SUMMARY

Many recovering substance users report quitting drugs because they wanted a better life. The road of recovery is the path to a better life but a challenging and stressful path for most. There has been little research among recovering persons in spite of the numbers involved, and most research has focused on substance use outcomes. This study examines stress and quality of life as a function of time in recovery, and uses structural equation modeling to test the hypothesis that social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning, and 12-step affiliation buffer stress toward enhanced life satisfaction. Recovering persons (N = 353) recruited in New York City were mostly inner-city ethnic minority members whose primary substance had been crack or heroin. Longer recovery time was significantly associated with lower stress and with higher quality of life. Findings supported the study hypothesis; the ‘buffer’ constructs accounted for 22% of the variance in life satisfaction. Implications for research and clinical practice are discussed.

Keywords: Recovery, addiction, 12-step, spirituality, social support, quality of life, meaning

Two of the reasons frequently cited by alcohol and other drug users for seeking recovery are negative consequences of drug use (past consequences and fear of future consequences) and “wanting a better life” (e.g., Laudet, Savage, & Mahmood, 2002; also see Burman, 1997). Several researchers have noted that the process of recovery is often precipitated by a combination of avoidance-oriented and approach-oriented goals (Walters, 2000; also see Granfield & Cloud, 2001). Although there has been little research in this area, what empirical evidence there is suggests that quality of life among active drug users is very poor and that stress levels are high. The road of recovery is both the path to and the promise of a better life. Recovery is a continuous, lifelong process and a difficult path for most (Flynn, Joe, Broome, Simpson, & Brown, 2003; Margolis, Kilpatrick, & Mooney, 2000). So, does recovery lead to a better life? As recently noted by White (2004), the problems created by excessive alcohol and drug use are well documented, but there is no comparable body of research on the recovery benefits that accrue to individuals, families and communities. Little research has been conducted in the recovering community; most of what is known of the recovery process emanates from treatment evaluations using short follow-up periods. The few empirical investigations conducted on recovery are typically exploratory, qualitative and methodologically limited (e.g., small sample size and/or restricted sample characteristics). There is a critical need for knowledge about the process of addiction recovery, about the challenges, about useful resources as well as about the positive outcomes of recovery. Such knowledge can provide recovering persons, their families and service professionals with realistic expectations for recovery outcomes, knowledge about the timeframes within which such outcomes are likely to be achieved, and the strategies and processes through which they are facilitated. To maximize its usefulness, research on recovery must use state of the art methodology including large representative samples, quantitative methods and sophisticated statistical techniques that help elucidate the critical processes at work (White, 2004). The present study is a first step in that direction. We examine stress and life satisfaction among recovering persons, and investigate the role of social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning, and 12-step affiliation as recovery capital–buffering stress and enhancing life satisfaction.

STRESS

Stress is closely linked to substance abuse; alcohol and drug use are regarded by some as self-treatment for existential pain (Ventegodt, Merrick, & Andersen, 2003). A recent teen survey found that high stress teens are twice as likely as low stress teens to smoke, drink, get drunk and use illegal drugs (The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2003). The multiple negative consequences of substance use, that may include poor physical and mental health, financial difficulties, homelessness, criminal justice involvement, and estrangement from family and friends, suggest that stress levels are very high among active users. Stress is also cited often as a relapse trigger (e.g., Laudet, Magura, Vogel, & Knight, 2004; Titus, Dennis, White, Godley, Tims, & Diamond., 2002). Virtually nothing is known about stress levels among recovering persons. A cross-sectional study of 102 women in recovery reported that perceived stress in 16 life domains significantly decreased from pre-recovery to recovery (Weaver, Turner, & O’Dell, 2000). An informative, albeit small-scale, exploratory study of drug-dependent persons abstinent for an average of 9 years speaks to the demands recovery places on the individual (Margolis, Kilpatrick, & Mooney, 2000): the majority of subjects reported passing through an initial phase (lasting one to three years) almost solely focused on remaining abstinent, particularly the first year (early recovery). Only once a solid recovery foundation was established could subjects concentrate on “living a normal life,” where abstinence was no longer the main focus. That middle recovery phase was a transitional period involving a conscious decision to change life focus: after years of addiction centered on drug use and a period focused on remaining abstinent, the addict is left with “well, what do I do now?” (Chapman, 1991, p. 11). Following that transitional period, the addict enters late recovery, a time of individual growth and search for meaning (Freyer-Rose, 1991). Each of these phases presents new challenges, responsibilities, and potential sources of stress.

QUALITY OF LIFE

Quality of life (QOL) has become an important endpoint in clinical trials and studies for many chronic disorders, but has not been widely studied in the substance abuse field (Smith & Larson, 2003). The QOL construct is an important diagnostic and outcome criterion because it incorporates the individual’s subjective view and informs on the living situation of a given population (Rudolf & Watts, 2002). In the addiction field, the few studies available have been conducted mostly on restricted populations–e.g., heroin users, clients in substance abuse treatment and HIV-positive individuals. In particular, individuals abusing crack cocaine have rarely been studied (Rudolf & Watts, 2002). Findings from existing studies suggest that QOL among substance users is poor (e.g., Te Vaarwerk & Gaal, 2001). This is especially true of drug injectors and of users of ‘hard’ drugs such as cocaine, heroin and amphetamines (Brogly, Mercier, Bruneau, Palepu, & Franco, 2003; Havassy & Arns, 1998; Ventegodt & Merrick, 2003). A recent study reported that QOL among substance abuse treatment patients receiving public assistance was significantly lower than for the general population, and as low or lower as that of patients with other serious chronic disorders and health conditions such as lung disease and diabetes; addiction treatment clients’ QOL was significantly lower than that of individuals interviewed one week prior to cardiac surgery (Smith & Larson, 2003). Quality of life among active substance users is negatively associated with frequency of use and with the drug composite score of Addiction Severity Index (ASI–McLellan, Cacciola, Kushner, Peters, Smith, & Pettinati, 1992; e.g., Falk, Wang, Carson, & Siegal, 2000). Very little is known about the association between recovery and QOL; one study reported that QOL increased among recovering alcohol users whereas it decreased among those who relapsed (Foster, Marshall, & Peters, 2000). To date, the relationship between length of abstinence and life satisfaction remains unclear (Rudolf & Watts, 2002).

Overall, available evidence suggests that alcohol and other drug users are under high levels of stress and that QOL is poor. Little is currently known of QOL as a function of recovery. In the next section, we review briefly a number of factors that have been found to buffer stress and to enhance quality of life and/or recovery from addictions; they are: social supports, spirituality, life meaning, religiousness, and affiliation with 12-step fellowships.

SOCIAL SUPPORTS

Granfield and Cloud (2001) recently noted that “though we live in a society that glorifies a meritocratic ideology of ‘pulling oneself up by the bootstrap,’ it is largely a cultural myth” (p. 1566). The importance of social support in influencing behavior has been shown in a large number of different contexts. Social relationships are hypothesized to be helpful in two ways: indirectly by buffering stress in difficult times, and directly, by providing assistance, emotional support and a sense of belonging that can alleviate or buffer stress as well as improve satisfaction with life, whether or not stress is present (Caplan & Caplan, 2000; Dalgard & Tambs, 1997). A large body of literature has elucidated the mechanisms through which social support promotes physical and mental health and buffers psychological stresses (Greenblatt, Becerra, & Serafetinides, 1982; Taylor & Aspinwall, 1996; for a review, see Taylor, 1995). Empirical evidence has linked social support to increased health, happiness and longevity (Berkman, 1985; Lin, 1986). Among substance users, lower levels of social support prospectively predict relapse (Havassy, Hall, & Wasserman, 1991) while higher levels predict decreased substance use (Humphreys & Noke 1997; Noone, Dua, & Markham, 1999; Rumpf, Bischof, Hapke, Meyer, & John, 2002; for review, see El-Bassel, Duan-Rung, & Cooper, 1998). Moreover, social support has been linked to better quality of life both among substance users and individuals with a mental disorder (e.g., Brennan & Moos, 1990; Nelson, 1992) and is a significant correlate of subjective well-being among recovering substance users who are dually-diagnosed with comorbid psychiatric disorder (Laudet et al., 2000).

While general friendship is important for overall well-being, specific domains are predicted more strongly by the behavior and orientation of one’s social network (e.g., Beattie & Longabaugh, 1997). Alemi and colleagues demonstrated empirically the importance of the orientation of social support networks and noted “that people are likely to adopt roles supported by the individuals who they see most often and whose opinions are important to them” (Alemi, Stephens, Llorens, Schaefer, Nemes, & Arendt, 2003, p. 1294). In the addiction field, recovery-oriented support may foster greater self-efficacy toward ongoing abstinence because recovering persons can acquire effective coping strategies from their peers (e.g., Finney, Noyes, Coutts, & Moos, 1998). Support, and in particular, recovery-oriented support, is likely to be critical to alcohol and other drug users, especially early on, as there is evidence that friendships erode with the cessation of substance use–in all likelihood because the individual is moving away from substance using associates but may not have yet developed a healthier network (e.g., Ribisl, 1997). Friends’ support for substance use is a negative predictor of abstinence (e.g., Havassy, Wasserman, & Hall, 1993; Longabaugh et al., 1998; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997). Conversely, having a recovery-oriented network predicts subsequent decreased alcohol use (e.g., Humphreys, Moos, & Cohen, 1997; Humphreys, Mankowski, Moos, & Finney, 1999; Weisner, Delucchi, & Matzger, 2003). Many former recovering persons report that being in the company of other recovering individuals is helpful (e.g., Granfield & Cloud, 2001; Margolis et al., 2000; Nealon-Woods, Ferrari, & Jason, 1995; Richter, Brown, & Mott, 1991; Trumbetta Mueser, Quimby, Bebout, & Teague 1999). At least one study has reported that the effect of support for abstinence on reduced substance use was stronger than that for general friendship quality (Humphreys et al., 1999).

SPIRITUALITY, RELIGIOUSNESS AND LIFE MEANING

Human beings have long looked to faith for strength and support, particularly in difficult times. Scientific research and clinical practice were slow to acknowledge and to investigate the role of this dimension of the human experience, in large part because it is not easily defined or captured using traditional quantitative measures. In the last twenty years and especially in the last ten years, several groups of researchers have developed and tested instruments to assess the constructs of religiosity and spirituality, contributing to refined definitions of the terms and to a growing understanding of their critical importance in clinical research and practice. A large body of empirical research has investigated the role religion and spirituality play in people’s lives, particularly but not only, in the lives of individuals struggling with chronic and terminal illness.

Before proceeding with a brief overview of the literature, working definitions of key terms are in order. Cook (2004) recently surveyed 265 published works on spirituality and addiction and concluded that “spirituality as understood within the addiction field is currently poorly defined” (p. 539). In this paper, we adopt the definitions put forth by the Fetzer Institute in preparation for developing a multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality1999:

Religiousness has specific behavioral, social, doctrinal, and denominational characteristics because it involves a system of worship and doctrine that is shared within a group. Spirituality is concerned with the transcendent, addressing ultimate questions about life’s meaning, with the assumption that there is more to life than what we see or fully understand. (…) While religions aim to foster and nourish the spiritual life–and spirituality is often a salient aspect of religious participation–it is possible to adopt the outward forms of religious worship and doctrine without having a strong relationship to the transcendent. (p. 2)

Although other definitions have been proposed, they generally preserve the essential distinction between the two concepts (e.g., Elkins, Hedstrom, Hughes, Leaf, & Saunders, 1988; Corrigan, McCorkle, Schell, & Kidder, 2003; The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2001; for review, see Cook, 2004). As the above definitions suggest, spirituality is generally thought of as more basic, more inclusive and more universal than is religiousness; spirituality is a subjective experience that exists both within and outside of traditional religious systems (Vaughan, 1998). Spirituality and religiousness are both latent (multidimensional) constructs that can include behavioral, cognitive, existential, spiritual, ritualistic and social components (Connors, Tonigan, & Miller, 1996; Miller & Thoresen, 2003). Religiousness and spirituality are generally conceptualized as overlapping but distinguishable constructs that share some characteristics but retain non-shared featured (e.g., Miller & Thoresen, 2003; Zinbauer, Pargament, Cole, Rye, Butter, Belavich et al., 1997). For instance, while some religious behaviors (e.g., frequent religious practice, prayer, and church attendance) are correlated with some dimensions of spirituality, many aspects of spirituality are independent of self-reported religious behaviors (Heintz & Baruss, 2001).

The “will to meaning”–constructing meaning from life’s events–is an essential human characteristic, a critical element of psychological well-being (Fetzer Institute, 1999; Ryff 1989), and one that can lead to physical and mental discomfort if blocked or unfulfilled (Frankl, 1963). Antonovsky (1979) has noted the importance of meaning or purpose in life as part of a sense of coherence; meaning provides context that is essential to understand and successfully cope with life’s difficulties (Fife, 1994; Park & Folkman, 1997). Life meaning is an inherent part of the spiritual pursuit (e.g., Speck, 2004); it has received virtually no attention in the addiction field to date.

Scientific literature strongly supports the notion that spirituality and religiousness can enhance health and QOL. In a review of 200 + studies, positive relationships were documented with physical and functional status, reduced psychopathology, greater emotional well-being and improved coping (Matthews, Larson, & Barry, 1993; Matthews & Larson 1995). These studies show that religious/spiritual beliefs typically play a positive role in adjustment and in better health (Brady, Peterman, Fitchett, Mo, & Cella, 1999; for review, Koenig, MuCullough, & Larson, 2001). Spirituality was included in the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life instrument (WHOQOL) after focus group participants worldwide reported that spirituality was an important component of their QOL (The WHOQOL Group, 1995). Persons with strong religious faith report higher levels of life satisfaction, greater happiness, and fewer negative psychosocial consequences of traumatic life events (Ellison, 1991).

A large body of research has investigated the role of religiousness and spirituality in dealing with stressful situations. In that context, religious and spiritual beliefs and practices appear to function as protective factors or buffers that mediate or moderate the relationship between life stressors and quality of life (e.g., Culliford, 2002; Miller & Thoresen, 2003; for review, see Fetzer Institute, 1999). For example, Landis (1996) has reported findings suggesting that spirituality buffers uncertainty in the face of chronic illness. Reliance on spiritual beliefs and engaging in spiritual activities can give hope, strength, and provide meaning during stressful periods (e.g., Galanter, 1997); Underwood and Teresi (2002) use the expression ‘social support from the divine’ (p. 31). The extant literature has documented a strong and consistent inverse relationship between spiritual well-being (SWB–a multidimensional construct that incorporates both existential well-being or life meaning, and spiritual beliefs–Ellison, 1983) and negative affect among persons in stressful situations (e.g., Fehring, Brennan, & Keller, 1987). In one study among persons with chronic illnesses, the ‘non-spiritual’ group reported lower levels of QOL and life satisfaction than did the ‘existential’ and the ‘religious’ groups (Riley, Perna, Tate, Forchheimer, Anderson, & Luera, 1998); SWB has also been shown to contribute to QOL even after controlling for the influence of mood, emotional well-being and social desirability (Brady et al., 1999). Studies of persons with chronic and/or terminal illness (e.g., cancer, HIV disease) have reported positive associations between spiritual well-being and QOL (e.g., Cohen, Hassan, Lapointe, & Mount, 1996; Coleman, 2004; Cotton, Levine, Fitzpatrick, Dold, & Targ, 1999; Fry, 2001; Laudet et al., 2000; Levine & Targ, 2002; Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart, & Galietta, 2002; Volcan, Sousa, Mari Jde, & Horta, 2003). One study demonstrated significant associations between spiritual well-being and hardiness, as well as between existential well-being and hardiness among persons who were HIV positive or who had diagnoses of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related complex (ARC) or AIDS, supporting the notion that spirituality may confer resiliency in stressful situations (Carson & Green, 1992); hardiness is a personality trait that buffers stress toward positive outcomes in a variety of contexts (Kobassa, 1979). The few studies that sought to assess independently the role of religiousness and spiritual beliefs in moderating stress have reported findings suggesting that the beneficial aspects of religion on QOL may be primarily related to spiritual well-being and to life meaning rather than to religious practices per se (e.g., Cotton et al., 1999; Mickley, Soeken, & Belcher, 1992; Nelson Rosenfeld, Breitbart, & Galietta, 2002; Tsuang, Williams, Simpson, & Lyons, 2002).

In addition to enhancing QOL and to offering resiliency in stressful situations, spirituality and religiousness have also been studied in association with substance use behavior. A fairly large body of evidence shows an inverse relationship between involvement in religion (e.g., attending services, considering religious beliefs important) and likelihood of substance use across life stages (Benson, 1992; Johnson, 2001; Koenig et al., 2001; The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University, 1998, 1999; Stewart, 2001); most results from a large scale study using latent growth analysis showed that religiosity reduced the impact of (buffered) life stress on initial level of substance use and on rate of growth in substance use over time among adolescents (Wills, Yaeger, & Sandy, 2003). Possible protective mechanisms conferred by religious involvement may include avoidance of drugs, social support advocating abstinence or moderation, time-occupying activities that are incompatible with drug use, and the promotion of pro-social values by the religious affiliation that includes leading a drug-free life (Morjaria & Orford, 2002). The association between religiosity/spirituality and lower substance use, together with the growing interest in the role of spirituality and religious faith in QOL and in clinical care, have resulted in renewed interest in this topic in the addiction field: “if religious and spiritual involvement can act as a protective factor, it should come as no surprise that it could act as a means of ridding oneself of an addiction” (Morjaria & Orford, 2002, p. 226). Evidence for the growing interest in spirituality and religion among addiction professionals include the recent publication of white papers (e.g., The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University, 2001) as well as by a request for applications (RFA) entitled “Studying Spirituality and Alcohol,” sponsored jointly by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health and the John E. Fetzer Institute (RFA: AA-00-002, 2000). This is historically significant. Nearly seventy years ago, when the recovery program of Alcoholic Anonymous was first put forth in the Big Book, Bill W. wrote “for we have not only been mentally and physically ill, we have been spiritually sick. When the spiritual malady is overcome, we straighten out mentally and physically” (Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, 3rd edition, 1939/1976, p. 64). The suggested strategies to overcome the “spiritual malady” of alcoholism as put forth in the 12-steps that provide the spiritual foundation of the AA recovery program can be summarized thus: “The alcoholic at certain times has no effective defense against the first drink. (…) His defense must come from a Higher Power” (p. 43–see next section for discussion). Subsequently, as the professionalization and the medicalization of addiction treatment grew, the spiritual emphasis of the 12-step program came to be–and often remains–one of its more controversial and criticized aspects (e.g., Connors & Dermen, 1996; Davis & Jansen, 1998; Klaw & Humphreys, 2000).

Nonetheless, a growing body of empirical research supports the notion that religiousness and spirituality may enhance the likelihood of attaining and maintaining recovery from addictions, and recovering persons often report that religion and/or spirituality are critical factors in the recovery process (e.g., Christo & Franey, 1995; Green et al., 1998; Kus, 1995; Matthew & Saunders, 1997; Margolis et al., 2000; McDowell, Galanter, Goldfarb, & Lifshutz, 1996; Morjaria & Orford, 2002; Richard et al., 2000). Most studies in this area have been somewhat limited by methodological shortcomings (e.g., small sample). Recently, a growing number of large-scale, well-designed studies using quantitative methods have also documented the importance of spirituality to maintaining recovery (e.g., Flynn, Joe, Broome, Simpson, & Brown, 2003; Laudet et al., 2000) and a handful of long-term studies documented the association between increased involvement in religion and remission among alcoholic individuals (Vaillant & Milofsky, 1982; also see Moos & Finney, 1990). Moreover, there is evidence that spirituality increases from pre- to post-recovery (Mathew, Georgi, Wilson, & Mathew, 1996; Miller, 1998) and that among recovering individuals, higher levels of religious faith and spirituality are associated with cognitive processes previously linked to more positive health outcomes including more optimistic life orientation, higher resilience to stress, lower levels of anxiety, and positive effective coping skills (Pardini, Plante, Sherman, & Stump, 2000; Kondo, Iimuro, Iwai, Kurata, Kouda, Tachikawa, Nakashima, & Munakata, 2000). In sum, there is support for the positive role that spirituality and religiosity can play in minimizing substance use behavior, and preliminary evidence that this dimension may also facilitate the process of recovery from addictions.

AFFILIATION WITH 12-STEP FELLOWSHIPS

Twelve-step fellowships (e.g., Narcotics and Alcoholics Anonymous) are the most widely available addiction recovery resource in the US. Affiliation with 12-step fellowships, both during and after treatment, is a cost-effective and useful approach to promoting recovery from alcohol–and other drug-related problems (e.g., Christo & Franey, 1995; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000, Humphreys & Moos, 2001; McKay, Merikle, Mulvaney, Weiss, & Kopenhaver, 2001; Miller, Ninonuevo, Klamen, & Hoffmann., 1997; Montgomery, Miller, & Tonigan, 1995; Morgenstern, Labouvie, McCray, Kahler, & Frey, 1997; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997; Timko, Moos, Finney, & Lesar, 2000; for reviews: Tonigan, Toscova, & Miller, 1996; Humphreys, Wing, McCarty, Chappel, Gallant, Haberle et al., 2004). Although the bulk of 12-step studies have focused on substance use as the primary outcome, there is also some evidence that the benefits of 12-step affiliation extend to other areas of psychosocial functioning including less severe distress and psychiatric symptoms, higher likelihood of being employed, and enhanced quality of life (e.g., Gossop, Harris, Best, Man, Manning, Marshall, & Strang, 2003; Moos, Finney, Ouimette, & Suchinsky, 1999).

The 12-step program of recovery as formulated by its founders (AA, 1939/1976) uses a 3-pronged approach: unity (fellowship, traditions and principles of the program), service (chairing meetings, qualifying, setting up the meeting space), and recovery (“working” the 12-step program). The recovery program is a set of suggested strategies that are based on a spiritual foundation whereby the individual is encouraged to rely on an external power greater than him/herself (Higher Power that many choose to call God), although no religious affiliation or belief is a requirement for 12-step membership. In fact, the AA founders specifically address this issue in one of the early chapters of the Big Book1 (“We agnostics,” AA World services, 1939/1976) and the few empirical investigations of the association between religiosity and 12-step participation have found that extent of religious beliefs does not appear to affect the benefits derived from 12-step participation (Tonigan, Miller, & Schermer, 2002; Winzelberg & Humphreys, 1999).

Meeting attendance is the most popular and the most researched form of 12-step participation. Members attend meetings to share “their experiences, strength and hope” in an accepting environment; new members gain hope and coping strategies from more experienced “old-timers” and more experienced members come to “keep it green” (i.e., to remember their past experiences with drug use by listening to new members). Fellowship with other recovering persons is one of the cornerstones of 12-step recovery and is credited by recovering individuals as a critical source of support (e.g., Laudet et al., 2002; Margolis et al., 2000; Nealon-Woods, Ferrari, & Jason, 1995). Twelve-step affiliation requires more than attending meetings, however. The benefits of meeting attendance can be enhanced through other suggested affiliative practices (e.g., Montgomery et al., 1995) and associated with more stable abstinence (Caldwell & Cutter, 1998). These practices include having a sponsor, working the 12-steps, having a home group, reading recovery literature, being active before and after meetings (e.g., setting up chairs and making coffee), and having between-meeting contact with other 12-step members (Caldwell & Cutter, 1998). In the absence of engaging in these activities, meeting attendance is associated with high attrition and with the consequent loss of the potential benefits of affiliation (Walsh, Hingson, & Merrigan, 1991). There is also evidence that embracing 12-step ideology (e.g., commitment to abstinence, reliance on a Higher Power, needing to work the 12-step program) predicts subsequent abstinence independently of meeting attendance (e.g., Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000). The benefits of working the 12-step program are likely to be at least partially independent of meeting attendance, and available in the absence of attendance, especially when recovery has stabilized and a program of recovery has been largely internalized. This does not imply that meeting attendance is not critical to the recovery process, especially early on; rather, it may be that over time, recovery becomes less dependent upon meeting attendance among persons who have come to embrace the program and strive to incorporate its principles in their life. One of a handful of long-term studies found that the most stable abstinence from alcohol over 10 years came from being a sponsor (Cross, Morgan, Moony, Martin, & Rafter, 1990) and working the steps has been shown to stabilize abstinence (Chappel, 1993; Vaillant, 1995). Large-scale prospective studies using long-term follow-ups are critically needed. Overall, 12-step affiliation is a multifaceted process, combining cognitive, behavioral, social and spiritual components. It provides exposure to similar status persons (peers) as well as to the organization’s ideology about these persons and their problems (Katz, 1993). This exposure is believed to lead to certain social and cognitive changes among members that, in time affect their behavior and well-being (Kingree & Thompson, 2000a and 2000b).

STUDY OBJECTIVES

The main objectives of this study are to examine stress and life satisfaction as a function of length of recovery, and to assess the role of a number of protective factors as “recovery capital” that may buffer stress and enhance life satisfaction among recovering persons. Specifically, we address two research questions: (1) Does quality of life improve over time?; and (2) Do factors previously identified as buffering stress and promoting stable recovery contribute to enhancing QOL among recovering persons? Using structural equation modeling (SEM), we test a model where social supports, spirituality, life meaning, religious practices, and affiliation with 12-step fellowships are hypothesized to buffer stress and to enhance quality of life satisfaction.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

This study was conducted in the context of a NIDA-funded prospective investigation of factors associated with stable abstinence from illicit drugs over time.

Sample

Recruiting was conducted in New York City through media advertisements placed in free newspapers (e.g., the Village Voice) and flyers posted throughout the community (e.g., libraries, coffee shops, and YMCAs). Recruiting was conducted over a one-year period starting in March 2003. The study maintained a toll-free telephone number that interested persons were directed to call. Callers were screened briefly (10–12 minutes). Information was collected on basic demographics, past and current drug use, lifetime dependence severity (using the Drug Abuse Screening Test–DAST 10–Skinner, 1982), current utilization of treatment services and contact information. Eligibility criteria for the study were: (1) fulfilling for a year or longer the DSM-IVR criteria for substance abuse or dependence of any illicit drug, (2) self-reported abstinence for at least one month, and (3) not being enrolled in residential treatment.2 Eligible callers were contacted within a week to schedule an in-person interview. Seven hundred and two unduplicated screeners were conducted; of those, 440 were eligible; 353 were interviewed (82% of eligibles). [Reasons why 87 eligibles were not interviewed: unable to contact with information given at screener–e.g., disconnected telephone (39), did not come to appointment and unable to contact to reschedule (22), refused (10), relapsed between screening and scheduling call (6), data collection ended (10).]

The interview session started by explaining the voluntary nature of the study, what participation in the study entails; the signed informed consent procedure was then administered and the interview was conducted, lasting two and a half hours on average. Participants were paid $30 for their time. The study was reviewed and approved by the NDRI Institutional Review Board (IRB) and we obtained a certificate of confidentiality from our funding agency. The analyses presented here were conducted on the baseline cohort of 353 participants.

Measures

The study used a semi-structured instrument; in addition to socio-demographics and background, we used the measures described below. Unless otherwise stated, higher scores represent a higher level of the construct under study; Chronbach Alpha reliability scores reported are those obtained for this dataset.

Dependence severity

We used the Lifetime Non-alcohol Psychoactive Substance Use Disorders subscale of the The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.), a short structured diagnostic interview developed in the United States and Europe for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders (Sheehan, Lecrubier, Harnett-Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller et al., 1998). The MINI has become the structured psychiatric interview of choice for psychiatric evaluation and outcome tracking in clinical psychopharmacology trials and epidemiological studies. The M.I.N.I. has been validated against the much longer Structured Clinical Interview for DSM diagnoses (SCID-P) in English and French and against the Composite International Diagnostic Interview for ICD-10 (CIDI) in English, French and Arabic. The 14 items answered in a yes/no format yield a single score ranging from 0 to 14. Sample item: “When you were using [primary substance], did you ever find that you needed to use more [primary substance] to get the same effect that you did when you first started taking it?” Cronbach’s Alpha = .81.

Clean time

Drug and alcohol use history was collected using a list of 13 substances based on the ASI (McLellan, Kushner, Metzger et al., 1992). For each substance ‘ever’ used once or more, participants provided the last date of use; a variable was computed for clean time from each substance ever used; the clean time variable used in the analyses represents time since most recent use of any of the illicit drug ever used, in months (i.e., if participant last used heroin 4 years ago and crack 5 months ago, clean time for the present analyses is 5 months).

Stress

“Overall, how stressed have you been in the past year?” Answer scale: 0 = not at all to 10 = extremely.

Stressful life events

We used an 11-item inventory developed by the first author; participants indicate whether they have experienced each event in the past year; sample items: “personal injury or illness,” “Increased responsibility (e.g., financial, home, work)” and “death of a loved one.” The analyses use a sum score so that a higher score reflects a greater number of stressful events in the past year.

Recovery support

The Social Support for Recovery Scale (SSRS) consists of 11 items rated on a Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree); sample item: “The people in my life understand that I am working on myself” (Laudet et al., 2000). Negatively phrased items are reversed and the score used here is the sum of the 11 items. Cronbach’s Alpha = .88.

Social support

The 23-item Social Support Appraisal Scale (SSA; Vaux & Harrison, 1985; Vaux, 1988) measures the degree to which a person feels cared for, respected, and involved with friends, family and other people. Items are rated on a Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Sample item: “My friends respect me,” “I don’t feel close to members of my family.” Cronbach’s Alpha = .92.

Spirituality, life meaning and religious practices

(1) The Spirituality subscale of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS–Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982) consists of 6 items rated on a Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree) and yields one score representing “the affirmation of life in relationship with God, self, community and environment” (Ellison, 1983, p. 331). We adapted the wording of the items to a broader dimension of spirituality (from “God” to “God/Higher Power”). Sample items: “I don’t get much personal strength and support from God/my Higher Power” and “I have a personally meaningful relationship with God/my Higher Power.” Cronbach Alpha = . 82. (2) Life meaning was assessed using the Existential Subscale of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982), consisting of 6 items rated as described above; it yields a score (after reversing the three that are negatively phrased) representing one’s perception of life’s purpose, apart from any religious reference. Sample items: “Life doesn’t have much meaning,” and “I believe there is some real purpose for my life.” Alpha = .87. (3) We used the Religious Background and Behavior (RBB) questionnaire to assess religious activities in the past year (Connors, Tonigan, & Miller, 1996). The instrument measures frequency of (a) thinking about God; (b) prayer or meditation; (c) attending worship services; (d) reading/studying scriptures or holy writings; and (e) having a direct experience with God; answer categories range from never to once a day. Cronbach’s Alpha = .81.

Twelve-step affiliation

Affiliation consists of two dimensions: meeting attendance and involvement in 12-step suggested activities. (a) Meeting attendance is the number of 12-step addiction recovery meetings attended in the past year (AA, NA or CA); (b) 12-step involvement is the sum of nine 12-step activities in the past year: having a sponsor; sponsoring someone; considering oneself a member of AA, NA or CA; having a home group; working the steps; doing service; having contact with 12-step fellowship members outside of meetings; reading 12-step or recovery literature outside of meetings; and socializing with 12-step members outside of meetings.

Quality of life satisfaction

The main dependent variable in the analyses was measured with the following item: “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life right now?” answered on a visual scale where 1 = “not at all,” and 10 “completely.” We used this measure because we were interested in assessing participants’ overall evaluation of their life satisfaction, taking into account the balance between positive and negative as it was relevant to their individual experience.

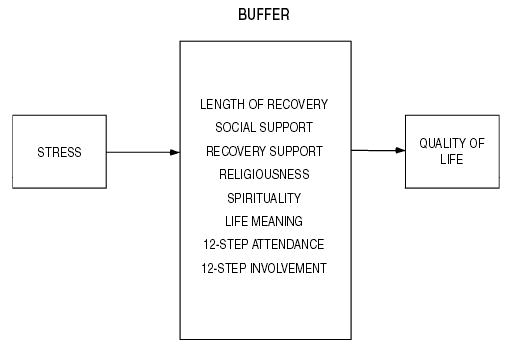

Analytic Plan

The analyses were conducted in several stages. First, descriptive statistics examine the key variables under study, and bivariate associations among these variables are examined. Next, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test a model assessing the collective effect of length of time in recovery time, social support, recovery support, spirituality, life meaning, religious practices, and 12-step affiliation as hypothesized mediators of stress on quality of life. A simple graphic representation of our hypothesized model, developed from the literature reviewed above, is presented in Figure 1. Finally, a simple linear regression was conducted to assess the magnitude of the influence of each individual observed variable hypothesized to influence quality of life satisfaction, since SEM results bear on the simultaneous influence of all variables in the latent variable but not on the strength of their individual influence.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized model: Supports, spirituality/religiousness and 12-step affiliation that buffer quality of life satisfaction from stress.

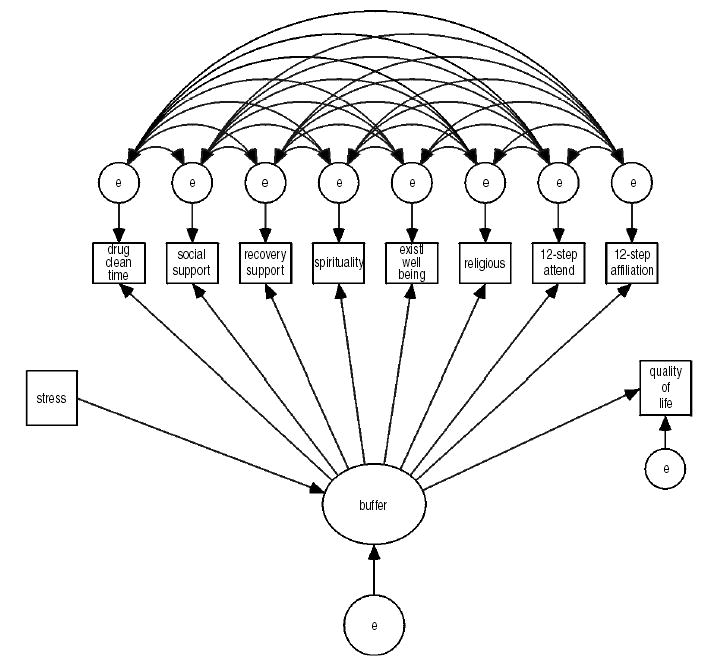

The structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses tested the appropriateness of the model in Figure 1 using maximum-likelihood estimation within AMOS 4.0 (Arbuckle, 1999). SEM analyses examine observed and unobserved (or latent) constructs to ascertain a relationship among all variables. Observed variables, represented as boxes in the SEM figures discussed in the Results section (Figures 2 and 3), are measurable (e.g., a scale score). Unobserved or latent variables are represented by an oval in the SEM figures.

FIGURE 2.

Original hypothesized SEM with all error terms covarying.

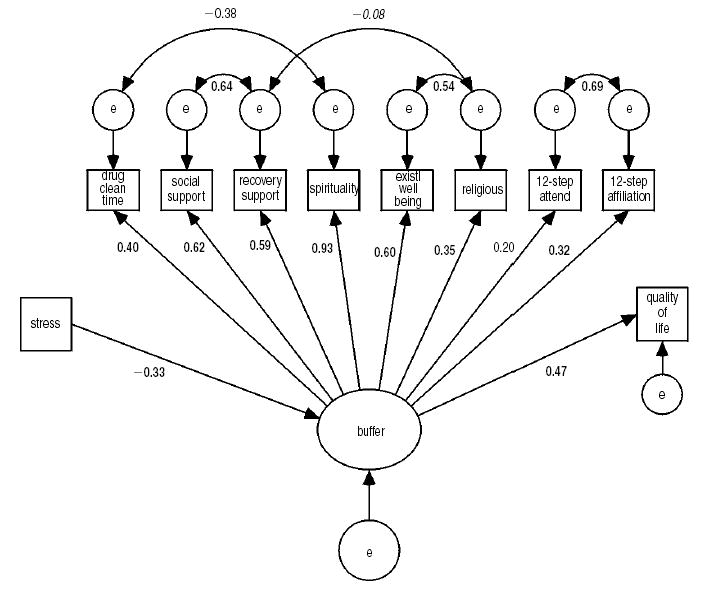

FIGURE 3.

Final structural equation model.

In this study, we tested the hypothesized model whereby recovery time, general social support, recovery support, spirituality, life meaning, religious practices, and 12-step affiliation constitute a buffer that mediates the relationship between life stress and overall quality of life satisfaction. Figure 2 reflects the tested model and shows paths that were modeled from the observed general measure of perceived stress in the past year to the latent variable buffer. Another path was then modeled from the latent variable to the observed quality of life measurement. This represents a full Structural Equation Model as it reflects both a path analysis (stress → buffer → quality of life) and a confirmatory factor analysis (the eight observed measurements that explain the latent variable). Adequacy of model fit was assessed with standardized coefficients obtained from the maximum likelihood method of estimation. To determine model fit, we used the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index, the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio, and the root mean square of approximation (RMSEA). Once modeled, the significance of path coefficients, variances, and covariances is determined by examining the critical ratio (CR). Any CR > 1.96 is significant at the .05 level and indicates that path coefficient or covariance has a significant effect on the model. In addition, the R-squared (or squared multiple correlation) shows the percent of variance explained by the model for that particular endogenous (dependent) variable (Byrne, 2001). Although model fit indices and significance of path coefficients and covariances assist in model evaluation, the final determination of the “best” model tends to be a subjective and theoretical judgment.

RESULTS

Descriptives

Sample

The sample was 56% male; 62% African-American, 16% non-Hispanic white, and 22% of other or mixed ethnic/racial background; 19% were of Hispanic origin. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 65 years (mean = 43, Std. Dev. = 8). Educational attainment ranged from 5 to 19 years of schooling (mean = 12 year, Std. Dev. = 2). Nineteen percent were employed part-time, 21% full time; 60% cited government or other benefits (e.g., Veteran’s pension) as primary source of income. Over half (56%) were single, 16% were married and 28% were widowed, separated or divorced. Nearly one quarter (22%) reported being seropositive for HIV antibodies. The majority (82%) had no current involvement with the criminal justice system; 18% were on probation or parole. The majority of participants were polysubstance users; lifetime dependence severity was high. Most frequent primary problem substance was crack followed by heroin (18.5%). Clean time ranged from one months to ten years. Means and standard deviations for key variables under study are displayed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Key Variables Descriptives (N = 353)

| Possible Range | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clean time from drugs (in months) | 1–120 | 26.5 | 31.5 |

| Dependence severity | 0–14 | 11.7 | 2.4 |

| Stress | 0–10 | 6.3 | 2.6 |

| Stressful Life events | 0–11 | 3.9 | 2.1 |

| Recovery Support | 1–4 | 3.0 | .30 |

| Social Support | 1–4 | 3.0 | .35 |

| Spirituality | 0–4 | 3.0 | .39 |

| Religious activities | 0–8 | 5.1 | 1.7 |

| Life Meaning | 1–4 | 3.2 | 5.1 |

| Twelve-step affiliation: | |||

| Ever Narcotics Anonymous (NA) | ---- | 87% | |

| Ever Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) | ---- | 72% | |

| Past year Narcotics Anonymous | ---- | 69% | |

| Past year Alcoholics Anonymous | ---- | 47% | |

| Any 12-step attendance past year (NA or AA) | ---- | 73% | |

| Total (NA+AA) meetings past year* | ---- | 141 | 135 |

| 12-step involvement (activities in NA+AA)* | 0–9 | 4.2 | 3.5 |

| Quality of life satisfaction | 0–10 | 7.5 | 1.9 |

among past year attenders

On average, stress level and number of stressful life events in the past year were moderate; life satisfaction was high, as were levels of both recovery-specific support and general social support, as well as life meaning (existential well-being) and spirituality. Religious activities were more moderate.3 Nearly three-quarter of participants had attended a 12-step meeting in the past year; involvement in 12-step activities was more moderate.

Bivariate associations among key variables

First we examined whether there were significant differences in either stress level or in quality of life between men and women, between individuals who reported being HIV seropositive and seronegative, and as a function of age. No differences emerged for quality of life. Stress was significantly and negatively correlated with age (older age, less stress. r =−.14, p = .01) but the association lost statistical significance when recovery time was held constant (partial correlation, r = −.07, p = .20). This is not unexpected as older individuals are more likely to have been in recovery longer.

Next we examined the bivariate associations among key variables. Zero-order two-tailed Pearson R coefficients are reported in Table 2. Longer duration of clean time was significantly associated with lower levels of stress (overall stress rating and fewer stressful events in the past year), greater levels of social (but not recovery) support, greater spirituality, more religious activities, greater meaning in life and greater quality of life. Dependence severity was not significantly associated with either stress levels or quality of life. Higher stress levels were significantly associated with lower recovery and social supports, with lower spirituality levels, fewer religious activities, less 12-step meeting attendance and involvement, and lower quality of life satisfaction. Finally, in addition to longer recovery time and lower stress, significant correlates of quality of life were: greater levels of recovery an social support, higher spirituality ratings, greater involvement in religious activities, grater level of life meaning and, greater 12-step involvement (but not attendance).

TABLE 2.

Bivariate Associations Among Key Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Clean time from drugs (in months) | 1 | .01 | −.27** | −.20** | .08 | .14** | .14* | .13* | .11* | .09 | .06 | .21** |

| 2. Dependence severity | 1 | .09 | .10 | −.03 | −.11* | −.03 | .16** | .13* | .13 | .27** | −.04 | |

| 3. Stress | 1 | .30 | −.18** | −.22** | −.27** | −.11* | −.10 | −.14* | −.12* | −.29** | ||

| 4. Stressful Life events | 1 | −.07 | −.08 | −.04 | .04 | .09 | .15* | .00 | −.09 | |||

| 5. Recovery Support | 1 | .77** | .56** | .11* | .31** | .23** | .26** | .31** | ||||

| 6. Social Support | 1 | .58** | .18** | .38** | .19** | .19** | .33** | |||||

| 7. Spirituality | 1 | .35** | .58** | .20** | .26** | .44** | ||||||

| 8. Religious activities | 1 | .67** | .13 | .32** | .33** | |||||||

| 9. Life Meaning | 1 | .19** | .26** | .28** | ||||||||

| 10. Total (NA+AA) meetings past year | 1 | .54** | .07 | |||||||||

| 11. 12-step involvement | 1 | .22** | ||||||||||

| 12. Quality of life satisfaction | 1 |

p < .05.

p < .01; all correlations are two-tailed

Structural Equation Modeling4

Data were examined for normality prior to testing the model. With exception of the 12-step involvement and recovery support, all study variables were significantly skewed. Transformations were performed to bring the values closer to a normal distribution. Logarithmic transformations were performed on positively skewed variables and the quadratic transformation was performed on negatively skewed variables, using the In SPSS 11.5 software.5

Initial model

The first model (Figure 2) estimated all error terms as co-varying with one another and produced a good fit to the data. The χ2/df = 1.49, CFI = 1.000, Tucker-Lewis = .997, RMSEA = .037 (95% CI: 0 to .081). All the observed loadings on the latent variable were significant (p < .001), thus the latent variable appears adequately measured by the indicators. The two paths leading into and out of the latent variable were also significant. However, less than one-third of the co-variances were significant. Although a discrepancy between the good fit indices and many insignificant co-variances appears, the good fit of the model may have been due to this model being overly fitted with 58 parameters and only 7 degrees of freedom (see Kline, 1998). Therefore, we tested a revised model with only the significant co-variances remaining.

Final model

Though not fitting as well as the original model, the revised (final) model adequately fit the data (Figure 3). The χ2/df = 3.58, CFI = .99, Tucker-Lewis = .985, RMSEA = .086 (95% CI: .068 to .103). Again, all latent variable and path loadings were significant. In addition, the remaining error co-variances were significant. The error co-variances refer to situations in which knowing the residual of one indicator helps in knowing the residual associated with another indicator. Knowing that a respondent gave a certain response to one item increases the probability that a similar response will be given to another item. Such an example exhibits correlated error terms. Uncorrelated error terms are an assumption of regression, whereas the correlation of error terms may and should be explicitly modeled in SEM. That is, in regression the researcher models variables, whereas in SEM the researcher must model error as well as the variables.

We found significant positive relationships between the error terms of recovery support and social support (p < .001), the number of 12-step meetings attended in the past year and the degree of active involvement in the 12-step program (p < .001), religious involvement and existential well-being (p < .001), while finding significant negative relationships between time abstinent from drug use and spiritual well-being (p < .01), and between religious involvement and recovery support (p < .05).

The squared multiple correlation (SMC) is independent of measurement units and represents the proportion of variable variance explained by the predictors of that variable. The analyzed model was designed to explain the influence of variables under study on quality of life, and results from the final model showed that 22.2% of the variance associated with quality of life is accounted for by its predictors in the model.

We also tested the significance of the indirect effect of stress on quality of life, as mediated through the latent variable buffer. Using the Sobel Test (see Baron & Kenny, 1986; Shrout & Bolger, 2002; Sobel, 1982), we found a significant indirect effect of stress of quality of life (critical ratio = −3.20, p < .001), indicating that as stress is reduced via interaction with the latent variable buffer, quality of life increases.

Findings from the linear regression analysis examining the individual contribution of each of the eight variables assessed in combination as ‘buffer’ in the SEM analyses reported above were significant (p < .001) for all variables except 12-step attendance: length of clean time for length of clean time (0.302), social support (0.310), recovery support (0.270), spirituality (0.412), existential well-being (.237), religiousness (0.292), and 12-step affiliation (0.186). The percentage of variance explained by each individual variable ranged from 0 to 17%; taken together, the individual contribution of these eight variables accounted for 60.6% of the variance in quality of life satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that the hope for “a better life” that motivates alcohol and drug users to initiate the recovery process may become a reality for many; moreover, findings supported our hypothesis that social supports, spirituality, life meaning, religiousness and 12-step affiliation buffer stress significantly and enhance quality of life among recovering persons. First, overall stress levels were moderate and QOL was relatively high in this sample of inner-city former polysubstance users, most of whom were members of ethnic/racial minority groups. Moreover, findings suggest that stress levels decrease significantly as time in recovery increases, and that life satisfaction increases over time. This study is among the first to address this important research questions and to do using a relatively large, diverse sample of polysubstance drug users; our findings are consistent with previous study and extend their generalizability (e.g., Weaver et al., 2000; Foster et al., 2000).

Second, levels of factors previously identified as enhancing QOL and recovery were also generally high. This was particularly true of general social support and recovery support, spirituality, life meaning, and 12-step attendance. In addition, a number of these protective factors were significantly and positively correlated with recovery time, suggesting that levels increases over time: in particular, social support, spirituality, religious activities and life meaning. Recovery-specific support did not increase; this may be because over time, recovering persons become less focused on abstinence and concentrate more on “living a normal life” where recovery-specific support may be less critical than is general social support; that transition occurs after a more intense abstinence-focused period lasting from one to two-years (Margolis et al., 2000); we note that over one half (56%) of our sample was in recovery for longer than one year; further, examination of recovery support over the course of length of recovery traced an inverted U-shaped curve, starting relatively low, increasing to a peak at between one and two years of recovery, and slopping down gradually to more moderate levels.

Twelve-step attendance and involvement did not increase over time; few studies have examined 12-step affiliation over the course of recovery so that little is known about this important topic. Here, the finding was unexpected because we have reported elsewhere that in this sample, among those who reported lifetime 12-step participation (‘ever’), NA attendance increased over the course of recovery while AA participation decreased (Laudet & White, 2004). Thus, we believe that the finding that 12-step affiliation did not correlate significantly with length of recovery may be due to a measurement artifact in the present study where attendance and involvement in Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous were combined, a decision we made based on the study aims to examine the role of 12-step affiliation overall, on QOL. Zemore and Kaskutas (2004) recently reported that among recovering alcoholics, levels of AA involvement (attendance and activities–e.g., reading recovery literature) were not associated with length of sobriety, but that what the authors termed “AA achievement” (“the degree to which respondents had worked the program,” p. 385) was significantly and positively associated with length of sobriety. Future research is needed that examines separately NA and AA affiliation among recovering poly-substance users; we plan such analyses using longitudinal data in the future.

Present findings also suggest that spirituality, religious practices and life meaning increase moderately as recovery progresses. A handful of previous reports have indicated that spirituality increases from pre- to post-recovery (e.g., Mathew et al., 1996; Miller, 1998). Substance users often come into recovery feeling abandoned by God or alienated from God or from the religious community, as expressed by a research participant cited by The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (2001):

Being in recovery has changed the way I see God. I came into recovery with a God, but it was a punishing, vengeful and unforgiving God. I had done so many things … I knew were ungodly, that I thought for sure I was going to Hell. … When I came into recovery I found a new God. I found a God that was loving, forgiving, understanding and responsive to the need that I have. In retrospect, I can see that God has been with me all the time. Craig, Age 44, African American Male (p. 41)

Spirituality, religiousness and life meaning enhance coping, confer hope for the future, provide a heightened sense of control, security and stability; they confer support and strength to resist the opportunity to use substances, all of which are very much needed to initiate and maintain recovery (for reviews, see Cook, 2004; The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2001; The Fetzer Institute, 1999). While not all recovering persons embrace spirituality/religiousness, many report that a spiritual or religious connection to the transcendent is part of their recovery. Recovering participants in one study expressed a sense of needing something to depend on that could be trusted and that was there always (Morjaria & Orford, 2002). Recovering person also express often that lack of a spiritual or religious connection contributed to the escalation of their problem (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2001). Of note, previous religiousness or spirituality is not a prerequisite to gaining the benefit of spirituality in recovery (e.g., Christo & Franey, 1995; Jones, 1994), suggesting that this critical recovery resource may be available to all who seek it (see later discussion).

Third, findings supported the hypothesized role of social supports, spirituality/religiousness, life meaning and 12-step affiliation in buffering stress and in enhancing quality of life in this recovering sample. Granfield and Cloud’s (1999) concept of recovery capital may help interpret this finding. Recovery capital is the amount and quality of internal and external resources that one can bring to bear to initiate and sustain recovery from addiction. Social supports and 12-step affiliation are among key external resources previously associated with stable recovery; spirituality and faith, as well as the benefits they confer–hope, a sense of control and security, and emotional support–constitute internal resources that have been linked to positive health outcomes. This study extends current knowledge about the benefits of these resources to QOL in the recovering community. This is important for several reasons. First, little is known about the recovery experience beyond the short post-treatment period that is typical of most addiction research designs. Recovery is a lifelong, dynamic process and it is therefore critical to learn more about relevant challenges and helpful resources (recovery capital) over the course of the process in order to enhance the likelihood that stable recovery be maintained. Second, most studies in the addiction field focus on substance use as the primary outcome. Recovery goes well beyond substance use; in particular, quality of life is a critical domain in behavioral health research that has been neglected thus far by addiction researchers. As Stanton Peele wrote, addicts improve when their relationships to work, family, and other aspects of their environment improve (1985); that is to say, quality of life is critical to the recovery process and it is critical that we identify factors that influence (enhance and/or threaten) QOL among recovering persons. Third, substance use begins and continues in the broader psychosocial context of the user (including one’s social network, beliefs, and social environment–see Moos, 2003). Therefore, recovery must be studied in that context as well, lest we obtain only a fragmented picture of a complex and dynamic process. In the same way as an individual’s existential beliefs, community participation, socioeconomic factors and peer network (to name only a few) influence substance use behavior, these factors play a key role in the initiation and maintenance of personal change (recovery). The concept of recovery capital opens up the possibility of broadening an understanding of recovery through a greater appreciation of a person and his/her embeddedness within social and cultural life (Granfield & Cloud, 2001).

This study has a number of limitations that must be considered when interpreting findings, chief of which are the non-random sample and the cross-sectional design. As a result of the latter, our findings cannot speak to causation or to the mechanisms underlying the stress buffering effect of the domains under study. Fieldwork on the first of three yearly waves of follow-up data collection began in the spring of 2004; the questions addressed here will be re-examined using a longitudinal design. With respect to sample representativeness, the scarcity of information on the recovering community makes it extremely difficult to determine how representative the present sample is from the recovering population as a whole. This study was conducted in New York City and recruited primarily inner-city, ethnic/racial minority members whose primary substances were crack and heroin. The associations investigated here should be examined again among diverse samples of participants to determine whether present findings are generalizable. Finally, using single items to assess stress and quality of life may be viewed as a limitation; we selected these measurements because we were interested in participants’ overall subjective assessment of stress and life satisfaction. Present findings are consistent with prior reports on both stress and QOL that used a variety of measures ranging from single items to sophisticated scales, suggesting that this measurement limitation may not significantly compromise the interpretation of results presented here.

This study also has a number of strengths and implications for both researchers and for clinicians. We used a relatively large sample of mostly inner-city members of minority groups who are under-represented in behavioral health research. The quantitative approach and the use of sophisticated statistical techniques applied to the study of recovery, spirituality/religion, and QOL contribute to current knowledge that, for the most part, has been obtained from small-scale qualitative studies. Further, empirical studies to date have generally not recognized the distinctions between spirituality and religions but instead have treated them as the same general concept, often using a single item (Connors, Tonigan, & Miller, 1996; Cook, 2004; Miller & Thoresen 2003; Speck, 2004); we assessed separately spirituality, religiosity and life meaning. Although the history of alcohol and other drug use is intertwined with spirituality and religion, there has been relatively little attention among researchers on the incorporation of spirituality in the treatment of addictions (Miller, 1998, 1999) or in studying their role in the process of recovery (Morjaria & Osford, 2002).

This study represents but a first step in a much-needed investigative effort that would focus on the role of spirituality and faith as recovery capital. As recently noted in the white paper So Help me God: Substance Abuse, Religion and Spirituality, by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, more research is needed to document pathways through which religion and spirituality work to prevent substance abuse and aid in recovery (2001). Previously, Finney (1995) has argued for the need to identify the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of factors associated with positive health outcomes. We plan on examining the research questions addressed here and to investigate the underpinning of the association between spirituality/religion and quality of life using longitudinal data. We also hope that the present study will stimulate research interest in this critical yet under-investigated area.

Additional implications for research include: (1) The importance of extending the investigative scope of studies on addiction and particularly, on recovery, beyond substance use; QOL is a critical yet under-investigated domain in the addiction field thus far. Here, the hypothesized buffers accounted for only 22% of the explained variance in QOL, suggesting that other factors are at play that were not measured in this study. (2) The need to incorporate spirituality and religiousness measures in the study of addiction and recovery, and to assess these constructs separately. (3) The importance of using statistical models that assess simultaneously, multiple domains of participants’ experience or recovery capital when seeking to identify factors contributing to the recovery experience. Here, each hypothesized protective domain accounts for a relatively small amount of the variance in QOL (regression results). Examining these factors simultaneously as recovery capital has greater explanatory power; it also lends greater external validity to the analyses by modeling statistically the real-life recovery experience as a dynamic process where a multiplicity of influences come to bear simultaneously on the individual.

Clinical Implications

Findings also have a number of implications for clinicians and for the recovering community. First, the finding that quality of life increases and that stress decreases as recovery progresses can give hope for a better future to individuals in early recovery who are struggling to stay drug-free and to move forward, often doing so “one day at a time.” Second, findings emphasize the importance of the recovery capital ingredients examined here (social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning and 12-step affiliation) in minimizing the stress attendant to the recovery process, and in enhancing life satisfaction. While necessarily focusing on substance use, clinicians should also take into account individual clients’ life situation, satisfaction levels and goals for the future, as well as clients’ social context and available recovery capital; this includes identify deficits in available recovery resources, and working with the individual to suggests supportive recovery resources that fit the person’s situation, needs, and beliefs (for discussion, see Granfield & Cloud, 2001; Moos, 2003; White & Sanders, 2004).

As discussed earlier, there is already overwhelming empirical evidence that 12-step affiliation is beneficial to the recovery process; present findings suggest that these benefits extend to the critical and most general domain of life satisfaction. The importance of general social support and domain-specific support (recovery support) in buffering stress and enhancing QOL emphasizes the need for recovering persons to establish a social network of persons who can provide encouragement, acceptance, and a sense of belonging. In that regard, affiliation with 12-step fellowships has been shown to minimize or eliminate the erosion of friendship networks that often attends the cessation of substance use (e.g., Ribisl, 1997; Humphreys, Mankowski, Moos, & Finney, 1999). However, many recovering persons drop out of 12-step fellowships relatively early on, and some never attend (e.g., Caldwell & Cutter, 1998; Fiorentine, 1999; Klaw & Humphreys, 2000; McCrady, Epstein, & Hirsch, 1996; McIntire, 2000; Morgenstern et al., 1996), so clinicians should not stop at encouraging 12-step affiliation as a source of recovery support. Rather, clinicians should work in partnership with clients on a case-by-case basis to develop strategies that maximize recovery capital (and its utilization) tailored to the individual’s situation; these strategies should be revisited periodically since needs and available resources make change as recovery progresses (for more substantial discussion of recovery management, we refer readers to McLellan, Lewis, O’Brien, & Kleber, 2000; White, Boyle, & Loveland, 2002, 2003; Dennis, Scott, & Funk, 2003). Participation in religious/spiritual congregations can also provide a supportive network (Berkman & Syme, 1979; House et al., 1988; for review, see Fetzer Institute, 1999). Again, as with 12-step fellowships, however, religious/spiritual group membership, while potentially beneficial for some, may not appeal to others. Thus, one of the most promising and potentially useful implication of our findings for clinicians centers on the beneficial role of spirituality and life meaning as a critical ingredient of recovery capital; these resources tend to be underutilized by clinical service providers (e.g., Miller, 1998). There is overwhelming evidence that persons receiving mental health services, including addiction services, view spirituality as essential to recovery, and a number of researchers have emphasized the need for clinicians to give more attention to clients’ spiritual needs (e.g., Arnold, Avants, Margolin, & Marcotte, 2002; McDowell, Galanter, Goldfarb, & Lifshutz, 1996; National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 2001). As noted by Arnold and colleagues (2002), interventions that attempt to address spiritual needs must be flexible enough to allow for several interpretations of spirituality, including conceptualizations of spirituality that do not include belief in a “higher power”; that is, the individual should be able to define spirituality for him/herself; this recommendation is consistent with the initial suggestion of Bill W. as set forth in the Big Book and discussed briefly earlier. Perhaps most promising and vastly neglected up to now is the importance of life meaning in the recovery process. Life meaning helps transcend the here and now, re-establish hope and the ability to cope (Speck 2004); this is particularly important for recovering individuals who may face painful and difficult realizations about the destructive consequences of their past use on their life and that of their loved ones, in addition to the difficulties they are encountering in the present. Life meaning does not need to be tied to specific sets of religious or spiritual beliefs, so that the pursuit of meaning as defined by the individual should be encouraged and fostered as part of rehabilitative and recovery services.

Overall, present findings suggest that the hope for a better life that sets many substance users on the path to recovery can be a reality; there is light at the end of the dark tunnel of active addiction for those who choose to change course and ‘to go to any length’ to seek recovery. That pursuit is stressful, challenging, lengthy, and requires a capital of recovery resources. With the ultimate goal of enhancing overall life satisfaction, present findings indicate that social supports, 12-step affiliation, spirituality, religiousness and life meaning have the potential of contributing to the overall recovery experience and thus, should be made an integral part of the menu of resources offered to the recovering community.

Footnotes

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the members of the recovering community who shared their experiences, strength and hope with our staff for this project.

“Much to our relief, we discovered that we did not need to consider another’s conception of God. Our own conception, however inadequate, was sufficient to make the approach and to effect a contact with Him. (…) To us, the Realm of Spirit is broad, roomy, all-inclusive; never exclusive or forbidding to those who honestly seek. It is open, we believe, to all men” (3rd edition, p. 46).

This is because the study is a naturalistic investigation of the role of psychosocial factors on long-term recovery, and we wanted to be able to assess the role of baseline community-related factors on subsequent outcome.

With respect to individual religious activities, 85% of participants reported thinking about God ‘daily’ or ‘almost daily,’ 78% prayed or mediated ‘daily’ or ‘almost daily,’ 33% attended worship services weekly or more often, 37% read or studied scriptures or holy writings at least weekly and 43% had a direct experience with God ‘daily’ or ‘almost daily’ whereas 29% never did and 20% rarely did.

Readers interested in more detailed statistical information pertaining to the analyses summarized here should contact the second author, Keith Morgen, at morgen@ndri.org

In the case of the stressful events variables, there were 24 individuals in the dataset who had reported no stressful event in the past year; these cases were considered statistical outliers from the remaining sample and were dropped from the analysis.

This work was supported by NIDA Grant R01 DA14409 and by a grant from the Peter McManus Charitable Trust to the first author.

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “The Role of Social Supports, Spirituality, Religiousness, Life Meaning and Affiliation with 12-Step Fellowships in Quality of Life Satisfaction Among Individuals in Recovery from Alcohol and Drug Problems.” Laudet, Alexandre B., Keith Morgen, and William L. White. Co-published simultaneously in Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly (The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 24, No. 1/2, 2006, pp. 33–73; and: Spirituality and Religiousness and Alcohol/Other Drug Problems: Treatment and Recovery Perspectives (ed: Brent B. Benda, and Thomas F. McGovern) The Haworth Press, Inc., 2006, pp. 33–73. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-HAWORTH, 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address: docdelivery@haworthpress.com].

Contributor Information

Alexandre B. Laudet, Alexandre B. Laudet is Director, Center for the Study of Addictions and Recovery (C-STAR), National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. (NDRI), 71 West 23rd Street, 8th floor, NY, NY 10010 (E-mail: laudet@ndri.org)..

Keith Morgen, Keith Morgen is Senior Research Associate, C-STAR at NDRI (E-mail: morgen@ndri.org)..

William L. White, William L. White is Senior Research Consultant, Chestnut Health Systems/Lighthouse Institute, 720 West Chestnut Street, Bloomington, IL 61701 (E-mail: bwhite@chestnut.org)..

References

- Alcoholics Anonymous World Services (1939/1976). Alcoholics Anonymous: The story of how many thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism 3rd Ed. NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services Inc.

- Alemi F, Stephens R, Llorens S, Schaefer D, Nemes S, Arendt R. The Orientation of Social Support measure. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1285–1298. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress, and coping San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Arbuckle, J. (1999). AMOS 4.0 [computer software]. Chicago: SmallWaters.

- Arnold R, Avants S, Margolin A, Marcotte D. Patient attitudes concerning the inclusion of spirituality in addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:319–326. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie M, Longabaugh R. Interpersonal factors and post-treatment drinking and subject well-being. Addiction. 1997;92:1507–1521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, P. L. (1992). Religion and substance use. In J. F. Schumaker (Ed.), Religion and mental health (pp. 211–221). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Berkman L, Syme S. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L. (1985). The relationship of social networks and social support to morbidity and mortality. In S. Cohen and S. Syme (Eds.), Social support and health Orlando, FL: Academic Press, pp. 241–262.

- Bollen, K. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Brady M, Peterman A, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P, Moos R. Life stressors, social resources, and late-life problem drinking. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:491–501. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogly S, Mercier C, Bruneau J, Palepu A, Franco E. Towards more effective public health programming for injection drug users: Development and evaluation of the injection drug user quality of life scale. Substance Use and Misuse. 2003;38:965–992. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman S. The challenge of sobriety: Natural recovery without treatment and self-help programs. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:41–61. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Caldwell P, Cutter H. Alcoholics anonymous affliction during early recovery. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15:221–28. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan G, Caplan R. Principles of community psychiatry. Community Mental Health J. 2000;36:7–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1001894709715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson V, Green H. Spiritual well-being: A predictor of hardiness in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Journal of Professional Nursing. 1992;8:209–20. doi: 10.1016/8755-7223(92)90082-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R. (1991). Middle recovery: An introspective journey. Addiction and Recovery, Sept–October, 8–12.

- Chappel J. Long term recovery from alcoholism. Psychiatric Clin N Amer. 1993;169:17–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]