Abstract

The present studies address the mechanism of aromatic hydroxylation used by the natural and G103L isoforms of the diiron enzyme toluene 4-monooxygenase. These isoforms have comparable catalytic parameters but distinct regiospecificities for toluene hydroxylation. Hydroxylation of ring-deuterated p-xylene by the natural isoform revealed a substantial inverse isotope effect of 0.735, indicating a change in hybridization from sp2 to sp3 for hydroxylation at a carbon atom bearing the deuteron. During the hydroxylation of 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene, similar magnitudes of intramolecular isotope effects and patterns of deuterium retention were observed from both isoforms studied, indicating that the active-site mutation affected substrate orientation but did not influence the mechanism of hydroxylation. The results with deuterated toluenes show inverse intramolecular isotope effects for hydroxylation at the position of deuteration, normal secondary isotope effects for hydroxylation adjacent to the position of deuteration, near-quantitative deuterium retention in m-cresol obtained from 4-2H1-toluene, and partial loss of deuterium from all phenolic products obtained from 3,5-2H2-toluene. This combination of results suggests that an active site-directed opening of position-specific transient epoxide intermediates may contribute to the chemical mechanism and the high degree of regiospecificity observed for aromatic hydroxylation in this evolutionarily specialized diiron enzyme.

Aromatic hydroxylation is an important metabolic process as evidenced by the reactions of heme-containing P450s, flavin monooxygenases, pterin-dependent nonheme monooxygenases, nonheme mononuclear iron dioxygenases, and diiron hydroxylases (1–4). Among the diiron hydroxylases, four catalytic subfamilies have been identified by biochemical and phylogenetic characterizations. The physiologically relevant substrates of these subfamilies are methane, phenols, toluene/benzene, and alkenes. Among these evolutionarily related enzymes, the four-protein toluene 4-monooxygenase complex (T4MO) catalyzes the NADH- and O2-dependent hydroxylation of toluene with uniquely high regiospecificity, yielding p-cresol as 96% of the total products (5). Furthermore, T4MO converts a wide variety of monosubstituted benzenes, including nitrobenzene, to para-hydroxylated products with similar high regiospecificity. Catalytically active isoforms of the T4MO hydroxylase (T4moH), including the G103L variant investigated here, have been produced by mutagenesis and shown to have kcat, kcat/KM, and coupling efficiencies comparable to the natural isoform even as the regiospecificity for aromatic hydroxylation has been redefined (5). These studies indicate the potential importance of substrate-binding orientations in producing the desired catalytic outcome but do not address specific details of the chemical mechanism of hydroxylation.

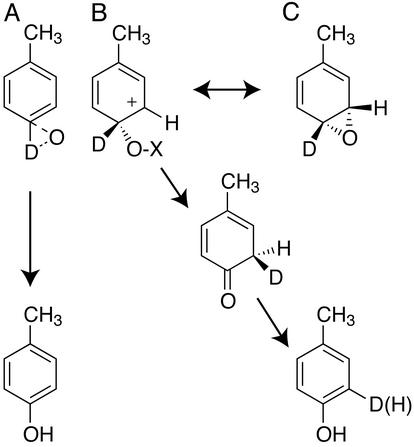

Fig. 1 summarizes frequently considered pathways for aromatic hydroxylation, which are insertion into the C—H bond (A), addition/rearrangement without obligatory formation of an epoxide intermediate (B), and initial formation of an epoxide intermediate (C). Pathways B and C are ultimately related by decomposition of the epoxide, which may either be enzyme-catalyzed or occur spontaneously. Under appropriate circumstances, the pathways of Fig. 1 can result in characteristic intramolecular isotope effects and deuterium-retention patterns. Thus an experimental paradigm to evaluate aromatic hydroxylation has been developed (6–8). This previous work provides a basis for the present investigation and an opportunity to compare mechanistic results among various aromatic hydroxylases.

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms for aromatic hydroxylation illustrated with 4-2H1-toluene. (A) Direct insertion of an electrophilic oxygen into a C—H bond. (B) Addition/rearrangement. (C) Epoxidation.

Two previous results with T4MO provide a starting point for comparison. First, partially purified preparations of T4MO were reported to give ≈70% retention of 2H in p-cresol obtained from 4-2H1-toluene (9). This high percentage of retention indicates that a direct insertion into the C—H bond (Fig. 1A) or H-atom abstraction are unlikely. Second, methyl-group migration has been detected during the oxidation of both p-xylene (10) and 4-fluorotoluene (11). These “NIH-shift” results are consistent with the generation of a cationic intermediate but do not distinguish between addition/rearrangement (Fig. 1B) or epoxidation (Fig. 1C). In this work, specifically deuterated p-xylene and toluene were studied to gain further insight into the chemical mechanism of hydroxylation. The results show that both natural T4moH and the G103L isoform give (i) inverse intramolecular isotope effects for hydroxylation at the position of deuteration, (ii) normal secondary isotope effects for hydroxylation adjacent to the position of deuteration, (iii) near-quantitative deuterium retention in m-cresol obtained from 4-2H1-toluene, and (iv) partial loss of deuterium in all phenolic products obtained from 3,5-2H2-toluene. This combination of results is consistent with the hypothesis that transient epoxide intermediates may contribute to the chemical mechanism and the high degree of regiospecificity observed for aromatic hydroxylation in T4moH.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

Except as indicated, chemicals were from Aldrich. NMR solvents were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Beverly, MA). Deuterated p-xylenes (>98% isotopic abundance) were from Isotec (Miamisburg, OH). N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) was from Pierce. Protein expression, purification, and characterization and the construction of the T4moH isoform G103L were as reported (5).

Substrate Syntheses.

4-2H1-toluene.

A Grignard reaction (12) was used to synthesize 4-2H1-toluene with a deuterium content of 81% as determined by GC/electron-ionization MS and 13C NMR.

3,5-2H2-toluene.

A method based on that reported for synthesis of 3,5-2H2-chlorobenzene was used (13), and a deuterium content of 92% was determined by GC/electron-ionization MS and 13C NMR.

Product-Distribution Reactions.

All reactions were performed in 250 μl of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, containing 4 nmol each of T4moC Rieske ferredoxin and T4moD effector protein, 0.4 nmol of T4moF reductase, 2 nmol of T4moH (αβγ protomer, corresponding to the active-site concentration), and 2,000 units of catalase (Sigma). Other methods were reported elsewhere (5). For product-distribution analyses, two aliquots were taken from each reaction and extracted into chloroform. One aliquot was analyzed without further derivatization, whereas the second aliquot was derivatized with MSTFA before analysis.

Product-Distribution Analyses.

A Hewlett–Packard 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with a 7683 auto injector and flame ionization detector (250°C) was used with a split ratio of 0.5:1. A BP20 column was used for studies of toluene and p-xylene (Scientific Glass Engineering, Austin, TX; 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm film; He carrier 4.0 ml/min; temperature program of 100–130°C at 5°C/min, 130–144°C at 2°C/min, 144–240°C at 30°C/min, and 240°C for 7 min). Under these conditions, benzyl alcohol and the o-, p-, and m-cresols eluted at 7.6, 10.4, 12.6, and 12.8 min, respectively. The p-xylene products 4-methylbenzyl alcohol, 2,5-dimethyl phenol, and 2,4-dimethyl phenol (methyl migration) eluted at 9.5, 12.7, and 12.8 min, respectively. The internal standard 3-methyl-benzyl alcohol eluted at 9.7 min. An EC-5 column was used for analysis of MSTFA-derivatized toluene products (Alltech Associates; 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm film; He carrier 5.0 ml/min; temperature program of 70°C for 2 min, 70–80°C at 1.5°C/min, 80–90°C at 2°C/min, 90°C for 2 min, 90–225°C at 40°C/min, and 225°C for 6 min). Under these conditions, o-, m-, and p-cresols and benzyl alcohol eluted at 9.4, 9.9, 10.4, and 10.5 min, respectively. The internal standard 3-methyl-benzyl alcohol eluted at 9.6 min.

Deuterium Content Analyses.

A Hewlett–Packard 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with a 5973 mass-selective detector (12-eV ionization energy) and 7683 auto injector (150°C) was used with a 20:1 split ratio for substrates and a 0.5:1 split ratio for products. An HP-5MS column was used for product analyses (Scientific Glass Engineering; 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm film thickness; He carrier 4.0 ml/min; temperature program of 70°C for 1 min, 70–75°C at 1°C/min, 75°C for 1 min, 75–90°C at 3°C/min, 90°C for 1 min, 90–110°C at 5°C/min, 110°C for 2 min, 110–250°C at 30°C/min, and 250°C for 10 min). The MSTFA-derivatized o-, m-, and p-cresols and benzyl alcohol eluted at 11.3, 11.8, 12.2, and 12.4 min, respectively. The same column was used to analyze 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene, which eluted in 3.6 min at 45°C.

Deuterium Retention.

For products obtained from 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene, the ratio of mass peak intensities for m/z values of {(n − 1)/[n + (n − 1)]} was calculated and then corrected to account for the 2H content in the synthesized substrate. For 4-2H1-toluene, the ratio obtained for o-cresol was taken as 100% retention, because no loss of 2H would result from oxidation at that position. The tabulation of ions for each peak was an average taken over the entire peak.

Calculation of Isotope Effects.

Relevant methods to calculate isotope effects have been published (6–8, 14). Briefly, the 2H isotope effect on the oxidation of ring-deuterated p-xylene was determined by dividing the ratio of protio products (ring-hydroxylated/methyl-hydroxylated) by the same ratio of deutero products. Because perdeuterated p-xylene was used to determine the isotope effect on methyl oxidation, a correction to account for the inverse isotope effect from ring deuteration was obtained from multiplying the ratio of deutero products (ring-hydroxylated/methyl-hydroxylated) to protio products (ring-hydroxylated/methyl-hydroxylated) by the inverse isotope effect determined for ring deuteration. The isotope effects for hydroxylation of 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene were calculated as the ratio of the percentage of the given product obtained from protio toluene to the percentage of the same product obtained from deutero toluene.

Results

Paradigm for Analysis of Deuterium Isotope Effects.

For examination of the 2H isotope effects expected from the different pathways of Fig. 1, three principles are (i) C—D bond breakage will give a normal isotope effect, (ii) a change in hybridization of a C—D bond from sp2 to sp3 will give an inverse isotope effect, and (iii) the percentage of deuterium retention depends on the different pathways. By consideration of these principles, plausible interpretations of 2H isotope effects and deuterium-retention patterns have been made (6–8). For pathway A of Fig. 1, direct insertion into a C—D bond, a normal isotope effect is expected along with complete deuterium loss. For pathways B and C of Fig. 1, the observed isotope effects depend on the partitioning between various pathways available for the formation of the final phenolic product. For pathway B, an inverse isotope effect for oxidation at the position of deuteration is expected because of the change from sp2 to sp3 hybridization. Direct conversion between the cationic intermediate and the phenol will result in complete loss of the deuterium. Alternatively, rearrangement of the cationic intermediate to a ketone intermediate is associated with an NIH shift (15). Subsequent isotopic fractionation during rearomatization of the ketone intermediate will be governed by a normal isotope effect of ≈4–5, resulting in a maximal deuterium-retention value of ≈75–80%.

For reactions involving an epoxide intermediate (Fig. 1C), irreversible opening of the epoxide ring will result in an inverse isotope effect for hydroxylation at the position of deuteration due to a change in hybridization from sp2 to sp3 and normal secondary isotope effects for deuteration adjacent to the position of hydroxylation. In contrast, reversible opening of the epoxide ring will result in a normal secondary isotope effect on hydroxylation at the position of deuteration (6, 8, 16). Other permutations can be found in the pioneering studies on these reactions (6–8).

Investigations of P450 and aromatic amino acid hydroxylase within the framework of this paradigm suggest that addition/rearrangement (Fig. 1B) is the reaction pathway most frequently consistent with the available experimental data (6, 8, 16). However, a single enzyme may use multiple, competing pathways, and partitioning between the available pathways is substrate-dependent. Moreover, specific examples consistent with epoxide intermediate formation (Fig. 1C) have also been identified (17–19). T4moH provides an opportunity for further investigation of these mechanistic alternatives precisely because this diiron active site is uniquely evolved for toluene binding and aromatic hydroxylation.

Intramolecular Isotope Effects with p-Xylene.

This is a useful substrate for hydroxylation studies, because only two products are possible, and these arise from potentially distinct aromatic and methyl C—H hydroxylation reactions. Table 1 shows the product distributions obtained from the oxidation of p-xylene, ring-deuterated p-xylene, and perdeuterated p-xylene, along with the calculated intramolecular isotope effects. Deuteration of the aromatic ring results in a substantial inverse isotope effect of 0.735, which indicates a change in hybridization from sp2 to sp3 at the carbon atom bearing the deuteron. This result is consistent with either addition/rearrangement (Fig. 1B) or epoxidation mechanisms (Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

Product distributions (percentages of ring- and methyl-hydroxylated products) and isotope effects observed during the oxidation of deuterated p-xylene

| p-Xylene | Position of oxidation

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring* | Methyl | Ratio† | IIE‡ | |

| 2H0– | 19.6 (0.7) | 80.4 (0.7) | 0.244 (0.009) | |

| 2H4– | 24.9 (1.5) | 75.1 (1.5) | 0.332 (0.063) | 0.735 (0.193) |

| 2H10– | 42.4 (0.4) | 57.6 (0.4) | 0.736 (0.012) | 2.22 (0.04) |

Includes 2,5- and 2,4-dimethyl phenol.

Ring to methyl-hydroxylated products.

Intramolecular isotope effects (IIE) calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Replacement of both ring and methyl protons with deuterium gave an apparent normal isotope effect of 3.02 for methyl hydroxylation. However, this value contains the contribution of the inverse isotope effect resulting from ring deuteration. After accounting for the effect of ring deuteration (3.02 × 0.735), the isotope effect on oxidation of the methyl group was 2.22. This normal isotope effect is typical for the oxidation of an sp3- hybridized carbon when a rate-limiting step is the cleavage of the C—H bond. Interestingly, similar reactions catalyzed by P450 gave normal isotope effects of 7.53 and 9.61 for methyl hydroxylation of o- and p-xylene, respectively (20). Because the active-site dynamics of the substrate can influence the magnitude of isotope effects (20), it is plausible that the intrinsic isotope effect for reaction of T4moH with the methyl position may be partially masked due to limited substrate movement within the active site. This assessment is consistent with the high regiospecificity observed with T4moH (5).

Intramolecular Isotope Effects with Deuterated Toluenes.

Previous studies have shown that natural T4moH and the G103L isoform have similar kcat/KM values and coupling efficiencies (5) but distinct product distributions during the oxidation of toluene. Thus T4moH produces ≈96% p-cresol, whereas the G103L isoform gives 55% o-cresol, 25% p-cresol, and 20% m-cresol. These differences in product distributions, specifically the increased amounts of m- and o-cresol given by the G103L isoform, have been of advantage in assessing the significance of the isotope effects measured in these studies. Table 2 shows the intramolecular isotope effects observed for the oxidation of 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene by these two isoforms. The product distributions used to calculate the intramolecular isotope effects were determined by parallel analyses of untreated and MSTFA-treated products with two different GC columns to ensure proper and consistent integration of all the product peaks.

Table 2.

Intramolecular isotope effects during oxidation of 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene

| Toluene | Isoform | Intramolecular isotope effect*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ortho- | para- | meta- | ||

| 4-2H1- | T4moH | 0.990 (0.032) | 0.994 (0.001) | 1.060 (0.024) |

| G103L | 0.997 (0.002) | 0.935 (0.045) | 1.015 (0.002) | |

| 3,5-2H2- | T4moH | 1.000 (0.000) | 0.999 (0.006) | 0.950 (0.000) |

| G103L | 0.993 (0.010) | 1.002 (0.016) | 0.966 (0.000) | |

The isotope-effect values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods from the average of 9–13 independent measurements with standard error reported in parentheses.

The two isoforms displayed similar isotope-effect patterns with both substrates, suggesting that chemical aspects of the reaction mechanism were unchanged even as the introduced mutation significantly changed the product distribution. For para-hydroxylation with 4-2H1-toluene, T4moH yielded a small, statistically significant inverse isotope effect of 0.994, whereas the G103L isoform showed a more substantial inverse isotope effect of 0.935. Similarly, inverse isotope effects of 0.950 and 0.966 were observed during the meta-hydroxylation of 3,5-2H2-toluene by T4moH and the G103L isoform, respectively. For meta-hydroxylation of 4-2H1-toluene, a normal secondary isotope effect was observed from both isoforms. In contrast, for para-hydroxylation of 3,5-2H2-toluene, the observed isotope effect was unity. In this latter case, the normal secondary isotope effect anticipated for hydroxylation at the para position may be masked by the enzyme regiospecificity and the para-directing nature of the toluene functional group. Evaluation of results with the G103L isoform, where o-cresol represents ≈55% of total products, showed no statistically significant isotope effect for hydroxylation at the ortho position. Within experimental error (Table 2), a similar conclusion was made for the reaction of T4moH.

Deuterium Retention.

Table 3 shows the amount of deuterium retained in the products obtained from T4MO-catalyzed oxidation of deuterated toluenes. Again, both T4moH and the G103L isoforms showed similar patterns of deuterium retention. When 4-2H1-toluene was the substrate, ≈75% of the deuterium was retained during formation of p-cresol, whereas essentially all deuterium was retained during formation of o-cresol. This latter result would be expected for an oxidation remote from the isotopic label. Surprisingly, almost complete retention of deuterium was also observed in m-cresol obtained from 4-2H1-toluene, suggesting that this product also arose from an oxidation remote from the isotopic label. When 3,5-2H2-toluene was the substrate, the amount of deuterium retained in p-cresol was approximately constant for both isoforms at ≈72%. Moreover, the amount of deuterium retained in o-cresol varied from 66% to 72%, whereas 54–60% of the deuterium was retained in m-cresol. These results with 3,5-2H2-toluene indicate proximity of the meta position to oxidative intermediates leading to all possible phenolic products.

Table 3.

Deuterium retention after oxidation of 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene by T4MO

| Toluene | Isoform | Deuterium retained in cresol products*, %

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| o-cresol | p-cresol | m-cresol | ||

| 4-2H1 | WT | 100 | 74.9 (0.2) | 97.8 (0.2) |

| G103L | 100 | 78.0 (0.4) | 93.4 (0.3) | |

| 3,5-2H2 | WT | 71.8 (0.4) | 70.8 (0.1) | 60.3 (0.2) |

| G103L | 66.3 (0.1) | 73.3 (0.1) | 53.7 (0.1) | |

Percentages are the average of 9–13 measurements with the standard error reported in parentheses.

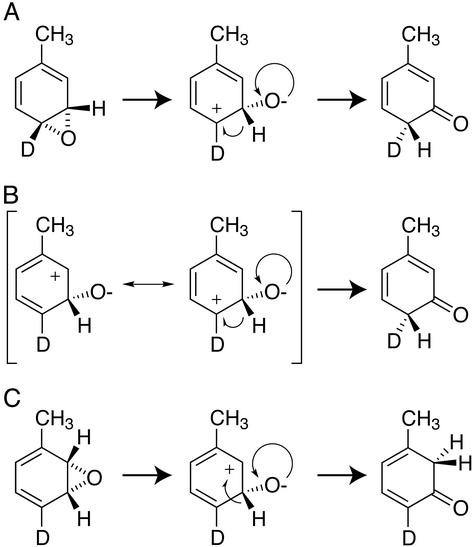

Fig. 2 shows possible mechanisms for the reaction of 4-2H1-toluene leading to a ketone precursor of m-cresol that also account for the observed deuterium retention. In Fig. 2A, a 3,4-epoxide must rearrange to a C-3 ketone with requisite migration of a C-3 proton to C-4 to yield m-cresol. This rearrangement gives rise to sp3 hybridization at C-4 with both a deuteron and proton present. Alternatively, Fig. 2B shows that direct addition of electrophilic oxygen to C-3 leads to a carbocation that can be resonance-stabilized at either the C-2 or C-4 positions. Although exclusive migration of the meta-proton to the C-2 cationic position (Fig. 2B Left) would lead to near-complete retention of deuterium at the para position, migration to the para position would be favored (Fig. 2B Center) because of an sp2-to-sp3 conversion at the C-4 position bearing a deuteron. Thus the rearrangements of Fig. 2 A and B predict the formation of a ketone intermediate with the same isotopic composition at C-4. Competition between the removal of a proton or deuteron during rearomatization would be governed by an intrinsic normal isotope effect of ≈4–5, corresponding to a maximum possible deuterium retention of ≈75–80%. However, because near-complete retention of deuterium was observed in m-cresol (93–98%, Table 3), the mechanisms of Fig. 2 A and B are not consistent with the experimental results.

Figure 2.

Rearrangement reactions of 4-2H1-toluene intermediates leading to m-cresol formation. The predicted positions of the deuteron in a C-3 ketone intermediate before rearomatization are indicated. (A) Rearrangement of a 3,4-epoxide. (B) Addition of electrophilic oxygen at the C-3 position. A proton shift to the C-4 position is favored because of the inverse isotope effect associated with sp2 to sp3 conversion at the site of deuteration. (C) Rearrangement of a 2,3-epoxide.

Alternatively, Fig. 2C shows that rearrangement of a 2,3-epoxide would lead to a C-3 ketone intermediate commensurate with a proton shift from C-3 to C-2. This meta-hydroxylation pathway would occur in isolation of C-4 deuteration, corresponding to the near-complete retention observed experimentally. Moreover, reaction of 3,5-2H2-toluene through a similar 2,3-epoxide intermediate would result in deuteron migration from C-3 to C-2 and partial isotopic retention in m-cresol, again matching the experimental results (Table 3).

Discussion

The studies reported here are directed toward understanding the mechanism of aromatic hydroxylation used by natural T4moH and a distinct active-site isoform G103L. One goal of our research is to define the stereochemical and mechanistic factors contributing to the high regiospecificity of this complex. Similar patterns of intramolecular isotope effects and deuterium retention determined for the T4moH and G103L isoforms indicate that both use the same chemical mechanism for toluene hydroxylation. Consequently, the altered product distributions observed with the G103L isoform must arise from different substrate-binding orientations relative to the active-site oxidant. Further examination of the isotope-effect results provides insights into the possible mechanism of action as elaborated below.

p-Xylene Hydroxylation Proceeds Through Two Mechanisms.

The differences in isotope effects observed for oxidation of either the ring or methyl positions indicate that T4MO utilizes different mechanisms to catalyze aromatic and aliphatic hydroxylations. Ring deuteration of p-xylene gives an inverse isotope effect consistent with rate-limiting conversion of the carbon bearing the deuteron from sp2 to sp3 hybridization. This finding corresponds to either an electrophilic addition to a single carbon atom (Fig. 1B) or formation of an epoxide intermediate during the reaction (Fig. 1C). In contrast, methyl deuteration of p-xylene results in a normal isotope effect for benzylic hydroxylation indicative of C—D bond cleavage during a rate-limiting step. Thus the nature of the substrate and the strength and character of the C—H bond influence the reactivity of T4moH, as has been observed for catalysis by cytochrome P450, pterin-dependent amino acid hydroxylases, and the related diiron enzyme methane monooxygenase (16, 21, 22).

Isotope-Effect and Deuterium-Retention Patterns.

Evaluation of the contributions of pathways B and C of Fig. 1 has been a hallmark application of intramolecular isotope-effect and deuterium-retention studies. The pathway of formation of a cationic intermediate and exclusive rearrangement to the ketone before rearomatization is consistent with the inverse isotope effects observed here for hydroxylation at the site of deuteration (Table 1). Moreover, the deuterium retention observed for para- hydroxylation of 4-2H1-toluene is consistent with the isotopic discrimination anticipated for rearomatization of a ketone intermediate containing a tetrahedral carbon bearing both a deuteron and a proton (Fig. 2 Right). However, by invoking pathway B for T4moH catalysis, unique binding orientations leading to the regiospecific insertion of oxygen into the C-4, C-3, and C-2 positions will be required, with substantial redistribution of these binding orientations provided by the G103L isoform. Because meta-hydroxylation of 4-2H1-toluene in both T4moH isoforms would only proceed by direct addition of electrophilic oxygen to the C-3 position (Fig. 2B), the high retention of deuterium observed would also require near-exclusive migration of the C-3 proton to the C-2 carbon as opposed to the favored migration to the C-4 carbon (Fig. 2B), resulting in the fractionation of isotopic content after rearomatization.

Alternatively, the present intramolecular isotope-effect studies suggest the involvement of an irreversibly opened epoxide intermediate in the T4MO-catalyzed hydroxylation of toluene. Thus both 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene give inverse isotope effects for hydroxylation at the position of deuteration, which indicates conversion from sp2 to sp3 hybridization during reaction at both the C-4 and C-3 positions. Furthermore, secondary isotope effects were observed for hydroxylation adjacent to the position of deuteration when 4-2H1-toluene was the substrate. These two results have been considered diagnostic for irreversible opening of an epoxide intermediate (6, 8, 16).

Further consideration of the deuterium-retention values observed for the m- and p-cresol products obtained from 4-2H1-toluene suggests that different epoxide isomers may be intermediates in the various hydroxylation reactions. For example, during the oxidation of 4-2H1-toluene, ≈75% of deuterium was retained in p-cresol, whereas ≈95% of deuterium was retained in m-cresol. Overall, the intramolecular isotope-effect and deuterium-retention results are consistent with the involvement of a 2,3-epoxide intermediate during m-cresol formation and a 3,4-epoxide during p-cresol formation.

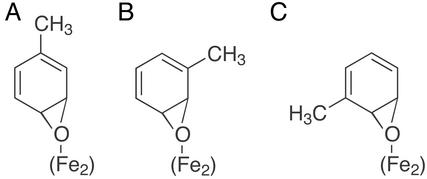

Role of an Epoxide Intermediate in T4moH Regiospecificity.

The almost exclusive para-hydroxylation observed for T4moH may be facilitated by an active site-directed opening of an epoxide intermediate. Because T4moH gives para-hydroxylation of toluene, anisole, chlorobenzene, and nitrobenzene (5), the observed regiospecificity cannot be accounted for by aromatic-ring substituent effects alone. Fig. 3A indicates that a 3,4-epoxide intermediate may be rendered asymmetric by interactions between the epoxide oxygen and the (Fe)2 center and that this interaction may also promote rearrangement toward the desired product p-cresol. Asymmetry of epoxidation transition states has been determined by computational methods (23). Moreover, a change in orientation of the bound substrate may play a prominent role in determining which epoxide isomer is formed and how interactions within the active site influence the rearrangements required to form the final product. Fig. 3 B and C show that formation of a 2,3-epoxide may arise from two different orientations of toluene within the active site, whereas subsequent (Fe)2-directed opening of the epoxide would give rise to either m-cresol (Fig. 3B) or o-cresol (Fig. 3C). Aromatic hydroxylation of p-xylene may also arise from orientations related to those indicated in Fig. 3 B and C, whereas the methyl-migration product 2,4-dimethylphenol may arise from a 1,2-epoxide and an orientation related to that of Fig. 3A. Metal–epoxide interactions have precedence in other contexts such as the use of Li- (24) and Cr-salen (25) complexes as catalysts for stereospecific epoxide opening. The interactions proposed in Fig. 3, coupled with the likely steric influence provided by a well defined substrate-binding site, offer an attractive and plausible explanation for the high regiospecificity observed from T4moH.

Figure 3.

Binding modes of epoxide intermediates relative to the (Fe)2 center and products derived from active site-directed opening of the epoxide ring.

Comparisons to Other Aromatic Hydroxylases.

The cumulative evidence for P450 and pterin-dependent amino acid hydroxylases (6, 8, 16–19), obtained in large part from intramolecular isotope-effect studies (Table 4), indicates that aromatic hydroxylation may occur through different pathways (epoxide, ketone, or direct phenol formation) depending on the enzyme isoform being studied, the substrate, and the presence or absence of deuterium at the site of oxidation (6, 13, 26). Most frequently, an addition/rearrangement mechanism similar to that shown in Fig. 1B has been concluded for aromatic hydroxylation by these enzymes. The isotope-effect and deuterium-retention patterns reported here suggest that T4MO instead may produce an epoxide intermediate on the predominant pathway for catalysis, in distinction to the mechanistic results for P450 and pterin-dependent amino acid hydroxylases.

Table 4.

Intramolecular isotope effects observed from various aromatic hydroxylases

| Enzyme | Substrate | 2H position | Hydroxylation

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| para- | meta- | |||

| T4moH | Toluene | para- | 0.994 (0.001) | 1.060 (0.024) |

| meta- | Unity | 0.950 (0.000) | ||

| T4moH | Toluene | para- | 0.935 (0.045) | 1.015 (0.002) |

| G103L | meta- | Unity | 0.966 (0.000) | |

| Tyrosine hydroxylase* | Tyrosine | para- | 1.22 (0.02) | Unity |

| meta- | Unity | 1.72 (0.28) | ||

| P450† | Chlorobenzene‡ | para- | 0.930 (0.020) | 1.090 (0.014) |

| meta- | Unity | 1.119 (0.016) | ||

| CYP2C9§ | Warfarin | para- | 0.96 (0.001) | Unity |

| meta- | 0.67 (0.001) | 1.17 (0.001) | ||

Isotope Effects on Benzylic Hydroxylation.

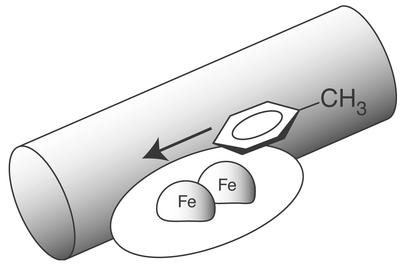

Although para- hydroxylation of mono-substituted benzenes provides the majority of products in most T4MO reactions, benzylic oxidation provides a minor contribution to the total product distribution obtained from toluene. Methyl hydroxylation could arise from free rotation of the substrate in the active site, a small subset of toluene bound in a different orientation, or movement of toluene through the active-site channel in a manner that leads to oxidation of the methyl group only after the opportunities for ring hydroxylation have been missed. During the oxidation of 4-2H1- and 3,5-2H2-toluene, the apparent isotope effects for benzylic hydroxylation (≈2 to ≈11) are in the range expected for direct cleavage of a methyl C—D bond even though no deuterium was present in the benzylic position of the substrates used for these measurements. Thus these apparent isotope effects for benzylic hydroxylation must arise from inverse isotope effects due to deuterium substitution on the aromatic ring. Fig. 4 provides a schematic representation of how substrate motions may contribute to this isotope-enhanced regiospecificity. By successive motion, a directed entry of toluene into the T4moH active site may first present the C-4 and C-3 positions to the (Fe)2 oxidant followed by the C-3 and C-2 positions and then the methyl group. Reaction at the aromatic ring thus would be favored by both the directional nature of substrate presentation to the (Fe)2 oxidant and an increased partitioning toward aromatic-ring hydroxylation caused by deuterium substitution and the associated inverse isotope effect. This consideration is supported by the observation that increasing the number of deuterons in the aromatic ring increased the apparent isotope effect for benzylic hydroxylation (≈2–3 for 4-2H1-toluene versus ≈5–11 for 3,5-2H2-toluene). In any case, the isotope effects calculated from the low percentage of benzyl alcohol produced by T4MO will be dramatically sensitive to small changes in percentages of the dominant ring-hydroxylation products.

Figure 4.

A model suggesting movement of toluene through the T4moH active site, which would first allow approach of the C-4 and C-3 positions followed by approach of the C-3 and C-2 positions and then the methyl group.

Mechanism of Toluene Hydroxylation.

The present results permit the construction of a reactivity model. For natural T4moH, toluene is proposed to enter the active site in an orientation that leads to a first opportunity for reaction at the C-4 and C-3 positions (Fig. 3A), whereas a minor secondary orientation (or further motion) can lead to reaction at the C-3 and C-2 positions (Fig. 3 B and C). In both binding orientations, an epoxide intermediate may be formed and irreversibly opened as directed by interactions within the active site. Thus a 3,4-epoxide would open nearly exclusively to give the naturally preferred product p-cresol in 96% yield, whereas a 2,3-epoxide yields ≈4% of the total products as m- and o-cresol in a 2:1 ratio. Because T4MO gives para-hydroxylation of nearly all monosubstituted benzenes tested (5), it is likely that each of these substrates experience the same orientational effects as toluene. Moreover, the directionality of epoxide-ring opening given by active-site interactions must be sufficiently dominating to overcome inductive or resonance substituent effects such as those typically expected for predominant hydroxylation of nitrobenzene to m-nitrophenol. For the G103L isoform, the isotope effects and deuterium-retention patterns also suggest that p-cresol may arise from a 3,4-epoxide (Fig. 3A), whereas m-cresol will arise from a 2,3-epoxide (Fig. 3B). Because the orientation shown in Fig. 3B would preferentially lead to m-cresol, the alternative binding mode proposed in Fig. 3C would be preferred in the G103L isoform after consideration of the participation of the (Fe)2 center. This orientation would correspond to the observed 55% yield of o-cresol and also account for the observed deuterium retention.

Our present understanding of T4moH catalysis is enhanced by the following additional studies. First, the x-ray structure of the methane monooxygenase hydroxylase (MmoH) indicates that a short access path from solvent to the diiron center may pass through a “Leu gate” (27). Second, directed-evolution studies of toluene 2-monooxygenase revealed that a V106A mutation in this “gate” region led to an increased reactivity with a larger substrate, naphthalene (28). Third, the position of G103L used in these studies is predicted to lie along this entry portal, in close proximity to the (Fe)2 center. Fourth, mutations in the methane monooxygenase catalytic effector MmoB that decreased residue size also increased the reactivity of MmoH with larger substrates (29). Fifth, interplay between the T4MO catalytic effector protein (T4moD) and active-site residues of various T4moH isoforms provides an essential part of the regiospecificity (5). One potential role for effector protein binding may be to induce a conformational change at this critical entry point (30). How the surface of T4moH and required interactions with the catalytic effector protein T4moD may govern the orientation and entry of substrate into the active site is a matter of obvious interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. W. W. Cleland for enlightening discussion. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Early Career Development Program Grant MCB-9733734 (to B.G.F.). K.H.M. was a trainee of National Institutes of Health Institutional Biotechnology Pre-Doctoral Training Grant T32 GM08349.

Abbreviations

- T4MO

toluene 4-monoxygenase

- T4moH

hydroxylase component of T4MO

- MSTFA

N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Fitzpatrick P F. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massey V. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22459–22462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox B G. In: Comprehensive Biological Catalyis. Sinnott M, editor. Vol. 3. San Diego: Academic; 1998. pp. 261–348. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guengerich F P. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:611–650. doi: 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell K H, Studts J M, Fox B G. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3176–3188. doi: 10.1021/bi012036p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korzekwa K R, Swinney D C, Trager W F. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9019–9027. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korzekwa K R, Trager W F, Gillette J R. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9012–9018. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darbyshire J F, Iyer K R, Grogan J, Korzekwa K R, Trager W F. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:1038–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whited G M, Gibson D T. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3010–3016. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3010-3016.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell K H. Ph.D. thesis. Madison: University of Wisconsin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pikus J D. Ph.D. thesis. Madison: University of Wisconsin; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavia D L, Lampman G M, Kriz G S. Introduction to Organic Laboratory Techniques. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanzlik R P, Hogberg K, Judson C M. Biochemistry. 1984;23:3048–3055. doi: 10.1021/bi00308a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones J P, Korzekwa K R, Rettie A E, Trager W F. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:7074–7078. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd D R, Daly J W, Jerina D M. Biochemistry. 1972;11:1961–1966. doi: 10.1021/bi00760a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzpatrick P F. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:1133–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boyd, D. R., Hamilton, J. T. G., Sharma, N. D., Harrison, J. S., McRoberts, W. C. & Harper, D. B. (2000) Chem. Commun., 1481–1482.

- 18.Born S L, Caudill D, Fliter K L, Purdon M P. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:483–487. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kisselev P, Schwarz D, Platt K-L, Schunck W-H, Roots I. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1799–1805. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanzlik R P, Ling K-H J. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:9363–9370. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaz A D N, McGinnity D F, Coon M J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3555–3560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valentine A M, Stahl S S, Lippard S J. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:3876–3887. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singleton D A, Merrigan S R, Liu J, Houk K N. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:3385–3386. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramirez A, Collum D B. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11114–11121. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobsen E N. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:421–431. doi: 10.1021/ar960061v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korzekwa K, Trager W, Gouterman M, Spangler D, Loew G H. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:4273–4279. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenzweig A C, Brandstetter H, Whittington D A, Nordlund P, Lippard S J, Frederick C A. Proteins. 1997;29:141–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canada K A, Iwashita S, Shim H, Wood T K. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:344–349. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.344-349.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallar B J, Lipscomb J D. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2220–2233. doi: 10.1021/bi002298b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallagher S C, Callaghan A J, Zhao J, Dalton H, Trewhella J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6752–6760. doi: 10.1021/bi982991n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]