising that it is difficult to predict the exact effect that the mutations will have on a complex multivariate phenotype such as shape. Indeed this may be a partial explanation as to why the cluster dendogram is not generally concordant with the genetic pathways (supplemental Figure 4 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). An alternative explanation for these results is that since the effects of these mutations likely range from weak hypomorphs to potential null alleles, the quantitative differences between alleles will result in very different effects on shape. Thus future studies should examine a variety of allelic effects for any given mutation (within a common isogenic background) to help investigate these possibilities.

The effects of mutation on levels of within-line variation:

It is commonly observed that many mutations change not only the mean value of a trait, but also its level of variation (Waddington 1957; Dworkin 2005a). For example, introgression of the bristle mutation Sternopleural increased levels of genetic, environmental, and within-individual variation (Dworkin 2005c). While this increase in overall levels of within-line variation is considered to be a general phenomenon (Waddington 1942), it has not been explicitly tested. The design of the current study allows for a test of this assumption across a large number of mutant genotypes. While there was evidence of an increase in the levels of the total variance of the mutant genotypes relative to their wild-type congenics, it was not the result of an effect of each mutation, but the result of large increases in variation for a small number of mutations (Figure 5C, supplemental Figure 3 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). It is unclear why there is a difference between the expected increase in variance generally and the observations here. It is unlikely that it is an artifact of the superimposition process, given that variance transfer across landmarks results in the same absolute levels for the total variance. Is this inconsistency the result of the complex biology of shape? In a series of studies on morphological integration in mutant vs. wild-type mice, similarly mixed results were observed, with increase in variance being observed for some, but not all mutations (Hallgrimsson et al. 2004, 2005). An additional explanation is that the mutations were examined in the heterozygous state in the current study and thus represent relatively “small” perturbations, unlike those used in other studies that had more profound phenotypic consequences (Dworkin 2005c). With respect to models of canalization, those mutations examined in the current study would be considered within the “zone” where canalization is operating and thus are relatively well buffered. Work examining the effects of mutations in the Hsp83 gene on bristle traits has observed changes in trait means without altering variances (Milton et al. 2003, 2005). However, it is clear that this question requires further examination using rigorous approaches and sufficient controls to minimize uncontrolled variance (Dworkin 2005a).

The developmental genetics of wing shape:

While there is a vast literature with respect to the development of the wing (Held 2002), only recently have the final proportions of the wing become a topic of research interest. The results from this study clearly demonstrate a role for those genes involved with wing development in shape itself. However, it is clear that the potential number of genes that affect shape may be quite large and reflects a diverse array of developmental and physiological processes that may not have been as well studied (Weber et al. 2005). For instance, it appears that orientation of cell divisions during wing disc development may play a role in the final proportions of the adult wing and that genes regulating planar polarity are associated with changes in both the orientation of cell divisions and wing shape (Baena-Lopez et al. 2005). In addition, the insulin signaling pathway appears to play a substantial role in regulating growth and modulating nutritional cues and may be an excellent candidate pathway for its effects on shape. Thus the combination of quantitative approaches to examining shape with mutational and developmental analysis will provide excellent tools for the future dissection of the genetics of wing shape as a model trait.

Acknowledgments

We thank Arnar Palsson and Miriam Zelditch for discussions related to this study, Nolen Morton and Laura Roten for help with wing dissections, and Alex Wolf for suggesting the name for wmd. Lisa Goering, Arnar Palsson, and two anonymous reviewers provided beneficial comments on a previous draft of this manuscript. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM616DD to G.G.) and by a National Science and Engineering Research Council (Canada) postdoctoral fellowship to I.D.

References

- Anholt, R. R., R. F. Lyman and T. F. Mackay, 1996. Effects of single P-element insertions on olfactory behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 143: 293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah, J., I. Dworkin, U. Cheung, A. Greene, B. Ing et al., 2004. The environmental and genetic regulation of obake expressivity: morphogenetic fields as evolvable systems. Evol. Dev. 6: 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Lopez, L. A., A. Baonza and A. Garcia-Bellido, 2005. The orientation of cell divisions determines the shape of Drosophila organs. Curr. Biol. 15: 1640–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall, K., E. Zimmerman, K. Teeter and G. Gibson, 2000. Genetic variation for the positioning of wing veins in Drosophila melanogaster. Evol. Dev. 2: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein, F. L., 1991. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data: Geometry and Biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Brower, D. L., 1986. Engrailed gene expression in Drosophila imaginal discs. EMBO J. 5: 2649–2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, D. L., 2002. A randomization-test wrapper for SAS PROC's, pp. 1–4 in SUGI. SAS, Orlando, FL.

- Chen, C., J. Jack and R. S. Garofalo, 1996. The Drosophila insulin receptor is required for normal growth. Endocrinology 137: 846–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, B., E. A. Wimmer and S. M. Cohen, 1991. Early development of leg and wing primordia in the Drosophila embryo. Mech. Dev. 33: 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley, C. A., R. Silburn, M. A. Singer, A. Ralston, D. Rohwer-Nutter et al., 2000. Crossveinless 2 contains cysteine-rich domains and is required for high levels of BMP-like activity during the formation of the cross veins in Drosophila. Development 127: 3947–3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, O., B. Biehs and E. Bier, 2004. brinker and optomotor-blind act coordinately to initiate development of the L5 wing vein primordium in Drosophila. Development 131: 2113–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozatier, M., B. Glise and A. Vincent, 2002. Connecting Hh, Dpp and EGF signalling in patterning of the Drosophila wing; the pivotal role of collier/knot in the AP organiser. Development 129: 4261–4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozatier, M., B. Glise and A. Vincent, 2004. Patterns in evolution: veins of the Drosophila wing. Trends Genet. 20: 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis, J. F., 1997. Expression and function of Decapentaplegic and thick veins during the differentiation of the veins in the Drosophila wing. Development 124: 1007–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Celis, J. F., 2003. Pattern formation in the Drosophila wing: the development of the veins. BioEssays 25: 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, I., 2005. a Canalization, cryptic variation and developmental buffering: a critical examination and analytical perspective, pp. 131–158 in Variation, edited by B. Hallgrimsson and B. K. Hall. Academic Press, London.

- Dworkin, I., 2005. b Evidence for canalization of Distal-less function in the leg of Drosophila melanogaster. Evol. Dev. 7: 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, I., 2005. c A study of canalization and developmental stability in the sternopleural bristle system of Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 59: 1500–1509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, I., A. Palsson, K. Birdsall and G. Gibson, 2003. Evidence that Egfr contributes to cryptic genetic variation for photoreceptor determination in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 13: 1888–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, I., A. Palsson and G. Gibson, 2005. Replication of an Egfr-wing shape association in a wild-caught cohort of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 169: 2115–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bellido, A., and P. Santamaria, 1972. Developmental analysis of the wing disc in the mutant engrailed of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 72: 87–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, G., and D. S. Hogness, 1996. Effect of polymorphism in the Drosophila regulatory gene Ultrabithorax on homeotic stability. Science 271: 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, G., and S. van Helden, 1997. Is function of the Drosophila homeotic gene Ultrabithorax canalized? Genetics 147: 1155–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, C., 1991. Procrustes methods in the statistical analysis of shape. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 53: 285–339. [Google Scholar]

- Guichard, A., B. Biehs, M. A. Sturtevant, L. Wickline, J. Chacko et al., 1999. rhomboid and Star interact synergistically to promote EGFR/MAPK signaling during Drosophila wing vein development. Development 126: 2663–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder, G., P. Polaczyk, M. E. Kraus, A. Hudson, J. Kim et al., 1998. The Vestigial and Scalloped proteins act together to directly regulate wing-specific gene expression in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 12: 3900–3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgrimsson, B., C. J. Dorval, M. L. Zelditch and R. Z. German, 2004. Craniofacial variability and morphological integration in mice susceptible to cleft lip and palate. J. Anat. 205: 501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgrimsson, B., J. Brown and B. K. Hall, 2005. The study of phenotypic variability: an emerging research agenda for understanding the developmental-genetic architecture underlying phenotypic variation, pp. 525–551 in Variation: A Central Concept in Biology, edited by B. Hallgrimsson and B. K. Hall. Elsevier, London.

- Held, L. I., Jr., 2002. Imaginal Discs: The Genetic and Cellular Logic of Pattern Formation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

- Hidalgo, A., 1994. Three distinct roles for the engrailed gene in Drosophila wing development. Curr. Biol. 4: 1087–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle, D., J. Mezey, P. Galpern and A. Carter, 2003. Automated measurement of Drosophila Wings. BMC Evol. Biol. 3: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka, R., and R. Gentleman, 1996. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5: 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg, C. P., 2002. Morphometrics and the role of the phenotype in studies of the evolution of developmental mechanisms. Gene 287: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg, C. P., and L. R. Monteiro, 2005. Distances and directions in multidimensional shape spaces: implications for morphometric applications. Syst. Biol. 54: 678–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg, C. P., and H. F. Nijhout, 1998. Competition among growing organs and developmental control of morphological asymmetry. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 265: 1135–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg, C. P., and S. D. Zaklan, 2000. Morphological integration between development compartments in the Drosophila wing. Evolution 54: 1273–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P. A., and G. Morata, 1976. Compartments in the wing of Drosophila: a study of the engrailed gene. Dev. Biol. 50: 321–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, T. F., R. F. Lyman and M. S. Jackson, 1992. Effects of P-element insertions on quantitative traits in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 130: 315–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F. A., A. Perez-Garijo, E. Moreno and G. Morata, 2004. The Brinker gradient controls wing growth in Drosophila. Development 131: 4921–4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey, J., and D. Houle, 2005. The dimensionality of genetic variation for wing shape in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 59: 1027–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey, J. G., D. Houle and S. V. Nuzhdin, 2005. Naturally segregating quantitative trait loci affecting wing shape of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 169: 2101–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton, C. C., B. Huynh, P. Batterham, S. L. Rutherford and A. A. Hoffmann, 2003. Quantitative trait symmetry independent of Hsp90 buffering: distinct modes of genetic canalization and developmental stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 13396–13401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton, C. C., P. Batterham, J. A. McKenzie and A. A. Hoffman, 2005. Effect of E(sev) and Su(Raf) Hsp83 mutants and trans-heterozygotes on bristle trait means and variation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 171: 119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj, R., A. T. Pickup, R. Howes, K. Moses, M. Freeman et al., 1999. Role of the EGF receptor pathway in growth and patterning of the Drosophila wing through the regulation of vestigial. Development 126: 975–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout, H. F., and D. J. Emlen, 1998. Competition among body parts in the development and evolution of insect morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 3685–3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norga, K. K., M. C. Gurganus, C. L. Dilda, A. Yamamoto, R. F. Lyman et al., 2003. Quantitative analysis of bristle number in Drosophila mutants identifies genes involved in neural development. Curr. Biol. 13: 1388–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palsson, A., and G. Gibson, 2000. Quantitative developmental genetic analysis reveals that the ancestral dipteran wing vein prepattern is conserved in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Genes Evol. 210: 617–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palsson, A., and G. Gibson, 2004. Association between nucleotide variation in Egfr and wing shape in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 167: 1187–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palsson, A., J. Dodgson, I. Dworkin and G. Gibson, 2005. Tests for the replication of an association between Egfr and natural variation in Drosophila melanogaster wing morphology. BMC Genet. 6: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podos, S. D., and E. L. Ferguson, 1999. Morphogen gradients: new insights from DPP. Trends Genet. 15: 396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaczyk, P. J., R. Gasperini and G. Gibson, 1998. Naturally occurring genetic variation affects Drosophila photoreceptor determination. Dev. Genes Evol. 207: 462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, C. J., H. Huang and T. Xu, 2001. Drosophila Tsc1 functions with Tsc2 to antagonize insulin signaling in regulating cell growth, cell proliferation, and organ size. Cell 105: 357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston, A., and S. S. Blair, 2005. Long-range Dpp signaling is regulated to restrict BMP signaling to a crossvein competent zone. Dev. Biol. 280: 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rencher, A. C., 1993. The contribution of individual variables to Hotelling's T2, Wilks' Λ and R2. Biometrics 49: 479–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rencher, A. C., 1998. Multivariate Statistical Inference and Applications. Wiley-Interscience, New York.

- Rohlf, F. J., 2003. tpsDig, digitize landmarks and outlines, Version 1.39. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY.

- Rohlf, F. J., 2004. tpsRegr, shape regression, Version 1.3. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY.

- Rohlf, F. J., and F. L. Bookstein, 2003. Computing the uniform component of shape variation. Syst. Biol. 52: 66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf, F. J., and D. E. Slice, 1990. Extensions of the procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst. Zool. 39: 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf, F. J., A. Loy and M. Corti, 1996. Morphometric analysis of old world talpidae (Mammalia, Insectivora) using partial-warp scores. Syst. Biol. 45: 344–362. [Google Scholar]

- Sanicola, M., J. Sekelsky, S. Elson and W. M. Gelbart, 1995. Drawing a stripe in Drosophila imaginal disks: negative regulation of Decapentaplegic and patched expression by Engrailed. Genetics 139: 745–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M., P. F. Iriarte and W. Cespedes, 2005. Genetics and geometry of canalization and developmental stability in Drosophila subobscura. BMC Evol. Biol. 5: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpe, M., A. Ralston, S. S. Blair and M. B. O'Connor, 2005. Matching catalytic activity to developmental function: tolloid-related processes Sog in order to help specify the posterior crossvein in the Drosophila wing. Development 132: 2645–2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimmi, O., A. Ralston, S. S. Blair and M. B. O'Connor, 2005. The crossveinless gene encodes a new member of the Twisted gastrulation family of BMP-binding proteins which, with Short gastrulation, promotes BMP signaling in the crossveins of the Drosophila wing. Dev. Biol. 282: 70–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimodaira, H., 2004. Approximately unbiased tests of regions using multistep-multiscale bootstrap resampling. Ann. Stat. 32: 2616–2641. [Google Scholar]

- Simcox, A., 1997. Differential requirement for EGF-like ligands in Drosophila wing development. Mech. Dev. 62: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal, R. R., and F. J. Rohlf, 1995. Biometry. W. H. Freeman, New York.

- Sotillos, S., and J. F. De Celis, 2005. Interactions between the Notch, EGFR, and Decapentaplegic signaling pathways regulate vein differentiation during Drosophila pupal wing development. Dev. Dyn. 232: 738–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata, T., and T. B. Kornberg, 1994. Hedgehog is a signaling protein with a key role in patterning Drosophila imaginal discs. Cell 76: 89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilmos, P., R. Sousa-Neves, T. Lukacsovich and J. L. Marsh, 2005. crossveinless defines a new family of Twisted-gastrulation-like modulators of bone morphogenetic protein signalling. EMBO Rep. 6: 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, C. H., 1942. The canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 150: 563. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, C. H., 1957. The Strategy of the Genes. Allen & Unwin, London.

- Walker, J. A., 2000. Ability of geometric morphometric methods to estimate a known covariance matrix. Syst. Biol. 49: 686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K., R. Eisman, L. Morey, A. Patty, J. Sparks et al., 1999. An analysis of polygenes affecting wing shape on chromosome 3 in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 153: 773–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K., N. Johnson, D. Champlin and A. Patty, 2005. Many P-element insertions affect wing shape in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 169: 1461–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K. E., 1990. Selection on wing allometry in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 126: 975–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]