Abstract

The 6b gene in the T-DNA from Agrobacterium has oncogenic activity in plant cells, inducing tumor formation, the phytohormone-independent division of cells, and alterations in leaf morphology. The product of the 6b gene appears to promote some aspects of the proliferation of plant cells, but the molecular mechanism of its action remains unknown. We report here that the 6b protein associates with a nuclear protein in tobacco that we have designated NtSIP1 (for Nicotiana tabacum 6b–interacting protein 1). NtSIP1 appears to be a transcription factor because its predicted amino acid sequence includes two regions that resemble a nuclear localization signal and a putative DNA binding motif, which is similar in terms of amino acid sequence to the triple helix motif of rice transcription factor GT-2. Expression in tobacco cells of a fusion protein composed of the DNA binding domain of the yeast GAL4 protein and the 6b protein activated the transcription of a reporter gene that was under the control of a chimeric promoter that included the GAL4 upstream activating sequence and the 35S minimal promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus. Furthermore, nuclear localization of green fluorescent protein–fused 6b protein was enhanced by NtSIP1. A cluster of acidic residues in the 6b protein appeared to be essential for nuclear localization and for transactivation as well as for the hormone-independent growth of tobacco cells. Thus, it seems possible that the 6b protein might function in the proliferation of plant cells, at least in part, through an association with NtSIP1.

INTRODUCTION

Agrobacterium cells that harbor a Ti plasmid induce the formation of crown gall tumors on dicotyledonous plants. Upon infection of a plant by Agrobacterium, a specific region of the Ti plasmid, known as T-DNA, is transferred to the plant cell and integrated into the chromosomal DNA in the nucleus. Plant cells that have been transformed with T-DNA can proliferate autonomously to generate a tumor, which is a consequence, for the most part, of the expression of genes that are responsible for the biosynthesis of auxin; and cytokinin (iaaM [tms1] or iaaH [tms2] for auxin; ipt [tmr] for cytokinin) in the T-DNA (Weiler and Spanier, 1981; Akiyoshi et al., 1984).

In addition to these genes, gene 6b, which is localized at the tml locus (Garfinkel et al., 1981) and has been found in the T-DNA of all strains of Agrobacterium (Willmitzer et al., 1983; Otten and De Ruffray, 1994), also is expressed in tumor cells (Willmitzer et al., 1983) and appears to play a role in the proliferation of plant cells. Various phenotypic effects associated with the expression of 6b have been reported, as follows: (1) formation of tumors on certain plants (Hooykaas et al., 1988; Spanier et al., 1989; Tinland et al., 1989, 1992); (2) stimulation of the ipt-induced and iaaM/iaaH-induced division of cells (Tinland et al., 1989, 1990; Wabiko and Minemura, 1996); (3) reduction in the formation of shoots on leaf discs that is normally induced by appropriate levels of exogenous or endogenous cytokinin (Spanier et al., 1989); (4) generation of shoot-bearing calli on leaf discs on phytohormone-free medium (Wabiko and Minemura, 1996); (5) inhibition of the growth of Rol-induced hairy roots via the induction of an undifferentiated state and the formation of calli (Tinland et al., 1990); and (6) alterations in the morphology of leaves of transgenic tobacco plants that express the 6b gene (Tinland et al., 1992; Wabiko and Minemura, 1996). Although there are some discrepancies among previously reported results (Leemans et al., 1982; Ream et al., 1983), it is accepted generally that the product of 6b stimulates the proliferation of plant cells and affects the development of shoots and leaves by modulating the actions of cytokinin and/or auxin.

Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the effects of the 6b protein on cell proliferation and organ development. It has been suggested that the 6b gene might function in the activation and/or inactivation of cytokinin and auxin (Hooykaas et al., 1988; Spanier et al., 1989); it might increase and/or decrease the sensitivity of transformed cells to these plant hormones (Hooykaas et al., 1988; Tinland et al., 1989) by modifying putative hormone transport systems or reporters (Spanier et al., 1989); its product might interact with ipt and iaa genes and/or their products (Tinland et al., 1989) and/or it might stimulate signal perception systems (Wabiko and Minemura, 1996). It also has been proposed that the 6b gene might affect the concentration of endogenous plant hormones in transformed cells (Spanier et al., 1989). However, shoot-bearing calli of tobacco whose formation has been induced by the 6b gene contain normal levels of active cytokinins (Wabiko and Minemura, 1996). Moreover, when we consider the possible mechanisms of action of the 6b protein in plant cells, we must remember that, in chimeric plants that were generated by grafting the stem of a 6b-transformed plant onto that of a normal plant, the effect of 6b was found only in the 6b-transformed portion. Thus, the product of the 6b gene appears to be nondiffusible (Tinland et al., 1992). This conclusion is consistent with the hypothesis that the levels of cytokinin and auxin, which basically are diffusible within a plant, are not affected by expression of the 6b gene (Wabiko and Minemura, 1996).

Some clues to the mode of action of the 6b protein might be found in its amino acid sequence. However, there are no obvious motifs in 6b that are suggestive of a particular cellular function, even though there is a cluster of acidic amino acid residues near the C terminus (Levesque et al., 1988). Such clusters of acidic residues suggest interactions with other proteins to generate complexes that might be involved, for example, in transcription (Gill and Ptashne, 1987; Erard et al., 1988; Xue et al., 1993). The remaining sequence of the 6b protein is homologous, to some extent, to the sequences of a number of proteins that are encoded by genes in T-DNAs, such as the iaa, rol, ORF13, and ORF14 genes in Ti and Ri plasmids. It has been proposed that these genes belong to the plast family (Levesque et al., 1988) and cause the abnormal growth and morphology of roots and shoots (Cardarelli et al., 1987; Spena et al., 1987; Lemcke and Schmülling, 1998). The molecular mechanisms by which these genes generate abnormalities are unknown, except in the case of the iaa and ipt genes.

Investigations in animals of oncogenicity that is caused by pathogenic factors such as the Rb and E1A proteins have contributed to our understanding of the mechanisms of cell proliferation and differentiation in animal systems (Nevins, 1991; Shikama et al., 1997). To date, there have been few similar investigations in plant systems. Studies of the functions of the typical oncogenes iaa (tms) and ipt (tmr) (Barry et al., 1984; Inzé et al., 1984; Schröder et al., 1984) demonstrated the significance of endogenous auxin and cytokinin in both cell division and the differentiation of plant organs. Although plant homologs of animal oncogenes, such as Rb and myb, have been identified (Grafi et al., 1996; Xie et al., 1996; Ach et al., 1997; Kranz et al., 1998; Nakagami et al., 1999), the oncogenic activities of these genes have not been reported. An understanding of the role of the 6b gene might provide new clues to the molecular mechanisms of proliferation and differentiation in plant cells.

In designing the present study, we postulated that the 6b protein might affect some process in the induction of cell division via interactions with a plant protein. We screened a tobacco cDNA library in an effort to identify candidate 6b-interacting proteins. We isolated several cDNA clones and characterized a cDNA that encoded a putative transcription factor, designated NtSIP1 (for Nicotiana tabacum 6b–interacting protein 1). We then demonstrated that NtSIP1 was localized in the nuclei of tobacco cells and enhanced the nuclear localization of 6b. Furthermore, we found that 6b activated transcription in tobacco cells. We propose that NtSIP1 might be responsible for some of the phenotypic effects of the 6b gene.

RESULTS

Acidic Region of the 6b Protein Is Required for Callus Formation and Shoot Regeneration on Hormone-Free Medium

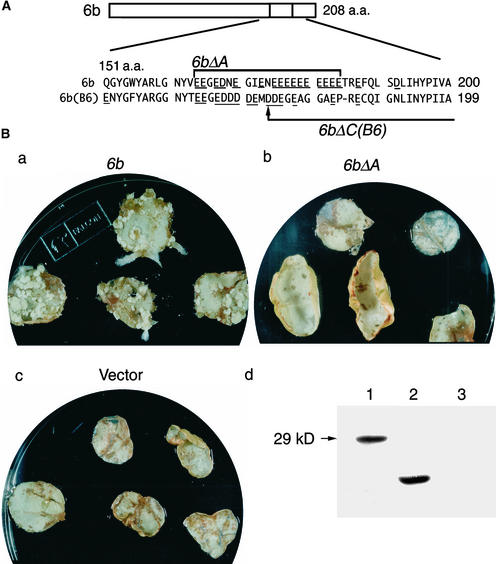

We first examined whether the acidic region of the 6b protein is required for cell growth on phytohormone-free medium. In all of the experiments described in this article, with the exception of the experiment described in the next section, we used the 6b gene from pTiAKE10 for our analysis because the formation of calli in response to the 6b gene from pTiAKE10 on hormone-free medium was more efficient than that in response to the 6b genes from other Ti plasmids (Spanier et al., 1989; Wabiko and Minemura, 1996). Hereafter, for simplicity's sake, we refer to the 6b gene from pTiAKE10 simply as 6b. We constructed a His and T7 epitope–tagged 6b gene and a similar 6bΔA gene, in which the entire acidic region (residues 164 to 184) had been deleted (His-T7-6b and His-T7-6bΔA, respectively) (Table 1, Figure 1A). These constructs were linked to the 35S promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus (P35S) in the binary vector pBI121. Each fusion gene was introduced into cells of leaf discs of tobacco. Shoot-bearing calli were generated on phytohormone-free medium from leaf discs that had been transformed with the His-T7-6b gene within 3 weeks (Figure 1Ba). In contrast, no calli were generated on phytohormone-free medium from His-T7-6bΔA–transformed leaf discs and from discs transformed with the vector pBI121 (Figures 1Bb and 1Bc). As shown in Figure 1Bd, the amount of His-T7-6bΔA protein synthesized in tobacco cells was similar to that of the His-T7-6b protein. We also examined a mutation in the region adjacent to the acidic region for its effect on hormone-independent growth. The mutation resulted in the same phenotype as His-T7-6b (data not shown). These results indicated that the C-terminal acidic region of 6b was necessary for the induction of shoot-bearing calli on phytohormone-free medium.

Table 1.

Plasmids Used in This Study

| Plasmid | Relevant Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Binary vectors for transformation of tobacco | ||

| p121-HT6b | Derivative of pBI121 (Jefferson et al., 1987) containing His-T7-6b DNA |

This study (Figure 1) |

| p121-HT6bΔA | Derivative of pBI121 containing His-T7-6bΔA DNA | This study (Figure 1) |

| Vectors for protein synthesis in tobacco cells | ||

| p221-HT6b | Derivative of pBI221 (Jefferson et al., 1987) containing His-T7-6b DNA |

This study (Figure 1) |

| p221-HT6bΔA | Derivative of pBI221 containing His-T7-6bΔA DNA | This study (Figure 1) |

| Bait vector for the two-hybrid system screening | ||

| pLexA-6bΔC(B6) | Derivative of pBTM116 containing 6bΔC(B6) DNA | This study (data not shown) |

| Vectors for the two-hybrid system assays | ||

| pGLexA-NtSIP1 | Derivative of pGilda (OriGene Technology, Inc., Rockville, MD) containing cNtSIP1 under the control of the GAL1-inducible promoter | This study (Figure 2) |

| pB42AD-6b | Derivative of pB42AD (Clontech) containing B42AD-6b DNA under control of the GAL1-inducible promoter |

This study (Figure 2) |

| pB42AD-6bΔA | Derivative of pB42AD containing B42AD-6bΔA DNA under the control of the GAL1-inducible promoter |

This study (Figure 2) |

| Vectors for protein synthesis in Escherichia coli | ||

| pET-HT6b | Derivative of pET28 containing His-T7-6b DNA | This study (Figure 4) |

| pET-HT6bΔA | Derivative of pET28 containing His-T7-6bΔA DNA | This study (Figure 4) |

| pET-H6b | Derivative of pET28 containing His-6b DNA | This study (Figure 4) |

| pET-HTNtSIP1 | Derivative of pET28 containing His-T7-cNtSIP1 | This study (Figure 4) |

| pET-HTNRK1 | Derivative of pET28 containing His-T7-cNRK1 | Unpublished data (Figure 4) |

| Vectors for cellular localization studies | ||

| psGFP | Derivative of pBI221 containing a gene for sGFP under the control of P35S and Ω sequences |

Chiu et al., 1996 (Figures 3 and 5) |

| pNLS-sGFP | Derivative of pBI221 containing NLS:sGFP DNA | Chiu et al., 1996 (Figures 3 and 5) |

| psGFP-NtSIP1 | Derivative of pBI221 containing sGFP:cNtSIP1 DNA | This study (Figure 3) |

| psGFP-6b | Derivative of pBI221 containing sGFP:6b DNA | This study (Figure 5) |

| psGFP-6bΔA | Derivative of pBI221 containing sGFP:6bΔA DNA | This study (Figure 5) |

| p221-NtSIP1 | Derivative of pBI221 containing cNtSIP1 | This study (Figure 5) |

| Vectors for transactivation assays | ||

| pGALDBD | Derivative of pBI221 containing GAL4 DNA binding domain (GALDBD) DNA |

This study (Figure 6) |

| pGALDBD-6b | Derivative of pBI221 containing GALDBD:6b DNA | This study (Figure 6) |

| pGALDBD-6bΔA | Derivative of pBI221 containing GALDBD:6bΔA DNA | This study (Figure 6) |

| pGALUAS35S-Luc | Derivative of pBI221 containing the firefly gene for luciferase under the control of a chimeric promoter composed of the GAL4 UAS and the 35S minimal promoter |

This study (Figure 6) |

| p221-RLuc | Derivative of pBI221 containing the Renilla gene for luciferase |

This study (Figure 6) |

See text for details and abbreviations.

Figure 1.

The Acidic Region of the 6b Protein Is Essential for the Hormone-Independent Formation of Callus and the Interaction with NtSIP1.

(A) Scheme of the structure of the 6b protein. The amino acid (a.a.) sequences around the acidic regions (positions 151 to 200) of 6b and 6b(B6), which were derived from pTiAKE10 and pTiB6S3trac, respectively, are shown below the domain organization. The region deleted in the 6bΔA mutant is indicated by a bracket, and the deletion point at residue 174 in the 6bΔC(B6) mutant is indicated by an arrow. Acidic amino acid residues are underlined.

(B) The hormone-independent formation of shoot-bearing calli from tobacco leaf discs requires the acidic region of 6b. Tobacco leaf discs were infected with Agrobacterium cells that harbored the pBI121 vector plasmid with the His-T7-6b gene (a), the His-T7-6bΔA gene (b), or no additional gene (c) and cultured on phytohormone-free medium for 21 days. (d) shows a protein gel blot of the His-T7-6b and His-T7-6bΔA proteins synthesized in BY-2 cells. Protein extracts were prepared from BY-2 cells that had been transfected with pBI221 that included the His-T7-6b gene (lane 1) or the His-T7-6bΔA gene (lane 2) or with the empty vector (lane 3). Ten micrograms of total protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE, electroblotted, and analyzed by protein gel blotting with anti-T7 antibodies.

Isolation of cDNAs for 6b-Interacting Proteins by Screening with the Yeast Two-Hybrid System

To isolate tobacco cDNAs for 6b-interacting proteins, we screened a cDNA library prepared from tobacco Bright Yellow 2 (BY-2) cells using the yeast two-hybrid system. We first examined the potential background transcriptional activity of 6b proteins in yeast cells. The DNA fragment encoding the DNA binding domain of LexA was fused with 6b genes from two types of Ti plasmid, pTiAKE10 and pTiB6S3trac, and the transcriptional activity of the product of each of the fusion genes was measured. The transcriptional activity of the product of the 6b gene derived from pTiB6S3trac [6b(B6)] was lower than that of the product of the 6b gene from pTiAKE10, even though 6b(B6) had some background activity (data not shown). To reduce the background still further, we introduced deletions in the region that encoded the acidic region of 6b and decided to use, as “bait,” the 6bΔC(B6) DNA construct, in which the DNA sequence corresponding to the C-terminal peptide from the middle of the acidic region to the C terminus had been deleted (residues 173 to 208) (Figure 1A). LexA-fused 6bΔC(B6) had low transcriptional activity in yeast and thus was suitable for screening with the two-hybrid system.

Using the truncated construct, we screened ∼4 × 106 independent yeast transformants and isolated 10 positive clones, which we divided into two groups after comparing the patterns of digestion by restriction enzymes of the inserts in the cDNA clones. The product of one of the cDNAs was designated NtSIP1, the cDNA was designated cNtSIP1, and the corresponding tobacco gene was designated NtSIP1.

Using the two-hybrid system, we next examined whether the acidic region of 6b was required for the interaction with NtSIP1. Because the LexA-fused 6b gene exhibited strong transcriptional activity in yeast cells, we fused the cDNA for NtSIP1 to the LexA sequence (LexA:cNtSIP1) to generate a bait construct and fused the 6b gene or the 6bΔA mutant gene to the B42AD transcriptional activator sequence (B42AD:6b or B42AD:6bΔA) to generate a “prey” construct. As shown in Figure 2, yeast cells that carried the B42AD:6b and the LexA:cNtSIP1 constructs were able to proliferate under restrictive conditions, but cells containing B42AD:6bΔA and LexA:cNtSIP1 were unable to grow. These observations suggested that the acidic region of the 6b protein was essential for the interaction with NtSIP1.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the Role of the Acidic Region of 6b in the Interaction of 6b with NtSIP1 Using the Yeast Two-Hybrid System.

cNtSIP1 Encodes a Nuclear Protein with a Triple Helix Motif

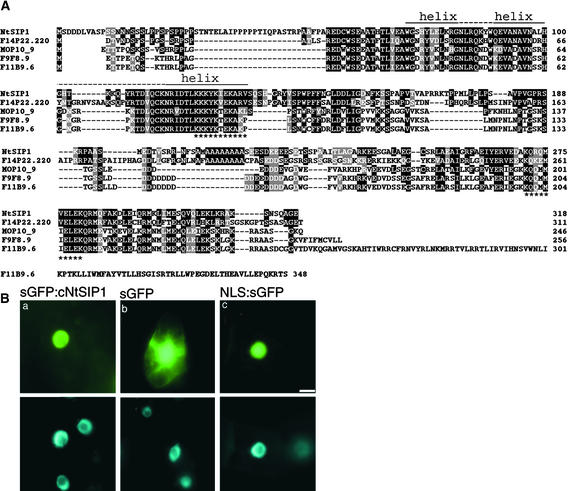

cNtSIP1 appeared to encode a polypeptide of 318 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of 34.8 kD. Predictions of secondary structure made by application of the Garnier algorithm (Garnier et al., 1978) indicated that the region from residue 72 to residue 131 of NtSIP1 formed three α-helices with short intervening loops (Figure 3A). This region was similar, in terms of amino acid sequence, to the triple helix motif of rice transcription factor GT-2, which controls the expression of the PHYA gene (Dehesh et al., 1992). In addition, we found two basic regions that resembled a nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Alignment of the Deduced Amino Acid Sequences of NtSIP1 and Homologs from Arabidopsis and the Nuclear Localization of NtSIP1.

(A) The deduced amino acid sequence of NtSIP1 is aligned with the sequences of F14P22.220, MOP10_9, F9F8.9, and F11B9.6 from Arabidopsis. The triple helix motif that is predicted to form amphipathic helices (helix) and intervening nonhelical regions (dotted lines above sequences) are indicated. Sequences that resemble NLS are indicated by asterisks. Residues are highlighted in white letters on black if NtSIP1 and other sequences have identical residues, and gray shading indicates similar residues at the same position.

(B) Subcellular localization of sGFP-NtSIP1 in BY-2 cells. Plasmids that carried P35S-linked sGFP:cNtSIP1 (a), P35S-linked sGFP (b), and P35S-linked NLS:sGFP (c) were introduced into BY-2 cells, and transfected cells were cultured for 16 hr at 26°C. Fluorescence was monitored with a fluorescence microscope (top panels). Nuclei stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) are shown in the bottom panels. Bar = 10 μm.

A computer-assisted homology search revealed that there are several homologs (F14P22.220, MOP10_9, F9F8.9, and F11B9.6) of the NtSIP1 gene in the genome of Arabidopsis (Figure 3A). The amino acid sequence of NtSIP1 was 43% identical to that of the predicted product of F14P22.220, 36% identical to that of MOP10_9, 34% identical to that of F9F8.9, and 27% identical to that of F11B9.6. A phylogenetic tree analysis indicated that NtSIP1 was related closely to F14P22.220 of Arabidopsis. The amino acid sequences of NtSIP1 and F14P22.220 aligned throughout the length of the proteins with several small gaps. Amino acid sequences corresponding to a triple helix motif and nuclear localization signals are conserved in all of these deduced sequences (Figure 3A).

We fused the cDNA for a modified form of green fluorescent protein (sGFP) (Chiu et al., 1996) to cNtSIP1 (sGFP:cNtSIP1) and linked the fused construct to P35S. We then introduced this chimeric gene into BY-2 cells for transient expression. We also introduced P35S-linked sGFP DNA alone and P35S-linked simian virus 40 NLS-fused sGFP DNA (NLS:sGFP) into BY-2 cells to serve as controls (simian virus 40 NLS DNA encodes a NLS of simian virus 40). As shown in Figure 3Ba, the sGFP-NtSIP1 protein was localized in the nuclei of tobacco cells. Moreover, as we had anticipated, sGFP was localized in both nuclei and the cytoplasm (Figure 3Bb), whereas the NLS-sGFP protein was localized only in nuclei (Figure 3Bc).

DNA gel blot analysis with genomic DNA from tobacco yielded a single band of DNA when the entire cNtSIP1 was used as a probe, suggesting that NtSIP1 is a single-copy gene (data not shown). We also examined the sites and levels of accumulation of NtSIP1 transcripts in normal tobacco plants. We found that NtSIP1 transcripts accumulated in roots, stems, mature leaves, and shoot apices, which included the shoot apical meristem, and levels of transcripts were significantly higher in shoot apices than in other organs (data not shown).

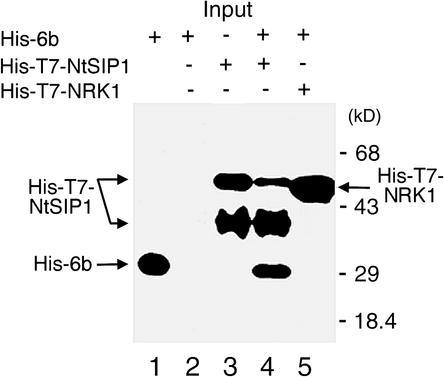

NtSIP1 Interacts with 6b in Vitro

We examined the possible association of 6b with NtSIP1 in vitro. His and T7 epitope–tagged NtSIP1 (His-T7-NtSIP1) and His epitope–tagged 6b (His-6b) proteins were produced in E. coli, and proteins were purified with nickel beads. The purified proteins were incubated together, and protein complexes were precipitated with T7-specific antibodies. The recovered complexes were subjected to protein gel blot analysis with His-specific antibodies. As shown in Figure 4, when His-6b and His-T7-NtSIP1 were mixed and protein complexes were exposed to T7-specific antibodies, a band of His-6b protein was detected in the immunocomplexes (lane 4). When either the His-6b or the His-T7-NtSIP1 protein alone was incubated with T7-specific antibodies, no band of the His-6b protein was detected (lanes 2 and 3). His-T7-NtSIP1 proteins were detected as two bands. We postulated that the band with lower mobility corresponded to intact His-T7-NtSIP1, whereas the band with higher mobility corresponded to a degradation product generated during the incubation. After incubation of His-6b with the His-T7-NRK1 mitogen-activated protein kinase as a negative control, no His-6b protein was recovered in the immunoprecipitate with T7-specific antibodies (lane 5). These results demonstrated that 6b interacted with NtSIP1 in vitro.

Figure 4.

Interaction between 6b and NtSIP1.

Appropriate combinations of recombinant proteins that had been produced in E. coli were immunoprecipitated with anti-T7 antibodies and subjected to protein gel blot analysis with His tag–specific antibodies. Details are given in the text. Lane 1, His-6b protein as a marker; lane 2, His-6b alone; lane 3, His-T7-NtSIP1 alone; lane 4, His-6b and His-T7-NtSIP1; lane 5, His-6b and His-T7-NRK1 (NRK1 is a mitogen-activated protein kinase that was used as a negative control; our unpublished data). Positions of these recombinant proteins are indicated by arrows. Two bands are apparent in the lane that corresponds to His-T7-NtSIP1: the band with greater mobility might represent a degradation product that was generated during immunoprecipitation.

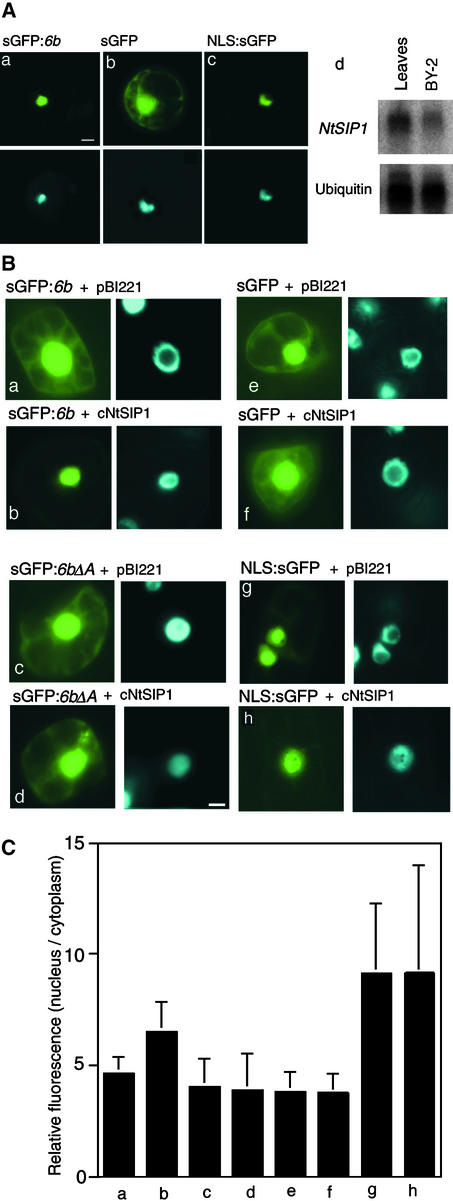

NtSIP1 Enhances the Nuclear Localization of the 6b Protein in Tobacco Cells

We examined the localization of sGFP-fused 6b protein in tobacco mesophyll cells. We prepared protoplasts from tobacco mesophyll cells into which we transiently introduced the P35S-linked sGFP:6b construct, sGFP DNA, and the NLS:sGFP construct, and then we examined the distribution of signals attributable to sGFP in the cells. As shown in Figure 5Aa, fluorescent signals from sGFP-6b were detected in nuclei, suggesting the nuclear localization of sGFP-6b in mesophyll cells. The fluorescent signals from sGFP, as a negative control, were detected in both the cytosol and the nuclei (Figure 5Ab), and those from NLS:sGFP, a positive control, were found only in the nuclei (Figure 5Ac).

Figure 5.

Cotransfection of BY-2 Cells with P35S-Linked sGFP:6b and P35S-Linked cNtSIP1.

(A) Nuclear localization of sGFP-6b in mesophyll protoplasts of tobacco. P35S-linked sGFP:6b (a), P35S-linked sGFP (b), and P35S-linked NLS:sGFP (c) were introduced into tobacco mesophyll protoplasts with polyethylene glycol. Fluorescence from sGFP (top panels) and from DAPI (bottom panels) was monitored with a fluorescence microscope. (d) shows an RNA gel blot showing the levels of transcripts of the NtSIP1 gene in leaves and BY-2 cells.

(B) Stimulation of the nuclear localization of the sGFP-6b protein by coexpression of NtSIP1. Gold particles that carried the indicated combinations of constructs were introduced into BY-2 cells by particle bombardment, and cells were cultured for 16 hr at 26°C. Fluorescence from sGFP (left panels) and DAPI (right panels) was monitored with a fluorescence microscope. Bar = 10 μm.

(C) Quantitative analysis of the nuclear localization of sGFP-6b. Results indicated by bars a through h correspond to the same panels in (B). We chose nine sGFP-positive cells at random in each experiment. Fluorescence per unit area of nuclei and per unit area of cytoplasmic regions was measured with the software program IPLab (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA), and average values with standard deviations were calculated for each experiment. Relative values were calculated by dividing the nuclear values by the cytoplasmic values.

The nuclear localization of sGFP-6b was not defined as clearly in suspension-cultured BY-2 cells (Figure 5Ba) as it was in mesophyll cells, perhaps because the level of expression of NtSIP1 in BY-2 cells was lower than that in mesophyll cells (Figure 5Ad). To examine this possibility, we cotransfected BY-2 cells transiently with P35S-linked sGFP:6b and P35S-linked cNtSIP1. As shown in Figures 5Ba and 5Bb, the relative intensity of fluorescence from sGFP-6b in nuclei was higher after cotransfection with P35S-linked cNtSIP1 (Figure 5Bb) than after cotransfection with the empty vector DNA (pBI221; Figure 5Ba). When BY-2 cells were cotransfected with P35S-linked sGFP:6bΔA and P35S-linked cNtSIP1, the relative intensity of fluorescence from P35S-linked sGFP:6bΔA in nuclei was similar to that from P35S-linked sGFP:6bΔA that had been used to cotransfect cells together with the empty vector (Figures 5Bc and 5Bd). Cotransfection with P35S-linked cNtSIP1 did not affect the relative intensity of fluorescence from sGFP or from NLS:sGFP in nuclei (Figures 5Be to 5Bh).

To quantify the relative intensities of fluorescence in nuclei, we chose nine cells at random in each experiment with a particular combination of genes. We measured the fluorescence per unit area of the nucleus and of a cytoplasmic region within each cell and calculated average values for each experiment. The average value from the nuclei was divided by that from the cytoplasmic region to provide a relative value in each case (Figure 5C). The relative value for cells that expressed sGFP:6b and cNtSIP1 (Figure 5C, bar b) was higher than that for cells that expressed sGFP:6b alone (Figure 5C, bar a), sGFP:6bΔA alone (Figure 5C, bar c), or sGFP alone (Figure 5C, bar e) and also was higher than that for cells that coexpressed sGFP:6bΔA and cNtSIP1 (Figure 5C, bar d) or sGFP and cNtSIP1 (Figure 5C, bar f). The relative values for cells that expressed NLS:sGFP were highest, and these values were unaffected by cNtSIP1 (Figure 5C, bars g and h).

These results indicated that NtSIP1 enhanced the nuclear localization of sGFP-6b in BY-2 cells and that the acidic region of 6b was necessary for the enhancement of the nuclear localization of sGFP-6b.

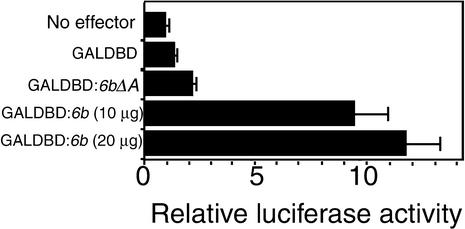

A Fusion Protein Composed of the DNA Binding Domain of Yeast GAL4 and 6b Activates Transcription in Tobacco Cells

As described above, the 6b protein exhibited strong transcriptional activity in yeast cells. We determined whether this protein also could function as a transcriptional activator in tobacco cells using the yeast GAL4 expression system (Yamamoto et al., 1998). For construction of the effector gene, we fused the DNA sequence that encoded the GAL4 DNA binding domain (GALDBD) to the 6b gene (GALDBD:6b) or to the 6bΔA gene (GALDBD:6bΔA) and then linked these constructs to P35S. We also constructed a reporter gene in which the coding sequence of the gene for firefly luciferase was linked to a GALDBD-inducible promoter, which consisted of six tandem repeats of the upstream activating sequence (UAS) of the GAL4 promoter and a minimal 35S promoter (GALUAS35S:LUC). As an internal control, we used the luciferase gene from Renilla under the control of P35S. Plasmid DNAs containing effector, reporter, and internal control genes were introduced into protoplasts of BY-2 cells, and after a 24-hr incubation, protein extracts were prepared from the cells and the luciferase activities of each extract were measured. As shown in Figure 6, the relative activity of the extract from cells transfected with the GALDBD:6b gene as an effector was six to eight times that of the extract from cells transfected with GALDBD as a negative control. GALDBD-6bΔA was not associated with a similarly high level of reporter luciferase activity (Figure 6). These results showed that the GALDBD-6b protein was capable of activating transcription and that the acidic region of 6b was required for activation.

Figure 6.

Transactivation Activity of the GALDBD-Fused 6b Protein.

Control GALDBD, effector GALDBD:6bΔA, and GALDBD:6b genes were introduced individually with the GALUAS35S:LUC reporter gene and a reference reporter gene (luciferase gene from Renilla) into protoplasts of BY-2 cells by polyethylene glycol–mediated transfection. After culture for 24 hr, luciferase activities were assayed as described in the text. The activity of firefly luciferase was normalized in each case by reference to the activity of the reference luciferase. The average results of five independent determinations with standard deviations were calculated, and values given are relative to the activity obtained without an effector gene.

DISCUSSION

6b Protein Affects the Transcription of Plant Genes

The present study showed that the 6b protein encoded by the T-DNA of Agrobacterium can associate with the nuclear protein NtSIP1 of tobacco (Figures 2, 4, and 5) and that 6b was itself localized in the nuclei of plant cells (Figure 5). It seems likely that the NtSIP1 protein is a transcription factor because it includes two NLS-like sequences and a sequence that is similar to that of the triple helix motif of rice transcription factor GT-2 (Figure 3), a protein that binds to the GT box in the phyA promoter (Dehesh et al., 1992). In addition, the GALDBD-6b protein induced the expression of a reporter gene that was driven by a GAL4 UAS-fused promoter in BY-2 cells (Figure 6). The 6b protein included a cluster of acidic amino acid residues near its C terminus, and this cluster was necessary for the interaction of 6b with NtSIP1, for transactivation of the reporter gene by 6b, and for generation of shoot-bearing calli by 6b in the absence of exogenous plant hormones (Figure 1). Our observations suggest that the 6b protein in plant cells might affect the transcription of certain plant genes directly, which might induce at least some of the phenotypic abnormalities that are known to be associated with the expression of 6b, as described in the Introduction. Genes controlled by NtSIP1 might be candidates for such genes. Thus, the present study provides a new paradigm for the action of a gene that is introduced into plant cells upon infection by a pathogenic bacterium. Full understanding of the roles and actions of NtSIP1 requires further experimentation. The present results do not exclude possible roles for 6b in the cytoplasm, because we did detect 6b in the cytoplasm of plant cells as well as in the nuclei.

Experiments with GAL4 fusion proteins demonstrated that a protein encoded by the avirulence (avr) gene avrXa10 of Xanthomonas oryzae can activate transcription in plant cells and that the acidic region of AvrXa10 is required for both transcriptional activation and avirulence activity (Zhu et al., 1998, 1999). To date, there is no experimental evidence that the avirulence protein enters the plant nucleus, but it seems likely that this protein should affect the transcription of plant genes, which in turn would induce a hypersensitivity reaction.

Role of the Interactions of 6b with Plant Proteins Such as NtSIP1 in Phenotypic Expression

NtSIP1 enhanced the nuclear localization of sGFP-fused 6b (Figure 5), which has no obvious signal for nuclear localization. Thus, it is conceivable that NtSIP1 might form a complex with 6b in the cytoplasm immediately after the synthesis of 6b, with the complex then being transported into the nucleus as a result of the NLS in NtSIP1. Alternatively, 6b might enter the nucleus by passive diffusion and might be trapped there by NtSIP1. Proteins of <40 kD can pass through nuclear pores by simple diffusion (Kaffman and O'Shea, 1999).

Regardless of the actual mechanism of the nuclear localization of 6b, the existence of NtSIP1, a nuclear protein that interacts with 6b, suggests that the efficiency of the nuclear localization of 6b might depend on cellular levels of all 6b-interacting proteins, including NtSIP1, and such levels also might depend on the specific type of cell or tissue. In this regard, it is noteworthy that sGFP-6b accumulated much more efficiently in the nuclei of mesophyll cells than in the nuclei of BY-2 cells. This might have been caused by differences in the total amounts of 6b-interacting proteins between the two types of cells.

As described in Results, we isolated a second 6b-interacting protein, designated NtSIP2, which remains to be characterized in detail. We also found recently that a tobacco transcription factor with an obvious DNA binding motif interacted with 6b (data not shown). It seems likely that there are several 6b-interacting proteins in plants and that the phenotypes generated by the expression of 6b might depend on the types of 6b-interacting protein.

6b. Protein Might Function as a Transcriptional Coactivator/Mediator or as a Repressor

The 6b protein did not include any obvious DNA binding motif, but it did include an acidic region that is required for its interaction with NtSIP1 and for the activation of transcription by 6b. Thus, 6b might function as a transcriptional coactivator/mediator by interacting with other proteins in the transcriptional machinery. In mammalian cells, proteins encoded by viral genomes, such as VP16 of Herpes simplex and E1A of adenovirus, can activate the transcription of cellular genes (Nevins, 1991). The 6b protein, which apparently interacted with NtSIP1, seems to be similar to VP16 and E1A in terms of its effects on transcription, because these viral proteins have no DNA binding motifs and bind to various cellular DNA binding proteins, such as Oct-1 and Rb, respectively (Whyte et al., 1988; Stern et al., 1989). It is possible that 6b might act to repress transcription by depleting or inactivating positive regulators. E1A is bifunctional with respect to transcription: it operates as an activator in the transcription of early viral genes (Nevins, 1991), whereas it represses transcription of the gene for cyclin D1 (Philipp et al., 1994).

The functions of NtSIP1 might be affected by 6b, but functional interactions between these proteins remain to be examined. The functions of NtSIP1 in plant growth and development under normal conditions also need to be clarified. The accumulation of NtSIP1 transcripts in the shoot apex is consistent with a role in plant growth. In addition, it will be of interest to determine whether there might be a relationship between the functions of this protein and the actions of phytohormones. “Reverse genetics,” using transgenic tobacco plants that express sense and antisense cDNAs, as well as dominant inhibitory cDNAs, might be helpful in approaching these problems. We also have been studying Arabidopsis and have found that transgenic Arabidopsis plants that carried the 6b gene exhibited various developmental abnormalities, including leaf curling, serration, and dwarfism (our unpublished data). A computer-assisted homology search revealed that there were several homologs of genes for NtSIP1 in the Arabidopsis genome. Among them, the predicted amino acid sequence from F14P22.220 exhibited the strongest similarity to that of NtSIP1 (Figure 3). The functions of this hypothetical protein remain to be determined, and mutational analysis of this and similar genes might provide further clues to the functions of NtSIP1.

METHODS

Plant Materials

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv SR1), used as the host for transformation, was grown on Murashige and Skoog (1962) medium prepared with 1% agar in light (3000 to 5000 lux) for 16 hr/day and in darkness for 8 hr/day at 26°C. Suspension cultures of the Bright Yellow 2 cell line of tobacco (BY-2 cells) were maintained as described previously (Banno et al., 1993).

Transformation

Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 was used for plant transformation. Tobacco leaf discs were transformed using previously described procedures (An et al., 1986) and then cultured on Murashige and Skoog medium that contained carbenicillin (300 mg/L) and kanamycin (200 mg/L) without auxin and cytokinin.

Construction of Plasmids

Plasmids and their relevant characteristics are listed in Table 1. All manipulations for construction of plasmids were performed using standard techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989). Escherichia coli DH10B was used as host for the construction of plasmids. To verify the nucleotide sequences of constructs, the DNA in critical regions was sequenced with the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using an Applied Biosystems 310 Genetic Analyzer. We used 6b genes from two types of Ti plasmid, pTiB6S3trac (Shimoda et al., 1993) and pTiAKE10 (Wabiko and Minemura, 1996) and designated them 6b(B6) and 6b, respectively. The DNA with deletion of codons 164 to 184 of the 6b gene was generated by polymerase chain reaction and designated 6bΔA.

For screening by the yeast two-hybrid system, DNA with a deletion from codon 173 to codon 208 of the 6b(B6) gene was generated by polymerase chain reaction and designated 6bΔC(B6); it was inserted in a modified form of pBTM116 (Vojtek et al., 1993). Details of procedures for the construction of other plasmids for transactivation assays will be supplied upon request. Also upon request, all of the plasmid constructs described in this article will be made available for noncommercial research purposes.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

Screening was performed basically as described by Vojtek et al. (1993). A cDNA library was synthesized from poly(A)+ RNA that had been isolated from BY-2 cells at the midlogarithmic phase of growth by the standard protocol with a cDNA synthesis kit from the SuperScript plasmid system (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Double-stranded DNAs were inserted into a modified form of the pVP16 plasmid, and the plasmid library was introduced into cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae L40 (Vojtek et al., 1993). Approximately 4 × 106 transformants were screened on plates without histidine, and 10 positive clones were isolated. Sequencing analysis showed that nine of the inserts originated from the same mRNA and that one insert was unique. The unique cDNA corresponded to the NtSIP1 gene. The inserts were rescued from the yeast clones by the standard method.

Interactions between 6b and NtSIP1 in Yeast

To examine the interactions between 6b and NtSIP1 by the yeast two-hybrid system, we used S. cerevisiae EGY48 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Yeast cells were cotransformed with a combination of pGLexA plus pB42AD-6b or plus pB42AD-6bΔA and with a combination of pGLexA-NtSIP1 plus pB42AD-6b or pB42AD-6bΔA. For analysis of cell growth, yeast cells were streaked on complete minimal “dropout” medium without histidine and tryptophan to confirm transformation with both plasmids. Then, cells were restreaked on medium that lacked histidine, tryptophan, and leucine but that contained galactose as a carbon source to test for leucine auxotrophy.

Preparation of Protoplasts and Assays of Transcriptional Activation

Protoplasts were isolated from BY-2 cells as described previously (Onouchi et al., 1991). Polyethylene glycol–mediated transfection was performed and mesophyll protoplasts were isolated as described by Bilang et al. (1994).

For assays of transcriptional activation, cells were incubated for 24 hr in darkness at 26°C and then subjected to enzymatic assays as described in the instructions from the manufacturer of the assay system (Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System; Promega, Madison, WI). The assay of firefly luciferase activity was initiated by adding 20 μL of a solution of extracted protein to 100 μL of Luciferase Assay Reagent II. Quenching of the luminescence of firefly luciferase and concomitant activation of Renilla luciferase for normalization were accomplished by adding Stop and Glo reagent in Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System to the sample tube immediately after quantitation of the activity of the firefly luciferase. Luciferase activities were measured with a photomultiplier as described elsewhere (Kondo et al., 1993).

Subcellular Localization of sGFP-Fused 6b and sGFP-Fused NtSIP1

BY-2 cells in a 500-μL culture at the midlogarithmic phase of growth were collected on a nitrocellulose filter (pore size, 5 μm; JM-type filter; Nihon Millipore, Yonezawa, Japan) and subjected to microprojectile bombardment with a PIG device (model GIE-III; Tanaka Co., Ltd., Sapporo, Japan) or treated with polyethylene glycol (see above) to introduce the sGFP:6b plasmid (5 μg) and the sGFP: cNtSIP1 plasmid (5 μg) or other plasmids as indicated in Figures 3 and 5. The cells then were transferred to fresh medium and incubated for 16 hr. The fluorescence from modified green fluorescent protein was monitored as described elsewhere (Nishihama et al., 2001).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins and Immunochemical Analysis

Recombinant fusion proteins were produced in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The proteins were affinity purified on chelating Sepharose Fast-Flow gels (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo, Japan). Eluates were dialyzed against 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, plus 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol and concentrated with an Ultrafree-4 centrifugal filter unit (Nihon Millipore). His-T7-NRK1 (NRK1 is a member of the tobacco family of mitogen-activated protein kinases) was produced in E. coli and purified similarly (a gift from T. Soyano, Nagoya University, Japan). Two kinds of recombinant protein (0.5 μg each) were mixed in 100 μL of binding buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% [w/v] Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% [v/v] glycerol, and 0.5 mg/mL BSA) and allowed to interact for 90 min at 4°C. Beads of T7 tag–specific antibody-conjugated agarose (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) were added to each binding reaction, and mixtures were rotated gently at 4°C for 90 min. Agarose beads then were washed three times with the binding buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in loading buffer for SDS-PAGE and then subjected to protein gel blot analysis (Sambrook et al., 1989) with His-specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Accession Numbers

The accession numbers for the sequences shown in Figure 3 are AB072391 (NtSIP1), CAB68201 (F14P22.220), AAK73993 (MOP10_9), AAF01512 (F9F8.9), and AAG50987 (F11B9.6).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Chiyoko Machida for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by a grant for the Research for the Future Program from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. JSPS-RFTF 97L00601) and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (No. 10182101) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sports of Japan. T.F. and Y.U. were supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.010360.

References

- Ach, R.A., Durfee, T., Miller, A.B., Taranto, P., Hanley-Bowdoin, L., Zambryski, P.C., and Gruissem, W. (1997). RRB1 and RRB2 encode maize retinoblastoma-related proteins that interact with a plant D–type cyclin and geminivirus replication protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5077–5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyoshi, D.E., Klee, H., Amasino, R.M., Nester, E.W., and Gordon, M.P. (1984). T-DNA of Agrobacterium tumefaciens encodes an enzyme of cytokinin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 5994–5998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An, G., Watson, B.D., and Chiang, C.C. (1986). Transformation of tobacco, tomato, potato, and Arabidopsis thaliana using a binary Ti vector system. Plant Physiol. 81, 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno, H., Hirano, K., Nakamura, T., Irie, K., Nomoto, S., Matsumoto, K., and Machida, Y. (1993). NPK1, a tobacco gene that encodes a protein with a domain homologous to yeast BCK1, STE11, and Byr2 protein kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 4745–4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry, G.F., Rogers, S.G., Fraley, R.T., and Brand, L. (1984). Identification of a cloned cytokinin biosynthetic gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 4776–4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilang, R., Klöti, A., Schrott, M., and Potrykus, I. (1994). PEG-mediated direct gene transfer and electroporation. In Plant Molecular Biology Manual, Vol. A1, S.B. Gelvin, ed (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers), pp. 1–16.

- Cardarelli, M., Mariotti, D., Pomponi, M., Spanò, L., Capone, I., and Costantino, P. (1987). Agrobacterium rhizogenes T-DNA genes capable of inducing hairy root phenotype. Mol. Gen. Genet. 209, 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, W., Niwa, Y., Zeng, W., Hirano, T., Kobayashi, H., and Sheen, J. (1996). Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Curr. Biol. 6, 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehesh, K., Hung, H., Tepperman, J.M., and Quail, P.H. (1992). GT-2: A transcription factor with twin autonomous DNA-binding domains of closely related but different target sequence specificity. EMBO J. 11, 4131–4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erard, M.S., Belenguer, P., Caizergues-Ferrer, M., Pantaloni, A., and Amalric, F. (1988). A major nucleolar protein, nucleolin, induces chromatin decondensation by binding to histone H1. Eur. J. Biochem. 175, 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, D.J., Simpson, R.B., Ream, L.W., White, F.F., Gordon, M.P., and Nester, E.W. (1981). Genetic analysis of crown gall: Fine structure map of the T-DNA by site-directed mutagenesis. Cell 27, 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, J., Osguthorpe, D.J., and Robson, B. (1978). Analysis of the accuracy and implications of simple methods for predicting the secondary structure of globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 120, 97–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill, G., and Ptashne, M. (1987). Mutants of GAL4 protein altered in an activation function. Cell 51, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafi, G., Burnett, R.J., Helentjaris, T., Larkins, B.A., DeCaprio, J.A., Sellers, W.R., and Kaelin, W.G., Jr. (1996). A maize cDNA encoding a member of the retinoblastoma protein family: Involvement in endoreduplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 8962–8967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooykaas, P.J.J., der Dulk-Ras, H., and Schilperoort, R.A. (1988). The Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA gene 6b is an onc gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 11, 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzé, D., Follin, A., Van Lijsebettens, M., Simoens, C., Genetello, C., Van Montagu, M., and Schell, J. (1984). Genetic analysis of the individual T-DNA genes of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: Further evidence that two genes are involved in indole-3-acetic acid synthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 194, 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, R.A., Kavanagh, T.A., and Bevan, M.W. (1987). GUS fusions: β-Glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 6, 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffman, A., and O'Shea, E.K. (1999). Regulation of nuclear localization: A key to a door. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 291–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, T., Strayer, C.A., Kulkarni, R.D., Taylor, W., Ishiura, M., Golden, S.S., and Johnson, C.H. (1993). Circadian rhythms in prokaryotes: Luciferase as a reporter of circadian gene expression in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 5672–5676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz, H.D., et al. (1998). Towards functional characterisation of the members of the R2R3-MYB gene family from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemans, J., Langenakens, J., De Greve, H., Deblaere, R., Van Montagu, M., and Schell, J. (1982). Broad-host-range cloning vectors derived from the W-plasmid Sa. Gene 19, 361–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemcke, K., and Schmülling, T. (1998). Gain of function assays identify non-rol genes from Agrobacterium rhizogenes TL-DNA that alter plant morphogenesis or hormone sensitivity. Plant J. 15, 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, H., Delepelaire, P., Rouzé, P., Slightom, J., and Tepfer, D. (1988). Common evolutionary origin of the central portions of the Ri TL-DNA of Agrobacterium rhizogenes and the Ti T-DNAs of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Mol. Biol. 11, 731–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami, H., Sekine, M., Murakami, H., and Shinmyo, A. (1999). Tobacco retinoblastoma–related protein phosphorylated by a distinct cyclin-dependent kinase complex with Cdc2/cyclin D in vitro. Plant J. 18, 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevins, J.R. (1991). Transcriptional activation by viral regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 16, 435–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama, R., Ishikawa, M., Araki, S., Soyano, T., Asada, T., and Machida, Y. (2001). The NPK1 mitogene-activated protein kinase kinase kinase is a regulator of cell-plate formation in plant cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 15, 352–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onouchi, H., Yokoi, K., Machida, C., Matsuzaki, H., Oshima, Y., Matsuoka, K., Nakamura, K., and Machida, Y. (1991). Operation of an efficient site-specific recombination system of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii in tobacco cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 6373–6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten, L., and De Ruffray, P. (1994). Agrobacterium vitis nopaline Ti plasmid pTiAB4: Relationship to other Ti plasmids and T-DNA structure. Mol. Gen. Genet. 245, 493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp, A., Schneider, A., Väsrik, I., Finke, K., Xiong, Y., Beach, D., Alitalo, K., and Eilers, M. (1994). Repression of cyclin D1: A novel function of MYC. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 4032–4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream, L.W., Gordon, M.P., and Nester, E.W. (1983). Multiple mutations in the T region of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens tumor-inducing plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80, 1660–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Schröder, G., Waffenschmidt, S., Weiler, E.W., and Schröder, J. (1984). The T-region of Ti plasmids codes for an enzyme synthesizing indole-3-acetic acid. Eur. J. Biochem. 138, 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikama, N., Lyon, J., and La Thangue, N.B. (1997). The p300/CBP family: Integrating signals with transcription factors and chromatin. Trends Cell Biol. 7, 230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda, N., Toyoda-Yamamoto, A., Aoki, S., and Machida, Y. (1993). Genetic evidence for an interaction between the VirA sensor protein and the ChvE sugar-binding protein of Agrobacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 26552–26558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier, K., Schell, J., and Schreier, P.H. (1989). A functional analysis of T-DNA gene 6b: The fine tuning of cytokinin effects on shoot development. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219, 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spena, A., Schmülling, T., Koncz, C., and Schell, J.S. (1987). Independent and synergistic activity of rol A, B and C loci in stimulating abnormal growth in plants. EMBO J. 6, 3891–3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern, S., Tanaka, M., and Herr, W. (1989). The Oct-1 homoeodomain directs formation of a multiprotein-DNA complex with the HSV transactivator VP16. Nature 341, 624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinland, B., Huss, B., Paulus, F., Bonnard, G., and Otten, L. (1989). Agrobacterium tumefaciens 6b genes are strain-specific and affect the activity of auxin as well as cytokinin genes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Tinland, B., Rohfritsch, O., Michler, P., and Otten, L. (1990). Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA gene 6b stimulates rol-induced root formation, permits growth at high auxin concentrations and increases root size. Mol. Gen. Genet. 223, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinland, B., Fournier, P., Heckel, T., and Otten, L. (1992). Expression of a chimeric heat-shock-inducible Agrobacterium 6b oncogene in Nicotiana rustica. Plant Mol. Biol. 18, 921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtek, A.B., Hollenberg, S.M., and Cooper, J.A. (1993). Mammalian ras interacts directly with the serine/threonine kinase raf. Cell 74, 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wabiko, H., and Minemura, M. (1996). Exogenous phytohormone-independent growth and regeneration of tobacco plants transgenic for the 6b gene of Agrobacterium tumefaciens AKE10. Plant Physiol. 112, 939–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, E.W., and Spanier, K. (1981). Phytohormones in the formation of crown gall tumors. Planta 153, 326–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, P., Buchkovich, K.J., Horowitz, J.M., Friend, S.H., Raybuck, M., Weinberg, R.A., and Harlow, E. (1988). Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: The adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature 334, 124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmitzer, L., Dhaese, P., Schreier, P.H., Schmalenbach, W., Van Montagu, M., and Schell, J. (1983). Size, location and polarity of T-DNA-encoded transcripts in nopaline crown gall tumors: Common transcripts in octopine and nopaline tumors. Cell 32, 1045–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q., Sanz-Burgos, A.P., Hannon, G.J., and Gutiérrez, C. (1996). Plant cells contain a novel member of the retinoblastoma family of growth regulatory proteins. EMBO J. 15, 4900–4908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Z., Shan, X., Lapeyre, B., and Mélèse, T. (1993). The amino terminus of mammalian nucleolin specifically recognizes SV40 T-antigen type nuclear localization sequences. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 62, 13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Y.Y., Matsui, M., Ang, L.H., and Deng, X.W. (1998). Role of a COP1 interactive protein in mediating light-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 1083–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W., Yang, B., Chittoor, J.M., Johnson, L.B., and White, F.F. (1998). AvrXa10 contains an acidic transcriptional activation domain in the functionally conserved C terminus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11, 824–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W., Yang, B., Wills, N., Johnson, L.B., and White, F.F. (1999). The C terminus of AvrXa10 can be replaced by the transcriptional activation domain of VP16 from the Herpes simplex virus. Plant Cell 11, 1665–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]