Abstract

Mobile group II introns have been used to develop a novel class of gene targeting vectors, targetrons, which employ base pairing for DNA target recognition and can thus be programmed to insert into any desired target DNA. Here, we have developed a targetron containing a retrotransposition-activated selectable marker (RAM), which enables one-step bacterial gene disruption at near 100% efficiency after selection. The targetron can be generated via PCR without cloning, and after intron integration, the marker gene can be excised by recombination between flanking Flp recombinase sites, enabling multiple sequential disruptions. We also show that a RAM-targetron with randomized target site recognition sequences yields single insertions throughout the Escherichia coli genome, creating a gene knockout library. Analysis of the randomly selected insertion sites provides further insight into group II intron target site recognition rules. It also suggests that a subset of retrohoming events may occur by using a primer generated during DNA replication, and reveals a previously unsuspected bias for group II intron insertion near the chromosome replication origin. This insertional bias likely reflects at least in part the higher copy number of origin proximal genes, but interaction with the replication machinery or other features of DNA structure or packaging may also contribute.

INTRODUCTION

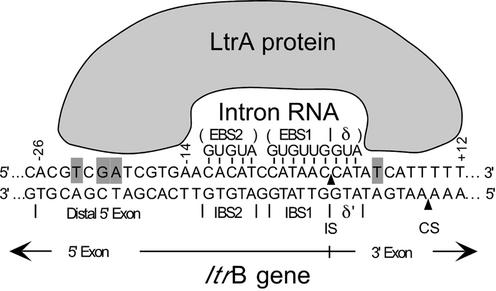

Mobile group II introns are retroelements that encode reverse transcriptases (RTs) and insert into specific DNA target sites at high frequency by a process termed retrohoming (1,2). The retrohoming reactions are carried out by a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that is formed during RNA splicing and consists of the intron-encoded protein (IEP) and the excised intron lariat RNA (3–7). This RNP initiates mobility by recognizing a specific double-stranded DNA target site, with both the IEP and base pairing of the intron RNA contributing to DNA target site recognition (Fig. 1) (6,8). The IEP first recognizes a small number of ‘fixed’ positions in duplex DNA, triggering local DNA unwinding, which enables the intron RNA to base pair to the adjacent 14–16 nt DNA sequence (7). These base pairing interactions involve three short sequence elements in the DNA target site [intron-binding sites 1 and 2 (IBS2 and IBS1) and δ′], which are recognized by complementary sequence elements [exon-binding sites 1 and 2 (EBS1 and EBS2) and δ] in the intron RNA (see Fig. 1). The intron RNA then inserts directly into one strand of the DNA by reverse splicing, while the IEP cleaves the opposite strand and uses the cleaved 3′ end as a primer for reverse transcription of the inserted intron RNA. The resulting intron cDNA is integrated by host DNA recombination or repair enzymes (9–11).

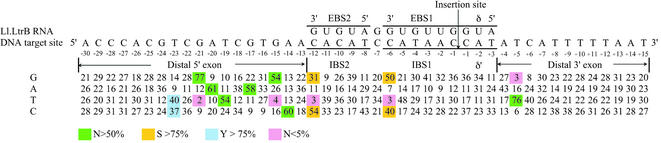

Figure 1.

Mechanism of DNA target site recognition by the L.lactis Ll.LtrB group II intron. The DNA target site in the ltrB gene is recognized by a RNP complex containing the IEP (LtrA protein) and excised intron lariat RNA, with both protein interactions and base pairing of the intron RNA contributing to DNA target site recognition (7,8). According to the model based on detailed DNA footprinting and modification-interference analysis, the IEP first recognizes a small number of specific bases, including T–23, G–21 and A–20, in the distal 5′ exon region of the DNA target site, via major groove interactions. These base interactions bolstered by phosphate-backbone interactions from positions –24 to –13 trigger local DNA unwinding, enabling the EBS1, EBS2 and δ sequences in the intron RNA to base pair with the IBS1, IBS2 and δ′ sequences in the DNA target site (positions –12 to +3). The intron RNA then inserts directly into one strand of the DNA by reverse splicing. Second strand cleavage occurs after a lag and requires additional interactions between the IEP and the 3′ exon, including recognition of T+5 in the 3′ exon. Bases identified as being recognized directly by the LtrA protein are highlighted. The arrowheads pointing to the top and bottom strands indicate the intron insertion site (IS) and the second strand cleavage site (CS), respectively.

Because the DNA target site is recognized primarily by base pairing of the intron RNA, it has been possible to develop group II introns into a new class of gene targeting vectors, ‘targetrons’, which can be programmed to insert into any desired target DNA (12,13). Previously, we showed that a targetron based on the mobile Lactococcus lactis Ll.LtrB intron could be used for highly specific chromosomal gene disruption and site-specific DNA insertion in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (13,14). Without selection, chromosome gene disruption frequencies in Escherichia coli were typically 0.1–1%. The ‘fixed’ positions recognized by the IEP are sufficiently flexible that computer programs readily identify multiple potential target sites in each gene. In addition to site-specific insertion, we showed that a targetron in which the RT activity had been inactivated by mutation could be used to generate double-strand breaks at specific chromosomal DNA locations, enabling the introduction of point mutations by homologous recombination with a co-transformed DNA fragment (13).

Here, we have constructed a targetron with a retrotransposition-activated selectable marker (RAM) that makes possible one-step bacterial gene disruption at near 100% efficiency after selection. Further, we show that a RAM-targetron with randomized target site recognition sequences yields single insertions at sites throughout the E.coli genome, creating a gene knockout library. In addition to providing further insight into target site recognition rules, analysis of the randomly selected insertion sites reveals a previously unsuspected bias for group II intron insertion near the replication origin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and selection conditions

Escherichia coli HMS174(DE3) (F– recA hsdR RifR) (Novagen, Madison, WI) was used for intron mobility assays and gene disruption experiments and DH5α was used for cloning. For selections, trimethoprim was added at 10 µg/ml and thymine was added at 1 µg/ml to M9 minimal medium and 2 µg/ml to Mueller–Hinton medium. Ampicillin and chloramphenicol were added at 100 and 25 µg/ml, respectively.

Recombinant plasmids

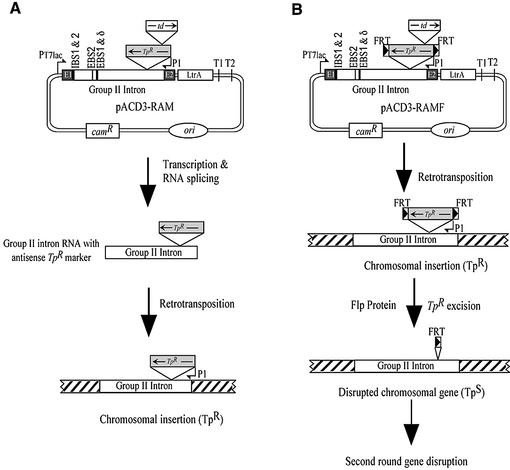

The targetron construct, pACD3-RAM, was derived from intron donor plasmid pACD3 (13) by inserting a RAM into group II intron domain IV. The marker consists of a reverse orientation trimethoprim resistance (TpR) gene disrupted by a forward orientation self-splicing td group I intron (Fig. 2). The TpR gene, encoding a type II dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), was amplified by PCR of plasmid R751 (15) with primers AGTACGCGTAGTTGACATAAGCCTGTTCG and AGTA CGCGTCAGGCCACACGTTCAAGCGCAGCCACA. After deleting 5′-UTR positions +22 to +250 from the transcription start site by an additional PCR, the insert was cloned into the MluI site in domain IV of the Ll.LtrB-ΔORF intron. The self-splicing td intron (10) was inserted at a non-essential site near the N-terminus of the DHFR ORF (16), with modifications of the DHFR sequence to ensure efficient td intron splicing (+6CCAACACA → +6G↓ACCCAAGAAA, changes underlined and arrow indicating the td intron insertion site). In pACD3-RAMF, the FRT sequence GAAGTTCCTATTCTCTAGAAAGTATAGGAACTTC was added to both ends of the TpR marker gene via PCR, prior to cloning into pACD3. pACD3-RAM-PCR was derived from pACD3-RAM by deleting positions –18 to +289 from the Ll.LtrB intron 5′ splice site, generating an EcoRV site. To determine mobility frequencies in plasmid assays, the RAM and RAMF cassettes were cloned into the MluI site of the T7 promoter-containing Ll.LtrB intron in pACD2 (12,13; see below).

Figure 2.

RAM-targetron constructs. (A) pACD3-RAM is a derivative of pACD3, which contains a 0.9 kb Ll.LtrB-ΔORF group II intron and flanking exons, with the intron-encoded protein, LtrA, expressed from a position downstream of the 3′ exon (12,13). pACD3-RAM contains a streamlined (313 bp) TpR marker gene with its promoter (P1) inserted in the group II intron domain IV in the orientation opposite intron transcription. The TpR marker is disrupted by a self-splicing td group I intron inserted in the forward orientation. During retrotransposition via an RNA intermediate, the td intron is spliced, activating the TpR marker, which is then selected after the intron has integrated into a DNA target site. (B) pACD3-RAMF is a modification of pACD3-RAM, which contains Flp recombinase recognition (FRT) sites flanking the TpR marker gene. Expression of Flp from the pBAD promoter in pMAK-Flp leads to efficient excision of the TpR marker from the integrated targetron, enabling multiple sequential disruptions. The figure shows the locations of the IBS1, IBS2, EBS2, EBS1 and δ sequences (black boxes), which are modified to retarget the intron to different locations. ori, P15A replication origin of pACYC184 vector.

The RAM-targetron library was constructed by PCR to randomize target site recognition sequences EBS2 (positions –12 to –8), EBS1 (–6 to –1) and δ (+1 to +3), as well as the corresponding IBS2 and IBS1 positions in the 5′ exon for efficient RNA splicing, as described previously for pACD2 libraries (12,13).

pMAK-Flp, which expresses Flp recombinase under the control of the pBAD promoter, was constructed by recloning a 3.1 kb segment of pBAD33-Flp (17) into pMAK705 (18) via PCR with primers TCCCCCGGGCATAATGTGCCTGTCAAATG and TCCCCCGGGATACATATTTGAATGTA TTTAG. The 3081 bp PCR product was digested with SmaI and cloned between the blunted AseI and Bsu36I sites of pMAK705.

Group II intron mobility assays and chromosomal gene disruption

Group II intron mobility frequencies were determined by using an E.coli two-plasmid assay in which an Ll.LtrB intron containing a phage T7 promoter near its 3′ end inserts into a target site upstream of a promoterless tetR gene, thereby activating that gene. The assays were as described (12,13), except that 500 µM IPTG and 30°C were used instead of 100 µM IPTG and 37°C.

For chromosomal gene disruption, targetrons containing the RAM TpR marker gene were transformed into E.coli HMS174(DE3) and grown overnight in LB medium containing chloramphenicol. An aliquot of 50 µl of the culture was then inoculated into 5 ml of fresh medium containing chloramphenicol and grown at 37°C until OD598 = 0.2. IPTG was added to 500 µM and cells were induced for 2 h at 30°C. The cells were then pelleted, resuspended in 5 ml of M9 minimal medium without antibiotics, plated on M9 containing trimethoprim plus thymine and incubated at 30°C for 2–3 days. Alternatively, to enrich for disruptants, 1 ml of the IPTG-induced cells was added to 20 ml of M9 medium containing trimethoprim plus thymine and grown to saturation at 30°C, prior to plating.

For sequential disruptions using pACD3-RAMF, the targetron donor plasmid used to obtain the first disruption was cured by plating on LB containing 100 µM IPTG and restreaking to identify a chloramphenicol-sensitive colony. The latter was then grown up in LB and transformed with pMAK-Flp. Flp recombinase was induced with 0.4% l-arabinose for 2 h at 30°C and the cells were plated on LB medium containing chloramphenicol. After checking cells for excision of the TpR marker gene, pMAK-Flp was cured by plating on LB at 42°C.

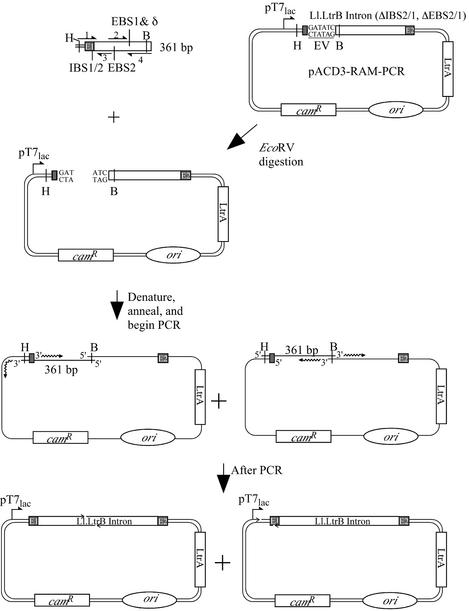

Generation of targetrons by PCR

A 361 bp DNA fragment containing modified IBS1/IBS2, EBS2 and EBS1/δ sequences was generated by a two-step PCR as described (13), then combined with EcoRV-digested pACD3-RAM-PCR by an additional PCR, yielding a non-covalently closed donor plasmid, which was transformed directly into E.coli. Alternatively, the 361 bp PCR product and pACD3-RAM were both digested with HindIII + BsrGI and then ligated with T4 DNA ligase (400 U) (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) for 1 h at room temperature, prior to transformation.

Southern hybridization

Escherichia coli chromosomal DNA was isolated by the CTAB–NaCl mini-prep method (19). Southern hybridization was as described (20), using a 32P-labeled probe for the retrotransposed intron generated via PCR with primers TCTTGCAAGGGTACGGAGTA and GTAGGGAGGTACCGCCTTGTTC, using a High Prime DNA Labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Random chromosomal insertions

After transformation with the RAM-targetron library, cells were grown to log phase at 37°C in LB medium, diluted 1:25 and grown for 20 h at 30°C in fresh LB containing 500 µM IPTG, and then for 5 h at 37°C in fresh LB containing 100 µM IPTG to induce targetron transcription and simultaneously promote donor plasmid loss. The cells were then washed and plated on Mueller–Hinton medium containing trimethoprim plus thymine, which was found to be essential for the selection with a chromosomally integrated TpR gene. For inverse PCR, genomic DNA was isolated from TpR CamS colonies (>80% of total TpR colonies) grown up in 1 ml of LB, digested with BsrFI + BsaWI (New England Biolabs) and religated. Inverse PCR was carried out using primers GATTCTCGGCATCGCTTTCG and ATTGTTTTCTTGGGTCTCCAT. Gel purified PCR products were sequenced, and integration sites were identified by BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Targetron vectors containing a retrotransposition-activated selectable marker

Figure 2 shows the RAM-targetron constructs used in this work. The constructs are based on a previously described intron donor plasmid pACD3, which contains a 0.9 kb ΔORF derivative of the L.lactis Ll.LtrB intron with flanking exons, cloned behind a T7lac promoter in a pACYC184-derived vector (13). The ORF encoding the IEP (denoted LtrA protein) is deleted from its original location in intron domain IV and expressed from a position just downstream of the 3′ exon. The protein expressed from this position promotes efficient RNA splicing and intron mobility, leading to insertion of the ΔORF intron at a new DNA location. In the absence of the IEP, the ΔORF intron is unable to splice after insertion at the new location and thus yields a gene disruption, regardless of intron orientation.

The RAM strategy is based on one first used to study yeast Ty1 transposition (21) and subsequently adapted to study group II intron transposition to ectopic sites by Belfort and co-workers (22). In this strategy, a selectable marker with its own promoter is inserted in the reverse orientation into group II intron domain IV, but is disrupted by an efficiently self-splicing td group I intron in the forward orientation (Fig. 2). During targetron retrotransposition via an RNA intermediate, the td group I intron is spliced, activating the genetic marker, which is then selected after DNA integration. In the construct shown, the selectable marker is a trimethoprim-resistant (TpR) DHFR gene carried originally by the broad host range plasmid R751 (15). This marker was chosen because its small size (313 nt after deletion of the 5′-UTR) mitigates effects on intron mobility frequency (∼20% wild type in an E.coli plasmid assay; data not shown).

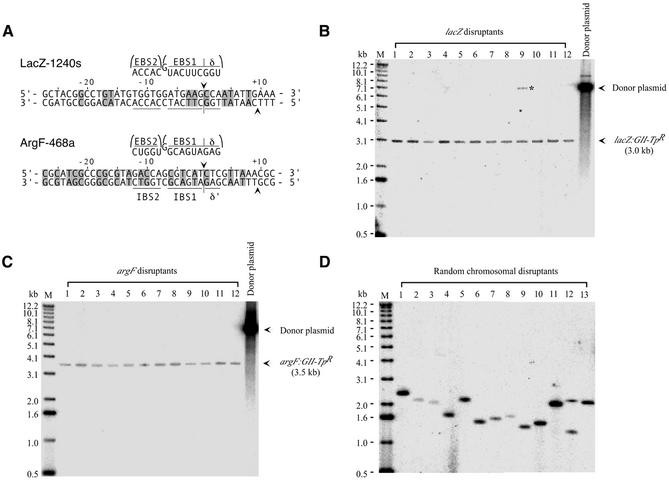

To test the RAM system, we used group II introns LacZ-1240s and ArgF-468a, whose EBS and δ sequences have been modified to insert specifically into the E.coli lacZ and argF genes (Fig. 3A). In the absence of selection, these introns insert into their lacZ and argF target sites at frequencies of 0.067 and 0.83%, respectively (13; data not shown). pACD3-RAM constructs containing LacZ-1240s and ArgF-468a were transformed into E.coli HMS174(DE3), which contains an IPTG-inducible T7 RNA polymerase. After induction of targetron transcription with IPTG, cells were plated on minimal medium containing trimethoprim, yielding TpR colonies at frequencies of 4.2 ± 0.8 × 10–7 and 2.3 ± 0.1 × 10–6, respectively (two repeats). Because the TpR marker is inactive prior to retrotransposition, it was not necessary to cure the donor plasmid before selecting TpR colonies, a major advantage compared to previous gene disruption approaches using selectable markers. For the LacZ targetron, 93/100 TpR colonies replated on X-gal medium were white, indicative of lacZ disruption, and correct insertion was confirmed for 10/10 white colonies by PCR and sequencing across the intron–exon junction. For the ArgF-468a targetron, 110/126 TpR colonies analyzed by PCR had the correct disruption, and 10/10 were confirmed by sequencing. Alternatively, when IPTG-induced transformants were grown to saturation in liquid culture containing trimethoprim to enrich for insertions prior to plating, 100% of the colonies had the expected disruption. Southern hybridizations showed that the targetron disruptions obtained by both approaches were highly specific, with a single band corresponding to the inserted targetron and no additional non-specific insertions (Fig. 3B and C).

Figure 3.

Disruption of E.coli chromosomal genes using RAM-targetron constructs. (A) Group II introns targeted to insert into the E.coli lacZ and argF genes. Group II intron LacZ-1240s inserts at position 1240 in the sense (s) strand of the lacZ ORF and ArgF-468a inserts at position 468 in the antisense (a) strand of the argF ORF. The introns were constructed by identifying the best matches to the ‘fixed’ positions recognized by the IEP and then modifying the intron EBS2, EBS1 and δ sequences to base pair to target site positions –12 to –8, –6 to –1, and +1 to +3, respectively, for the EBS/IBS and δ/δ′ interactions (12,13). The targeted introns were cloned into the pACD3-RAM donor plasmid modified to contain complementary IBS1 and IBS2 sequences in the 5′ exon to ensure efficient RNA splicing. The figure shows target sites and base pairing interactions for the retargeted introns. Nucleotide residues that match the wild-type target site are shaded. (B and C) Southern blots showing disruption of the chromosomal lacZ and argF genes by the retargeted group II introns. DNAs isolated from randomly chosen disruptants were digested with AatII + ApaLI, which linearizes the donor plasmid without cutting within the intron, and Southern blots were hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe specific for the retrotransposed intron. Lanes 1–10 contain DNAs from 10 randomly chosen disruptants from an experiment in which TpR colonies were selected directly on plates; lanes 11 and 12 contain DNAs from two disruptants in which cells were grown to saturation in liquid culture containing trimethoprim prior to plating. The left lane contains 5′-labeled DNA markers (M) and the right lane contains linearized donor plasmid. The lacZ disruptant in lane 9 still contains a trace amount of donor plasmid (asterisk). (D) Southern blots of random chromosomal disruptants obtained using a RAM-targetron library with randomized target site recognition sequences. DNAs isolated from 13 randomly chosen TpR colonies were digested with BsaWI + BsrFI and analyzed as above.

A targetron with an excisible marker permits multiple gene disruptions

To adapt the system for multiple gene disruptions, we constructed a modified RAM-targetron in which the TpR gene is flanked by FRT sites recognized by the site-specific recombinase Flp (23) (Fig. 2B). The addition of the FRT sites reduced the mobility frequency of the targetron in the E.coli plasmid assay by ∼50%. First, we transformed the LacZ-1240s targetron containing the FRT-flanked RAM marker into E.coli HMS174(DE3) and selected TpR colonies to obtain lacZ disruptants as above. After curing the targetron donor plasmid by growth in IPTG, we introduced a temperature-sensitive plasmid expressing Flp recombinase (pMAK-Flp), leading to 100% excision of the inserted TpR marker gene, as indicated by reversion to trimethoprim sensitivity and confirmed by PCR (data not shown). We then cured pMAK-Flp by growing at 42°C and repeated the process with the ArgF-468a targetron to obtain the desired lacZ argF double disruptants. In principle, this procedure can be applied to obtain strains with as many disruptions as desired.

Generation of the targetron via PCR without cloning

For high throughput approaches, it is desirable to generate the targetron constructs rapidly. We showed previously that targetrons designed by using a computer program could be generated by a two-step PCR procedure, using three unique primers and one fixed primer (13). The initial PCR yields a 361 bp product with modified target site recognition sequences and complementary 5′ exon sequences required for efficient RNA splicing, and the second PCR combines the 361 bp product with the vector backbone to yield a non-covalently closed circular PCR product corresponding to the targetron donor plasmid. The latter can be transformed directly into bacteria. Here, we used a vector backbone generated by restriction enzyme digestion, eliminating one of the PCR steps (Fig. 4). The LacZ-1240s and ArgF-468a RAM-targetrons generated by this method yielded TpR colonies at frequencies of 2.8 × 10–7 and 1.1 × 10–6, respectively, and X-gal plating and colony PCR showed that 97–100% had the desired gene disruption. We also obtained similar results by simply ligating the HindIII + BsrGI-digested 361 bp PCR product and vector backbone and then transforming the crude ligation mixture directly into E.coli (LacZ-1240s, 2.9 × 10–7, 93% disruptions; ArgF-468a, 1.2 × 10–6, 100% disruptions).

Figure 4.

PCR method for generating targetron constructs. A 361 bp linear DNA (top) corresponding to the 5′ exon and 5′ end of the Ll.LtrB group II intron was generated by a two-step PCR using two pairs of partially overlapping primers (primers 1 and 3 and primers 2 and 4) to introduce modifications into IBS1/2 (primer 1), EBS2 (primer 2) and EBS1/δ (primer 4). Primer sequences were: primer 1, AAAAAAGCTTCGTCGATCGGAANNNNNNNNNNNNGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG; primer 2, CGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTNNNNNTCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT; primer 3, AACCGAAATTAGAAACTTGCGTTCA; primer 4, CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCNNNNNNNNNAACTTACCTTTCTTTGT (N indicates nucleotide residues that are changed to retarget the intron to specific genes). The 361 bp PCR product is then used as a megaprimer for a second PCR with a 6.7 kb vector backbone generated by EcoRV digestion of pACD3-RAM-PCR. The final PCR product contains gaps (arrowheads) at different positions, depending on the strand of the 361 bp linear DNA from which priming occurred. EV, EcoRV site; B, BsrGI site; H, HindIII site; ori, P15A replication origin of pACYC184 vector.

Random chromosomal insertions

In another new approach analogous to global transposon mutagenesis, we used a RAM-targetron library in which the intron target site recognition sequences (EBS2, –12 to –8; EBS1, –6 to –1; δ, +1 to +3) were randomized to obtain targetrons integrated at different sites in the E.coli genome. After transformation of the library into E.coli HMS174(DE3), TpR colonies were obtained at a frequency of 3.6 × 10–6. Analysis of insertion sites in 96 colonies by inverse PCR and DNA sequencing showed that the targetron had integrated at 90 different sites (Supplementary Material Table S1). Of these 90 sites, 85 are located in 78 different genes and five are in intergenic regions. Southern hybridizations showed that 12/13 TpR colonies had a single intron insertion, with only one having a double insertion (Fig. 3D). Thus, the method generates a library of single gene knockouts potentially useful for functional genomic analysis.

Group II intron target site recognition rules

The sequences of the insertion sites and integrated targetrons selected from the library provide additional insight into protein and base pairing interactions required for targetron integration. For discussion, the DNA target site can be divided into three parts: the distal 5′ exon region (positions –30 to –13), recognized by the IEP to initiate mobility; the IBS/δ′ region (positions –12 to +3), recognized by base pairing of the intron RNA; the distal 3′ exon region (positions +4 to +15), recognized by the IEP for second strand cleavage (7,8).

Figure 5 summarizes nucleotide frequencies at positions –30 to +15 of the 90 sequenced targetron insertion sites. Alignments showed no strongly conserved nucleotide residues outside this region. In agreement with previous results, most of the conserved nucleotide residues recognized by the IEP are in the distal 5′ exon region of the DNA target site (7,8,12). Positions at which specific nucleotide residues were selected in >50% of the integration events include Y–23, G–21 and A–20, which are recognized via major groove interactions, position –19, the site of a phosphate-backbone interaction, and positions –17, –15 and –14, which are recognized either via minor groove interactions or via indirect readout of DNA structure (7). We showed previously that mutation or modification of these positions inhibits both the reverse splicing of the intron into the DNA target site and second strand cleavage (7,8). In the 3′ exon, the only strongly conserved nucleotide residue was T+5, which is required for second strand cleavage but not reverse splicing (7,8). Several other target site positions in both the 5′ and 3′ exons showed weaker positive biases, and there were also significant negative biases at some positions. Surprisingly, the nucleotide residues selected at positions –18, –17 and –14 differ from those in the wild-type target site, implying that the wild-type site itself has a suboptimal target sequence. None of the conserved nucleotide residues required for retrohoming was invariant, the most strongly conserved being G–21 and T+5, which were present in 77 and 76% of the target sites, respectively. Thus, there is significant redundancy or flexibility in the ‘fixed’ positions recognized by the IEP, a feature that facilitates identification of multiple target sites in any gene.

Figure 5.

Nucleotide frequencies at targetron insertion sites obtained using a RAM-targetron with randomized EBS and δ sequences. The figure summarizes nucleotide frequencies (%) at positions –30 to +15 in 90 different insertion sites in the E.coli genome. Strongly favored or disfavored nucleotide residues are highlighted: green, N > 50%; yellow, S (G + C) > 75%; blue, Y (C + T) > 75%; pink, N < 5%. We found no additional strongly favored or disfavored nucleotide residues from position –100 to +100 from the targetron insertion site.

Significantly, the 68 DNA target sites containing T+5, which is required for second strand cleavage, showed no substantial bias for insertion into the leading versus lagging template strands (36 leading/32 lagging), whereas those lacking T+5 showed a significant strand bias (15 leading/7 lagging for A, G or C, and 7 leading/1 lagging for G or C). These findings suggest that targetron insertions at sites lacking T+5 may occur in the absence of normal second strand cleavage by using the nascent leading strand as an alternative primer for reverse transcription. Ichiyanagi et al. (22) also noted a strand bias for Ll.LtrB transposition to ectopic sites, which can also occur by reverse splicing into DNA without second strand cleavage, but here, the strand bias suggested a preferential use of lagging strand primers for reverse transcription. These findings have significant implications for group II intron mobility mechanisms.

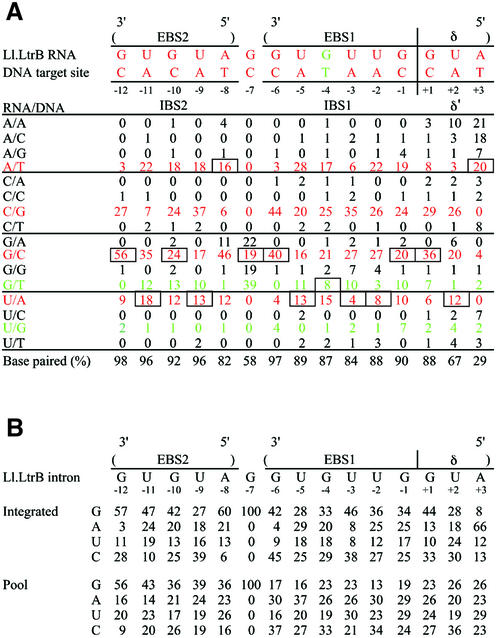

Base pairing interactions

The base pairing interactions between the intron RNA EBS/δ sequences and the DNA target site IBS/δ′ sequences could be inferred for 89 sites at which we obtained sequences of the EBS/δ regions of the integrated intron. The data, summarized in Figure 6A, show strong selection for base pairing at IBS2 positions –12 to –8, IBS1 positions –6 to –1 and δ′ +1, with weaker selection for base pairing with the target site at δ′ +2. The δ′ +3 position showed no selection for base pairing, but did show selection for retention of the wild-type A residue in the intron RNA, as judged by comparision of base composition at this position in the integrated introns and the initial targetron library (Fig. 6B). Several other positions in the intron RNA also showed significant positive or negative selection in the integrated introns, reflecting either preferences for specific base pairs or an effect on intron RNA structure. Position –7 was shown previously to be unpaired and the wild-type G residue corresponding to this position in EBS1 was not randomized in the targetron library (12,13). However, the randomly selected integration sites appeared to show some bias for a GT pair at this position (Fig. 6A). Finally, positions –12 and –6 at the beginning of IBS2 and IBS1 showed particularly strong selection for GC or CG pairs (83 and 84%, respectively), possibly to nucleate or anchor the formation of these duplexes. On the whole, there appears to be stronger selection for base pairing in EBS2/IBS2 than in EBS1/IBS1. These data, along with the nucleotide frequencies in the flanking regions, provide key information for the development of computer programs for designing efficiently targeted group II introns.

Figure 6.

Base pairing interactions at intron insertion sites obtained using a RAM-targetron library with randomized EBS and δ sequences, and base composition of the EBS/δ regions of the integrated introns and initial targetron donor library. (A) Base pairing interactions. The figure shows the frequency (%) of each base pair between the intron RNA and DNA target site for 89 integrated introns. Base pairing interactions between the wild-type Ll.LtrB intron and its normal ltrB DNA target site are shown at the top. Watson–Crick base pairs are shown in red and G/T or U/G wobble base pairs are shown in green. The wild-type base pair at each position is boxed. The percentage of Watson–Crick plus G/T or U/G wobble base pairs at each position is tabulated at the bottom. (B) Base composition at EBS1, EBS2 and δ positions in integrated introns and the initial intron donor library. The figure shows the frequency (%) of each nucleotide residue in the EBS2, EBS1 and δ regions of 89 integrated introns and 70 randomly chosen introns from the initial targetron donor library.

Distribution of targetron integration sites in the E.coli genome

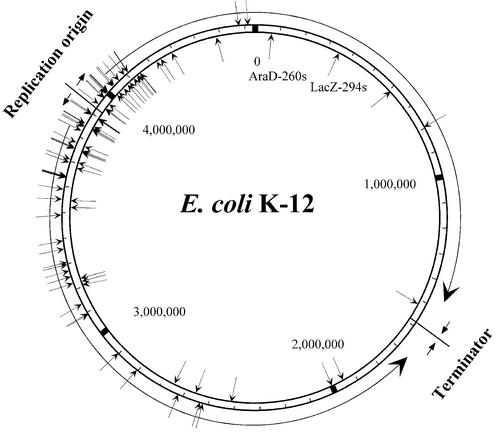

Figure 7 shows the distribution of the randomly selected targetron integration sites in the E.coli genome. Overall, the integration sites showed no strong strand bias (51 leading versus 39 lagging template) and those within genes showed no substantial transcription orientation bias (47 sense, 38 antisense). Remarkably, however, the integration sites were strongly clustered near the bidirectional replication origin (oriC), with 57% of the sites found within the 5% of the genome on either side of the origin (positions 3681887– 4151651).

Figure 7.

Distribution of targetron insertion sites in the E.coli genome. The map was compiled using the genome sequence of E.coli K-12 MG1655 (GenBank accession no. U00096) (31). The figure shows the bidirectional replication origin (oriC) and the terminator region, with the direction of replication indicated by arrows. Integration sites in the outside and inside strands are indicated by arrows pointing to the sites. The locations of the integrated LacZ-294s and AraD-260s introns amplified from the knockout library by PCR are also shown (see text).

The clustering of integration sites near oriC likely reflects, at least in part, that origin proximal regions are present in higher copy number than distal regions due to ongoing DNA replication. In rapidly dividing E.coli, this copy number difference can be as high as 4:1 (24) and may be increased further by abortive replications under some conditions (25). We found no disproportionate representation of the Ll.LtrB target sequence near the replication origin. Furthermore, the integration sites located within 5% of oriC do not contain disproportionate numbers of Dam or Dcm methylation sites, suggesting that hemimethylation of sites near the origin is not a factor (26), and we detected no correlation between the group II intron integration sites and IHF or DnaA protein-binding sites (27,28). It remains possible, however, that other features of DNA structure or packaging contribute to the skewed distribution or that the integration complex associates with replication factors, resulting in insertion early in the replication of the chromosome. Other transposons use a variety of different mechanisms for coordinating transposition with DNA replication (29,30; and references therein). Although the randomly selected targetron insertions were biased toward the chromosmal replication origin, the gene knockout library is sufficiently complex that insertions in poorly represented regions were detected readily by PCR (e.g. lacZ and araD) (Fig. 7). In principle, the integrated introns could be re-amplified from the knockout library by PCR and linked to a donor plasmid to obtain single knockouts in any gene.

Conclusions and prospects

In summary, our results establish a series of powerful new approaches for using targetrons based on mobile group II introns for targeted and random bacterial gene disruption. The targetron can be programmed to insert into a desired site with high specificity via modification of the group II intron EBS and δ sequences, or these sequences can be randomized to obtain insertions at randomly selected chromosomal sites for functional genomic analysis. Because the L.lactis Ll.LtrB intron functions efficiently in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, these approaches should be generally applicable to a wide variety of bacteria, using either the RAM-TpR marker gene described here or RAM versions of other selectable markers constructed by inserting the phage T4 td group I intron or other self-splicing introns. Targetrons do not require specialized strains or a highly efficient transformation procedure, can be transcribed by any RNA polymerase and are not dependent on host cell recombination functions (10,13). Although the distribution of non-targeted insertions in the E.coli genome is biased toward the replication origin, we envision that whole genome knockouts in any bacteria could be obtained rapidly by automated targeted insertion or by a combination approach in which an initial random knockout library is completed by automated, targeted insertion (A. Ellington, E. Marcotte and A.M. Lambowitz, in progress). In addition to these practical applications, our results provide additional insight into group II intron DNA target site recognition, suggest that a subset of group II intron retrohoming events may occur by using a DNA primer generated during DNA replication and reveal a previously unsuspected bias for group II intron insertion near the replication origin, with implications for group II intron mobility mechanisms.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Yuri Voziyanov and Makkuni Jayaram for plasmid pBAD33-Flp, Richard Meyer for plasmid R751 and Marlene Belfort, Andy Ellington, Kenji Ichiyanagi, Edward Marcotte and Jim Walker for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant GM37949.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambowitz A.M., Caprara,M.G., Zimmerly,S. and Perlman,P.S. (1999) Group I and group II ribozymes as RNPs: clues to the past and guides to the future. In Gesteland,R.F., Cech,T.R. and Atkins,J.F. (eds), The RNA World, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 451–484.

- 2.Belfort M., Derbyshire,V., Parker,M.M., Cousineau,B. and Lambowitz,A.M. (2002) Mobile introns: pathways and proteins. In Craig,N.L., Craigie,R., Gellert,M. and Lambowitz,A.M. (eds), Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp.761–783.

- 3.Zimmerly S., Guo,H., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1995) Group II intron mobility occurs by target DNA-primed reverse transcription. Cell, 82, 545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerly S., Guo,H., Eskes,R., Yang,J., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1995) A group II intron RNA is a catalytic component of a DNA endonuclease involved in intron mobility. Cell, 83, 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J., Zimmerly,S., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1996) Efficient integration of an intron RNA into double-stranded DNA by reverse splicing. Nature, 381, 332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo H., Zimmerly,S., Perlman,P.S. and Lambowitz,A.M. (1997) Group II intron endonucleases use both RNA and protein subunits for recognition of specific sequences in double-stranded DNA. EMBO J., 16, 6835–6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh N.N. and Lambowitz,A.M. (2001) Interaction of a group II intron ribonucleoprotein endonuclease with its DNA target site investigated by DNA footprinting and modification interference. J. Mol. Biol., 309, 361–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohr G., Smith,D., Belfort,M. and Lambowitz,A.M. (2000) Rules for DNA target-site recognition by a lactococcal group II intron enable retargeting of the intron to specific DNA sequences. Genes Dev., 14, 559–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eskes R., Yang,J., Lambowitz,A.M. and Perlman,P.S. (1997) Mobility of yeast mitochondrial group II introns: engineering a new site specificity and retrohoming via full reverse splicing. Cell, 88, 865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cousineau B., Smith,D., Lawrence-Cavanagh,S., Mueller,J.E., Yang,J., Mills,D., Manias,D., Dunny,G., Lambowitz,A.M. and Belfort M. (1998) Retrohoming of a bacterial group II intron: mobility via complete reverse splicing, independent of homologous DNA recombination. Cell, 94, 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eskes R., Liu,L., Ma,H., Chao,M.Y., Dickson,L., Lambowitz,A.M. and Perlman,P.S. (2000) Multiple homing pathways used by yeast mitochondrial group II introns. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8432–8446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo H., Karberg,M., Long,M., Jones,J.P.,3rd, Sullenger,B. and Lambowitz,A.M. (2000) Group II introns designed to insert into therapeutically relevant DNA target sites in human cells. Science, 289, 452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karberg M., Guo,H., Zhong,J., Coon,R., Perutka,J. and Lambowitz,A.M. (2001) Group II introns as controllable gene targeting vectors for genetic manipulation of bacteria. Nature Biotechnol., 19, 1162–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frazier C., San Filippo,J., Lambowitz,A.M. and Mills,D. (2003) Genetic manipulation of Lactococcus lactis using targeted group II introns: generation of stable insertions without selection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 69, 1121–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flensburg J. and Steen,R. (1986) Nucleotide sequence analysis of the trimethoprim resistant dihydrofolate reductase encoded by R plasmid R751. Nucleic Acids Res., 14, 5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews D.A., Smith,S.L., Baccanari,D.P., Burchall,J.J., Oatley,S.J. and Kraut,J. (1986) Crystal structure of a novel trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase specified in Escherichia coli by R-plasmid R67. Biochemistry, 25, 4194–4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voziyanov Y., Stewart,A.F. and Jayaram,M. (2002) A dual reporter screening system identifies the amino acid at position 82 in Flp site-specific recombinase as a determinant for target specificity. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 1656–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton C.M., Aldea,M., Washburn,B.K., Babitzke,P. and Kushner,S.R. (1989) New method for generating deletions and gene replacements in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 171, 4617–4622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ausubel F., Brent,R., Kingston,R., Moore,D., Seidman,J., Smith,J. and Struhl,K. (1989) Short Protocols in Molecular Biology, 3rd Edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

- 20.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY.

- 21.Curcio M.J. and Garfinkel,D.J. (1991) Single-step selection for Ty1 element retrotransposition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 936–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichiyanagi K., Beauregard,A., Lawrence,S., Smith,D., Cousineau,B. and Belfort,M. (2002) Retrotransposition of the Ll.LtrB group II intron proceeds predomantly via reverse splicing into DNA targets. Mol. Microbiol., 46, 1259–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broach J.R., Guarascio,V.R. and Jayaram,M. (1982) Recombination within the yeast 2 mµ circle is site-specific. Cell, 29, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper S. and Helmstetter,C. (1968) Chromosome replication and division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J. Mol. Biol., 31, 519–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altung T., Lobner-Olesen,A.L. and Hansen,F.G. (1987) Overproduction of DnaA protein stimulates initiation of chromosome and minichromosome replication in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet., 206, 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell J.L. and Kleckner,N. (1990) E. coli oriC and the dnaA gene promoter are sequestered from dam methyltransferase following the passage of the chromosomal replication fork. Cell, 62, 967–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujita M.Q., Yoshikawa,H. and Ogasawara,N. (1989) Structure of the dnaA region of Pseudomonas putida: conservation among three bacteria, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli and P. putida. Mol. Gen. Genet., 215, 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ussery D., Larsen,T.S., Wilkes,K.T., Friis,C., Worning,P., Krogh,A. and Brunak,S. (2001) Genome organisation and chromatin structure in Escherichia coli. Biochimie, 83, 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu W.Y. and Derbyshire,K.M. (1998) Target choice and orientation preference of the insertion sequence IS903. J. Bacteriol., 180, 3039–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters J.E. and Craig,N.L. (2001) Tn7 recognizes transposition target structures associated with DNA replication using the DNA-binding protein TnsE. Genes Dev., 15, 737–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blattner F.R., Plunkett,G.,3rd, Bloch,C.A., Perna,N.T., Burland,V., Riley,M., Collado-Vides,J., Glasner,J.D., Rode,C.K., Mayhew,G.F. et al. (1997) The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science, 277, 1453–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.